In a multi-racial and multireligious society like yours and mine, while we judges cannot help being Malay or Chinese or Indian; or being Muslim or Buddhist or Hindu or whatever, we strive not to be too identified with any particular race or religion – so that nobody reading our judgment with our name deleted could with confidence identify our race or religion, so that the various communities, especially minority communities, are assured that we will not allow their rights to be trampled underfoot. (Former Lord President Tun Mohamed SuffianFootnote 1 )

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the 1990s, as countries in Southeast Asia have become more democratic and more liberal, judges have become more deeply involved and more assertive in political matters. This trend towards the “judicialization of politics”—which Hirschl describes as “the ever-accelerating reliance on courts and judicial means for addressing core moral public policy questions, and political controversies”Footnote 2 —has been well documented elsewhere in the world,Footnote 3 but there is still a vigorous debate about what drives it in Asia and its effects there.Footnote 4 This is partly because courts there have behaved very differently from each other in constitutional matters: some have actively intervened to check executive abuse, uphold the supremacy of law, make governments more accountable, and protect the rights of citizens; others seem to have subverted the rule of law and undermined mechanisms of accountability on behalf of narrow interests; still others have simply avoided any engagement with political and constitutional governance issues.Footnote 5

The Federal Court of Malaysia (FC)Footnote 6 is a good illustration of some of these ambiguities. Its assertiveness in challenging the broader exercise of government power in high-profile cases has been far less consistent than that of counterparts in the region.Footnote 7 In fact, despite its growing engagement in areas ranging from electoral and religious disputes to civil liberties and executive prerogatives, for decades, its decisions in constitutional areas have vacillated widely. Notwithstanding the difficulty of assessing patterns of judicial assertiveness and restraint beyond decisions simply for or against the government,Footnote 8 observers of the Malaysian FC have used terms like assertiveness and restraint to describe the behaviour of the court over time. For instance, it is widely reported that, immediately after independence in 1957, judicial self-restraint and deference to legislative intent, supported by strict legalism, characterized most FC constitutional decisions.Footnote 9 By the 1980s, however, it had begun to review cases involving the government more vigorously, only to again become restrained during most of the 1990s and 2000s. Since then, however, the FC’s behaviour in constitutional matters has become less predictable—even erratic.Footnote 10

Accusations of executive meddling, political bias, and professional failings in Malaysian courtsFootnote 11 have regularly raised questions about how to understand what has been happening in the FC, the highest court, particularly in such vigorously contested constitutional areas as the “megapolitical” cases. In the last decade, the question has become even more urgent because political, social, and religious contestation has been rising in Malaysia’s complex multi-ethnic, multireligious society.Footnote 12 Moreover, the 2018 election ended six decades of dominant political rule by the Barisan Nasional (BN) party coalition, replacing it with the opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH) alliance. Yet increased political competition, and an uncertain transition marked by fragile political coalitions,Footnote 13 is also heightening the urgency for ensuring that Malaysia has an independent arbiter in constitutional matters.

To date, the question of how to evaluate the past behaviour of the Federal (formerly Supreme) Court of Malaysia, particular in high-profile cases, has generally had two types of answers: legal or political.

Legal scholars have generally taken a traditional view of the FC’s behaviour. For instance, while the Malaysian courts have long asserted the power to review statutes for their conformity with the Constitution, which sets out a number of justiciable rights, judges at all levels have been deferential: long-standing domestic practice has been strict legalism, marked by a narrow, formalistic review of the constitutional text. Since the 1960s, in interpreting the Constitution, the court has taken to looking only “within its own four walls;”Footnote 14 it has refused to engage with sources from comparative jurisdictions or international law principles.Footnote 15 It also defers to Parliament’s “legislative intent” and to “executive prerogatives”—though it has honoured the general common-law precedent that requires judges to explain how a decision conforms with previous ones or why they decided to overturn what had been binding precedent. There is also an occasional nod, though no real commitment, to a “basic structure” doctrine.Footnote 16 No wonder the Malaysian federal judiciary has been described as demonstrating “legal” or “pragmatic” conservatism.Footnote 17

Political scholars, however, have emphasized the unique political environment in which Malaysian courts have operated since independence. Describing the judiciary as at first highly independent and professional, these scholars stress how six decades of single-party dominance have eroded independence and changed how the courts operate. Over time, the executive grip on the courts was tightened by political leaders who lacked the legal background of the early independence generation.Footnote 18 For scholars of politics, a major factor in undermining the Supreme Court (SC), and later the FC, was the confrontational political stance of then-Prime Minister (PM) Mahathir (1981–2003). Besieged by financial scandals, political crises, and intra-coalition disputes within the United Malay National Union (UMNO),Footnote 19 in 1988, PM Mahathir turned on the SC. Coinciding with the possible deregistration of UMNO by a legal appeal to the SC, the political assault on the country’s top judges culminated in removal for misbehaviour of the Lord President of the Supreme Court and five of his colleagues through a special tribunal.Footnote 20 Institutional changes introduced under Mahathir limited judicial powers and there was growing evidence of political meddling in judicial appointments and high-profile political decisions.Footnote 21 Meanwhile, BN’s supermajority in Parliament was sufficient to drastically amend the Constitution.Footnote 22 Thus, the government could “retaliate to a robust judicial interpretation of the Constitution by deploying constitutional or unconstitutional means to discipline the courts.”Footnote 23 As will become evident, this seems to have been particularly true in times when the regime felt threatened by infighting or narrow election outcomes.

Though the legal and political explanations are complementary rather than mutually exclusive, in fact, since the mid-1980s, the FC has declared only three statutes unconstitutional and, of 17 cases of constitutional review, only six were ultimately upheld. But neither explanation tells us much about how judges themselves fit into the narrative (despite occasional claims of “originalist” and “revisionist” judges going toe to toe).Footnote 24 At best, both might support a “strategic” explanation of judicial behaviour: the judges may at times retreat to legal formalism simply to avoid being drawn into the political fray. At worst, this behaviour might evidence a judicial post-1988 capitulation, given politicized appointments and ideological capture of the courts, particularly the FC, by judges apparently acting in support of ruling coalition interests.

Declining public trust in the country’s courts,Footnote 25 regular outcries from within the legal complex about decisions in specific high-profile cases,Footnote 26 and occasional accusations by judges themselves of political meddling and stacking of the courtsFootnote 27 —all seem to support the view of judges as politically captured. Yet, for the last decade, the behaviour of the FC in high-profile cases has been highly inconsistent: it has occasionally made efforts to adjudicate rights claims using proportionality analysisFootnote 28 or to reassert its power in a reinvigorated interpretation of separation of powers as part of a basic structure under Article 121(1) of the Constitution.Footnote 29 The picture has thus become more complex, with new dynamics and even ideological battles unfolding within the top courts, if not the FC bench itself.

How well founded are the differing perceptions of the FC? What patterns of decision-making, if any, emerge in megapolitical cases and how have these changed over time? What factors other than the law might be influencing Malaysia’s judges in high-profile cases? These questions are particularly relevant now because the post-BN government has promised to rebuild trust in the judiciary as part of its commitment to institutional reformFootnote 30 and public demand is growing for judges who can be independent arbiters in an increasingly competitive political environment.Footnote 31

Unlike previous studies, we here apply an empirical methodology to the analysis of how FC judges make decisions by exploring the behaviour of the FC bench using an original data set, based on a stringent methodology for identifying megapolitical cases from 1960 through 2018. Following Ran Hirschl, we define as megapolitical those cases that go beyond issues of procedural justice and political salience to include “core political controversies that define (and often divide) whole polities.”Footnote 32 We supplemented the 102 cases identified with socio-biographic profiles of the 102 judges who served on the Supreme or Federal Court bench during this period. We then tested patterns of judicial alignment and dissent in the original data set to explore the extent to which the court has taken a counter-majoritarian role in Malaysia’s political system.

Our systematic analysis of descriptive data and the results of the regression analysis lend considerable support to theories about the declining independence and general politicization of the FC—measured narrowly here in terms of votes for and against the government in power.Footnote 33 While megapolitical cases have been trending up since 1960, though with distinct peaks, since 1988, it appears that the FC has been ever less inclined to decide against the government.

Equally interesting is the decline in dissents by members of the bench that has gone hand in hand with the decline in anti-government votes. While there is a rich scholarly literature on dissent and norms of consensus that highlights factors such as gender, ideology, and panel effectsFootnote 34 (we test for some of these), additional factors that seem particularly worth exploring for Malaysia relate to the fact that the bench has gradually become less diverse most clearly in the areas of overseas education, ethnicity, and religion. The lack of ethnic diversity at the FC is in stark contrast to the composition of the Court of Appeal and the High Court, Malaysia’s other superior courts. In fact, our inferential statistics show that ethnicity, votes by appointees of the PM, and above all appointments after 1988 are significant in explaining FC voting patterns, and may also affect a judge’s willingness to dissent.

The results are thus somewhat aligned with evolving public pessimism about the quality of the FC bench since 1988 and the degree to which it is representative, or impartial. Though our findings should be read with careful analysis of the context and content of each decision, we hope that, by providing the first systematic account of factors that go into FC decision-making, we can contribute to a better understanding of how Malaysia’s FC operates.

To fully clarify how FC judges behave, in Section 2, we address the court’s institutional background and historical performance. Section 3 briefly summarizes theories of judicial behaviour and the guiding hypothesis of the study, Section 4 describes the data set, followed by discussion in Section 5 of the empirical results. Section 6 sets out conclusions.

2. ESTABLISHMENT, POWERS, AND PERFORMANCE OF THE FEDERAL COURT OF MALAYSIA

The FC was established in 1957 when Malaysia became independent. Known from 1985 to 1994 as the Supreme Court, it once again became the FC through the Constitution (Amendment) Act in 1994, which also created a Court of Appeal. The FC, like the country’s court system as a whole, traces its common-law origins back to 1806 and the appointment of a magistrate in Penang. In 1826, the Second Charter of Justice in the Straights Settlements created the British colonial Court of Judicature; in 1946, the Malayan Union established a national judiciary; and, in 1956, the Civil Law Act formalized the country’s acceptance of common law. In 1957, the Federal Constitution elevated the judiciary to its present role as an independent branch of government. After final appeals to the British Privy Council in civil matters were abolished in 1985,Footnote 35 the FC, together with the Court of Appeal and the two high courts, became the peak of Malaysia’s three-tier system of superior courts and the judiciary was thus encouraged to chart its own independent path.

The superior courts adjudicate both state and federal disputes, with some exceptions for Syariah courts and those of Sabah and Sarawak. The Judicature Act 1964 (Act 91, revised 1972) grants the FC original, appellate, referral, and advisory jurisdiction. Though its work consists mainly of hearing civil and criminal appeals,Footnote 36 as the final appellate court in Malaysia, it has been in the “eye of the constitutional storm probably as often as the judiciary of any other country,”Footnote 37 because judicial review is also available for any actions, omissions, and decisions on the part of the executive or its delegates and, when the legislative branch has enacted ultra vires legislation—whenever it is alleged that behaviour contravenes the Federal Constitution—it is considered a constitutional challenge.Footnote 38

While these cases are usually brought in the High Court, the FC may become involved either because of (1) its exclusive, original jurisdiction under Article 128(1) when it is charged that Parliament or the state legislative assemblies had no powers to enact a given law; or (2) its appellate jurisdiction, where, except for criminal matters and specified subjects, aggrieved parties who meet stringent criteria can lodge applications (“leave” applications) for the FC to review Court of Appeal decisions for breaches of natural justice, the written law, and the Constitution.Footnote 39 In practice, in Malaysia, constitutional matters thus are rarely wholly separate from administrative law, criminal, or even property matters. Few cases have arisen on referral, which concerns the interpretation of any constitutional provision and which reaches the FC as a special caseFootnote 40 or because of its advisory jurisdiction under Article 130.Footnote 41 Footnote – Footnote 43

De jure, safeguards for independence are strong in both the Constitution (Part IX, Articles 121–131A) and in ordinary legislation. Because judges of the superior courts enjoy security of tenure and their salaries are charged against the Consolidated Fund, their salaries and such terms of office as pension rights cannot be altered to their disadvantage. The ability to discipline or dismiss judges is also limited. For instance, Parliament can only discuss the conduct of a judge on a substantive motion supported by 25% of all parliamentarians, and there can be no discussion at all in State Legislative Assemblies (Articles 125–127). Similarly, a judge can only be dismissed after an independent tribunal has established a breach in the code of ethics that may lead to sanctions, such as dismissal under Article 125(3).

The highly controversial 1988 dismissal by an independent tribunal of Malaysia’s top judges on grounds of breach of the code of ethics, followed by changes to Article 121(1), have, however, raised persistent concerns about how much independence Malaysian judges actually have. In fact, although, before 1988, Article 121 vested the judicial power of the Federation in the high courts and such inferior courts “as might be provided by federal law,” later amendments to that Article now state that the High Court, the Court of Appeal, and the FC have jurisdiction only as may be “determined by statute.” This has been widely perceived as preventing the judiciary from protecting its own power by defining that power and isolating it from statutory interventionFootnote 44 —a view the FC has not accepted.Footnote 45 Combined with a continuing practice of appointing judges to the High Court as judicial commissioners (often seen as a form of probation) and the lack of superior-court-type tenure arrangements for lower-court judges, there have long been concerns about how independent judges are from the administration. Under PM Badawi (2003–09), the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC), established in 2009,Footnote 46 was mandated to reinforce the integrity of the judicial appointments process, above all by identifying for the PM’s consideration judges qualified for appointment to the superior courts (e.g. High Court, Court of Appeal, FC). Judging by regular complaints about executive influence in promotions and about corruption and personal misconduct by judges, its success seems questionable.Footnote 47

The FC consists of at least 12 judges: its chief justice (CJ), the president of the Court of Appeal, the chief judges of the two high courts, and eight other judges appointed by the king, Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who in fact acts on the advice of the prime minister after consulting with the Conference of Rulers and (except for appointment of the CJ) with the Chief Justice. Article 122(1A) of the Constitution allows the king to increase the number on the FC bench.Footnote 48 A judge on the Court of Appeal may also serve on the FC in addition to the president when the FC Chief Justice considers that the interests of justice so require (Article 122(2)). And, while every FC proceeding is heard by at least three judges, normally five hear cases as a final Court of Appeal; in very rare and important cases—like the megapolitical cases considered here—the full bench is seven or more.

Qualifications for the bench are stringent. In addition to being vetted by the JAC, judges must have at least 10 years of experience as a judge, an advocate before the superior courts, or in the legal service; most FC judges have been career judges. FC judges are required to retire at 66 years and 6 months old.

Ever since 1988, there have been concerns about the inner workings of Malaysia’s courts, including the FC. Even judges have made accusations of judicial misconduct, corruption, and politicized promotions, as shown most recently by the affidavit filed by former Court of Appeal judge Hamid Sultan Abu Backer in 2019. There has also been evidence of political meddling in appointments (e.g. the Lingam Tapes in 2007)Footnote 49 ; abuse of due process in high-profile cases, most notably those involving the leader of the opposition, Anwar Ibrahim (e.g. Anwar Trials I and II)Footnote 50 ; and pressure exerted on judges in other religious cases (e.g. the Herald case).Footnote 51 Combined with unconstitutional political efforts in 2018 to extend the term of the CJ of the FC and the president of the Court of Appeals (CA) beyond the term limits,Footnote 52 it is not surprising that, over the years, criticism of the courts by the legal profession has been mounting, especially since public inquiries have as yet failed to hold anyone accountable.Footnote 53 Note, however, that public perceptions of the judiciary are not necessarily consistent with the concerns of lawyers.Footnote 54

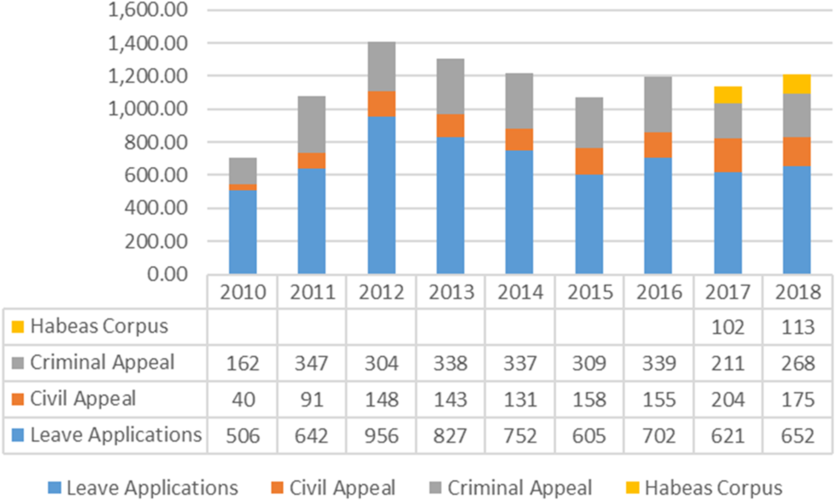

Over the last decade, the FC workload has been rising steadily, from 713 in 2010 to 1,208 in 2018. More than 50% of the cases are judicial review leave applications, followed by criminal and civil appeals (see Figure 1). Though still carrying forward a considerable number of cases each year, the court has managed to increase its disposal rate from 79% in 2012 to 116% in 2017—the result of a 10-year programme to reduce court backlogs and delays.Footnote 55

Figure 1. Federal Court case distribution, 2010–18. Source: Malaysian Judiciary Yearbook, 2010–18.

3. THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

The literature on judicial behaviour has identified numerous variables that enter into decision-making in supreme and constitutional courts.Footnote 56 Personal attributes and attitudes matter (e.g. policy preferences, personal attitudes to outcomes, and policies). Interaction within the bench also matters (natural pressure for consensus; concern for court reputation; a common desire to empower the court over competing political and judicial actors). Party politics may have some influence, such as in terms of loyalty to the appointer. Finally, these variables interact within specific constitutional and doctrinal contexts, some with more, others with less, legal formalism.

Which theory a scholar is following affects the relative importance of these variables. For instance, the legal model assumes that judges decide in conformity with laws and precedent.Footnote 57 It supports an image of judges as neutral and apolitical, using technical interpretation to ascertain the law that best applies to a given case.Footnote 58 Attitudinal theorists argue, however, that ideological positions and policy preferences shape judicial decisions, especially in courts of last resort.Footnote 59 They downplay the influence of the letter of the law and see judges as focused on legal policy. Footnote 60 The strategic model of judicial decision-making, also guided by the notion of judicial-policy preferences, acknowledges that judges take into account the views of other actors and the institutional context—and may even deviate from a preferred outcome to take those views into account.Footnote 61

A full discussion of these theories is beyond the scope of this paper.Footnote 62 Suffice it to say that models have increasingly incorporated ideas from each other and widened their scope, for instance when acknowledging that, as human beings, judges may pursue a host of goals beyond legal policy, such as personal standing with public and legal audiences,Footnote 63 career considerations, personal workload,Footnote 64 or maintaining collegial relations on the bench.Footnote 65 More recent academic debates have also increasingly raised concerns about how well certain models travel beyond the West.Footnote 66 Legal, attitudinal, and strategic accounts all tend to assume that political institutions and legal systems are solidly institutionalized, which is hardly the case in the Global South. They also tend to portray judges as insulated conflict adjudicators, motivated by individual preferences and engaging with other legal and political actors solely to advance their own goals. Yet the motivations for judicial behaviour are complex; often judges do not honour ideological fault lines, particularly in settings that are clientelist, weakly institutionalized, and highly relational.Footnote 67 There, the interplay between law and politics attracts more attention.Footnote 68

What we propose here is loosely inspired by the model identified in the literature as strategic.Footnote 69 Taking inspiration from earlier work on Asian jurisdictions by Garoupa and colleagues,Footnote 70 we first explore the context and then use the model to test some general perceptions of the behaviour of FC judges. We start with basic statistics on their backgrounds and the composition of the bench before testing specifically for the effects of the presidential administration, the work background of judges, and the generational cohort. We also control for age, gender, and decision trajectories over time. In other words, we do not assume that ideological preferences, which, in the Malaysian political context, are hard to discern, affect decisions for or against the government in high-profile cases; rather, we inquire into the possibility that the dynamics might be driven by personal traits like work background, appointments, and generational cohort—generally in line with the strategic model.

Taking into account widespread public views of the court, we test for four sub-hypotheses that relate to a strategic understanding of how FC justices behave:

H1 The pre- and post-1988 generations of justices behave quite differently. Justices appointed after the judicial crisis in 1988 are likely to be more deferential than earlier generations to the administration then in office and less likely to vote against it. This hypothesis tests for the widespread perception that 1998 saw a constitutional watershed moment that had detrimental effects on the courts.Footnote 71

H2 The closer justices are to retirement age, the more likely they are to vote against the administration, for reasons like those of the strategic model (e.g. rational calculations that executive backlash will have less impact as their tenure is ending). This hypothesis seeks to capture scholarly suggestions about strategic defection.Footnote 72

H3 Judges of non-Malay background (Indian, Chinese, indigenous, and foreign) are more likely than those of Malay background to vote against the government in high-profile cases, perhaps because they may be less aligned ideologically with the government or because of politicized appointments. This hypothesis is widely discussed in Malaysian legal circles, though not in the literature.Footnote 73

H4 Judges deciding cases under the prime minister who appointed them are more likely to vote for the government in high-profile cases than those appointed earlier. This hypothesis seeks to capture the loyalty and strategic alignment to the appointer that is widely acknowledged in the literatureFootnote 74 in terms of Asia’s presidential systems,Footnote 75 though Malaysia’s stable ruling coalition for over 60 years might imply alignment with any BN-led government rather than with individual prime ministers.

Our first step in testing is providing statistics to describe the FC bench over time. We then look more closely at the voting behaviour of individual justices, supported by inferential statistics on how certain traits may account for individual votes in the cases sampled.

4. DATA SET

We analyzed 102 decisions issued by the Supreme, later Federal, Court of Malaysia from 1960 through 2018 (Table A1 in the Appendix). We identified cases that were megapolitical based on (1) coverage on the front page of two major newspapers, (2) citations in articles about the FC in law publications, and (3) vetting by local experts. Our expectation was that, in megapolitical cases, personal and political factors would be particularly important to the decisions because of the nature of the issues and the weaker basis in legal doctrine for decisions in such matters.

The individual votes of each justice in the 102 cases constitute 385 observations. The outcome of interest—the dependent variable in the regression—is a vote against the contemporary administration. From the socio-biographic data on the judges in these cases, appointed between 1957 and 2018, we draw details for the 73 judges who voted on them, such as time on the bench, university affiliation, professional career and previous workplace, and ethnicity.

5. FINDINGS

Here, we begin by using descriptive statistics to demonstrate evolution of the bench over the sample period. We then analyze individual voting patterns across different dimensions, such as case types, terms of chief justices, and terms of prime ministers. We conclude this section by applying regression analyses to statistically test the several hypotheses.

5.1 The Bench

The sample period coincides with the administrations of PMs Tunku Abdul Rahman (1957–70), Abdul Razak Hussein (1970–76), Hussein Onn (1976–81), Mahathir Mohamed (1981–2003), Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (2003–09), Najib Abdul Razak (2009–18), and again Mahathir Mohamed (2018–present). During this period, 102 justices were appointed—the majority during Mahathir’s 22-year first prime ministership (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic profiles of FC justices, 1957–2018

Source: FC and public records.

The bench has been moderately diverse, though with obvious fault lines. For instance, no women were appointed until the 1990s, though the number has recently accelerated. Overseas legal education took place less at a university (Cambridge) than at one of the British Inns (Lincoln’s Inn, Middle Temple, Inner Temple) as part of specific classes for passing the Bar but, by 2018, all appointees were educated at the University of Malaya. In fact, the first law faculty of the University of Malaya were appointed only in 1972, though courses were previously offered in Singapore,Footnote 76 so that the early generation of Malay judges had little choice other than to go overseas; moreover, training at the Inns gave them access to the British Bar, which is still accepted as the equivalent of passing the Bar in Malaysia.

Meanwhile, ethnic diversity, which is closely tied to religious affiliation, has changed considerably; the share of Malay judges rose gradually from just 18% at independence to 66% in the 1970–90s and 76% in 1990–2009, peaking at 87.8% in 2010–17 before falling back to 71% with the 2018 appointees. Foreign judges were being phased out as early as 1952 and, by 1966, the bench was fully indigenized. Over the decades, the numbers of judges of Indian and Chinese background have varied considerably (Table 1).

During the sample period, with two exceptions,Footnote 77 FC appointees were consistently career judges, with the overwhelming majority since 1996 ascending from the Court of Appeal (94%) and the rest from the High Court (6%). As a result, most new justices, whose ages at appointment average 58, have already spent considerable time on the bench. The average tenure of an FC judge was 6.4 years. Except for three judges dismissed and three suspended during the 1988 crisis, most judges have retired as mandated at age 66.5 ((Table 2)—perhaps because an earlier departure would mean losing their pension benefits.

Table 2. Reasons for leaving the bench

note: At the time this paper was written, seven justices are active. Thus, the total number of justices who left the bench is 95.

Postgraduate degrees for FC judges are an exception (20%) and overseas training has been in decline. Until the 2000s, overseas training, particular in the UK, was the norm for most judges appointed to the FC who had studied law between 1960 and 1980. As training abroad gradually declined, the number of foreign-trained judges appointed to the FC bench declined to 43% in 2018—three of the seven justices had studied at the University of Malaya in the 1970s.

Since 2006, the diversity of the FC bench has been comparatively low, especially in comparison to the Court of Appeal and the two high courts. The gender ratio by contrast has been stable, perhaps as a result of closer JAC attention (Table 3).

Table 3. Federal Court vs. superior courts, 2006–18

Source: Judicial Appointments Commission website.

Our data reveal stable and very similar patterns for the Court of Appeal and the High Court, though the FC bench was more Malay-dominated in 2006–18. Considering the demographic distribution in Malaysia, the pattern is somewhat unusual.Footnote 78 It raises questions about appointments and career trajectories from the possible candidate pool to the FC bench (a task beyond this study, though the ethnic distribution of the 2018 FC appointees was a return to the general-historical pattern).Footnote 79 Moreover, unlike high courts in Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, in Malaysia, the path to the bench lies almost exclusively through a previous career as a judge and (except for the dismissals in 1988) the tenure of judges has been stable until retirement age.

5.2 Voting Patterns, 1960–2018

In general, the number of megapolitical cases rose gradually but steadily over time, though with surges in 1977, 1987, and 2015. The jumps respond closely to political challenges to the BN coalition: in 1977, as part of the declaration of the Kelantan Emergency in response to political violence; in 1987, the UMNO leadership challenge; and, in 2013, the BN loss of an absolute majority in Parliament. To some extent, the distribution of cases by category reflects this; more than a third dealt with civil liberties (37%), followed by executive prerogatives (19%), and religious content (12%); the rest related to separation of powers (12%) and elections (9%). Although 14 cases (14%) had at least one dissenter, decisions in the other 88 were unanimous (86%).

Of a total sample of 102 cases, the Supreme and Federal Courts decided 85% for and 15% against the sitting government. The court voted most often against the government in cases involving separation of powers (33%), executive prerogatives (32%), civil liberties (26%), and religious issues (one case of 12 brought) (Table 4).

Table 4. Case types, data set

note: Cases adjudicating economic and other issues are treated as Other.

Of these decisions, 76% were appeals, 10% original jurisdiction, and 14% referrals. The number of cases varied widely during the terms of the 14 Chief Justices covered; most were decided under Lord President Mohamed Suffian Bin Haji Mohamed Hashim (1974–82) and Chief Justice Arifin Bin Zakaria (2011–17) (Table 5).

Table 5. Case outcomes by Chief Justice, chronological order

note: Number of decisions is the total count of megapolitical case decisions made during the corresponding Chief Justice’s period of service. One exception is Justice James Beveridge Thomson, the first CJ in Malaysia, whose service began on 16 September 1963. Though the decision date of Case 1 (9 December 1960) and that of Case 2 (4 January 1962) were before his period of service, they are included in his term. Source: Data from the Malaysian Judiciary Yearbook 2018.

As for the percentages of anti-government votes—the number of anti-administration over total votes—there are three peaks: one in the first third of the sample period (1977), one in the second (1987), and one in the third (2003). Early in the study period, anti-government votes reached 40% but gradually dropped to about 20%, with small spikes in the 1980s during the first Mahathir tenure as prime minister (Table 6). Overall, as the 10-year moving average (the red line in Figure 2(a)) shows, anti-administration votes, though still differing by prime minister, have been declining gradually, perhaps because the executive has had greater control over the courts since 1988.

Table 6. Percentages of anti-government votes by prime minister, chronological order

note: Total votes is the sum of individual votes cast in megapolitical cases during a prime minister’s term. The percentages of anti-government votes is the ratio of anti-government to total individual votes.

Figure 2. Characteristics of voting behaviour at decision level. note: antigov_ratio (a) is calculated as the proportion of anti-administration total votes of the bench; dissent (b) takes a value of 1 if a decision involves at least one dissenting vote, 0 if unanimous. Horizontal variable year_of_decision is the year when the case was decided. The red line shows the 10-year moving average values over time. Note for years 1966 (2), 1969 (2), 1975 (3), 1976 (3), 1977 (6), 1979 (4), 1982 (3), 1985 (2), 1986 (3), 1987 (5), 1988 (5), 1989 (2), 1990 (3), 1992 (2), 1994 (2), 1999 (3), 2004 (3), 2006 (2), 2007 (3), 2008 (2), 2009 (3), 2011 (2), 2012 (2), 2013 (4), 2014 (4), 2015 (6), 2016 (2), 2017 (2), and 2018 (2), multiple decisions were issued (number of decisions are in parentheses).

Equally interesting is the fact that dissenting votes declined over the sample period and, except for 1987–88 and 2003–08, most decisions have been unanimous—and increasingly so toward the end of the sample period (Figure 2).

In short, as public discourse sometimes suggests, the FC has generally tended to vote for the government in high-profile cases, and few justices have dissented—particularly since 2014, which coincides with Najib Razak’s tenure as prime minister. There were, however, sharp differences in dissent and dispersion under CJs Zaki bin Tun Azmi (2008–11), Arifin bin Zakaria (2011–17), and to a lesser extent Mohamed (MD) Raus bin Sharif (2017–18). This may suggest that (1) the CJ has considerable influence on FC voting patterns, particularly as the bench has become increasingly homogenous; and (2) the CJ acts on behalf of the executive to deliver verdicts in favour of the government, as may have been the case since the electoral decline of BN in 2008.

5.3 Individual Voting and Regression Findings

But what about differences in the behaviour of individual justices? A close look at voting records reveals major differences in votes for and against the government. For instance, in our case sample, Justices MD Raus Bin Sharif, Abdul Hamid Bin Haji Omar, and Abdul Hamid Bin Embong voted for the administration more than 90% of the time and Richard Malanjum, Mohamed Salleh Bin Abas, and Lee Hun Hoe voted against more than 30% of the time (see Table A2 in the Appendix).

Similarly, though dissent has always been an exception, there are considerable differences in the willingness of justices to dissent from the majority opinion. In fact, in our sample of 73 voting judges, only 12 ever dissented (16%) and 61 never did (84%). However, George Edward Seah Kim Seng, Anuar Zainal Abidin, Ong Hock Sim, and Rahmah Hussain dissented in more than 30% of the cases they heard (Table A3 in the Appendix).

Such differences raise another question: do individual traits shape the voting patterns of FC justices? In other words, can we associate differences in voting behaviour to their personal characteristics? To find out, we engaged in some basic inferential statistics.

Our dependent variable (vote_against_government) is binary, with a value of 1 if the vote is against the administration, 0 if not. Of the independent variables, those related to judges’ characteristics are:

-

time_to_retirement: when the decision was handed down, how many years did a justice still have to serve before reaching mandatory retirement age? Though some justices did leave the bench before mandatory retirement age because they resigned or were dismissed or suspended (Table 2) and we knew when they would have retired, when the case was decided, their early departure was not predictable

-

appointed_after1988: a dummy variable, which proxies a possible structural change that might have emerged after the 1988 assault on the court

-

muslim: a dummy variable indicating the religious background of the justice

-

chinese, indian, british_colonial, and indigenous: dummy variables representing ethnic background. There is no dummy variable for Malay because that is the ethnicity reference category. British judges whose tenure carried over from the colonial period are classified as british_colonial

-

female: a dummy variable that captures the difference in voting behaviour by gender

-

appointer: a dummy variable that captures the effect of loyalty to the appointing prime minister

-

overseas_trained: a dummy variable that proxies whether the voting behaviours of overseas-trained and domestic-trained justices differ.

In addition to the justices’ characteristics, we collected case characteristics and chose corresponding dummy variables:

-

plaintiff: a dummy variable that indicates whether the plaintiff is the government

-

original and referral: dummy variables for type of jurisdiction. Since most cases were appeals, that is the reference category

-

case type dummy variables: a set of dummy variables representing the case types in Table 4. Civil liberties is the reference category

-

chief justice dummy variables: a set of dummies CJ periods of service. Each takes 1 if a vote was decided during the specified CJ’s term, 0 otherwise. See Table 5 for their exact tenureFootnote 80

-

prime minister dummy variables: a set of variables similar to those for CJs. See Table 6 for their exact terms of office.

Table A4 in the Appendix summarizes the descriptive statistics for individual variables.

In the 384 votes by the 73 justices in 102 cases from 1960 to 2018, the data distribution is far from balanced; the number of votes of individual justices ranged from 1 to 20, and the average was 5.27, the median 4, and the mode 4.Footnote 81 We therefore fitted a pooled-cross-section Probit model and estimated the parameters by maximum likelihood (Table 7). To account for the possible lack of independence among individuals voting on a case, observations were clustered by cases, and the cluster robust standard errors of the estimated parameters calculatedFootnote 82 using STATA 15. Since this is a Probit model, instead of reporting the estimated coefficients, Tables 7 and 8 summarize the marginal effects. Models in Table 7 use the Muslim dummy variable, which is replaced in Table 8 by the ethnic dummy variables.

Table 7. Probit regressions with individual religion dummy variable, explaining against-vote, reporting marginal effects

note: STATA 15 is used for estimation. Since individual votes within decisions are likely to be dependent, cluster robust standard errors of the coefficient estimates are calculated and reported in parentheses under the estimated marginal effects. The number of asterisks ***/**/* indicates statistical significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%. Count R 2 is a goodness-of-fit measure, which is the proportion of correctly classified predictions, by setting the threshold at commonly used 0.5. Though specifications (4)–(6) include additional dummies, estimates are not reported for brevity.

Table 8. Probit regressions with individual ethnicity dummy variables, explaining against-vote, reporting marginal effects

note: STATA 15 is used for estimation. Since individual votes within decisions are likely to be dependent, cluster robust standard errors of the coefficient estimates are calculated and reported in parentheses under the estimated marginal effects. The number of asterisks ***/**/* indicates statistical significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%. Count R 2 is a goodness-of-fit measure, which is the proportion of correctly classified predictions, by setting the threshold at commonly used 0.5. Though specifications (4)–(6) include additional dummies, estimates are not reported for brevity.

In seeking an appropriate model for testing the hypothesis, we realized that, since the number of observations differs depending on the model, a direct goodness-of-fit comparison is not feasible. The lower panel of Table 7 reports multiple pseudo-R 2s.Footnote 83 Footnote – Footnote 85 In terms of McFadden’s R 2 and Adjusted Count R 2, Models (4) and (6) seem to be most appropriate. Since both include CJ and PM dummies, their redundancy was also tested. Chi-squared statistics indicate that both CJ and PM dummies can be excluded in Model (6), but CJ dummies should not be excluded in Model (4). Therefore, Model (4) is our selected baseline model.

We next test the hypothesis based on Model (4), as follows.

-

1. The marginal effect of the appointed_after1988 dummy is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, which indicates that justices appointed after 1988 are more likely to cast a pro-government vote. This supports our hypothesis that the behaviour of justices changed after 1988: in H1, we hypothesized that justices appointed after the 1988 crisis were likely to be more deferential to the administration. The estimated marginal effect suggests that anti-government votes of the post-1988 generation are lower by 25.7%. The robustness of this finding is supported by the fact that similarly negative, and slightly larger, effects (27.8% less than Model 4) are observed in Model (6). However, being careful, we assume that the nature of the cases is the same throughout the sample period. Thus, if cases heard after 1988 are more favourable to government, there is a possibility that the dummy variable captures this effect.

-

2. The coefficient of time_to_retirement in Model (4) has a positive though insignificant coefficient rather than what H2 would predict. The results might suggest that the longer the time to retirement, the higher the probability of voting against the sitting government. However, comparison of the coefficients in Table 7 reveals that this variable is unstable and mostly insignificant. Thus, we conclude that strategic defection closer to retirement does not apply to Malaysian SC/FC justices; perhaps loyal judges in Malaysia’s semi-authoritarian regime have been offered post-retirement positions, which might influence their strategic calculations.

-

3. The marginal effects of the muslim dummy variable in Table 7 are all negative and significant, which confirms H3: a Muslim justice is more likely to vote for the government than a non-Muslim justice. According to the estimates for Model (4), the predicted probability of a pro-vote increases by 12.6% and is statistically significant at the 5% level. To examine this from a different angle, we replaced the variable muslim with four ethnic dummy variables (the reference category of ethnicity is Malay). Table 8 summarizes the results. In Models (4) and (6), the coefficients of chinese, indian, and indigenous are all positive, and for chinese and indian are mostly significant, which supports H3. The estimated marginal effect of a justice being of Chinese background is 13.2% (Model (4)), which is almost comparable to the marginal effect of muslim for a justice. The effect is even higher for Indian justices (27.2%). For a justice with indigenous background, coefficients are positive but, possibly because the number of observations is small (nine votes), they are all insignificant.

Lastly, the british_colonial estimate should be interpreted with caution, since these justices heard only two cases early in SC/FC history, and the number of votes is just four. Overall, for the majority of ethnicities, the coefficients are positive and, in the Chinese and Indian groups, statistically significant. These results strongly support H3.

-

4. In Tables 7 and 8, the marginal effect of appointer is estimated to be about –9%, with statistical significance at 5%. The results therefore strongly support H4.

There are several other interesting findings: female justices, for instance, may tend to vote against the government—all estimates have positive signs—but the effect is not statistically significant. With respect to appeal jurisdiction, the probability of anti-government votes in the original jurisdiction will be about 20% lower, and the effects are statistically significant for some models. However, the probability of referral jurisdiction is statistically indifferent from that of appeal jurisdiction. Concerning case type, Models (4)–(6) in Tables 7 and 8 do not reject an exclusion restriction of corresponding coefficients by Chi-square tests, which indicates that there is no statistically significant difference between case types.Footnote 86 Lastly, none of the marginal effects of overseas_trained was statistically significant.

6. CONCLUSION

The Federal Court of Malaysia offers a fascinating, though complex, opportunity to study judicial behaviour. Since Malaysia’s independence in 1957, the FC has benefitted from continuous institutionalization and professionalization, which has not only allowed it to escape the fate of many of its short-lived counterparts in the region, but also explains why it has emerged, like the courts in general, as one of the most respected Malaysian institutions. And yet, as might be expected from an institution that has generally operated within a coalition-controlled, semi-authoritarian environment, it has also struggled to insulate itself against executive interference. As a result, it has regularly been accused of bias in high-profile cases and of declining professionalism—problems that seem to have burgeoned since the constitutional crisis in 1988.

Taking these widespread public and academic concerns as a starting point, this paper offers one of the first empirical accounts of the behaviour of FC justices in high-profile political cases. Such cases are particularly suitable for this type of investigation because, their legal basis often being unclear, it is reasonable to assume that strategic behaviour and attitudinal positions come into play as they are being decided. Our findings, we hope, while not a replacement for legal-interpretivist scholarship, offer a much-needed empirically grounded, and more nuanced, perspective on the FC’s six-decade track record.

Our carefully selected sample offers much support for some common claims. For instance, while certainly Malaysian judges have traditionally exhibited a pattern of legal formalism, reinforced by the common-law system, which has made the FC less activist and engaged in high-profile cases than some peers in the region, over time, megapolitical FC cases have gradually increased, with surges in 1977, 1988, and 2013. Meanwhile, both votes against government and dissents by FC justices from their peers on the bench have been declining.

While not all our hypotheses could be confirmed, we provide statistical evidence for three key findings, as shown in Models (4) and (6). First, the paper very clearly validates H3: judges from a non-Malay background are more likely than Malay judges to vote against the government. Second, as postulated in H1, judges appointed after the 1988 constitutional crisis are more likely to vote for the government than those appointed before 1988. Third, judges appointed by the current prime minister are also more likely to vote for his government (H4), though it is not entirely clear whether this effect captures loyalty to an individual prime minister or simple loyalty to the BN ruling coalition after six decades of single-party dominance.

There is much room to speculate why these patterns occur. For instance, despite its traditional hesitance to get involved in high-profile political cases, the court has become less able to evade them. This is partly because Malaysia’s multi-ethnic society has over time become more contentious and partly because the political regime itself has often found it useful to delegate to the court those complex questions of religious freedom and sedition and to adapt the courts for its own political purposes, as in the Anwar cases. In fact, with the FC operating within a semi-authoritarian system for most of its existence, it may above all be that the stability of the BN coalition, in allowing the executive to pressure the courts, may have most influenced executive-judicial relations, and thus the types of cases heard and ultimately the decisions to be expected. In other words, moments of regime weakness and elite infighting (e.g. 1987, 2008, 2013) and the ability of the executive (e.g. PMs Mahathir I and Najib Razak) to respond by tightening control of the court are often crucial to the pattern of judicial engagement in megapolitics in this less-than-democratic environment.

This is not to imply that judges have no agency: as shown in the run-up to the 1988 judicial crisis, after appeals to the Privy Council ended, the efforts of then-Lord President Salleh Abas to chart a new path for the courts in effect set judges and the FC on a collision course with then-PM Mahathir as he was battling for his own survival. Similarly, the brief willingness of Malaysian appellate courts after BN lost its absolute parliamentary majority in 2008 to articulate a more generous interpretation of rights, check legislative and executive actions, and strike down provisions that infringed fundamental liberties might constitute strategic moves to seize on long-held ambitions for “constitutional redemption.”Footnote 87 Yet these sometimes uneven initiatives were short-lived,Footnote 88 particularly in the FC, after PM Najib Razak was again able to tighten political control.

Our study, and anecdotal evidence, suggests that both appointments to the bench and the role of the Chief Justice deserve more attention as possible explanations for what is happening in the FC. For instance, the FC bench became far less diverse in terms of ethnicity and religion, in fact became Malay-dominated, after 2013 when BN began to face heavier electoral competition and the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal was growing. Although, in the FC, Malay judges do not consistently vote as a bloc, they certainly do so more often than non-Malay judges.

Also to be considered are recent allegations of politicized promotions to the FC that ignore long-standing traditions of seniority; pressure allegedly exerted during this period, sometimes by the CJ himself, on judges in high-profile casesFootnote 89 ; and efforts by political actors after the 2018 election to unconstitutionally extend beyond retirement the terms of the CJs of both the FC and the Court of Appeal. The question is then whether such indicators of executive influence might explain the voting patterns identified. The sudden return to a more average ethnic distribution for the FC under the current Mahathir government only reinforces that view.

Recent political change after almost 60 years of BN dominance might offer room for cautious optimism. The appointments of Chief Justices Richard Malanjum (2018–19), known for an independent streak as an FC justice in high-profile cases brought by the PH coalition, followed by the elevation of the highly regarded Justice Tengku Maimun binti Tuan Mat (2019–) as Malaysia’s first female CJ, won vigorous applause from the Malaysian Bar.Footnote 90 Reforms are also underway to assess and streamline the work of the courts and reform the current appointments process, carefully watched by Malaysia’s outspoken lawyers.Footnote 91 And, while the reformist PH government (2018–20) had been criticized for moving too slowly to act on its election promise to strengthen the courts and the rule of law,Footnote 92 there has nevertheless been a noticeable sense of optimism in the air, and an obvious desire among both judicial and political actors to rectify the continuing fall-out from the 1988 events. The appointment of three women to the FC bench in 2019—bringing the total to a peak of six women judges in 2020—also supports cautious optimism, though it will be interesting to see whether the new political coalition formed in 2020 will continue the reform momentum.

Professional, independent, and impartial judges are always preferable. Malaysia’s political system has become more competitive, and its multi-ethnic and secular-religious constitutional foundation, with tensions between religious and liberal constitutional rights, is likely to be further challenged in coming years.Footnote 93 Whether and how Malaysia’s FC will be able to live up to these expectations—to revive the vision expressed by former Lord President Tun Mohamad Suffian quoted at the beginning of the paper—will depend on a host of factors, some of which this study has tested for. It is our hope that the study can help provide a useful evidential foundation for continuing thorough the evaluation of one of Malaysia’s most critical institutions.

APPENDIX

Table A1. Case list

Table A2. Top six voters for and against the sitting administration, 1960–2018

note: This includes only those judges with nine or more total votes in the data set. Among the against-voters, the second and the third ranks, and the fifth and the sixth are tied.

Table A3. Top six dissenting judges, 1960–2018

note: A dissenting vote is a vote by one or more justices expressing disagreement with the majority. The dissent ratio of a justice is the proportion of total dissenting in total votes.

Table A4. Descriptive statistics of variables