Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is diagnosed when an adolescent experiences unexplained chronic and severe fatigue, lasting for at least 3 months; the fatigue does not remit with rest and causes significant interference in their functioning (NICE, 2007; RCPCH, 2004; Sharpe etal., Reference Sharpe, Archard, Banatvala, Borysiewicz, Clare, David and Lane1991). Additional symptoms may include nausea, dizziness, hypersensitivity to noise, light or touch, pain, post-exertional malaise and cognitive problems (NICE, 2007). Approximately 0.1–2% of adolescents are affected by CFS (Brigden etal., Reference Brigden, Loades, Abbott, Bond-Kendall and Crawley2017). Physically, adolescents with CFS can experience limitations in their ability to perform daily activities, such as walking short distances and climbing the stairs (Garralda and Rangel, Reference Garralda and Rangel2004). Beyond the physical impact, the impact of CFS on school functioning is also substantial; adolescents presenting to specialist services attend an average of 40% of school, miss an average of 1 year of school, and struggle to return to full-time education (Bould etal., Reference Bould, Collin, Lewis, Rimes and Crawley2013; Crawley and Sterne, Reference Crawley and Sterne2009; Sankey etal., Reference Sankey, Hill, Brown, Quinn and Fletcher2006). Their symptoms also prevent them from fully engaging in social relationships with their peers. The resulting lack of social life and of academic achievement impact on identity and contribute to a sense of failure for the adolescent (Parslow etal., Reference Parslow, Harris, Broughton, Alattas, Crawley, Haywood and Shaw2017).

Given the significant impact that CFS has on physical, academic and social functioning, one of the main aims of treatment is to improve functioning. Therefore, patient-reported outcome measures frequently include assessments of functioning. It is important to ensure that the measures that are commonly used for these purposes are valid and reliable.

Physical functioning captures activities of daily living such as walking and getting dressed (Tomey and Sowers, Reference Tomey and Sowers2009). In paediatric CFS samples, physical functioning is often assessed using the 10 physical functioning items of the well-validated health survey, the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire (Crawley and Sterne, Reference Crawley and Sterne2009; May etal., Reference May, Emond and Crawley2010). Using this measure, 98% of young people with CFS presenting to specialist services reported being limited to some degree in activities of daily living and/or mobility (Crawley and Sterne, Reference Crawley and Sterne2009). Worse physical functioning was also associated with other unfavourable outcomes, including increased fatigue, pain and mood (Crawley and Sterne, Reference Crawley and Sterne2009). The Physical Functioning Subscale has also been used as an outcome measure in treatment trials in paediatric CFS (Brigden etal., Reference Brigden, Beasant, Hollingworth, Metcalfe, Gaunt, Mills and Crawley2016; Chalder etal., Reference Chalder, Deary, Husain and Walwyn2010; Crawley etal., Reference Crawley, Gaunt, Garfield, Hollingworth, Sterne, Beasant and Montgomery2017; Lloyd etal., Reference Lloyd, Chalder and Rimes2012a). Despite its extensive use, detailed psychometric analysis has not previously been published.

School functioning can be thought of as multi-dimensional, encompassing not only academic achievement, but also social skills development, peer interactions and relationships, and extracurricular activities. A recent review highlighted the lack of validated questionnaires for assessing the school and social functioning of adolescents with CFS (Tollit etal., Reference Tollit, Politis and Knight2018). The proxy for school functioning that is most commonly assessed as an outcome measure is school attendance (Chalder etal., Reference Chalder, Deary, Husain and Walwyn2010; Crawley and Sterne, Reference Crawley and Sterne2009; Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Chalder and Rimes2012a). This is an important but unsubtle measure that does not fully capture the extent to which symptoms like cognitive difficulties impair functioning and engagement within the school environment. Neither does it capture the social impact of the illness (Tollit et al., Reference Tollit, Politis and Knight2018).

In adults of working age with CFS, the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt etal., Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist2002) has been used extensively in research, including as an outcome measure in randomised controlled trials (Burgess etal., Reference Burgess, Andiappan and Chalder2012; Deale etal., Reference Deale, Chalder, Marks and Wessely1997; Quarmby et al., Reference Quarmby, Rimes, Deale, Wessely and Chalder2007; White etal., Reference White, Goldsmith, Johnson, Potts, Walwyn, DeCesare and Cox2011). The WSAS is a brief self-report measure assessing functioning in work, domestic, social and leisure activities and close relationships. It has been found to be reliable and valid in an adult group of patients with CFS (Cella etal., Reference Cella, Sharpe and Chalder2011) and is appealing for use with adolescents who are fatigued due to its brevity and relative simplicity. The adapted version, designed for adolescents, has been used as an outcome measure in a treatment trial (Lloyd etal., Reference Lloyd, Chalder, Sallis and Rimes2012b), but detailed psychometric analysis has not previously been published.

CFS impacts significantly on adolescents’ physical, school and social functioning. Therefore, these aspects of disability associated with the illness are important to measure during clinical assessments and as an outcome measure following treatment. This study aimed to establish the psychometric properties and factor structure of (a) a commonly used physical functioning measure, the Physical Functioning Subscale of the SF-36, and (b) an adapted version of the WSAS, the School and Social Adjustment Scale (SSAS), a measure of school and social functioning, in adolescents with CFS.

Method

Participants

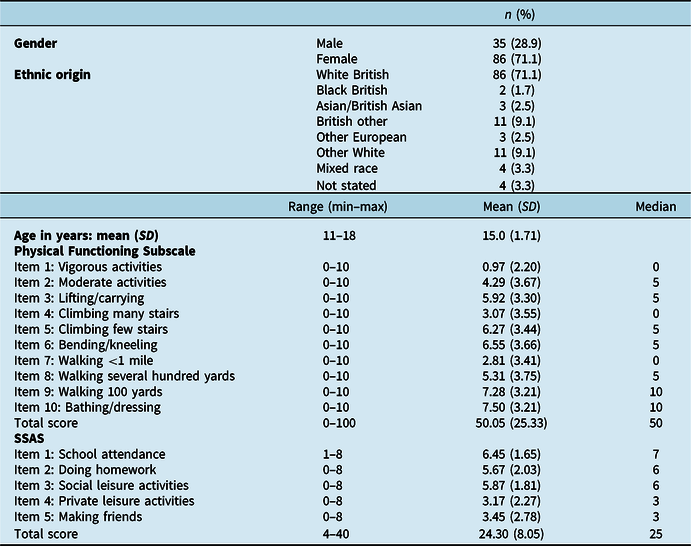

The data for this study were collected as part of a larger study. The inclusion criteria were adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of CFS (NICE, 2007), attending an initial assessment at one of two specialist CFS units in London. All eligible consecutively referred patients who attended an initial clinical assessment appointment at the units were invited to participate. Data collection at the main study site, where 91% of the participants were recruited, commenced in August 2010 and continued until October 2017. Eleven participants were recruited at a second site between August 2010 and January 2012. Across both sites combined, 207 adolescents attended for an assessment, 135 of whom met the eligibility criteria. One hundred and twenty-one (89.6%) participated in the study (see Table 1 for participant demographics).

Table 1. Participant demographics and scores on Physical Functioning Subscale and SSAS

Our sample size of 135 is not as large as one often uses in latent trait models, yet it yields 13.5 to 1 and 27 to 1 participant/item ratios. These ratios are higher than the common rule of thumb on the field (8–10 to 1 ratio or less; see Cattell, Reference Cattell1978). In addition, the simplicity of the potential sample structure expected due to the small number of items (1- or 2-factor models), allows for the method to work adequately [see de Winter etal. (Reference de Winter, Dodou and Wieringa2009) for a simulation study on sample size for factor analysis].

Measures

Participants were asked to provide information on important demographics.

Physical functioning

The Short Form-36 Physical Functioning Subscale (McHorney etal., Reference McHorney, Ware and Raczek1993; Ware and Sherbourne, Reference Ware and Sherbourne1992), referred to here as the Physical Functioning Subscale, is made up of 10 items, describing various activities of daily living (see Table 2). Items are rated on a 3-point scale and responses indicate the extent to which the respondent thinks that they are limited by their health in each activity. Items were coded as 0 (yes, limited a lot), 5 (yes, limited a little) and 10 (no, not limited at all). Thus, higher scores indicate better functioning, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 100.

Table 2. Items included in SSAS and Physical Functioning Subscale measures and reliability indices at item level

AID, α if item deleted; ITC, item-total correlation; SSAS, School and Social Adjustment Scale.

School and social functioning

The School and Social Adjustment Scale (SSAS) is an adapted version of the WSAS, which was designed for use in adults of working age (Cella etal., Reference Cella, Sharpe and Chalder2011; Mundt etal., Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist2002; Thandi etal., Reference Thandi, Fear and Chalder2017). It is composed of five items corresponding to work, domestic, social and leisure activities and close relationships in adults, each of which the respondent is asked to rate on a 0–8 scale. Higher scores are indicative of greater impairment in functioning, with a total possible score of 0–40. For use in adolescents, the word ‘work’ in the first item of the WSAS was replaced by the words ‘school/college’, and the scale was therefore called the ‘School and Social Adjustment Scale’ (see Table 2).

Fatigue

The Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ; Chalder etal., Reference Chalder, Berelowitz, Pawlikowska, Watts, Wessely, Wright and Wallace1993) is an 11-item scale that measures the severity of physical and cognitive fatigue. Items are rated on 4-point scales with reference to the past month. Higher scores indicate more severe fatigue. In the current study, Cronbachʼs alpha was .89 for the total score.

School attendance

Adolescents were asked to report how many full days and half days they attended school in an average week and this was converted into a percentage. This way of assessing school attendance has previously been used in paediatric CFS samples (Chalder etal., Reference Chalder, Deary, Husain and Walwyn2010; Crawley and Sterne, Reference Crawley and Sterne2009; Lloyd etal., Reference Lloyd, Chalder and Rimes2012a; Stulemeijer etal., Reference Stulemeijer, de Jong, Fiselier, Hoogveld and Bleijenberg2005).

Sit-to-stand test (SST)

The SST is an objective test of physical functioning which encompasses functional strength, endurance and exercise capacity. The participant is instructed to perform five consecutive sit-to-stand manoeuvres, starting from a seated position in a chair, as quickly as possible (Csuka and McCarty, Reference Csuka and McCarty1985). The speed of completion is used as a measure of physical strength. This test has good reliability and validity (Bohannon, Reference Bohannon2011). SSTs have previously been used as an outcome measure in adolescents with CFS (Gordon etal., Reference Gordon, Knapman and Lubitz2010).

Procedure

During the patients’ first assessment, the assessing healthcare professional discussed the study and shared a participant information sheet. Patients had the opportunity to discuss the study in more detail with a research assistant after the clinical assessment. Subsequently, both adolescent patients and their parents provided written consent to participate in the study. Participants completed a questionnaire pack which was returned to the study team. During the initial phase of the study (2010–2012), participants were also invited to complete a series of laboratory tasks, including the SST.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, 2017) and Mplus 8.4 (Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998). All available data were used in the analyses using a listwise approach, as the number of missing values was very low (less than 7%, i.e. four individuals with incomplete data on the Physical Functioning Subscale and eight individuals with incomplete data on the SSAS). Imputation for missing data was considered unnecessary.

As no a priori expectations or theoretical guidelines exist on the dimensionality of the scales, we used exploratory factor analysis, rather than confirmatory factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis for categorical data (often referred to as item factor analysis) via the weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV; Muthén etal., Reference Muthén, du Toit and Spisic1997); rotation (Promax) was employed to investigate the dimensionality of the ten items of the Physical Functioning Subscale, when used as a stand-alone scale. This approach was followed as the items were rated on a 3-point ordinal scale. On the contrary, the common factor model was used for the five SSAS metrical items. The maximum likelihood method was employed, to account for the missing values. All latent variable models analysis was conducted in Mplus.

The model fit was evaluated using measures of absolute and relative fit. Specifically, we report on the relative chi-square (rel χ2: values close to 2 indicate close fit; Hoelter, Reference Hoelter1983), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, values less than 0.8 are required for adequate fit; Browne and Cudeck, Reference Browne and Cudeck1993), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI, values higher than 0.9 are required for close fit; Bentler & Bonett, Reference Bentler and Bonett1980) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI, values higher than 0.9 are required for close fit;).

To investigate internal consistency, Cronbachʼs alpha (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951), alpha if item deleted, and item-total correlations were computed within each factor. Problematic items, in terms of reliability, were defined. The item-total correlations would be larger than 0.8 (redundant items) or below 0.3 (non-consistent items), and/or items that increased the reliability of omitted from the scale, indicated by alpha if item omitted.

Correlations between the SSAS total score, the Physical Functioning Subscale, and self-rated percentage school attendance and the SST were examined to investigate the concurrent, construct (discriminative and convergent) validity.

Results

Factor analysis and reliability

For the Physical Functioning Subscale (10 items), one eigenvalue above 1 emerged (7.1, with the second one being 0.8), suggesting 1-factor structure according to Kaiserʼs criterion (also see the corresponding scree plot; Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material). The 1-factor model provided adequate but not close fit to the data (rel χ2 = 2.3; RMSEA = 0.107, p-close = 0.002; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.98). According to the chi-square test for nested models, increasing the number of factors to two significantly improved the fit in our data (χ2 = 34.714, d.f. = 9, p < 0.001). Indeed the 2-factor model emerged a close fit to our data (rel χ2 = 1.7; RMSEA = 0.080, p-close = 0.110; TLI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99). The factor structure is presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Factor structure for Physical Functioning Subscale

Cronbachʼs α coefficient for the 10-item Physical Functioning Subscale was .91. As the exploratory analysis suggested two subscales, internal consistency was estimated within each. For the first factor (items 1, 2, 3, 4 and 10) alpha was .82, and for the second factor (items 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) alpha was .89, suggesting satisfactory reliability for both factors.

For the SSAS 5-item scale, one eigenvalue above 1 was present (2.97, with the next one being 0.82; see also the scree plot Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Material). The 1-factor model provided adequate but not close fit to the data (rel χ2 = 5.1; RMSEA = 0.184, p-close = 0.001; TLI = 0.81; CFI = 0.91). According to the chi-square test, by increasing the number of factors to two, the fit was not significantly improved, therefore the 2-factor solution was not appropriate for this scale (χ2 = 0.210, d.f. = 1, p = 0.647). Cronbachʼs α coefficient for the 5-item SSAS was .81.

The inter-item correlations within each subscale ranged from 0.22 to 0.71 on the Physical Functioning Subscale and 0.30 to 0.63 on the SSAS. Using alpha if item deleted and item-total correlations, we did not identify any problematic items on either scale (Table 2).

Convergent and divergent validity

Convergent validity is demonstrated by the strength of the relationship between scores from different measurements. We assessed convergent validity by utilising different measures of impairment. Specifically, we expected that the Physical Functioning Scale would be moderately correlated with self-reported percentage school attendance and the more objective SST as they assess similar constructs. We also expected that the SSAS-total and the SSAS school-related items (school attendance and doing homework) would be moderately correlated with percentage school attendance. The correlations were in the expected direction (Table 4).

Table 4. Pearsonʼs correlation coefficient [r (p)] between Physical Functioning Subscale, SSAS scores and selected measures

SSAS, School and Social Adjustment scale; SST, sit-to-stand test (time taken). Higher scores on Physical Functioning Scale indicate better functioning; higher scores on SSAS indicate greater impairment in functioning.

There was evidence of divergent validity with SST having small correlations with SSAS. There were also smaller correlations between the SSAS making friends and leisure activities items and percentage school attendance than there were between percentage school attendance and the school-related items of the SSAS (school attendance, doing homework), providing further evidence of divergent validity.

Discussion

Given the significant impact that CFS has on functioning for affected adolescents, it is important to establish whether the commonly used measures of physical, school and social functioning are valid and reliable. We found that the Physical Functioning Subscale as a measure of physical functioning appeared to be reliable and valid, although it appeared to separate into two factors rather than representing a single construct. The SSAS, a measure of school and social functioning, was also found to be reliable and valid. The fits for 1- and 2-factor solutions were adequate but not close, suggesting that it might be tapping multiple factors.

Factor structure

On the Physical Functioning Subscale, the items that clustered together in the factor analysis were (a) vigorous activities, moderate activities, lifting and carrying, climbing many stairs, and bathing/dressing, and (b) climbing few stairs, bending and kneeling, and walking any distance. However, as there were several items with substantial cross-loadings (e.g. PF4, PF10, PF5), this method of scoring is suggested tentatively., We attempted to use different rotation methods but the cross-loadings were persistent. A one-dimension solution was not acceptable in our data, so it does appear that in adolescents, there are two separable dimensions of physical functioning. Based on our factor analysis, the first subscale may capture more physically demanding tasks, but also tasks that are easier to relinquish or modify. The second subscale appears to encompass basic activities of daily living that adolescents must engage in in their day-to-day lives. The items on the Physical Functioning Subscale could be divided into two 5-item subscales with items 1–4, and item 10 forming one subscale, called ‘Physically demanding activities’, and items 5–9 forming another subscale, called ‘Basic physical activities’. Using the widely accepted coding method of 0 (yes, limited a lot), 5 (yes, limited a little) and 10 (no, not limited at all), each 5-item subscale would have a possible total score ranging from 0 (extremely impaired) to 50 (not impaired at all).

The SSAS is a potentially helpful assessment and outcome measure, which focuses on participation in life, encompassing a broader range of functioning than the more typically used percentage of school attendance. In adults, the WSAS, from which the SSAS was developed, a distinct social functioning factor has been found (i.e. a 2-factor solution) (Zahra etal., Reference Zahra, Qureshi, Henley, Taylor, Quinn, Pooler and Byng2014), but this did not appear to be the case for adolescents with CFS in the current study. This may be because social life and school are inherently interconnected for adolescents. In adults they can be separated more easily. For example, an adult may reduce their social participation by curtailing their social activities substantially to accommodate feelings of fatigue, whilst continuing to work.

Convergent and divergent validity

We have provided some preliminary evidence of convergent validity. Physical functioning and school and social functioning were moderately associated with one another, and with time taken to complete a sit-to-stand test, which is an objective measure of physical functioning. This provides evidence of construct validity as we would theoretically expect these measures, all of which encompass functioning, to be related.

There was evidence of divergent validity as there were relatively small correlations between functioning and self-reported percentage school attendance. Being present at school (or not) is unlikely to capture the multi-dimensional nature of school functioning which includes academic achievement, social relationships and extracurricular activities. Our argument for utilising the SSAS as a measure in this population was that school attendance as an index of participation and functioning in that environment is not sufficiently nuanced to capture the extent to which CFS hampers academic and social functioning, for instance, through poor concentration.

Limitations

The sample was recruited consecutively from all eligible participants who attended the CFS units during the recruitment periods, which is likely to have limited selection bias. However, we do not know whether the findings apply to those who do not attend specialist services (for example, those who are managed in primary care settings). Furthermore, we assumed homogeneity across the two recruitment sites, but were not able to control for collection site in our analyses, which may have led to biases. Given the small number of participants recruited from the second site, this is unlikely. The Physical Functioning Subscale is a subscale of a larger (36-item) scale, and only this subscale was used in the current study. Although the brevity of the school and social functioning measure is appealing, it could be argued that it still does not cover all the facets of school and social functioning, as it may, for example, neglect concentration and attention within the classroom environment. In this study, we have relied primarily on self-report scales, although a strength is the inclusion of the SST as an objective measure of functioning.

The current study explored some of the psychometric properties of these measures, but further research is required to assess test–re-test reliability, group differences and treatment sensitivity. In the current study, a second sample that could potentially be used to confirm the factor structure via confirmatory factor analysis, was not available.

Conclusions

CFS is a debilitating illness, which affects functioning across multiple domains, including school and social functioning, and physical functioning. In adolescence, this interferes with school attendance and performance. Having brief, reliable and valid measures of functioning in these domains is important to inform assessment and management of CFS-related disability in school students.

Measures are often used with adolescents that have been developed for adults. However, due to the developmental and contextual differences of young people, these may need to be adapted or interpreted differently in this specific population. We found some evidence of reliability and validity of the two measures we tested. We also found that the physical functioning scale may be better conceptualised as two factors, basic physical activities, and physically demanding activities. The SSAS may encompass several aspects of functioning, although the fit as a single construct was acceptable. As physical, school and social functioning are important aspects of health to assess in adolescents with CFS, we have shown that these measures provide a way to do this, although further psychometric investigation is warranted. As these measures were developed for adults, a preferable approach with better face validity may be developing measures specifically for adolescents.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000193

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kate Lievesley who contributed to the design and data collection for this project, and all the young people and their families who took part in this study.

Financial support

M.L. receives salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship Scheme. T.C. and S.V. acknowledge the financial support of the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health award to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and the Institute of Psychiatry at Kingʼs College London. This paper represents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Kingʼs College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of interest

T.C. is the author of several self-help books on chronic fatigue for which she has received royalties. T.C./KCL have received ad hoc payments for workshops carried out in long-term conditions. KCL have received payments for T.C.ʼs editor role in the Journal of Mental Health. K.R. has co-authored a book with T.C. called Overcoming Chronic Fatigue in Young People, for which she receives royalties. M.L. and S.V. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statements

Approval was granted by NHS research ethics committee (LREC, reference no. 08/H0807/107), and by the Research and Development departments at the South London and Maudsley (SLaM) NHS Trust, and Great Ormond Street Hospital. Approval for the collection of routine outcome measures was also given by the clinical audit committee of Psychological Medicine Clinical academic group of SLaM.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.