Introduction

Client experience of therapy has occupied a central role in Person Centered Counselling and Process Experiential Therapy research, beginning with Carl Rogers’ (Reference Rogers1951) study of client diaries. Client reports of their experiences during therapy offer valuable information on how to maximize the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic modalities (Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Baker, Boutselis and Chiswick2010) and provide insights into the complex and multidimensional ways in which individuals experience and respond to therapy. Indeed, a meta-analysis of studies of the effects of clients providing client feedback about their experiences has been shown to have a small but significant positive effect on short-term mental health outcomes (Knaup et al., Reference Knaup, Koesters, Schoefer, Becker and Puschner2009). Carl Rogers acknowledged that client-reported helpfulness could provide a useful pan-theoretical factor to capture the therapeutic climate as it is generated in session (Rogers, Reference Rogers1958). It has been employed in a number of previous Person Centered Counselling studies to pinpoint active ingredients of therapy (e.g. Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Baker, Boutselis and Chiswick2010), culminating in a list of client-reported helpful events and impacts, which appear to map onto aspects of therapy across different disciplines.

To date, a variety of constructs have been employed in an attempt to understand what clients report as helpful about their experiences in therapy and why. Perceived helpful factors are often conceptualized as aspects of alliance formation and development (Bachelor, Reference Bachelor1995; Bedi, Reference Bedi2006; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Reese, Quirk and Rodolfa2013; Simpson and Bedi, Reference Simpson and Bedi2013). This has been established through client reports of critical incidents, significant or positive moments and helpful events (Bedi et al., Reference Bedi, Davis and Meris2005; Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Baker, Boutselis and Chiswick2010; Elliott, Reference Elliott1985, Levit et al., Reference Levitt, Butler and Hill2006; Llewelyn et al., Reference Llewelyn, Elliott, Shapiro, Hardy and Firth-Cozens1988; Timulak and Lietaer, Reference Timulak and Lietaer2011); known as the ‘events paradigm’. Interpersonal Process Recall (IPR) (McLeod, Reference McLeod2001; Elliott, Reference Elliott, Greenberg and Pinsof1986) is a key example of this method. IPR supports the use of video-assisted recall to investigate the therapy process. The method has principally included qualitative methods to gather client descriptions of helpful events or factors using semi-structured or open-ended interview.

The most commonly identified event impacts included the client gaining a new perspective, attitude or insight, the development of a new understanding of self or others, or an increase in self-awareness (Bachelor, Reference Bachelor1995; Elliott, Reference Elliott1985; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Cooper, McArthur and McLeod2012; Paulson et al. Reference Paulson, Truscott and Stuart1999; Llewelyn et al., Reference Llewelyn, Elliott, Shapiro, Hardy and Firth-Cozens1988). In several studies, insight learning or gaining a new perspective was the largest and most internally consistent change factor. This was associated with a therapeutic environment that facilitated client comfort (Bachelor, Reference Bachelor1995), emotional support, personal contact and reassurance (Mohr and Woodhouse, Reference Mohr and Woodhouse2001). Client Self Disclosure (having someone to talk to, telling someone about skeletons in the closet, speaking to someone neutral and feeling safe to say what the client wanted to say) was rated highly by clients, particularly in studies that did not employ predetermined coding schemes (Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Truscott and Stuart1999; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Cooper, McArthur and McLeod2012). The remaining categories of helpful client processes have included reaching a definition or the clarification of problems (Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Baker, Boutselis and Chiswick2010; Elliott, Reference Elliott1985; Elliott and Wexler, Reference Elliott and Wexler1994) and problem solution (Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Baker, Boutselis and Chiswick2010; Elliott, Reference Elliott1985; Llewelyn et al., Reference Llewelyn, Elliott, Shapiro, Hardy and Firth-Cozens1988; Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Truscott and Stuart1999).

The majority of research in this area is qualitative in nature, although logistic regression has been used to test for differences in the level of helpfulness and hindering between categories of events and their impact and content (Castonguay et al., Reference Castonguay, Boswell, Baker, Boutselis and Chiswick2010; Elliott, Reference Elliott1985). Three studies have included additional pre- and post-outcome measures, such as the WAI short-form (Horvath and Greenberg, Reference Horvath and Greenberg1989), SCL-10 (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Attkisson and Stegner1983), and Global Rating Scale (Green et al., Reference Green, Gleser, Stone and Seifert1975). Yet, across the literature, no studies to date appear to have captured quantitative continuous data with regard to client process variables that could be used to test experimental hypotheses. Although segments of change over a shorter time period have been analysed using IPR, change was rarely studied over the course of a whole session, due to the intensive nature of the analysis. The use of static measures may not capture change processes (developing insight, awareness and reflexivity through exploration and self-disclosure) identified by clients as being active in therapy (Levitt et al., Reference Levitt, Butler and Hill2006). Client ratings have been collected at a small number of fixed time points over the duration of multi-session treatment, which does not allow for detailed analyses of within-subject effects and processes that unfold over time (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Cahill, Barkham, Gilbert and Leahy2007).

In the current study we piloted a new method of assessing client feedback, which holds a number of potential advantages. First, it utilized video feedback to allow clients direct access to the session without having to rely on memory. Second, the client was asked to report on their experience of therapy in terms of key psychological constructs when the video was paused every two minutes. This provided multiple data points each session to allow change during a session to be inspected visually, and for multi-level analyses to be conducted. We examined the concurrent validity of this method; namely, does client helpfulness co-vary with the psychological factors proposed to be effective in psychotherapy? Due to the very nature of this methodology, it was not appropriate to examine inter-rater reliability (the measures were reports of client's own experience) or test–retest reliability (the measures were meant to vary between assessment points). We also prioritized the brevity of single item measures of constructs over the possible advantages of establishing internal reliability through the use of multiple items.

A number of constructs were informed by psychological theory, supported by earlier research. The theoretical framework that specifically informed the current work was perceptual control theory (PCT; Powers, Reference Powers1973) because it offers a pertinent framework for understanding what is helpful in therapy. It also provides an explanatory model of how change mechanisms operate that can be applied to a quantitative methodological design. The therapy we analysed in this study is also a direct application of PCT, known as the method of levels (MOL; Carey, Reference Carey2006; Carey, Mansell and Tai, Reference Carey, Mansell and Tai2015).

PCT describes a hierarchy of control systems that detects discrepancies between an internal standard of how the person would like or needs things to be (e.g. a goal or value that feels ‘just right’) and what the individual perceives to be happening. Behaviour is the means by which a person reduces discrepancy between their perception and their desired goal. Emotional disturbance is experienced when goals are in conflict because actions used to pursue one goal blocks the other, and subsequently neither goal is sufficiently accomplished (Powers, 2005). Psychological distress builds up when conflict between goals remains unresolved. Distress is alleviated when conflict is resolved, which occurs through a trial-and-error learning process known as reorganization. Because reorganization operates through trial and error, it must be directed towards the system governing the goal conflict and sustained there until spontaneous changes are made intrinsically that reduce the conflict, and ultimately, the distress. Reorganization follows awareness, and talking freely for a period of time about an emotionally salient topic is a clear marker that awareness is directed and maintained on goal conflict, thus increasing the chances of reorganization occurring.

MOL therapy is a client-led, transdiagnostic cognitive therapy based on PCT. Importantly, the ultimate aim of the therapy is to help the client regain control. In order to achieve this, the client is encouraged to talk freely about their problems, and they are regularly asked about their ‘disruptions’ as they are talking. These might include shifts in affect, pauses, emphasizing certain words, for example. In doing so, the client is helped to shift and sustain their awareness to goal conflicts and associated emotions that they are experiencing. This facilitates reorganization, involving a shift in perspective on their problems, and leading to therapeutic change.

Given the above account, we selected client perceived control, the ability to talk freely, the capacity to experience emotion and seeing a problem in new ways as our theoretically derived constructs, in light of evidence reviewed earlier which demonstrated that clients perceived these factors as helpful. We also included several facets of the quality of the therapeutic relationship, given the modest association between therapeutic relationship and clinical outcome (Strupp, Reference Strupp2001; Norcross, Reference Norcross2011).

Method

Ethics

We abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the American Psychological Association (APA). The study received local ethics (reference number 13/NW/0366) and research and development approval. Client participants had at least a week to consider participation and were informed the research would not affect their routine treatment. Routine treatment for all clients consisted of six 30-minute sessions of MOL therapy. Clients were first approached by a member of the primary care staff team and given a copy of a participant information sheet to read in their own time. This information detailed the procedure of the study, the level of their involvement, confidentiality and the benefits and risks of participation to the client. Clients were made aware that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. Written consent was obtained from participants by a member of the service staff team. Consent was also provided by therapists using a form collected by the chief researcher.

Participants

Seven therapists from the same primary care service participated in the study (six females and one male). Therapists were all qualified in delivering psychological therapies with varying levels of experience [a clinical psychologist, a mental health nurse with training in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and several psychological wellbeing practitioners]. The length of service in mental health services ranged from 5 to 20 years. Five therapists described their main theoretical orientation to be CBT, and two therapists reported a preference for psychodynamic therapy. All therapists participating in the study provided MOL therapy as routine treatment; no other model of therapy was offered. Clients in this service were typically offered six 30-minute sessions of therapy, but clients do not always attend all the sessions they are offered and there is some flexibility to extend therapy when required. Therefore the number attended ranged from one to eight sessions (mean = 5.5, SD = 1.8).

Client participants were recruited via the participating primary care service. A target of 23 client participants was identified for recruitment, in order to estimate a correlation coefficient of 0.5 (medium effect size) between the explanatory variables and perceived helpfulness with 80% power at a significance level of 0.05. Inclusion criteria were as follows: clients in treatment at the participating primary care service, who could identify a problem that they would like to work on and met service criteria for mild/moderate depression or mild/moderate anxiety disorder on GADS-7 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) and PQH-9 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), with sufficient English language skills to understand the therapist and the materials. ‘Sufficient English language skills’ were judged on whether the client was able to participate in the research without the aid of an interpreter. Clients with current suicidal intentions, severe self-injury, psychotic symptoms, current substance dependence, or organic brain impairment (e.g. dementia) were excluded from the study. A total of 38 clients consented and 15 participants withdrew before videotaping a therapy session. Many of the clients initially approached for the study said that they had declined because they felt anxious about videotaping a session. A total of 23 client participants recorded a therapy session with a therapist at one of three local clinic sites attached to the primary care service. Three clients decided to withdraw when contacted to complete the ratings session due to changes in their personal circumstances. Clients were recruited at different stages of their treatment. The number of sessions received prior to the test session ranged from one to eight (mean = 3.44, SD = 2.03). Four of the therapists saw one client each, one therapist met with two clients and the two remaining therapists met with six clients each.

A total of 18 clients completed the video-assisted rating. Client age ranged from 26 to 70 years (mean = 43, SD = 14), the majority were White British (88.89%) and included 12 males and six females. Overall, clients’ presenting problems were categorized by primary care staff during screening as (i) mixed anxiety and depression disorder (n = 11), (ii) depressive episode (n = 3) or (iii) mental disorder not otherwise specified (n = 4). Some of the clients met with the therapist that they were already seeing for routine treatment (n = 9) and others met with a new therapist that they had never met before (n = 9).

Measures

Standardized Measure of Relationship: Session Rating Scale (SRS). The SRS (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Miller, Sparks, Claud, Reynolds, Brown and Johnson2003) is a four-item measure of therapeutic relationship and is designed for practical use. The SRS has a moderate relation to the gold standard measures of the relationship such as the Working Alliance Inventory (Horvath and Greenberg, Reference Horvath and Greenberg1989) and the Revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire II (HAQ-II; Luborsky et al., Reference Luborsky, Barber, Siqueland, Johnson, Najavits, Frank and Daley1996), has good test–retest reliability (r = .64 to .70), convergent validity with the HAQ-II (.39 to .44) and feasibility (participant compliance of 96%) according to Duncan et al. (Reference Duncan, Miller, Sparks, Claud, Reynolds, Brown and Johnson2003). The SRS is based on Bordin's description of the alliance (Bordin, Reference Bordin1979) and is supported by evidence that suggests it represents the single underlying factor of the ‘strength of the alliance’. The items from the SRS are: (i) a measure of the relationship (feeling heard, understood and respected) with the following extreme ends of the scale: ‘not at all’ to ‘completely’, (ii) goals and topics (whether the client worked on and talked about what they wanted to): ‘not at all’ to ‘entirely’), and (iii) the approach of the therapist (whether it was a good fit for the client): ‘not at all’ to ‘completely’. The measure is usually administered post-session and so it was adapted to be administered at two-minute intervals, dropping the last item (iv) which asks the client if there was anything that was missing overall from the session.

Novel client ratings

Novel client ratings (with instructions for participants shown in the Appendix) were designed as bespoke process measures for the current study using a scale that was adapted for use from the format of the SRS (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Miller, Sparks, Claud, Reynolds, Brown and Johnson2003). The wording was changed to reflect the components of therapy that were being investigated as part of the current study. Five process items were presented to the client as a series of bipolar Likert scales with adjectives at each end. The items were a measure of (i) the extent of perceived therapist helpfulness: ‘not helpful at all’ to ‘extremely helpful’, (ii) the client's perceived sense of control over what was happening in therapy: ‘no control at all’ to ‘complete control’, (iii) the client's perceived ability to talk freely about their problem without filtering what first came to mind: ‘not able at all to ‘entirely able’, (iv) the client's perceived ability to experience emotion connected to the problem: ‘not able at all’ to ‘entirely able’, and (v) the client's perceived ability to see their problem in new ways: ‘not able at all’ to ‘entirely able’. All of the items were presented as a series of 10 cm lines on a single page with items from the SRS presented underneath. Eight client measures were completed at each time interval for every two-minute section of the therapy session watched on video.

Symptom measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) were used as symptom measures. The PHQ-9 is a reliable and valid brief measure of depression severity that is commonly used in guiding treatment decisions and in research. The measure consists of nine items with a total possible score of 27. A score above 10 indicates the threshold for clinical intervention. The GAD-7 is a standardized measure of anxiety-related disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder that has good psychometric properties (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). The GAD-7 is a 7-item measure with possible scores ranging from 0 to 21, with a threshold of 8 indicating the need for a clinical intervention.

Client symptom scores (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) were calculated at three time points; time point 1 (T1) at the start of the first therapy session, time point 2 (T2) at start of the rating session, and time point 3 (T3) at the start of the last session (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary statistics for scores on client variables

Therapist adherence

To establish a baseline adherence level for each therapist, two raters from within the research team rated therapist adherence to the MOL therapy model using the MOL Adherence Scale (MOLAS V2; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Carey and Tai2012) and the Cognitive Therapy Scale Revised (CTS-R; Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001). Raters were both experienced clinicians who had used MOL and CBT for several years and had been involved in the development of the adherence measure. The CTS-R is a 12-item scale to assess competence of therapists conducting cognitive therapy with good reliability and internal consistency (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001). The Likert scale items are scored from 0 (non-adherence) to 6 (very high skill). For the purposes of the current study, items 1 and 12 were omitted as agenda setting and homework were not relevant to the sessions being recorded for research. The MOLAS V2 is a 6-item measure that is based on the format of the CTS-R (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Carey and Tai2012). Ratings were based on review of the video material collected. One video per therapist was selected at random by the chief researcher to be rated. The kappa level of inter-rater agreement for therapist scores on the MOLAS was .58, (mean = 23.21, SD = 3.8) and .60 (mean = 33.64, SD = 7.08) on the CTS-R, which represents a modest level of inter-rater agreement.

Supervision and training

All of the therapists selected for the study attended an initial workshop day in MOL cognitive therapy run by experienced qualified clinicians. Throughout the study, a further series of training workshops (n = 4) and peer supervision sessions (n = 3) were held. During these sessions the therapists also completed ratings of therapy videos using measures of adherence and helpfulness, which gave them further opportunities to review and reflect on their own practice.

Procedure

Prior to the research session taking place, clients met with a therapist from the study to complete service measures of risk and distress (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) and to raise any questions. The researcher went through the information sheet, which explained the aims of the study and important details such as the confidentiality of their recordings, and the fact that the client and the therapist would view the video of the therapy separately. A session of therapy was arranged for a later date, which formed the first phase of the research. During this session the client met with a therapist for 30 minutes. Five minutes were allowed to start the session and another five minutes to arrange a further appointment at the end. Twenty minutes of therapy in total were video-recorded. Clients were allowed to talk for slightly longer so that a natural place to end was found and the video clips were later edited down to 20 minutes. The therapist then arranged a time for the client participant to attend a session to review the therapy video and complete ratings with the researcher on another day (preferably within 3 weeks of their therapy session).

In phase 2, clients were invited to meet with the chief researcher at one of the primary care sites in a private room to complete ratings of their recorded therapy session. The client completed routine service measures of risk and distress (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) and was provided with a booklet of measures to complete, which included the items specific for research. This booklet included the process measures and items from the SRS presented as ten separate pages of the same eight Likert scale measures. Instructions were given to the client to read the items carefully and complete each page after watching a two-minute segment of their therapy video on the laptop. The items were carefully explained to each client by the chief researcher using examples that were guided by a script. It was made clear to the client that their responses would not be passed on as feedback to their therapist. The client was provided with headphones so that they could absorb themselves in the material on video. The researcher paused the video playback every two minutes and asked the participant to complete a page of the measures. The researcher asked the participant to pay attention to any subtle changes in the measures in between sections. Clients were asked to rate according to what they could remember they had thought and felt at the time, rather than how helpful this now seemed in retrospect. The researcher then ended the session by engaging the client in a brief conversation about their experience of participation and went through confidentiality and any other client concerns.

Statistical analyses

A descriptive analysis was conducted on the client data in SPSS (2007). Overall, the data showed a non-normal distribution with a significant negative skew using the sktest in Stata (Reference Stata2011). The descriptive statistics revealed that there was sufficient variation in the sample scores for a multi-level analysis to be conducted. This follows guidelines set out by Heck and Thomas (Reference Heck and Thomas2009), that multi-level modelling requires more than 5% variation in outcomes across groups (in this case across subjects). In addition, we checked the potential for multi-co-linearity in our measures by calculating the tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) for each item. This revealed no concerns as all tolerances were above .25 and all VIFs were between 2 and 4.

The structure of the data suggested that a two-level mixed-effects model was most suitable to capture individual change over time within the context of the sample. Specifically, the two levels in the design were participant (between individuals) and time point (within individuals). We used a model that specified all of the variables in the following order: helpfulness with control, emotion, talk, perspectives, relationship (SRS), goals/topics (SRS) and approach (SRS). This statistical analysis allowed independent effects of each construct on helpfulness to be reported.

Each of the 18 client participants were required to complete 80 question items for the study (eight items at 10 time points over a 20-minute session). This meant that there were a potential total of 1440 client-recorded observations for the entire study. Missing data was recorded for two clients who completed 9/10 pages of the answer booklet (forgetting to fill out the last page) and one client (client 2) missed out a further two items at T2. The missing data were left blank as there were such a small number of missing items (items that the client had overlooked whilst turning the pages) that it was considered unlikely to affect the result.

Results

Clinical outcomes

A significant difference was found in GAD-7 scores between T1 (time of first therapy session) (mean = 13.61, SD = 6.22) and T3 (time of last therapy session) (mean = 6.61, SD = 5.75), t (17) = 4.32, p = <.001. There was also a highly significant difference between PHQ-9 scores at T1 (mean = 13.61, SD = 6.22) and T3 (mean = 6.61, SD = 5.75), t (17) = 4.30, p = <.001. At T1, 13 out of the 18 client participants (72%) had scores that were over the clinical threshold for depression on the PHQ-9, and 15 out of the 18 clients (83%) met the clinical threshold on the GAD-7 for anxiety disorder. At the time of the rating session (T2), seven out of the 18 clients (39%) met the clinical threshold for depression on the PHQ-9, and nine out of the 18 clients (50%) met the clinical threshold for anxiety disorder on the GAD-7. At T3, three of the 18 clients (17%) met the clinical threshold for depression (PHQ-9), and four of the 18 clients (22%) met the clinical threshold for anxiety disorder on the GAD-7.

Client ratings of the session

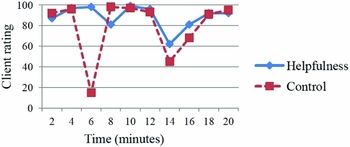

Figures 1 and 2 show two selected examples of individual client data. We have shown these for the reader in order to illustrate how one measure of a psychological construct (client control) and client-perceived helpfulness changed over time within an individual.

Figure 1. Example of client-rated scores for perceived helpfulness and control over the course of the session recorded at 2-minute intervals

Figure 2. A second example of client-rated scores for perceived helpfulness and control over the course of the session recorded at 2-minute intervals

Figure 1 shows that the scores on levels of helpfulness were reported as consistently high with a slight decrease in helpfulness following a more significant fall in reported control scores. This was followed by a dramatic reduction in control around 6 minutes and a slight decrease in perceived helpfulness.

Figure 2 shows that scores for helpfulness and control are roughly similar until 6 minutes, followed by a decline in control and a sharp fall in the level of helpfulness. Both variables then rise together to levels slightly higher than previously. At 16 minutes there is a fall in control once again, which is followed by a less dramatic decrease in helpfulness.

Table 1 shows the summary statistics for mean client scores on the dependent variable (helpfulness) and the seven client process variables. Overall, the mean scores for the client process variables were at the higher end of the scale and in the last quartile, suggesting that clients perceived their experience of therapy to be very positive. This was the case for the majority of clients, except for one client who reported consistently low scores.

Table 2 reports the zero-order inter-correlations for all seven variables. All variables correlated with helpfulness and with each other, indicating substantial concurrent validity. No correlations were in the very high range, with the exception of relationship and approach.

Table 2. Zero order correlation coefficients between client variables

H, helpfulness; TA, therapist approach; R, relationship; GT, goals and topics; TF, talking freely; E, emotion; C, control.

Regression analyses for each independent variable

The results of the planned strategy for the analysis in which all seven variables were entered into a regression are shown in Table 3. The regression revealed independent contributions of control, talking freely and therapist approach in predicting client perceived helpfulness.

Table 3. Summary of regression coefficient for client variables and helpfulness

The correlations that remained significant (where the confidence interval did not include 0) are shown in bold.

Discussion

The novel video methodology in the current study was found to be a feasible approach and acceptable to participants, with very little missing data. It also showed good evidence of concurrent validity, with client-rated helpfulness correlating with all of the psychological constructs examined. In the final mixed-effects regression analysis, it was therapist approach, control and talking freely that remained as the most robust predictors of client-perceived helpfulness. The method proposed by the current study answers the call from authors (Timulak, Reference Timulak2010; Norcross, Reference Norcross2011) for a quantitative approach to process therapy research that incorporates an explanatory framework for the mechanisms of change. The method provides an in-depth and micro-level inquiry of what happens during a therapy session and how clients experience this. We see no reason why the methodology could not extend to other client-rated constructs to test a range of theory-driven hypotheses regarding the conditions for psychological change.

With regard to the multi-level design, it is suggested that further analysis of the data using centering techniques to decompose within and between group effects could improve the specificity of the findings. This would provide more clarity on whether the associations between perceived control, ability to talk freely and helpfulness reflect something that unfolds during the session, or something about the differences between clients, or a possibly a combination of the two. Unfortunately, due to the number of data points it was not possible to conduct a time series analysis as part of this study; however, this would merit further investigation if the design were repeated. The measures were selected to be single items in order to reduce participant burden; the ratings were conducted every two minutes for a 20-minute session. The use of single items may also have helped clients to focus their attention on the two-minute segment of the session and be highly specific about what exactly they were rating at face value (control, helpfulness, talking freely, etc.) – rather than using variable questions to tap into a hypothesized latent construct, as is typical of longer trait self-report measures. An alternative design to improve the internal reliability of the measures would be to make the scale three or four times as long so that Cronbach alpha values could be calculated and the mean score of multiple items used. The respective strengths and limitations of these two alternative designs remains to be examined.

The number of sessions that clients engaged in prior to taking part in the study and their stage of treatment may have influenced what participants identified as helpful (Hill, Reference Hill2005). Due to the sampling of only one session in this study, it was not possible to explore this further. Half the participants had also already established a relationship with their therapist which could have affected their ratings. There were also twice the number of males to females in the sample and a lack of participants from ethnic and cultural minorities. It is also likely that the process of videoing the therapy session may have influenced how the client and therapist related to one another. For example, clients may have been less willing to disclose important sensitive information on video, despite knowing that the contents were confidential. The number of therapy sessions that clients received before taking part in the research varied, which may have had an impact on what they chose to talk about and the extent to which they rated their session as helpful. Future research could examine whether the findings here generalize to other forms of psychotherapy and attempt to replicate the findings over longer periods of therapy.

The results of this study provide some intriguing insights into how clients perceive their experience of therapy, what they consider to be helpful and what might lead to intra-individual change. The analysis of the data also lends support to a PCT framework that identifies client control as helpful for effective therapy. This form of methodology may promote the emergence of a more detailed understanding of what may help the clinician to respond to the client on a moment-to-moment basis, thus making it possible to understand resistance or facilitate gains more effectively.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest with regards to this publication.

Appendix Novel Client Measures (page 1 of 10 repeated measures)

Instructions: Read the questions carefully below. Each time the video is stopped, think about the 2 minutes of interaction that has just taken place between you and the therapist. Try to recall how you perceived what was going on at that time. Mark with an X on each vertical line the level which describes your own experience of each item.

(1) Therapist assistance

Not helpful at all |———————————————–——————————————–—–| Extremely helpful

(2) Sense of control over what is happening in therapy

No control at all |———————————————————–—————————————| Complete control

(3) Talking freely about my problem (without filtering what comes into my mind)

Not able at all |———————————————————————————————————| Entirely able

(4) Feeling able to experience emotion connected to the problem

Not able at all |——————————————————————–————————————–| Entirely able

(5) Being able to see my problem in new ways

Not able at all |——————————————————————–————————————–| Entirely able

(6) Relationship

I did not feel heard, understood and respected at all I felt completely heard, understood and respected

|——————————————————————–————————————–|

(7) Goals and topics

We did not work on what I wanted to talk about at all We worked and talked about what I wanted entirely

|——————————————————————–————————————–|

(8) Approach and methods

The therapist's approach is not a good fit for me at all The therapist's approach is an extremely good fit for me

|——————————————————————–————————————–|

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.