Introduction

Evidence-based treatments (EBTs) are typically developed and evaluated in research settings where treatment integrity is high, in order to draw valid conclusions about treatment efficacy. Research conducted in community-based settings differs in several important ways, which may impact both treatment integrity and treatment quality when compared with research conducted in carefully controlled university settings (Villabø et al., Reference Villabø, Compton, Narayanan, Kendall and Neumer2018). Understanding how treatment integrity is related to treatment outcome and how well treatment integrity is maintained when transferring EBTs from university settings to community settings, could help improve the quality of care (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Jensen-Doss, Hogue, Kendall and Weisz2019). In order to do so, we need measures of treatment integrity that are reliable and valid, and which can be applied across a variety of research settings.

Treatment integrity is a multi-faceted term and can be measured in multiple ways. Two particularly important aspects of treatment integrity are therapist adherence and competence. Adherence refers to the extent to which a therapist delivers the treatment as intended (Southam-Gerow et al., Reference Southam-Gerow., McLeod, Arnold, Rodríguez, Cox, Reise, Bonifay, Weisz and Kendall2016) and avoids including elements that are not prescribed by the treatment protocol (Perepletchikova et al., Reference Perepletchikova, Treat and Kazdin2007; Southam-Gerow and McLeod, Reference Southam-Gerow and McLeod2013). For example, when implementing a CBT protocol for the treatment of paediatric anxiety, did the therapist structure the session with a clear agenda and review of homework assignments? Did the therapist include appropriate exposure exercises? Therapist competence, on the other hand, refers to the degree to which a therapist possesses the knowledge and skill required to deliver treatment procedures to the standards required to achieve its expected outcomes (Perepletchikova and Kazdin, Reference Perepletchikova and Kazdin2005, Perepletchikova et al., Reference Perepletchikova, Treat and Kazdin2007, McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Rodríguez, Quinoy, Arnold, Kendall and Weisz2018).

Perepletchikova and Kazdin (Reference Perepletchikova and Kazdin2005) have emphasized the need to examine the association between treatment integrity and treatment outcome and a successful outcome of an EBT depends in part on delivering the EBT with integrity (Waltz et al., Reference Waltz, Addis, Koerner and Jacobson1993). However, despite expectations that therapists’ competence and adherence should predict treatment outcomes, a meta-analysis on adults found no association between either competence or adherence and treatment outcomes (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Derubeis and Barber2010). This meta-analysis consisted of studies from a wide range of different psychotherapeutic treatment approaches, were based on adult populations and did not include children. When investigating the association between adherence/competence and treatment outcome in children and adolescent therapy, a systematic review and meta-analysis from Collyer et al. (Reference Collyer, Eisler and Woolgar2020) indicated a small, but significant positive relationship between therapist adherence and outcome, but there was no association between competence and treatment effect. Even though a relation between adherence and outcome was found, the small effect size for the associations between these two variables suggests that clinical outcome could be associated with other factors than adherence.

Understanding how treatment integrity relates to treatment outcome and if it could be upheld when an EBT is implemented in different clinical settings, would be helpful in training and supervision of therapists (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011) and ultimately also result in better treatment quality for patients. Some studies have investigated how EBTs could be implemented in community settings. McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Tully, Rodríguez and Smith2013) proposed that different components of treatment integrity (adherence, competence, alliance, client involvement, treatment differentiation) could be used as quality indicators of therapy with children and adolescents. Defining benchmarks for these indicators in clinical trials could serve as a guide when trying to specify quality of EBT, in order to translate EBT to community settings. Proctor et al. (Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011) proposed a taxonomy of eight distinct implementation outcomes: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration and sustainability. Several of these implementation outcomes could be used both to rate a specific treatment or to decide on which strategy to use when introducing a treatment into community settings. McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Tully, Rodríguez and Smith2013) and Proctor et al. (Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011) emphasized the need of developing instruments for assessing treatment integrity to disseminate EBT from research to practice.

Several measures of adherence and competence in CBT have been developed for use with adult populations (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Liese and Abrams2003; Barber et al., Reference Barber, Liese and Beck1995; Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001; Vallis et al., Reference Vallis, Shaw and Dobson1986; Young and Beck, Reference Young and Beck1980). A problem using such measures is that they may not generalize when assessing adherence and competence with paediatric populations. Two systematic reviews have been published that evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of assessment of treatment integrity in psychotherapy for children and adolescents (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Martinez and Southam-Gerow2019; Schoenwald and Garland, Reference Schoenwald and Garland2013). Although there are several integrity instruments, these instruments define integrity in different ways, which is problematic. Inadequate assessment of treatment integrity has also been emphasized as a major research problem by McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow and Weisz2009), which calls for more attention to these components to aid the dissemination of EBT in community settings.

Adherence and therapist competence related to manualized treatment have been measured differently across various CBT trials for children. Some studies have explored aspects of treatment integrity in manualized treatments with children as for example, the Coping Cat (Kendall, Reference Kendall1994) or ‘Friends for Life’ (Barrett, Reference Barrett2004; Barrett, Reference Barrett2008). The CBT Checklist (CBTC; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Gosch, Albano, Ginsburg and Compton2001) was developed to assess treatment integrity for the Coping Cat/C.A.T. Project programmes. The CBTC included an assessment of adherence to the manual, treatment implementation, and overall CBT skills (Podell et al., Reference Podell, Kendall, Gosch, Compton, March, Albano and Piacentini2013). The Treatment Integrity Support Materials for FRIENDS (Barrett, Reference Barrett2004; Barrett, Reference Barrett2008) evaluated adherence related to the content of each therapy session but did not include measure of competence. Limitations with these instruments are that they are constructed for a specific protocol/manual which limits generalization across other treatment protocols for the same disorder(s), and that they only assess limited aspects of treatment integrity.

Generic instruments that assess adherence and competence in CBT for youth also exist. The Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy Adherence Scale for Youth Anxiety (CBAY-A; Southam-Gerow et al., Reference Southam-Gerow., McLeod, Arnold, Rodríguez, Cox, Reise, Bonifay, Weisz and Kendall2016) is a 22-item instrument that assess adherence in CBT for youth anxiety. Four items cover the first area called Standard which represents common interventions in CBT sessions, 12 items cover the area Model which assesses model-specific content, and finally six items are related to the area Delivery, which measures how model items are delivered. Another instrument called Cognitive-Behavioural Treatment for Anxiety in Youth Competence Scale (CBAY-C) is designed to assess competence in delivering core elements in CBT when treating youth anxiety (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Rodríguez, Quinoy, Arnold, Kendall and Weisz2018). The CBAY-C consist of 25 items and uses the same content as the CBAY-A (Standard, Model, Delivery) when assessing competence. In addition, the CBAY-C also have two global item scores related to responsiveness and skilfulness of CBT delivery. Both of these instruments show solid psychometric properties (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Rodríguez, Quinoy, Arnold, Kendall and Weisz2018; Southam Gerow et al., Reference Southam-Gerow., McLeod, Arnold, Rodríguez, Cox, Reise, Bonifay, Weisz and Kendall2016). Both treatment and adherence were higher in research settings, where competence differed the most across settings. Results also suggested that the overlap between the CBAY-A and CBAY-C was moderate, indicating that these instruments measure different components of treatment integrity.

There is a need to explore adherence and competence in psychotherapy research using instruments with good psychometric properties (James et al., Reference James, James, Cowdrey, Soler and Choke2013). Bjaastad et al. (Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016) developed the Competence and Adherence Scale for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CAS-CBT). This instrument builds on and extends previous work related to the Cognitive Therapy Adherence and Competence Scale (CTACS; Barber et al., Reference Barber, Liese and Beck1995; Barber et al., Reference Barber, Liese and Abrams2003). The CAS-CBT is a measure of adherence and competence for CBT for youth anxiety. The scale is particularly suitable for manualized treatment protocols that have specific session goals that should be assessed.

An initial evaluation of the psychometric properties of the CAS-CBT (Bjaastad et al., Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016) was based on 181 videotaped sessions of 182 youth aged 8–15 years receiving individual CBT (ICBT) for anxiety disorders. Inter-rater reliability of adherence and competence was good (ICC = .83 for adherence and ICC = .64 for competence) and rater stability was high. The inter-rater reliability between the expert versus the non-expert raters was excellent (ICC = .83) for adherence and good (ICC = .64) for competence. A factor analysis of the CAS-CBT suggested a two-factor structure, with one factor consisting of items relating to CBT structure and session goals, and a second factor including items addressing process and relational skills (Bjaastad et al., Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016). As only one study to date has evaluated the psychometric properties of the CAS-CBT, research in other populations is warranted.

CBT is commonly delivered in different treatment formats, such as individual therapy or group therapy. For transference of results across different treatment formats, it is advantageous to have measures of treatment integrity that can be applied across different treatment formats. The present study expands on previous evaluations by also examining the psychometric properties of the CAS-CBT in both individual CBT (ICBT) and group CBT (GCBT). The aims of the study were therefore twofold; first to examine the reliability of the CAS-CBT for children with anxiety disorders treated in community mental health clinics, and second to explore if there were any differences on the CAS-CBT related to treatment format. Specifically, we wanted to examine (a) the internal consistency of the CAS-CBT, (b) the inter-rater reliability between expert and non-expert raters, and (c) the factor structure of the scale in individual and group formats.

Method

Participants

The participants were part of an effectiveness study of the Coping Cat programme for children with anxiety disorders (Villabø et al., Reference Villabø, Compton, Narayanan, Kendall and Neumer2018); 165 patients were included (mean age = 10.46 years, SD = 1.49, age range 7–13 years). Participants were referred to treatment by primary care providers or child protection service managers to five child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) clinics in South-Eastern Norway. Inclusion criteria were: (1) children between the age of 7–13 years; (2) a primary diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or social anxiety disorder (SOC) according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000); (3) significant functional impairment according to the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Gould, Brasic, Ambrosini, Fisher, Bird and Aluwahlia1983); (4) an IQ of 70 or higher; and (5) at least one parent had to be proficient in Norwegian. Exclusion criteria were: (1) mental health disorder with a higher treatment priority; (2) pervasive developmental disorder; (3) psychosis; and (4) current use of anxiolytic medication. After an initial assessment, eligible participants were randomized to either individual ICBT or GCBT.

Treatment

All treatment provided in ICBT and GCBT followed a Norwegian translation of the Coping Cat manual (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Martinsen and Neumer2006). Treatment in both conditions consisted of 12 child sessions and two parent sessions delivered over a 12-week period. Each child received training in anxiety-management skills and behavioural exposures to anxiety-provoking situations. Children randomized to GCBT met individually with one of the two group therapists for the first three treatment sessions before joining a group from session 4 onwards. Meeting with the therapist individually for the first three sessions allowed the therapist and child to get to know each other better, establish a therapeutic alliance, and enabled the therapist to better tailor the treatment to the needs of each individual child in the group. The GCBT approach consisted of 16 treatment groups, consisting of a mean of 4.63 participants in each group (range 3–5). A relatively low number of the children (6.6%) did not complete the treatment across both individual and group treatment.

Therapists

Five CAMHS clinics participated in the study, which covered both urban and rural areas in South-Eastern Norway. Mental health services were provided free of charge. Treatment was provided by 32 therapists (mean age = 34.7 years, SD = 5.9, range 27–49 years, 81.3% females) treating an average of five children each (range 1–19). Each clinic enrolled an average of 33 participants in the study, with a range of 17–45 participants. The therapists had a mean of 44.3 months of clinical experience (SD = 35.6, range 3–156), primarily in CAMHS. Twenty therapists were clinical psychologists, four were clinical social workers, six were MDs, and two were clinical pedagogues (i.e. who had an undergraduate degree in education with an additional two years of clinical training). All participating therapists completed 2 days of general training in CBT and specific training in the Coping Cat programme prior to the start of the study. The training consisted of a combination of lectures, practical exercises, and role plays. Study therapists were not required to have specific CBT training prior to the study. Therapists varied greatly in their experience delivering CBT for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children. Two therapists had completed a 2-year post-graduate CBT training programme, but the remaining therapists had little or no previous training in CBT, except for the 20 clinical psychologists for whom basic CBT skills were probably part of their standard education. Therapists varied in their theoretical orientation as well, describing themselves as eclectic, cognitive, cognitive behavioural, psychodynamic or family-orientated prior to the study. During the treatment phase of the study, therapists were offered monthly group supervision. The supervision typically focused on how to adequately apply the treatment manual and on parental involvement in the treatment. Additional supervision was available upon request, but few therapists took advantage of this offer. All therapists continued their ordinary clinical work in addition to the children treated in the treatment study. Most therapists provided both individual and group treatments. In GCBT, two therapists were assigned to each group.

Measures

The Cognitive Therapy Adherence and Competence Scale (CAS-CBT) is an 11-item scale (Bjaastad et al., Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016), with seven items assessing adherence and four assessing competence. The scale targets specific aims for each therapy session. All items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 6. Anchors for the adherence items range from ‘None’ (0) to ‘Thorough’ (6) and anchors for the competence items range from ‘Poor skills’ (0) to ‘Excellent skills’ (6). Additional items include global adherence (one item), global competence (one item), and how challenging the session appeared for the therapist (one item). The scale, including instructions for scoring, can be found at http://www.katsiden.no.

Rating of adherence and competence

The therapists’ verbal and non-verbal behaviours were assessed and rated using the CAS-CBT. Trained raters scored adherence with regard to what extent the therapist was able to perform the set tasks and goals of the session. Competence was evaluated on how well the therapist performed the tasks of each session rated. During the study, all CBT treatment sessions were video-recorded and a random sample of 212 sessions (13% of the total number of sessions) were rated with the CAS-CBT scale. In this study, the sessions were divided into two groups (early and late sessions) and randomly allocated to the raters. Five blocks of sessions from the first segment and five blocks from the latter segment were randomly allocated to the raters, who rated one block from each treatment segment each.

The selected video recordings included all the 32 study therapists and 126 (73.2%) of the 165 patients. Seven patients did not start the treatment, and four participants dropped out of the treatment after the first or second session and hence their sessions were not evaluated. Of the 212 videotapes, 110 (51.9 %) were recordings of individual treatment sessions and 102 (48.1 %) were recordings of group treatment sessions.

Five independent raters assessed the videos. The two expert raters assessed a total of 81 sessions (one rated 29, whilst the other rated 52 sessions) and three non-expert raters assessed a total of 131 sessions (36, 45 and 50 each). Expert raters were senior/experienced clinical psychologists, while non-experts were one less experienced clinical psychologist and two students. To better evaluate therapy sessions, all raters completed a 2-day workshop in the Coping Cat programme, if they had not received training in this treatment programme prior to participating in the study. However, raters did not participate as study therapists. In addition to the 2-day training in the Coping Cat programme, all raters completed a 1-day training in the use of the CAS-CBT, which was provided by one of the developers of the scale (author J.F.B.). The training included scoring and discussion of several training videos of therapy sessions. Initially, ten sessions were rated by both the expert and non-expert raters to establish reliability. Reliability confidence was assessed with discussions between the experts and non-experts reaching a consensus before they performed additional coding of the videotapes in the study. All five raters had to achieve satisfactory reliability (ICC greater than .80) before being allowed to code study sessions (Villabø et al., Reference Villabø, Compton, Narayanan, Kendall and Neumer2018).

Data analyses

Accuracy and interrater reliability

Intraclass correlations [ICC (2,1); Shrout and Fleiss, Reference Shrout and Fleiss1979] were calculated to measure inter-rater reliability between the five raters. The ICC model used in this study is the two-way random effects, absolute agreement, single rater measurement [ICC (2,1): Shrout and Fleiss, Reference Shrout and Fleiss1979]. A total of 16 sessions were rated by all raters. The ICCs were interpreted following Cicchetti’s guidelines (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994), where ICC<.40 reflects poor agreement, ICC between .40 to .59 reflects fair agreement, ICC between .60 and .74 reflects good agreement, and ICC≥.75 is considered to reflect excellent agreement.

Factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (principal axis factoring) with oblique rotation and Kaiser normalization, was conducted to explore the CAS-CBT scale both on the total sample and subsamples. Although there is a continuous discussion in the literature about whether to use exploratory factor analysis (EFA) or confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Kauffeld and Holton2007), an EFA was chosen because research in this area is sparse and there has been only one previous psychometric assessment of the newly developed CAS-CBT. We decided that our analyses were more data-driven based on one initial validation of the instrument rather than based on theory and research and therefore EFA was suitable for this study (Suhr, Reference Suhr2006; Worthington and Whittaker, Reference Worthington and Whittaker2006). The total sample (n = 212) and the subsamples (ICBT = 110, GCBT = 102) of videotapes were considered sufficient to perform the factor analysis (MacCallum et al., Reference MacCallum, Widaman and Hong1999).

Results

Adherence and competence scores for the therapists

The mean score of the 11 items on the instrument for both individual and group treatment for the therapists ranged from 1.57 to 5.86 (mean = 4.36, SD = 1.02) for adherence and 1.25 to 6.00 (mean = 4.50, SD = 1.06) for competence.

Inter-rater reliability

Interrater reliability of the n = 16 randomly selected videotaped sessions rated by all five raters showed excellent agreement for the total score the of 11 items (ICC = .813), excellent agreement for the adherence subscale (ICC = .872), and good agreement for the competence subscale (ICC = .633). An evaluation of the inter-rater reliability of each item revealed that eight of the 11 items achieved fair to excellent inter-rater reliability (ICCs ranged from .455 to .969), while three achieved poor reliability. These three included item 5 (positive reinforcement) with ICC = .359, item 6 (collaboration) with ICC = .138, and item 8 (process and relational skills) with ICC = .137. However, further analyses of reliability of these three items showed fair to good inter-rater reliability when rated only by expert raters (item 5, ICC = .665; item 6, ICC = .689; item 8, ICC = .561). Pairwise comparisons between possible pairs of expert and non-expert raters showed that on item 5 (‘positive reinforcement’), expert and non-expert raters gave the same score on two videos (12.5%), had a discrepancy of 1 on eight videos (50%), and a discrepancy of 2 on six videos (37.5%), suggesting moderate agreement between expert and non-expert raters on this item, even though the ICC was low. On item 6 (‘collaboration’), expert and non-expert raters gave the same score on two videos (12.5%), had a discrepancy of 1 on four videos (25%), and a discrepancy of 2 or more on 10 videos (62.5%), suggesting poor agreement between expert and non-expert raters on this item. On item 8 (‘process and relational skills’), possible pairs of expert and non-expert raters had a discrepancy of 1 in their ratings of 10 videos (62.5%) and a discrepancy of 2 or more on six videos (37.5%). The greatest discrepancy in ratings was among the non-expert raters. See Table 1 for details.

Inter-item correlations

The same 212 videos were used for the evaluation of inter-item correlations, internal consistency and factor structure (131 scored by non-expert raters, 81 scored by expert raters) of the CAS-CBT. Table 2 shows inter-item correlations for the 11 items of the CAS-CBT. The correlations were predominantly significant except the item ‘Parental Involvement’, which was not significantly correlated with any items besides the competence item ‘Cognitive Therapy Structure’ and the adherence item ‘Session Goals’.

There was a strong correlation between the summary scores for adherence and competence scales: r = .72, p<.001.

Table 1. Items included in the Competence and Adherence Scale for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CAS-CBT) for paediatric anxiety disorders and mean, standard deviation (SD) and ICC reliability coefficients for each item

Means and SD for the total sample of videos (N = 212) and videos scored for inter-rater reliability between student raters and expert raters (n = 16). Intraclass correlations (ICC) coefficients are based on the sessions assessed by student and expert raters (n = 16).

Table 2. Intercorrelations for the 11 scale items of the Competence and Adherence Scale for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CAS-CBT)

Item 1, homework review and planning new homework (adherence); Item 2, structure and progress (adherence); Item 3, parental involvement (adherence); Item 4, cognitive therapy structure (competence); Item 5, positive reinforcement (adherence); Item 6, collaboration (adherence); Item 7, flexibility (competence); Item 8, process and relational skills (competence); Item 9, session goal 1 (adherence); Item 10, session goal 2 (adherence); Item 11, session goals (competence). Pearson correlation, two-tailed; *p< .05, **p<.01.

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the CAS-CBT total score was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .88).

Factor analysis

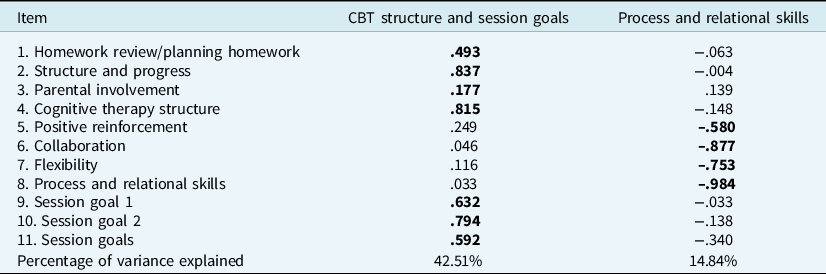

Based on the total sample of the videotapes (both ICBT and GCBT, n = 212) with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.84 (meritorious), the exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation found two factors with eigenvalues over Kaiser criterion of 1, which suggested a two-factor solution. These two factors explained 56.6 % of the variance. Table 3 displays the factor loadings after rotation. Factor 1 represents items related to CBT structure and session goals, whilst factor 2 represents items linked to process and relational skills.

To explore whether the same factor structure was found in the two different treatment conditions (ICBT and GCBT) a new exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation was performed separately in these subsamples. In the ICBT sample with a KMO = 0.80 (meritorious) results found two factors with eigenvalues over Kaiser criterion of 1, and two factors on the GCBT with a KMO = 0.83 (meritorious) separately. The ICBT sample (n = 110) suggested a two-factor solution with the same factors as described in the total sample where this explained 56.15 % of the variance. Table 4 displays the factor loadings after rotation for the ICBT factor analysis. The factor analysis of the GCBT sample (n = 102) also suggested the same two-factor solution as the total sample. The two factors explained 57.35% of the variance, and Table 5 displays the factor loadings after rotation for the GCBT sample.

Table 3. Summary of the exploratory factor analysis results (N=212 videotapes) for the 11-item competence/adherence measure rotated components loadings

Pattern matrix. Extraction method: exploratory factor analysis (principle axis factoring). Rotation method: Oblimin with Kaiser normalization. Factor loadings over .30 appear in bold. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy.

Table 4. Summary of the exploratory factor analysis results (N = 110 videotapes) for the 11-item competence/adherence measure: individual treatment only rotated components loadings

Pattern matrix. Extraction method: exploratory factor analysis (principle axis factoring). Rotation method: Oblimin with Kaiser normalization. Factor loadings over .30 appear in bold. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy.

Table 5. Summary of the exploratory factor analysis results (N = 102 videotapes) for the 11-item competence/adherence measure: group treatment only rotated components loadings

Pattern matrix. Extraction method: exploratory factor analysis (principle axis factoring). Rotation method: Oblimin with Kaiser normalization. Factor loadings over .10 appear in bold. CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of CAS-CBT in a clinical sample of children with anxiety disorders participating in a naturalistic out-patient clinical study. Results showed that the scale had good internal consistency and excellent overall inter-rater reliability. The factor analysis on the total sample showed a two-dimensional factor structure, where factor 1 was related to CBT structure and session goals, and factor 2 was linked to process and relational skills.

The inter-rater reliability showed excellent agreement for the total scale of the 11 items, excellent agreement for adherence subscale and good agreement for competence subscale. However, the items assessing positive enforcement, collaboration, and process and relational skills showed a larger discrepancy between experts and non-experts, which could be explained by the fact that these items are of a non-verbal nature, requiring more clinical skill and experience to assess in a reliable manner. The good internal consistency of the majority of the items might suggest that the items of the instrument are closely related. The findings from our study are comparable to Bjaastad et al. (Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016) as their study concluded with excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC = .83) for adherence and good reliability (ICC = .64) for competence. Findings from the present study and that of Bjaastad et al. (Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016) suggest that inter-rater reliability was higher for adherence than competence, which could suggest that it is easier to assess whether a therapist implements prescribed procedures, rather than the quality by which they are applied. McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Rodríguez, Quinoy, Arnold, Kendall and Weisz2018) reported an ICC range from 0.37 to 0.80 for CBAY-C and Southam-Gerow et al. (Reference Southam-Gerow., McLeod, Arnold, Rodríguez, Cox, Reise, Bonifay, Weisz and Kendall2016) described an ICC range of 0.43 to 0.93 for the CBAY-A. These results show that the interrater reliability was higher for adherence than competence, and that CBAY-C and CBAY-A showed a higher agreement between raters than that observed with the CAS-CBT in the present study.

There was a strong positive correlation between total adherence score and total competence score (r = .72, p<.001) in our study. This association between adherence and competence are in line with Bjaastad et al. (Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016), who also used the CAS-CBT, which reported a correlation of r = .79. At the same time, our correlations are higher than McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Rodríguez, Quinoy, Arnold, Kendall and Weisz2018), who reported mean level correlation coefficients of r = .55 between adherence and competence using the CBAY-A and CBAY-C. There could be several explanations for the strong correlation in our study beyond the simple possibility of normal statistical variation between datasets. One could be that raters might struggle differentiating adherence and competence items on the CAS-CBT. The specific distinctions between adherence and competence were specifically addressed with the raters throughout their training, but despite these efforts the correlation remained high. This may be explained by the same treatment components being rated for both adherence and competence. Another explanation could be that therapists who adhere to the treatment protocol are skilled therapists with high competence, but findings from studies such as McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Rodríguez, Quinoy, Arnold, Kendall and Weisz2018) and McLeod et al. (Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Jensen-Doss, Hogue, Kendall and Weisz2019) do not support this explanation. In order to investigate if these results are related to the psychometric properties of the CAS-CBT or the training of the raters, further research should include detailed descriptions, outlining examples of what behaviours constitute adherence versus competence for the protocol being evaluated and including training videos of the protocol being evaluated, using sessions where therapists are exhibiting different levels of adherence and competence (Bjaastad et al., Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016). Following such recommendations, raters may be able to differentiate the two to a larger extent. Another solution could be that adherence and competence might need to be rated separately by different raters to highlight the differences, but this is not an ideal solution as it requires more resources.

The factor analysis on the total sample showed a two-dimensional factor structure, where factor 1 was related to CBT structure and session goals and factor 2 was associated with process and relational skills. The factor structure observed in this study are in line with the results by Bjaastad et al. (Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016). Both of these two factors are highly related to provide high-quality CBT treatment for children. The first factor is related to ‘staying on track’ in therapy and to maintain a structure and focus on treatment goals. The second factor could reflect the concept of the therapeutic alliance dimensions of goals, tasks and bond (Bordin, Reference Bordin1979; Wampold, Reference Wampold2001). When analysing the two different treatment conditions (individual and group therapy), results showed the same two-factor solution.

The results indicated that non-expert raters can achieve adequate accuracy after assessment training. This suggests that non-expert raters could be used for such purposes if they are trained adequately, and their accuracy is checked throughout the rating process. Qualified clinicians will also need to complete training and accuracy testing to be considered as a potential expert raters.

Limitations

Although the results of the study are promising, there are some limitations. The high correlation between adherence and competence is problematic. One may consider whether it is the best use of rater resources to make them assess both adherence and competence, or if they should merely assess one or the other. Using such a design of ratings could help establish whether the high correlation is simply a product of using the same rater which could influence correlational data in this study. Due to the randomization of the videotapes, it is possible that the raters assessed the same therapist and patient on more than one occasion, which could be described as a potential rater confound suggesting that the sample might not be independent (von Consbruch, Reference von Consbruch, Clark and Stangier2012). This could potentially be improved by ensuring that each rater only assesses each therapist and patient once. In order to properly define and operationalize adherence and competence it would be preferable to have further studies including the CAS CBT, and also use more than one instrument measuring both adherence and competence to compare these results.

Conclusion

Researchers need to incorporate measures of treatment integrity when conducting clinical trials to explore how this may be related to treatment outcome (Perepletchikova and Kazdin, Reference Perepletchikova and Kazdin2005; Perepletchikova et al., Reference Perepletchikova, Treat and Kazdin2007; Southam-Gerow and McLeod, Reference Southam-Gerow and McLeod2013). Research suggests that instruments assessing adherence and competence in CBT can separate treatment provided in research settings and community clinics (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Jensen-Doss, Hogue, Kendall and Weisz2019). Effectively assessing and understanding underlying mechanisms in CBT for children is crucial in order to improve the quality of therapy provided to children (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Tully, Rodríguez and Smith2013; Schoenwald and Garland, Reference Schoenwald and Garland2013). When such knowledge is established, this could have an effect on CBT training and the implementation of evidence-based practice in community clinics (Rapley and Loades, Reference Rapley and Loades2019).

This is the first time CAS-CBT has been used for the manual-based Coping Cat treatment and includes both ICBT and GCBT. The results of this study are in line with an earlier study (Bjaastad et al., Reference Bjaastad, Haugland, Fjermestad, Torsheim, Havik, Heiervang and Öst2016) which suggests that CAS-CBT shows promising results when assessing therapist adherence and competence in CBT for children. The degree of little variability in the data suggests that CAS-CBT can be learned and mastered quickly by raters and therefore is easy to implement. In the present study, the CAS-CBT showed good internal consistency and excellent overall inter-rater reliability, despite some discrepancy in ratings among the non-expert raters. Additionally, the subsamples of ICBT and GCBT show the same factor solution as the overall sample. The results from this study show that the CAS-CBT can be used across a range for therapy formats, including individual and group therapy.

In future research when employing the scale, it is recommended that the raters are thoroughly trained and assessed for accuracy. Raters should also have a comprehensive understanding and knowledge of the treatment interventions to assess adherence and competence in a successful manner. As assessment of adherence and competence could both be expensive and time-consuming, the results of this study indicate that when using CAS-CBT advanced students with basic CBT knowledge and experience can be used as raters, which is very promising. Future research should also explore if the CAS-CBT could be used on treatment which is not manual-based and explore differences and similarities to other treatment integrity instruments like the CBAY-C and CBAY-A. There is a need for studies on the validity of the scale, and other instruments such as CBAY-C, CBAY-A and CAS-CBT to evaluate the same treatment sessions to assess convergent validity.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S.H. The data are not publicly available because the contained information could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This work was supported by Stiftelsen Dam, Norway (grant number 2016FO75751).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00735995) and approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway (reference no. 2.2008.559).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.