Around one in seven (13.9%) children and adolescents aged 4–17 years in Australia experience some form of mental health issue. This is equivalent to an estimated 560,000 Australian children and adolescents (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Johnson, Hafekost, Boterhoven De Haan, Sawyer, Ainley and Zubrick2015). At school, these students are frequently labelled as having an emotional or behavioural disability, but the reality is they often have complex support needs that go beyond just mental health. Students with complex support needs often experience two or more of the following: (a) mental health issues, (b) cognitive disability, (c) physical disability, (d) behavioural difficulties, (e) family dysfunction often resulting in involvement with out-of-home care or juvenile justice, (f) social isolation, (g) drug or alcohol misuse, or (h) early disengagement from education (Dowse et al., Reference Dowse, Cumming, Strnadová, Lee and Trofimovs2014). Typically, students with complex support needs are involved with a variety of agencies that rarely communicate with each other, resulting in both gaps and overlaps in support (Cumming et al., Reference Cumming, Strnadová and Dowse2014). The idea of integrated service models arose in the 1970s in the United States, with a focus on school-based wraparound models, as education was the sector that children and young people typically had the most contact with.

Wraparound, defined as a process of coordinated service provision, focuses on the practical implementation of case management in service provision (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Poland, Rozalski and Skiba2017). Over time, wraparound has become a generic term used to describe various multiple service delivery systems designed to address the complex support needs of young people and their families and has moved beyond the original medical-based model. Wraparound provisions have become acknowledged as potentially offering both ‘informal’ and ‘formal’ supports. Informal supports include persons important to the individual, such as family, friends, schoolteachers, and coaches of sporting teams. Formal supports are professional service providers and include psychologists, psychiatrists, special educators, counsellors, social workers, mental health workers, and providers of medical services. Formal supports may be based within (school based) or externally (school linked) to schools. Wraparound coordinators may be employees of the school system or of external agencies.

The wraparound process for an individual consists of four phases: (a) engagement and team preparation, (b) initial plan development, (c) plan implementation and development, and (d) transition. The process is developmental and activities characteristic of each phase have been identified (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Kerns, Lyon, Bruns and Cosgrove2010). The concept of wraparound has broadened over time, however, and practices have become diverse. Bruns et al. (Reference Bruns, Suter and Leverentz-Brady2008) developed the 11 principles of authentic wraparound to clarify the use of the term. These include (a) family voice and choice, (b) team-based planning, (c) use of natural supports, (d) collaboration, (e) community-based, (f) culturally competent, (g) individualised, (h) strengths based, (i) flexible resources, (j) unconditional care, and (k) outcomes based.

Wraparound in the Context of Site-Based Education

One of the most prevalent evidence-based practices in the education literature relating to behaviour is the positive behavioural interventions and supports framework. Positive behaviour interventions and supports consist of three tiers of intervention. Tier 1 interventions are intended to support the majority of the student population (80%) and consist of universal practices that are implemented throughout the school in all settings. Tier 2 interventions support the 15% of students who are determined to be at risk and are focused on rapid responses and high efficiency. Tier 3 interventions are designed to address the serious and ongoing emotional and behavioural problems of a small minority (1–5%) of students (OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, 2015). Interventions at this tier are individualised. Formal wraparound provisions can be an essential component of this third tier (Bruns et al., Reference Bruns, Duong, Lyon, Pullmann, Cook, Cheney and McCauley2016; Eber et al., Reference Eber, Hyde and Suter2011). Together with the response to intervention framework (O’Connor & Sanchez, Reference O’Connor, Sanchez, Kauffman and Hallahan2011) and complementary to multiple systemic therapy (Fuchs & Deshler, Reference Fuchs and Deshler2007), formal wraparound provisions with interagency approaches are a logical extension to provisions already provided by schools.

School-based wraparound initiatives are focused on improving educational achievement by addressing the support needs of the whole student. At a full-service school, wraparound services may be school based or school linked. In school-based wraparound, the services are on site and the school takes on the coordinating role with day-to-day management of the physical space and the responsibility of engaging and organising formal agency supports. Integrated services provided on site have been found to be desirable, as this circumstance assists in the creation of a community and culture of collaboration between school personnel, community agencies, parents, and students intended to promote student mental and physical health and academic success (Caldas et al., Reference Caldas, Gómez and Ferrara2019). School-linked wraparound services may or may not be on site; the school is an important collegial partner, but it may share the role of lead agency with another core community-based agency (Sather & Bruns, Reference Sather and Bruns2016). Sather and Bruns (Reference Sather and Bruns2016) conducted a survey to determine the extent of wraparound implementation in the United States and implementation supports that have been employed. Although this provided helpful information, more insight into the effectiveness of wraparound was needed.

Through an exploration of peer-reviewed articles, the current systematic review aimed to examine the current evidence base (2009–2019) for the effective provision of wraparound services in supporting school-age students with complex support needs. Specifically, answers were sought to the following research questions relating to the provision of wraparound services offered to school-age children and young people with complex support needs:

-

1. What evidence exists regarding the efficacy of formal wraparound services employed with school-aged students with complex support needs?

-

2. What are the barriers and enablers of effective school-based or school-linked wraparound models in providing integrated wraparound services for students with complex support needs?

Methods

Criteria

The criteria were established for the inclusion articles in the review. Articles had to be written in English, peer reviewed, and published between 2009 and 2019, as the field is evolving and the literature quite extensive. Publications of the last decade would identify current trends and still capture older relevant work through meta-analysis or systematic reviews. The focus of the articles had to be on children and/or young people aged 5–18 years with complex support needs attending an educational institution, and articles had to report on or describe collaborative planning for students with complex support needs attending school. The support team described must have included formal support professionals external to the school but operating within a school-based or school-linked program. This criterion ensured the possibility of authentic wraparound.

Many systematic reviews have restricted inclusion of articles to randomised, controlled studies when addressing the effectiveness of an intervention. However, when there are few relevant controlled studies identified, such restricted eligibility may force an unnecessarily conservative conclusion that evidence is insufficient to make any definitive statements. The value of considering alternative study designs is that they may capture important information that is otherwise lost (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Fink and Slutsky2005). For example, without this restriction the review article of Bertram et al. (Reference Bertram, Suter, Bruns and O’Rourke2011) identified a total of 118 publications spanning the years 1987–2008 that were relevant to wraparound implementation research, whereas the article by Suter and Bruns (Reference Suter and Bruns2009) that compared the effects of wraparound practices on young people (aged 3–21 years) compared with a matched control group identified only seven controlled studies from the same time period. To overcome an anticipated lack of controlled studies that met all criteria for inclusion in this systematic review, but also to avoid losing potentially valuable information relevant to the research questions, we decided to compromise and to only eliminate any articles that were not peer reviewed.

Search Strategy

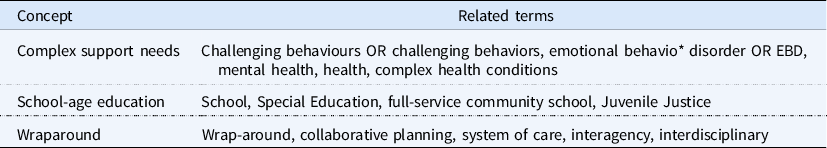

The databases searched during May–June 2019 for relevant sources were PsycINFO, ERIC, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar. The search focused on three major constructs represented in the research questions, those of ‘complex support needs’, ‘school-age education’, and ‘wraparound’. All are broad concepts and were searched using various related terms, as shown in Table 1. By examining the reference lists of the most recent relevant articles, and several current dissertations, the process of chaining was used to locate further articles.

Table 1. Search Terms

Examples of Database Searches

Searching PsycINFO with ‘challenging behavio*’ OR health AND (school OR special education OR juvenile justice) AND (wraparound OR wrap OR interagency OR system of care OR collaborative planning) produced 64 hits, of which 12 appeared to meet the criteria. When the search was repeated with EBD used as the Concept A term, from 69 hits, 18 more potential sources were identified. A similar search on the ERIC database yielded 75 hits, of which 26 were noted for further consideration. MEDLINE produced three hits to be further investigated. Keyword searches on Google Scholar produced approximately 1,500 hits, of which 103 were identified for further review. The inclusion of ‘health’ as a keyword provided some valid but many invalid hits, and was not always used. Other combinations of terms from each concept yielded further possible articles, and the process of chaining yielded 17 other potential sources not otherwise identified.

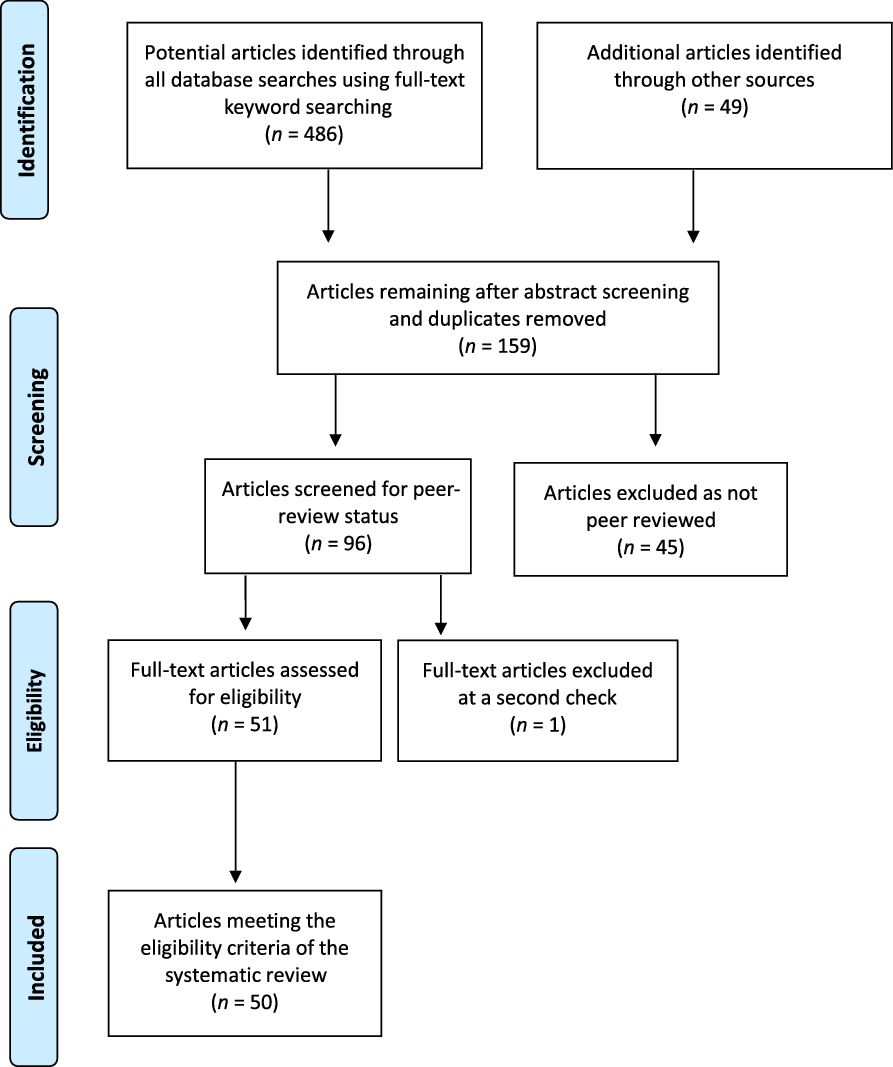

Figure 1 is an adapted form of a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) showing the different stages of the search process. Likely sources were identified through full-text keyword search, with limitations of date (2009–2019) and English language. Titles and abstracts of these sources were examined closely by the first author for relevance. To qualify for consideration, the source needed to reference the main concepts (children and/or young people aged 5–18 years with complex support needs attending school and reporting or describing collaborative planning for those students).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Representing the Strategy Used in the Literature Search.

The keyword search of the full articles identified in this manner resulted in 159 potential sources, but a quick scan of the title and abstract led to many eliminations, most commonly because the articles focused on wraparound use in mental health or child welfare with mention of schools or education. These were checked by the third author, who agreed with the first, resulting in a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 1.0, and leaving 96 articles that were further screened for eligibility based on being peer reviewed, leading to a count of 51 articles. These articles were then checked by the third author and, through consultation, one further article was excluded. This strong level of agreement resulted in a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 0.92. At the end of the process, 50 articles were identified as meeting the criteria. An annotated table of these articles can be found in the Appendix (see supplementary material).

Analysis

The full text of each article was carefully examined to locate material relevant to the two research questions, and results are reported in relation to each question. Particular attention was paid to implementation and results sections. Inductive content analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was used to analyse each article. All articles were read at least three times; the initial reading aimed to get understandings about the contents of the articles, a subsequent reading was used to code articles inductively according to each research question, and then a final reading was conducted to review and revise the codes. The first author made a table and inserted initial codes and relevant statements about wraparound efficacy and implementation from the articles. Then, the first author read through the codes and sorted the different codes into categories. The third author checked those initial codes and verified whether the codes appropriately fit in each category. After identifying codes and categories, the first author found the relationships among codes and categories and developed themes conceptualising the efficacy of wraparound and barriers and enablers to its provision. The third author checked these themes to verify their appropriateness. There was a strong level of agreement, resulting in a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 0.92. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion.

Results

Analysis of Articles in Relation to Question 1

To answer the first question, articles were examined to find evidence regarding the efficacy of wraparound services employed with school-aged students with complex support needs.

Controlled Studies

In the four controlled studies identified, assessments were found to relate to two broad areas: academic performance and behaviour. Two of the studies reported an advantage in academic performance in favour of students who received wraparound services, with one reporting a small effect size (Caldas et al., Reference Caldas, Gómez and Ferrara2019) and the other a moderate effect size (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Kerns, Lyon, Bruns and Cosgrove2010). A third study (Biag & Castrechini, Reference Biag and Castrechini2016) found no relationship between receiving support services and academic achievement.

Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Kerns, Lyon, Bruns and Cosgrove2010) found that there was no relationship between wraparound use and discipline incidents, another (Malloy et al., Reference Malloy, Sundar, Hagner, Pierias and Viet2010) found participation in a wraparound program had a moderate effect size (ES = .44) on behavioural functioning, and a third (Biag & Castrechini, Reference Biag and Castrechini2016) linked use of support service wraparound to a significantly negative difference in attendance rate.

In summary, the small number of controlled studies analysed (n = 4) tended to support similar studies conducted prior to 2009 of various outcomes of wraparound provision. Suter and Bruns (Reference Suter and Bruns2009) reported on seven studies that gave a mean effect size of 0.33 across all outcomes. There are indications that overall wraparound services may have a small to moderate positive treatment effect on school-attending children and young people with complex needs in improving academic performance and school-related functional behaviours. However, findings varied a great deal, and it is not possible to reach any conclusions from this small number of disparate studies. The greater number of non-controlled studies was then examined.

Non-Controlled Studies

Common to these studies was that no statistical comparison was provided with a matched control group. These studies were also very varied in purpose, participant number, outcomes, methodology, and in reporting of findings. In most cases, surveys, school records, and structured interviews were the data sources. Findings are reported from studies focused on targeted populations (e.g., school-age students with emotional and behavioural disorders [EBD] in mainstream schools, transitioning from psychiatric hospitals or juvenile correction centres) or site-based studies (e.g., community and mainstream schools with wraparound programs).

Outcomes reported from the 46 articles that were not controlled studies were found to relate to eight broad wraparound areas: (a) effect on academic performance (n = 6), (b) effect on school-related behaviours (n = 12), (c) stakeholders’ perceptions of efficacy (n = 9), (d) program model efficacy (n = 12), (e) leadership (n = 7), (f) interagency collaboration (n = 7), (g) transitions from most to least restrictive environment (n = 5), and (h) alternative education settings (n = 3).

The first two areas mirror those of the controlled studies, with the others giving an indication of the diversity of outcomes addressed in the identified articles. Some articles included no material relevant to this question, and others reported on more than one area, hence N does not equal 50. Each of these broad areas will be discussed in turn.

Effect on academic performance

Of the six studies, only the oldest (Eber et al., Reference Eber, Hyde and Suter2011; Kutash et al., Reference Kutash, Duchnowski and Green2011) found a significant increase in academic performance. The other four studies (2016–2018) were more cautious in their conclusions, reporting that only positive effects were found. These results mirrored those of the controlled studies, in that they were inconsistent but tended to show that wraparound had a potentially positive effect on academic performance.

Effect on school-related behaviours

All 12 articles reporting on behaviours provided evidence of improvement. The specific school-related behaviours investigated were school functioning (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011; Shailer et al., Reference Shailer, Gammon and de Terte2013), absenteeism (Anderson-Butcher et al., Reference Anderson-Butcher, Paluta, Sterling and Anderson2018; McKay-Brown et al., Reference McKay-Brown, McGrath, Dalton, Graham, Smith, Ring and Eyre2019), office discipline referrals (Anderson-Butcher et al., Reference Anderson-Butcher, Paluta, Sterling and Anderson2018; Eber et al., Reference Eber, Hyde and Suter2011), school placement failure (Eber et al., Reference Eber, Hyde and Suter2011; Test et al., Reference Test, Fowler, White, Richter and Walker2009), disruptive behaviour (Puddy et al., Reference Puddy, Roberts, Vernberg and Hambrick2012), reduction in juvenile justice involvement (Shailer et al., Reference Shailer, Gammon and de Terte2013), and frequency of community agency referrals for families (Test et al., Reference Test, Fowler, White, Richter and Walker2009). Articles also referred to studies that asserted that school wraparound practices led to students experiencing reduced mental health needs (Effland et al., Reference Effland, Walton and McIntyre2011; Fallon & Mueller, Reference Fallon and Mueller2017; Painter, Reference Painter2012; Shailer et al., Reference Shailer, Gammon and de Terte2013), improvement in adaptive functioning (Fries et al., Reference Fries, Carney, Blackman-Urteaga and Savas2012; Puddy et al., Reference Puddy, Roberts, Vernberg and Hambrick2012), and progress in increasing social interaction with peers and more positive experiences at school (McKay-Brown et al., Reference McKay-Brown, McGrath, Dalton, Graham, Smith, Ring and Eyre2019). Several studies indicated that the length of time the student had been receiving wraparound services determined the success of the intervention (e.g., Anderson, Reference Anderson2011; Painter, Reference Painter2012; Puddy et al., Reference Puddy, Roberts, Vernberg and Hambrick2012).

Stakeholders’ perceptions of efficacy

Stakeholders involved in the wraparound process were case managers or facilitators, school administrators, probation officers, counsellors, psychologists, teachers, school-based mental health providers, and community school coordinators. Interview methodology was employed in nine studies, three were multiple case studies, two used a mixed method, two included focus groups, and one incorporated direct field work. Stakeholders reported that the wraparound model (a) increased family support and engagement with the school (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Chen, Min and Watkins2017; Senior et al., Reference Senior, Carr and Gold2016); (b) significantly improved school climate (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Chen, Min and Watkins2017; Anderson-Butcher et al., Reference Anderson-Butcher, Paluta, Sterling and Anderson2018); (c) resulted in more school–community partnerships (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Chen, Min and Watkins2017); and (d) enabled more positive transitions from juvenile justice or hospital (Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017).

One of the most frequently cited barriers to wraparound success was the low competency of the facilitator or case manager (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Houser and Howland2010; Bartlett & Freeze, Reference Bartlett and Freeze2018; Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017). Other studies indicated there was a lack of commitment of adult stakeholders (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Houser and Howland2010) or a school culture that did not reflect a child-centred and strength-based philosophy (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Houser and Howland2010; Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017). The absence of resources such as school-based mental health services and a lack of support for collaborative practice at school, systems, and government levels were also identified as barriers (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Houser and Howland2010; Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2018; Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017). The other two factors mentioned were a lack of agency partners in remote areas and a lack of adequate outcome-based measures (Bartlett & Freeze, Reference Bartlett and Freeze2018).

Program model efficacy and leadership

Anderson (Reference Anderson2016) and Bartlett and Freeze (Reference Bartlett and Freeze2018) noted the difficulties in finding valid ways to measure wraparound. Kazak et al. (Reference Kazak, Hoagwood, Weisz, Hood, Kratochwill, Vargas and Banez2010) asserted that wraparound efficacy could be enhanced by longitudinal assessment of relevant aspects of students’ lives. Kutash et al. (Reference Kutash, Duchnowski and Green2011) skirted these issues by directly comparing the efficacy of four different school-based mental health models in terms of outcomes and found the integrated wraparound model superior in increasing emotional functioning, decreasing functional impairment, and increasing school attendance.

Some researchers considered wraparound within a systems-based approach or within the context of other models. Fallon and Mueller (Reference Fallon and Mueller2017) considered wraparound as part of an ecological system, emphasising that efficacy increased when culturally responsive integration extended across components. Bartlett and Freeze (Reference Bartlett and Freeze2018) found that the community school model aligned well with the principles of wraparound, and Charlton et al. (Reference Charlton, Sabey, Dawson, Pyle, Lund and Ross2018) suggested that an integrated system of positive behavioural interventions and support, response to intervention, and Tier 3 wraparound was a model that offered many benefits. Kern et al. (Reference Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Poland, Rozalski and Skiba2017) cited evidence that having a mental health centre integrated into the school increased the efficiency of wraparound by increasing accessibility to essential services.

Anderson (Reference Anderson2016) observed that for a model to be efficacious, relationships are key and politics inescapable. These observations are backed up by Sanders’s (Reference Sanders2016) findings concerning leadership style and the importance of the development and maintenance of relations with partners. Anderson’s claim that at least 5 years needed to elapse before program effectiveness can be evaluated is supported by other researchers (Fries et al., Reference Fries, Carney, Blackman-Urteaga and Savas2012; Puddy et al., Reference Puddy, Roberts, Vernberg and Hambrick2012).

Interagency collaboration and transitions from most to least restrictive environments

This form of wraparound has additional elements related to transitioning from a regulated environment, such as a hospital or juvenile justice centre, back into the community and mainstream schooling. Three of the five included articles referred to transition from juvenile justice facilities (Coldiron et al., Reference Coldiron, Bruns and Quick2017; Nisbet et al., Reference Nisbet, Graham and Newell2012; Strnadová et al., Reference Strnadová, Cumming and O’Neill2017), one from hospital (Savina et al., Reference Savina, Simon and Lester2014), and one from either (Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017). Coldiron et al. (Reference Coldiron, Bruns and Quick2017) reported on a controlled study (Carney & Buttell, Reference Carney and Buttell2003, as cited in Coldiron et al., Reference Coldiron, Bruns and Quick2017) that found that the provision of wraparound services was significantly more successful than referral to agencies in isolation, in terms of school attendance and improved pro-social behaviours. Nisbet et al. (Reference Nisbet, Graham and Newell2012) reported collaborative teamwork improved the attitudes of external agencies towards juvenile justice. However, this collaboration was found to be complex and demanding of time and resources, with problems of cross-disciplinary communication and information sharing (Strnadová et al., Reference Strnadová, Cumming and O’Neill2017). Savina et al. (Reference Savina, Simon and Lester2014) noted that fewer than half the special education teachers in schools received any communication regarding children returning from a more restrictive environment, and this made it more difficult to organise wraparound. Wraparound was found to be more successful for transitioning youth if there was (a) consistency and continuity between environments with reliable support provision; (b) gradual, smooth change; (c) good interagency communication; (d) youth and family participation in the plan; (e) discharge planning that began immediately upon admission; and (f) positive attitude of the school towards the returning student (Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017; Strnadová et al., Reference Strnadová, Cumming and O’Neill2017).

Analysis of Articles in Relation to Question 2

To answer the second research question, all articles were examined for references to barriers and enablers that impacted the effective provision of school-based wraparound. The analysis led to the identification of nine main areas where barriers and enablers were reported; these are discussed as follows.

Wraparound team functioning

Effective interagency collaboration received the most attention in the identified literature. Most researchers noted the need for external agencies to work in a multisystemic, collaborative manner. External agencies have traditionally operated as ‘silos’ (Biag & Castrechini, Reference Biag and Castrechini2016), infrequently partnering with schools (Coldiron et al., Reference Coldiron, Bruns and Quick2017). Effective wraparound teams build shared expectations and agendas that result in all having similar priorities (Weist et al., Reference Weist, Mellin, Chambers, Lever, Haber and Blaber2012) and accepting shared responsibility for outcomes (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2018). Interpersonal relations between the team members ideally reflect understanding, trust, and flexible cooperation, undamaged by any potential power imbalances within and between stakeholder groups (McLean, Reference McLean2012).

Information sharing was also considered an important enabler of collaborative service provision. Researchers found that unwillingness to share information often originated from a sense of responsibility to maintain the privacy of the student (Strnadová et al., Reference Strnadová, Cumming and O’Neill2017; Thielking et al., Reference Thielking, Skues and Le2018). Furthermore, differences in priorities and protocols commonly existed between the agencies, acting as barriers to understanding the relevance of available information, and differences in everyday data systems resulted in difficulties in the sharing of information (McKay-Brown et al., Reference McKay-Brown, McGrath, Dalton, Graham, Smith, Ring and Eyre2019). Higher levels of collaboration were achieved by regular team reflection and evaluation of processes. It was noted that time must be set aside on a regular basis for this team activity (Mellin et al., Reference Mellin, Anderson-Butcher and Bronstein2011; Weist et al., Reference Weist, Mellin, Chambers, Lever, Haber and Blaber2012). Golding (Reference Golding2010) asserted that team member commitment was a major enabler to the wraparound process.

Funding

Funding was commonly acknowledged as a necessity to wraparound success. Resource requirements ranged from generalised funds for trained personnel to perform specific functions (Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Sabey, Dawson, Pyle, Lund and Ross2018; McLean, Reference McLean2012), funds for suitable and compatible data systems (Anello et al., Reference Anello, Weist, Eber, Barrett, Cashman, Rosser and Bazyk2017), and funds to buy the time required to implement an effective wraparound process (Maximoff et al., Reference Maximoff, Taylor and Abernathy2017). Funds were noted as coming from various sources such as school system allocations; local, state, and federal grants; health agencies; and fee-for-service mechanisms (Weist et al., Reference Weist, Mellin, Chambers, Lever, Haber and Blaber2012).

Leadership

Leadership of principals, wraparound facilitators, and participating partnerships were all considered significant to the success of the wraparound process. Facilitator leadership received the most mention (n = 12), followed by that of principals (n = 8), and leadership within external partners (n = 3). Principal leadership was recognised as significant in building the infrastructure within schools to develop and support any form of wraparound (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Poland, Rozalski and Skiba2017). Wraparound facilitators in school-centric models serve as the ‘linchpin’ in providing services to students in need (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Owens and Bartlett2015). A strong facilitator acts to coordinate services, enhancing the effectiveness of wraparound services (Puddy et al., Reference Puddy, Roberts, Vernberg and Hambrick2012). Several authors asserted that the school psychologist or the school mental health worker would be the logical person to take on this leading role (Hess et al., Reference Hess, Pearrow, Hazel, Sander and Wille2017; Mellin et al., Reference Mellin, Anderson-Butcher and Bronstein2011; Thielking et al., Reference Thielking, Skues and Le2018). However, Farmer et al. (Reference Farmer, Sutherland, Talbott, Brooks, Norwalk and Huneke2016) believed that special educators trained in the area of students with EBD may best fill this role. Senior et al. (Reference Senior, Carr and Gold2016) described the advantages of the facilitator being a family social worker, as they can best coordinate the services across the school, families, and external agencies.

Program design

Many barriers to effective wraparound were noted in the design and implementation of the program. Kern et al. (Reference Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Poland, Rozalski and Skiba2017) examined the effects of which stage (preventive or interventionist) students were asked to engage with the program (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Poland, Rozalski and Skiba2017) and for how long (Fries et al., Reference Fries, Carney, Blackman-Urteaga and Savas2012). Golding (Reference Golding2010) suggested that in order to be successful, the program had to fit the local context and be responsive to individual needs (Golding, Reference Golding2010). This included cultural appropriateness and cohesion across components of the student’s ecosystem (Leonard, Reference Leonard2011), particularly to minority students (Fallon & Mueller, Reference Fallon and Mueller2017; Kern et al., Reference Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Poland, Rozalski and Skiba2017). Programs were more successful when there was continuity of the support personnel during (Senior et al. Reference Senior, Carr and Gold2016) and after the wraparound intervention (Ungar et al., Reference Ungar, Liebenberg and Ikeda2014). Lastly, the most successful wraparound programs had included student, family, and teacher involvement in wraparound planning and processes (McKay-Brown et al., Reference McKay-Brown, McGrath, Dalton, Graham, Smith, Ring and Eyre2019).

Stakeholder buy-in

All the reviewed articles discussed the importance of the commitment of stakeholders and its enabling or disabling effect on program effectiveness. Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Chen, Min and Watkins2017) noted strong leadership from the principal but barriers to teacher buy-in. Other barriers included lack of teacher awareness of student needs, diversity of teacher expectations, and teacher burnout (Anderson-Butcher et al., Reference Anderson-Butcher, Paluta, Sterling and Anderson2018). Some teachers lacked buy-in because they felt overwhelmed by the breadth of wraparound services and had not experienced any training prior to the implementation of a wraparound model. Others believed that teaching and learning would be compromised by devoting time and resources to a wraparound model (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016).

Wraparound principles include families/caregivers as an essential support for students (Bruns et al., Reference Bruns, Suter and Leverentz-Brady2008), and buy-in critically involves the family as a whole unit (Senior et al., Reference Senior, Carr and Gold2016). Without this support, students are not likely to cooperate with the program or will quickly disengage. The family provides potential links to the local community (e.g., relatives, church, clubs and sporting groups) that can provide the informal support required for students both during and after the wraparound intervention (Shailer et al., Reference Shailer, Gammon and de Terte2013). The absence of an individualised community network acts as a considerable barrier to the efficacy of wraparound.

Turnover/Absentee rates of stakeholders

Turnover among school leaders (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016; Anderson-Butcher et al., Reference Anderson-Butcher, Paluta, Sterling and Anderson2018; Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2018) and personnel in schools and supporting agencies (Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Sabey, Dawson, Pyle, Lund and Ross2018) creates instability that can hinder the effective implementation of wraparound. Further barriers include student absenteeism (Bruns et al., Reference Bruns, Duong, Lyon, Pullmann, Cook, Cheney and McCauley2016) and high dropout rates (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016). The same issues of turnover and absenteeism result from changes in staff at the state and national level, where different personnel had different understandings and priorities and have the power to withdraw support and funding (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016; Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Sabey, Dawson, Pyle, Lund and Ross2018).

Formalised role descriptions

An effective collaborative team has a shared understanding of member roles (Thielking et al., Reference Thielking, Skues and Le2018) and is prepared to take shared responsibility (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2018). As interdisciplinary team members are disparate in their goals and beliefs, clear understandings and explicit communication is essential. Unforeseen barriers that may become obvious during implementation are a lack of professional competency of school or agency team members or a lack of skill in interagency collaboration (Eber et al., Reference Eber, Hyde and Suter2011; Savina et al., Reference Savina, Simon and Lester2014; Weist et al., Reference Weist, Mellin, Chambers, Lever, Haber and Blaber2012). These barriers could be overcome, however, with adequate professional development.

Readiness and implementation practices

The four stages of implementation of wraparound have been described as contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (Effland et al., Reference Effland, Walton and McIntyre2011). The implementation process is lengthy and resource intensive (Fallon & Mueller, Reference Fallon and Mueller2017). The delivery of professional development throughout implementation is a major enabler of the success of wraparound. Training in principles and practices is essential for staff and students (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Houser and Howland2010) and cross-agency training is particularly important for wraparound team members (Mellin, Reference Mellin2009; Strnadová et al., Reference Strnadová, Cumming and O’Neill2017). A great deal of effort is needed to establish effective wraparound (Anderson-Butcher et al., Reference Anderson-Butcher, Paluta, Sterling and Anderson2018) and schools vary in their degree of readiness to implement wraparound. A high level of buy-in by stakeholders, adequate resources, and a great deal of preliminary effort will enable success (Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Sabey, Dawson, Pyle, Lund and Ross2018).

Communication issues

Good communication is paramount in any team-based collaboration. In wraparound programs, communication is crucial at multiple levels. For example, facilitators must communicate effectively with team members, external agencies, community supports, parents, and students (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Chen, Min and Watkins2017). School leaders interact with the community, families, and the wraparound team. Effective communication between team members is particularly enabling for wraparound, as collaboration relies on the ability to connect with each other through words and actions across boundaries that have traditionally defined disciplines (Shailer et al., Reference Shailer, Gammon and de Terte2013). Teams need to build a consistency of terminology (Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, Sabey, Dawson, Pyle, Lund and Ross2018), and a workable compatibility in philosophical orientation, goals, and practices across all professional partners in the team. This is enabled through ongoing team discussion, reflection, and, most likely, some degree of compromise.

Discussion

Although there was some evidence of positive effects of wraparound on academic performance, particularly in the long term, evidence was strongest for the improvement of school-related behaviours. The length of intervention and the fidelity of the wraparound program were found to be key. All stakeholders were overwhelmingly positive and optimistic concerning the efficacy of school-based wraparound, although most reports were through semistructured interviews, anecdotal more often than data based, and may reflect an investor bias. In many of the articles, stakeholders also indicated significant barriers to the efficacy of the wraparound model.

Because of its complexity and differing manifestations, the efficacy of the total experience of the wraparound process is difficult to assess. Wraparound is described in terms of a standalone process, an ecological model, an extension of intervention processes in schools, and a guiding principle in community schools. The consensus is that wraparound is efficacious if applied with fidelity over an adequate time period. Ungar et al. (Reference Ungar, Liebenberg and Ikeda2014) conducted extensive case studies of youth with complex needs who were multiple service users and summarised characteristics that make an efficacious wraparound intervention for school-age youth: (a) offered at different levels of intensity, (b) efficiently coordinated through collaborative teaming, (c) of an appropriate length, (d) negotiated with the student and family, (e) provided along a continuum from least to most intrusive, and (f) be evidence based.

The leadership style of both principals and facilitators has been shown to be tantamount to effective wraparound services. The background knowledge and expertise of the individual undertaking the facilitator role is acknowledged as central to a successful program, and special educators, school psychologists, school counsellors, school social workers, and family support workers have support for the role in the literature.

Interagency collaboration is acknowledged as an important factor in wraparound efficacy. The literature focused on reasons why collaboration has been ineffective, with poor information sharing and communication often creating problems. One study found that collaboration was more effective when wraparound was based in the school context.

The effects of wraparound in alternative education settings were found to be similar to those in mainstream schools. Observable improvements were seen in school-related behaviours and the maintenance of improvement depended on the length of the program and the intensity of the service provision. Students transitioning into the school from more restrictive environments were recognised as needing effective wraparound processes. This was reported as only coming about through strong interagency collaboration and substantial, meaningful, and timely communication between the institution and the receiving school so that appropriate support could be provided.

Barriers and enablers were at opposite ends of a factor continuum. Collaborative functioning of the wraparound team was the most commonly mentioned factor, with differences in culture, priorities, and protocols creating difficulties with communication and information sharing. The availability and commitment of professional partners willing to accept the workload of providing effective wraparound was also noted as an enabler to effective wraparound. The sourcing of adequate funding and resource allocation within the complex process of wraparound was noted as an important barrier or enabler.

Strong, effective leadership was considered paramount to wraparound success. Wraparound efficacy was also contingent upon program characteristics, such as program length, intensity of services, stage at which students participated, cultural appropriateness, consistency of personnel, engagement with the program, and care offered after exit. Six important stakeholder groups whose commitment was central to wraparound effectiveness included school principals, teachers and staff, participants and their families, the local community, external agencies, and relevant political systems.

Participant absenteeism and dropping out of the program were noted as having major effects on efficacy, as did changes among wraparound team members interacting with the student. Any lack of formal understanding between team members regarding goals, roles, and responsibilities was found to negatively impact wraparound effectiveness. Also noted were different degrees of professional competence in the ability to work as a team and to work with students with complex needs.

Conclusion

In the current review, we sought to map existing peer-reviewed literature on wraparound to determine the efficacy of wraparound for students with complex support needs, and what barriers and enablers were reported in the provision of wraparound services. Overall, results of the reviewed studies suggested that effective wraparound programs were more efficacious in improving student behaviour rather than academics. The inverse of most of the barriers identified were identified as enablers. Early planning, collaborative functioning of the wraparound team, availability and commitment of professional partners, and adequate funding/resources were all noted as important barriers and enablers.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2022.1