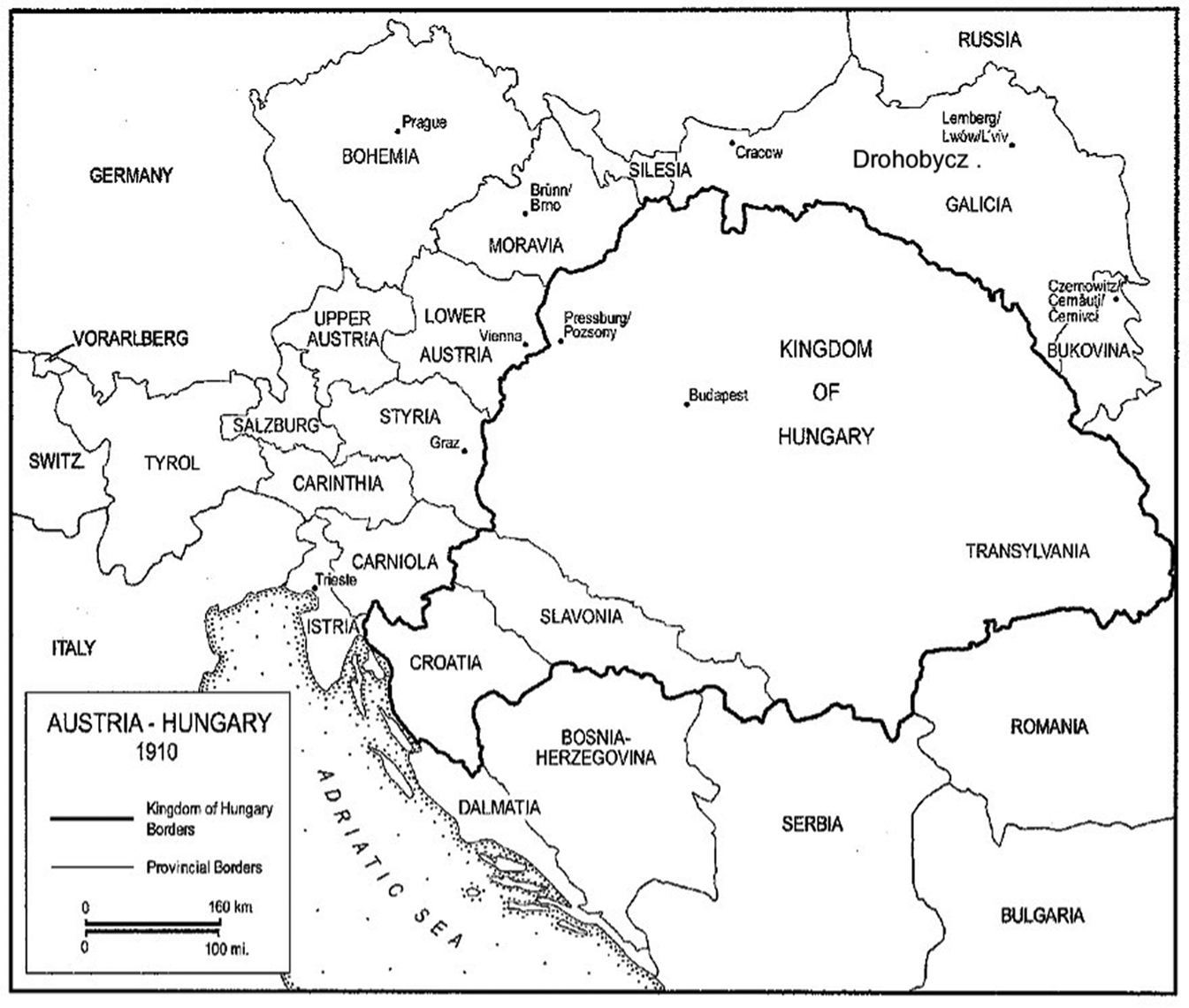

On 19 June 1911, Austrian military forces in Drohobycz, East Galicia, protecting the city's sole polling station for parliamentary elections opened fire on a group of unarmed citizens (Figure 1). Twenty-six people were killed instantly, including women, children, and elderly, and within days fourteen more died of their wounds. Dozens more were left maimed. This extraordinary violence by the state against its own citizens shocked Austrian and foreign public opinion. Rarely noted by the non-Jewish press, however—which covered the massacre extensively—was its ostensibly Jewish character.

Figure 1. Map of Austria-Hungary, 1910. In Pieter M. Judson and Marsha L. Rozenblit, Constructing Nationalities in East Central Europe (New York, 2005).

The election—Austria's second with universal male suffrage—was being rigged in favor of the Jewish candidate of the conservative Polish faction, Nathan Löwenstein, by another Jew, Jacob Feuerstein, the city's most powerful politician. Löwenstein's principal opponent was the Zionist candidate Gershon Zipper, whom he had previously defeated by chicanery in 1907. In other words, a Jewish oligarch directed the bureaucratic and military arms of the Austrian state to contrive the election of one Jewish candidate, representing a Polish nationalist position, over another, representing a Zionist one.

As such, this case deserves scrutiny not only to understand how this early experiment in democratic reform failed but equally as a moment that illuminates the limits of nationalism and national identity in this seemingly hypernationalized political environment. It demonstrates the process by which a local interethnic oligarchy adapts to a democratic age to maintain its power and the role that violence plays in that transformation. Drohobycz exemplifies what Larry Diamond labeled an “authoritarian enclave” in a developing democracy, a place where decentralized power—particularly over security forces—means that democratization paradoxically entrenches the power of local “political bosses.”Footnote 1 This is particularly true when those bosses are doubly empowered by provincial and/or central authorities who defend their rule in exchange for the delivery of reliable, conservative men to the representative bodies.Footnote 2

This case study thus serves as evidence of this phenomenon in Austria, situating (and normalizing) the Habsburg experience in this broader framework. Moreover, as noted elsewhere in this volume, it was not the only electoral violence during Austria's transition to democracy, although it was by far the most extreme and well-covered case.Footnote 3 Thus, examining the role of the imperial, provincial, and municipal authorities in administering the newly democratic elections and then responding to the massacre sheds light on the relationship of an imperial center to a rapidly modernizing provincial city on the periphery during this period of democratic change. Equally, comparing competing narratives of the massacre not only elucidates its actual course and causes but also highlights how competing political factions constructed their identities around it, exposing the role of nationalism and national indifference in this modern political event.

Since the 1880s, amidst a broader struggle between Polish and Ukrainian nationalists in Galicia, a small but robust Jewish nationalist movement emerged. Although often calling themselves “Zionists,” Jewish nationalists in Galicia generally viewed a Jewish home in Palestine as a distant dream and focused instead on convincing both the state and the Jews that they too constituted a national community, one deserving the same rights promised to other national minorities by Austria's 1867 constitution. Their principal Jewish opponents were self-described assimilationists who argued that Jews constituted a religious community only. This conflict manifested not only in rival journals and organizations but also in the political arena, as Zionists increasingly sought to replace assimilationist leaders at all levels of government and ultimately to democratize their elections.Footnote 4 Conservative Poles naturally supported the assimilationists, while Ukrainian nationalists tended to support the Zionists in their effort to undermine Polish hegemony.

Zionists and assimilationists, as well as Polish and Ukrainian nationalists, portrayed the election and massacre as a national struggle and used it in constructing their respective identities. In reality, these narratives concealed a populist uprising against an adaptive, local oligarchy supported by the state and its political and military agencies. The alliance of Polish and Jewish elites that ran the city faced opposition from a groundswell of voters—Jewish, Ukrainian, and Polish—supporting multiple candidates attempting to unseat the district's traditional rulers. Most Jews, for example, were not committed nationalists but had grown loosely sympathetic to the notion of Jewish nationhood and, inspired by the democratic Zeitgeist, supported Jewish nationalist candidates replacing pro-Polish oligarchs.Footnote 5 In other words, this event being narrativized as an internal Jewish conflict between Zionists and assimilationists or a national conflict between Poles and Ukrainians was really about local power and politics—the people against a local oligarchy—not the national oppression of Ukrainians and Jews by Poles, or of Zionists by assimilationists.

The story thus questions the extent of the role nationalism plays in violent political conflict, even in a seemingly hypernationalized environment, and demonstrates how nationalist rhetoric masks other motivations of historical actors. This microhistory builds on recent efforts to locate national indifference in the modern period, in the eye of the nationalist storm. It supports Rogers Brubaker's preference for more multilayered notions of self-identification and loyalty and Tara Zahra's exposure of “national indifference as a category of analysis.”Footnote 6 At the same time, the success of nationalist actors—especially the subaltern Jews and Ukrainians—to reframe this event in nationalist terms demonstrates how nationalism could shape historical memory and successfully push back against this indifference. This essay will for the first time explicate the history and memory of this remarkable event while challenging the nationalist narratives that successfully shaped collective memory in its aftermath.Footnote 7 The massacre demonstrates that nationalization was a gradual process, during which other identities persisted and other factors guided political events, while exposing how nationalist leaders paradoxically used such moments to obfuscate this reality and advance their own agendas.

Drohobycz, Galicia

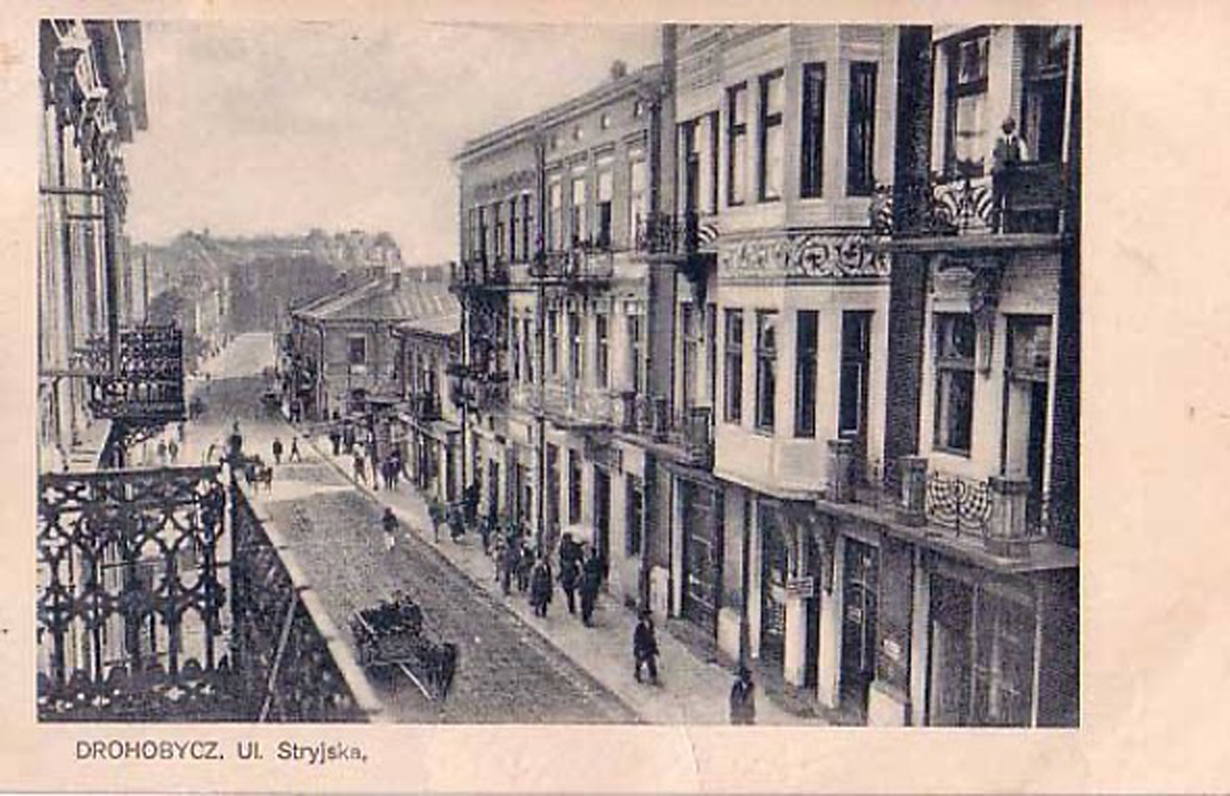

Galicia was the largest of Austria's provinces. Its nearly 900,000 Jews in 1910 constituted about 11 percent of the region but three-quarters of Austrian Jewry overall.Footnote 8 Galicia's remaining population was divided evenly between two other ethnolinguistic groups, Poles and Ukrainians, the latter overwhelmingly concentrated in the eastern part of the province. Although small, Drohobycz was an important Galician city in 1911, particularly for Jews (Figure 2). Drohobycz numbered 15,313 Jews in 1910, about 44 percent of the city's population, while Jews constituted 17 percent of the whole political district, the third-highest percentage in Galicia after Kolomea and Stanislau.Footnote 9 Drohobycz had been transformed in the mid-nineteenth century by the discovery of oil in nearby Boryslaw and by new methods of its refinement, which by the turn of the century had turned Galicia into the third-highest producer of oil in the world, after Russia and the United States (Figure 3).Footnote 10 The new oil industry, in which Jews at first played a dominant role as both developers and workers, made Drohobycz a more prosperous and cosmopolitan city than most other Galician Jewish communities.Footnote 11 Drohobycz, the third-wealthiest city in Galicia after Lemberg and Cracow, served as the “living quarters” of the wealthy Jews who owned oil fields in the surrounding area and who generously funded the local Jewish community and its institutions, which they controlled tightly.Footnote 12 These families generally identified with Polish political elites and culture, while most Jews in the region remained religiously traditional, Yiddish-speaking, and poor (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Drohobycz in a contemporary postcard.

Figure 3. The Boryslaw oil fields. Source: Drohobycz, Boryslaw and Vicinity, “Black Gold!,” https://www.drohobycz-boryslaw.org/en/drohobycz-boryslaw-and-vicinity/oil.

Figure 4. Postcard depicting a less fashionable neighborhood of Drohobycz. Source: Reunion68, http://www.reunion68.se/?p=67622.

Drohobycz politics reflected broader Galician trends. Beginning in 1867, in exchange for their support of the crown (the conservative parliamentary faction known as the Polish Club kept many Austrian cabinets in power), Polish elites enjoyed virtual autonomy in Galicia, dominating the provincial diet and monopolizing administrative power.Footnote 13 The ruling Poles launched an intensive Polonization campaign, claiming a demographic majority over the Ukrainians by counting the Jews as Poles in the decennial census, which did not recognize Yiddish as a language and therefore Jews as a national group. As Galicia Polonized, so too did its Jewish intellectual and economic elite. Polish replaced German as the language of the secular Jewish youth, and by 1879 Jewish representatives in the Imperial Parliament (Reichsrat) nearly all joined the Polish Club. Polish and Jewish elites forged an agreement for provincial elections whereby the former would support the election of pro-Polish Jews in Lemberg, Cracow, Stryj, Brody, Kolomea, and Drohobycz in exchange for Jewish support of Polish candidates in rural districts.Footnote 14

In Drohobycz, as in other Galician cities, Jewish economic elites united with Polish politicians in dominating local politics. As Yevhen Polyakov has demonstrated, ethnic divisions between Catholic Polish and Jewish communities were far less important than the separation of the socioeconomic elites from the masses. For several decades, Drohobycz by design had a Catholic Polish mayor and a Jewish vice mayor, including Feuerstein from 1900 to 1908, who together ran the city.Footnote 15 Zionists established their first association in Drohobycz by 1887, and others followed, but the movement remained mostly limited to members of the secular intelligentsia, itself culturally Polonized even as it insisted in Polish-language papers and speeches on the existence of a Jewish nation.Footnote 16

Although American-style rules of entrepreneurship allowing individuals to exploit their own property without government interference at first enabled incredible opportunity for overnight wealth, by the end of the century oil production was concentrated into the hands of a small number of major firms.Footnote 17 Other Galician towns had Polish–Jewish oligarchies.Footnote 18 In Drohobycz, however, oil wealth not only defined the elite but it also ramified its power and its connection to the central authorities. Viennese protection of domestic owners against foreign competition, government efforts to consume the glut of oil that flooded the market in the early twentieth century, and military support against striking workers, combined with the greater wealth of this elite in comparison with their counterparts in other Galician cities, had the effect of amplifying local power and strengthening its ties to Vienna.Footnote 19 Drohobycz was an extreme example of an otherwise widespread phenomenon.

The most powerful of the oil moguls in fin-de-siècle Drohobycz was Jacob Feuerstein (1866–1927; Figure 5). Feuerstein was the nephew and son-in-law of the oil magnate Lazar Gartenberg (1833–98), who along with his brother Moses had built a fortune in oil holdings and refineries in the region. By the early twentieth century, Feuerstein dominated the local oil industry and had amassed incredible wealth and several estates.Footnote 20 Feuerstein's father, Elias, served as head of the Jewish community, a position also held by Jacob in addition to the post of vice mayor. Feuerstein was widely regarded as the most powerful man in the city, which in 1907 renamed its “most beautiful” street after him (Figure 6).Footnote 21

Figure 5. Jacob Feuerstein. Source: Drohobycz Administrative District, “The Vice-Mayor of Drohobycz—Jakob Feuerstein and his Family,” kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/drohobycz/families/jacob-feuerstein-family.html.

Figure 6. Postcard depicting Jacob Feuerstein Street. Source: Drohobycz Administrative District, “The Vice-Mayor of Drohobycz—Jakob Feuerstein and his Family,” kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/drohobycz/families/jacob-feuerstein-family.html.

Feuerstein was a complicated figure: an effective leader but power hungry and corrupt. Some sources portrayed him quite sympathetically, emphasizing how he almost single-handedly developed Drohobycz into a modern city and insisting that as head of the Jewish community he cared deeply about local Jews. His defenders included his grandson Jacques Benbassat, who acknowledged his grandfather's steadfast support for the “interests of the wealthy Polish nobility and industrialists in Galicia,” but even some of his Zionist opponents admitted his contributions.Footnote 22 Shimon Lustig, a local Zionist leader whose brother was killed in the massacre, described Feuerstein as a very wealthy man “without enlightenment” who nevertheless “possessed a good heart” and frequently helped constituents by intervening with the authorities. Julian Hirshaut, whose chronicle of Drohobycz eviscerates Feuerstein for his corruption and “venomous” destruction of his political enemies, confessed he even bailed out poor Jews arrested for inscribing Yiddish as umgangssprache on the 1910 census, a Zionist campaignFootnote 23 opposed by pro-Polish Jews like Feuerstein.Footnote 24

Most memoirs of Drohobycz, however, and certainly most contemporary accounts, depict Feuerstein in far more negative terms, describing him as a man prepared to do anything to keep his grasp on power.

“He was a man of iron will,” wrote Shmuel Rothenberg, “who did not surrender to pressure or resistance from any side. He alone ruled the city. He appointed the mayors, the city council members, the community board members, the rabbis, and to a large extent approved the appointment of the city's priests, who were named based on his recommendation. He eliminated his political opponents by any means.” Rothenberg claimed he wasn't even a principled Polish nationalist. At a city council meeting in 1907, when the high school principal expressed his opposition to one of Feuerstein's proposals, Feuerstein allegedly replied, “You Poles, what do you have here? Take your churches and your sokol auditorium and go to hell.”Footnote 25 A Zionist report of the massacre similarly described Feuerstein's support of assimilationism as insincere cover for his singular goal of maintaining his power in the city.Footnote 26

Countless others of every ethnicity described his unbridled power similarly. David Horowitz called “Yankel” Feuerstein “the little dictator” who ruled without limits at the top of a corrupt pyramid of power that controlled the entire bureaucratic infrastructure of the city as well as its underworld.Footnote 27 Nathan Birnbaum called him the “absolute ruler” of Drohobycz.Footnote 28 For the Ukrainian Social Democrat Semen Wityk he reigned as “absolute monarch,” while the Polish Socialist leader Herman Diamand described all local government as extensions of a “mafia ruled by his majesty, Lord Jacob Feuerstein I.”Footnote 29 Drohobycz, concluded the progressive Polish representative Ernst Breiter, was a “government recognized domain of the family Feuerstein,” which appointed every government employee from the mayor to the tax assessors and judges, and reaped “millions” from this power.Footnote 30

Parliamentary Elections in a Democratic Age

Feuerstein's power achieved much broader significance in 1907, when Austria elected its first Imperial Parliament based on universal male suffrage. To alleviate nationalist tensions, which had paralyzed legislative activity, districts were supposed to be as nationally homogeneous as possible. This meant that not all districts would represent an equal number of constituents. In Galicia, for example, Ukrainian districts included almost double the number of voters as their Polish counterparts. Moreover, Parliament instituted a minority protection system in Galicia to inflate Polish rural representation while neutralizing Ukrainian and Jewish urban minorities, protecting the powerful Polish Club from losing too much control.Footnote 31

Nevertheless, conservative Poles faced new political threats from progressive and nationalist Polish parties, Social Democrats, Ukrainians, and Zionists.Footnote 32 Despite the rigged system, all these factions hoped to gain seats at the expense of the Polish Club and thereby to effect greater democratic change in the province and empire. In a handful of major Jewish urban centers, such as Brody, Kolomea, Tarnopol, Buczacz, and Drohobycz, the Polish Club relied on its Jewish allies to defeat these forces.

Galician Zionism had always been a Diaspora-oriented movement, focused on nationalizing Jewish identity and securing Jewish national rights in Austria, and Jewish nationalists in both Galicia and Vienna saw this election as their most important opportunity. Replacing Polish Club Jews with their own candidates would give them a platform in the Reichsrat to advocate for the recognition of Jewish nationhood and the democratization of communal elections, their two immediate goals, and would significantly boost the prestige of the movement overall. Austrian Zionists ran candidates in two dozen districts, mostly in Galicia. The election pitted an alliance of Jewish nationalists and Ukrainian National Democrats against the Polish Club, represented in predominantly Jewish districts by wealthy, Polonized Jews. Despite extensive electoral corruption, they managed to elect four Jewish nationalists to the Reichsrat, two directly (including the powerful boss of Czernowitz, Benno Straucher) and two with Ukrainian votes from rural east Galician districts. The four constituted the self-proclaimed “Jewish Club,” the first Jewish national parliamentary faction in history.Footnote 33 Other candidates fell to criminal tactics known throughout the empire as “Galician elections.”

First coined in 1895 to describe fraudulent elections to the Galician Diet, the term “Galician elections” quickly became a catchphrase in Austria for blatant electoral chicanery.Footnote 34 The degree of corruption, terror, and intimidation employed to defeat opponents of the Polish conservative candidates to Parliament in 1907 surpassed anything that came before it. Jews were particularly sensitive to government intimidation. Many segments of Jewish society—merchants, shopkeepers, inn keepers, and artisans—were dependent on the magistrate, the state bank, the police, and other state institutions and could not risk their retribution.Footnote 35 Polish conservatives and their Jewish allies—who must also be considered Polish conservatives—used these tactics not only against Zionists but equally against Ukrainian, socialist, and Polish opposition. Where voters disregarded the threats, municipal authorities—safely in Polish hands—simply falsified the results or openly annulled the offending votes. More seriously, there were widespread documented reports of garrison forces keeping Jews and Ukrainians out of the voting booth, while others voted multiple times, and of supporters of the opposition being arrested on no grounds.Footnote 36

In Drohobycz, Feuerstein flexed all his administrative and political muscles in 1907 to ensure the election of his candidate, Nathan Löwenstein (1859–1929), a longtime advocate of Jewish Polonization and leader of the pro-Polish “Jewish Electoral Organization” (Figure 7).Footnote 37 This reflected the traditional alliance of Jewish oligarchs and conservative Poles in Drohobycz and throughout Galicia, which assured Feuerstein's control of the city in return for delivering the Polish conservative candidate to parliament. For example, municipal tax authorities compelled nearly every Jew with any debt or city code violation to pay immediately, or else to sell his wares at a loss to raise the money, while Feuerstein promised to save anyone who agreed not to vote for the Zionist Gershon Zipper (1868–1921; Figure 8).Footnote 38 His tactics proved successful, and Löwenstein was elected despite widespread popular support for both Zipper and the Socialist candidate, Samuel Häcker.

Figure 7. Nathan Löwenstein. Photo published in J. Kreppel, Juden und Judentum von heute (Zürich, 1925), 224–25. Source: iPSB, https://www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl/a/foto/natan-loewenstein.

Figure 8. Gershon Zipper.

Feuerstein fully intended to repeat this performance in 1911. In the interim, however, his task had become more difficult. Jewish national sentiment and democratic attitudes had grown considerably over those four years, and many Zionists, socialists, and other radicals too young to vote in 1907 had now come of age and would not be easily bought.Footnote 39 Feuerstein may have discovered this sea change on 21 April, when Zionists and others swarmed a Löwenstein rally with two thousand supporters whose continuous booing eventually led the gendarmes to break up the meeting altogether. Just before ordering the dissolution, Feuerstein openly declared that he would personally elect Löwenstein regardless of popular will. “And if you all do not want him,” he allegedly shouted, “I'll know how to impose his re-election!” With these words, declared Moritz Pachtman (chairman of the joint opposition electoral committee), Feuerstein launched “the most corrupt election campaign yet to be seen in Galicia.”Footnote 40

That Zipper enjoyed widespread support was not Zionist fantasy. Thousands turned out at his rallies, for example, in a district with just six to seven thousand voters.Footnote 41 Zipper's coalition (unlike most Zionists in 1911) included many Ukrainians, despite the presence of an alternative Ukrainian candidate, Volodymyr Kobryn.Footnote 42 (Mateusz Balicki represented the Polish National Democrats but was put up by Jewish oil rivals of Feuerstein, again complicating the nationalist narratives.Footnote 43) Zipper even enjoyed the backing of a local rabbi, Chaim Meir Yechiel Shapira, who preached on Zipper's behalf and allowed him to hold rallies at his private synagogue. Rivka Shapira recalled “the entire young generation” welcoming Zipper when his train pulled into the city, running down the street shouting that the Messiah had arrived.Footnote 44

In 1911, Feuerstein added new measures to the tactics described in the preceding text. For example, his ally Mikołaj Kiedacz, the secretary of the magistrate, added 1,400 names to the voter rolls at the last moment, swelling the list by more than 50 percent in just four years. Breiter accused Feuerstein of personally composing over a thousand registrations and implied that Löwenstein was equally culpable. Zionists and Social Democrats alike—united in their effort to unseat the ruling clique—accused authorities of inserting dead, nonexistent, absent, underage, or female names, noting that the city illegally prevented them from seeing a separate list of the added names and kept the complete list of names out of alphabetical order to obfuscate the fraud.Footnote 45 Kiedacz forbade anyone from copying names off the list and only made copies available (at a very steep price) one week before the deadline to challenge it.

The magistrate refused to issue any residence certifications, while the Jewish community board (Kahal) colluded with him by refusing to issue birth, wedding, or death certificates of Jews. In this way, Feuerstein converted his control of the Jewish community into power over the entire district. Opposition parties eventually counted 600 nonexisting people, several dozen dead, 350 registered twice, 20 underage boys, many convicts, numerous women, and 80 people not living in Drohobycz. They quickly brought their complaint to the Interior Ministry in Vienna, which struck down more than half of the new names. But local power outweighed distant imperial decrees: the ministry ordered the municipal authorities to remove the names from the roles, an order it dutifully obeyed just after the election.

Distribution of the ballots was likewise obstructed. Many voters faced insurmountable hurdles to get their ballots, including a trip to the Kahal building (again, well-integrated into municipal governance toward this illicit purpose) where they were grilled about personal details until a discrepancy was found in the documentation, giving grounds to deny the card.Footnote 46 Meanwhile, Feuerstein's family and friends picked up ballots for tenants and employees, who were coerced to sign their receipt without receiving the cards.Footnote 47 The Kahal building was turned into an inn, filled every day with beer and food. There the vice president of the Jewish community, Markus Sternbach, directed a team of “hyenas” to purchase or steal ballots already delivered. Finally, the principal of the local gymnasium threatened parents that he would bully their children unless their identity cards and ballots were turned in to Feuerstein, as head of the Jewish community, for their “protection.” The principal, a well-known antisemite, headed Löwenstein's election committee, once again demonstrating that the battle lines had little to do with national strife but rather exposed an interethnic, Polish–Jewish elite that was ensuring its own political survival.Footnote 48

On election day, Feuerstein set up just one polling station for eight thousand voters, compared to two stations in 1907 for five thousand. The room was filled with several hundred “civil guards” specially empowered for the occasion, allegedly from violent criminal elements (Figure 9). They terrorized voters, blocked access to the urn, ripped ballots out of hands, and distributed stolen ballots into hands that would safely stuff the box for Löwenstein.Footnote 49 If a voter got past them, members of the election committee sitting next to the ballot box had another chance to prevent an opposition vote from being cast. Election monitors from the opposition parties were barred from the site.Footnote 50

Figure 9. “Citizen Guard” pass (“to maintain peace and calm during the elections”), signed and stamped by the district commissioner. Prawda o wyborach drohobyckich odbytych dnia 19. czerwca 1911. r. (Lwów, 1911), 24.

Election Day

All these tensions came to a head on election day. What exactly happened on 19 June was hotly debated. Contradictory reports appeared in dozens of newspapers, scores of correspondences, eyewitness testimonies, four days of parliamentary debate, and a forty-page Zionist booklet published just months afterward. Nevertheless, a careful compilation of all this evidence, together with memoirs and archival sources, paints a reasonably coherent picture of the day's events.

Voting at Drohobycz's only polling station opened at 5:00 a.m. Large crowds of people soon gathered outside the station, the town's old theater, which limited admittance through a single entrance—also serving as the exit—mostly to a small number of reliable Löwenstein supportersFootnote 51 (Figures 10 and 11). Following an effort to rush the door at 7:00 a.m., mounted police drove the crowd back to Stryjska Street, a narrow road leading from the theater to the Ringplatz, or market square (Figure 12). By 8:00 a.m., several thousand people had gathered in the rain, packing the entire area from the theater to the Ringplatz, about one hundred meters away (Figure 13). Men with a note from Feuerstein, many allegedly outsiders with stolen or forged ballots, were admitted through the side door without delay, but virtually no others.Footnote 52 By 9:00 a.m., garrison forces from Stryj and Rzeszów, as well as a company of mounted police, had joined local police to protect the theater.Footnote 53

Figure 10. The polling station/theater. Das Interessante Blatt, 29 June 1911, p. 3. Source: ANNO, Austrian National Library.

Figure 11. The street space in front of the theater. Photo: author.

Figure 12. Stryjska Street, viewed from the Ringplatz. The theater is at the back on the right side. Source: https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Історія_Дрогобича.

Figure 13. Postcard depicting the Ringplatz. Source: My Shtetl: Jewish Towns of Ukraine, http://myshtetl.org/lvovskaja/drohobych_en.html.

By 11:00 or 11:30 a.m., with the station still closed to nearly all voters, the mob grew violent, allegedly taunted by Noe Szauder, who flaunted a pack of ballots from inside the office, and Leib Rosenschein, who shouted: “They will go and vote as often as they like, and you will stand here and wait and you will not get to vote!”Footnote 54 The mounted police herded the crowd into Smolka Square but were attacked with sticks and rocks and retreated as the mob started rampaging at the Ringplatz, breaking windows and destroying public and at least two private buildings: Löwenstein's campaign headquarters and Feuerstein's home. That attack was apparently sparked by a stream of Feuerstein employees and nonresidents entering Löwenstein's headquarters every few minutes to get passes and ballots.Footnote 55

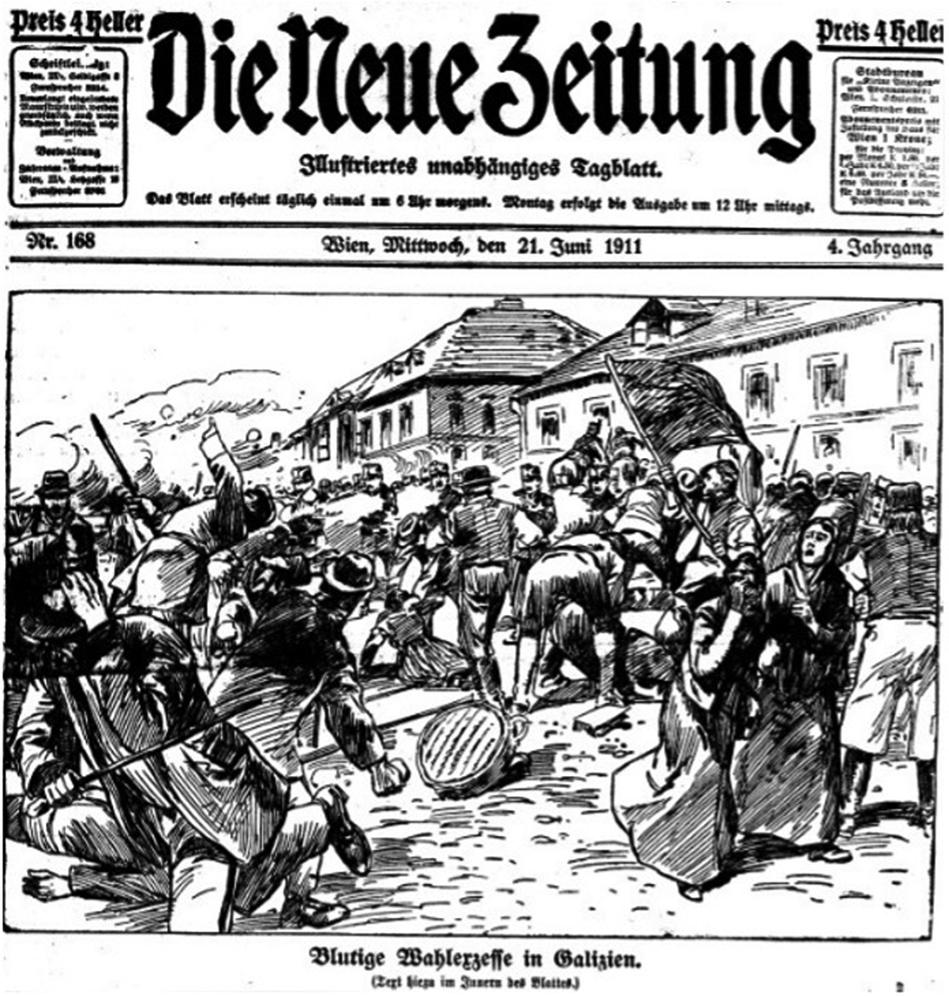

At 1:00 p.m., as violence began to subside, the city declared a midday break in voting—a violation of electoral law that Zionists charged was designed to give Feuerstein time to recompose the destroyed ballots—and closed the station entirely until 3:00 p.m. The crowd exploded in one last rampage, smashing the windows at the Kahal building and Feuerstein's home. Then it dispersed. Various people started to return around 2:00 p.m., including women and children, mostly to gawk at the damage or else simply to pass through. Just after 2:00 p.m., some men again broke into Löwenstein's campaign office and started throwing out broken chairs, but they quickly escaped. Then, at 3:30, a squadron of forty men from Rzeszów fired five rounds, ninety-four shots, on the crowd and attacked the fleeing survivors with bayonets (Figures 14 and 15).Footnote 56

Figure 14. “Bloody election violence in Galicia.” Front page of Die Neue Zeitung, 21 June 1911. Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library.

Figure 15. Illustration depicting the election violence in Drohobycz. Das Interessante Blatt, 29 June 1911, p. 3. Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library.

News of the massacre spread quickly throughout Austria and reached international proportions (Figures 16 and 17). “Austrian Election Riots, Military Kills Eight Persons” declared The Dominion in New Zealand. “Election Riot, Terrible Scene in Galicia” reported the Straight Times in Singapore, while The Times in London headlined, “The Austrian General Election: Fatal Riot in Galicia.” And papers across the United States, from Fort Wayne to New Orleans, from Albuquerque to Boston and many places in between expressed shock at the violence.Footnote 57 Within Austria, news of the massacre dominated election coverage, rivaling even the bigger story of the Christian Socialist setback.

Figure 16. “Bloody Elections in Drohobycz.” Front page of Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny, 22 June 1911. Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library.

Figure 17. Front page of Jüdische Illustriete Zeitung, 30 June 1911. Upper: “Bloody Elections in Drohobycz.” Lower: “The horrible scene, when the military suddenly shot at the street crowd.”

What triggered the massacre? Initial reports, mostly from municipal authorities, described the army opening fire only after it lost control of the mob, which had become intolerably violent. In attempting to explain the clash, early newspaper coverage framed the event in nationalist terms, but did so in conflicting ways. Few early reports noted the Jewishness of Löwenstein or Feuerstein, and some didn't even identify the opposition as Zionist, claiming the contest was between Löwenstein and Balicki.Footnote 58 Several reports claimed that the mob included workers from Boryslaw, while the district commissioner, Thaddäus Piatkiewicz, added that many of the provocateurs were Ukrainians who screamed ethnic slurs at the Polish soldiers, calling them “Mazuren.”Footnote 59 Another early report described the mob as mostly “Social Democrats and workers with very few Jews among them.”Footnote 60

Others blamed Zionists nearly exclusively. Several papers condemned a local Zionist leader (Aberbach) for inciting the mob, which allegedly stoned the military following his assurance that soldiers were forbidden to fire.Footnote 61 Another correspondent insisted that Zionists had also attacked the headquarters of the Social Democrats and that fights broke out between Zionists and workers. This grew worse, he wrote, when “Zionist workers” from Boryslaw arrived in the afternoon and added their numbers to the mob. Moreover, he claimed (falsely) that the army first attempted to disperse the crowd with bayonets, as required by the law, then fired a warning shot into the air, and only thereafter fired into the crowd, which was storming their position.Footnote 62 Some socialists also described the rioting mob as primarily Zionist, though they still blamed the massacre on a breakdown in military discipline.Footnote 63

Stanisław Łyszkowski, Piatkiewicz's deputy, took personal responsibility for giving the order to fire, stating that the military had wanted to disperse the mob with live fire already that morning but that Piatkiewicz tried to delay as long as possible.Footnote 64 Łyszkowski claimed that following its destruction of the offices of the Jewish community council, the Ringplatz pharmacy (the owner was an ally), a coffeehouse, and Feuerstein's home, the mob allegedly turned to the polling station, and Piatkiewicz felt he could no longer delay the order.Footnote 65 The French government publicly supported this version of events and exonerated Austrian forces for the death of a local French teacher, although later they quietly secured ten thousand crowns plus reburial expenses from the Ministry of Interior for his family, intimating guilt.Footnote 66 Following the massacre, both Łyszkowski and Piatkiewicz were temporarily suspended, but both were later restored to their positions.Footnote 67 Dozens of surviving victims, in contrast, were later sentenced to prison time.Footnote 68

Very different is the consensus that emerges from the Zionist press, the Ukrainian national press, the German and Polish liberal press, the socialist press, memoirs of Drohobycz residents, and the statements of numerous parliamentary representatives (Figure 17). First and foremost, others emphasized the context of extreme voter fraud having stoked the mob, which everyone admitted had grown violent.Footnote 69 Countless eyewitnesses testified to the fraud, including a friend of Löwenstein (Herman Bernfeld) who expressed disgust at the illegality of the proceedings.Footnote 70 Authorities later counted 603 votes for Zipper versus 5,979 for Löwenstein, an impossible tally necessitating more than 1,000 voters per hour (Balicki received 372 and Kobryn 768). Even setting aside the entirety of other evidence, these results were blatantly fraudulent.

Most importantly, most sources agree that by the time of the shooting, the violence (if not the emotions) had largely subsided. In other words, no mob threatened the polling station, as Łyszkowski claimed. Correspondents emphasized a common consensus that the army used excessive force against a peaceful crowd and denied military claims that any warning was given before the live fire.Footnote 71 Breiter and Straucher brought more than a dozen eyewitness reports confirming this calm, including men who personally spoke with Łyszkowski and other military commanders just before and after the shooting.Footnote 72

Worse, almost all the victims were shot in the back; soldiers fired even as the crowd fled the scene. This was confirmed by numerous eyewitnesses (Lustig found his brother shot in the back) and by the director of the hospital, who testified that most of the victims on whom he operated were shot in the back, while others died of bayonet wounds (Figure 18).Footnote 73 Breiter elaborated at length on the exceptional cruelty of Łyszkowski and the police, describing one scene in which Łyszkowski and an officer nearly beat a man to death before arresting him.Footnote 74 Most witnesses also claimed that the army prevented them from attending to the casualties for over two hours, costing several additional lives.Footnote 75

Figure 18. “The Bloody Elections in Drohobycz: Victims of Election Day in the Jewish Morgue.” Das Interessante Blatt, 29 June 1911, p. 3. Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library.

Though some testified that the soldiers who fired had been standing since 4:00 a.m. with nothing but coffee to eat or drink—and hence suffered from thinned patience and restraint—reports from victims, witnesses, and the city administration make it clear that the shooting was not a spontaneous defense against a storming crowd but rather was planned by the civilian leadership in advance.Footnote 76 Two men even testified that a police officer warned them to evacuate the area just before the massacre because shots would shortly be fired.Footnote 77 Moreover, multiple accounts claim that the shooting began even before the order was completed. An exhausted soldier allegedly misheard the beginning of the “ready, aim, fire” sequence for the final order, thereby increasing the casualties as the crowd had less warning to flee.Footnote 78 But it was no mistake. Breiter named seven men who testified that they heard Łyszkowski personally shout fire following the commander's initiation of the sequence, a criminal breach of protocol.Footnote 79 One witness testified that Łyszkowski told him he intended to fire in response to the sacking of Löwenstein's headquarters that morning, demonstrating that the decision to shoot was not a response to an immediate threat but rather a vindictive show of force against those who attacked his authority.Footnote 80

Blame is difficult to assign, but from the beginning Feuerstein, Łyszkowski, and Löwenstein (who was not even there) took the brunt of it. Saul Landau noted that election day strife and corruption occurred throughout Galicia, but nowhere else did the state fire on anyone, instead successfully defusing even violent clashes between political or ethnic rivalries.Footnote 81 No direct evidence ever linked Feuerstein to the order to shoot, but evidence did prove the electoral swindle that provoked the mob—and that Feuerstein clearly still ran the town. The Social Democratic representative Zygmunt Klemensiewicz focused his entire report around Feuerstein's power, only incidentally noting his support from Bobrzyński and Piatkiewicz. “Shoot the band down like dogs,” he was quoted shouting at Łyszkowski.Footnote 82 Unlike Zionists, who focused on the Jewish perpetrators, other witnesses focused on Łyszkowski, though most emphasized the context of voter fraud and Feuerstein's corruption.

Still, Breiter's speech “solely” blamed the provincial government and Bienerth for ignoring numerous appeals for help against the swindle in the run-up to the election. He also cited reports that the polling station was “flowing” with beer, wine, and schnapps, and noted that if the massacre was triggered by exhaustion, someone in military command needed to be held accountable for the decision to keep them on their feet from 3:00 a.m. [sic]. Alternatively, if taunts of “mazuren” provoked them, command must be held responsible for the breakdown in discipline. Of course, he insisted, there was no breakdown. They heard an order to fire.Footnote 83

Benno Straucher, the only Jewish Club member still in Parliament, focused like Breiter on political corruption by an interethnic clique rather than on the more typical Zionist polemic against assimilationist Jews. He too called for the minister of interior to remove Piatkiewicz and Łyszkowski so that a proper investigation could be conducted. Like the Zionists, in the end Straucher laid moral culpability with Feuerstein, Łyszkowski, and Löwenstein—“who is partly responsible because he knew that the electorate didn't want him”—but based on their corruption, not their Polish loyalty. Thus, for Straucher, too, the massacre was about oligarchy and corruption, not national rivalry.Footnote 84

Feuerstein did not remain silent in the face of mounting accusations of corruption and of his own culpability in the massacre. He vigorously defended both his public record and the election's integrity. “My public activity has always been directed to bringing Jewish and Christian people together in Drohobycz,” he wrote. That is why the “vast majority” of Jewish voters in Drohobycz supported him, as indicated in the election results, and so he had no need for chicanery of any kind. The mob, he argued, was fed by oil workers from Boryslaw and Tustanowice, sent by his rivals Spitzmann and Schutzmann, who were trying to influence the election in a district in which they did not even vote. “I have always been personally well disposed toward the Zionists,” he insisted, “and no one can prove a case that I rejected a Zionist who approached me privately for a favor.” He reminded readers that he had resigned the post of vice mayor in 1908 and that he advocated for Löwenstein merely as a private citizen. Most importantly, he strongly protested any insinuation of his involvement with the massacre. “It touched my soul deeply,” he wrote, adding that he was just as saddened and surprised as the Zionists by the massacre, which had occurred while he was inside the polling station fulfilling his duty as an election official. The blame, he concluded, rested squarely on those elements “igniting the passion of the mob.”Footnote 85

Feuerstein did not order the shooting, but his defense is not tenable. It denies the reality of broad support for Zionism generally and for Zipper specifically. It ignores widespread reports of corruption, including from among his supporters. And it obfuscates his enormous power in the city, evidenced in his active role on the ground directing the election and amply documented in both contemporary reports and later memoirs. Feuerstein did support the Jewish community, which he continued to head until 1914, but he was hardly “well disposed” toward the Zionists. Likewise, Feuerstein's claim that the mob was fed by outsiders fails to stand to scrutiny. On 27 June, Jacob Spitzmann vigorously denied the accusation that he sent people to stir up the mob in Drohobycz. They were busy with their own election, he wrote, and the absence of a single victim from his city belied the accusation.Footnote 86

Immediately after the massacre, Feuerstein fled to Vienna, barely escaping mobs in Zlochow and Vienna.Footnote 87 More than five hundred Zionist students protested on his arrival at the Vienna station and again the next day where he lodged.Footnote 88 The fact that an event in distant Galicia triggered protests and police intervention in Vienna again highlights the interconnectedness of politics in late imperial Austria.Footnote 89 When Feuerstein narrowly dodged another assassination attempt back in Drohobycz, the story ran in newspapers across the empire.Footnote 90 Hermann Tennenbaum, a Zionist student who attempted to shoot Feuerstein at a coffeehouse, was disarmed by a bystander. Tennenbaum initially confessed his intention to avenge the victims of Drohobycz but later withdrew his confession and was unanimously acquitted by the jury!Footnote 91

Löwenstein, an outsider who rarely visited Drohobycz, renounced his victory almost immediately after the election but did not repudiate its legitimacy. In fact, like Feuerstein, he explicitly affirmed it, writing that “the overwhelming majority united in voting for me” and insisting that he had no legal need to resign. “If I still persevered with my intention to reject the stated mandate,” Löwenstein explained, “it was only because it goes against my sensibilities to exercise a mandate which is linked at its birth to the memory of this terrible accident and unspeakable sorrow.”Footnote 92

Parliament devoted four days to the massacre. Dozens of delegates from several different factions demanded a government investigation with punishments for the guilty and support for the victims and their families. Social Democrats graphically described the scene of blood and death—“the streets were covered with the corpses of men, women, elderly, and children”—and the blemish it caused to Austria's worldwide reputation. In all, delegates debated eight competing “motions of urgency” in response to the massacre, all but one of which were rejected. Parliament passed only the motion of the conservative Polish nobleman Leon Biliński, with the support of the Polish Club (which he led) and the Deutsche Nationalverband, a progovernment German ethnic party. His was the tamest of the motions and protected most of the guilty while leaving any inquiry in the hands of the Galician courts, thus safely under conservative Polish control.Footnote 93 In other words, the tradition continued of Viennese support of the conservative Polish elite against Ukrainian, Jewish, or Social Democratic threat in exchange for its support of the crown. Breiter's motion, in contrast, explicitly blamed the catastrophe on the provincial government, while Ukrainian delegates described the massacre as another Polish blow against Ukrainian nationalist aspirations, barely mentioning the Jews.Footnote 94

Soon after he resigned his mandate and denied any intention to run again, Löwenstein announced his candidacy for the special election to fill the seat. His decision to run goaded those Zionists still interested in this Diaspora nationalist project to defeat him, but their calls for action went unheeded. Memoirs could not explain why Zionists failed to nominate any candidate, but at the time many Zionists, including Zipper, had grown bitterly disillusioned by the massacre, and opposition to engagement with Austrian politics grew. Zipper refocused his energies on Jewish life in Palestine, particularly the Hebrew gymnasium in Jerusalem.Footnote 95 Without Zionist opposition and with Feuerstein still in power, Löwenstein easily “won” reelection.Footnote 96 Security forces maintained firm control without recourse to violence on election day.Footnote 97 Zionists bitterly lamented how Löwenstein and Feuerstein walked the streets of Drohobycz unmolested, popular once again in high society, for ultimately the key components of their power—wealth, social position, and government support—remained in place.Footnote 98

Memory and Meaning

Löwenstein's victory led to a period of despondency among Zionists. “He will sit in the Austrian Parliament,” wrote the Jüdische Zeitung, “as a living reminder of the bloody and disgraceful 19 June, the day of his first election.” The paper wrote that the true meaning of this “catastrophe” was not the number of dead but that the instigators of the “pogrom” were Jews. “There are days in Jewish history on which thousands fell. But they fell at the incitement of foreigners, the enemies of Israel. On 19 June 1911 the murderers were Jews! Jews shamefully murdered Jews! Jews were the organizers of the pogrom in Drohobycz!” World pressure forced Löwenstein to resign his seat, it claimed, but then his cronies pushed through his new election for a man who, as in June, did not even “dare to appear in the city.”Footnote 99

Zionists, in print and rallies, focused their rage on Feuerstein and Löwenstein rather than on Łyszkowski or any other government figure. They tried to use the moment to enflame popular passion against the “assimilationist” establishment symbolized by those two men whose “depravity” on behalf of this immoral ideology knew no limits. “The Jewish heroes from Drohobycz fell like Maccabees,” declared the Viennese Jüdische Zeitung. “Students, workers, shopkeepers, women, and girls lay in their deathbeds. Jews—remember these victims always!” In this way, the paper linked the Zionists not only with the victims but also with the broad Jewish masses. The paper did name the Ukrainian dead among the victims, but it did not identify them as such, and it otherwise packaged the massacre as a Jewish affair. It also organized a campaign to support the survivors and printed the names of every donor to the fund, suggesting the movement's paternal leadership of the Jewish people.Footnote 100

Landau likewise admitted that “the bullets did not ask about party affiliation or nationality” but still described the massacre as primarily a Jewish event, calling upon Jewish leaders in the West to come to their aid.Footnote 101 Even the Drohobyczer Zeitung—a Jewish paper, though neutral in the election despite the publisher's Zionist sympathies—cried out in its initial coverage, “A terrible mourning for the Jews of Galicia.” It promised to keep an open mind about guilt and responsibility but ended its front-page obituary with the Hebrew verse, “The blood of your brother calls out to me from the ground”—God's rebuke to Cain after he murdered Abel.Footnote 102

Similarly, when Löwenstein spoke in Parliament for the Polish Club the following year, the Jüdische Zeitung characterized his acceptance by the Jewish leaders in the Polish Club as nothing less than treason. “Around him sat the House Jews of the Polish Club, [while] Herr Feuerstein (!) from Drohobycz and Schmelke Horowitz from Lemberg listened to his words from the gallery.” In this way the paper pulled Samuel Horowitz, Löwenstein's coleader of the “Jewish Electoral Organization” (the so-called hausjuden), into complicity. “The moral author of the Drohobycz mass murder as speaker, the actual executioner Feuerstein as listener and no catcalls interrupted Löwenstein. No hand raised itself to point to denounce Löwenstein, who delivered his speech to a quiet audience and final applause.” Not even the Social Democrats spoke out against him, it noted, thereby also evoking Zionist dogma about their unreliability as political partners. Ignacy Daszynski (leader of the Polish Social Democrats) is chairman of the legitimations committee, he complained, but only helps the hausjuden, while the Social Democrat Herman Diamand (born Jewish) is no better than a “Polenklubjude.”Footnote 103

Others targeted Löwenstein as an agent of Polish nationalists as well, packaging the story as another blow against Jewish national rights. The Jüdische Volksstimme, for example, described only Jewish blood spilled by this “wretched, Asiatic-barbaric shameful business” orchestrated by the Polish nobility and their Jewish lackeys, “traitors taking their Judas payment of a parliamentary mandate.”Footnote 104 HaMitspeh likewise focused on Löwenstein, portraying him as a traitorous agent of the Poles who “killed the Jews on his behalf.” “The voice of his brothers’ blood from the ground will ring in his ears all his life,” declared the religious Zionist paper, but the blood will act as glue for national unity. The Jews will never accept a foreign nationalism; they remain united against its traitors and demand their national rights.Footnote 105 Only in July did it finally mention Łyszkowski and Piatkiewicz, celebrating their suspensions, but it quickly refocused on Löwenstein. He may not have personally spilled blood, the paper admitted, but he had a “connection to the murder” by conducting a fraudulent election.Footnote 106

Though Ukrainian memory would soon relegate the Jewish role to the background, this sentiment was also echoed by the Ukrainian nationalist paper Dilo. It spun the standard Ukrainian line of Polish oppression by presenting the anti-Polish opposition as a Ukrainian-Zionist alliance against Catholic Poles and their Jewish allies. As in 1907, it celebrated Jews attempting to overthrow Polish hegemony by voting for Zionists, describing the massacre as “payment for the centuries of their service.” Dilo called the massacre a rite through which Jews were “baptized in blood” and hoped it would transform them into fighters for their own national movement, which would join the Ukrainians in overthrowing Polish rule. Like the Zionists, Dilo focused on Löwenstein and Łyszkowski as instruments of that rule—although unlike their former partners, Dilo at least acknowledged the interethnic alliance fighting against it.Footnote 107

The Zionist press did not simply cover the massacre more thoroughly; they literally reframed it to fit their ideological agenda, as in this front-page image in the style of Jewish death announcements (Figure 19). Always remember the names of those to blame, it demands, the traitorous Jews Feuerstein and Löwenstein. In Russia, Jews are murdered by “hired, drunk thugs,” but here in Drohobycz, “the people were delivered to the knife by their own Jewish tormentors.” The paper eventually admitted that Łyszkowski gave the actual order to fire but insisted it was only under the strict direction of Feuerstein.Footnote 108 Likewise, when the socialist Zionist Hapoel Hatzair asks rhetorically “And who are these killers, these murderers,” readers already know the answer: “Feuerstein and Löwenstein.”Footnote 109

Figure 19. Front page of Jüdische Zeitung, 23 June 1911. Source: Compact Memory.

Zionists explained Löwenstein's guilt by arguing that although he never “dared” to show himself in the district, he left it to his “cronies, the oil speculator Feuerstein and the brothel owner and pimp Steinhauser” to run the election.Footnote 110 One article reviewed the electoral corruption, all allegedly protected by Bobrzyński, and described exhausted protesters withdrawing when “suddenly the murderers Feuerstein, Steinhauser, and the district commissioner Łyszkowski let loose shots on the gathered spectators, including elderly, women, and children.” While the liquor flowed in torrents, Löwenstein was “elected.” Evoking the Zionist mantra of intractable antisemitism while ignoring widespread support in Parliament for stricter sanctions (not to mention the many Ukrainians who died alongside their Jewish neighbors), the author wrote that no party supported punishing the murderers. They went free, and Löwenstein entered Parliament. His accomplice Feuerstein, “the symbol of the deepest depravity and the most hideous product of Galician-Jewish assimilation rules again in Drohobycz.”Footnote 111

Not only Zionists reframed the massacre as an entirely Jewish affair. The Jewish socialist paper Di Varhayt, for example, headlined, “Jewish Blood Is Spilled in Galicia: Thirty Zionist Men and Women Are Shot.” The paper claimed that every victim was not only Jewish but also a Zionist who “spilled their blood for their Jewish party.”Footnote 112 Even the anti-Zionist Der Tog, which had supported Löwenstein and at first blamed the Zionists for provoking the massacre, now announced the deaths in that same boxed style, describing them as the result of a fratricidal conflict over a meaningless political battle. The victims were martyrs—“Jewish holy martyrs”—of a struggle provoked by Zionists against other Jews, an internecine narrative with Jewish victims and Jewish perpetrators, a conflict of “Jews against Jews.”Footnote 113

Over time, memory of the non-Jewish victims almost completely disappeared, as did mention of its non-Jewish perpetrators. On the massacre's first anniversary, the Jüdische Zeitung again draped its front page with a large black box and the boldface headline, “The Martyrs of Drohobycz.” The “dead” had become “martyrs.” At an overflowing memorial service in Vienna, speakers recalled the events of the previous year and decried the lack of any prosecution. Whenever they mentioned Löwenstein or Feuerstein, the room filled with calls of “pfui,” “murderer,” and “traitor.” The resolution recalled the “martyrs” as victims of a struggle for the freedom of the Jewish people, ignoring that most were random civilians and were not even all Jewish.Footnote 114

In contrast to this Viennese packaging, Drohobycz citizens recognized the interethnic nature of the story. Local Jews, Ukrainians, and Poles in Drohobycz organized their own memorial on its first anniversary in 1912. The services started in local churches and a synagogue and then proceeded to the Jewish and Christian cemeteries, where speakers spoke of oppressed people from all three communities fighting together for human rights and liberty.Footnote 115 The local “rescue committee” likewise consisted of Jews (Zionist and not), Ukrainians, and Poles.Footnote 116

Nevertheless, it was the Zionist construction that dominated recollections of Drohobycz Jews decades later. Holocaust survivors mainly recalled the massacre as an attack by Jewish oligarchs against innocent Jewish civilians. Hirshaut, for example, framed the entire story around Feuerstein, ending his narrative with Feuerstein's flight from Drohobycz without mentioning any non-Jewish perpetrators.Footnote 117 Nathan Gelber likewise blamed Feuerstein alone in recounting the event in his history of Drohobycz Jewry and noted only Jewish victims.Footnote 118 Mordechai Kaufman described the tragedy as occurring when a “Hungarian” regiment under the control of the city and local “moshkos” shot and murdered tens of Jews while their assimilationist candidate, Löwenstein, won. For Kaufman, the shooters may have been a foreign militia sent by the state, but they were under the control of the “moshkos,” and the victims were simply “Jews.” Moreover, in discussing Zipper's love for Palestine, Kaufmann explicitly linked the massacre to the subsequent spike of anti-Jewish violence in Europe. “From the blood bath in Drohobycz in 1911, through the Galician slaughter during the [First World] War, until the tragic November [1918] days of the great pogrom of Lemberg Jewry,” Kaufman wrote, Zipper's vision of a future in Palestine never wavered. He thus directly connected Drohobycz's Jewish perpetrators to the murderers of those later massacres, while exploiting it as proof of the wisdom of statist Zionism, the dominant strain by 1945.Footnote 119

The massacre even inspired the creation of a local folk song, a reworking of a ballad previously sung at Bundist rallies about martyrs murdered at a strike. The song must have been composed shortly after the massacre, and it was sung in Galician cities well beyond Drohobycz, eventually evolving into an Israeli version in Hebrew.Footnote 120 Among the villains, only Feuerstein and Löwenstein merit mention in the lyrics. The heroine may have been inspired by a real victim, Chana Bell, shot dead that day at nineteen.Footnote 121

Ukrainian memoirs of the event are scarce, but they recall it in nationalist terms, similar to their representatives in Parliament at the time. For example, Viktor Patslavs'kyi, who moved to Drohobycz just after the massacre, wrote decades later that the army fired at the “Ukrainian townsmen-electors who marched in ranks to the polling station,” correctly naming Dmytro Tatarsky as among the fallen. His is a purely Ukrainian story, perhaps because he only heard about it later, his memory shaped by a Ukrainian nationalist agenda.Footnote 123 The Hungarian historian Oscar Jaszi recalled it similarly, describing the “volley loosed upon the electorate which resulted in twenty-seven deaths and eighty-four serious injuries in order that the reign of the Polish Szlachta should be maintained over the Ruthenian peasants.”Footnote 124 As recently as 1999, a Ukrainian article on the massacre never mentioned Zionists (calling Zipper a Social Democrat) and described the mob as Ukrainian protestors led by Tatarsky, whose grave it pictured. The few names of victims included were Ukrainian. The author noted Feuerstein's corruption but blamed Piatkiewicz and Łyszkowski for the crime, concluding,

The events in Drohobycz were not random. They were part of the continuous violence committed in Galicia [of Poles against Ukrainians] with the help of police and troops. The bloody elections demonstrated that the ruling circles in Galicia were no longer able to preserve their power without resorting to violence in its most extreme manifestations, the armed one.Footnote 125

The massacre stuck in Polish memory as well. The Polish painter Feliks Lachowicz (1884–1941?) painted this watercolor almost thirty years later as he imagined the scene, Polish victims murdered by the Austrians with the synagogue clearly in the background, hinting toward the Jewish story but also reflecting the actual image if viewed from Stryjska Street (Figure 20). Its text, “The hideous system of Galician elections based on lawlessness and the suppression of the partitioning powers,” tells a story of Polish oppression. In 1939, a Polish historian included the story in his history of Drohobycz, graphically detailing Feuerstein's power, Łyszkowski's murderous role, the hysteria of the day's events, and concluding with the salvation to come with Poland's rebirth so that Drohobycz citizens were finally free, “governed not by foreign law but by our own law.”Footnote 126

Figure 20. Feliks Lachowicz, “Bloody Elections.” Source: Biuletyn Stowarzyszenia Przyjaciół Ziemi Drohobycziej, 22 March 2018.

Conclusion

The dichotomy between the “assimilationists” and Zionists was a misleading construct. These Polish–Jewish leaders were corrupt and antidemocratic, but they were also proudly Jewish and devoted to their community. Galicia has a long history of Zionist provocateurs vilifying assimilationist Jewish leaders in Polish-language Zionist papers, while many of those assimilationists encouraged young Jews to study Hebrew and express Jewish pride.Footnote 127 Unsurprisingly, the Zionist press failed to report the ten-thousand-crown donation by Löwenstein, three thousand by Feuerstein, five thousand from Artur Gartenberg, or other non-Zionist efforts to support the victims.Footnote 128 Nor did they report Feuerstein's establishment of a Jewish orphanage following his return to Drohobycz, a project started by his father, quickly raising the necessary funds from among oil rich Jewish families.Footnote 129

This massacre exposed a coalition of disenfranchised citizens struggling to overthrow an entrenched local oligarchy. Feuerstein, although inclined toward Polish culture, was not an extremist. He was defending an economic and political order and his own power, not Polish nationalism. Even his Polish opponent was nominated not on national grounds but as part of internecine oil politics. Moreover, most of his opponents understood this. The Hebrew paper Hatzfira explained Zipper's popularity by noting that “most Jews are poor—artisans, workers and lower class—who have no connection to assimilationism or assimilationists,” suggesting this primacy of socioeconomic factors in Jewish opposition to Feuerstein and his clique.Footnote 130

The massacre also had nothing to do with antisemitism. The Polish candidate was a proud Jew, as was the man engineering his election, and there is no evidence of antisemitic rhetoric or even behind-the-scenes antisemitic sentiment playing any role. No non-Jewish paper—not even the antisemitic völkish press—emphasized the Jewish aspect of the story beyond noting that Zipper and his supporters were Zionists.Footnote 131 The Austrianness of Galicia's Jews went unquestioned and unchallenged. The Zionist attempt to use this massacre as evidence of the futility of assimilation or the intractability of Polish antisemitism reverses its actual meaning.

Finally, what did the massacre signify about the meaning of the empire in the lives of these provincial Jews and their neighbors? It certainly highlights the dominant role of local power over any imperial ideal. Dynastic loyalism and Austrian patriotism, sentiments so often used in describing this period, did not emerge from these sources. Nor did national conflict play nearly as significant a role as nationalist leaders would claim. Drohobycz voters may not have been “indifferent” to nationalist sentiments, but other agendas guided their robust engagement with this modern political process.Footnote 132

Yet, different players managed to fit the massacre into broader imperial or national narratives. For Zionists, it was another example of the assimilationist enemy repressing the Jewish masses from realizing their proper leadership of the empire's Jews. For Ukrainians, it highlighted Polish repression of Ukrainian national aspirations, while interwar Poles remembered it as an example of Austrian oppression in their occupied homeland. Social Democrats likewise ignored the Jewish story and focused on the “scandal of the state” whose military could commit such a crime, and they targeted their rage on the imperial government, particularly Prime Minister Bienerth.Footnote 133 Benno Straucher, the populist Jewish nationalist, focused more accurately on its exposure of political corruption at both the municipal and imperial levels, although he also used the opportunity to glorify the record of the Jewish Club and vilify the Jewish members of the Polish Club. For Ernst Breiter, it symbolized his vision of a shared imperial identity that transcended ethnicity and nationality. Breiter celebrated the public revelation that Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians all suffered equally under the oppression of a corrupt oligarchy: all of them spilled blood on 19 June. “Believe me,” he declared in Parliament,

the innocent blood spilled in the streets of Drohobycz did not fall on fruitless ground. On 19 June, for the first time, a real equality came about. Jewish blood for the first time mixed with Polish and Ukrainian blood. The unworthy system treated Poles, Ukrainian and Jews completely equally, when it came to the elections, pushing through a candidate acceptable to the executioners of Galicia! And believe me the memory of that murder in Drohobycz will not disappear without allowing this teaching back into the human heart: only the combined strength of the Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish peoples can push aside the ruling system! Their blood will be avenged in the downfall of the system and its replacement with freedom and equality.Footnote 134

Breiter obfuscated the ethnic aspect of the massacre (Jews and other Poles vs. Zionists and Ukrainians) as much as Zionists Judaized it, refusing to remember Ukrainian, Jewish, and Polish blood mixing on that street, or for that matter even the existence of a Polish democratic candidate. Nevertheless, his story of oligarchs and those whom they oppress, transcending national differentiation, came far closer to the truth than the nationalists who repackaged it for their respective struggles.

Ultimately, while all the parties sought redress through imperial avenues, the story highlights the limits of imperial democratic reform in this distant province, where rights on paper did not necessarily translate into rights in practice. This massacre was mostly about raw urban politics, about an oil-rich oligarchy adapting to the democratic age and a political alliance between the imperial center and provincial elites that secured the election of the conservative candidate, even as socialist, Zionist, and other progressive forces managed to overcome these odds elsewhere. Oil wealth and the government protection it bought made a difference in Drohobycz, but local bosses successfully manipulated results elsewhere as well, and, as in Drohobycz, for reasons unrelated to national sentiment.Footnote 135 Even in this highly charged nationalist environment, nationalist motivations were far less relevant than the nationalist media—and later collective memory—would have readers believe. Instead, nationalists used this election and the massacre as ammunition for their constructed national struggle, and they did so very successfully.

In any case, memory of “that murder” does largely disappear, and neither Ukrainians nor Jews seized the moment to forge a vision of a shared destiny. Their imperial relationship, along with Feuerstein's ties with his Polish allies and his grip on the city, crumbled in the furnace of World War I. Today, a single Soviet-era plaque marks the site, placed in 1969 to commemorate the tragedy (Figure 21). Its simple message in Ukrainian—designed to blame Western imperialist powers for wrongdoing in the region—comes closer to the truth than most of the subsequent nationalist memoirs: “At this place in June 1911 Austrian authorities committed a bloody massacre on the voters.”Footnote 136

Figure 21. Soviet-era plaque placed in 1969 at the site of the Drohobycz tragedy. Photo: author.