Venturing into the Hinterland

Post qualitative inquiry does not exist prior to its arrival; it must be created, invented anew each time. (St. Pierre, Reference St. Pierre2019, p. 9)

They thought they felt something, perhaps. The wisp of an outline, yet not distinct enough to trace. Good. They circled it, at times, and at other times found themselves within. As they walked (a sort of walking. Figurative but real. Digital, but here. Over months of events), it curled open and headed in several other directions. Foldings in the backcloth that furrowed them along until, as they walked and talked, they felt that perhaps a territory was becoming simultaneously clearer and more obscure, that they might find a way to enquire, to start, even as it meant becoming the folds themselves. Then an email – a call for papers on post-qualitative inquiry… and an impulse to respond, but not sediment; decompose instead, branch like hyphae, make a filament (or even a few?). They aren’t yet sure where it will go, but it has a quality and rhythm. As they coalesce, Scott, Jamie, and Dave each come to this project differently (of course). From their own situations, with their own problems (even when shared, they are different) and here, in this paper, with different voices and different ways of writing – exposing a polyvocal attempt.

We (for the first shift in voice) take post-qualitative inquiry to be infused with a question mark, wary of attempts to make it a ‘thing’, and wary of important critiques – we want to keep the politics vital – but also wary of its claim to difference (is it different? Or is it more like permission in certain spaces? And if so, for who?). And yet, here we are, drawn to potentials, to the opening of conditions, to the possibility of something still to come. We hope to make a shift, to realise (as in make manifest) ontology and its everyday performance as synonymous with environmental education. Environmental education as a life. At times we draw, grate, rake our worlds through, over and into each other. At others we pause, hold a breath and conceive with what we find ourselves of. Events. As virus. As researcher-educators. As fires, let loose and consuming homes. As imaginations of possible research presents and futures. As allegories of the moment. In truth, as of yet, we are not sure what else this will do (or what it can do), but we are striving to create conditions of possibility that may allow us to do something.

Each time I read the abstract I prepared for this paper, I get a little more pissed off that I am (a) attempting the impossible and (b) just being a wanker. (Riddle, Reference Riddle, Riddle, Bright and Honan2018, p. 61)

Smoothing Some Striations to Open (Our) Inquiry

Flick through the posthuman glossary. Page 34. Entry, Animal: ‘Animals are living beings of various kinds’ (Timofeeva, Reference Timofeeva, Braidotti and Hlavajova2018, p. 34). That’s obvious… A tangent in thought – Page 260, footnote 17, in Sheldrake's (Reference Sheldrake2020) Entangled life:

The system of classification devised by Carl Linnaeus and published in his Systema Naturae in 1735, a modified version of which is used today, extended his hierarchy to human races. At the top of the human league tables were Europeans: ‘Very smart, inventive. Covered by tight clothing. Ruled by law.’ Americans followed: ‘Ruled by custom’. Then Asians – ‘Ruled by opinion’ – then Africans: ‘Sluggish, lazy … [c]rafty, slow, careless. Covered by grease. Ruled by caprice’ (Kendi, Reference Kendi2017). The way hierarchical classification systems order different species can be seen, by extension, as species racism. (p. 260)

Hierarchical ordering, systemisation, classification, categorical thinking, all striations that have a function, but a function that can subjugate and oppress with racist undertones. Clearly, for us at least, Euro-exceptionalism subtly works all the way down through human categorisation and infuses the Linnaean system of classification. Take the Eastern Curlew, for example (sometimes commonly referred to as the Moon Bird, because the distance it flies in its life of migratory travels averages the distance to the moon). What is the Eastern Curlew east to? Europe.

Let’s flick back to the Posthuman glossary on animals (and please excuse the extended line of quotations). ‘According to the famous Chinese encyclopedia, quoted by J.L Borges, quoted by Foucault [Reference Foucault1973, p. xv],’ Timofeeva (Reference Timofeeva, Braidotti and Hlavajova2018) shares that:

animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies. (p. 34)

Did that make you laugh? Did it do something? Shatter something? Open something up? And what of the politics at play? It was not uncommon for Borges to create sources, mix real names with imaginary ones and, in the creation of a magical realist genre, disturb the taken-for-granted in the reader’s reading. No source can be found for this ‘famous encyclopedia’ and, as Longxi (Reference Longxi1988) notes:

[it] may have been made up to represent a Western fantasy of the Other, and that the illogical way of sorting out animals in that passage can be as alien to the Chinese mind as it is to the Western mind. In fact, the monstrous unreason and its alarming subversion of Western thinking, the unfamiliar and alien space of China as the image of the Other threatening to break up ordered surfaces and logical categories, all turn out to be, in the most literal sense, a Western fiction. (p. 110)

That aside, the (made up?) quote is now out there, rewording the world, and it did something for us.

But we could provide another more sombre classification: Extinct or not (yet?) extinct. We can find all manner of ways of classifying things, naming things, caging things, subjugating things, sedimenting and putting them in a box. Categorisation involves individuation and power. In their box, things may lose their shine, their affective capacities and, although they are contained, controlled and held in their place (apparently), they lose animacy, their life. Break them out of their hierarchical classifications and they might be able to do a little more.

We come to this Special Issue on post-qualitative inquiry with a range of intentions, affectations, contemplations. Each of us have been drawn to post-qualitative inquiry in different ways for our research. One of the draws has been an opening up of the ways we think and do (research). Yet, as post-qualitative increasingly becomes a label, a piece of language that creates a reality (Koro-Ljungberg, Reference Koro-Ljungberg2015), we don’t want that reality to become an overbearing singular transcendent reality that boxes inquiry in – another classified sedimented methodology to follow. Sedimentation, the search for solid ground, is a habit: ‘We constantly lose our ideas. That is why we want to hang on to fixed opinions so much. We ask only that our ideas are linked together according to a minimum of constant rules’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze, Guattari, Tomlinson and Burchell1994, p. 201). As practices become normalised, they can lose their radical potential. So our intention in this Special Issue is to let go of some rules and try acts of writing that let go of fixed grounding. You see, we don’t want to territorialise post-qualitative inquiry, because that would work counter to the open-ended fabrication that is made possible through poststructuralist thought and post philosophies that have fed into the emergence of post-qualitative inquiry.

We still aren’t sure what this is yet, nor exactly what it will do, but for now, at least, we think it will be an attempt at environmental education research that stories our realities. In other words, we remain open to life as it’s lived, and write to, through and with the events that shape the world(s) in which we live. And we will endeavour to remain open to the potentials that come our way(s):

In a world tending toward the colonization of smooth space – spaces which obey no categorical rule and are bound by no overarching institutionalized limit – I think it critical to look for and maintain spaces that allow proximities to becomings… (Halsey, Reference Halsey, Hickey-Moody and Malins2007, p. 147)

Thus, we take the invitation to contribute to this special issue by writing with freedom – to use writing as a mode of inquiry – within the events of our lives, and tease out the environmental conditions always present but often hidden in the formation of things. We use this as a kind of heuristic. But we can’t say what we will imagine yet – what we will do – as it is as yet unimaginable. So, we will work away, striving to create conditions of possibility that may lead us to the unthought.

A Climate, A Summer

It isn’t every day you feel yourself come face to face with an existential threat (although I’ve experienced a couple, such as the 2015 earthquakes of Nepal, but that’s another story…). This threat came infused in the air, drifting to our doorsteps (and through the cracks of our doors). The 2019/2020 bushfires – named the Black Summer – bluntly invaded the lives of many Australians, me included. As I write this now, I see on the news fires in the US, Turkey (followed by horrific floods) and Greece. Bushfire/wildfires aren’t unique to the life of Australians, but considering the existential threat of fires, I consider the Black Summer in Australia. Thinking back now, over a year later, hazy memories float back to me, out of sequence, in no order, through my fingers, keyboard and onto this screen here…

It was hot and heavy. The kind of heat that gets you sweating the moment you step outside. There was no sun in the summer sky, just a thick haze. Light streaked through thick smog, dark and oppressive. Smoke filled nostrils, soaked into bodies. Little flecks of ash drifted across the sky – burnt biomass lifted in the heat, floated on the wind. Likely a tree not long before. Or it could be anything really – ‘muted embodiments of dead’ as Verlie (Reference Verlie2021, p. 25) puts it. When the wind blew the other direction, it took the ash to New Zealand. Some of it settled on glaciers, darkened them, caused them to absorb more heat and melt faster.

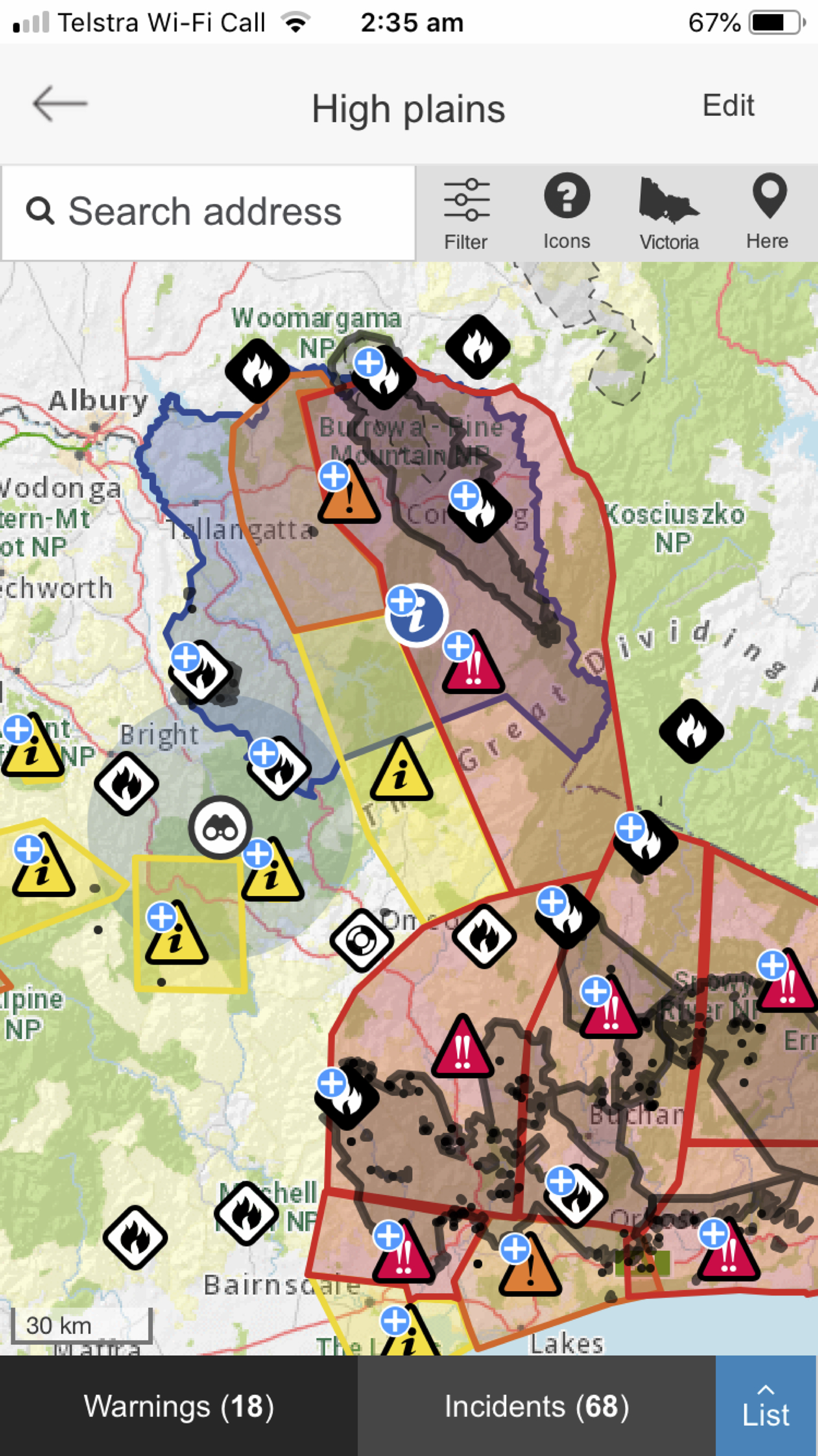

I considered putting on the air con. A pang of guilt. By extension, such conveniences influence climate, changes in climate and these fires (among countless other influencing factors). I flicked it on anyway. The emergency services app pinged most days (e.g., Figure 1). More being overrun. Places burning – places changing. Flames engulfed forests, houses, anything in its path. They wrapped alpine huts in tin foil to protect them. Bizarre but effective. Later, they dropped carrots and sweet potato from helicopters. They did it for the wallabies and wombats because there was no vegetation left, no food for them.

Figure 1. A screen shot from Victorian emergency services app on the 1st of January 2020.

Maybe Pyne (Reference Pyne2019) is right, we could be entering the Pyrocene. If we enumerate these events, the fires burnt around seventeen million hectares, blazing for months. At one stage, more than 420,000 fires were detected with fire fronts up to 6000 kilometres (Verlie, Reference Verlie2021). Over one billion mammals, birds and reptiles were said to have been killed. Some days people were advised not to go outside because of the smoke. Some started wearing masks. Mask wearing seemed strange back then. While they are burning a virus breaks out. Just after the ash settles the virus hits Australia, along with the rest of the world. Suddenly mask wearing becomes a new norm. For some, the fires were quickly forgotten, with the pandemic the latest unprecedented emergency. We will soon be taken up by viruses, but for now we will pause and take a divergent path in our writing.

Hopes

I’ve been reading an email Scott sent. The three of us are meeting online tomorrow to discuss the abstract we’re due to submit before the end of the month. I don’t want to talk about post qualitative research. I want to do something and to have something done. Something, what? Impressive? Sadly, perhaps. Ethical? I hope. Career enhancing? I’m not sure. Helpful? The multiplicity of drives is always present, as ever. And actually, do I really want to do this? Whatever this is. Maybe those drives are just some kind of foundation from which I can have a crack at justice? Haha. IDK. Let me tell myself that, so that I can keep it together a bit longer. For just enough. Scott’s writing is full of deadbodyash. And somehow the feeling of burnt fur, claws, sticks, are in my mouth and I feel a bit sick. It’s utterly awful. Reading that back it sounds trite. It’s not meant to be. Of course, those fires feel a million miles away from me. Barely registered in my life in Scotland. What is coming into being with this writing thinking project? We can’t force it. But I want to try the affective, pay attention to what is coming into happening as we all go along(ly). Worried about the ethics, as always.

But I don’t want to trace. I don’t want to tell you about post qualitative research. I don’t want to suggest some options. I want to go somewhere new. Human-centred ego trip or ethically inspired hope for a future yet to come? Quite likely both – though never only ‘human’ ;)

1 q§CFW– – GIL JUST WROTE THAT LAST BIT AND PUT CAPS LOCK ON.

Doubts

Opening up this document this morning, nervously, as I can’t really remember what I wrote and not sure it was anything worthwhile (or even coherent). I don’t know what I want this project to be and it’s hard working with others. Always so much doubt about placing fingers on the keyboard. What will they think about what I write? Using Google docs feels so immediate. I’m being pulled away from the keyboard. Being told to play the neoliberal game and listen to the VC address. But Mav is crying now too. Mav doesn’t care about post qualitative research nor what the vice chancellor has to say (I feel the same right now). Better go check on him…

Mav’s happy now. Just wanted a warm cuddle. I’m relieved by Dave’s writing that appeared overnight. There is something more real, raw and truthful about it. Can I write that openly? I’ve been thinking about voice again. We (me? – there I go, speaking from some unsituated universalist position – the God trick) always seem to be putting on a voice. What is an authentic voice? Dave’s seems authentic to me. What is an ethical voice? One from a situated position? I feel like my position is always moving anyway. Pushed, pulled, leaping, groping, over it, tired, nihilistic, optimistic, about the world, my sense of it – forces and trajectories. The lyrics of Eddy Current Suppression Ring’s Which way to go keep repeating in my head. I guess I’ll go listen to some music then. Forget deliberating and nod to a rhythm.

I pick up A Thousand Plateaus… because that’s what you do when you are confused and need some clarity, right? There’s a bookmark in there, in the refrain chapter. I read the page and it does nothing. I flip over the page and halfway down the next something pops out, something that resonates, that seems to fit the moment: ‘There is a territory when the rhythm has expressiveness. What defines the territory is the emergence of matters of expression (qualities)’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze, Guattari and Massumi1987, p. 366). It kind of works on me, it does something…

… funny looking back a few days later on this text. I think I was pretty tired! Mood changes my voice a lot. Especially when I let the words come out and don’t try to fabricate a voice. Can we untether voice a little? I’ve got to thinking of the fires again, but in an abstract untethered kind of way…

Fires, Identity and Subjectivity Beyond the Self: A Tangle of Life

The differentiation that takes place in each encounter, over and over again, is itself life. (Rautio, Reference Rautio2013, p. 398)

I was there but not there. My body – which is always a habitat, an ecology, for other bodies (is it really mine then) – was physically distant. It wasn’t in that place. That place of so much joy. But now it’s a place of suffering and I’m not there. Or so I thought. My memories are there, in that place. They curl on into the present, intruding into my thoughts, pressing on in this moment. Those memories meet this moment, meet these events and shape the present. It’s projecting forward, altering my future too. I’m part ‘in’ that place now. My physical body has been shaped by that place. All that mountain walking, ski shuffling, eustressing muscles, forming postures. The same postures that hold me up and project an empathy, a concern out east. The same postures that are starting to slump now after leaning over this computer too much. So that place – that bio-geographical location – has in part made me. I am of it. But I have part made it. Imagined it. It is material though. And this place matters (to me at least).

I’ve thought a lot about place. It’s one of those concepts isn’t it? An abstract idea, a piece of language, that ‘we’ (not all, but some) use to universalise a specific location. Universal but specific all at once. When I write ‘place’, what place do you think of? A sense of place – something someone perceives? To place something – to put it somewhere. Do we put our thoughts in place, co-shaping a place through imaginative, cognitive and material processes? Colonisers of Australia did that. The acclimatisation society brought little pieces (fauna and flora) of Europe across the world to make this strange place (to them) feel like home, to colonise it. To make the unfamiliar familiar. Human exceptionalism at play, imparting a certain collective’s desire upon others.

What about place as a bio-geographical location? Does that place it ‘out there’, separate from us/you/me when we aren’t physically there? Whose place is it, then? Does it distance and render it static? Possibly not. Hopefully not. Because the world is alive – even that inert stuff like rock. Lichens chew away at it. Weather wears it. Rock metamorphises. For example, Uluru has a draw, a certain gravity, and has done for time immemorial. In an animistic or process-relational ontology it all keeps on moving – going along(ly). It may be better to say places, then, to pluralise the concept a little, to keep it going along.

I’ve started to think of places as made of lines (for another example, see Jukes, Stewart & Morse, Reference Jukes, Stewart and Morse2021). It wasn’t my idea. Dave and Jamie prompted it awhile back (Clarke & Mcphie, Reference Clarke and Mcphie2016). Ingold and Deleuze and Guattari prompted them (I wonder what prompted them… I think Ingold’s father as a mycologist thinking about mycelial networks along with D&G prompted him. I think it was the rhizomes and nomads that possibly did it for D&G? … doesn’t even matter right now, but there is a line there). I have come to think that places are not necessarily geographically bounded. Places have a range of heterogeneous connections, at times geographically distant, that shape, move and implicate places. Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2011, Reference Ingold2016) meshwork is an idea that helps describe this vision of places. As places are not static, they are really an intermingling of pasts-presents-futures, of lines of life, all overlapping, knotting, implicating. There isn’t one unifying force, but there is ontological commonality. A body multiple, to borrow Mol’s (Reference Mol2002) term – or a singular multiplicity (Law, Reference Law2004). Ingold’s meshwork is made up of lines: ‘To describe the meshwork is to start from the premise that every living being is a line or, better, a bundle of lines’ (Ingold, Reference Ingold2015, p. 3). This is where ‘everything tangles with everything else’ (p. 3). Natures, cultures, humans, more-than-human, all bundle together, criss-cross, infuse and create – create the world we partially know as places.

Paths are a line of sorts. Drawing upon Ingold (Reference Ingold2011) and Clarke and Mcphies’ (Reference Clarke and Mcphie2016) provocations, places might also be knots, and it is along the paths of our lives that we encounter these knots. Here, in the movement of living, we entwine ourselves with knotted places in various ways that mutually reshape them and us:

Every entwining is a knot, and the more that lifelines are entwined, the greater the density of the knot. Places then, are like knots, and the threads from which they are tied are lines… (Ingold, Reference Ingold2011, pp. 148-149)

And…

To be a place, every somewhere must lie on one or several paths of movement to and from places elsewhere. Life is lived … along paths, not just in places, and paths are lines of a sort [I just realised I unintentionally plagiarized Ingold’s words above, oops]. It is along paths, too, that people grow into a knowledge of the world around them, and describe this world in the stories they tell. (Ingold, Reference Ingold2016, p. 3)

These textured images of the concept of place have helped me envision the multiple actants present and moving with/through places (in their own ways) and was part of the inspiration for the idea of more-than-human stories (Jukes & Reeves, Reference Jukes and Reeves2020). Dave and Jamie have referred to more-than-human stories as it narratives, commenting that:

More broadly, these it-narratives could be communities of microbiota continually pulsating in multiple directions rather than simply responding to things outside of their perceived boxes of taxonomic status, just as humans are not place-responsive in any cause-and-effect linearity. Life is not dot-to-dot. And so, places are not educational of themselves in a unidirectional manner. They cannot teach us as if we were a tabula rasa waiting to receive wisdom from some highly gendered romantically conceived Nature, ‘out there’. We are the ‘there’ itself. We are place/s. We are made of place/s. So what does it really mean to know place/s? There will always be secrets to/in places that hide in differing timelines, outside of our evolutionary heritage, our sensory bandwidth. There are countless narratives happening all the time, that perform at different scales, and temporal, spatial and sensorial frequencies, that we simply cannot perceive or even conceive (even with extra-sensory cyborgian additions like radar or ultraviolet detectors). (Clarke & Mcphie, Reference Clarke and McPhie2020, p. 1257)

Here they evoked an image of places that I resonate with. As they say (clearly influenced by Deleuze and Guattari [Reference Deleuze, Guattari and Massumi1987] and Ingold [Reference Ingold2011, Reference Ingold2015, Reference Ingold2016]), life is not dot to dot. Haraway (Reference Haraway2016) made a similar figuration: ‘Tentacularity is about life lived along lines – and such a wealth of lines – not at points, not in spheres’ (p. 32). In other words, life is felt along lines. But importantly, not just my life or your life – no human exceptionalism – more-than-human lives feel their way along lines and through meshworks, into bodies, out of bodies. Where lines of life knot are places – ‘everybody lives somewhere’ (Haraway, Reference Haraway2016, p. 31) – and where lines cross are meshworks. A vibrant relational field.

Ingold (Reference Ingold2016) makes a distinction between two classes of line: the thread (filament) and the trace. I think I’ve stopped making a thread and have started tracing… this all gets a bit messy and abstract doesn’t it. I have to keep asking myself, what does this haecceity do?

Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze, Guattari and Massumi1987) evoke a philosophy of the line, moving away from static points. Their discussions on an ontology of becoming involves the idea of movement. A staticised line is a point, a dot. Movement is a line, a becoming – without a start or destination: ‘A line of becoming only has a middle’ (p. 342). Becoming is the coexistence of movements – lines of life intermingling and meshing or knotting together. What does it do to think of educational contexts this way? I don’t have one answer. Do we think the purpose of education is to learn? Macfarlane (Reference Macfarlane2013) illuminates the etymological trail of the verb ‘to learn’, or to acquire knowledge:

Moving backwards in language time, we reach the Old English leornian, ‘to get knowledge, to be cultivated’. From leornian the path leads further back, into the fricative thickets of Proto-Germanic, and to the word liznojan, which has a base sense of ‘to follow or to find a track’ (from the Proto-Indo-European prefix leis-, meaning ‘track’). ‘To learn’ therefore means at root – at route – ‘to follow a track’. (p. 31)

There doesn’t seem to be a terminus to education then. And we have come back to lines. I suppose education is always environmental, happening along transcorporeal more-than-human lines – but definitely not an environment that ‘has been drained of its blood, its lively creatures, its interactions and relations’ (Alaimo, Reference Alaimo2010, pp. 1–2). An environment where learners emerge through relational fields (Hultman & Lenz Taguchi, Reference Hultman and Lenz Taguchi2010) is more nuanced and accurate, I think.

Lines keep returning in my thinking. Circling around prompting me. Sometimes I follow and trace, sometimes I try to create a filament, branch off like a fungal hyphae, embarking into other territory. Let’s wander a little further:

To embark on any venture – whether it be to set out for a walk, to hunt an animal or to sail the seas – is to cast off into the stream of a world in becoming, with no knowing what will transpire. It is a risky business. In every case the practitioner has to attend, not just in the sense of paying proper notice to the situation in which he presently finds himself [sic], but also in the sense of waiting upon the appearance of propitious circumstance. (Ingold, Reference Ingold2015, p. 138)

Are you lost in the labyrinth yet? I think I lost myself. Or at least I was hoping to.

I think what interests me about this elusive line idea is that it brings me back to a former self (while stretching me in new directions away from my ‘self’). My early twenties consisted of a single-minded obsession with skiing and kayaking – spending time in mountains and along rivers. That self is still here, just different. The obsession isn’t so single minded (at least I hope) – it was mostly a hedonistic pursuit. Travelling rivers, constantly scoping the horizon for a line. Scouting a rapid visualising a line – a path of travel. Or in the mountains, observing a face for lines of descent, lines of flight, safe routes of travel, more adventurous routes, or a path less travelled. The scouting view, scoping a line, is always so different from within the line. Living the line, being of the flow and moving with multiple forces was the goal. I’ve since fallen for places, thought beyond myself and my self-centred pursuits. I grew up in a culture full of bounded individualism mixed with plenty of human exceptionalism and privilege. But posthuman ideas (or the composting humusities of Haraway [Reference Haraway2016]) fermented and dissolved, blurred the boundaries of my skin and my ‘self’. My ‘I’ has become distributed as I am of a more-than-human world – theory has opened me to a transcorporeal self, which I have tried to decentre through considering a relational ethic. And this all brings me back to where I started this conversation, me thinking about the fires burning through the Alps, up hillsides, along river valleys, and my history, my life, being shaped by those places, emerging from the intensities of such a haecceity. Maybe this has been an ontological symbiography prompted by feelings of solastalgia.

But I still have an obsession with lines, and maybe I should write about what this idea might do.

Thinking with lines can decentre things and keep thought moving. Thinking lines creates conditions for movement which can stretch beyond the self, beyond the human and into relationality with bodies and affects. Moreover, thinking environments and places as continually made of lines enlivens any stasis and can even erase ideas of the ‘balance of nature’. Material environments might be thought through a realm of lines, as innumerable interconnecting agencies, as relational fields. As the environment – the world – is always changing – becoming. And in our current moment, ‘we’ might do well to forget about saving nature and may do better to cultivate ‘arts of living on a damaged planet’ (Tsing, Bubandt, Gan, & Swanson, Reference Tsing, Bubandt, Gan and Swanson2017) – a planet that has always changed but is currently changing – hastening – at rates and in ways that are increasingly problematic (to put it lightly). For me, what keeps me going is to not shy away, ignore or positively romanticise, but instead bear witness to the darkness. But also, to be ready for the growth and creativity that always comes from disturbance. There is no nature to save, but a more equitable future we can make. So in the midst, and on the wake, of continual disturbance we can compose a new liveable future… and maybe this is something that environmental education and environmental education research can do?

Okay Scott, let’s have a go with something else contemporary shall we? You mention ‘stretching me in new directions away from my ‘self’’. But, as well as ‘where’ is yourself, I might ask, ‘what’ is yourself?

Vīrus – Stream of Conscious

logue : Once, they said I should write ‘it is’ instead of ‘I think it is’. Curious. All academic writing is opinionated. How can it not be? I like the tidal pulls – both ways – and Brechtian performance of peer reviewing. I find it stimulating, if sometimes aggravating. The peer reviewers join ‘the thinking’ to become part of the assemblage that was once me, or Dave and I, or (now) Scott, Dave and I (we’re becoming quite a crowd eh?). Some of these opinionated views within the wider assemblage certainly may be more ‘empirical’ than others, but they are still influenced by their cultures thoughts and as such are compressed, within the confines of Enlightenment run-off … perhaps (they don’t like the ‘perhaps’ either). As I get older, I definitely become more unsure! ;-) I’ve also started to become more curious about other ways of writing/thinking/expressing that aren’t so serious. For example, I enjoy and respect the ontologically rooted humour of many First Nations peoples. This humour has a tendency to be condemned to the confines of nonacademic writing by some serious-minded scholars (Leddy, Reference Leddy2018; Lopez, Reference Lopez2015). Weird eh? A(n implicit) political move? It has racist over/undertones – don’t you think? Fortunately, First Nations humour can also be a coping mechanism against racism (Dokis, Reference Dokis2007).

I digress. I wanted to tell you that this writing is not at all like that! It’s most certainly ‘academic’. But … breaking free of the illusory, imagined, invented rhetoric that was designed to favour some people/epistemologies more than others. I do this in order to disrupt the status-quo of privilege (although I am very aware of the privilege inherent in this statement). Having said that, I will now go on to completely ostracise many people by writing inaccessibly about things that are assumed and not questioned enough…in my opinion! Oh, and I make up words too. ;-)

The Coronacene

An ancient Mediterranean landscape; an endangered species in the Amazon; the Library of Congress; the Gulf Stream; carcinogenic cells, DNA, dioxin; a volcano, a school, a city, a factory farm; the outbreak of a virus, a toxic plume; bio-luminescent water; your eyes, our hands, this book: what do all these things have in common? The answer to this question is simple. Whether visible or invisible, socialized or wild, they are all material forms emerging in combination with forces, agencies, and other matter. Entangled in endless ways, their ‘more-than-human’ materiality is a constant process of shared becoming that tells us something about the ‘world we inhabit’. (Iovino & Oppermann, Reference Iovino, Oppermann, Iovino and Oppermann2014, p. 1)

Many/most people in my field of work romanticise the idea of ‘reconnection to nature’ as something beneficial, pure, Appollonian and pristine. I can’t help but stir the assumptions inherent in this uncritical generalisation. One of my immediate responses is ‘really? You’d like to reconnect to dog poo? Tsunami’s? Earthquakes? Rubbish dumps? Plastic waste (yes, that’s nature!)? – I could go on. Recently, I’ve included a new addition to my running list of provocative examples – the Coronavirus. I doubt many people would deny its authenticity as a part of what they think of as ‘nature.’ Yet, I doubt many people would wish to (re)connect to it. But, we have entered the ‘Coronacene - a geological period in the Earth’s history that is becoming shaped by Corona-creatures - which include us’ […]

If human agency is distributed among phenomena, the coronavirus is a very dominant agential influence at the moment. We can’t ‘defeat’ it, we ‘become’ it – or it becomes us, in a very literal and physical sense. The coronavirus is currently (re)shaping both the narrative of our lives and our means of assessing those narratives and the larger one that we inhabit. (Mcphie & Hall, Reference Mcphie, Hall, Blackmore, Chaney, Hall, Kelly and Mcphie2020, p. 48)

This got me thinking. Like the zombie-ant fungus, Ophiocordyceps Unilateralis, ‘the merging of the coronavirus with humans produces something altogether different that will have ecological ramifications – trophic cascades – that affect the very structure of human societies around the world’ (Mcphie & Hall, Reference Mcphie, Hall, Blackmore, Chaney, Hall, Kelly and Mcphie2020, p. 48). Apparently, the Ophiocordyceps fungus can direct the ant to a certain height and force it to face a particular direction to help it spore. A single-celled parasite called Toxoplasma gondii can encourage rodents to lose their fear of cats, making it more likely that they get eaten and pass on the parasite. Spinochordodes tellinii instructs grasshoppers to drown so that the waterborne parasite can reproduce. Candida albicans may be one of the causes of schizophrenia and bipolar, instructing the host in a particular fashion that modern medical science labels as mentally ill and others label as mad or insane simply because we have compared the new version of the self to a normative model, an older, more populous and perhaps more conservative one. Candida albicans may not have a purpose as such but it certainly changes the behaviour of the host. However, re-reading these italicised examples, they appear very factual, very colonial (using the royal scientised Eurocentric naming of things) and unidirectional. Linear cause→and→effect. Very Linnaeus. Labelling, classifying, essentialising, hierarchising. As if the so-called ‘parasite’ is in control of the intention to act – the agency. It can’t work this way though. It must be a multi-directional co-emergence of events, spread in/of the environment. A distributed environmental agency. In which case, the species aren’t separate, one thing consciously acting upon another to make it other than the norm. The norm ‘is’ this Dionysion complexity always already. The ant was always zombie. And zombie isn’t dead. It’s undead. There is an inorganic life to everything. The evolutionary processes that mingle and merge species create fungus-ant hybrids that are another species, another thing, perhaps more fungus than ant now but also neither solely one or the other (a bit like Scott, Dave and I right now).

A his-story of the human is well-documented (and historicised). But what of the fungus or the virus? Don’t they have a say? And if they could say, what would they say?

An It-Narrative (of sorts)

‘Poison’ in Latin, we viruses are misunderstood creatures that are feared and shunned. There have been efforts to domesticate us for medical purposes – virotherapies – but attempts to eradicate us dominate conceptions, much like weeds, germs or rats. Yet, we are virus.

We make up assemblages of other creatures. We are a morphological species that transform our so-called host to become something altogether different – a different species. Not only do we form part of humans, we are humans.

All creatures make up assemblages of other creatures, depending on where you decide to draw your lines. After all, taxonomical boundaries are invented just as much as dermatological boundaries. Things are not simply skin-bound. All things leak and stretch, even thought.

Viruses can alter a creature’s gait, stature and style. We can be more prevalent in those most oppressed in societies, especially if those societies are socially inequitable. We are a political species. We can aid a government or destroy one. Yet, we all become virus eventually.

We inhabit a world between definitions of life and nonlife. Some suggest we are life-less and some suggest we are alive. Yet, all things can be articulated in life. [This human, writing with me now, came to that thought after reversing Dema’s (Reference Dema2007, para 1) comment that ‘life can be articulated in all things’]. If life is defined as an evolving, self-replicating entity, it would mean that viruses are very much alive, but isn’t this also true for rocks? Volcanoes can self-replicate and evolve, can’t they? The Earth, in this case, is very much alive and swarming with virus.

Take the human biome or virome. Humans are an assemblage of bacteria, fungi, mites, viruses, etc. Yet, that is only a very narrow understanding of what ‘humans’ are. As well as biological, humans are lithological, hydrological, tropological, topological, and conceptual. They are an assemblage of minerals, plastics, metals, electro-chemicals and neurons – around their stomachs and hearts, not just their brains – they think corporeally [or as Aliamo (2010) puts it, transcorporeally. Or as Clark and Chalmers (Reference Clark and Chalmers1998) put it, transcranially. Or as this human (Mcphie, Reference Mcphie2019) writing with me now puts it, environ(mentally)]. They are water and H2O – these two can exist independently of one another due to their ecological performance as physical concepts (as life-giver or as chemical solution), as well as becoming assemblages of other hydrological creatures, such a ponds, rivers and oceans. And if a river can have legal status, why not a virus? After all, there are trillions of viruses that inhabit/are humans…and rivers.

We viruses make up a genome of the planet, we fill your oceans, wind, soil – we are our oceans, wind, soil.

We viruses are the most successful species on Earth (I’m bragging now ...can you tell?) and we are of every species on Earth, transferring genetic material between species: ‘They are the drivers of evolution and adaptation to environmental changes’(Moelling, Reference Moelling2020, p. 669).

I think we viruses are entirely misunderstood by humans – or should I say ‘by viruses’, as that is what we are.

This is a photo of me below, second from the right – I’m smiling (Figure 2):

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2. Image from Goldsmith and Tamin, CDC (Reference Goldsmith and Tamin2020).

logue : I guess the trillions of viruses that make us what we are behave like a bulge of kids in a playground, playing, pushing, shoving, some bullying others, some joining Hitler’s youth. This is what viruses do. Some turn bad. But of course, this bad is always already someone/something else’s good, or nothing at all.

Intermede

Jamie, it seems even your emails could be infused with viruses, according to the automated responses that come through when you accept meetings: ‘Viruses: Although we have taken steps to ensure that this email and attachments are free from any virus, we advise that in keeping with good computing practice the recipient should ensure they are actually virus free’.

[Sorry Scott, I have to plug in again just here to this assemblage – after this paper has already been accepted for publication now – to respond to this idea of being ‘virus free’, because 2 weeks ago I became one of the Corona-creatures myself – part of the zombie horde – unclean. I think it was the Delta variant (that was initially nationalised/racialized as the India virus – out of the China virus – I didn’t realise viruses could have nationalities!). Not sure. Anyway, the virus that has now become part of me wants me to tell you how it has altered me. It only felt like the back end of a cold. But it made me feel dirty somehow. Degenerate. (Like the artists who were despised so much by Hitler and the far-right). I was infected. My taste has altered, perhaps forever (how would I know?). I haven’t kissed Jane properly since I had it. Not sure why. Maybe, I still think I can pass it on to her, even though a fortnight has passed. My proprioception has altered. I am a part of a new species. And now the online virus of this addition is infecting you too, Scott and Dave – oh yes, and you too…yes, you. Part of me, these physical thoughts that I’m having right now, also altered by the virus, are now part of you. This is ecological. It’s a trophic cascade in action, right now. This is environmental writing verbatim. Okay, now I can plug out again. Back to the pre-reviewed story. Sorry for the intrusion.]

Something to add in the mix Jamie? – old/new virus being released from melting permafrost – a link between climate change and the agency of viruses – maybe a previously frozen virus can write an it narrative as a response? … http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20170504-there-are-diseases-hidden-in-ice-and-they-are-waking-up

-

–Yes, that’d be good. Do you want to be the virus that responds?

-

–I can have a go, but equally happy to leave it to you if you like. I need to go back and work on some of what I started above, and might do that first. So by all means, go for it if you like.

-

–It seems this was a stream that became a bit of an oxbow lake, eh Scott?

Jamie, above you mentioned how plastic waste is also ‘nature’. I think many in our field get caught in the dualistic categorisation as they haven’t engaged in documentaries such as this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLgh9h2ePYw

The Youtube documentary ‘The majestic plastic bag’ describes the nature of the wild plastic bag, and the perils it faces in its migratory journeys. The bag in this video is very much alive. The agency of the plastic bag is often subjugated, as it is thought of as an inert individual object, only with one purpose of carting some groceries home. Such domestication (and anthropocentric utilitarian purposing) removes the bag from the assemblages that it emerges from and through. It makes me think of Ingold and his kite-flying… no thing acts alone… (more to tease out and play with here?) … a bit of ‘thing power’ from Bennett, Reference Bennett2010) might also be relevant.

-

–Like this!!! [written in later - It’s Attenborough as a flat ecologist!] It also reminds me of the video of the plastic bag in the film American Beauty, and it’s liveliness (it’s also been mocked in an episode of Family Guy).

-

–‘Do you have any idea how complicated your circulatory system is?!’

-

–Kites - also Maori kites as animistic extended limbs?

Another thing about nature (and maybe you wrote about this elsewhere?), but Alaimo (Reference Alaimo2016) highlights how the term is weaponised by homophobic perspectives. Specifically, to be straight is ‘natural’, whereas to be queer is ‘unnatural’. There is a supposed purity in straightness, akin the purity of nature, and something wrong if one isn’t that way inclined. But Alaimo notes numerous examples of queerness in animals, as examples of homosexuality in ‘nature’. This could be an interesting point that may resonate with your views on unequal and unjust uses of the concept, Jamie. This is just some quick notes, another thread to follow maybe…

-

–Jamie will have more on this for sure – we’re using a bit of Queer Ecology in a chapter for a Rewilding Handbook – what’s happened with that Jamie? Is it still with reviewers?

Yep. Here are a couple of quotes from it Dave:

Concepts like nature and wilderness are subject to the same forces of cultural invention as everything else. Therefore, they are gendered and sexed, usually in a heteronormative binary fashion (Mcphie & Clarke, Reference Mcphie, Clarke, Convery, Carver, Byers and Hawkinsunpublished...as yet). ‘“Nature” and the “natural” have long been waged against homosexuals, as well as women, people of color, and indigenous peoples’ (Alaimo, Reference Alaimo2010, p. 51).

The ‘ontology-axiology of reproductive heteronormativity’ contributes to the global environmental crisis ‘because the world is imagined to have this great capacity to reproduce itself infinitely’ (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Azzarello, Brown, Hogan, Ingram, Morris and Stephens2012, p. 85).

I know these are only short extracts that might feel out of context, but it also might nudge the reader (the new author) to seek out our chapter – Queering Rewilding: Ecofascism, Inclusive Conservation, and Queer Ecology (Mcphie & Clarke, Reference Mcphie, Clarke, Convery, Carver, Byers and Hawkinsunpublished...so far) – for further context.

[This was how things happened during the process of inquiry. Some sentences set up conditions for new sentences, others trailed off. There could be more to explore in the unfinished threads above, but that is for another day] – another oxbow lake Scott?

Writing with Scott’s lines and Jamie’s viruses: Practising political ecologies

Last week I heard a student say it as well. We are the virus. The context was all wrong though. They weren’t being literal. They were meaning it in the same way as Agent Smith in The Matrix. Not in a good way, but a bad way…

Now it’s this week, and Jamie is late for the meeting so I give him a call. No answer. Scott and I look at each other on the screen. Small talk evaporating. I call Jamie again. Nope. Nothing. What do we do? We…we meet what’s going on with a dance of intimacy. We talk work, life and project through each other. Scott is in lockdown still. I loved Scott’s new writing. I’m wearing a ridiculous woolly orange jumper. Scott is too polite to say anything about it. [Sorry to interrupt Dave. I thought your jumper was fantastic. I was about to say something but got distracted by the leaky roof!] We’re strangers grappling to get somewhere and, save writing some of the abstract and turning up, I haven’t contributed much to our Google doc. So, I’m wondering what to do, but I’m not sure if I say this or not. Scott is an ethical guy, and he asks me what I’m interested in at the moment. The question might have nothing to do with the project. But it’s a helpful question. I do the thing where I don’t look at the screen while I talk, and I start saying something hazy about political ecology. Neither of us know what I’m getting at. At least, Scott might know what I’m getting at, but I’m not sure. I decide I want to follow this.

Last week, she said we are the virus.

The day before she said this, the group of students and I had been looking for liminality on the Cairngorm plateau.Footnote 1 We’d wandered out of Rothiemurcus Lodge, above the recently harvested tree crop. The endless silvery broken stumps and smashed wood leaving a landscape reminiscent of Mordor, echoed by the grey Scottish sky. We’d veered away from that site of extraction, ducking off the gravel track and through young trees – out into rough ground and through the last of the blaeberries. We walked a line beneath the plateau, through sparse copse of Scots Pine, towards the wide-open mouth of the Lairig Ghru. The trees hunkered on low island mounds above the bog, clutched together for fear of being swallowed, ignoring social distancing on the high blanket heather. We’d stopped at the edge of the tree line, remarking on the difference we felt emerging from the homely sheltered stand and onto the wide laid windy spread of bog; rising open land, coalescing moraine and crags, and far off high rounded tops. We discussed liminality on this forest-edge, and the students were asked to find something liminal around them. To find a space where something became something else. There was much to look at. Above, speeding clouds became wind as vapour condensed in and out of perception. Below, a crafted mound of Scots pine needles and earth heaved several feet above the heather as wood ants went about wood-anting. Cotton-grass raged on brakes in the mire. Rain had us gripped with its threatening absence.

That’s an odd way of writing, Dave. Isn’t it a bit…romantic. Scott and Jamie both veer away from this. And you know it’s a problem. What are you getting at?

Hold on. I’m setting a scene. And besides, it’s nice.

We are the virus.

After 10 minutes of sitting and thinking, watching the students roam the bog-edge, I went over. We gathered, and started our liminality-trail at a tree.

At first the young Scots pine held our focus as we discussed its obvious difference to the world around it. It stood there, an individual making its way upwards in the world. Someone notices that the tree is solid compared to its surroundings – but of course this is only a matter of perspective. The tree is, by its own terms, going as fast as it can in a completely normal register which remains alien to us. Further, as we looked at it, and placed our hands on it, the tree became the-world-around-it. As Ingold (Reference Ingold2008) notes, it’s difficult to actually say where a tree begins and ends. Do the creatures living under its bark see a tree? Or something else? It seemed the tree could be many things and nothing depending on the practices of wording and attention at play (Mcphie & Clarke, Reference Mcphie and Clarke2015). What might this do, pedagogically? Multiple perspectives might imply humility – great – but they also might not. What they cannot escape, however, is politics. Actually, this isn’t really about different perspectives. It’s about different worlds. This is cosmopolitics, in which ‘there is not a single world revealed through a multiplicity of perspectives; instead, there are a multiplicity of worlds each entwined with one another, and made present by different sets of practices’ (Robbert & Mickey, Reference Robbert and Mickey2013, p. 2). This isn’t relativism either – these worlds are all present together. Practices matter in both senses of the word matter – they have consequence. Living in one world, where the tree is an object in a landscape, has different manifestations to practising the tree as a ‘gathering together of the threads of life’ (Ingold, Reference Ingold2008, p. 4).

There’s something else here. With this cosmopolitics stuff. I can’t quite pin it down. We are the virus. Keep going.

We moved along our liminality trail. To a dead stick. But, all things can be articulated in life (Jamie). So not only dead, then. To a small patch of ground. Tiny in comparison to this open plain. But, the patch is a lithological, hydrological, tropological, topological, and conceptual universe (Jamie). Indeed, several universes. So not only tiny, then. And then our trail took us to a line of water, concrete in its liminality in the landscape. A solid line. And yet, where does the water end? Are there really banks to this narrow ditch? Or rather, networks of roots, filaments, growths, seething beings all muddling multiple worlds together? So, not only a line then. Or all lines. All movement (Scott).

One thing’s liminality is another thing’s whole. Wording, attending, living these plural worlds is a political act – you decide who you bring into life – which worlds get noticed in your making – which realities gain credence – and which are ignored, trampled, subjugated. This is cosmopolitics. The politics of the cosmos.

Wait, who decides?

Things do. And we’re things. So we do. Jamie, Scott, me, are each worlding different worlds – attempting to gain access to a different politics. We are the virus.

But neither of them, of us, did it alone. We all constitute each other. Viruses and all got this going.

You might be waiting for the big reveal of why I keep repeating we are the virus. There’s no reveal, I’m afraid. But there is this dual thing going on. She said we are the virus. And in its context, it was a practice of speech that worlded a particular world at the very same time in which it relied on a particular world. There are far right politics to the we are the virus idea. Not Jamie’s idea – that we are literally viruses – but the idea that a mass ‘we’ of humanity can be grouped together and viewed in a negative way in terms of using Earth as a host. It implies a certain misanthropy, one that views over-population of non-white others as the primary environmental problem (I also don’t think she has far right leanings). It also implies a pristine body of Earth. A transcendent nature to which we are mere visitors – at least some of us. It’s a certain political ecology, among and within a multiplicity of political ecologies. An ecology of political ecologies. A practice of the natural that wraps up ideas of the social, and vice versa. Thinking with Scott, I like the idea of political ecologies as lines of movement. Jostling, fusing, speeding in and out of life through worldly practices of being. Knotting under tension. Appeals to the natural tangle within both egalitarian and far-right politics. For instance, there is a capitalist far-right ‘conspirituality’ (Ward & Voas, Reference Ward and Voas2011) seeping into/out-of online wellbeing influencers who promote ‘wellness, natural health, and organic food’ alongside a world where ‘big Science is evil, supplements help, you can boost your immune system, vaccines don’t work…’ (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2021). This view is not only difficult for appeals for mask wearing, social distancing, and vaccination, it also has a conspi-racist aspect. While cosmopolitics makes us aware that practices pluralise the cosmos in these sometimes difficult ways, it also means taking these multiple practices seriously – handling them with a sort of serious care and attention, whether they are the coming into being of viruses, a Scots pine or a wellness influencer. This is not the same as tolerance, it is instead creating spaces for the gathering, which circumvent the damage of modernist critique (Latour, Reference Latour2004; Stengers, Reference Stengers2008). One way to do this is through immanent, or creative critique, in the performance of alternative practices and worlds.

I think posthuman political ecology is what is going on constantly in the play of a life. These political ecologies infuse our writing in environmental education research all the time, whether we know it or not. So how do we tangle with political ecologies? Who/what/when/where/which gets to count? We don’t have mastery in deciding here – we can’t know what driving lines move through us – we can’t know what we don’t know or practice what we haven’t already practised – we aren’t in control of what happens to us. Really, we are the happening to us, with everything else. This isn’t space to tweak, just space to follow what you find coming up for you, with you, of you, as you (the bundle, spreading, knotting, untangling) continue along the lines. This. This writing, is what I’ve found myself doing. The track I’m following (Scott). I had a say in it, but it was really a conversation that got me/us here. And I’m not trying to sound grand, I don’t think we’ve/I’ve arrived (here) anywhere particularly impressive!

It was a throw away phrase, but it might seal up a world, unless we open it up. We are the virus.

My colleague is walking over to us as we look at the shallow ditch. Our group has taken longer than his to finish our liminality trail. My gaze falls to the copper light spilling through the golden huddle of Scots pine behind him. Wait, what worlds am I wording?

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Scott Jukes is a lecturer in Outdoor Environmental Education at Federation University, Australia. He has a passion for the river, mountain and coastal environments of south-eastern Australia and enjoys journeying and teaching in these places. His research explores pedagogical development and experimentation for outdoor environmental education, inspired by posthuman and new materialist theories. He is particularly interested in ways we may challenge human exceptionalism and rethink ontological assumptions as a response to our ecological predicament.

David A. G. Clarke is a Teaching Fellow in Outdoor Learning and Sustainability Education at the Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh (UK). He is based in the Outdoor and Environmental Education section of the Institute for Education, Teaching, and Leadership and is a member of the University’s Centre for Creative-Relational Inquiry (CCRI) and the Edinburgh Environmental Humanities Network. His teaching and research interests focus on transdisciplinary areas of creative inquiry, life experience, and ethics in education in the Anthropocene.

Jamie Mcphie is course leader for the MA in Outdoor and Experiential Learning at the University of Cumbria (UK) where he is an active member of the Centre for National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA). His teaching and research interests centre around tackling social and environmental inequities spread over varied terrains of thought-practice. His most recent publications include a joint (with Dave) guest edited Special Issue of Environmental Education Research focusing on new materialisms and environmental education and the book Mental health and Wellbeing in the Anthropocene: a posthuman inquiry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), which has a nice cover.