1. INTRODUCTION

Legal professionals act upon their ideas. Both the barFootnote 1 and the benchFootnote 2 are driven by their ideas of law, rights, and politics. There is limited discussion, however, of where they get their ideas from. In the North American context, professional socializationFootnote 3 tracing lawyers from school to firms provides an explanation as to why and how lawyers choose their practice and career, while the lawyer–client relationship offers a strong framework for understanding the origins and variances of cause lawyering.Footnote 4 In contrast, neo-Weberian scholars of the legal profession portray lawyers as self-interested actors seeking market control and social closure.Footnote 5 These schools of thought nicely point to the social and economic origins of professional identity, yet it remains unclear as to where, and how exactly, the legal profession conceives the identity to inform their political actions.

In the Asian context, politics is not an unattended topic in the study of lawyers. Lawyers are statesman politicians in both democraticFootnote 6 and semi-democratic regimes,Footnote 7 mobilizers in both economically developingFootnote 8 and developed societies,Footnote 9 and often carry out normative pursuits, most notably human rights and the rule of law, in courts and on the streetFootnote 10 to challenge political power despite continuous and often harsh suppression.Footnote 11 Much of the literature in the field of Asian law and society, nevertheless, is reluctant to explain the political source of professional identity,Footnote 12 and often neglects the variation in normative ideals that the legal profession embodies. In practice and quite frequently, legal professions in one jurisdiction show divergent political orientations. In Japan, for instance, the judiciary has a consistently conservative tendencyFootnote 13 but the lawyers “aggressively promoted the idea of autonomous law and the liberal state.”Footnote 14 Arguably, the legal profession is not one actor, but multiple ones.

Regarding the intra-professional variations, especially in the Asian context where state, market, and civil society often share an entangled relationship, the legal profession is inevitably part of the dynamic evolution, leading to its heterogeneous nature. As Dezalay and Garth identified in their study of Asian lawyers: “[legal] elites … are not homogeneous or united by any particular approach to state governance.”Footnote 15 Indeed, scholars who study liberal pursuits of the legal profession have long argued that lawyers alone cannot accurately represent the overall political activities and a collectivity of the “legal complex,”Footnote 16 including judges, academics, and other legal actors, should be the analytical focus. However, the literature on the legal complex made a great contribution in specifying a set of actors and a set of liberal values that drives their actions, many of which are political in nature, yet remains unclear on the ideational pattern. That is, who gets what norm, from where?

What, then, explains the political origins of professional identity in the legal sector? And how can we explain the intra-professional variations? To answer these questions, I focus on the politically active legal professionals. In this paper, I argue that legal professionals critically develop their core identity in collective action, or resistance, in relation to the incumbent rule when the state undergoes fundamental power reconfiguration. That is, it is their political position as opposed to power in a critical juncture of state transformation that determines the legal profession’s collective ideal of who they are and what actions they take. Intra-professional variations emerge in accordance with the differentiated political positions they take during this time period. Specifically, this paper uses the three Taiwanese legal professions as a case-study to demonstrate how democratization shapes professional identity: as lawyers, judges, and prosecutors experienced different levels and models of authoritarian containment prior to and during state transformation, they took separate trajectories of political resistance to the incumbent rule, which explains why the three legal professions pledge to different normative commitments, leading to different professional identities. While Taiwanese judges categorically defend collective independence, lawyers assertively advocate for people’s rights, and prosecutors marshal under the banner of justice.

Undoubtedly, not all legal professionals are politically active. In fact, the majority of them are routine practitioners indifferent to affairs beyond their daily practices and circles. To study the political origins of professional identity, hence, is not to claim that the legal profession is a homogeneous political species and that only one, singular political orientation dictates their thinking. Rather, I aim to present three strong ideational traditions, empirically co-existent with a reoccurring pattern of evolution in the three major legal professions in Taiwan, that anchor prominent debates in the legal sectors that even those who are indifferent and in opposition would need to acknowledge and reckon with.

To capture the ideational baseline and differentiated priorities of these legal professions, this paper relies on empirical data from a seven-month fieldwork study in Taiwan between September 2016 and March 2017, and three returning trips in summer 2017, winter 2017, and summer 2018. I conducted: (1) 133 interviews with 164 legal practitioners, including 35 judges, 14 prosecutors, and 103 lawyers, in addition to legislators, academics, policy officials, and non-governmental organization (NGO) staff; and (2) archival research, including news articles, statements, periodical publication, memoir, meeting minutes, policy memos, and other unpublished documentation provided by interviewees. I also conducted participatory observation and online ethnography, recording my experience and conversations with various types of legal professionals of different seniority and capacity in public or private settings. While not all legal practitioners I interacted with engaged in collective actions of any sort, observations from those who were politically inactive also provide crucial evidence as to how certain legal practitioners’ actions and words are perceived and constructed in the community. With in-depth field immersion, I was able to capture the legal professions’ evolving identity from not only macro-historical events, but also their micro narratives and communal, collective memories.

The paper first theorizes the pattern of ideal embodiment, with a brief overview of the three Taiwanese legal professions. The following section, using historical documentation and interviews, presents the emergence and reinforcement of a respective professional identity for lawyers, judges, and prosecutors in Taiwan. I use three detailed subsections to delineate the political containment the professions experienced, focusing on their actions in the 1990s as well as the rationale behind them. I also follow their professional development into the twenty-first century to trace the consolidation of different professional norms. A note of theoretical contributions, with a comparative discussion of other Asian contexts, concludes the paper.

2. THE PATTERN OF IDEAL EMBODIMENT

For those politically active legal practitioners, professional identity is forged from the legal profession’s political positions in relation to the incumbent rule during fundamental state power reconfiguration.Footnote 17 This critical juncture is the formative stage, for two reasons. First, it marks a period of disorientation in which ideals become imperative to define preferences. Actions at the time of disorientation provide authoritative diagnoses as to what the current legal system is, and an interpretive frame as to what a good legal system should be. Second, it is also a period when different fractions of the legal profession take on diversified fights with the power regime to channel diffusive and unaccountable political power into rules and legal institutions. The state contains the legal profession with varying approaches, depending on the nature of the political regime and the institutional design of the profession. While political resistance, or collective action, takes place in differentiated institutional arenas, legal professionals direct their attention to different norms and construct self-expectations. That is, depending on the prior relationship with the incumbent power, different divisions of the legal profession focus on different ideals of what a legal system should be, resulting in different commitments as to how a legal professional should act.

A professional identity is an ideal image that a legal professional aspires to. Such professional ideals, namely prioritized norms and normative role-settings, are reinforced by various social mechanismsFootnote 18: (1) formation of “reformist” networks; (2) recognition, indicated by movement towards authoritative positions (or creation thereof), including governmental posts, professional agencies, or other societal leadership; (3) transmission and/or elevation of selected norms and ideals, including expansion within the profession and endowment to the younger generation, sometimes through formal educational institutions. These three mechanisms are not logically or empirically sequential; rather, they take place in a reinforcing manner and variations of composition exist in different legal professions’ development.

The first mechanism of ideal embodiment is the formation of a “reformist” network. Professional identity, analytically treated as an exogenous component to hold explanatory power, is notoriously difficult to observe empirically. Methodologically, however, carriers of ideas can be identified and recorded. Constructing a collective ideal of a profession can, therefore, empirically equate to an assembly and association of like-minded professionals, who claim to be a collectivity, and are seen as a collectivity. In addition to the voluntary statement, deviation in action or discourse from established groups or practice in the profession also demonstrates strong evidence of the formation of new ideas. While legal professionals are often embedded in politics during power reconfiguration, their unconventional actions deviating from the original political arrangement, be it a challenge or an alternative, in institutionalized or extra-judicial arenas, are often labelled “reformist,” which constitute a clear indication that new ideals are being conceived.

The second mechanism—movement towards authoritative positions, or the creation thereof—marks a critical stage of ideational transmission: recognition. Following the actors who carry reformist ideals, movement towards authoritative positions indicates not only the dissemination of ideas, but also their acceptance by the professional constituency. For example, election to leadership in professional associations or agencies is direct evidence of endorsement from the general membership or, to say the least, a critical majority of the membership. Appointment to governmental posts indicates official acknowledgement of the previously unconventional ideals and implies support to institutionalize the new ideals. Similarly, the creation of authoritative positions, such as an outspoken NGO, suggests material resources (be it personnel or monetary) to realize or advocate for new ideals. All these are crucial processes of ideational embodiment.

The expansion and/or elevation of selected norms and ideals is the third essential mechanism. While the previous mechanism, recognition, denotes a critical moment of validation, before or after the moment, there must be a complementary process of ideational expansion and elevation. Empirically, three features indicate this advancement: numerically, more fields adopt the rhetorical framework of the newly established professional norm, or simply more discussions about the specific professional norm present themselves after the reformist network is formed and begins to advocate. Following these idea carriers, emergence of succeeding generations in the reformist network indicates intellectual ancestry, which is the second empirical feature of ideal transmission. Third, transmission can be observed by comparison: some proposed norms fail to be institutionalized, while other norms do succeed, such as in shaping policy initiatives. That is, examining the variations of ideational developments allows us to verify the embodiment of ideas by distinguishing the successful ones from others.

To examine the political origins of professional identity, the three Taiwanese legal professions are an exemplary case: lawyers represent peoples’ rights, judges defend independence, and prosecutors pursue justice. Their selection of ideal was determined first by their respective relationship with the authoritarian Kuomintang (KMT) regime during democratization and later evolved to establish external legitimacy and strengthen internal collective norms. Evidently, the pattern of ideal formation and consolidation in the three legal professions is consistent: a small group of young, liberal, and similarly minded practitioners formed a close network, gained public exposure in one specific collective action against the party-state scheme with identifiable support from their own professional group, and then they moved to positions of authority, even creating positions of authority to acquire resources and sustain the pursuit of their ideal.

3. INTRA-PROFESSIONAL IDEALS: JUSTICE, JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE, AND THE PEOPLE’S RIGHTS

The three Taiwanese legal professions pledge to different professional norms in accordance with their political positions and experiences with the party-state. The timing of ideational transformation also reflects this political relationship: Taiwanese lawyers, incorporating most social momentum afar from direct party-state manipulation, made a major breakthrough early in 1989–90; judges, with a strong constitutional mandate and political concession, started a series of norm-building in the mid-1990s; and prosecutors, facing the most persistent (attempts at) political control, aligned the latest, in 1998.

Taiwanese lawyers experienced a modest degree of control, as the state contained the bar from upstream by a differentiated admission policy. As the following section shows, the government mainly admits legal practitioners with a prior relationship to the state to ensure their deference before entering the profession, yet has limited direct control of the overall lawyer population. Being a relatively autonomous and embedded actor in the Taiwanese society, liberal-minded lawyers first reclaimed their own bar association and quickly joined the societal momentum at the height of democratization to become the Taiwanese people’s advocate. Taiwanese judges, on the other hand, were systematically restrained through multiple channels to institutionalize their conformity, which, in turn, allows political influence to trickle down. Pushing back against this party-state manipulation, judicial independence became the highest priority and focus for action. Co-optation serves the main strategy of judges during democratic transition: skilfully utilizing various institutional platforms available to them, reformist judges collaborated with politicians and judicial bureaucrats to consolidate the normative pledge, despite the fact some of them were agents of the authoritarian party-state. Prosecutors, however, witnessed the strongest degree of political control. Institutionally inseparable from the state, prosecutors faced top-down and persistent attempts to instrumentalize them, even after Taiwan’s first party turnover in 2000. Combating such abuse of power, Taiwanese prosecutors developed an identity of justice. The reformist prosecutors consistently resist policy or political actions aiming to compromise them; they focus on investigating corruption and only selectively co-operate with the administration to secure conditions facilitating such pursuit of their ideals.

3.1 Lawyer: Advocating for People’s Rights

In Taiwan, a strong tradition of “people’s advocate”Footnote 19 is shared by many politically active lawyers. Originally initiated in the 1990s, the identity as “the legal profession in opposition (在野法曹, Zaiye Fazao)” denotes the mission that lawyers should scrutinize those in power and advocate for those who are not. This professional norm was developed as opposed to the KMT party-state by a minority of locally educated lawyers in the 1980s. Most evidently observed in their contestation in the Taipei Bar leadership elections, the final success in 1990 marked the end of not only state control over their profession, but also the baseline principle representative of Taiwanese lawyers’ collective pursuit.

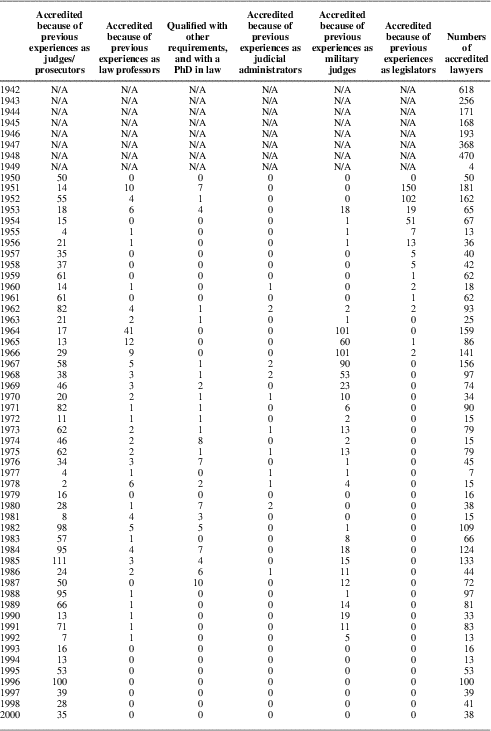

For decades in the twentieth century, Taiwanese lawyers were contained by the authoritarian state through the filtered admission to the bar. After the end of the Japanese colonial rule in the mid-1940s, the KMT government adopted two parallel schemes to qualify lawyers in Taiwan: the accreditation system and the bar exam. To man the legal sector while limiting its autonomy, the government accredited a large number of military judges, military prosecutors, former court personnel, and experienced civil servants to become lawyers (Table 1).Footnote 20 By contrast, bar-sitting lawyers who were usually college law graduates without prior connection with the state constituted a minority until 1987 (see Figure 1 and Table 2).

Table 1 Intra-professional ideals and differentiated models

Figure 1 Bar-sitting lawyers vs. accredited lawyers in Taiwan, 1945–2000.

Table 2 Number of accredited lawyers by category, 1942–2000

The original data source is the Ministry of Examination in Taiwan. This table was compiled by Chang (Reference Chang2007), pp. 51–3, and translated by the author. Data before 1998 were compiled by Heng-wen Liu (Reference Liu2005), pp. 241–2.

The “military lawyers” admitted via the accredited system not only took up a substantial proportion of the bar, but also leadership positions at the bar, financially and institutionally supported by the KMT.Footnote 21 A small number of bar-sitting lawyers, self-identified as “civilian school lawyers (文學校律師),” started to contest the pro-KMT board at the Taipei Bar in the 1970s, but they were only able to take up a margin. Even with a key mobilization in 1979, ignited by the Formosan Incident, a major crackdown against democratic uprising,Footnote 22 civilian lawyers remained a minority in the bar. In the late 1980s, another generation of civilian lawyers “grew positive about the chance to win”Footnote 23 as the national bar exam opened up a demographic base to support their cause to challenge the party-state control. This group of young lawyers, mostly in their thirties at the time, reached out horizontally through their alumni network and actively sought leadership from established lawyers to connect vertically with previous generations.Footnote 24 An esteemed patent lawyer, Lin Ming-sheng, was persuaded by the young lawyers to lead the Alliance of Civilian-School Lawyers (ACL) (文學校律師聯合團) after he witnessed the bottom-up momentum in the community, with an organized outreach survey and “a well-attended banquet at the Grand Hotel” (TW201738). Lin Ming-sheng and the ACL won a landslide victory in 1990, where they took all seats on the board of directors and advisers at the Taipei Bar. The campaign successfully mobilized many silent members, long expecting a local leadership to contest the party-state lineage of the bar, as a senior partner in one of the top corporate law firms remembered: “Some old lawyers rented hotel rooms right across the street from the voting venue, so they can get to the voting booth first thing in the morning” (TW201738).

The ideational shift was apparent after the civilian lawyers took over the Taipei Bar. The slogan of the new team was “talk and walk” and literally “voice concerns about external issues and serve the members in the community.”Footnote 25 It initiated a wide range of projects promoting rights protection and the moderation of state power, including advocating for constitutional and judicial reform, naming corrupt judges, revision and abolishment of special criminal laws, legislation prohibiting gendered violence, innocence rescue, and a number of public statements supporting freedom of speech as well as democratic participation in general. This shift of political role, challenging power as a professional body, was in fact disapproved of by some members, who reported to the High Prosecutors’ Office that “Lin Ming-sheng and all 41 board members of the Taipei Bar … are suspected of rebellion.” The prosecutors’ office opened a case but did not prosecute as “political statements about constitutional reform are yet to be deemed as intention to usurp.”Footnote 26 The challenge from within the community nicely demonstrates that the ACL emerged as a contender that disturbed conventional political practices in the profession, yet norms that the ACL stood by were reaffirmed by the incidents challenging them.

Despite challenges from within and massive changes in the market and the political climate in the following decades, this network of liberal lawyers has successfully maintained their influence and legitimacy. As a closely connected network, the ACL network effectively sustains its line of succession, as a former administrator in the network explained (TW201715):

ACL is like a gang, the old boys decide things. Principally this is how ACL works: in a three-year term at the Taipei Bar, there would be two people serving directorship, each takes up one and a half year in that term. Then one of them would become the director at the national level, at the Taiwan Bar Association. Only one person because the Taipei Bar has to share the three-year term there with lawyers from mid- and south-Taiwan.Footnote 27 So every three years you get a “class” of old boys. After they graduate from their directorship, they become old boys and enter the “senate.” Plus other old boys from previous years, they will discuss which candidates are to be directors in the future.

The domination has lasted for over 25 years to date. Although the current bar leaders chose to run under a different banner, the “United Campaign Team,” in the 2017 Taipei Bar board election, the network lineage and intellectual ancestry were openly known (TW201634; TW201702). In the 2017 election, the network faced disputes to challenge their long-lasting influence that the ACL network had become a generational monopoly (TW201602; online ethnography April 2017; also implied by two senior lawyers in a group interview TW201737). Yet the ACL network has consciously recruited young opinion leaders, typically those in their mid-30s, and nominated them to the board: “opposition is welcome! We all challenged them [seniors] when young” (From a Taipei Bar Association board member, TW201737).

The dissemination of the reformist ideal that lawyers should advocate for the people goes beyond bar associations. Catching the wave of democratization, many who carried reformist ideals entered, even created, diverse types of leadership positions in the rapidly transforming Taiwanese society. On the one hand, a number of active members of the Taipei Bar entered politics to run the newly democratized government.Footnote 28 In the 1990s, the electoral system began to open up, and lawyers associated with the ACL network logically transferred their expertise as advocates and their identity as local elites into representative politics. In the civil society, on the other hand, the liberal lawyers connected to a wide range of civic movements as they shared the same momentum challenging the party-state. Directly funded and lobbied by the ACL network, the Judicial Reform Foundation (JRF) was established in 1995 as a NGO,Footnote 29 while the Legal Aid FoundationFootnote 30 was legislated for in 2003, fully funded by the national budget but run by an executive team of lawyers. Despite three party turnovers in the twenty-first century, both organizations expanded exponentially in budget scale and stood as key players shaping the agenda of judicial policy and practice of access to justice in Taiwan.Footnote 31 Loosely connected to the network are the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, the Humanistic Education Foundation, the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty, and a feminist lawyer Yu Mei-nu, who successfully led gender-equality movements in both constitutional litigations and legislative lobbying by the mid-2000s.Footnote 32 Admittedly, the ACL and the related networks do not represent all causes of all Taiwanese lawyers.Footnote 33 There are a number of key organizations supported by lawyers (such as the Consumers Foundation) and other lines of legal mobilization (such as the environmentalist attorneys connected to the Wild at Heart Legal Defence Association) contributing to the vibrant and diversified “rights revolution” in Taiwan. Nevertheless, the ideal that the ACL signifies—lawyers as “the legal profession in opposition”—is still representative of Taiwanese lawyers that marked the beginning of such ideational turn.

Simply put, the impact of such an ideal is twofold. First, the embodiment in the early 1990s directly and radically changed the character and self-perception of the profession, from a contained subordinate of the party-state apparatus to an autonomous and vocal representative of Taiwanese citizens. Those who carry these ideals sustained their influence in the profession and mobilized societal and political capital to institutionalize and expand this line of pursuit. Second, the rhetorical and symbolic legitimacy of “people’s advocate” has been elevated to become the default in the community, which in turn prepares a space to facilitate other lines of advocacy. After all, a functional democracy allows a wide variety of causes, and it is only natural for this professional ideal in the name of the people to be so prevalent that it is hardly discernible from the general public-interest practice of lawyers as Taiwan democratizes.

3.2 Judge: Defending Independence

Taiwanese judges, by contrast, strive for independence. The Taiwanese experience nicely demonstrates that judges act to defend judicial independence not out of pure self-interest or strategic concern,Footnote 34 but for normative reasons. That is, judges act because they believe they should be independent, as opposed to the institutionalized control they witnessed in the party-state era. Similarly to the pattern of formation and dissemination of their lawyer counterparts, small groups of young and reformist-minded judges first aligned in the early 1990s, and collectively mobilized to challenge the top-down administrative control and lobbied for constitutional protection of judicial independence. The network later entered management positions in the judicial bureaucracy, first under KMT, and continued working with the administration after the first party turnover in 2000.

The party-state control over the Taiwanese judiciary, suggested by emerging scholarship, came through multiple channels.Footnote 35 First, the KMT officially set up party offices in the judiciary in the 1950s and encouraged judges and prosecutors to join the party until the early 1990s. In 2011, when the Judge Act was signed into effect and required residing judges to terminate political party affiliation, roughly one-quarter of the whole judiciary made statements giving up party membership (see Table 3). Although no historical documentation is available to track the KMT’s recruitment activity annually, the fact that a higher proportion of senior judges in upper courts held party membership suggests a systematic penetration of KMT operation in the authoritarian era, as the KMT was the only lawful political party before the party ban was lifted in 1987 and, effectively, judges had exclusive exposure to it.Footnote 36

Table 3 Judges invalidating political party membership

This table was extracted and translated from Tsai (Reference Tsai2013), p. 41. Tsai, currently a Constitutional Court justice and the vice-president of the Judiciary Yuan, has been a key figure in many reform initiatives and a relatively open-minded judge, holding administrative posts in the past decades. This table is based on his access to official statistics. I thank Heng-wen Liu for bringing this piece of data to my attention.

Second, the selection process and professionalization strengthened obedience to authority and seniority.Footnote 37 That is, in both the examination and training stages, apprentice judges were instructed to follow a standardized format of writing and thinking to produce consistent judicial decisions that did not deviate from the judicial hierarchy. Decisions made by higher courts were to be followed but not challenged, and innovative reasoning was deemed inappropriate. In addition, similarly to the military, Taiwanese judges always identified each other by seniority, according to the year of graduation from the Academy of Judiciary. Relatedly, a third mechanism was hands-on administrative supervision in everyday practice; the most notable mechanisms were non-transparent case allocation and promotion control.Footnote 38 In fact, these institutional control devices were the first targets to reform.

The top-down, multi-channel, and institutionalized political containment started to crack because of a bottom-up challenge from within the judiciary. In 1993, a group of young “reformist judges,” who were officemates in the Taichung District Courtroom 303, took their first and path-breaking action to target non-transparent case allocation, the essential mechanism for external manipulation.Footnote 39 By assigning cases to specific obedient judges to guarantee case outcomes, the president of the court not only gained monetary benefits, but also created an incentive structure to reward and discipline ordinary judgesFootnote 40 (TW201632). To change the dynamics, the reformist judges advocated for a democratic process—an annual judges’ meeting—to decide the rules for case allocation. They circulated a proposal among their colleagues, where the language was passionate with genuine normative concerns:

According to the Court Organic Act, art. 79 and 80… it is clear that case allocation should be decided by judges, the president of the court himself has no right to decide. But in fact … in the past 60 years, this is only on books but not in practice. Such a Taiwanese miracle! … Judges are experts of the law … but we take this illegal practice willingly. … How can the society trust a judge who neglects his own legal rights, how could he be capable of protecting others’ rights? We are even more worried that judges have no legitimacy to judge in a case unlawfully assigned. For all these reasons, many of us in this court, after careful considerations, decided this is the time to stand up to fight for judges’ self-image. Hence this proposal of annual judge meeting guideline. We hope our actions would wake public concerns for the judiciary from the whole nation, and all judges in all appeals would unite to bring a brighter tomorrow for our courts, soon!Footnote 41

They also pressured the court by an unprecedented move: they held a press conference and attracted considerable media attention.Footnote 42 This made the following judges’ meeting at Taichung District Court highly contentious, inviting much criticism of their maverick act:

self-governance … doesn’t have to trample others!Footnote 43 The timing [of the proposal] is questionable. Are the new judges here unsatisfied with the current case allocation, and intentionally agitate this self-governance movement? The self-governance movement is meaningless if it is led by personal motivations.Footnote 44

The discussion lasted for four hours and, after four rounds of voting, the reformist judges finally passed the proposal at 41 votes to 34 votes.

The call from Taichung was perceived as a revolution against the judicial hierarchy. As their action echoed many ordinary judges’ experience at the time, open support from other parts of the country soon spread out: 39 judges from the Taipei District Court signed an open letter and 56 judges from the High Court, of whom 18 were chief judges of the trial panel, also voiced support. Two of my interviewees, both of whom have been on the bench since the early 1990s, expressed similar recognition: a senior judge who was working at the Tainan District Court (in the south) recalled that many young colleagues thought very highly of the action in Taichung (TW201719), while another senior judge, working in a northern urban jurisdiction at the time, said “we all secretly applauded (with one thumb up)” (TW201722).

This bottom-up movement was later entertained by the Judicial Yuan, the central administrative body of the judiciary. The president of the Judicial Yuan formed a Judicial Reform Committee in 1994, while a number of reformist judges from Taichung joined the committee to express their concern. Effectively, the 1994 Judicial Reform Committee resolved in their third meeting urging democratization within the judiciary:

We suggest that the Judicial Yuan … request all courts, by an election of all judges and chief judges of trial, to organize a committee of case allocation and draft rules for case allocation, in accordance with Art. 79 of the Court Organic Act, to be presented at the annual judge meeting for approval.

Accordingly, the Judicial Yuan did issue an official letter to institute such a committee for transparent and democratic administration. Courts across the country hence began releasing power to the judge cohort in respective jurisdictions to make rules for case allocation (TW201632; TW201719).

In addition to rejecting administrative control, the reformist judges also mobilized for a constitutional protection of judicial budgetary independence. The first attempt took place in 1994: reformist judges from the Taichung District Court Room 303 and another group of judges from Taipei mobilized half of the whole judicial population across the country (572 out of 1,107 judges at the time) to sign a collective petition to the National Assembly,Footnote 45 the legislative body amending the Constitution at the time. Ten judges later attended the Assembly to formally petition for this. The attempt failed, however, and it was not until three years later in yet another round of constitutional revision that the Taiwanese judges successfully acquired support from the ruling party. As a senior judge witnessed:

Because of the corruption case of Wu Tse-yuan, national press published good stories about the judiciary for about six months. I said to another judge that this is good timing to push for the constitutional amendment of judicial budgetary independence. We thought, we need to take a look at the 1994 proposal. So we went down to Taichung to meet the group of judges who initiated the previous amendment. Then we assigned different people among ourselves to go to the three major political parties. We also asked the Judge Association to formally visit the speaker of the National Assembly. After the three major parties confirmed their support, we went to the lawyers and NGOs; for example, the Judicial Reform Foundation (JRF) joined the petition after we went to them. The momentum comes from within the judiciary (TW201722).

The amendment passed with 251 votes out of 257 representatives in attendance. The reformist judges accurately saw a policy window when the then ruling KMT was willing to show support for judicial reform.Footnote 46 The cross-sector and inter-jurisdictional mobilization clearly demonstrates that these judges are purposeful actors who take initiatives to consolidate their independence from the party-state control, and they aptly utilize opportunities along with the ongoing political transformation.

Two pieces of evidence further suggest that Taiwanese judges are ideationally driven with a clear ideal instructing their strategies, whose actions are not determined by their material interest or shifting political opportunities. First, counter-factually, the reformist judges could have not acted and gained personal benefits. Or, to say the least, potential material interests available to them were the same as to other judges, and the only difference was that the reformists chose to act against the incentive structure because of normative commitments. An exemplary case was the senior judge in TW201632: he was first presented with an invitation of monetary interest—an investment opportunity that guarantees double returns. He turned it down because of his wife’s reminder: “it sounds like bribery.” Later, a high-profile case was assigned as an indirect gesture for him to show loyalty:

The chief judge of my trial panel came to me, “you be cautious, and deal with it properly and diligently.” So I did. After being diligent for three months, I was transferred to another division, away from the case. The chief coming to me probably implies that the president showed concerns. But the chief didn’t tell me which party I should be proper and diligent to! [laugh]

He got connected to other reformist judges after he was demoted, because they shared an office on “a shabby corner.” Later, this interviewee became one of the key figures in the network.

Second, the decision to choose collaborators in politics was guided by principals. Judges co-operated with whoever supported their cause, despite the politicians’ official party affiliation. This was evident in their lobbying effort where they reached out to all three major political parties at the time. Additionally, when it came to supporting a candidate of the president of Judicial Yuan, a key nomination to carry out judicial reform in the late 1990s, reformist judges were open to both a traditional KMT bureaucrat and a non-partisan academic (TW201623). This stands in stark contrast to the liberal lawyers: “the JRF did not trust Shi Chi-yang to chair the judicial reform forum, because Shi is a KMT party-official” (TW201623). In this sense, reformist judges were skilful political actors, fully aware of the fact that even the KMT party-state was heterogeneous and some politicians could be their collaborators. Clearly, Taiwanese judges developed political strategies to serve their ideals; they worked with the shifting political landscape to secure an ideal of independence in response to the manipulation they witnessed.

It would be inaccurate, however, to say that the reformist network succeeded in all their reform attempts. Some reformist judges did enter authority positions (whereas others simply remained on the bench, TW201623; TW201632; TW201728), but they encountered various pushbacks when putting their reformist ideals into practice. For example, when one of the key figures, Judge Lu Tai-lang, was promoted to directorship of the personnel department in the Judicial Yuan to carry out organizational reform, his promotion was criticized so heatedly that the Control Yuan, the ombudsman agency, issued a report targeting him: “Ever since Judge Lu assumed office, his work on personnel business … no positive outcome is observed, but negative impact has occurred.”Footnote 47 His intended reform policy to set a term limit on chief judges of the trial panel, delinking seniority and professional capacity to prevent case meddling, also experienced strong counter-mobilization from senior judges in the High Courts.Footnote 48 Following Lu Tai-lang, another reformist judge, Chou Jan-chuen, succeeded the directorship to continue personnel reform, but similarly experienced great pressure. The pressure even went up to the president of the Judicial Yuan, who intended to support Chou but faced extensive opposition (TW201623; TW201710). An anecdote shows the degree of pressure: one day, the president was literarily “cornered” in his office by some senior judges before leaving work, to make him promise to let go of the internal reform guideline (TW201710). Indeed, the reformist network’s attempt to transform the personnel structure was compromised considerably. Their experience after entering the judicial administration accurately shows not all ideals were elevated, but judicial independence is the normative commitment, among others, that survived and was institutionalized in the Taiwanese judicial community.

The ideal of independence was consolidated in the judicial community. A collective petition against a forced transfer case in 2012 nicely demonstrates this recognition among Taiwanese judges. Over 900 judges (out of 1,900 judges in the country at the time) signed an open letter to support two judges who were forced to transfer by the Judicial Yuan. The incident began with a serious disagreement between the two judges in Hualien over a physical-assault case involving local politicians. The presiding judge approved the extension of detention of the defendant, while the chief judge of her trial panel challenged her decision. The presiding judge, after having heard rumours about the chief judge receiving a bribe, openly claimed that the chief’s request was influence peddling, which the chief judge categorically denied. The confrontation became so severe that the Judicial Yuan stepped in to force the two judges, against their will, to transfer to two different district courts away from Hualien. The forced transfer evoked great contention and concern, especially from the lower ranks of the judiciary. When the Judicial Yuan sent the drafted transfer decision to the Personnel Review Committee for approval, six judge representatives from district courts walked out of the meeting to protest. Despite the walkout, the Personnel Review Committee still voted in support of the transfer, which quickly led to an appeal from the two judges and huge criticism in the community nationwide. In only three weeks, over 900 judges signed a joint petition “opposing the unjustifiable transfer” to support the two judges. And the committee re-reviewed the case. This recent incident, evidently, shows the scale, speed, and intensity with which Taiwanese judges react to a potential breach of judicial independence. To resist administrative manipulation has become their core identity, and also the only identity that could call out the bottom-up collective momentum.

3.3 Prosecutor: Spokesman for Justice

For Taiwanese prosecutors, justice is an indispensable professional norm. Particularly, checking the abuse of power is at the core of this ideational pursuit. While the pattern of formation, mobilization, and dissemination is similar to their judicial counterparts, Taiwanese prosecutors’ normative commitments come through interest-based requests, including securing resources for investigation and status protection as “judicial officer (司法官; Sifa Guan).” Targeting the KMT’s clientalist party-state in the 1990s, a small group of reformist-minded prosecutors successfully aligned in 1998 and mobilized to break the top-down administrative control and lobbied for institutional support to prosecute abuse of political power. The network of the Prosecutor Reform Association (PRA) plays a critical role in setting the agenda and lobbying for legislations reforming the procuracy, while many key figures in the PRA network lead a number of prominent, if not legendary, corruption investigations in post-transition Taiwan, including the charges of three democratically elected presidents.

Prosecutors faced tight party-state control for both institutional and political reasons. Taiwanese prosecutors were long held in the top-down commanding chain and personnel control until the late 1990s, and their action to collectively challenge the party-state came much later than lawyers (in 1990) and judges (in 1993–94). Unlike Taiwanese judges who were able to appeal to the textual support for independence, prosecutors had limited space in crime investigations because chief prosecutors in local offices have the authority to assign cases, supervise the progress, and review their performance for potential promotion (Arts 63, 64 of Court Organic Law). The unitary commanding system was designed to concentrate resources to serve criminal policy objectives, but it also allows political influence to trickle down from atop. It was thus difficult, and empirically futile in two individual attempts in 1989, for Taiwanese prosecutors to exercise their prerogative to investigate and prosecute abuse of power.Footnote 49 In the mid-1990s, however, “collective but isolated reform networks started to emerge” in different parts of the countryFootnote 50 where small but tightly connected teams of prosecutors successfully targeted local corruption, such as vote-buying and pocket lining, inflicting KMT’s clientalist ties at the county level. Many of these forerunners were under the age of 35 at the time, and deeply concerned about political intrusion in the procuracy, as well as prosecutors’ institutional status as “judicial officer,” which suggests independence for case investigation and political neutrality.Footnote 51

In May 1998, taking the opportunity of an official business meeting of the High Prosecutors’ Office, the PRA abruptly announced its inauguration and declared actions to be taken to mobilize local prosecutors for internal democratization:

We announce the following reform agenda: (1) we defend prosecutors’ status as part of the judiciary, (2) we request the right to select fellow prosecutors for our own investigation team, (3) we want to recommend our own head prosecutors in local offices to prevent pork barrel politics, and (4) we request a periodical, bottom-up evaluation of our Chief Prosecutor so his case assignment and supervision can be held accountable by his subordinates.Footnote 52

In another public statement, entitled “Give Me a Lever and I Can Move the Earth,” distributed two weeks earlier by the same group of reformists, the normative commitment was even clearer:

providing prosecutors with ample manpower, material resources, and status protection, so they would have space to investigate crime. Our prosecutors have long been fighting alone … with limited support from other agencies … face great pressure from elected officials and our superiors … the reason why we still struggle forward is our identity as a judicial officer, this sentiment from the bottom of our hearts. If our countrymen hesitate to provide support and further take away our judicial status, this is no different from forcing this species of prosecutors to go extinct in the field of criminal investigation! And this arena of criminal investigation will be under the shadow of a police state! … Archimedes once said, “give me a lever, I can move the earth;” and we prosecutors proudly state: give us ample resources, and we can leave no corruption unturned in the whole republic!Footnote 53

Evidently, Taiwanese prosecutors’ collective ideal to “leave no corruption unturned” was provoked by the political control of the party-state, while the interest-based requests of status protection and resources were connected to this pursuit of justice as a prerequisite. The reform agenda of personnel independence also served as a necessary condition of corruption investigation for Taiwanese prosecutors, as this head prosecutor explained:

We [prosecutors] want to be judicial officers not because of the benefits but independence. We have to avoid the situation where the President and the Minister of Justice can simply summon you in their office and ask you to brief them your case (TW201625).

Clearly, while both Taiwanese prosecutors and judges strove to peel off the party-state control, independence was instrumental to prosecutors but existential to judges.

The prosecution of corruption and the corresponding prerequisite of personnel independence have become the two cornerstones of the reform agenda ever since. Despite different political conditions in the first two decades of the twenty-first century, including three party turnovers, two lines of legislation promoted by the PRA network consistently reflect their “concerns about big structure, in relation to power, to allow prosecutors to check power” (TW201726). First, to institutionalize their effort curbing maladministration after the KMT lost the presidential office in 2000, the reformist prosecutors quickly convinced the new Ministry of Justice to set up five offices of the Special Investigation Centre of Corruption in the same year; subsequently in 2006, the reformist prosecutors successfully lobbied both political parties to legislate the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) into the Court Organic Act. In the following decade, the SIU prosecuted a number of high-profile tycoons and government officials.Footnote 54

Second, to neutralize the top-down bureaucratic control, the PRA network pushed for the democratization of the personnel system. Two important pieces of legislation were passed in 2006: first, the national prosecutor general is to be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Parliament, conferring democratic legitimacy on the national director of prosecutors; second, internally, the Personnel Committee of Prosecutors is to be composed of nine nationally elected prosecutors and eight officials appointed by the ministry and the prosecutor general. This legislation disempowered the minister of justice to the extent that the minister lost the absolute leverage to trade positions. Later, in 2015, to further limit the minister’s discretion in selecting head prosecutors, a third-generation reformist prosecutor even filed a lawsuit against the Ministry of JusticeFootnote 55 (TW201636). In another step forward in 2017, after yet another party turnover, the minister announced he would approve all personnel decisions confirmed by the Personnel Committee, essentially releasing her power to a semi-democratic institution over which she has no full control.Footnote 56 Indeed, bottom-up democratization of internal personnel control is a continuous development where Taiwanese prosecutors incrementally decentralize the minister’s power to protect themselves from top-down political manipulation, so that they can impartially carry out investigation and check abuse of power without interference.

Commentators familiar with Taiwanese politics may argue against the advancement of the prosecutors’ pursuit of the ideal of justice, especially between 2008 and 2016, when the KMT was back in power, when the political instrumentality of the SIU was discernible. However, attempts to instrumentalize the prosecution for the interest of individual politicians are, and will always be, present in politics; in fact, the attempts precisely constitute the structural constraints from which prosecutors demonstrate their agentic pursuit. It is hence imperative, first, to seek empirical evidence if, and where, Taiwanese prosecutors show consistent logic of action to resist such instrumentalization under different political containment. It is the presence of resistance, not the success of resistance, that indicates prosecutors’ normative commitment. Second, how such action, allegedly out of the pursuit of an ideal, is received by the prosecutors’ community is another important piece of evidence. As the following analysis aims to argue, a second, even third, generation of “reformist prosecutors” clearly passes on the ideal that prosecutors should pursue justice to check power, and there is also evidence suggesting the collective support of such an ideal.

To begin with, the PRA network has always been clear about their fundamental concern with abuse of power, irrespective of the party affiliation of the incumbent power. That is, prosecutors who commit to prosecute corruption inevitably clash with the incumbent party, not just the KMT party-state. The most dramatic instance was SIU’s prosecution of the former Taiwanese president, Chen Shui-bien,Footnote 57 in 2008. This is ironic because SIU was founded and signed into law during Chen’s term with his ruling party’s support, and the lead prosecutor of this case was Chen Rei-ren, one of the founders of PRA, also known as a supporter of Chen’s party when it was still an illegal opposition (黨外; dang wai) during the martial era.Footnote 58

The PRA network went into conflict with the Chen's ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 2001, one year after Taiwan experienced its first party turnover in which DPP assumed office. A “Saturday Night Massacre”Footnote 59 incident clearly revealed the dynamics: the DPP, once in opposition challenging single-party rule, made the same attempt to instrumentalize the procuracy when it became the ruler. Having initially trusted the reformist prosecutors as their investigation defeated KMT’s local connections, the DPP soon needed the prosecutors to tone down because DPP was a minority government and “Chen Shui-ben decided to fraternize the KMT localists” (TW201726). As the PRA network resisted such political will, President Chen ordered the minister of justice to remove those disobedient chief prosecutors to set an example. The removal took place in April 2001, and the backstage story sounded very much like what Nixon did during the Watergate scandal:

President Chen Shui-bien gave an ultimatum to the Minister of Justice, “if you don’t remove Chief Prosecutor Huang Shih-ming, you’re the one I’ll remove!” … [so] the Ministry of Justice transferred a large number of Chief Prosecutors nation-wide, including Huang in Taipei (TW201726).

The PRA prosecutors—many served in the SIU at the time—were furious and collectively quit. This brought pressure to the politicians, who came to appease: “Because in 2001 there was the national election of legislators, crucial to DPP, they needed prosecutors to wipe out KMT’s local influence. Prosecutors can limit KMT’s influence from getting elected, or KMT candidates would face election lawsuits afterwards” (TW201726).

This experience accurately shows that the political instrumentalization of prosecutors, no matter which party, rules. Nevertheless, the reformist prosecutors clearly resisted the political will, and strategically co-opted to achieve their normative pursuit: prosecution of corruption.

Admittedly, during the 2008–16 KMT administration, the SIU was markedly contained: on the one hand, SIU showed a tendency to “investigate the green (DPP) but not the blue (KMT)” (TW201714). On the other hand, within the prosecutors’ community, SIU in this period was known to be under detailed, hands-on supervision:

they can’t meet with journalists at all, whenever they leave the office they need to ask for leave; and there’s this prosecutor [identified the name], wasn’t even allowed to go to Hong Kong to look for information for the arms procurement scandal of La Fayette frigate …. The General Prosecutor strictly controls SIU with a political objective, KMT’s big policy: to suppress the prosecutors (TW201726).

Given the constraints, lock-in effects to check incumbent power were still identifiable from SIU in 2011 and 2012. SIU prosecuted: (1) an embezzlement case, investigating secret accounts at the National Security Bureau, which targeted another former President Lee Deng-hui and the “KMT head treasurer” Liu Tai-ing and (2) a bribery case of a KMT official Lin Yi-shih, who was the party vice president and the Secretary-General of the Executive Yuan at the time of prosecution. Although the SIU operation did not markedly threaten the administration, the prosecution of the embezzlement case still led to “President Ma Ying-jeou’s discontent, because the investigation essentially challenged their power-money structure” (TW201726). Arguably, the institutionalization of a special investigation still effectuated the prosecutors’ role in restraining the incumbent power even during the waning era.

Another important piece of evidence is identifiable support from within the prosecutors’ community for the continual attempts by different generations of reformist prosecutors. In 2015, prosecutor Tsai Chi-wen filed a lawsuit against the minister of justice to challenge her personnel discretion. Tsai, an elected representative of the Personnel Committee from Shu-lin District Prosecutors’ Office, brought a list of candidates endorsed by his fellow prosecutors to be promoted to head prosecutors and the High Prosecutors’ Office. But the Committee insisted on adding more names to the list so the minister had more options to select from. Tsai hence sued for an injunction to stop the minister from selecting, because the law allows no discretion. As he later stated in a public interview:

Article 90 of the Judge Act states that the minister can only “approve” but not “select” from the list proposed by the Committee. This is so because art. 90 comes from art. 59–1 of the Court Organic Act, revised in 2006. The Prosecutors Reform Association pushed for this revision, and I was a member then, so I know the legislative debate very well. … The PRA and the then Minister met each other in half way where the minister can choose chief prosecutors from a short-list with twice the number of the vacancies, but not for other positions, including head prosecutors of the district and high prosecutors’ offices …. The minister can only approve and announce. No space to intervene.Footnote 60

Tsai’s action and statement clearly indicate his intellectual ancestry succeeding the pursuit of the PRA’s ideals. A prosecutor who went through professional training with Tsai also situates him in the PRA network:

The PRA network started with people like Chen Rei-ren (class 24 at the Academy of Judiciary), Chu Chao-lian; then, like Chen chih-ming (class 30); five years later there’s Tsai Chi-wen (class 41) and Lee Wen-chieh (class 43). Approximately every five years a cut-off (TW201636).

Evidently, Tsai is identified as a third-generation reformist prosecutor taking actions in a different institutional arena, continuing the idealist struggle that lasted almost a decade. Ideationally driven, Tsai frankly stated that his election to the Personnel Committee was an act of resistance to the abuse of power:

I ran for the election because of the Sunflower Student Movement case in March 2014. A prosecutor filed to detain the student leader Wei Yang, but the moment [the prosecutor] filed the request, both the Judge Forum and the Prosecutor Forum had posts asking the judge not to approve the detention warrant … and the judge indeed denied it, reasoning “insufficient criminal evidence.” In other words, the prosecutor knew the evidence was not enough to detain the student, but he requested it nonetheless. I highly suspect the prosecutor was under political pressure. … One prosecutor made a mistake, all the prosecutors bear the bad name. So I ran for the Committee to challenge the minister’s illegal selection prerogative. I wanted to voice for prosecutors like me, who take our responsibility seriously.Footnote 61

Tsai was elected “with the highest margin as a first-time contender,” as a senior prosecutor recalled: “his public statement was widely and well received” (TW201726). Support came from all across the country, as another mid-career prosecutor identified Tsai as “the representative at-large” (TW201625) and another young prosecutor also showed similar respect to Tsai (TW201626).

It is empirically challenging to verify the impact of ideas, especially when actors face great external constraints. For those politically active prosecutors in Taiwan, they do experience political containment, and their attempts to establish, disseminate, and consolidate their normative commitments are shadowed, if not covered, by continuous instrumentalization from the incumbent political power. However, evidence still reveals the consistent presence of ideationally driven pursuits within the system and with numerous case investigations, both as individual cases and as a lock-in institutional effect by different generations of reformists who are linked intellectually through a particular network.

4. CONCLUSION

Professional identity is made, not inborn. For those politically active legal practitioners, their professional ideals originate from their political actions in relation to the incumbent rule in a special period of state power reconfiguration. Critically, these norms are built in response to the incumbent power as a source of legitimacy, not only for mobilizing the legal community internally, but also for establishing validity in a transforming society. Different legal professions, as they are situated differently in relation to the ruling power, develop different resistance models and rationales, resulting in variations among intra-profession ideals. The Taiwanese legal professions exemplarily demonstrate how ideals are embodied during democratization, and how different normative commitments are triggered by each respective model of state containment. Resisting the authoritarian state imposing a martial rule upon Taiwanese society, a closely linked network invariably emerged in all three legal professions as “civilian” “reformists” to challenge the party-state, yet it acted upon different reform objectives in accordance with their respective ideals to transform the legal institution. It is empirically intriguing that the three networks, although similar in mobilization pattern and principally identical in defying political intrusion, did not co-ordinate with each other during the founding moments of their liberalization. This is, however, theoretically consistent, as their respective relationships with the authoritarian state differentiated the institutional areas and focus of action for them, hence their trajectories were separate and independent, and only intersected later in other areas of judicial policy-making.

To situate the political identity theory in the literature of the legal profession, there are two schools of thought that call for attention.Footnote 62 The first alternative explanation is the professional education through which legal practitioners acquire their professional identity, which may be political in nature, in law schools and training institutions. The empirical story stands in contrast, however, that both formal college educationFootnote 63 and the judicial training instituteFootnote 64 in Taiwan at the time encouraged conformity to authority and indifference to politics. Little can we learn by looking into the formal curriculum and the campus lifeFootnote 65 to understand why certain lawyers, judges, and even prosecutors still took the political actions they took, or why they acted at all. In fact, as earlier analysis suggests, the differentiated educational fields are themselves part of the state containment that constituted the environment which actors fought against. The second alternative explanation is client influence; that is, legal practitioners are inclined to stand for their clients. Lawyers logically develop a political orientation as the people’s advocate, and prosecutors, employed by the state, defend policy rationales to sustain social stability and control crime. Clientele affords a strong framework; however, it falls short in three regards. (1) judges serve no clients, yet they still demonstrate strong mobilization capacity and will to take a political stance. Clearly, clientele provides very limited, if not no, explanatory power for judges’ motivation and transformation. (2) Prosecutors do serve the state; nevertheless, those politically active prosecutors in Taiwan clearly contradicted the state, and in fact acquired legitimacy and momentum from such contradiction. This is so because it should be a Rechtsstaat that prosecutors serve, yet an authoritarian party-state is not a legitimate client for them to pay loyalty. The gap between “what the state should be” and “what the state is” allows, even compels, some prosecutors to make a normative pledge defying the political reality. In other words, for those politically active prosecutors, they are not influenced by their clients; they are motivated by their own expectations of their clients. (3) Similarly, indeed, lawyers serve the people and are influenced by their clients. Yet, despite variations in their clientele, only one political narrative came out to bond the network in Taiwan and successfully marshalled and sustained support. A simple historical fact limits the explanatory power of the clientele theory: the leader of the ACL, lawyer Lin Ming-sheng, was a patent lawyer who served mainly the electronic manufacturing services industry. His corporate clients had no confrontation with the authoritarian state, and his services concerned no political rights. In fact, many ACL members were corporate and intellectual property lawyers in commercial law firms. They served enterprises, not individuals, and some were not even litigators. While lawyers in both hemispheresFootnote 66 jointly and willingly claimed the same political aspiration, an analysis tracing their actions and words captures the underlying theme more accurately than the clientele theory.

In conclusion, the Taiwan experience, by identifying the political origins in the critical juncture of power transformation, has implication for jurisdictions in Asia and beyond that similarly experienced fundamental power reconfiguration in recent decades, despite the direction of political liberalization. It is the actions during a period of political uncertainty that define the professional identity and shape the legal professions’ interpretive focuses, leading to the norms they uphold and the corresponding normative roles they should take in their respective jurisdictions. It should be noted, however, that the interpretive framework they act upon is an overlapping but independent framework from local politics, social and economic struggles. In other words, law is an independent normative frame for the legal profession to draw actions from. The legal profession may unite to resist political manipulation but later split on the extent to which the state exercises power to combat terrorism; or they may all disapprove of a colonial system but agree to different degrees of legitimacy that a representative government can claim in installing social stability. It is the political position that legal professions occupy during state transformation that sets the ideational dimension for them and critically determines the nature of their attitudes towards power. Examining the formative stage of professional identity, namely revisiting the historical context and the repertoire of ideas from which professionals select their ideals, is therefore essential, because it maps the political origins that explain why they prioritize certain norms, and how those norms inform their self-perceived roles in politics and society. ((Appendix))

APPENDIX

The fieldwork for this project was composed of four trips to Taiwan. The first trip lasted seven months from September 2016 to March 2017; the second trip was between June and August 2017; the third trip between December 2017 and January 2018, then the fourth trip in June 2018. The interviews are coded according to the order they took place in a given year: for example, TW201738 refers to the 38th interview I conducted in the year of 2017. While some interviews are group interviews, and may include interviewees of different professional backgrounds, I assign a letter to specify their vocation and a number to each interviewee, also according to the order I met them in the given year. The letter “L” refers to lawyer, “P” refers to prosecutor, “J” refers to judge, and “O” refers to other specialists. For example, TWL2017–26 refers to the 26th lawyer I talked to in the year of 2017, or TWJ2016–21 refers to the 21st judge I talked to in the year of 2016. The table below is a list of interviews and interviewees who are directly quoted in this paper, following the order they appear in the paper.

Table A1. Personal characteristics of interviewees