In 1867, leading wine growers in northeastern Hungary published the Album of the Tokay-Hegyalja, an introduction to one of Hungary's most venerable wine districts. Handsomely illustrated and with parallel text in English, French, German, and Hungarian, the book aimed “to make known to the civilised countries the birthplace of the far famed Tokay wine” and “to point out the existing means of communication and other circumstances which are favourable to the extension of the commercial relations of the Hegyalja wines.”Footnote 1 Hungary, the growers asserted, was destined to play an important role in the “general advance of nations,” and they believed that their wine could increase its “prosperity and influence.” This was a grand vision, born of confidence and based on hope, and one well-suited to the year in which the Ausgleich granted Hungary wide autonomy within the Habsburg Empire. The Album acknowledged that practical difficulties remained and conceded that many growers’ cultivation methods and quality of wine left much to be desired. Such doubts, however, paled in comparison to the certainty that their wine should occupy a special place in Hungary and in Europe.

Many other nineteenth-century Hungarians agreed, and they tirelessly touted wine's virtues in scientific studies, sales prospectuses, newspaper editorials, local histories, and patriotic poetry. Surveying this literature, scholars have shown how wine became an integral part of the Hungarian “imagined community” in the nineteenth century. In a wonderful book, A bor mint nemzeti jelkép (Wine as National Symbol, 2003), Ferenc Benyák and Zoltán Benyák documented how national-minded writers exploited well-worn stereotypes (Hungary as a “country of blessed wine production and grape cultivation par excellence,” which separated it from its neighbors, beer-chugging Germans and brandy-swilling Slavs); elevated lusty wine-drinking songs (the poets’ mid-century bordalok); exalted local traditions, from village dances to harvest festivals; and emphasized the centrality of wine to all social classes and regions inhabited by Magyars.Footnote 2 This appropriation of popular culture largely succeeded, and by the late 1800s it had secured wine's place among the national symbols of Hungary. In this, Hungary was little different from France, Portugal, and other wine-drinking countries.Footnote 3 Indeed, across Europe a wider nationalization of food and drink was taking place. Nowhere was this process smooth or uncontested or complete; as anthropologist Orvar Löfgren has written, it involved “a complex pattern of accommodation, reorganization, and recycling, in which different interest groups have different claims at stake.”Footnote 4 Yet the association of certain foods and drinks with national communities was difficult to resist, and it continues to the present day.

Hungarian wine looks very different, however, from the vantage point of social and economic history. Scholars working in these fields have confirmed that agriculture remained the engine of economic growth through World War I.Footnote 5 During this period outputs rose spectacularly for many crops—corn, wheat, potatoes, and sugar beets—thanks to mechanization, wetlands drainage, crop rotation, and chemical fertilizers. At the same time, historians have analyzed the many problems that plagued rural Hungary, including limited social mobility, low rates of education, and a rising tide of emigration. The worst of these ills had long spared wine-growing regions, where peasant families typically had a few vines and supplemental incomes from farming, crafts, and wage labor. But a flurry of blows battered the wine sector in the late 1800s. The most destructive, and the prime mover in this study, was phylloxera vastatrix—the “dry leaf devastator”—a tiny parasitic insect that crippled the leaves and roots of grape vines and left them vulnerable to deadly plant pathogens.Footnote 6 Like the potato blight of the 1840s, this pest wiped out huge swathes of agricultural land across Europe, and it's estimated that in much of Hungary, land under cultivation fell by nearly half and total output of wine by three-quarters. Globally, the fight against phylloxera had far-reaching consequences: it revolutionized plant science, remade trade networks, altered drinking patterns, and deeply influenced the geography of wine production. Its effects can also be felt today, however faintly.

This article attempts to tie together these two distinct historiographical threads, one that leads to nationalization, the other to devastation. It does so by narrowing the focus and by drawing on research conducted on a small, easily overlooked village in the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine region. The name of the village is Tállya, and it was one of thousands of settlements in prewar Hungary that produced grapes and wine. This case study, I would argue, can tell us much about nineteenth-century practices of viticulture, as well as how ordinary people responded to a global catastrophe and what the arrival of modern agriculture meant on the ground.Footnote 7 Tracing the village's history from the 1860s to World War I, the article makes three main claims. First, it demonstrates that from the start, this remote village belonged to wider networks of trade and exchange that stretched across the surrounding region, state, and continent. Second, it shows that even as Magyar elites celebrated the folk culture and peasant smallholders of this region, they also cheered the introduction of what they saw as scientific, rational agriculture. This leads to the last argument: wine achieved its place in the pantheon of Hungarian culture at a moment when the local communities that had grown up around its production and stirred the national imagination were undergoing dramatic and irreversible change.

Before the Storm

Today Hungary is a small country and a minor player in the global wine market. A century and a half ago the Kingdom of Hungary was an integral part of the Habsburg Empire and a major producer of wine. Károly Keleti, author of a landmark 1875 statistical survey of Hungarian viticulture, ranked it well ahead of Austria, on par with Italy and Spain, and behind only France, the world hegemon.Footnote 8 Keleti tallied thirty-seven historic wine regions, some of which produced premium wines known well beyond its borders. An 1881 prospectus aimed at British buyers listed several “wines of the first class,” which included Oedenburg and Ruszt, white wines from western Hungary, as well as a strong red, Menes, from the region around Arad, in present-day Romania.Footnote 9 Pride of place belonged to Tokay, which was celebrated for its medicinal properties and exquisite, brilliant color. An enthusiastic French playwright from the era described it as “a delicious, sublime, ethereal, phosphoric, poetic wine, of a prodigiously invigorating power, although containing not abundant alcohol.”Footnote 10 Such encomiums tell us much about the wine's high reputation but say little about the conditions under which it was produced. This section uses Tállya to survey the region's long history of viticulture and to document the many difficulties growers faced in the nineteenth century.

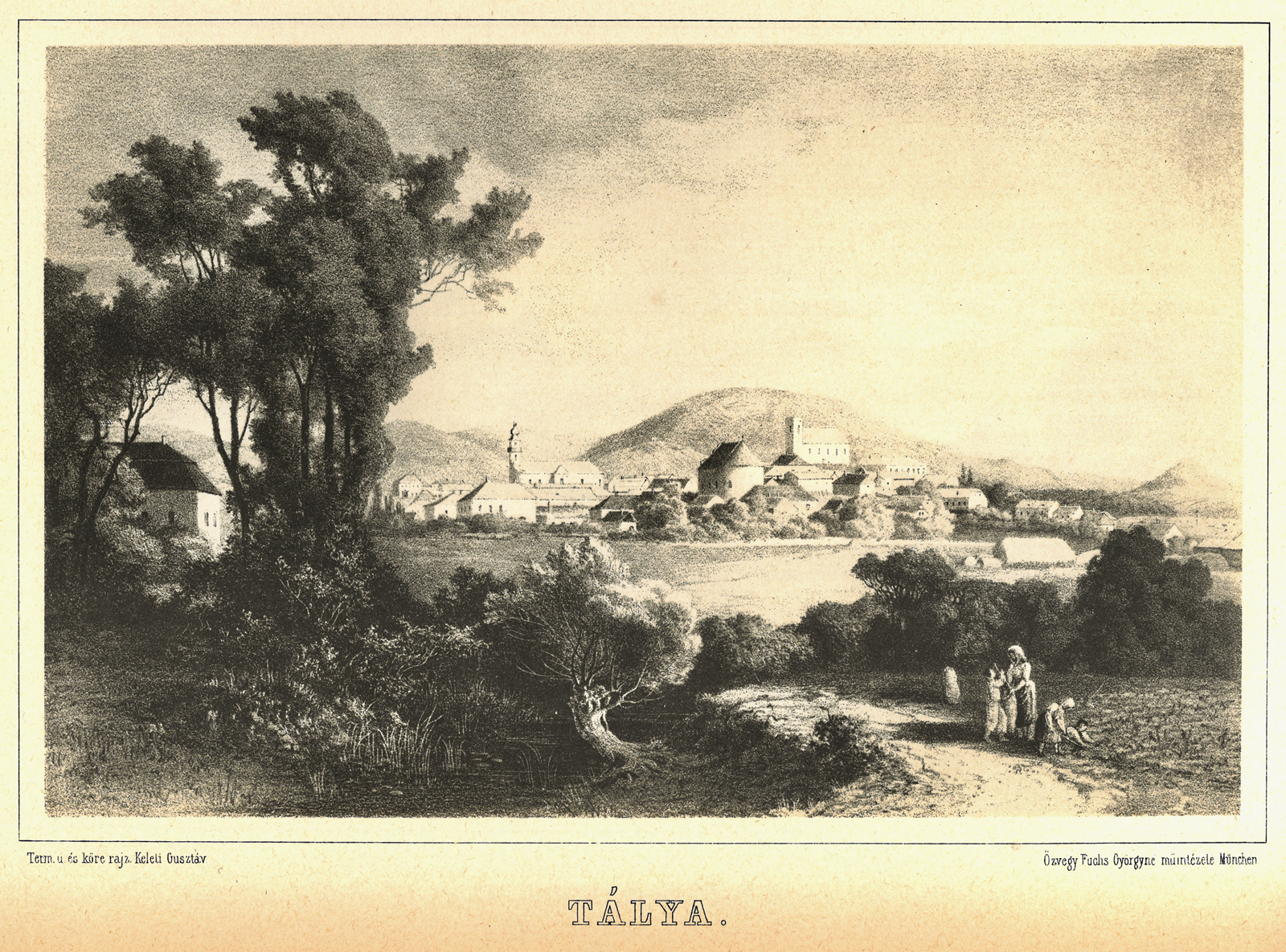

Viticulture had old, deep roots in Hungary. Indeed, the name of the village studied here—Tállya—comes from an Old French word (taille) meaning “cleared land” and seems to have arrived with winemaking Walloon settlers in the Middle Ages.Footnote 11 The village grew up along a road hugging the Zemplén Hills, whose sun-drenched southern slopes more than compensated for the region's northern latitude. By the seventeenth century, the village's wines had won renown in Rome and buyers in Poland and Russia; within Hungary, its boisterous harvest festivals attracted mighty aristocrats and admired musicians, such as the Roma violinists János Bihari (1764–1827) and János Lavotta (1764–1820), whose songs are still played today. In the late 1800s, the village's population hovered around 3,500. It had more than six hundred houses, for the most part constructed of stone or brick and topped with wooden shingles (although nearly one-quarter still had thatched roofs in 1900). The village had three churches and a synagogue (Figure 1). It counted one great landowner, the unloved but wealthy Baron György Maillot, who single-handedly accounted for one-third of the village's property taxes, and a dozen other families who owned good-sized properties.Footnote 12 Most residents, however, worked as craftsmen or agricultural laborers or eked out a living from vines on small plots, often no more than half a hectare. Even so, individual families sometimes worked the same vineyards for multiple generations, passing down traditions, tools, and hard-won knowledge about the local environment.

Figure 1: An 1867 lithograph of Tállya, with its churches and vineyard-clad hills. Source: Joseph Szabó and Stephen Török, eds., Album of the Tokaj-Hegyalja (Pest, 1867), 42.

Local conditions posed steep challenges even for seasoned growers. Tállya lies in Tokaj-Hegyalja, one of the most famous wine districts in Hungary. It has low, gradual hills; clayey, volcanic soil; cold, cloudy winters; and hot, dry summers.Footnote 13 Under the right conditions, these combine with certain grape varieties to produce Botrytis cinerea, or “noble rot,” a gray fungus that infects ripe grapes left on the vine. The result is aszú wine, better known under the regional appellation Tokay/Tokaji. This sweet, sophisticated white wine is highly prized and well-traveled: Thomas Jefferson drank it at Monticello and Goethe placed it in his Faust (“Tokay shall flow for you,” promises Mephistopheles).Footnote 14 County and royal authorities long struggled to protect its reputation and combat falsification by demarcating the wine region's borders, classifying its vineyards, and requiring sellers to use special barrels. Like the authors of the Album of the Tokay-Hegyalja, they hoped to increase exports, particularly after sales to Poland and Russia started to decline in the late eighteenth century, the result of the partition of Poland, recurrent warfare, and the growing popularity and availability of French wine. The dreams of substantial exports to western Europe were only partly realized, but they helped cement the wine's reputation, which has survived more or less intact down to the present.

This tells only part of the story. In the nineteenth century, “noble rot” appeared roughly one year in three, and then only in some vineyards, with the result that just one out of six years brought significant quantities of high-quality aszú wine.Footnote 15 Most harvests yielded more ordinary grapes, which produced white wines of varying quality and which growers often sold cheaply. Some of this wine was sent to Austria, but, as was common across Europe in this era, the bulk of it was consumed at home, sold in local taverns, or shipped to nearby cities and towns. In places like Tállya, landowners had few other options. The village had ample vineyards, perched on the surrounding hillsides, but little good land for meadows, pastures, or crops. Wine was close to a monoculture, leaving locals dangerously exposed to frosts, hail, rainstorms, cold, and drought. Myriads of pests—hungry swallows, straying cows, and crafty hamsters—added to their headaches. Growers responded to these trials in multiple ways, including a strong adherence to traditional methods, carefully organized labor relations, and extensive communal participation.

Nineteenth-century vineyards looked very different than they do today. In this region, one could see wattle fences, terraces, and corner border markers, as well as crucifixes, chapels, and statues of patron saints (work in the vineyards was closely tied to the liturgical calendar). Many parcels were irregularly shaped: a cadastral map from 1868 shows long, narrow strips; straightforward squares and triangles; and convoluted heptagons and octagons.Footnote 16 Closer to the ground, stakes and trellises were uncommon, and vines usually grew in uneven bunches and not in the neat rows one sees nowadays. As their predecessors had done, workers used pruning knives and trained vines to grow into a low head shape; this produced grape bunches close to the soil, from which they absorbed heat and developed sweetness.

Less visibly but no less significantly, Tokaj-Hegyalja's vineyards contained many grape varieties. A survey in 1855 found eighty-nine different varieties in the region.Footnote 17 This was true across Europe and had a certain logic: according to James Simpson, “Many small growers planted a selection to reduce the risk that their whole harvest would be lost, as varieties differed in their susceptibility to extreme weather conditions or the presence of disease and pests.”Footnote 18 A single vineyard would produce a medley of grapes, which peasants also believed produced better wine.

Successful viticulture demanded both physical strength and practiced skill. Stretching from early spring to late fall, the cultivation of grapes involved as many as fifteen steps, including the backbreaking work of turning over and hoeing the soil multiple times (horses and oxen could not be used on steep hillsides and among scattered vines).Footnote 19 Because inept grafting, pruning, or tying could ruin a vine, expert hands were needed for many tasks. This largely explains why employers in Tokaj-Hegyalja had long preferred wage labor to serf labor and why the abolition of serfdom in the mid-nineteenth century did not fundamentally change labor relations in this region. All members of a family pitched in, with men hoeing and pruning and with women, paid much less, tying and picking the grapes. Large landowners usually employed a vigneron (vincellér) to oversee all work in the vineyard, with the goal of maximizing harvests and minimizing labor costs—sometimes by plying workers with brandy instead of cash. The village's vineyard owners also drew up written bylaws to protect and police their properties.Footnote 20 These authorized the election of a hill judge (hegybíró), who provided year-round supervision of vineyards, roads, bridges, press houses, and the hundreds of underground wine cellars that lined the village's roads. The hill judge also oversaw the many guards, the hegypásztorok—literally, “hill shepherds”—who worked from early August until the harvest in October or November, protecting the ripening grapes from thieves, both human and animal.Footnote 21 Guarding the grapes was low pay, low status work, and yet in Tállya it offered seasonal employment to nearly one hundred local men. Happily, the agricultural cycle's monotony and strain were broken by periodic celebrations: lively balls during Carnival, noisy quarterly markets, and rollicking harvest festivals, complete with firework displays and signal fires to greet neighboring villages.Footnote 22 Wine flowed freely through all these events, which could strengthen social cohesion and local identity.

Labor practices and agricultural methods in Tállya were not unchanging. Some practices—the making of aszú wine, the head-shaped training of vines, the employment of “hill shepherds”—had been employed for centuries. Many contemporaries emphasized these continuities: “The Tokaj-Hegyalja harvest is essentially the same today as it was centuries ago,” wrote one official.Footnote 23 For this reason, we can speak with some confidence about the long-term stability and intergenerational transfer of local knowledge and traditions. Even with this solid foundation, however, growers faced tremendous uncertainty from year to year.Footnote 24 For example, in 1870 the Tokaj-Hegyalja region produced 110,000 hectoliters of wine. A decade later—well before phylloxera had made an impact—output had dropped to 35,000 hectoliters. Production of the valuable aszú wine fluctuated even more significantly, with some good years producing nine times the output as in bad years. This variability had much to do with weather, and according to one nineteenth-century observer, the vine-grower's “hopes go up and down with the barometer.”Footnote 25 For all their apparent stability and outward solidity, then, vineyards often concealed what anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has called “the story of precarious livelihoods and precarious environments.”Footnote 26

External events added further disruptions and disjunctures. Wars in particular could bring violent transformations, from the distant depredations of the Fifteen Years’ War (1591–1606) to the future deportations of World War II. The Rákóczi War of Independence (1703–11), usually hailed as a proud moment in Hungarian history, brought only misery to this winemaking village, which lost four-fifths of its population.Footnote 27 Those who remained rebuilt and replanted, but natural disasters threatened when human-made ones did not. Starting in the late 1850s, successive droughts, fires, and frosts brought widespread hunger and forced village leaders to open soup kitchens. Records compiled several years later revealed that during the crisis hundreds of residents had borrowed money from the authorities and not paid it back.Footnote 28 Not surprisingly, the population declined by nearly 10 percent in the decade that followed, when still more calamities hit, including an 1877 fire that destroyed more than one hundred houses and caused two hundred thousand florins of damage, more than thirteen times the village's annual budget.Footnote 29

Such disasters could strengthen the grip of familiar ways. In Peasants into Frenchmen, Eugen Weber wrote that traditional methods provided “discipline and reassurance” in an era defined by poverty and “desperate circumstances.”Footnote 30 But as Edit Fél and Tamás Hofer demonstrated in their classic Proper Peasants, the disruption of village life could also make locals open to new agricultural methods, tools, and beliefs.Footnote 31 With the sources at hand, it is difficult to know just how receptive to innovation Tállya's peasant smallholders were. More certain is that many large landowners and officials believed that things had to change, even if there was little consensus on how or in what direction. In 1859 the Tállya vineyard owner, winemaker, and magistrate János Sóhalmy published a series of newspaper articles in which he bemoaned the region's lost glory.Footnote 32 Looking backward, he conjured images of a precapitalist idyll, in which benign aristocrats, contented workers, and honest traders had brought prosperity and fame to Tokaj-Hegyalja. In recent decades, he alleged, the region had declined as fraud proliferated, workers left, Jews took over the wine trade, and misery spread. Citing France as a positive model, Sóhalmy urged the Hungarian government to police the production of wine and support its export. The Tokaj wine merchant István Burchard shared Sóhalmy's dim view of the present and antipathy to Jews.Footnote 33 Yet he also claimed that most growers’ cultivation of grapes and winemaking methods were deeply flawed (sparing no one, he tartly noted that the terrible smell he encountered in one aristocrat's wine cellar betrayed a complete lack of expertise). Writing more than a decade later, the statistician Keleti was less polemical and more farsighted. Although he took pride in Hungarian viticulture, he too asserted that “weak and purposeless handling” had ruined the quality and reputations of many of its wines.Footnote 34 Smallholders, he observed, worked hard but few had the knowledge, interest, or capital required to adopt newer practices of growing and winemaking. For Keleti, the future lay in France.

Something else lay in France: phylloxera, which would remake viticulture in Tállya and settlements like it. But long before this storm hit, other global forces had made their way through Hungary's vineyards and villages. The tastes of Russian drinkers, the policies of French officials, and the turmoil of distant wars had all shaped the fortunes of growers even in remote places like Tállya. Locals contended with these forces by relying on familiar methods and carefully managing their labor; they were adaptable and resilient, if not fully market oriented. Their villages also displayed elements of the folk culture so prized by nationalists: the harvest festivals, tight-knit communities, well-tended vineyards, barrel-filled cellars, and celebrated wine. But when national-minded observers—men like Sóhalmy, Burchard, and Keleti—looked more closely, they found much less to admire. Although their studies and pamphlets shed more heat than light, they did illuminate issues identified by later economic historians, including the region's lack of capital and poor quality control. Thus Keleti, the most perspicacious of them, was torn between praising the innate virtues of Hungarian peasants and listing the innumerable faults of their work. Unexpectedly and suddenly, phylloxera would resolve this dilemma.

The Storm

Wine was an early global commodity, and by the early 1800s viniculture had spread to six continents. Far-flung grape growers and winemakers readily exchanged vines, techniques, and tools. In so doing, they hastened the global diffusion of pests and pathogens that preyed on grapevines. Such was the case with phylloxera, which originated in the United States and gradually made its way around the world. Scholars have carefully mapped its spread and shown how transnational networks could be used to share successful remedies as well as scientific misconceptions.Footnote 35 Phylloxera was devastating for the peasant smallholders who produced the bulk of the world's grape harvest, and for many recovery came slowly or not at all. Officials, large landowners, and agricultural experts also struggled to grasp the enormity of the disaster. But some saw a silver lining in this terrible storm, which, they hoped, would sweep aside the old ways and make room for more efficient, modern forms of production. In this they anticipated the findings of later historians, who, in surveying the long but victorious battle against phylloxera—alongside breakthroughs in transportation, refrigeration, chemistry, and botany—have located the “the formation of a totally new, scientific, viticulture” in the early twentieth century, with France at its center and the source of knowledge and expertise for the rest of Europe.Footnote 36 Evidence for this can be found in Hungary, where by 1910 total wine output had recovered and reached pre-phylloxera levels on significantly reduced acreage. Again focusing on Tállya, this section shows how dramatically phylloxera changed viticulture in Tokaj-Hegyalja.

In Hungary, phylloxera was slow to arrive but devastating once it did. Discovered in the United States in 1856, it rapidly crossed the Atlantic to Europe, presumably on imported American grapevines. Reports of widespread damage to vineyards began to arrive from southern France in the early 1860s, but it took years for growers and scientists to identify the cause and even longer for them to figure out workable solutions. The pest meantime spread from vine to vine, from vineyard to vineyard, and from wine region to wine region.Footnote 37 It raced across France and skipped across international borders, ravaging vineyards in Portugal and Switzerland, although moving more slowly through Spain and Italy. By the 1870s it had reached Klosterneuburg in Austria, prompting Keleti to urge the Hungarian government to learn from the Austrians and then act decisively.Footnote 38 In 1882 the government passed a law that adopted international practices established at the recent International Phylloxera Convention held in Bern, Switzerland. Hungary pledged to control and closely supervise the import and export of grapes, vines, and rootstocks; to inspect vineyards and nurseries; and to carefully monitor the progress of the blight. Antiphylloxera committees were established on the county and local levels. Yet such actions were uncoordinated and ineffectual, and when phylloxera began to spread across the Hungarian Kingdom in the mid-1880s, it still seemed to catch everyone unaware.Footnote 39 In just a few years, it reached every wine district, leaving a path of destruction in its wake. In Tokaj-Hegyalja, this “Tamerlane of the insect world” reduced acreage of land under cultivation by close to 90 percent and wine production by two-thirds.Footnote 40 Newspapers warned that this “pearl of the nation” could be lost, and with it the livelihoods of sixty thousand “purely Hungarian people” (tősgyökeres magyar ember), who, in their desperation, might embrace socialism or choose emigration.Footnote 41

Phylloxera overwhelmed Tállya. Nearly all vineyards were struck, including those of the poorest peasant and those of Baron Maillot. A woman who grew up in the village recalled that the blight brought only “poverty and sorrow.”Footnote 42 The writer Géza Gárdonyi visited in 1892, ostensibly for a celebration, the ninetieth anniversary of Lajos Kossuth's birthday and of his baptism in Tállya's Lutheran church.Footnote 43 He found little cause to celebrate. The village, he wrote, was “sad and silent. The people act as though an invisible hand beats them every day. Barren, lifeless hills stand around the town.” A dismal guesthouse, whose owner claimed he had not seen a guest in three years, did little to add to the cheer. The locals, Gárdonyi observed, worked desperately to stay afloat, and some were angry at the government for failing to eradicate phylloxera and for not offering more help, as they felt France had done for its ruined growers. The village itself could do relatively little. Already in 1887, its council had supported plans to establish a nursery with phylloxera-resistant American vines and called for financial relief for local growers.Footnote 44 But records from 1892 reveal a view as bleak as Gárdonyi's, in which village leaders despaired about “the laboring class's lack of work” and “the middle strata of vineyard owners struggling with privation and doing without their daily bread and forced, like beggars, to seek a new home.”Footnote 45

Solutions to the phylloxera crisis came only slowly. Although Hungary could benefit from knowledge accrued and shared across Europe from the 1870s onward, there were many missteps and false hopes. Desperate vineyard owners mixed naphthalene, petroleum, and compounds of arsenic and sulfur into the soil surrounding the vines’ roots, but with little effect. Contemporary newspapers published reports of hopeful but fruitless solutions, from the parish priest who soaked infected vinestocks in soapy water to the Viennese chemist who recommended his “Universal Insect Salt,” also useful against mice and rats.Footnote 46 In the end, Hungarian officials and agronomists largely followed the lead of their counterparts across Europe. They learned that inundating grapevines could destroy phylloxera, but largely dismissed this solution as impractical, given the hilly, dry locations of most vineyards. They also showed an aversion to direct planting of American varieties, preferring to maintain more familiar and time-tested cultivars. Three other methods were instead adopted. First, grapevines were planted in sandy soil, which proved largely inhospitable to phylloxera and could be found in most wine regions. The great expansion of viticulture on the Alföld, the Great Hungarian Plain, dates from this period, and what the resulting “sand wines” lacked in quality they made up for in quantity. Second, growers began to pump carbon disulfide into the soil around their vines using large, syringe-like injectors. This procedure was relatively expensive, technically difficult, and often unreliable, but it protected some vineyards for a few years at least. The long-term solution lay in the third and most widespread method: the grafting of Hungarian grape varieties onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks, which were first imported from France and then produced domestically. When the Hungarian government threw its weight behind this program, it proved to be the most cost-effective and durable solution, and it allowed regions like Tokaj-Hegyalja to reconstruct their ruined vineyards.

In Tállya, efforts to replant began almost immediately. The village was fortunate to have several large landowners who joined the fight against phylloxera. Foremost among them was Gyula Szabó, a local pharmacist and vineyard owner.Footnote 47 Soon after the blight appeared, Szabó traveled to France at his own expense, where he studied how to combat phylloxera (possibly in Montpellier, the center of French research). Returning to Tállya, he experimented with different American varieties and eventually settled on Riparia portalis as best suited to the local soil and climate. Propagating this vine, he offered to share it with local owners and instruct them in the delicate art of grafting domestic scions onto American rootstocks. He apparently had to overcome much resistance, especially from poorer growers suspicious of innovation and short of capital. Village leaders were little better: although the council “readily offered its moral support,” it backed this up with just twenty-five forints, a paltry sum.Footnote 48 Yet with the initiative of men like Szabó, the financial resources of the Hungarian government, and—no less importantly—the hard work of hundreds of individual growers, the vineyards of Tállya recovered. When the minister of agriculture, Ignác Darányi, visited the village and surrounding region in 1898, he stated that reconstruction “had far exceeded his hopes” and promised that Tokaj-Hegyalja “would be more beautiful than it had ever been.”Footnote 49 By the turn of the century, many growers had replanted their vineyards, and with such efficiency and zeal that within a decade overall production had reached pre-epidemic levels, even though total acreage had fallen.

Reconstruction and recovery came at a cost, a point obscured in histories that emphasize the modernization of agriculture. During his visit in 1898, the minister of agriculture maintained that the state had a duty to help smallholders. But he meaningfully added that “nowadays, viticulture no longer follows the old course, but constitutes an entire science,” making it clear that growers would have to change their methods. His ministry's experts, he promised, would soon issue a thick book with 350 illustrations to show smallholders the new ways.Footnote 50 It would also support nurseries, regular training courses, agricultural experiment stations, and temporary tax relief to speed this process forward. Reconstruction would not happen overnight, and experts repeatedly complained about the tight hold of tradition in the villages. In the words of one official: “unfortunately, it was not only the ordinary grape growers, but also the more intelligent vineyard owners, who, with relatively few exceptions, did not show confidence in these methods, and to a certain degree betrayed hostility.”Footnote 51 Perhaps growers understood that reconstruction required more than American rootstocks and agricultural handbooks; it demanded new skills and techniques and a new outlook on winemaking. A historian of French wine has described the long-term shift in mentalities that the phylloxera crisis brought about: “In this period, wine production became an industry that required producers to think about capital inputs, invest in machinery, secure credit, acquire technical training, and constantly innovate and adopt new technologies to remain economically viable.”Footnote 52 In Hungary, where capital, technology, and access to global markets were scarcer than elsewhere, the spread and adoption of this way of thinking would come slowly and unevenly.

Change in the vineyards was more immediate and visible.Footnote 53 Vineyards crept down the hillsides, where they were easier to access, work, and water, if less likely to produce exceptional wines. With fewer owners, plots of land became more equal in size and uniform in shape. Workers pruned and trained vines differently, used new tools (augers, plows, pruning shears), and took greater care in the wine cellars (using iron presses in the place of wooden ones). In the vineyards, straight rows of grapevines, carefully staked and evenly spaced, replaced scattered bunches of sprawling vines. At the same time, the plants became much more homogeneous; whereas nineteenth-century growers deliberately mixed grape varieties, after phylloxera they often planted just one in their fields. In some parts of Hungary, well-known west European varieties (such as Merlot), became popular; in the Tokaj-Hegyalja region, growers doubled down on those most likely to produce quality wine (furmint, hárslevelű, sárga muskotály) and discarded unsuitable ones.

Not all changes were the direct result of phylloxera. The push toward standardization and science extended far beyond vineyards; this was an era in which Hungary adopted the metric system (in 1874) and Greenwich Mean Time (1893). The railroad would reach the village in 1909; to one enthusiastic journalist, this not only ended locals’ reliance on rutted roads (a “real torture”), but also brought visions of modernity and increased exports to the region.Footnote 54 Similarly, the greater use of artificial fertilizers, pesticides, and fungicides had its own momentum. For grape growers, the appearance of other menaces on their vines—downy mildew (peronospora), powdery mildew (oïdium), and grapevine cankers—made spraying an obligatory part of the agricultural cycle. These pests were treated with solutions of copper sulfate and slaked lime, called the Bordeaux mixture in recognition of its origins. By the early twentieth century, portable sprayers, with a hose and canister on the back, had become standard equipment in vineyards. Newspapers documented these changes, and in a typical advertisement, a Budapest dealer offered the “Triumph” back sprayer, the “Cyclone” hand sprayer, and the “Phylloxera injector” for carbon disulfide, along with a cloud-bursting cannon (Figure 2). New equipment and chemicals helped improve yields but created greater risks to the environment and public health. Increased chemical inputs nonetheless became a cornerstone of twentieth-century viticulture.

Figure 2: A 1901 advertisement aimed at beleaguered grape growers, with illustrations of a cloud-bursting cannon at the top, a “Phylloxera injector “in the bottom middle, and a variety of sprayers. Source: Borászati Lapok, 14 April 1901, p. 355.

For villages like Tállya, then, the promise of a “totally new, scientific viticulture” had ambiguous meanings. Most obviously, it meant the gradual reconstruction of its vineyards and the slow return to earlier levels of production. A bounteous harvest in 1901 did much to win over doubters. But the viticulture that emerged in the early twentieth century also meant agricultural experts, chemical sprayers, new tools, and greater expenditures. It strengthened the voices of experts who denigrated traditional skills and insisted that growers and winemakers learn from hefty manuals and traveling instructors. It gave the state a much greater role in the lives of men and women, even in a distant village like Tállya. For many Magyar elites, these dramatic changes were necessary and welcome, as well as a source of national pride. Surveying the region on the eve of World War I, one observer found ample evidence of “modern viticulture” (modern szőlőkultúra), proudly adding that “expert improvement of planting, cultivation, care, winemaking and cellar-management all proceed in an encouraging direction and, according to foreign authorities, the reconstructed grapes are first-rate in every respect.”Footnote 55 Closer to the ground, the neat, orderly rows of vines were a source of pride to many contemporaries: “regularity that enraptures the eyes,” enthused one.Footnote 56 Productivity, legibility, and simplification, the hallmarks of modern agriculture, had become defining features of Hungarian viticulture.Footnote 57

After the Storm

Phylloxera's impact on village life was as profound as it was on the surrounding vineyards. Contemplating the pest's destruction, wistful observers contrasted Tokaj-Hegyalja's grim present with what they described as its carefree, colorful past. In the words of one journalist: “So ended the abundance derived from rich harvests, so faded the vividness of popular customs and festivities in which this region had once gloried.”Footnote 58 Such portraits conveyed nostalgia for a past that never was. But they did capture something real. Winemaking villages in this region had developed characteristic features that set them apart from other settlements: a set calendar of work in the vineyards, a careful arrangement of local labor, a high degree of communal participation, and an agricultural cycle punctuated by festivals and processions. If we look closely at the upheaval around 1900, however, yet another picture emerges. Across Hungary, phylloxera put tremendous strain on local society and culture, and it soon became clear that the epidemic could produce anger and fear as much as wilted vines and empty wine cellars. In Tállya, the crisis revealed the fragility of social bonds, accelerated the transformation of popular culture, and attached a different set of meanings to wine.

The arrival of phylloxera quickly produced a siege mentality among village leaders, who looked with suspicion not just on plants but on people coming from outside. Among those affected were poor laborers who came to the village in search of work. Vineyard owners in the Tokaj-Hegyalja region had long relied on seasonal migrants, including many Slovaks and Rusyns from the northern parts of the Hungarian Kingdom, as well as on Magyars from surrounding counties.Footnote 59 At the height of the phylloxera crisis, however, the village council made it plain that poor workers who hoped to stay in Tállya were not welcome. In 1895, it affirmed that it would not grant legal residence or permission to settle to outsiders without documented means of support. Those lacking such means would be “expelled to their place of legal residence.”Footnote 60 The village was acting within its rights according to Hungarian law. But the message that outsiders were unwelcome was plain.

In this tense atmosphere, suspicion also fell on those who bought and sold wine. Wine merchants and brokers had always played an essential role in Tokaj-Hegyalja; peasants typically sold their grapes or wine soon after harvest, and only large landowners with their own cellars could afford to hold out until it was advantageous to sell. With the collapse of Hungarian production in the 1880s and 1890s, however, wine dealers had to scramble to keep stock in hand without bankrupting themselves. To make supplies last, less scrupulous merchants resorted to the time-honored tricks of the wine trade: watering it down, disguising bad batches with additives, or simply passing off poor stuff as quality wine. In response, the Hungarian government vainly attempted to crack down on adulteration and prevent wines from being sold under false labels. Other merchants began to sell Italian wine, which was legal, cheap, and abundant, thanks to the uneven progress of phylloxera in Italy and a favorable customs treaty signed between Austria-Hungary and Italy that went into effect in 1892.Footnote 61 In Tállya, all this came together in late 1901, when a county newspaper accused a respected local landowner and wine dealer named Norbert Lippóczy of fraud and, by extension, of ruining the good name of Hungarian wine.Footnote 62 In particular, it accused him of importing Italian wine, claiming it as the product of his Tállya vineyards, and selling it as liturgical wine in the Kingdom of Poland. Village leaders stoutly defended him, although they conceded that he had bought Italian wine, an unpopular action in the region. It is perhaps surprising that such charges were leveled against Lippóczy, a Roman Catholic of Polish descent, rather than against one of the region's many Jewish wine merchants, given that Jews were often linked to adulteration and fraud.Footnote 63 Lippóczy seems to have emerged unscathed from this episode. But the attacks on him again hint at the fraying of social relations and the strains of xenophobia caused by the phylloxera crisis. The resentment of imported wine likewise points to simmering anti-Italian views, which in Austria-Hungary would boil over during World War I.

The village had other problems closer to home. Even as reconstruction slowly advanced, prospects for its agricultural laborers and smallholders—the vast majority of the population—remained grim. Local day laborers faced erratic employment, depressed wages, and sometimes punishing conditions. Typical was an 1899 resolution passed by the Tállya village council, which required workers to be in the vineyards by 6:00 a.m. and levied strict fines on those who arrived late.Footnote 64 It did not help that the Ministry of Agriculture allowed towns and villages in the region to employ prisoners from locals jails in the vineyards (a role Russian POWs would play during the war). Owners of small plots of land also struggled. A clear-sighted contemporary observer, Irén Spotkovszky, noted that although phylloxera had indiscriminately ruined most growers’ vineyards, sparing neither the rich nor the poor, large landowners had reaped the lion's share of rewards since the reconstruction of Tokaj-Hegyalja's vineyards had begun.Footnote 65 Many smallholders, in contrast, had been “strongly adverse to replanting,” a resistance she blamed on stubbornness and ignorance. But she also recognized that for those with smaller plots, “planting and cultivation are expensive, and investment is difficult in the absence of capital.” Just where this capital might come from or how the benefits of reconstruction could be enjoyed by all was not explained. Instead, Spotkovszky—like nearly all writers on this topic—placed her faith in continued education, improved methods, greater exports, and “continuous developments in oenology.”

Over the long term, these factors would fundamentally alter the production of Hungarian wine. For now, the promise of increased education and exports offered little recompense to the more precarious growers and laborers in the region. In the years around 1900, young people voted with their feet and left the region for Budapest or America. Precise numbers on migration are hard to come by, although anecdotal evidence provides some support for fears about emigration. In lists of military recruits, for example, “Amerika” is scrawled next to young men's names.Footnote 66 The village's population remained virtually unchanged between 1880 and 1910, decades when the population of Hungary as a whole grew by more than 30 percent. And fears often outran the figures. Writing in 1906, Tállya's Calvinist minister and vineyard owner Emil Hézser warned that an “emigration fever” had struck the region.Footnote 67 Stressing its economic causes, Hézser pointed to the relatively high cost of living and low wine prices. He admitted that reconstruction had not gone smoothly and that many new vines were ailing, which he blamed on drought, mistakes in planting, improper manuring, and imprecise application of fungicides. This was typical: leaders like Hézser were aware that structural economic conditions (including a growing glut of wine on world markets) worked against many Hungarian growers, but he was also quick to blame those same growers for their lack of skill and knowledge. Hézser was not alone in worrying about emigration. A Budapest newspaper reported in 1907 that migration from Tállya continued to surge, in spite of improved local wages.Footnote 68 Such reports only strengthened fears among elites that laboring people were not content with existing conditions and that winemaking regions would suffer as a result. Hungarian migrants were not like their French counterparts, who took grape cultivation and winemaking with them to coastal Algeria, soon a major wine producer in the mid-twentieth century. Those who left Hungary typically went to work in American mills and mines, leaving behind their knowledge and experience.Footnote 69

Those who remained in villages like Tállya acquired new skills but employed them in a very different context. Overlooking the hard times and lean years of the 1800s, many writers have emphasized what was lost in this transformation. According to the local historian Péter Takács, phylloxera snapped “decades-old ties of friendship, as well as economic, commercial, and neighborly relations.”Footnote 70 In this telling, village customs slowly fell into disuse, the fiddles fell silent, the processions stopped. Contemporaries glumly noted that high-proof brandy (pálinka) replaced wine at festivals and dances, leading a local doctor to complain indignantly to the Tállya village council that “young men—alone, in pairs, and in groups—confused in their wits by the excessive use of liquor, roar in unseemly animal voices (often obscene) songs as they roam along the main street, often hindering pedestrian and carriage traffic and scandalizing the street's residents and sometimes insulting sober citizens returning from work.”Footnote 71 The geographer Spotkovszky took a more measured view of this change. The younger generation of villagers in this region, she wrote, knew “the merry Hungarian harvests” only by reputation: “The good old world has disappeared and harvest has become serious, all-important business, in which a grower's labor for the entire year and invested capital are at stake.”Footnote 72 Such observations tell a story in which the age-old, patriarchal world was giving way to more rational, impersonal, capitalist activity.

In Tállya and places like it, a distinctive way of life had grown up around grape cultivation and winemaking. But just as plants and vineyards changed in the wake of phylloxera, village life changed as well. Buffeted by global economic forces and weakened by emigration, village customs and practices that had helped turn wine into a national symbol were disappearing. Across Hungary, peasants readily traded their homespun cloth for factory-made clothes and landowners placed their hopes in more capital-intensive agriculture. We should be wary of overstating the speed or completeness of this transformation. Nor should we romanticize the world that was lost. This case study instead underscores two features of these changes. The first is their rapidity: in little more than a decade, the crisis brought on by phylloxera upended people's lives and livelihoods across the Tokaj-Hegyalja region, meaningfully altering their likelihood of staying put, relations with their neighbors, and approach to the market. The second is how phylloxera accomplished what many Magyar elites had long wanted: a thorough reorganization of the Hungarian wine sector. Writing in 1875, Keleti had dreamed that rational changes could lead Hungary's wine regions to produce “uniform wines with a defined character and unvarying quality.”Footnote 73 Even Keleti could not have imagined that this goal would be achieved through a tiny insect and the global catastrophe it caused.

Conclusion

In Bram Stoker's Dracula, the sharp-toothed count serves his guest “some cheese and a salad and a bottle of old Tokay.”Footnote 74 Tokaj had long been famous, and Stoker's book appeared in 1897, near the end of a century in which an army of officials, journalists, experts, and poets had helped secure wine's place in the pantheon of Hungarian national symbols. Like nationalists everywhere, they left out much in the stories they told about wine, romanticizing or largely ignoring the conditions under which it was made.Footnote 75 Profits mattered to them—the creators of the Tokay Album, for example, cared greatly about exports—but they also wanted wine to promote national cohesion, shape Hungary's image abroad, and demonstrate Hungary's modernity.Footnote 76 When Magyar elites did turn their attention to production, they cheered the introduction of a more scientific, modern agriculture, which was given an unexpected boost by the phylloxera crisis. Much of what I have analyzed here recalls the “high modernist” transformation of many rural areas as described by Wendell Berry, James Scott, and others. Twentieth-century agricultural experts and planners invariably preferred monocultures and machines; emphasized legibility and simplification; and denigrated local knowledge and skills. The outcomes of their projects were mixed and included high human and environmental costs.

But the success of Tokaj-Hegyalja's wine and its place as a national symbol had been secured, a point driven home in recent decades. In 2002, UNESCO named the Tokaj region a World Heritage Site (since converted to a Historic Cultural Landscape). This recognized the region's long history of winemaking, emphasizing its aszú wine, its “rich and diverse cultural heritage,” and its hopes for sustainable development.Footnote 77 A decade later, aszú wine produced in Tokaj-Hegyalja was named a Hungarian specialty (hungarikum), a category created by a 2012 law establishing an “appropriate legal framework for the identification, collection and documentation of national values for the Hungarian people and by this providing an opportunity for making them available to the widest possible audience and for their safeguarding and protection.”Footnote 78 The authors of the Tokay Album would likely have recognized and welcomed this goal. More certain is that gastronomy and wine are increasingly visible today in Hungarian tourism, official definitions of culture, and nationalist politics of identity.Footnote 79

Wine's prominence has not always translated into ready gains for villages like Tállya. This study has focused on phylloxera and the wider crisis around 1900 as a pivotal moment in the history of the village and its vineyards. In the years that followed, the hammer blows of history continued to fall. Some misfortunes could be undone: when Romanian soldiers occupied the village in 1919, at the conclusion of World War I, they requisitioned more than sixty-five thousand liters of wine from its cellars. Others could not: in 1944, more than 170 Jews were taken from the village and deported to Auschwitz, abruptly and tragically ending centuries of Jewish life in Tállya. After World War II, grape cultivation and winemaking lost their leading role as villagers took jobs in a new quarry and a factory in a neighboring village. Declaring that the “entire Tokaj-Hegyalja is … antiquated,” communist planners in the 1950s implemented sweeping changes that favored quantity over quality and consequently expanded vineyards on the lowlands, where growers could drive Soviet tractors between rows of vines.Footnote 80 Later decades of communism showed more imagination and some specialization. But after 1989 the tractors were sold, the quarry abandoned, and the factory shuttered. Multinational wine companies, many of them French, swooped in and bought up prime vineyards in Tokaj-Hegyalja. But investors and employers have been scarce in Tállya; its population has continued to fall, and today it's just half of what it was in 1960 (or 1860, for that matter). This will come as no surprise to anyone familiar with rural Hungary. Periods of relative stability and prosperity have been the exception over the past 150 years. For Tállya, one might point to the last years before World War I, to the upturn of the late 1920s, and to the 1970s and 80s, when the Hungarian state actively supported rural economic activity. But a lack of investment, out-migration, and unforgiving global economic forces have too often been the rule.

Yet today, looking carefully, one can see other traces of the village's long history of viticulture. Studying maps from the 1700s and cadastral records, one local winemaker has identified, purchased, and replanted parcels that had once produced great wines but in recent decades had not, in spite of the heavy use of insecticides and fertilizer.Footnote 81 Elsewhere the vineyards have crept back up the hills, reclaiming soil that had produced grapes for centuries. Cellars from the eighteenth century remain in use. In them, blending global norms and local expertise, the village's growers produce a range of white wines, some of them excellent. Wine in this region has a deep history; one can only hope that it will have a long future as well.

Acknowledgements

Colgate University funded the research for this project, which was first presented at the 2019 ASEEES conference in San Francisco. For their comments and suggestions at the panel and on later drafts, I am grateful to Andrew Behrendt, Mary Neuburger, Alison Orton, Kristina Poznan, Kira Stevens, Alexander Vari, and the two anonymous reviewers of the journal. I would especially like to thank the staff of the Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County Archives in Sátoraljaújhely—and especially head archivist Tamás Oláh—for their generosity and assistance.