The continental shelf is valuable to coastal states primarily because under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [UNCLOS]Footnote 1 it offers exclusive control over the extraction of the petroleum resources found under the seabed of that zone. The sovereign rights of the coastal state apply equally to all other mineral resources and also to living resources belonging to sedentary species, but these are less valuable and are not the primary focus of this paper.Footnote 2 Where the prima facie entitlements to continental shelf of two or more states overlap, Article 83 of UNCLOS calls for the creation of a boundary, which would normally result in the area of overlap being divided among the states concerned, so that each can exercise its exclusive sovereign rights in the smaller (sub)area on its own side of the newly established boundary. States yet to delimit their boundaries may find difficulty attracting the investment needed to develop any resource known or suspected to exist in the area of overlap, as there is a higher than usual risk in such areas. This is that the investment will be forfeited if a later delimitation, whether by treaty or adjudication by an international court or tribunal, places the boundary landward, from the perspective of the host state of the investment, of the oilfield or a production site such as a well, so that it ceases to be part of that state's continental shelf. While a recent judgment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea [ITLOS] has confirmed that it is not unlawful for states to carry out such activities in areas yet to be delimited,Footnote 3 that is of little comfort to an investor on the “wrong” side of a supervening boundary, for there is no guarantee that the neighbouring state on whose continental shelf the facility ends up being located will allow the investor to continue operating it under its own laws. Petroleum resources in such areas of overlap may accordingly be left undeveloped for longer than otherwise comparable fields in areas of uncontested jurisdiction of a single state, where such risks do not arise.

This affects the coastal states of the Bay of Bengal, a body of water that is relatively unexplored but beneath which there are promising indications of hydrocarbon deposits.Footnote 4 It might not have mattered much in times when what might be called the wine theory of oil and gas held sway. Mirroring the rise in value of wine cellared as an investment, there was a solid body of opinion—though whether it was ever the orthodoxy may be doubted—to the effect that one should be in no hurry to recover resources, because the finite nature of petroleum deposits would lead to ever-greater scarcity and thus ever-higher prices.Footnote 5 It might thus be perfectly rational to postpone the settlement of the boundary dispute, as the petroleum would only become more valuable the longer it stayed in the ground. But whether or not this was ever actually true, it is much less likely to be so now, since it has been estimated that, if the international community is serious about keeping global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, only about a third of currently known reserves will be able to be developed.Footnote 6 Expressed another way, in 2017 there was twice as much technically recoverable oil as the world was expected to need between then and 2050.Footnote 7 This substantially raises the effective price to the states concerned of failing to settle their boundary. A petroleum deposit might be profitably developed today if the boundary were clear, and generate revenue for one of the states, but if resolution of the boundary is delayed long enough, the coming on stream of other energy sources less damaging to the climate may mean that the deposit in question falls instead into the two-thirds of reserves that will never be developed, reducing the asset to worthlessness. Against this background, there is unfinished business for Bangladesh, despite its apparent success in 2014 in completely delimiting its continental shelf boundaries with its neighbouring states India and Myanmar, thanks to the award of that year delimiting the boundary between itself and India handed down by an Arbitral Tribunal established under Annex VII to UNCLOS,Footnote 8 following the Bay of Bengal case decided in 2012 by ITLOS.Footnote 9

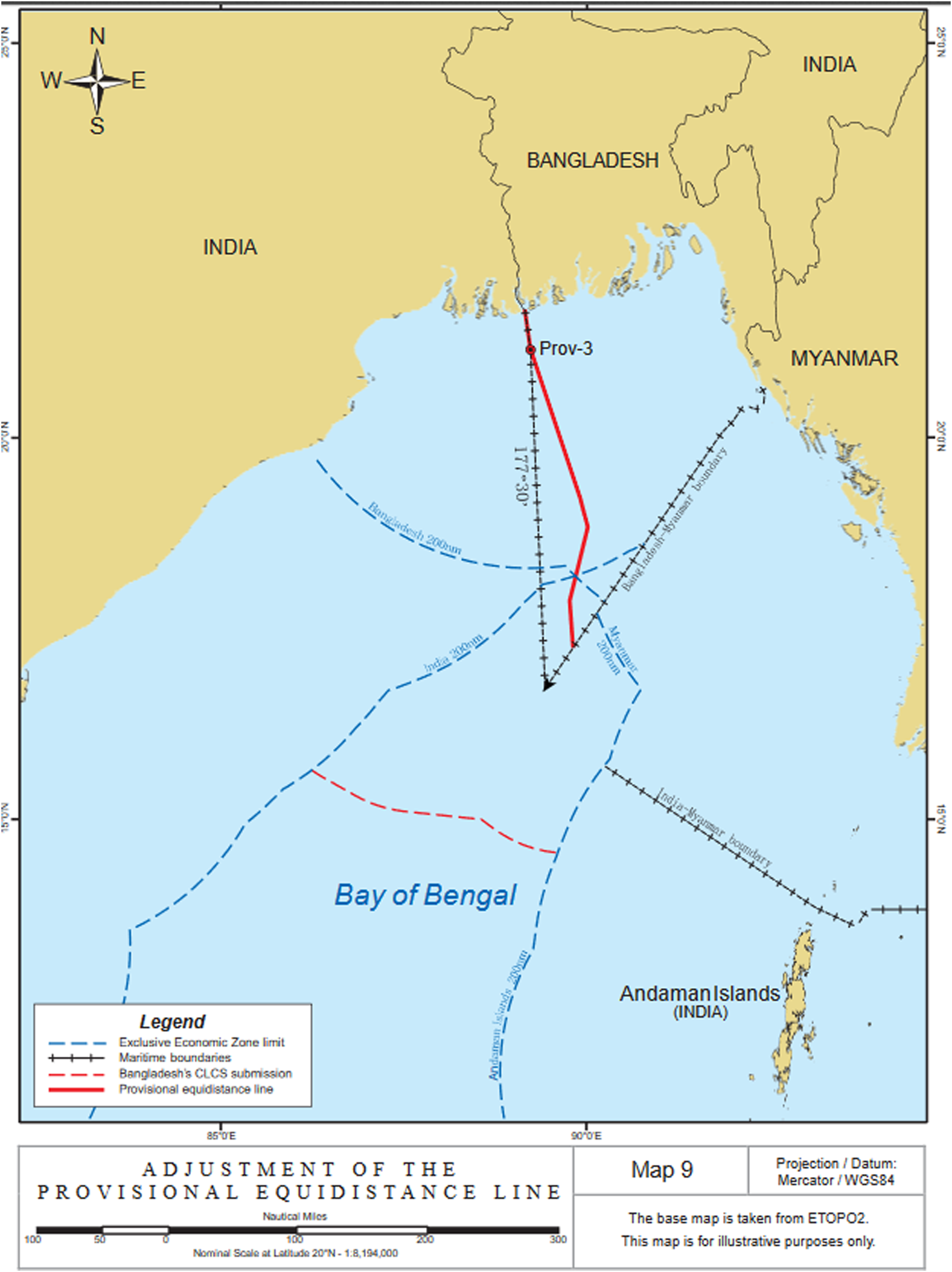

It is well known that Bangladesh, with a concave coast located at the northern end of the Bay of Bengal, has benefited in its maritime delimitation cases with its neighbours Myanmar and India from the willingness of courts and tribunals to eschew the use of equidistance lines when their effect would be to disadvantage the middle state in a row of three, as is inevitable in such a situation.Footnote 10 Less widely known, and the focus of this paper, are the obstacles still facing Bangladesh in exploiting to the full its continental shelf, even though its outer limit is now completely delimited as a combined result of the two cases. Map 1,Footnote 11 produced by the Tribunal that carried out the second in time of the two delimitations, illustrates the situation of the boundary in the later case meeting that laid down in the earlier one.

Map 1. Meeting of the delimited boundary lines of Bangladesh with each of its neighbours to form a single continuous outer limit for its continental shelf.

There are in fact two obstacles, one actual and the other potential. The actual obstacle comes about through the delay of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf [CLCS or Commission], a body created by Article 76, paragraph 8 of, and Annex II to UNCLOS, in reacting to the submission made to it by Bangladesh in 2011.Footnote 12 The first-mentioned provision sets out the process for establishing the outer limits of the continental shelf according to a complex series of formulae defined in the preceding paragraphs of the same Article, with which there is no need to trouble the reader here in detail. For the purposes of this paper, it is enough to note that paragraph 4 sets out two alternative formulae of entitlement that turning points on the outer limit line must satisfy, constrained by two further formulae in paragraph 5 that require points on the paragraph 4 lines to be shifted landward so as to be no more than 350 nautical miles from the territorial sea baseline, or no more than 100 miles beyond the 2500-metre isobath. The Commission is a technical body that receives submissions from coastal states believing that they can make a scientific case for a continental shelf extending more than 200 nautical miles from their baselines,Footnote 13 and in return makes recommendations to submitting states on the delineation of the outer limits of their continental shelves beyond 200 miles. Actual delineation remains the prerogative of the coastal state itself, but if its outer limit is “on the basis of” the CLCS's recommendations, it becomes “final and binding” and permanent once notified to the UN, though without prejudice to the delimitation of the continental shelf between opposite and adjacent states.Footnote 14 Although the text in the other authentic languages is ambiguous, the Russian text of UNCLOS confirms that it is not only the submitting state itself but also all other parties on whom such a limit is final and binding.

The potential obstacle lies in the fact that not only Myanmar and India but also Sri Lanka has made a submission to the CLCS in support of outer limits to its own continental shelf that produce an overlap with the part of Bangladesh's continental shelf within its delimited boundaries that lies more than 200 miles from the latter's baselines. While to date no adverse consequences have followed from this, that cannot be altogether ruled out until Sri Lanka's own outer limit is definitively settled.

A complicating factor is the interaction between outstanding maritime boundary delimitations and the effect of Annex I to the CLCS Rules of ProcedureFootnote 15 on the process for delineating the outer limits of states beyond 200 miles, which produce an area of overlap if they cross. Because no delimitation is required unless the primary entitlements of two or more coastal states do indeed overlap,Footnote 16 Part VI of UNCLOS on the continental shelf is constructed in a way that makes it logical for the CLCS process first to confirm, by way of recommendations under Article 76, that the entitlement of each of those states does in fact extend beyond 200 miles from its baselines, as this is what establishes the spatial extent of the overlap. By Article 83, a boundary can then be drawn to delimit the overlapping entitlements, either by treaty or, if agreement cannot be reached and the jurisdictional prerequisites are satisfied, by an international court or tribunal. Nonetheless, despite the absence of CLCS recommendations, among the reasons why ITLOS was prepared to extend Bangladesh's boundary with Myanmar beyond 200 miles, with the Annex VII Tribunal following suit for its boundary with India, was that in each case one state was blocking the other's submission under subparagraph 5(a) of Annex I to the Rules of Procedure.Footnote 17 Had ITLOS held back on this account, there would have been an impasse, with each of the two processes unable to begin until the other finished.Footnote 18 In fact there have been more than a dozen treaties settling maritime boundaries beyond 200 miles in advance of the CLCS process between pairs of states of which at least one was also party to UNCLOS,Footnote 19 and no other state has challenged the validity of any of them on this ground. It can be inferred that the states concerned are prepared to take the risk in delimiting such areas that the CLCS may later find that no overlap in fact exists, because only one of them, or neither, has an entitlement under the Article 76 rules. This is explicitly acknowledged in two of the delimitations, in instruments ostensibly not of treaty status, which are provisional, providing for adjustment of the boundaries should the risk eventuate.Footnote 20

The remainder of this paper examines the outstanding issues affecting seabed boundaries in the northern Bay of Bengal.Footnote 21 It does so in order to assess the prospects from a legal perspective of their resolution within a timeframe that offers some hope that, if resources exist in those areas that ceteris paribus are sufficiently easy to recover to fall within the third of reserves that global climate change regulation would leave exploitable, this can still occur in time to benefit Bangladesh and its neighbours. It first asks (Part I) whether the fate of Bangladesh's submission to the CLCS still matters. Part II concerns the need for co-operation between Bangladesh and its neighbours in the “grey areas” where its continental shelf as a result of the delimitation is subjacent to the exclusive economic zone [EEZ] of one or other of its neighbours, while Part III highlights the additional uncertainty affecting a small area where the two grey areas themselves overlap. In Part IV, a fourth state is introduced whose territory lies wholly adjacent to the southern part of the Bay of Bengal, but whose primary continental shelf entitlement extends well into its northern part, producing further overlaps with consequences needing to be worked through. Developments since the completion of the two delimitations are analyzed in Part V, supplemented by a brief Postscript at the very end, showing that co-operation has been hard to discern in the actions of at least two of the littoral states, and the need to revive that co-operation, and the relative ease of doing so, are the main conclusions drawn in the final Part VI.

I. CAN THE CLCS BE IGNORED?

The submission of Bangladesh to the CLCS when made in 2011 was the fifty-fifth such,Footnote 22 and it is likely to be some years before it reaches the front of the queue for the Commission's attention.Footnote 23 Submissions are considered in order of their receipt, except that priority is granted to new or revised submissions under Article 8 of Annex II to UNCLOS by states that have already made a submission and have received recommendations, to which the new or revised submission is a response.Footnote 24 In mid-2020, the most recent submission for which the Commission had constituted a subcommission to examine and make draft recommendationsFootnote 25 was that of India, the forty-eighth. Bangladesh's submission was thus seventh in the queue, but liable to displacement by any new or revised submissions, and any original submissions ahead of it in the queue that have been put aside by the Commission under subparagraph 5(a) of Annex I to its Rules of Procedure pending resolution of the relevant disputes. Parts V and VI below return to this matter, as the same provision, invoked by Bangladesh, also affects the fate of the submissions of both of its neighbours. Myanmar's submission is blocked in its entirety, while the Indian submission is the subject of an instruction to the subcommission by the full Commission not to examine the part of it relating to the Bay of Bengal.Footnote 26 By contrast, Bangladesh's own submission has been met with greater forbearance on the part of its neighbours. Although both of them have reacted to it with notes verbales (Myanmar reserved its rights,Footnote 27 while India observed that the Commission's consideration of it would be without prejudice to its own rightsFootnote 28), neither of these amounts to exercise of the veto that subparagraph 5(a) of Annex I creates for any state that objects to a submission,Footnote 29 assuming—though the weight of opinion is to the contraryFootnote 30—that this is consistent with UNCLOS.

This raises the question of whether it still matters what the Commission will say about Bangladesh's submission. If it does not, that would be because of the unique state of affairs that has come about through the outcome of the EEZ and continental shelf boundary delimitations with both of its neighbours. The later of these, that with India in 2014, produced a situation in which:

(i) a state's boundaries have been fully delimited with all of its neighbours in advance of the consideration by the CLCS of its submission, creating a single continuous outer limit of its continental shelf;

(ii) that outer limit is landward of the outer limit submitted to the CLCS; and

(iii) subject to the qualification in the next paragraph, neither of the outer limits abuts the seabed area beyond national jurisdiction [the Area] under the aegis of the International Seabed Authority [ISA] created by Part XI of UNCLOS.Footnote 31

The combination of these factors may mean that there is nothing to stop Bangladesh simply beginning to exploit the entirety of the area on its side of the 2012 and 2014 boundaries, as shown in Map 1 depicting the physical relationship of the various lines, or taking the necessary preliminary steps to do so, such as opening blocks in the area to bids by investors. Put another way, would any other state have grounds for objecting if Bangladesh does so? That would no longer be true of India and Myanmar themselves, with an important caveat to be considered below, thanks to the delimitations and Article 76, paragraph 10 of UNCLOS, quoted above,Footnote 32 which lays down that the provisions of Article 76 as a whole are without prejudice to the delimitation of maritime boundaries. The same applies to the ISA,Footnote 33 and to any fourth state, unless it sees some serious prospect that the part of Bangladesh's continental shelf more than 200 miles from its baselines will fall within the Area.Footnote 34 But for this to happen, ITLOS in the Bay of Bengal case, the Annex VII Tribunal in the Bangladesh v. India arbitration, and commentators would have to be uniformly wrong in their assumptions about the extent of continental shelves generally in the northern part of the Bay of Bengal, based on the existing state of scientific knowledge about the thickness of the sedimentary rock beneath the Bay, which was specifically remarked on during the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea.Footnote 35 These circumstances give grounds for confidence that enough is already known about the geology and geomorphology of the Bay of Bengal to be able to conclude that the Commission will eventually do one of two things. Either it may agree with the outer limits of the continental shelves submitted to it by Myanmar and India, which together enclose the whole of the northern half of the Bay,Footnote 36 or it may recommend that they run closer to land, but still in a way that sees those shelves separating the continental shelf of Bangladesh from either the Area or possibly—see below—the continental shelf of a fourth state.

If this surmise is correct, then the situation if Bangladesh proceeds without waiting for the Commission's recommendations is closely equivalent to what would have happened if it had simply not taken the trouble to make a submission at all. Another reason for ITLOS holding in the Bay of Bengal case that it had jurisdiction to delimit the boundary beyond 200 miles, despite both states concerned being yet to receive recommendations on their respective submissions, and expressly rejecting Myanmar's contrary argument, was that it can be deduced from Article 77, paragraph 3 of UNCLOS Footnote 37 that a coastal state's entitlement to its continental shelf does not depend on the establishment of its outer limits.Footnote 38 The same reasoning was then followed by the Annex VII Tribunal in the 2014 Arbitration between Bangladesh and India.Footnote 39 With the benefit of hindsight, it might hence be thought that the effort and expense of preparing the submission was wholly unnecessary, yet at the time this would have been a risky course of action for Bangladesh. The reason is that it is possible that ITLOS and the Annex VII Tribunal might instead have taken the same approach as the International Court of Justice [ICJ], which in 2012 refused to carry out the part of the delimitation of the continental shelves of Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the Nicaraguan baseline. It did this because the applicant, Nicaragua, unlike both parties in the Bay of Bengal case with which the Court drew an explicit contrast, had not yet made a submission.Footnote 40 There, however, again by contrast with that case, the available evidence in the absence of a submission was much weaker as to the existence of continental shelf entitlements under the rules of Article 76.

Thus, although under UNCLOS Article 76, paragraph 8 there is normally an incentive to make a submission, because outer limits based on the Commission's recommendations achieve legal certainty by becoming “final and binding” as against all other parties, Article 77, paragraph 3 ensures that, even if it does not make one, the coastal state still retains the whole of its continental shelf beyond 200 miles from the baselines, albeit without certainty as to how far it extends. In Bangladesh's case, the convergent boundaries of 2012 and 2014 now supply that certainty, as neither Myanmar nor India any longer has an overlapping entitlement to continental shelf in the area on Bangladesh's side of the boundaries. This appears to put paid to any need to wait for the Commission's recommendations on the outer limit submitted by Bangladesh, which are no longer relevant as it runs much farther seaward. With one exception, if any fourth state were to object, it would have to be on the basis that the area was beyond the limits of Bangladesh's continental shelf as defined in Article 76, a tall order indeed to prove, and one that ITLOS and the Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal have already rejected in being prepared to draw a boundary there in the first place. The exception is a single State, Sri Lanka, which may, if only very tenuously, still have an overlapping entitlement, as will be explained below. That apart, however, the probability that any part of the area landward of the adjudicated outer limits would fall outside Bangladesh's entitlement to continental shelf can reasonably be dismissed as negligible.

II. THE GREY AREA PROBLEM

Does that mean that licensing and exploitation by Bangladesh of the area landward of its adjudicated boundaries can now proceed without hindrance? Not necessarily, because of a side-effect of the remedy for the concavity of Bangladesh's coastline resulting in both the 2012 and 2014 boundaries departing significantly from the equidistance line (the line whose every point is equally distant from the nearest points on the respective baselines of the two states) in order to avoid the cutoff effect for Bangladesh that would have severely disadvantaged it vis-à-vis its neighbours. In such situations, it is geometrically inevitable that so-called “grey areas” will come into being, namely areas where part of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles of the state to whose advantage the departure from equidistance operates—in this instance Bangladesh—will be under not the high seas but the EEZ of the neighbouring state(s). This comes about because part of the area beyond 200 miles from the baselines of the advantaged state is still within 200 miles of the disadvantaged one(s), here Myanmar and India.Footnote 41 Only once that other state's 200 miles run out does the standard situation of the superjacent water column being high seas reassert itself. This is perfectly possible under the relevant provision of UNCLOS, which is expressed in neutral terms in this regard:

Article 78

Legal status of the superjacent waters and air space and the rights and freedoms of other States

1. The rights of the coastal State over the continental shelf do not affect the legal status of the superjacent waters or of the air space above those waters.

2. The exercise of the rights of the coastal State over the continental shelf must not infringe or result in any unjustifiable interference with navigation and other rights and freedoms of other States as provided for in this Convention.

In other words, grey areas, while not anticipated by the drafters, are not excluded either. This conclusion is reinforced by comparing the text of paragraph 1 with its similar but not completely identical precursor, Article 3 of the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf,Footnote 42 where the phrase “the legal status of the superjacent waters” is immediately followed by the specification “as high seas”. Thanks to the EEZ regime laid out in Part V of UNCLOS, the superjacent waters within 200 miles would ordinarily now be the EEZ of the coastal state if it has declared one, and this would clearly have been within the contemplation of the drafters.Footnote 43 It is possible that they assumed the EEZ in question would be that of the same state to which the continental shelf belonged, but there is reason to believe that any attempt to make a positive requirement of this would have met resistance.Footnote 44

The result this produces in the northern Bay of Bengal can be seen in Map 2.Footnote 45 The grey area covers 548 square nautical miles in total.Footnote 46

Map 2. Grey areas in which continental shelf of Bangladesh is overlain by the EEZs of Myanmar and India.

Despite the general conclusion above that Bangladesh faces little risk in releasing seabed areas beyond 200 miles but within its boundaries for exploration and exploitation in exercise of its sovereign rights over the continental shelf, in the grey areas, therefore, at least some further negotiation with its neighbours will be necessary before Bangladesh (or persons licensed by it) can embark on any kind of activity relating to its seabed. The fact that the seabed can be approached only through the water column under the jurisdiction of one or other of them is addressed in paragraphs 498 to 508 of the Award in the Bangladesh v. India Arbitration, which also draws on the equivalent parts of the ITLOS Judgment on the boundary with Myanmar. In particular, the 2014 Award quotes paragraph 476 of the earlier Judgment, which said that

[t]here are many ways in which the Parties may ensure the discharge of their obligations in this respect, including the conclusion of specific agreements or the establishment of appropriate cooperative arrangements. It is for the Parties to determine the measures that they consider appropriate for this purpose.Footnote 47

A little further on, in the last paragraph before the dispositif, it underlined that

[i]t is for the Parties to determine the measures they consider appropriate in this respect, including through the conclusion of further agreements or the creation of a cooperative arrangement. The Tribunal is confident that the Parties will act, both jointly and individually, to ensure that each is able to exercise its rights and perform its duties within this area.Footnote 48

The Tribunal also pointed out that, even though the EEZ carries rights over the seabed, those rights under UNCLOS Article 56, paragraph 3 are to be exercised in accordance with Part VI of the Convention devoted to the continental shelf,Footnote 49 which makes the Bangladesh seabed rights exclusive rather than concurrent and shared with its neighbours.

Because there are not many places around the world where this situation pertains, as the number of delimited boundaries going beyond 200 miles is rather limited, there is as far as the author is aware only a single precedent for how the states concerned might handle this overlap, namely the 1997 Perth Treaty between Australia and Indonesia.Footnote 50 Although the relevant provision, Article 7, is expressed abstractly in terms of “First” and “Second” parties,Footnote 51 the whole overlapping area involves Australian continental shelf under Indonesian EEZ. Thus it could theoretically advantage one side over the other, but despite some academic criticism to that effect shortly after the treaty was signed,Footnote 52 it seems even-handed in fact as well as in form, and may thus commend itself to Bangladesh and its neighbours as a model to be followed. Whether it does in fact serve both parties equally well may not be known until the treaty enters into force, but Australia has been sufficiently confident to invite bids for petroleum acreage in the area of overlapping jurisdiction, albeit in a location where only a water column boundary depends on the 1997 treaty, because the seabed boundary was already in place under an earlier instrument.Footnote 53 At all events, the subject matter of the 14 paragraphs of Article 7, if not their precise content or length, can serve as an indication of the issues that will confront Bangladesh and its neighbours in their co-operative management of the areas of overlap, to which they will need to develop their own solutions if they find those in the 1997 treaty unsatisfactory. Nothing in the text of the latter suggests that its suitability for other contexts is confined to situations where the overlap is between opposite rather than adjacent states.

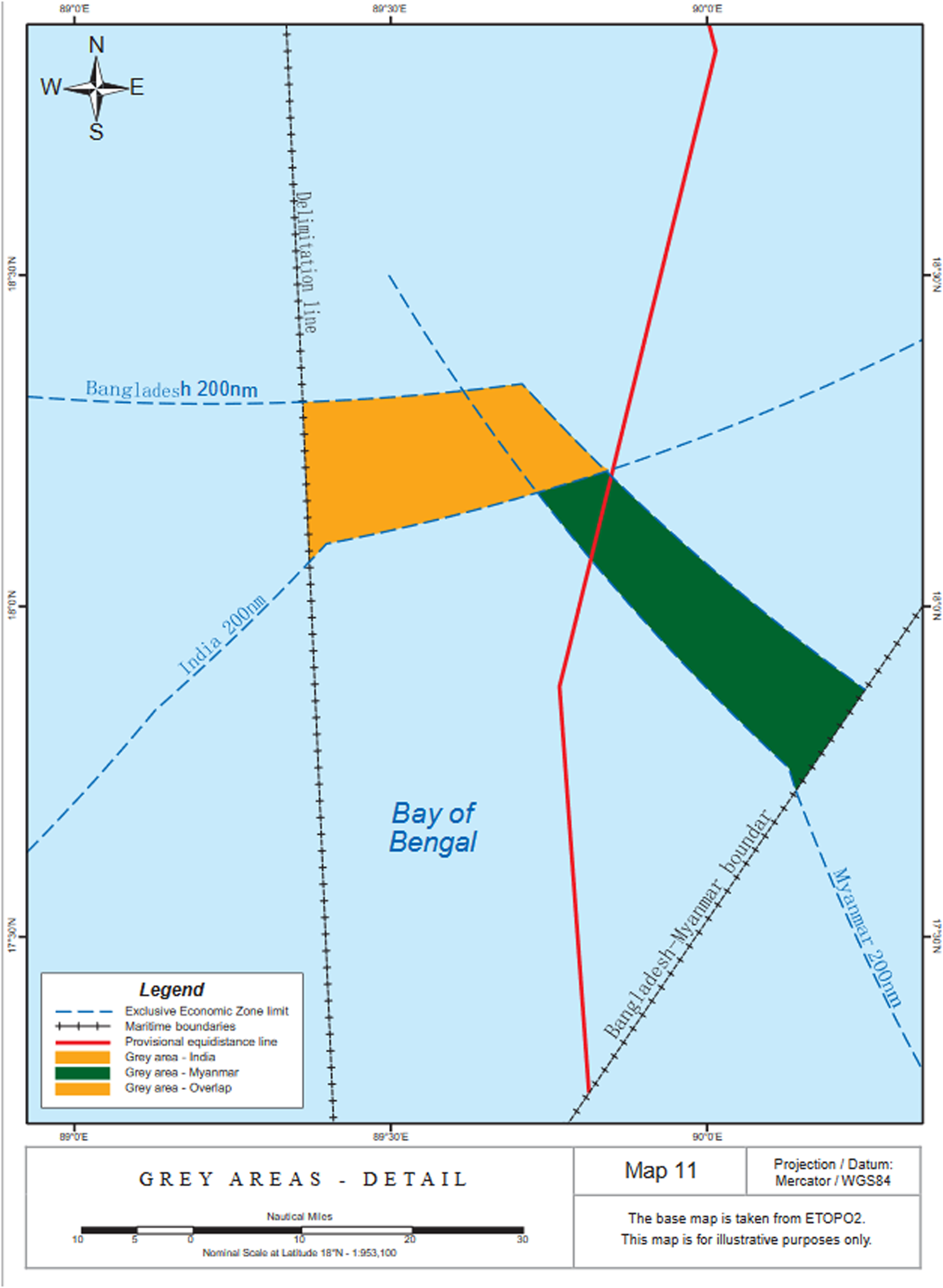

III. THE SPECIAL PROBLEM OF THE “DOUBLY GREY” AREA

The fact that the sovereign rights of at least three states are at stake in the northern part of the Bay of Bengal gives rise to an additional complication that is not present where only two states’ interests need to be balanced. Indeed there is an element of irony here that Bangladesh can move most easily to explore and exploit the most distant part of its continental shelf beyond 200 miles, where the superjacent water column is high seas, while the thorniest problem occurs in what is on average perhaps the closest subpart of it to land. This is what may be called the doubly grey area of 64 square nautical milesFootnote 54 where the two grey areas already described themselves overlap. The existence of such an area was noticed by the Bangladesh v. India tribunal in its Award, though it may not have adverted to the full ramifications of it in its brief observation that “[t]he present delimitation does not prejudice the rights of India vis-à-vis Myanmar in respect of the water column in the area where the exclusive economic zone claims of India and Myanmar overlap”.Footnote 55

If a negotiation needs to be had between Bangladesh and its neighbours to replicate or improve upon Article 7 of the Australia-Indonesia treaty before use of the continental shelf can proceed in a legally secure fashion, the practical effect of the doubly grey area is to delay this, because Bangladesh cannot know with which of Myanmar and India it has to negotiate the requisite arrangements until these two states have delimited their EEZ boundary with each other. Since this is likely to be linked to the delimitation of the boundary between their continental shelves south of the southernmost point of Bangladesh's post-delimitation continental shelf, that may not occur until their own submissions to the CLCS have been through the Article 76 process. This gives Bangladesh an incentive to lift the veto it has lodged against the examination by the CLCS of its neighbours’ submissions,Footnote 56 which as a result of the 2012 and 2014 adjudicated delimitations no longer appears to serve any useful purpose.

IV. THE UNNOTICED FOURTH STATE: SRI LANKA

Both the ITLOS case and the arbitration proceeded entirely on the footing that only three states had prima facie continental shelf entitlements in the northern Bay of Bengal; this applies equally to the pleadings of each of the parties and to the ensuing judgment and award. A fourth state, Sri Lanka, has however made a submission to the CLCS in support of a continental shelf encompassing almost the whole of the Bay of Bengal beyond 200 miles from any of the coastal states. That includes the whole area landward (from Bangladesh's perspective) of the outer limit presented in the Bangladesh submission and thus the whole of the smaller area on Bangladesh's side of the convergent 2012 and 2014 boundaries. This is shown on Map 3,Footnote 57 reproduced from the executive summary to Sri Lanka's 2009 submission, which predates by several months the institution of proceedings in the Bay of Bengal litigationFootnote 58 and thus was, or ought to have been, known to both parties from the very beginning.

Map 3. The outer limit of the continental shelf of Sri Lanka beyond 200 nautical miles from the baseline submitted to the CLCS. The submitted line begins at point A on Sri Lanka's 200-mile line and ends at point B 200 miles from the baseline of the nearest state (India's Nicobar Islands) and then follows the faint 200-mile line anti-clockwise around the Bay of Bengal in order to meet Sri Lanka's 200-mile line again to produce a complete polygon.

Neither the Indian Note of May 2010Footnote 59 nor Bangladesh's Note later the same yearFootnote 60 amount to objections to the consideration by the CLCS of Sri Lanka's submission, and Myanmar has not submitted any such Note. Sri Lanka's submission at the time of writing is one of those before a subcommission of the CLCS,Footnote 61 and no instruction was issued by the full Commission to the subcommission when creating it in 2016 to disregard any part of the outer limit submitted to it by Sri Lanka.Footnote 62 In the northern part of the Bay of Bengal Sri Lanka's submitted outer limit is not described at all in the executive summary of its submission, but Map 3 depicts it as the 200-mile line drawn from the baselines of the three littoral states. Accordingly, none of it is constructed, or needs to be, with reference to the formulae of Article 76, the integrity of whose application it is the Commission's task to safeguard. Even if the CLCS will hence not need to concern itself directly with that part of the outer limit, in practice it might still wish to pronounce itself in more general terms on the question of whether Sri Lanka's primary entitlement extends into the northern part of the Bay of Bengal, if not all the way to the 200-mile lines.

If this occurs, it would most likely be on the basis that there is doubt as to whether Sri Lanka has properly applied off its eastern coast the Statement of Understanding of 29 August 1980 annexed to the Final Act of the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea.Footnote 63 This is a special concession to states in the southern part of the Bay of Bengal, where the foot of slope featuring in both entitlement formulae of UNCLOS Article 76, paragraph 4, occurs close to land, but seaward of it lies a very extensive rise, much of which would be lost to the coastal state by even the more generous of the formulae, dependent on the thickness of the sedimentary rock. If on average it is 3,500 metres thick at the line drawn in accordance with that formula, with more than half of the continental margin lying seaward of it, the state concerned may instead follow the rise until the thickness of sedimentary rock drops to a kilometre, thus allowing it to enclose much more of the margin within its legal continental shelf.

In brief, the issue is whether this document is intended to exempt Sri Lanka from both paragraphs 4 and 5 of Article 76, inferred as Sri Lanka's approach,Footnote 64 or only from paragraph 4, as the CLCS Scientific and Technical Guidelines assume.Footnote 65 The answer is not self-evident: only the positive entitlement formula of paragraph 4 and not the constraints of paragraph 5 are mentioned in the Statement of Understanding; on its face, it thus leaves the latter provision intact. Two counter-arguments could be made, however: one is that paragraph 5 itself contains an internal cross-reference to paragraph 4 that thereby indirectly renders it inapplicable to Sri Lanka. The other is that it could perhaps be shown that that a narrow exemption from paragraph 4 only produces only a minor alleviation of the disadvantage to Sri Lanka by comparison with exemption from paragraph 5 in addition, which would strengthen the case for a purposive interpretation. This issue is no doubt being argued out in the forum of the subcommission, and although this occurs in camera, the outcome will become apparent when the subcommission finalizes its draft recommendations for the full Commission, or at latest when the final recommendations are ultimately adopted.Footnote 66

Even if Sri Lanka's view on this matter prevails, however, in reality the geography of the area all but ensures that its continental shelf will not ultimately go all the way to Bangladesh's 200-mile line, or even as far as the southernmost point of the line submitted by Bangladesh to the Commission. This is because there will need to be an extension of Sri Lanka's existing maritime boundary with India, whose land territory along with the maritime zone entitlements it generates lie between itself and Bangladesh, and that will put a practical northward constraint on Sri Lanka's entitlement. The existing boundary delimits only the EEZs of the two states and meets the 200-mile line between 11° and 12° N, as seen on Map 3, still well within the southern part of the Bay of Bengal as defined above.Footnote 67 In order for the extension of this boundary seaward to delimit the part of their continental shelves beyond 200 miles from their respective baselines to bend significantly northward in Sri Lanka's favour, there would need to be some very pronounced seabed discontinuity clearly marking the relevant part of the seabed as the natural prolongation not of India's land territory but of Sri Lanka's.Footnote 68 No such feature is visible on bathymetric charts or discernible from the colour scheme based on bathymetry in Map 3, as is consistent with the effect in the 2012 ITLOS case of the vast amounts of sediment beneath the Bay of Bengal masking the existence of a plate tectonic boundary. This masking effect led ITLOS to reject Bangladesh's argument that the area could not be considered the seaward extension of the land territory of Myanmar, which according to Bangladesh lacked any natural prolongation west of that geological boundary and was therefore deprived of any primary entitlement beyond 200 miles.Footnote 69 Rather, the pronounced change in direction of the eastern coast of India around 15° N would have the effect of pushing an equidistance line with Sri Lanka moderately but appreciably southward. This makes it all the more unlikely that Sri Lanka's continental shelf as finally delimited with India's mainland territory and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands on the eastern side of the Bay of Bengal will reach the 12th parallel of North latitude, let alone the 14th. On this basis, Sri Lanka's theoretical entitlement to a continental shelf extending into the northern part of the Bay is almost certain to prove little more than notional, leaving Bangladesh with two maritime neighbours, not three.

Meanwhile, however, as long as no such extension to the boundary with India exists, can Sri Lanka nonetheless prevent Bangladesh exploiting the outermost part of its “wedge” on the basis of this potential overlap of continental shelf entitlements? Though very unlikely to occur in practice, there seems to be no obvious theoretical basis to prevent it. To its credit, Sri Lanka has not used the opportunity created by Annex I to the CLCS Rules of Procedure to object to the consideration of any of the submissions by the three coastal states in the northern Bay of Bengal, and this suggests—though it can be no more than an educated guess—that any step Bangladesh might take in this direction would likewise not encounter trouble from that quarter. That may not be true, however, of the post-delimitation reaction by one of Bangladesh's neighbours, Myanmar, to the settlement of the boundary with the other neighbour, India, the final issue in this context that it is necessary to canvass.

V. HAS MYANMAR BEEN TOO CLEVER BY HALF?

Following the 2012 ITLOS Judgment, Myanmar could have been forgiven for thinking that the boundary dispute between itself and Bangladesh had been settled, and that the obstacle to the consideration of its submission by the CLCS would be removed by the lifting by Bangladesh of its objection. After all, by paragraph 10 of Article 76 the Commission's recommendations are without prejudice to the delimitation of maritime boundaries, as already noted above,Footnote 70 so that any such recommendation to Myanmar could not affect the boundary thus put in place, unless it were to fly in the face of all that is known about the Bay of Bengal seabed by denying it altogether any continental shelf entitlement extending beyond 200 nautical miles. As on each occasion when the Commission completes its work on a state's submission and is ready to move to the next submission, when this occurred at its 29th session in March–April 2012, the Commission went first to those submissions that had already reached the front of the queue but been held there because of objections from other states. It appeared to have Myanmar in mind, given the delivery of the Bay of Bengal Judgment a month earlier, when it noted that:

The Commission noted that the consideration of some submissions which were next in line had been deferred owing to the nature of statements contained in communications received in respect of those submissions. The Commission also noted that, in at least one case, the circumstances which had led to the postponement of the consideration of the submission might no longer exist. However, it was of the view that in order to be able to proceed with the establishment of a subcommission and the consideration of the submission, an official communication from the States concerned would be required.Footnote 71

Myanmar thereupon addressed a Note to the Commission asking that a subcommission be formed without delay to take up its submission.Footnote 72 Crucially, however, Bangladesh advised that it considered that the circumstances that led to the postponement of the consideration of Myanmar's submission still existed, as “Myanmar ha[d] not amended, modified or in any way altered its submission to take account of the judgment in the case”, and that the CLCS “should therefore not accede to Myanmar's request”.Footnote 73 Elaborating, Bangladesh indicated that, in its view, the boundary had not been fully drawn—what was missing was an endpoint, since the last segment of it was defined by ITLOS simply by a line of azimuth 215° from the last fixed point. Hence it could not be determined until the delivery of the award in the Bangladesh/India arbitration whether its dispute with Myanmar had been “fully and finally resolved”.Footnote 74

This does not seem convincing, and certainly ought not to have been so perceived at the time. The technique employed by ITLOS in the Bay of Bengal case of an azimuthal line of indefinite length to define the final segment of the boundary in circumstances where one or more third states have primary entitlements of their own in the area is a relatively common one, and it has not been suggested to date that courts and tribunals have thereby failed to resolve the dispute completely.Footnote 75 However long or short the azimuthal line (and it is clear from Map 2 that, if projected far enough, it would miss the east coast of India but make landfall on that of Sri Lanka), it is clear that the result of the adjudicated delimitation is that Bangladesh no longer has any continental shelf entitlement east of it, and Myanmar none to its west. In these circumstances, it is impossible to understand what harm Bangladesh might suffer from the examination by the CLCS of Myanmar's submission, with the azimuthal boundary line serving as a substitute—and more landward—constraint line in lieu of those in Article 76, paragraph 5 of UNCLOS already mentioned. For its part, however, the Commission was unmoved by Myanmar's entreaty: at a subsequent session it merely took note of the foregoing and other unpublished communications from both parties and “decided to further defer the consideration of the submission of Myanmar in order to take into account any further developments that might occur in the intervening period”.Footnote 76

At all events, however, without more, the delivery of the award in 2014 would have put the matter beyond doubt, as this was what Bangladesh in its own explanation of its position had identified as the step by which its boundary with Myanmar would become fully delimited, and the same must logically apply equally to its boundary with India. It might thus have been expected that, after this development, the examination of Myanmar's submission could at last proceed, and in due course, when its turn came, that of India too. This, however, is not what happened.

Instead, in 2015 Myanmar amended its submission in the light of the two boundary delimitation decisions, but did so in a clumsy and provocative way that if anything retrospectively vindicated Bangladesh's earlier ill-founded hesitation. The executive summary of the amended submission states that it is not based on new data superseding those underlying the original submission of 2008, and the co-ordinates of the six turning points of the outer limit are likewise unaltered. Rather, some additional argumentation is put forward to justify one turning point based on the 1980 Statement of Understanding.Footnote 77 It is also indicated that Myanmar's maritime boundary with India in the middle of the Bay of Bengal, i.e. an EEZ boundary resolving the overlap creating the doubly grey area, and southward of that a pure continental shelf boundary, will not be in place until the CLCS has established the two states’ primary entitlements via recommendations through the Article 76 process for both states.Footnote 78

The problem lies in the map produced by Myanmar (Map 4) showing the post-delimitation situation. Here the azimuthal line of the 2012 ITLOS Judgment is newly inserted, but extends barely if at all beyond Myanmar's 200-mile line, stopping well short of the reaffirmed outer limit line.Footnote 79 West of the adjudicated boundary line, the 200-mile lines of both Myanmar itself and India, which were part of the polygon defining the area enclosed by the outer limit line in the 2008 submission, have been removed and not replaced by anything else. The result is that there is no longer any polygon, so that the area of Myanmar's primary entitlement to continental shelf consequently becomes uncertain. Inexplicably, the 215° azimuth line has not been extended to meet and truncate the unchanged Article 76 line submitted by Myanmar, which would occur roughly halfway along the latter. Such an extension would have created a polygon of around half the size of that of the 2008 submission, and one to which Bangladesh could not credibly object as failing to respect the outcome of the 2012 delimitation.Footnote 80 Just such an objection, this time understandably, was now raised by Bangladesh. By a further note verbale to the Secretary-General, it claimed that Myanmar's amended submission “does not reflect the judgment of ITLOS” in the Bay of Bengal case laying down the 215° azimuthal line as the boundary “until it reaches the area where the rights of third States may be affected”,Footnote 81 nor the boundary in the Bangladesh/India Arbitral Award of 2014 expressed to end where it meets the 2012 boundary.Footnote 82 This leads to the complaint that “[t]he area claimed by Myanmar in its amended submission overlaps Bangladesh's continental shelf, including the … area which was awarded to Bangladesh by the ITLOS and the Arbitral Tribunal”.Footnote 83

Map 4. Myanmar's amended map demonstrating the outer limits of its extended continental shelf, with a newly inserted discontinuity in the outer limit preventing the creation of a polygon depicting the extent of its continental shelf over 200 nautical miles from the baseline.

A conceivable reason for the remarkable shortness of the mapped azimuthal line might have been that it was an attempt by Myanmar to take account of the enclosure of the whole of the Bay of Bengal beyond 200 miles by the outer limit in the Sri Lankan submission, as would be required by a literal reading of the dispositif (“may affect”). If so, though, this would surely have been mentioned by Myanmar in its executive summary, yet it was not. The point about the 2014 boundary is self-evidently correct, but its absence does not appear to create in itself any adverse consequences for Bangladesh. By contrast, the absence of a polygon means that it is not clear to what area if any Myanmar is laying claim, so that while it is possible that the last statement is an overreaction, by the same token one can see why Bangladesh expressed the view it did. This culminates in the final paragraph:

Myanmar's submission thus improperly seeks a recommendation from the Commission concerning areas that the ITLOS Judgment and the Arbitral Tribunal's award indisputably awarded to Bangladesh. For that reason, Bangladesh considers that for the Commission to take any action on Myanmar's submission would directly prejudice the rights of Bangladesh as adjudged and declared by ITLOS and the Arbitral Tribunal. Under the circumstances, Bangladesh maintains its objection to Myanmar's submission and respectfully submits that the Commission must decline Myanmar's request to establish a sub commission [sic] to examine its submission.Footnote 84

India shortly thereafter lodged its own Note,Footnote 85 which reaffirms its earlier one of 2009 before going on to invoke subparagraph 5(a) of Annex I to the CLCS Rules of Procedure. In addition, it

observe[s] that there are overlapping claims in the amended submission of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar with the claims of the Republic of India in the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured. It is, therefore, requested that pending resolution of the dispute, the amended submission of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar may be considered as under dispute[.]

Since the 2009 Note did not refer to either a dispute or this rule, the indirect effect of the 2015 amended submission has been to add to the veto of Bangladesh a second one from India. While this compounds the problem for Myanmar, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that on this occasion it has been the author of its own misfortune.

VI. CONCLUSION: THE NEED TO UNBLOCK THE IMPASSE OVER THE SUBMISSIONS

Although ITLOS in its 2012 Judgment did the States Parties to UNCLOS a service in advancing a cogent reason for breaking out of the stalemate created by the unfortunate effect of paragraph 5 of Annex I to the CLCS Rules of Procedure, it is to be lamented that subsequent poor and unnecessary choices by coastal states of the northern Bay of Bengal have in practice contrived to revive that impasse. None appears willing to take the first step towards untangling the knot of objections and counter-objections that has brought the Article 76 process to a halt. Judging by the Commission Chair's 2012 statement,Footnote 86 while Bangladesh could and, it can be argued, should have withdrawn its objection of its own accord after the Bay of Bengal Judgment of that year, all Myanmar for its part needed to do to induce this action by Bangladesh would have been to acknowledge the Judgment, which it has accepted, and ask the CLCS to take it into account in its recommendations. While their failure to take either of these steps is regrettable, as an alternative short of this it would still have been open to Bangladesh to modify its objection so that it applied only to any part of the Myanmar Article 76 line west of its intersection with the 215° azimuth boundary line, thereby automatically producing for itself the outcome it sought, rather than reiterating its objection to the entire submission. A similar modification of its Note regarding the Indian submission, confining its objection to the part of India's Article 76 line east of its intersection with the counterpart 177° 30′ azimuth boundary line in the 2014 Arbitral Award,Footnote 87 would likewise have fully protected Bangladesh's interests while allowing the whole of the remainder of the submission to be examined, rather than setting aside the significant portion of it that relates to the Bay of Bengal. These opportunities too went begging.

For Bangladesh in particular, the converging boundary lines of 2012 and 2014 have reduced the line it submitted to the CLCS, lying far to the south, to practical irrelevance. While in hindsight the submission risks being seen as an overly costly insurance policy, it is a brave adviser who would have counselled Bangladesh to stand back and let its neighbours do the work of convincing the Commission that the whole of the Bay of Bengal was part of the Asian continental margin, and then to demand its share of it by way of delimitation. As a counter-factual it can never be known, but Bangladesh appears to have been well served in both of its delimitations by having made its submission, even though receipt of recommendations on it remains years off, as in its absence there was some risk that ITLOS might take the same view about its authority to delimit the area beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines that the ICJ did at the first time of asking by Nicaragua. With both delimitations now behind it, though, there is advantage for Bangladesh in not waiting until it has reached the front of the queue, but instead moving promptly to put into place the practical arrangements with its neighbours that would allow a much sooner start to exploration and exploitation of the seabed areas on its side of the boundaries, in which the superjacent water column is the EEZ of one or other of these neighbours. In order to achieve this in those grey and doubly grey areas, however, a more co-operative approach will be needed than that which has hitherto been on display. Myanmar's 2015 amended submission has exacerbated the already existing problem, but if it remains unwilling to revise it, a selective modification by Bangladesh of its objection as suggested above can nonetheless neutralize it. Nor can Bangladesh resist such negotiation with its neighbours by pointing to the non-fulfilment by them of the condition of obtaining CLCS recommendations, as long as it is itself preventing that from happening by not withdrawing or at least modifying its objections that the Commission—albeit wrongly, in the author's view—treats as an obstacle to this.

After many years of uncritical acceptance of the flawed CLCS Rules of Procedure, several states are now voicing disquiet in annual meetings of the States Parties to UNCLOS about the indefinite blockage of their CLCS submissions by disputes.Footnote 88 The reports of the meetings, though, do not disclose any increasing trend in their number, which would have to increase substantially, forming a bloc with critical mass, for the CLCS to be persuaded to revisit that Annex. Any hope of exploiting the hydrocarbon resources of the affected area thus seems forlorn for the immediate future, and the plunge in international oil prices in 2020, followed by only a modest recovery, may have discredited for ever the “wine theory” alluded to in the introduction. Unless the littoral states are content to see these oil deposits become stranded assets in the medium term under an international energy dispensation geared towards combatting anthropogenic climate change, however, they may not have much time left to reverse their missteps.

POSTSCRIPT

In October 2020 Bangladesh amended its submission, replacing the original outer limit line based on paragraphs 4 and 5 of UNCLOS Article 76 with a new outer limit consisting solely of the parts of its boundaries with each of its neighbours running more than 200 nautical miles from its baseline.Footnote 89 This has not, however, necessitated any revision of the foregoing argumentation, as, in order to satisfy itself that Bangladesh's continental shelf entitlement extends at minimum as far these boundaries, the CLCS can still rely a fortiori on at least part of the information originally submitted by Bangladesh to show that there is in fact such an entitlement under paragraph 4. There is thus no need for Bangladesh to revise or update that information, nor indeed any indication in the executive summary that it has done so. The amendment does however mean that, if either Myanmar or India was considering objecting to examination by the CLCS of Bangladesh's submission as prejudicial to the now completed delimitations, there would no longer be any conceivable justification for this.