Introduction

There is a paradoxical lack of research and development (R&D) regarding clinical supervision, considering its essential role in the development of mental health professionals. Supervision is also a sophisticated professional activity, meriting due attention: “Cognitive therapy supervision can be as complex and challenging as cognitive therapy itself. Thus it is surprising that so little has been written about cognitive therapy supervision” (Liese and Beck, Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997, p. 114). In the Handbook of Psychotherapy Supervision (1997) (which also reviewed non-CBT approaches), Watkins summed the paradox up by noting that “something does not compute” (p. 604). As a result of this gap between theory and practice, it is thought that most supervisors rely on how they themselves were supervised (Falender and Shafranske, Reference Falender and Shafranske2004), or on applying what they do in therapy to their supervision (Milne and James, Reference Milne and James2000; Townend, Iannetta and Freeston, Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002).

The reflexive approach

Relying on past supervisors as a model for one's practice is fraught with difficulty, as errors may be perpetuated (Worthington, Reference Worthington1987), practice is unlikely to benefit from R&D, and training in supervision will lack an evidence-base (Spence, Wilson, Kavanagh, Strong and Worral, Reference Spence, Wilson, Kavanagh, Strong and Worral2001). In support of this assumption, when Townend, Iannetta, Freeston and Hayes (Reference Townend, Iannetta, Freeston and Hayes2007) repeated their UK survey of CBT supervisors after a 5-year interval, they found no clear evidence of improved supervisory practices. By contrast, applying what we do in therapy to supervision (reflexivity) has the advantage of connecting our supervisory practice to a guiding theory and to established techniques. In CBT this is a particularly strong tradition, as indicated consistently in the reviews by Perris (Reference Perris1993, Reference Perris1994), Padesky (Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996), Liese and Beck (Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997), Pretorius (Reference Pretorius2006), Lomax, Andrews, Burruss and Moorey (Reference Lomax, Andrews, Burruss, Moorey, Gabbard, Beck and Holmes2005), and Armstrong and Freeston (Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006). These reviewers have detailed the principles of CBT, showing how they apply to CBT supervision, which I have summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. A summary of the principles of CBT supervision, extended with concepts from evidence-based supervision (underlined)

According to this reflexive approach, CBT supervisors aim to specify problems, set the agenda collaboratively, ask questions (and so on), just as they would in therapy. However, it is argued that this kind of reflexivity is an inadequate response to the supervision paradox, as it may ignore valuable ideas from the general supervision literature, and related resources. To illustrate this point, Table 1 adds material from developmental and other non-CBT models of supervision (underlined); draws on the wider educational/training literature; and specifies two new principles (i.e. adding the need for context and R&D), in order to reflect distinctive features of CBT. In this way, we can usefully augment the concept of CBT supervision, enriching it with compatible ideas from neighbouring approaches. All of the augmentations within Table 1 are described more fully in Milne (Reference Milne2009). Examples of these innovations in CBT supervision are provided below.

In addition, it appears that the reflexive approach under-estimates supervision as a discrete competence domain. Liese and Beck (Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997) are not alone in viewing supervision as meriting special attention. Holloway and Wolleat (Reference Holloway and Wolleat1994) noted that, “because the goal of supervision is to connect science and practice, supervision is among the most complex of all activities” (p. 30). In particular, Falender and Shafranske's (Reference Falender and Shafranske2004) text advances the case for treating supervision as a specialized area of professional activity, noting that: “the practice of supervision involves identifiable competencies which can be learned” (p. 4).

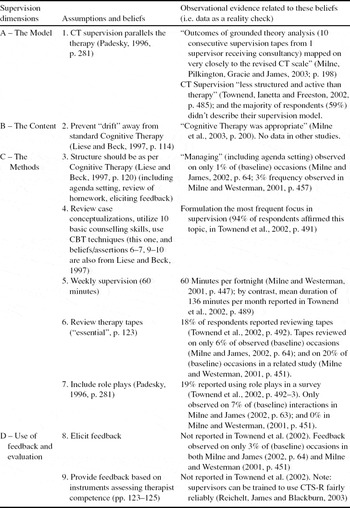

A final criticism of reflexive CBT supervision is that it may not be conducted with fidelity. This seems likely because supervisors only have these general principles as a guide, training is limited, and because of limited R&D to specify the approach. It follows that it is hard to design supervisor training, or to provide corrective feedback in a suitably informed way (e.g. there is no published measure of competence in CBT supervision). To examine this hypothesis, all known empirical analyses of CBT supervision were scrutinized. For example, the assertion that “cognitive therapy supervision parallels the therapy” (Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996, p. 281) was tested by reference to a grounded theory analysis (Milne, Pilkington, Gracie and James, Reference Milne, Pilkington, Gracie and James2003), and in relation to a survey of CBT supervisors within The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP; Townend et al., Reference Townend, Iannetta and Freeston2002). Similarly, the other main headings used to characterize CBT supervision are listed in Table 2, with the available evidence.

Table 2. Evidence of poor fidelity in existing observations of CBT supervision

Table 2 presents a disappointing picture, with mixed fidelity in terms of (A) the model, good fidelity regarding (B) the objectives, and one of the (C) methods (4: case conceptualization), but weak adherence for the remaining six tests of the assertions made within the cited review papers (i.e. as listed in column 2 of Table 2). For example, regarding (B) the objectives of CBT supervision, Liese and Beck (Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997) believe that it should prevent drift, and the study by Milne et al. (Reference Milne, Pilkington, Gracie and James2003) provided corroboration. By contrast, therapy tapes should be reviewed in CBT supervision, but this appears to be infrequent (C6). In summary, it would seem from this small but searching analysis that poor fidelity is indeed a problem with the reflexive approach.

The specialist in supervision

For the reasons noted above, it would be timely to supplement reflexive CBT supervision with a specialist approach. In addition to recognizing supervision as a discrete competence domain, this would extend the repertoire of CBT supervisors, increase the likelihood of carrying out supervision with fidelity, and provide it with a broader educational foundation. In order to illustrate the specialist approach, I will now indicate how the novel principles within Table 1 could be implemented.

It is suggested that the first principle (addressing specified problems) is enhanced by strengthening the process of educational needs assessment. This concept is drawn from the staff development literature (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1993) and from developmental theory, and it encourages the CBT supervisor to negotiate goals so that they better reflect the interests of other stakeholders (e.g. the relevant professional body; service users). To be concrete, the usual starting point in CBT supervision is collaborative agenda-setting (Liese and Beck, Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997), to generate topics reflecting the supervisees’ competencies, building on their strengths (Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996), and enabling them to operate in their learning zone (James, Milne, Blackburn and Armstrong, Reference James, Milne, Blackburn and Armstrong2007). The precision and fluency of this activity can be enhanced by utilizing a Learning Outcomes List. This list represents a menu of the possible in-session outcomes of CBT supervision, based on Kolb's (Reference Kolb1984) experiential learning model (see Milne, Reference Milne2007, for a copy). This represents an example of extending reflexive CBT supervision by adding an explicit “problem-solving cycle” aspect (see Table 1, principle 1), in the form of a list of options. This list also contributes to educational needs assessment, because the model has been endorsed within the BABCP (Lewis, Reference Lewis2005; i.e. it reflects the professional body's stake in supervision), and by experienced CBT supervisor trainers (Armstrong and Freeston, Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006).

The second principle in Table 1 includes the idea of extending reflexive CBT supervision beyond the usual focus on cognitions (especially cognitive case conceptualization: Padesky, Reference Padesky and Salkovskis1996; Liese and Beck, Reference Liese, Beck and Watkins1997), to encompass relevant behaviours and emotions (Pretorius, 2007). An example of how to process the emotional accompaniments to supervision effectively is to implement an “experiencing” phase. Within supervision, this entails increasing supervisees’ ability to focus on, accept and draw on their emotional reactions (e.g. to adapt to difficult circumstances). The Experiencing Scale (see Castonguay, Goldfried, Wiser, Rave and Hayes, Reference Castonguay, Goldfried, Wiser, Rave and Hayes1996) is a useful way to extend the supervision repertoire to facilitate supervisees experiencing. It sets out a continuum of emotional processing, starting with placing affective material on the agenda (e.g. anxiety about the supervisor's evaluation of a tape), progressing through heightened self-awareness to the exploration of the experience, then to meaning-making, and ideally concluding with an improved perspective and a greater capacity for problem-solving.

The third principle of CBT supervision, “goal-directed”, can be strengthened by incorporating developmental logic. This encourages CBT supervisors to attend to the developmental stage of their supervisees (see Stoltenberg, Reference Stoltenberg, Falender and Shafranske2008, for a major example of the developmental model in supervision), and to their own stage, particularly as this interacts with that of the supervisee. For example, a novice supervisee will initially tend to require concrete tasks and simple didactic methods, which may prove frustrating for the experienced supervisor.

The fourth principle (that CBT supervision is theoretically-driven) may be augmented by noting that there is a wealth of relevant material beyond clinical CBT theory. In particular, the findings and practices in the applied psychology of learning are especially compatible with CBT. General reviews can help to identify exciting developments in the science of learning, and promising options for enhanced practice. An example is The National Research Council's review (Bransford, Brown and Cocking, Reference Bransford, Brown and Cocking2000), which helpfully summarizes the research evidence and implications for practice in such areas as expertise, and the design of learning environments. Another, more directly applicable example can be found in the sphere of staff training (e.g. Colquitt, LePine and Noe, Reference Colquitt, LePine and Noe2000).

Due to space limitations, I will now treat jointly the fifth principle (that interventions are brief) and the sixth (that we aim to foster self-regulation), again using the psychology of learning as a resource. The example noted in Table 1 is to increase “challenge” in CBT supervision. This refers to supervisory activities, like Socratic questioning, that are intended to create doubt, perplexity and uncertainty in the supervisee (Zorga, Reference Zorga2002). There is good theoretical reason to believe that this is necessary for experiential learning (Kolb, Reference Kolb1984). A clear example of a supervisory dialogue that includes systematic questioning can be found in James, Milne and Morse (Reference James, Milne and Morse2008).

Principle seven concerns the importance of the supervisory relationship, the learning alliance, and there was no specific augmentation proposed in Table 1, though the fascinating and useful work of Safran on the cycle of “ruptures and repairs” is worth noting (see, for example, Safran, Muran, Stevens and Rothman, Reference Safran, Muran, Stevens, Rothman, Falender and Shafranske2008).

Principles eight and nine have been added to ensure that an augmented approach to CB supervision fully recognizes fundamental aspects of CBT, namely the environmental context and R&D. There is empirical work that suggests how particular supervision environments foster learning (Milne and James, Reference Milne and James2005), and hence CBT supervision can be augmented by attending closely to the relationship between supervisory micro-skills and the activation of the supervisees’ learning modes (i.e. reflection, conceptualization). Regarding the proximal and distal environment, the Newcastle Cake-stand model helpfully enumerates and discusses how related tiers provide a necessary contextualization of supervision (Armstrong and Freeston, Reference Armstrong, Freeston and Tarrier2006).

Finally, regarding R&D, I now return to my claim that specialized CBT supervision can improve fidelity. By drawing again on the applied psychology of learning (e.g. the literature on developing athletes, children, therapists and others: see Milne, James, Keegan and Dudley, Reference Milne, James, Keegan and Dudley2002), and on relevant CBT supervision research (e.g. Komaki and Citera, Reference Komaki and Citera1990), a manual for developing competence in CBT supervision has been designed and piloted (Milne, Reference Milne2007). Together with a new instrument for measuring competence in CBT supervision (Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2008), this affords an improved approach to ensuring that supervision is delivered with fidelity. The instrument (SAGE: Supervision: Adherence and Guidance Evaluation) can supplement this training, by providing corrective feedback. SAGE has promising inter-rater reliability (r = 0.82) and criterion validity (significant differences between reflexive and specialized CBT supervision: Cliffe, Reference Cliffe2008), so merits further attention.

Conclusions

The current approach to CBT supervision is commendably reflexive but insufficient, failing to recognize CBT supervision as a competence specialization, and has poor fidelity. We should augment the reflexive approach with an innovative, specialized approach (see Milne, Reference Milne2009, for a detailed account). This incorporates recent theoretical developments, commits to R&D, and results in a suitably distinctive, evidence-based approach. Future directions include developing a manual to guide the training of specialist CBT supervisors, extending our toolkit of instruments to match (e.g. to supplement SAGE with a suitable supervisee's scale), and treating supervision as a core part of the CBT enterprise.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.