Introduction

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a behavioural therapy based on Relational Frame Theory (RFT). The main tenet of RFT is that verbally-mediated private events do not directly influence behaviour but do so through the context in which they occur. Unlike traditional behaviour therapies, ACT attempts to modify the relationship with negative private events (such as thoughts and feelings) rather than the content of such thoughts or presence of feelings (Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson, Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999). ACT claims that relationships with negative private events, characterized by avoidance and suppression, increase the frequency and functional importance of the thoughts and feelings that are being avoided. Based on ACT principles, this struggle with unwanted private events is thought to cause psychological distress and underpin psychopathology (Hayes, Masuda and De Mey, Reference Hayes, Masuda and De Mey2003). The therapeutic approach of ACT is to change the function of negative thoughts and feelings by changing responses to these private experiences. This is achieved by learning to let go of attempts to control and avoid unwanted private events, focusing on the present, clarifying values and making a commitment of action consistent with those values (Hayes, Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2004; Pankey and Hayes, Reference Pankey and Hayes2003).

ACT proposes that these changes are effected through six theoretically defined processes (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999; Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2012; Hayes, Villatte, Levin and Hildebrandt, Reference Hayes, Villatte, Levin and Hildebrandt2011). “Acceptance” is the willingness to experience private events with an attitude of curiosity, disengage from attempts to change their frequency or form, and make room for their occurrence. “Defusion” aims to change the way one relates to or interacts with thoughts and unwanted private events. Defusion targets the entanglement with unwanted private events (e.g. thoughts are literal reality) by changing the function, rather than the content or frequency. These experiences come to be viewed as just mental activity, reducing the impact on behavioural responses. Employing attentional control, “contact with the present moment” promotes attending to environmental and psychological events as they occur, in the here-and-now. This direct experience with the world reduces the influence of past and future experiences that may affect behaviour, allowing more flexible behaviours that are consistent with values. “Self as context” is the ability to consider oneself as a matter of consistent perspective, experiencing a variety of emotions, thoughts, behaviours and experiences. This allows private experiences to be considered as distinct from self and, as such, have less impact and perceived as less threatening. Acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment, and self as context are employed to work towards living a more meaningful, values consistent life. In ACT, “values” work aims to clarify values, defined as freely chosen beliefs that are intrinsically reinforcing, rather than goals, which are objective and obtainable. “Committed action” aims to encourage behaviour in accordance with these values, despite the presence of symptoms or other internal events. This behaviour change is likely to result in psychological barriers, which are addressed through the ACT processes (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999; Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis, Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl, Wilson, Bissett, Pistorello and Toarmino2012).

While all ACT processes are related, each is interlinked with one process more than others. Acceptance and defusion both aim to undermine the person's literal relationship with language (e.g. unwanted thoughts or voices) and support openness to direct experience. Self as context and contact with the present moment involve reduced attachment to one's self-story (conceptualized self) and greater contact with the here and now. Values and committed action involve choosing to act in accordance with one's values. These relationships have recently been described as 3-process response styles, Open (acceptance-defusion), Centred (contact with the present moment-self as context) and Engaged (values-committed action). These response styles work together to contribute to psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl, Wilson, Bissett, Pistorello and Toarmino2012). Psychological flexibility is defined as the ability to contact the present moment and change or persist in behaviour consistent with values, which is thought to improve psychological functioning (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl, Wilson, Bissett, Pistorello and Toarmino2012; Hayes, Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2004; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999).

ACT has been applied to a range of clinical conditions (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Masuda and De Mey2006) including substance use, chronic pain, depression, diabetes management, and social phobia (Block and Wulfert, Reference Block and Wulfert2000; Gregg, Glenn, Callaghan, Hayes and Glenn-Lawson, Reference Gregg, Callaghan, Glenn, Hayes and Glenn-Lawson2007; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Villatte, Levin and Hildebrandt2004; Dahl, Wilson and Nilsson, Reference Dahl, Wilson and Nilsson2009; Zettle and Raines, Reference Zettle and Raines1989) and, more recently, psychosis (Bach and Hayes, Reference Bach and Hayes2002; Gaudiano and Herbert, Reference Gaudiano and Herbert2006a). For people diagnosed with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, CBT has clear evidence for efficacy (Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier, Reference Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier2008) and is the psychological treatment recommended as an adjunct to antipsychotic treatment by current clinical practice guidelines (NICE, 2010; Kreyenbuhl, Buchanan, Dickerson and Dixon, Reference Kreyenbuhl, Buchanan, Dickerson and Dixon2010). However, despite its success, 30–50% do not significantly benefit from CBT (Emmelkamp, Reference Emmelkamp and Lambert2004; Garety, Fowler and Kuipers, Reference Garety, Fowler and Kuipers2000), suggesting a need for alternative approaches. Evidence is now accumulating that ACT may be beneficially applied to psychosis. Two randomized controlled trials of brief ACT interventions for in-patients with positive symptoms of psychosis found 50% fewer rehospitalizations compared with controls, and improvement in social functioning (Gaudiano and Herbert, Reference Gaudiano and Herbert2006a). A reduction in believability of unwanted thoughts was found to mediate the impact of treatment (Bach and Hayes, Reference Bach and Hayes2002). A pilot trial focusing on emotional recovery of outpatients (rather than persisting symptoms) following an acute psychotic episode showed improvements in negative symptoms of psychosis and depression, and reduced crisis contacts (White et al., Reference White, Gumley, McTaggart, Rattrie, McConville and Cleare2011). A more recent study evaluated the efficacy of an Acceptance-based CBT intervention for command hallucinations, “Treatment of Resistant Command Hallucinations” (TORCH), compared to Befriending (control intervention) (Shawyer et al., Reference Shawyer, Farhall, Mackinnon, Trauer, Sims and Ratcliff2012). This RCT was underpowered and showed no between-group differences on variables of interest. However, the combined therapy groups showed greater benefits when compared with the waiting list group on half of the outcome measures, suggesting that both therapies may have been effective. Within group comparisons showed significant but largely different effects for both TORCH and Befriending, with TORCH showing benefits on a wider range of outcomes. The results suggest TORCH and Befriending work in different ways. The TORCH group had significant improvements in general auditory hallucinations, in illness severity, global functioning, and quality of life, whereas the Befriending group experienced significant improvements in command hallucinations and distress. Interestingly, no differences were found in process (acceptance) measures. Patients reported benefit from both therapies, although TORCH was rated as significantly more beneficial (Shawyer et al., Reference Bach and Hayes2012). Whilst showing promise, further research is necessary to clarify the efficacy of ACT for psychosis. A current RCT is investigating the efficacy of ACT for people with medication-resistant positive psychotic symptoms (Farhall, Shawyer and Thomas, Reference Farhall, Shawyer and Thomas2010). The current study comprises one component of this research program.

Meta analyses have established the overall effectiveness of ACT (Öst, Reference Öst2008; Powers, Zum Vorde Sive Vording and Emmelkamp, Reference Powers, Zum Vörde Sive Vörding and Emmelkamp2009); however, the methodological limitations of ACT research have been the subject of criticism. These include reliability and validity of outcome measures, checks for treatment adherence, and reliability of diagnosis, amongst others, when comparing ACT with matched CBT RCTs (Öst, Reference Öst2008). Gaudiano (Reference Gaudiano2009) argues it is inappropriate to match studies of the established treatment of CBT with a relatively young ACT research base. Current debate in the literature emphasizes the need for ongoing research into the ACT model. The processes of change and the effectiveness of therapy components have also been the focus of considerable research (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Masuda and De Mey2006). Process analyses have linked ACT components (acceptance and defusion) and psychological flexibility with increasing acceptance related behaviour and outcome in problems such as anxiety, pain tolerance, and tinnitus distress (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Masuda and De Mey2006; Hayes, Orsillo and Roemer, Reference Hayes, Orsillo and Roemer2009; Hesser, Westin, Hayes and Andersson, Reference Hesser, Westin, Hayes and Andersson2009; McCracken and Gutérrez-Martínez, Reference McCracken and Gutérrez-Martínez2011); however, the small number of psychosis studies have limited the investigation of processes for that population.

The measurement of ACT construct variables presents a challenge in ACT process research. The dominant measure, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ) was designed to measure experiential avoidance. Within the ACT model, experiential avoidance and acceptance has been defined more broadly as psychological flexibility. The revised AAQ (i.e. AAQ-II) measures the same construct with improved psychometric properties and appears to be measuring a single construct of psychological flexibility (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Hayes, Baer, Carpenter, Guenole and Orcutt2011). It would be interesting to understand which processes are more or less active in contributing to psychological flexibility.

A recent emphasis on values processes is encouraging, with values having a mediating role in ACT, suggesting, at least, clarification of values contributes to change. Values-based action has typically been measured using the AAQ (with values-based action one factor that loads on to psychological flexibility as a second order factor) (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Masuda and De Mey2006). However, the AAQ seems to be more related to committed action (e.g. “My thoughts and feelings do not get in the way of how I want to live my life” (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Hayes, Baer, Carpenter, Guenole and Orcutt2011). Specific values questionnaires have also been used, although these often consist of predetermined values (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2009; Vowels, McCracken and Eccleston, Reference Vowles, McCracken and Eccleston2008). This restriction may result in endorsement of domains due to social desirability rather than relevance and importance.

Mindfulness promotes non-judgemental “contact with the present moment” and attention control, and in one form or other is central in other therapies (e.g. MBCT, MBSR, DBT) (Milton and Ma, 2011). Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility and value of development of mindfulness skills for people living with psychosis (Abba, Chadwick and Stevenson, Reference Abba, Chadwick and Stevenson2008; Chadwick, Hughes, Russell, Russell and Dagnan, Reference Chadwick, Hughes, Russell, Russell and Dagnan2009), including through an ACTp individual therapy (White et al., Reference White, Gumley, McTaggart, Rattrie, McConville and Cleare2011). In the context of ACT, mindfulness facilitates many processes including acceptance, defusion, self as context, and contact with the present moment (Fletcher and Hayes, Reference Fletcher and Hayes2005; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Masuda and De Mey2006). Only one study has investigated mindfulness as a component in ACTp: White et al. (Reference White, Gumley, McTaggart, Rattrie, McConville and Cleare2011) reported mindfulness was correlated with a decrease in post-therapy depression scores following psychosis.

Believability as a proxy for defusion has been used in research for some time, with a reduction in believability mediating treatment effects (Zettle and Hayes, Reference Zettle and Hayes1986; Hayes, et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006; Zettle, Rains and Hayes, Reference Zettle, Rains and Hayes2011). Believability as a measure of defusion has also been used in psychosis. A formal mediation study (Gaudiano, Herbert and Hayes, Reference Gaudiano, Herbert and Hayes2010) confirmed earlier findings (Bach and Hayes, Reference Bach and Hayes2002; Gaudiano and Herbert, Reference Gaudiano and Herbert2006b) that believability of hallucinations mediated the impact of therapy, in reducing hallucination related distress. Acceptance and defusion techniques provide a means to reduce preoccupation and distress associated with symptoms of psychosis (McLeod, Reference McLeod, Blackledge, Ciarrochi and Deane2008) and may be important in reducing believability of hallucinations in psychosis and improving behavioural change. However, there is some uncertainty about the validity of believability as a measure of defusion of psychotic experiences. Researchers suggest believability may be tapping into insight i.e. whether the psychotic experience is perceived to be self or other generated, rather than the believability of internally experienced thoughts and beliefs (Farhall, Shawyer, Thomas and Morris, in press). Farhall et al. (in press) suggest that asking about the truth of externally attributed psychotic symptoms may not indicate flexibility in thinking but insight, and suggest development of a measure of believability of the internally experienced thoughts and beliefs and the appraisal associated with positive psychotic symptoms. Alternatively, hallucinations and delusions could be considered an example of complete fusion, where any awareness of one's own thinking is lost. In this case, believability could be considered a measure of fusion, with current measures of conviction of beliefs available. Given the nature of the private events in psychosis (hallucinations and delusions) the measurement of ACT processes requires further clarification, particularly for this population.

Aims

Research in other therapies has demonstrated that systematic reporting of clients’ experience of therapy can provide a greater understanding of therapy processes and applications to particular populations, potentially leading to the further refinement of therapy (Elliott, Reference Elliott2010). Qualitative client interviews have been successful in investigating components of therapy (Allen, Bromley, Kuyken and Sonnenberg, Reference Allen, Bromley, Kuyken and Sonnenberg2009; Messari and Hallam, Reference Messari and Hallam2003; Dilks, Tasker and Wren, Reference Dilks, Tasker and Wren2008; McGowan, Lavender and Garety, Reference McGowan, Lavender and Garety2005) and thematic analysis provides for identification, analysis and reporting on themes within the data (King and Horrocks, Reference King and Horrocks2010). As yet little research has investigated ACT for psychosis (ACTp) from a client perspective. Therefore this study investigated ACTp participants’ perspectives of this therapy so as to gain a better understanding of how the six ACT processes are appraised and understood in the context of psychosis and to seek implications for theory and practice. The specific aims of this study were:

-

1. To describe how ACTp participants view and understand the therapy and its six core processes;

-

2. To identify ACT processes that participants consider helpful components of their therapy;

-

3. To identify any non-specific therapy factors that participants viewed as helpful components of their therapy.

Method

A qualitative research design is well suited to the exploration of participants’ perspectives and understandings of therapy, and a thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was chosen for this study.

Study context

Participants

This qualitative study was embedded in a RCT (known as Lifengage) evaluating the efficacy of ACT for chronic distressing psychosis (Farhall et al., Reference Farhall, Shawyer and Thomas2010). Eligible participants for the Lifengage RCT were outpatients aged 16–65 years, with a current diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, who experienced current residual hallucinations or delusions associated with significant distress or disability and whose symptoms had been present over the past 6 months with no change in antipsychotic medication type in the 8 weeks prior to intake. Exclusion criteria included a neurological disorder that may affect cognitive function, insufficient conversational English, an IQ less than 70, or currently receiving another form of psychological treatment.

Therapists

Therapy was provided by four clinical psychologists each with over 10 years’ experience in providing psychological treatment to people with psychosis. Therapists were trained in ACT and received ongoing supervision with one of the founders of ACT (Steven Hayes).

Therapy

Ninety-six participants were randomly assigned to either ACTp (Bach and Hayes, Reference Bach and Hayes2002; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999) or Befriending treatment conditions, and data collection is continuing. Befriending is a fully manualized active control intervention and focuses on neutral topics of interests for the client and avoids discussions of symptoms or problems (Bendall, Killackey, Jackson and Gleeson, Reference Bendall, Killackey, Jackson and Gleeson2003). ACT participants received eight 50-minute sessions of therapy delivered at weekly or fortnightly intervals within 4 months. An ACTp treatment guide was developed utilizing adaptations for psychosis recommended in the literature (Bach and Hayes, Reference Bach and Hayes2002) and relevant sections of the TORCH manual (Farhall et al., Reference Farhall, Shawyer and Thomas2010). Some of its therapy recommendations include: flexible applications for the ordering of the modules and material, degree of emphasis placed on a given module, and use of metaphors and exercises. The target for therapy was symptoms (which are often the cause for avoidance) and, if appropriate, underlying issues. Often entrenched delusional beliefs with high levels of conviction result in reactance when threatened (Thomas, Morris, Shawyer and Farhall, in press). If delusions were entrenched a more generic ACT approach, with an emphasis on values work, was recommended. A focus on values is likely to be less threatening and avoids any increase in fusion with delusions (e.g. defending beliefs using language, increasing the strength of the relationship between language and delusional beliefs). Mindfulness, defusion and values work were explored where possible from session two with mindfulness recommended for each session. If participants were less engaged and motivated, a focus on values and goals was recommended.

Psychotic experiences are often associated with distraction and cognitive difficulties such as concentration, disorganization and understanding abstract concepts (Tandon, Nasrallah and Keshavan, Reference Tandon, Nasrallah and Keshavan2009). The ACTp manual recommends strategies to focus attention to the task, aid memory and contain distress. Shorter, more concrete metaphors were selected for the manual. Exercises were kept as physically active as possible and metaphors adapted to be personally relevant where possible. All participants were encouraged to listen to a recording of each session for homework, use an ACT journal to record what was useful and jot down questions to review next session, and were provided with a therapy manual and a mindfulness CD.

The qualitative study

The qualitative study was conducted in the final phase of the Lifengage RCT, and convenience sampling was used to recruit up to 10 participants with whom to explore the research question. As such, all participants of the Lifengage project who completed eight sessions of ACTp within a 6-month timeframe were invited, when they attended the post-therapy assessment, to participate in a further one-hour interview to “talk about any helpful aspects of therapy they had experienced”. The researcher (TB) then telephoned those participants interested in being interviewed and, if agreed, arranged the interview. Five women and four men, aged 24–49 years (m = 36 years) were recruited. The highest educational qualification (four participants) was year 11/12, and three participants achieved diploma level education, primary school (one participant) and year 10 or less (one participant). Six participants were unemployed and/or volunteering, two participants were employed part-time and one participant was studying part-time.

Materials and procedures

Interviews

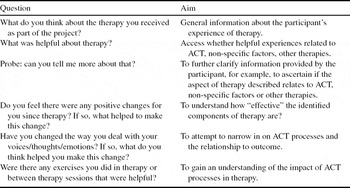

A semi-structured interview is recommended for gathering in-depth descriptive data (Hill and Lambert, Reference Hill, Lambert and Lambert2004), and thus was chosen for this study. The format allowed participants to reflect on their understanding of therapy without rigid boundaries, and interviewers to use probes, so that relevant information is collected (Hill and Lambert, Reference Hill, Lambert and Lambert2004). Interview questions were developed by the researcher (TB), drawing on literature about ACTp therapy processes, and then reviewed by the research supervisor from Lifengage project (JF), an experienced qualitative researcher (EF) and two service user consultants (with lived experience of psychotic disorders). Their suggested changes were made, a pilot interview was conducted, and interview questions further amended. Questions were initially open-ended, moving towards more closed questions if information was not spontaneously reported. Prompts and probes were used to clarify and elicit necessary information; examples are set out in Appendix A. Semi-structured interviews with participants were conducted within 3 weeks following ACTp completion. Interviews took place at the participant's usual place of treatment, were audio recorded and limited to approximately one hour. A fixed payment ($25) per interview was approved by the applicable ethics committees as in keeping with reimbursing participants for their time and minimizing the out-of-pocket expenses associated with participation. Whilst it is possible that knowledge that participation involved no out-of-pocket expense meant some ACTp clients viewed taking part more favourable, the payment was small and was provided at completion of the interview, so that it is unlikely to have unduly biased participants’ opinions.

Data analysis

Given that the research focused on exploration of both predetermined themes and in vivo themes, thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was used. Each interview was transcribed verbatim by the researcher. The transcripts were re-read several times (and notes made) to identify themes relating to participants’ understanding of ACTp, the usefulness of ACTp processes and therapy more broadly, those relating to other therapies (such as cognitive restructuring), as well as non-specific factors (such as feeling listened to by the therapist). Coding began with identifying the surface meanings within the data and data extracts were matched to them, rather than interpreting what a participant said. Data were coded based on the most basic segment of data (e.g. phrase, comment, intent) that “captures something important in relation to the overall research question” (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, p. 82). The codes were reviewed for compatibility with the raw interview information gathered in the interview, and grouped into themes (see Table 1 for an example). To theorize about any patterns in the data and their implications, the number and prevalence of categories were analysed.

Table 1. Example of theme development

Quality

A number of procedures recommended by Hill and Lambert (Reference Hill, Lambert and Lambert2004) were adopted to ensure the validity and reliability of the analysis. The primary researcher coded the data and queries were brought to regular review meetings attended by the co-authors with expertise in ACTp and qualitative research. Discrepancies were discussed and reviewed to ensure consistency and reduce researcher bias. The primary researcher (TB) transcribed the interviews to increase familiarity with data and continually referred back to the data at each stage of coding in thematic analysis. A reflexive journal was maintained throughout the research process, which included an audit trail to increase transparency of the process.

Results

Four main themes were identified, each with a set of sub-themes and further levels of description. These are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Table of themes and subthemes

Theme I: Usefulness of therapy

All participants reported that therapy was useful and generally recommended ACT, but for differing reasons. Five participants recommended mindfulness in particular. Two participants recommended ACTp predominantly for the benefits of feeling listened to, in addition to some specific ACTp components, but these two participants also held opposing views of the therapy overall, e.g. “. . . it was a bit useless as in the type of therapy” [P1] and reported difficulty understanding and connecting with it. Others held both positive and negative views. Another two participants also reported some “. . . experiences are too intense for ACT” [P3] and “mindfulness was not useful or exacerbated symptoms” [P4]. Some participants also highlighted perceived direct benefits of specific ACT processes. These are each described below.

Processes

Values

Five participations identified values as useful to give direction and meaning, making “. . . life a bit more fulfilled” [P5]. Three participants identified working on goals as useful to achieve specific outcomes such as improved relationships and housework, for example “. . . with the goal setting . . . that's helped me . . . I'm getting a better relationship with my family [P3]” and “. . . I had the goal of tidying the house and I did one room a day and that worked out . . .” [P4].

Mindfulness

Eight participants reported mindfulness helped to distract or redirect attention, for example, “If I'm hearing voices it will bring me back to focusing on what's real . . . it's really beneficial” [P6]. These participants also reported a reduction in distress and anxiety associated with voices, negative thoughts and paranoia, for example, “It helps me focus on something other than the voices so they don't become as distressing.” [P3]. All participants found mindfulness helped to calm and relax e.g. “It . . . eased my mind, made me more relaxed and got rid of all the stress and stuff” [P1]. However, for some experiences mindfulness was also described as less helpful – “If I'm deliberately listening to something it will exacerbate it” [P4] and “for less intense [experiences] it works good” [P3].

Defusion

Six participants reported defusion as useful, for example “Just the defusion technique was worth the 8 hours I spent there” [P5]. Defusion was identified by these participants as being useful with paranoia and reducing the impact and distress of negative thoughts and voices, for example, “. . . it's very helpful. . . the defusion techniques to get rid of the voices to make them less persistent. . . ease its impact . . .” [P5] and “. . . to try and look at my voices as a character . . . so they weren't as scary . . . so I can cope with it and also learning to not take what my voices say literally” [P8]. There were limitations to some defusion exercises where “defusion worked a bit too but not so much with the funny voices . . .’ [P4] as reported by three participants, two of whom identified the “story” strategy as most useful for intense experiences: “. . . when it comes to suicide for instance or . . . not so easy to make fun of [thoughts]. . . something like . . . ‘poor me story’ [helps]” [P5]. The “story strategy” is a defusion technique involving noticing familiar, repeated thoughts such as “I'm no good because . . .” as just another story the mind comes up with (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999). While three participants made no comment about defusion, three others found the “funny” voices technique useful. “Funny voices” refers to a defusion technique that involves repeating distressing thoughts in a variety of vocal tones, mimicking others’ voices, etc. This and the “story strategy” are exercises to reinforce the idea that, despite the emotions attached to them, thoughts are simply words (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999).

Acceptance

Two participants reported acceptance as useful, with a focus on letting go of the struggle. As described by one participant, a reduction in the intensity and distress associated with voices and no longer struggling with her symptoms and diagnosis resulted in less interference in her life, e.g. “that helped me in a way; it's like accepting what they say and just go whether I choose or not to actually do anything about it” [P9].

Theme II: Changes attributed to ACTp

Continue to act despite symptoms

All participants described continuing to experience symptoms. Six of the nine participants changed in their beliefs and attitude towards symptoms, for instance ACTp “. . . made me realize that I did not have to buy into messages and that I can . . . accept what's going on and move in the direction that I want to” [P4].

Change in perspective

Helpful changes in metacognitions were also described by six of nine participants as this quote illustrates “it sort of changes my perspective of the voices . . . [they're] not as intimidating as what they were” [P1] and “ACT actually helps you to see that you can't control your thoughts but you can control your behaviour and that's definitely a very important thing to learn” [P5].

Reduced intensity and impact of symptoms

Seven participants described changes in the way that symptoms were experienced, in particular changes in intensity, impact and distress. For example, “. . . now I've been doing the mindfulness I haven't been distressed” [P3], and “. . . I guess it's [paranoia] got a bit weaker . . . but I've got new ways of coping with it” [P4] and “Yes, they [voices] are still there but it's a better technique than actually getting angry with them” [P5].

Behavioural

All participants attributed to ACTp at least one positive behavioural change in their daily life, such as “I have been a lot cleaner with myself whereas before I wasn't caring, I wouldn't shave and stuff . . .” [P1], and greater motivation to make changes, for example, “. . . I'm going to have to totally change my way of life . . . I just want to start getting a lot more of a life happening . . . and I sort of believe that I can” [P4].

Theme III: Understanding of therapy

Some participants described difficultly engaging with therapy due to an apparent disconnect with therapy concepts and aims. Others believed they had a good understanding; however they noted potential difficulties understanding concepts.

Connection with therapy

Two participants explicitly reported therapy concepts and exercises were difficult such as “I found it more comical than useful . . . I didn't see the relevance” [P1] and “. . . I didn't know what she's on about” [P2].

Understanding therapy and exercises

There were multiple perspectives about the ease of understanding therapy. Two participants reported misunderstandings about therapy and exercises, for example: “. . . the whole objective of her methods and technique was just how to relax” and mindful walking as useful “. . . because I'm back in familiar surroundings I feel that my anxiety will go down as well” [P2]. Two participants noted “. . . if it had been over a longer period of time then it would have sunk in a bit more” [P4] and the benefit of written material. Others described therapy easy to understand, for example “[I] actually found it [therapy] quite easy” [P8].

Theme V: Non-specific therapy factors

All participants stated they found the therapist warm and professional and felt supported, understood and able to talk about their experiences. Four of the nine participants spontaneously identified how therapist factors were useful, notably that the therapist's non-judgemental stance helped to improve self-confidence, self-esteem and stress reduction, but no direct changes in symptoms. Participant seven said “. . . being myself with [therapist] helped me more being myself when I'm around other people . . . he's down to earth and doesn't judge people”.

Discussion

This study explored the active therapeutic processes of ACT and understanding of therapy as reported by individuals experiencing persistent symptoms of psychosis. Participants either described ACTp as useful and attributed positive changes to the ACT processes, or they reported difficulty understanding some exercises, were ambivalent about the usefulness of some aspects of therapy, and made fewer changes in their lives. Despite this, all described some positive outcomes of their participation in ACTp. All participants recommended ACTp and reported therapy as useful, indicating subjective efficacy, acceptability of therapy and client satisfaction for this group of individuals, as found elsewhere (White et al., Reference White, Gumley, McTaggart, Rattrie, McConville and Cleare2011). These factors are likely to contribute to attendance and uptake of therapy by clients thus contributing to the overall effectiveness in routine practice.

Theoretical implications

The theme “useful processes” indicated that values, mindfulness, defusion, and acceptance are psychologically active processes in ACTp, in keeping with the underlying theory. Not only were participants able to describe experiences that were identifiably congruent with these theoretical processes, they also attributed improvements in intensity of symptoms, behaviours and distress to them. This clearly suggests that, for this client group, these processes, and the ACT model (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999) more generally, are accessible and useful.

Process research in ACTp has identified mindfulness as a mediator of emotional adjustment to psychosis (White et al., Reference White, Gumley, McTaggart, Rattrie, McConville and Cleare2011) and believability as a mediator of symptom distress and rehospitalization (Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes and Herbert, Reference Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes and Herbert2012). This study extends identification of an active role for these processes to participants with psychosis by describing as useful two additional ACT processes, namely values and mindfulness (for symptoms of psychosis).

Research has found values has a mediating role in ACT for epilepsy, generalized anxiety disorder and pain (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2009; Lundgren, Dahl and Hayes, Reference Lundgren, Dahl and Hayes2008; Vowles, McCracken and Zhao-O'Brien, Reference Vowles, McCracken and Zhao-O'Brien2010). In the current study, participants associated values work with giving life a sense of meaning and purpose and improved goal directed behaviour. Committed action is closely related to values and the ACT model predicts an increase in values-directed behaviour associated with values clarification. However, a direct link between values and action was not entirely clear in participant reports. For the current participants, continuing to act despite symptoms and achieving at least one positive behavioural change related to goals suggests at least committed action and implies the presence of valued direction.

The current study is consistent with White et al. (Reference White, Gumley, McTaggart, Rattrie, McConville and Cleare2011) in suggesting mindfulness as an active ingredient in ACTp: participants viewed mindfulness as an important, active technique in ACTp that contributed to change. However, a key finding was the theme of mindfulness as being useful in order to relax and distract rather than non-judgementally paying attention to self and context. Although it is possible that therapists’ explanations of mindfulness for participants, or guidance in learning, may not have been adequate, we consider this unlikely given their experience and supervision. We also consider that most participants were indeed practising at least basic mindfulness during therapy sessions, given the frequency of guided in-session practice. Another explanation seems possible: given the pervasiveness of attention, memory and learning challenges experienced by this population (Tandon et al., Reference Tarrier, Kinney, McCarthy, Humphreys, Wittkowski and Morris2009; Weickert et al., Reference Weickert, Goldberg, Gold, Llewellen, Egan and Weinberger2000) construing mindfulness as “relaxation” may be a familiar way for participants to understand and describe the complex construction of mindfulness, especially given the direction of attention to breathing and bodily sensations in basic mindfulness exercises. If so, this has two implications: first, this incorrect labelling as relaxation works against retaining and expanding the elements of mindfulness that are not cued by the association with relaxation; second, it suggests, for this population, that greater attention by therapists to easily-understood labels that reinforce the practice of mindfulness through highlighting clients’ experience of it may be beneficial.

While participants reported no change in the frequency of positive symptoms, the reduction in the intensity and associated distress suggests a change in relationship with these unwanted private experiences – a key prediction from the model (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999). In previous ACTp research, this change has been understood primarily via two constructs – believability and psychological flexibility. Previous ACTp research found “believability” – the extent to which a symptom is considered to be true – negatively mediates associated distress (Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes and Herbert, Reference Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes and Herbert2012; Gaudiano et al., Reference Gregg, Callaghan, Glenn, Hayes and Glenn-Lawson2010). In this study, participants reported a change in perspective towards unwanted private events, viewing them with less seriousness and legitimacy, a change that may be picked up by ratings of believability in previous research (Bach and Hayes, Reference Bach and Hayes2002; Bach et al., Reference Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes and Herbert2012). Participants also described continuing to act despite symptoms. This may be indicative of ACT's integrative construct of psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999) – contacting the present moment and changing or persisting in behaviour consistent with values (Hayes, Reference Hayes2004). These results suggest that a focus on reducing the impact of persistent symptoms of psychosis, rather than a reduction of symptoms, improves functioning, a central theme of ACT. Participants’ reports suggest a broadening of the repertoire of responses to persistent symptoms, an increase in psychological flexibility, and engagement in activity. Whether this behaviour is in accordance with identified values was not reported in this study.

The theme “non-specific therapy factors” indicates all participants valued the warm, professional style of the therapist and the freedom to talk. Four participants described the lack of negative judgements by the therapist and feeling listened to as contributing to improved self-esteem and self confidence. Although therapist factors influenced non-specific beneficial outcomes they were not sufficient to generate specific symptom and behaviour change. No non-specific therapy factors or non-ACT processes were reported to directly contribute to symptom change. This is consistent with literature that suggests the therapeutic relationship is one essential therapy component (Messari and Hallam, Reference Milton and Ma2003; Tarrier et al., Reference Tarrier, Kinney, McCarthy, Humphreys, Wittkowski and Morris2000).

Clinical implications

Participant views of ACTp suggest differences in their understanding of therapy. The theme “understanding therapy” indicated participants either understood therapy and the experiential exercises involved or they did not connect with therapy or had a poor understanding of some exercises. Whilst reporting a good understanding of therapy, some participants acknowledged the potential difficulty other people may experience in understanding some exercises and metaphors. While ACT tends to de-emphasize conventional language use and relies on symbolic and experiential techniques (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999), the abstract nature of the experiential exercises may interfere with making connections to the underlying meaning and generalizability of the concept. This is a potential barrier to therapy effectiveness, especially for people whose cognitive functioning may be impaired (Tandon et al., Reference Tarrier, Kinney, McCarthy, Humphreys, Wittkowski and Morris2009; Weickert et al., Reference Weickert, Goldberg, Gold, Llewellen, Egan and Weinberger2000). In a recent case study, Veiga-Martinez, Pérez-Álvarez and García-Montes (Reference Veiga-Martínez, Pérez-Álvarez and García-Montes2008) cautioned that the amount and complexity of metaphors should be reduced when working with psychotic clients. They recommended that an “excess of abstract symbolic stimulation could confuse the client more than it orients him” (p. 132). This study partially supports this recommendation. The conflicting views held about the usefulness of therapy illustrates both a difficulty in connecting with some experiential exercises and metaphors, as well as benefits of particular exercises (e.g. mindfulness of the five senses vs mindfulness of the breath). Some clients could benefit from greater therapist attention to their understanding of the connection between experiential exercises and their underlying meaning, and attention to tailoring metaphors and exercises to the client. Further differences to which participants drew attention included the phase of illness at the time of therapy and interview, medication adherence, and past exposure to related therapy concepts. It is likely these factors impacted on clients’ understanding of therapy and affected the degree of change, for example, previous experience with mindfulness reportedly assisted with understanding of related concepts, yet also challenged another participant's prior understanding of the concept of mindfulness. Therapists may need to spend more time (and more regularly) orientating some clients to therapy. These approaches may go some way to assist with clients’ understanding of therapy.

For at least half of the current participants values work was reported as useful to provide meaning and guide direction, or work towards goals. This is consistent with the shift toward recovery-orientated mental health service provision (Ramon, Healy and Renouf, Reference Ramon, Healy and Renouf2007; Department of Health, 2007) in which values work may assist to re-establish or identify new value-based goals to foster hope and meaning, and rebuilding a positive identity (Andresen, Oades and Caputi, Reference Andresen, Oades and Caputi2003; Bellack, Reference Bellack2006; Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison, Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison2007). This is especially so for individuals with persistent symptoms, where goals to eliminate symptoms or return to previous functioning may not be feasible.

Continuing to act in spite of symptoms is an important outcome for this population. Individuals experiencing a psychotic disorder are often significantly impaired by persistent symptoms and associated distress and can find it particularly difficult to take steps towards improving their lives. Steps towards action in the presence of ongoing symptoms are important to facilitate movement in the direction of recovery, meaningful activity and reduced associated distress. An interesting finding was that some defusion exercises and mindfulness were not useful when participants were overwhelmed by intense psychotic experiences or negative thoughts. Schizophrenia is associated with information processing difficulties including selective attention for task relevant stimuli and diminished attention capacity (Alain, Hargrave and Woods, Reference Alain, Hargrave and Woods1998; Forbes, Carrick, McIntosh and Lawrie, Reference Forbes, Carrick, McIntosh and Lawrie2009). The attention control required in these ACT processes may be too demanding when experiencing intense experiences and associated distress, resulting in overloaded attention control and feeling overwhelmed. Veiga-Martinez et al. (Reference Veiga-Martínez, Pérez-Álvarez and García-Montes2008) found closed-eye exercises (mindfulness) (closing one's eyes and paying attention to inner experiences) sometimes increases auditory hallucinations and distress, as was reported by one participant in this study. In a single case study of ACTp, Bloy, Oliver and Morris (Reference Bloy, Oliver and Morris2011) also reported this technique led to an increase in distracting paranoid ruminations. Reducing the cognitive demand in tasks by simplifying or shortening exercises, and more therapist support, may be useful in these instances.

Participants’ reports that mindfulness was useful to “relax and distract” are not aligned with the aim of mindfulness. Despite participants’ difficulty describing and/or understanding the concept of mindfulness, participants reported some benefits. Mindfulness was described as an important process to reduce distress, anxiety, negative thoughts and paranoia and “focus on what's real”, leading to positive client change. Despite the mismatch with the underlying theory and in light of the reported benefits (whilst considering the potential impact with intense experiences or possible exacerbation of symptoms), mindfulness should not be overlooked as a useful intervention for this population.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

This study is not without limitations. First, the ACT processes clients can report are inevitably influenced by the breadth and frequency of the processes that participants were exposed to. The prominence of mindfulness is at least partly attributable to its frequent use – the manual recommends mindfulness be utilized in each session; however, this does not detract from reports of its usefulness. Further, whilst the therapist's rationale is not available to the researcher, it appears values, acceptance, mindfulness and defusion were the components judged by participants as the most appropriate and useful, but this could also reflect the therapists’ judgements. Second, the broader applicability of these results should be considered with caution given the use of convenience sampling, rather than theoretical and random sampling. The timing of the study during the final phase of an RCT limited the availability of participants. Nevertheless, recruitment continued until there were no more available ACTp participants. Further, the final interviews resulted in corroborating data with only one new sub-theme and some variation in the perceived benefits from the therapeutic relationship. This suggests a move towards data saturation and the results of this study provide some insights into the active therapeutic components of ACTp from a client's perspective.

Further research exploring the long term perceived usefulness of ACT processes would provide a clearer understanding of the ongoing benefits of ACTp for this population. To inform therapy and further explore the usefulness of ACT, future research should explore specific difficulties experienced by participants in understanding aspects of therapy and the extent to which strategies were implemented outside of therapy. In ACT, “mindfulness is defined as a combination of acceptance, defusion, the present moment and transcendent sense of self – a powerful all in producing therapeutic change” (p. 332, Fletcher and Hayes, Reference Fletcher and Hayes2005). With this definition in mind, further investigation into what aspects of mindfulness are considered useful would clarify the role of this process and its active component(s). In addition, investigating barriers to treatment, particularly understanding of therapy and connectedness to exercises will further refine the application of ACT in psychosis.

Conclusion

This study investigated the ACT processes in psychosis from the client's perspective. Mindfulness, defusion, acceptance and values were reported by participants as useful to reduce stress, provide direction and meaning in life, and reduce distress associated with unwanted private events. While there was variation in participants’ views and understanding of ACTp, all participants reported at least one strategy as useful. The study findings provide support for the theoretically defined model underlying ACT in psychosis. Adapting the basic principles of ACT to suit the needs and characteristics of the individual to achieve the best possible outcomes is likely to impact on understanding of therapy and beneficial changes. Some modifications of the therapy to accommodate the cognitive and symptom features of psychosis are warranted.

Appendix A

Example interview questions

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.