Introduction

Arson and fire-setting are highly prevalent among mentally disordered populations, particularly those patients held in conditions of security (Long, Fitzgerald and Hollin, in press). The statistics from several European countries, including Finland (Repo, Virkkunen, Rawing and Linnoila, Reference Repo, Virkkunen, Rawing and Linnoila1997), Sweden (Fazel and Grann, Reference Fazel and Grann2002) and the UK (Coid, Kahtan, Gault and Jarman, Reference Coid, Kahtan, Gault and Jarman2000), indicate that about one in ten of those admitted to a forensic psychiatric service has a history of fire-setting. The term firesetter (an individual who deliberately sets fires) refers to a broader group of individuals than those convicted of a crime of arson (Dickens and Sugarman, Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Dickens, Sugarman and Gannon2012). Fire-setting is the term used throughout this article except where the term arson is accurate in the context of the quoted research. A survey of psychiatrists about the dangers posed by firesetters revealed significant professional concern about such patients (Sugarman and Dickens, Reference Sugarman and Dickens2009).

There is a range of mental disorders, sometimes comorbid, frequently associated with arson, although pyromania, a psychiatric disorder specifically concerned with pathological fire-setting, is rare (Lindberg, Holi, Tani and Virkkunen, Reference Lindberg, Holi, Tani and Virkkunen2005). Rice and Harris (Reference Rice and Harris1991) reviewed the clinical files of 243 male firesetters (of whom only one met the diagnostic criteria for pyromania) admitted to a Canadian maximum security psychiatric facility. The most common diagnoses were personality disorder, which was evident in over one-half of the sample, and schizophrenia, prevalent in about one-third of the sample. Enayati, Grann, Lubbe and Fazel (Reference Enayati, Grann, Lubbe and Fazel2008) reviewed the diagnoses of 214 arsonists (59 women and 155 men) referred for inpatient psychiatric assessment. They reported that the most frequently observed diagnoses for both males and females were for substance use disorders, personality disorders, and psychoses (typically schizophrenia). Alcohol use disorders were more prevalent in the female arsonists. Labree, Nijman, van Marle and Rassin (Reference Labree, Nijman, van Marle and Rassin2010) reported that, when compared to similar patients, arsonists were more likely to have received psychiatric treatment prior to their offence and to have a history of severe alcohol abuse. The arsonists were less likely to have a major psychotic disorder, although delusional thinking was judged to play a causal role in the fire-setting in just over one-half of the cases. In a sample of female arsonists drawn from the prison population, Noblett and Nelson (Reference Noblett and Nelson2001) also noted high levels of childhood sexual abuse and deliberate self-harm.

Schizophrenia is often associated with arson (Ritchie and Huff, Reference Ritchie and Huff1999), particularly so with female samples (Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Ahmad, Edgar, Hofberg and Tewari2007). Anwar, Långström, Grann and Fazel (Reference Anwar, Långström, Grann and Fazel2011) surveyed the incidence of schizophrenia among 1340 men and 349 women convicted for arson. They found that compared to a control group from the general population, those diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychoses were at a significantly increased risk of being convicted for arson. Indeed, Anwar et al. noted that the likelihood of being diagnosed with schizophrenia was 20 times greater for the arsonists than for the controls and that there was a higher rate of schizophrenia among the female arsonists.

Dickens et al. (Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Ahmad, Edgar, Hofberg and Tewari2008) investigated the relationship between low IQ and arson in 202 men and women referred for psychiatric assessment. They found that 88 of the sample had an IQ of 85 or below: these low IQ arsonists set more fires than those of a higher IQ although they did not differ in the range or extent of their previous criminal convictions. A survey of the case records of 90 women admitted to a secure psychiatric facility (Long et al., in press) found that 49 had a history of fire-setting (including convictions for arson). In comparison with other women admitted to security, these 49 women had more previous convictions, were more impulsive, and were more likely to be diagnosed with either personality disorder or schizophrenia. The high proportion of multiple firesetters in the Long et al. (in press) study is in keeping with previous studies that indicate that fire-setting is both a complex phenomenon and a continuing challenge for psychiatric services (Coid, Kahtan, Gault and Jarman, Reference Coid, Kahtan, Gault and Jarman1999; Miller and Fritzon, Reference Miller and Fritzon2007).

Rice and Harris (Reference Rice and Harris1996) reported a post-discharge 8-year follow-up of the 243 male firesetters in their 1991 study. The rate of recidivism for fire-setting was low, estimated at a 16% chance of further arson. The strongest predictors of repeat fire-setting were the intensity of the individual's fire-setting history, a younger age, lower intelligence, and no history of violent behaviour. Dickens et al. (Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Edgar, Hofberg, Tewari and Ahmed2009) looked at predictors of recidivism in 167 male and female adult arsonists referred to psychiatric services in England. They found that just under one-half of the sample had set more than one fire and that diagnoses of personality disorder and learning disability were more frequent among the multiple firesetters compared to those who set only a single fire.

In addition to the association between arson, psychiatric co-morbidity and the developmental and behavioural correlates described above, a range of psychological vulnerability factors needs to be examined when considering assessment and treatment interventions (Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley, Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011). These include interpersonal characteristics such as limited social skills, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, and problems of adjustment in education and employment (e.g. Puri, Baxter and Cordess, Reference Puri, Baxter and Cordess1995; Doley, Reference Doley2009). Anger arousal (sometimes linked to a revenge motive; Ritchie and Bluff, Reference Ritchie and Huff1999) has been identified as a precursor to fire-setting (Stewart, Reference Stewart1993) while Coid et al.'s (Reference Coid, Kahtan, Gault and Jarman1999) study of self-mutilating prisoners describes a list of emotions (e.g. symptom relief, excitement, sexual arousal) associated with fire-setting that may maintain or promote the behaviour. Others have commented on the association between pathological fire-setting and both exposure to fire at an early age (Perrin-Wallquist and Norlander, Reference Perrin-Wallquist and Norlander2003) and feelings of excitement and fascination with fire and the trappings of fire (Doley and Fineman, Reference Doley, Fineman, Dickens, Sugarman and Gannon2012). Of equal importance are cognitive distortions, offence-supportive schemas or implicit theories (e.g. fire is controllable; the normalization of violence) that are supportive of fire-setting behaviours (O’Ciardha and Gannon, Reference O’Ciardha and Gannon2012).

Despite the increasing research attention being paid to fire-setting, there is little understanding of the treatment needs of firesetters (Gannon and Pina, Reference Gannon and Pina2010). Multi-factor theories of adult fire-setting include Dynamic Behaviour Theory (Fineman, Reference Fineman1980, Reference Fineman1995), Functional Analysis Theory (Jackson, Glass and Hope, Reference Jackson, Glass and Hope1987) and the Multi Trajectory Theory of Adult Fire-setting (M-TTAF; Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011).

Jackson et al.'s (Reference Jackson, Glass and Hope1987) Functional Analysis perspective maintains that fire-setting is used to resolve problems that are viewed by the individual to be impossible to solve by other means. The functional analysis incorporates antecedent, behavioural and consequential (ABC) variables hypothesized to be associated with serial fire-setting. In terms of antecedents, five main factors underlie intentional fire-setting: (1) psychosocial disadvantage; (2) life dissatisfaction and self-loathing; (3) social ineffectiveness; (4) factors that determine that individual experience of fire-setting; and (5) fire-setting triggers (internal or external). Reinforcement contingencies (including negative reinforcement) play a key part in promoting and maintaining fire-setting behaviour. The model has been reviewed by Gannon et al. (Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011) who note that it does not explain why fires are set by those without social disadvantages or why some who have experienced social disadvantage do not set fires. Gannon et al. (Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011) also note the implicit assumption that all repetitive fire-setting is accompanied by fire interest, and particularly that the model does not focus (unlike the Dynamic Behaviour Theory; Fineman, Reference Fineman1980, Reference Fineman1995) on cognitions that may prompt or reinforce fire-setting. The Multi-Trajectory Theory of Adult Fire-setting (Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011) represents the most comprehensive attempt to explain fire-setting to date by reference to five pro-typical trajectories, although the theory as a whole has yet to be empirically tested. The Functional Analysis Theory has, however, been widely employed by clinicians as a way of conceptualizing fire-setting behaviour because of its clear multi-factor framework and its evidence base (Doley and Watt, Reference Doley, Watt, Dickens, Sugarman and Gannon2012), because of its applicability to patients with intellectual disability (Taylor, Thorne and Slavkin, Reference Taylor, Thorne, Slavkin, Lindsay, Taylor and Sturmey2004) and because of its value in guiding treatment interventions (Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011).

Given the association between mental disorder and arson it may be expected that specialized treatment programmes would be available, as is the case for other problematic behaviours such as violence (Braham, Jones and Hollin, Reference Braham, Jones and Hollin2008). However, Palmer, Caulfield and Hollin's (Reference Palmer, Caulfield and Hollin2007) national survey of service provision for arsonists in England and Wales found that within mental health units there was evidence of a small number of interventions for learning disabled forensic populations (Day, Reference Day1988). These interventions, typically provided on an individual basis, generally used a combination of cognitive-behavioural methods and education. There was no evidence of a systematic approach to intervention and there were no large-scale evaluations of the effectiveness of interventions. The same finding was evident within the criminal justice system despite the availability of effective interventions for other types of offender such as violent (Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Palmer, McGuire, Hounsome, Bilby and Hollin2008) and sex offenders (Mann and Fernandez, Reference Mann, Fernandez, Hollin and Palmer2006). Horley and Bowlby (Reference Horley and Bowlby2011) make the point that at present there is a marked absence of an evidence-based treatment for arsonists and firesetters. They also note that if effective treatments are to be developed then they must take into account both criminogenic and pathological factors at the individual level.

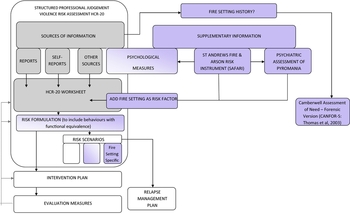

The concern here is with the development of an assessment for use with arsonists and firesetters that would, as Horley and Bowlby (Reference Horley and Bowlby2011) recommend, take into account individual criminogenic factors and personal pathology and provide a treatment direction. Despite the establishment of gender differences between firesetters, there is currently no compelling reason to devise radically different approaches to assessment and treatment (Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Ahmad, Edgar, Hofberg and Tewari2007). The current project took place within the larger context of the development of services for women accessing secure psychiatric services. The larger project had a two-stage strategy: (1) to establish a best practice model of care for secure settings, including individual and group treatment based on a patient needs assessment; (2) The development of a suite of assessments to guide the selection of a patient for a range of population-specific treatment modules. The first stage of this project is complete and now operating within St Andrews Hospital (Long, Fulton and Hollin, Reference Long, Fulton and Hollin2008; Long, Collins, Mason, Sugarman and Hollin, Reference Long, Collins, Mason, Sugarman and Hollin2011); the next step is to address a gap in the literature by developing an assessment specifically for fire-setting. In practice this assessment would augment the structured assessment of risk and need (HCR 20; Webster, Douglas, Eaves and Mark, Reference Webster, Douglas, Eaves and Mark1997) which is already in use (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fire Setting Protocol – Process Model

Method

Context

The study was carried out in the Women's Service of St Andrew's Healthcare, Northampton, UK. The majority of admissions to the service are women detained under the Mental Health Act who typically present with challenging behaviour alongside a forensic history and a history of substance use and abuse (Long et al., Reference Long, Fulton and Hollin2008). The patients are admitted to either a mental health or learning disability treatment pathway. In addition to learning disability, most patients of this type have a primary diagnosis of personality disorder (mostly emotionally unstable type) and to a lesser extent schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Approach to assessment

In keeping with the cognitive-behavioural underpinnings of the overall treatment programme, Jackson et al.'s (Reference Jackson, Glass and Hope1987) functional analysis was selected as the conceptual basis for the fire-setting assessment. Data used to inform a functional analysis (a hypothetical working model of the problem behaviour) include: (1) information on the situations in which fire-setting occurs; (2) which responses (emotional, physiological, cognitive, overt) behaviours occur; and (3) the consequences of fire-setting that might reinforce future fire-setting.

In order to define key antecedents and consequences for fire-setting the functional analysis was based on the most significant fire, typically the most recent or the fire linked to the index offence, set by the patient. A secondary purpose was to gather information on treatment readiness, fire-setting related insight, self-efficacy and risk to be used in conjunction with the results of an adequate functional analysis for treatment planning. The purpose of the assessment was to generate an understanding of the factors that were contributing to the fire-setting behaviour which might inform case formulation and treatment (Sturmey and McMurran, Reference Sturmey, McMurran, Sturmey and McMurran2011).

The development of the St Andrew's Fire and Arson Risk Inventory (SAFARI) was undertaken by an experienced clinical team of four senior clinicians (two consultant psychologists, a senior CBT therapist, and a clinical development facilitator) along with an academic consultant. There were five stages in the development of SAFARI.

Stage 1

The extant literature was used to inform the framing of the interview questions relating to the antecedents, behaviour, and consequences (A:B:C) necessary to formulate a functional analysis. Accordingly, the semi-structured interview included open ended and closed questions covering background (developmental) behaviour, cognitive (emotional, e.g. anger and negative affect), environmental factors, and specific trigger events (Bumpass, Fagelman and Brix, Reference Bumpass, Fagelman and Brix1983).

For each fire, questions covered background (age at time of fire, who living with, whether in education or employment); plans prior to fire-setting (time spent thinking about the fire and special preparations); concerns about being caught (prior thought), steps to avoid detections; wanting to be caught; plan and intention (to damage property, harm self or others); emotional state prior to fire-setting (including cognition); setting the fire (what set fire to; use of accelerants; prior preparation); thoughts and feelings when fire-setting; others at fire scene/others who knew about fire beforehand; thoughts and feelings after setting the fire; police/fire brigade presence and associated feelings; whether an action other than fire-setting was considered; and current thoughts and feelings about the fire-setting. It therefore incorporates enquiry central to Jackson et al.'s (Reference Jackson, Glass and Hope1987) model but also focuses on the thought (cognitive) process surrounding the fire-setting (Gannon et al., Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011) from which factors such as cognitive distortions or offence supportive schemas can be inferred. Emphasis is placed on the 24-hour period before the fire-setting event.

A summary checklist of antecedents, informed by the problems section of the Comprehensive Drinkers Profile (Miller and Martlatt, Reference Miller and Marlatt1987), for each fire was compiled. Patients were asked to describe from a list of problems (e.g. mental illness; health problems; substance problems; family conflict) those applicable in the lead up to fire-setting (along with help received, treatment compliance and self-help attempts) and, in a secondary analysis, those that were directly related to fire-setting. Assessment information was then summarized in terms of a preliminary functional analysis. Several versions of the interview were then piloted with therapy staff who were asked to rate ease of administration (1 = easy to 3 = difficult), acceptability to client (1 = acceptable, 2 = not acceptable), and length (1 = too short, 2 = about right, 3 = too long).

Stage 2

Questions regarding Readiness to Change were adapted from the Corrections Victoria Treatment Readiness Questionnaire (Casey, Day, Howells and Ward, Reference Casey, Day, Howells and Ward2007) specifically for fire-setting. Similarly, questions related to fire-setting self-efficacy were based on items drawn from the Situational Confidence Questionnaire (SCQ-8; Breslin, Sobell, Sobell and Agrawal, Reference Breslin, Sobell, Sobell and Agrawal2000) and the Drug Taking Confidence Questionnaire (DTCQ; Sklar and Turner, Reference Sklar and Turner1999), with additional items added as informed by the fire-setting literature. The final section gathered details about a range of factors: these included (i) early exposure to fire, (ii) circumstances under which patients might want to set a fire, (iii) the probability of future fire-setting, (iv) ability to resist the urge to set fires, (v) help required, (vi) barriers to change, and (vii) the patient's understanding of their fire-setting behaviour.

The assessment concludes with a summary of the analysis, indications for assessment and treatment, and a treatment action plan. The criteria for the final inclusion of questions were: (a) those agreed by a consensus of the authors of SAFARI as fire-setting research related and relevant to a functional analysis of fire-setting; (b) those rated by therapy staff as easy to administer and acceptable to the client. The Inventory was piloted using the random probe technique (Schuman, Reference Schuman1966) and assessed for comprehensibility (Flesch, Reference Flesch1948) by a population with mild learning disability.

Stage 3

Test-retest reliability was assessed by one of the same staff members re rating after a 4-week interval six previously evaluated interviews. Inter-rater reliability was also assessed. Finally, interval consistency (the consistency of results across SAFARI items) was assessed by having the outcomes from each completed assessment reviewed by four qualified clinical psychologists and comparing them to those of the authors of the assessment.

Stage 4

To assess content validity a panel (Nunally and Bernstein, Reference Nunally and Bernstein1994) of six consultant psychologists who worked in secure forensic settings were asked to rate SAFARI questions according to: (a) their relevance to the assessment of fire-setting behaviour (1 = not relevant to 6 very relevant); (b) the extent to which they were likely to produce sufficient information for a functional analysis of fire-setting incidents (1 = insufficient information to 6 = sufficient). Convergent validity was assessed by correlating SAFARI “Reasons for fire-setting” with fire risk indicators and early warning signs of the organization's Risk Management Summary.

Ethics

This study was part of a wider scale service evaluation project given ethical approval by the local NHS Research Ethics Committee (LNRI – 06/22501/91).

Participants

Fifteen women with a history of fire-setting and detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 took part in this study. Their mean age was 26.43 years (SD = 14.08; range 19–45 years) and the majority were of Caucasian origin (n = 13), single (n = 14), and had a forensic history (73%). The majority of these women (n = 9) had a diagnosis of personality disorder emotionally unstable type, some (n = 3) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, and others (n = 3) a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder or depression.

Results

Feasibility

Staff rated SAFARI as acceptable to patients and easy to administer. However, it was seen as lengthy for a single administration and was generally being completed over two interviews. Completion of SAFARI took between 1 and 2 hours depending on the complexity of the patient's fire-setting history, their willingness to disclose detail, and their level of insight.

Comprehensibility

The Flesch Reading Ease (RE) formula (Flesch, Reference Flesch1948) was used to measure the comprehensibility of the SAFARI assessment tool. Scores vary from 0–100. The RE score was 94.6, indicating that the questions are easy to understand and so are comprehensible by over 95% of adults (Ley and Lewelyn, Reference Ley, Llewelyn, Broome and Llewelyn1995). SAFARI was therefore seen to be comprehensible by patients within the “mild” range of learning disability.

Reliability

Inter class correlation co-efficients were calculated: these provide an assessment of inter-rater reliability by comparing the amount of variance between individual raters with the overall variance. It is a measure of reliability equivalent to weighted Kappa (Fleiss and Cohen, Reference Fleiss and Cohen1973). Landis and Koch (Reference Landis and Koch1977) suggest that the degree of reliability is indicated by the following: 0.21-0.40 fair, 0.41-0.60 moderate, 0.61-0.80 substantial, and 0.81-1.00 perfect. Test- retest reliability was assessed for three sections of SAFARI that comprise the conclusions of the interview: reasons for fire-setting; treatment interventions (that map on to identified reasons); and treatment plan (specified groups and individual interventions including medication review). Intra class correlations were 0.78, 0.86 and 0.81 for the three sections respectively.

Inter-rater reliability ratings achieved a Kappa measure of agreement of 0.88. The assessment of internal consistency for the sample gave a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 with item total correlations ranging from 0.59 to 0.83.

Validity

For content validity all six panel respondents gave a positive rating score of 4 or more for the relevance of the SAFARI questions to the assessment of fire-setting and for its ability to produce sufficient information for a functional analysis. The overall mean score was 5.5 (mode = 6) for relevance and information 5.2 (mode = 5) for functional analysis. In terms of convergent validity there was a high level of agreement (Cronbach's a = 0.76) between reasons for fire-setting items (SAFARI) and fire risk indicators and early warning signs (Risk Management Summary).

Discussion

The development of a fire-setting assessment tool, SAFARI, was driven by a marked absence of valid and reliable instruments for this specific issue with mentally disordered populations. Gannon et al. (Reference Gannon, O’Ciardha, Doley and Alley2011) suggest that from a scientist-practitioner perspective clinical assessment and treatment should be guided by a theoretical and empirically based understanding of fire-setting. In this regard the advantages of the functional analysis (Jackson, Reference Jackson, McMurran and Hodge1994; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Glass and Hope1987) are that the core assumptions of this approach are supported empirically and are theoretically robust (Sturmey, Reference Sturmey2008). The use of functional analysis as a base for the development of SAFARI provides clinicians with a clear explanation of fire-setting in terms of an, at times complex, interplay of antecedents and consequences. In addition, it importantly provides a clear direction for clinical interventions that may lead to a flexible combination of treatment interventions. This combination may well include the elements of offence analysis along with the relationship between developmental history and adult coping styles that include coping skills, anger management, social problem solving, interpersonal interaction styles and assertiveness (Gannon, Reference Gannon2010). In this regard the format suggested by Linehan (Reference Linehan1993), which uses group treatment for skills training and individual treatment for managing fire-setting, might be most useful for those with a mental disorder that has contributed in some way to fire-setting (Fritzon, Reference Fritzon, Dickens, Sugarman and Gannon2012).

The reliability and validity of SAFARI within secure clinical settings for women were satisfactory. The information it provides when combined with assessment of fire-setting, self-efficacy and readiness for treatment can be used to produce an individualized treatment programme drawing on a range of group and individual treatments. SAFARI can also be used as a supplement to the HCR-20, enabling a wider formulation of risk that extends to behaviours with functional equivalence (e.g. Miller and Fritzon, Reference Miller and Fritzon2007).

The limited number of publications reporting group fire-setting interventions describe an amalgam of therapies and coping skills that are standard for patients in secure settings, differing only in terms of providing education regarding the dangers of fire-setting (Long et al., in press). An aim in the development of SAFARI was to facilitate the design of an individually-tailored treatment programme to address fire-setting, using a wide range of techniques to address identified targets for change. While SAFARI has many of the characteristics of a feasible assessment tool (Slade, Thornicroft and Glover, Reference Slade, Thornicroft and Glover1999), it also has limitations. The use of instruments such as SAFARI in secure forensic settings is potentially affected by a tendency for patients to deny or minimize past offending and by a reluctance to engage for fear of prolonging time in secure stay (Wheatley, Reference Wheatley1998), and the unreliability of self-report. However, these tendencies are offset by the finding that diary assisted timeline feedback (Rotgers, Reference Rotgers2002) is accurate over lengthy trial periods and by past records that prelude exclusive reliance on self-report. The assessment can be time consuming given that a lengthy interview is required and the requirement to analyse a sample of fires can lead to the collection of some redundant information, with attendant frustration in some patients. It is also clear that having a standardized assessment instrument for fire-setting only goes part of the way to arriving at complete understanding of the static and dynamic factors in individual cases (Horley and Bowlby, Reference Horley and Bowlby2011).

It is recommended that SAFARI will be of greatest benefit if implemented using a bespoke training programme as this is likely to increase staff motivation for its use and improve the reliability of information gathered. Further studies with SAFARI are required to verify its validity and reliability across a wider range of settings and with male patient populations. It is anticipated that the process of conducting a thorough assessment will not only guide treatments in sympathy with a cognitive-behavioural approach (e.g. Swaffer, Haggett and Oxley, Reference Swaffer, Haggett and Oxley2001) but will also facilitate the evaluation of fire-setting treatment with mentally disordered populations that to date are all too rare (Gannon and Pina, Reference Gannon and Pina2010; Long et al., in press).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Craig MacDonald for his contribution in the early stages of the development of SAFARI, and to Olga Dolley for her assistance with data collection and analysis.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.