Defamation in Malaysia

Defamation, as a civil cause of action, is an umbrella term for the common law torts of libel and slanderFootnote 1 as augmented by the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia), which codifies certain defencesFootnote 2 and establishes certain privilegesFootnote 3, amongst other provisions. In essence, this cause of action involves the publication of an untrue imputationFootnote 4 to a third partyFootnote 5 that identifies the person impugned.Footnote 6 It is axiomatic that the imputation must be defamatory, which the courts have defined in a number of ways, such as whether the imputation would ‘tend to lower the plaintiff in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally’,Footnote 7 or ‘tends to make the plaintiff be shunned and avoided’,Footnote 8 or would ‘hold him up to contempt, scorn or ridicule or tend to exclude him from society’.Footnote 9 Indeed, in the case of Datuk Harris Mohd Salleh v Datuk Yong Teck Lee, the Federal Court succinctly explained that ‘[t]he tort of defamation exists to protect, not the person or the pocket, but reputation of the person defamed’.Footnote 10

In Malaysia, it has been suggested that defamation cases, in particular those involving online defamation, are on the rise,Footnote 11 to the extent that the courts are purportedly struggling to handle the sheer volume of cases filed in the High Court.Footnote 12 In the Kuala Lumpur High Court alone, it has been reported that the number of cyber-related tort cases filed, of which the majority were related to online defamation, has been rising year by year.Footnote 13 From approximately 50 cases in 2017, to approximately 60 cases in 2018; the most recent figures were closer to 70 cases in 2019.Footnote 14

The general increase in defamation cases has been attributed primarily to advances in technology, particularly with the increased accessibility to internet fora, messaging boards and social mediaFootnote 15 that can widely disseminate defamatory statements and can ‘publish or post a statement instantly that can reach thousands of people’.Footnote 16 Once published online, the content is ‘normally accessible for an indefinite period of time and can be easily repeated or republished in the cyber world’.Footnote 17 This can be true even if the statement has been deleted by the original uploader, as a result of re-blogging functions on certain social networking websites or web archiving services.

The issue of online libel is complicated by the fact that Malaysia has yet to abrogate the multiple publication rule. This rule finds its origins in the nineteenth century case of Duke of Brunswick v Harmer,Footnote 18 where the English courts held that each publication of a libel gives rise to a distinct and separate cause of action, with a correspondingly separate limitation period for each instance of publication. The multiple publication rule was first formulated, and was arguably more relevant, during an age of wet ink documents and scurrilous lampoons in privately-printed posters or pamphlets.Footnote 19 Notwithstanding, the rule was eventually adopted and applied to online publications in the English cases of Godfrey v Demon Internet Ltd Footnote 20 and Loutchansky v Times Newspapers Ltd,Footnote 21 as well as the Australian High Court case of Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick.Footnote 22 This meant that every time a new user accessed the webpage containing the defamatory content, it would constitute a new cause of action, effectively resetting the clock for the computation for any applicable limitation period. As such, for the purposes of establishing the date of publication and thus the accrual of the limitation period, ‘a post can be republished endlessly and exists until it is removed’Footnote 23 and would continue to attract liability ‘however long after the initial publication the material is accessed, and whether or not proceedings have already been brought in relation to the initial publication’.Footnote 24 Although England and Wales eventually abolished the multiple publication rule by way of statute,Footnote 25 the rule appears to still apply in MalaysiaFootnote 26 and would render online publishers ‘gravely exposed to unlimited liability’.Footnote 27

The number of cases may potentially rise even further after the Malaysian Federal Court ruled in the recent case of Chong Chieng Jen v Government of the State of Sarawak & Anor Footnote 28 (Chong Chieng Jen) that the Derbyshire Footnote 29 principle, which would ordinarily limit the right of public authorities to sue for defamation, did not apply to state governments in Malaysia. In its interpretation of the Government Proceedings Act 1956 (Malaysia),Footnote 30 the Malaysian apex court ruled that federal and state governments have the capacity to sue individuals for defamatory imputations. Carrying this ruling to the extreme, federal and state governments may theoretically sue each other for libellous statements. However, this has yet to be definitively tested in the Malaysian courts. It should be further noted that, close on the heels of the decision in Chong Chieng Jen, a municipal council has since initiated defamation proceedings against a member of the public.Footnote 31

Addressing the court's difficulty in handling such an enormous caseload of defamation claims, Hamid Sultan JC vented his grievances in the High Court case of Chew Peng Cheng v Anthony Teo Tiao Gin, where he stated that:

In many Commonwealth countries such as India and Malaysia, this tort has been statutorily codified, as a penal offence. Arguably it can be said that after it being codified courts should not have followed the common law remedy of defamation. Failing to do so, has promoted too many number of cases filed in a time and era where court has been inundated with much work … In fact, I will go to the extent of saying that time has come for Parliament to make defamation purely a criminal offence and make provisions for the criminal courts to order compensation, providing for a statutory maximum limit and/or alternatively to have all defamation matters heard before a magistrate or sessions judge, giving them the jurisdiction to hear and award damages to a defined maximum limit.Footnote 32

The learned Hamid Sultan JC elaborated on this observation in the subsequent High Court case of Dominica Toyat Dominic v Peter Wee Teck Ho, adding that ‘[i]t is time that Parliament amends the law for all defamation suits to be dealt with by criminal courts’.Footnote 33

Some of Hamid Sultan JC's recommendations were eventually passed by the legislature to holistically address the High Court's backlog of casesFootnote 34 by the enactment of the Subordinate Courts (Amendment) Act 2010 (Malaysia). This, amongst other provisions, increased the monetary jurisdiction of the Sessions Courts from RM 250,000 to RM 1,000,000Footnote 35 in addition to conferring the Sessions Courts with the power to grant injunctionsFootnote 36 and make declarations.Footnote 37 Crucially, however, the common law tort of defamation was not subsequently subsumed into a purely criminal offence as had been suggested, and neither the Malaysian Parliament nor the Malaysian Federal Court has made any discernible movement toward that end. This paper argues against denuding the tort of its civil status and proffers a different way of alleviating the Malaysian High Court's burden through alternative forms of dispute resolution.

The Case Against Criminal Defamation

Under Malaysian law, criminal defamation is an offence under section 499 of the Penal Code (Malaysia), which provides that:

Whoever, by words either spoken or intended to be read or by signs, or by visible representations, makes or publishes any imputation concerning any person, intending to harm, or knowing or having reason to believe that such imputation will harm the reputation of such person, is said, except in the cases hereinafter excepted, to defame that person.Footnote 38

This offence is punishable under section 500 of the Penal Code with imprisonment for a term up to two years, or a fine, or both.Footnote 39 The Malaysian High Court case of Pendakwa Raya v Ab Latif Muda is of some assistance where Amelia Tee Hong Geok Abdullah J listed out the ingredients as follows:

i. The imputation in question consisted of words, spoken or intended to be read, or of signs etc;

ii. The imputation concerned the complainant;

iii. Such imputation emanated from the accused;

iv. The accused made or published it; and

v. The accused intended thereby to harm the reputation of the complainant, or that he knew or had reason to believe that it would do so.Footnote 40

The problem identified in Chew Peng Cheng Footnote 41 and Dominica Toyat Dominic Footnote 42 warrants serious attention. Indeed, many modern civil defamation claims appear to be rather frivolous ventures,Footnote 43 oftentimes resulting from ‘the most ridiculous and strained interpretation of words which a person can conceive’,Footnote 44 which are filed at the expense of the Malaysian High Court's limited resources. However, the proposed solution to confine the resolution of defamation matters to the criminal jurisdiction would be an exceptionally unattractive and retrograde step which would likely offend the freedom of expression enshrined under Article 10(1)(a) of the Malaysian Federal Constitution.Footnote 45 After all, if every instance of proven defamation were to result in a criminal conviction, it is not difficult to anticipate a corresponding chilling effect on the right to freedom of expression,Footnote 46 especially in light of the fact that Hamid Sultan JC had opined that ‘the elements required to prove [criminal] defamation, have been made much easier in contrast to a civil action’.Footnote 47 Certainly, such a proposed legislative framework is likely to fail the ‘proportionality test’, laid down by the Malaysian Federal Court in Sivarasa Rasiah v Badan Peguam Malaysia & Anor,Footnote 48 to determine whether a given law is consistent with the Malaysian Federal Constitution.

In fact, the general trend around the globe appears to be towards applying a moratorium on criminal defamationFootnote 49 or abolishing it entirely,Footnote 50 instead of privileging it as the primary relief for reputational loss. In the House of Lords case of Gleaves v Deakin, Lord Diplock expressed his doubts over whether the offence of criminal defamation under the Libel Act 1843 (United Kingdom), in which the truth of the defamatory statement could only amount to a defence if it could be demonstrated that the publication of the libel was for the ‘public benefit’,Footnote 51 could comport with the right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights Footnote 52 (ECHR), stating that ‘Art[icle] 10 requires that freedom of expression shall be untrammelled by public authority except where its interference to repress a particular exercise of the freedom is necessary for the protection of the public interest.’Footnote 53

The Gleaves v Daekin judgment, amongst other findings, had been influential enough to galvanize British Parliament into enacting the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 (United Kingdom) which effectively decriminalized libel by virtue of sections 73Footnote 54 and 178Footnote 55 of that Act. However, whilst the ECHR does not appear to treat criminal defamation as a disproportionate violation of Article 10 of the ECHR in and of itself,Footnote 56 the imposition of a term of imprisonment – as is permitted under both section 5 of the Libel Act 1843 (United Kingdom) and section 500 of the Penal Code (Malaysia) – was held to be incompatible with the right to freedom of expression. The only exception was in rare cases where another fundamental human right had been seriously impaired.Footnote 57

Indeed, courts in other common law jurisdictions where criminal defamation had been codified have since declared the offence of criminal defamation to be unconstitutional. In Kenya, this can be seen in Jacqueline Okuta & another v Attorney General & 2 others;Footnote 58 in Zimbabwe, the case of Nevanji Madanhire & Anor v Attorney General;Footnote 59 and in Lesotho, the case of Basildon Peta v The Minister of Law, Constitutional Affairs and Human Rights & Ors.Footnote 60 One of the common jurisprudential threads interwoven through all three of these judgments was that civil defamation was appropriate and more than sufficient to protect reputational loss. The conclusions reached in these judgments are deeply compelling and cognisant of the chilling effect that criminal defamation laws may have on the right of freedom of expression. Admittedly, however, there are decisions in other jurisdictions where criminal defamation was held to be consistent with the relevant constitution, such as the Indian case of Subramanian Swamy v Union of India, Ministry of Law.Footnote 61 The Indian Supreme Court approached the issue by applying the doctrine of balancing fundamental rights. However, this Indian judgment has been subjected to criticismFootnote 62 and appears to not be aligned with the Indian Supreme Court's other recent determinations on the same issue of freedom of expression.Footnote 63

As a further consideration, by placing greater reliance on criminal defamation, there may be an unintended increase in defamation cases as, unlike civil defamation cases, section 499 of the Penal Code (Malaysia) allows for the dead to be defamed. However, concordant with Stephen J's judgment in R v Ensor, ‘a mere vilifying of the deceased is not enough … There must be a vilifying of the dead with a view to injure his posterity’.Footnote 64 In this regard, Explanation 1 of the offence under the Penal Code (Malaysia) states that: ‘It may amount to defamation to impute anything to a deceased person, if the imputation would harm the reputation of that person if living, and is intended to be hurtful to the feelings of his family or other near relatives.’Footnote 65 In PP v Mohamad Sabu, the Malaysian High Court held that historical events were justiciable in criminal defamation cases regarding deceased victims.Footnote 66 Therefore, this may also result in the court preferring one academic narrative on events which may have occurred in the distant past over others, which should not be the function of the courts.

Consistent with the rationes decidendi in Jacqueline Okuta, Nevanji Madanhire and Basildon Peta above,Footnote 67 the civil remedy is undoubtedly more suitable than criminal sanctions in addressing reputational loss. Indeed, legislating to abolish the tort of defamation in favour of the criminal offence under section 499 of the Penal Code (Malaysia) would be a superfluous solution to address an administrative problem when it could be sufficiently alleviated by a more measured method, as detailed in this paper. To that end, an alternative strategy involving introducing arbitration schemes is proposed which is postulated to have a similar outcome of reducing the caseload of the courts without the need to drastically restructure the existing statutory framework.

Are Defamation Claims Arbitrable Under Malaysian Law?

The primary benefits of arbitration over litigation for plaintiffs are ‘lower cost[s] and faster results’.Footnote 68 Additionally, arbitration of defamation claims may result in ‘awards that would not be available in a traditional trial, such as printing a retraction, or even giving the opposing party the chance to tell their side of the story’.Footnote 69 Separately, whilst the power to issue an injunction for an apology is available through the Malaysian legal system, the judicial attitudes are noticeably restrained in ordering this remedy, especially in cases where the defendant is recalcitrant and shows no remorse.Footnote 70 However, whilst the benefits of arbitrating media disputes cannot be overstated, a question arises over whether arbitration is a convenient and permissible method to resolve defamation claims under Malaysian law. The arbitrability of subject matter is addressed under section 4 of the Arbitration Act 2005 (Malaysia), which states that:

(1) Any dispute which the parties have agreed to submit to arbitration under an arbitration agreement may be determined by arbitration unless the arbitration agreement is contrary to public policy.

(2) The fact that any written law confers jurisdiction in respect of any matter on any court of law but does not refer to the determination of that matter by arbitration shall not, by itself, indicate that a dispute about that matter is not capable of determination by arbitration.

Traditionally, non-arbitrable subject-matter ‘would include criminal prosecutions, determination of status such as bankruptcy, divorce, and the winding up of corporations in insolvency, and certain types of dispute concerning intellectual property such as whether or not a patent or trademark should be granted. These matters are plainly for the public authorities of the state’.Footnote 71 Civil defamation does not fall under any of these categories and there does not appear to be any compelling reason as to why arbitration of defamation claims would be contrary to public policy. Even though defamation is a claim in tort, it is unlikely that this would represent an inherent bar to arbitrability as evinced by the fact that the Malaysian Court of Appeal has previously reviewed arbitral awards that made determinations on the tort of negligence without raising the tribunal's subject matter jurisdiction.Footnote 72

Incidentally, in the Malaysian High Court case of Daniel KC Tan & Associates Sdn Bhd v Progressive Insurance Sdn Bhd,Footnote 73 which involved proposed arbitration for a defamation matter, Kamalanathan Ratnam J did not specifically rule on the issue of arbitrability for a defamation claim. Although the plaintiff was eventually estopped from enforcing the arbitration clause as a result of approbating and reprobating, there was no suggestion from the learned judge that a defamation claim could not be arbitrated.

When examining persuasive common law authority in other jurisdictions, the issue of whether defamation claims are arbitrable appears to be largely settled.Footnote 74 In the English Court of Appeal case of Ecobank Transnational Incorporated v Tanoh,Footnote 75 Clarke LJ held that ‘there is … a high probability that the defamation claim falls within the [arbitration] clause’, indicating that defamation constitutes arbitrable subject matter under English law. In the New Zealand High Court case of Tamihere v Mediaworks Radio Ltd,Footnote 76 Simon France J was more direct in concluding that ‘a claim of defamation is capable of resolution through arbitration’.

In this regard, Nambuye J helpfully provided a four-step test to determine whether defamation fell within the arbitration clause in Achells Kenya Limited v Philips Medical Systems Nederland BV & Another:

[T]he ingredients that this court must look for … whether the defamation claim falls within the arbitration clause are:

(1) There must be an arbitration clause.

(2) It must be widely drafted.

(3) The defamation claim must be in relation to something done or not done arising from the contract.

(4) There must be a close connection between what is complained about and the contract.Footnote 77

The above test appears to comport with the broad latitude approach to construing arbitration clauses adopted in Malaysian cases such as Press Metal Sarawak v Etiqa Takaful Footnote 78 and the application of the Fiona Trust Footnote 79 principle. The general judicial position to allow arbitration insofar as the laws do not limit arbitrability was echoed in the judgment of T Selventhiranathan JCA in Albilt Resources v Casaris Construction where His Lordship held that:

The passing of the [Arbitration Act 2005] evinced Malaysia's intention and determination to join the ranks of those countries where parties are wont to submit differences or disputes to arbitration and the courts have to give effect to that postulation of the Legislature by interpreting the Act in accordance with the intention of the Legislature.Footnote 80

It is therefore highly likely that the Malaysian courts will hold that defamation claims are arbitrable in this jurisdiction, both as a matter of judicial attitude and even as a matter of public policy.

Lessons from The Leveson Report – Existing Arbitration Schemes

On 29 November 2012, the Leveson Report,Footnote 81 an exhaustive 2,000-page review into the culture, practice, and ethics of the British Press,Footnote 82 was published. Amongst its many recommendations, the one relevant to this paper is the provision of an arbitration service:

… the Board [of an independent self-regulatory body] should provide an arbitral process in relation to civil legal claims against subscribers, drawing on independent legal experts of high reputation and ability on a cost-only basis to the subscribing member … The process should be fair, quick and inexpensive, inquisitorial and free for complainants to use (save for a power to make an adverse order for the costs of the arbitrator if proceedings are frivolous or vexatious). The arbitrator must have the power to hold hearings where necessary but, equally, to dispense with them where it is not necessary. The process must have a system to allow frivolous or vexatious claims to be struck out at an early stage.Footnote 83

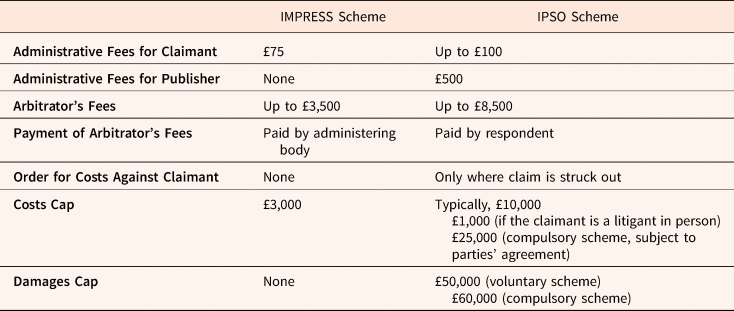

Following the recommendations of the Leveson Report, two arbitration schemes have since been established in the United Kingdom: the Independent Monitor for the Press (IMPRESS) Scheme and the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) Scheme. Although both schemes are fundamentally similar in the sense that they are designed for arbitration of media disputes involving their publisher members, including defamation claims, there are some crucial differences between them that this paper seeks to highlight.

The IMPRESS Scheme

The first of two media law arbitration schemes discussed in this paper is run by IMPRESS, described on its webpage as ‘a regulator designed for the future of media, building on the core principles of the past, protecting journalism, while innovating to deal with the challenges of a digital age’.Footnote 84 Their membership is made up of ‘more than 100 regulated publications’Footnote 85 (136 publications are listed as of 28 January 2020).Footnote 86

This arbitration scheme has been co-developed by both IMPRESS and the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb), who have jointly released a set of procedural rules called the CIArb/IMPRESS Arbitration Scheme Rules. These procedural rules limit the scope of this scheme to cover only civil claims by individuals or organisations against any of the publishers that are regulated by IMPRESS for defamation, breach of confidence, misuse of private information, malicious falsehood, harassment and breach of the Data Protection Act 2018 (United Kingdom).Footnote 87 Once a request for arbitration has been filed, IMPRESS makes an administrative assessment as to whether the dispute is suitable for arbitration under the IMPRESS Scheme.Footnote 88 If in the affirmative, the parties shall proceed to sign an arbitration agreement which is then submitted through IMPRESS to CIArb.Footnote 89 CIArb will then appoint an arbitrator from its panel who will determine the matter in accordance with rules.Footnote 90 The arbitration proceedings are expected to conclude within three months from the date of appointment of the arbitrator in cases where there is no oral hearing, and six months in all other cases.Footnote 91 This emphasis on expedient settlement is certainly attractive to complainants, especially when compared against defamation cases in the civil courts such as Gary Flood v Times Newspaper Footnote 92 (29 months) and Berezovsky v Russian Television and Radio Broadcasting Company and Terluk Footnote 93 (34 months). In McDonald's Corporation & McDonald's Restaurants Ltd v Steel and Morris,Footnote 94 the trial itself took 313 days, which at the time had been one of the longest trials in English legal history.Footnote 95 Indeed, according to an analysis made by Crossley of libel judgments between 2008 and the end of 2010, the average time from date of claim to date of final determination was just over 17 months.Footnote 96

The costs-saving provisions also make the IMPRESS Scheme rather attractive for potential litigants since IMPRESS is obligated to pay all the arbitrator's costs;Footnote 97 no order of costs can be made against the claimant, even if the claimant is the losing party or acts in a manner that would ordinarily attract adverse costs consequences.Footnote 98 However, whilst a claimant is shielded from an adverse costs order, the respondent is not. The IMPRESS Scheme allows for an order of costs to be made against the publisher for up to £3,000.Footnote 99 Indeed, other than a non-refundable filing fee of £75,Footnote 100 a claimant's financial exposure appears to be minimized.Footnote 101 One commentator candidly observed that: ‘[IMPRESS] caps arbitrators’ fees at £3,500 win or lose, and no legal costs if you win the case. The plaintiff can't lose financially; binding participation in arbitration is nil problem there. No wonder the local press don't like the sound of that’.Footnote 102

One rather peculiar aspect of the IMPRESS Scheme is that all awards are to be made public,Footnote 103 with the proviso that parties can apply to redact certain parts of the award in order to protect confidential information.Footnote 104 This is particularly interesting because, typically, arbitration proceedings and the award thereof are both private and confidential to the parties.Footnote 105 This is also reflected in the Malaysian jurisdiction by the recent additionFootnote 106 of section 41A(1) to the Arbitration Act 2005 (Malaysia).Footnote 107

Currently, there are two awards published by IMPRESS: Jonny Gould v Evolve Media Limited (Jonny Gould),Footnote 108 and Dennis Rice v Byline Media,Footnote 109, with at least three other live applications.Footnote 110 The need for vindication militates that the awards ought to be made public in order to provide adequate redress.Footnote 111 As a result, it is likely that a positive award under the IMPRESS Scheme that is accessible to the public would attain a far more attractive level of vindication compared to an anonymized judgmentFootnote 112 or a confidential damages settlement.Footnote 113

The IPSO Scheme

The other media arbitration scheme conducted in the United Kingdom is conducted by IPSO, the ‘independent regulator for the newspaper and magazine industry in the UK’;Footnote 114 it was created as a result of the Leveson Report.Footnote 115 Much like the IMPRESS Scheme, the IPSO Scheme covers claims relating to defamation, malicious falsehood, breach of confidence, misuse of private information, data protection, and harassment.Footnote 116 However, the IPSO Scheme differs insofar as it does not oblige subscription to the arbitration scheme by virtue of membership with the body. Instead, its members may choose one of the three following options:

(1) becomes members of the voluntary scheme, where requests to arbitrate may be made by complainants, but the publisher is not obliged to engage in the arbitral process;

(2) become a member of the compulsory scheme, whereby the publisher must accept any genuine arbitration claim; or

(3) not subscribe to either arbitration scheme.

Whilst this does preserve the autonomy of its members and emphasizes the voluntary nature of arbitration (as provided for in the Leveson Report),Footnote 117 it does limit the potential use of such a scheme. The options give the IPSO members broad discretion to reject arbitration as a method of resolution, even if it subscribes to the voluntary scheme.Footnote 118 To some degree, this defeats the purpose of the scheme as the media company would be able to dictate whether the potential claimant can proceed under the cost-saving scheme to vindicate their reputation. Indeed, with respect to the voluntary scheme, it was reported that‘[a]n IPSO member will therefore be able to deny low cost arbitration to an ordinary member of the public, knowing that s/he cannot afford to go to the High Court’Footnote 119 and that ‘[t]he regulator's existing arbitration scheme, which is not compulsory, allows publishers to essentially cherry pick the cases they agree to arbitrate.’Footnote 120 As a result of effectively delegating the decision to arbitrate with the publishers, IPSO ‘has not carried out any arbitrations under the voluntary scheme since it was established in 2016’,Footnote 121 and that ‘no cases were arbitrated in the time since the arbitration was first launched in 2016, an IPSO spokesperson told iMediaEthics’.Footnote 122

If a member does end up accepting the invitation to arbitrate, or is compelled to by virtue of its subscription to the compulsory scheme, the claimant must first undergo a referral stage in which the parties can consider early resolution of the dispute.Footnote 123 If the parties agree to proceed to arbitration, the respondent then provides a signed arbitration agreement to IPSOFootnote 124 and the dispute gets transferred to the Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution (CEDR) to appoint an arbitrator to preside over the matter.Footnote 125 The arbitrator is generally expected to complete the claim within 90 days of their appointment,Footnote 126 potentially twice the duration under the IMPRESS Scheme.

In contrast with the IMPRESS Scheme, which only involves a £75 filing fee paid by the claimant to initiate the proceedings,Footnote 127 the IPSO Scheme imposes an administrative fee of £500 for respondentsFootnote 128 and £100 for claimants to be paid in two tranches: the first £50 is to be paid prior to the appointment of an arbitrator, and the second £50 is to be paid upon a final ruling.Footnote 129 Typically, a cost order cannot be made against the claimant under the IPSO Scheme, even if the claimant is unsuccessful.Footnote 130 However, in the event the claim is struck out, the arbitrator may require the claimant to pay the respondent's costs.Footnote 131 This may only occur in four situations: where the claim is wholly unmeritorious, where the claim is trivial with the time and cost of pursuing the claim being wholly disproportionate to the potential award, where the claimant's conduct has frustrated the arbitration process and caused the respondent to incur unnecessary costs, and/or where the claim is otherwise frivolous or vexatious.Footnote 132 If the claim is struck out, the claimant may be subject to an order of costs up to £10,000, ratcheting down to £1,000 if the claimant is a litigant in person.Footnote 133 Under the compulsory scheme, the costs order can even be raised to £25,000, subject to parties’ agreement.Footnote 134 Whilst a potential cost order may act as a deterrent to claims that are vexatious, frivolous, or totally without merit,Footnote 135 the risk of being exposed to such costs, even after taking into account the lower limit in the case of a litigant in person, would be highly unattractive to a potential claimant, particularly if they are of limited means. This would also appear to depart somewhat from the Leveson Report's recommendation that any arbitration scheme should be ‘inexpensive … and free for complainants to use’.Footnote 136

Furthermore, rather than the arbitrator's fees being borne by the administering body, the IPSO Scheme obliges the respondent to pay.Footnote 137 However, whilst the arbitrator's fees for the IMPRESS Scheme is capped at £3,500 (absent any agreement to the contrary),Footnote 138 the arbitrator's fees under the IPSO Scheme can reach as high as £8,500 if the claim reaches a final ruling.Footnote 139 One commentator described this as such: ‘[IPSO] is rather loftier in its costings and more flexible in its obligations, but you know what, and who, you're getting.’Footnote 140

However, whilst the respondent under the IPSO Scheme is expected to pay an administrative fee and may be exposed to paying higher arbitrator's fees, it obtains the benefit of a damages cap of £50,000 under the voluntary schemeFootnote 141 or £60,000 under the compulsory scheme,Footnote 142 unless both parties agree to waive the damages cap.Footnote 143 Objectively, this damages cap is rather low, and this may deter potential claimants from engaging in the process, especially since the recommended limit for damages in defamation cases in the United Kingdom was held to be £275,000. This can be seen in the case of English Court of Appeal case of Cairns v Modi, where Lord Neuberger MR (as his Lordship then was) held that ‘[t]he present equivalent, allowing for inflation, and without taking account of any uplift consequential on what are usually described as the Jackson reforms taking effect in April 2013, would be of the order of £275,000’.Footnote 144

The reasoning behind the damages cap appears to be based on complainant demands, as Matt Tee, the chief executive of IPSO, elaborated: ‘[m]ost complainants are not seeking compensation, they just want the record set straight. They believe an article is inaccurate, discriminatory or otherwise in breach of the Editors’ Code of Practice. They usually want the story removed or corrected and an apology issued where appropriate.’Footnote 145 Arguably, however, the record is only properly set straight with a meaningful award for damages. This is in line with the principle that the ‘damages must be sufficient to demonstrate to the public that the plaintiff's reputation has been vindicated’Footnote 146 and that the claimant ‘must be able to point to a sum awarded by a jury sufficient to convince a bystander of the baselessness of the charge’.Footnote 147

A question then arises as to whether the IPSO Scheme's damages cap is sufficient to convince a bystander of the baselessness of the charge. According to the official statistics published by the United Kingdom's Ministry of Justice on 7 June 2018, of the 156 defamation cases filed in London in the year 2017, the value of the claim in 113 of those cases exceeded £50,000.Footnote 148 Indeed, a cap of £50,000 may be wholly insufficient to vindicate serious imputations such as false allegations of terrorismFootnote 149 or systematic sexual abuse.Footnote 150 An extreme example is the case of Garfoot v Walker, where a claimant falsely accused of rape was awarded a sum of £400,000 in damages.Footnote 151

In light of the preceding cases, this damages cap may potentially explain why complainants are hesitant to resolve their dispute under the IPSO Scheme since much higher awards are available under the traditional litigation framework. Damages caps generally favour the respondent at the expense of the bona fide claimant, who may be denied the full fruits of his claim despite being exposed to its risks and the certainty of legal fees. The new damages cap under the compulsory scheme introduced this year has been raised to £60,000,Footnote 152 but it remains to be seen if this cap is high enough to convince complainants to make use of the scheme.

Furthermore, unlike the IMPRESS Scheme, the awards issued by the arbitral tribunals under the IPSO Scheme are not necessarily made public. The decision to publish the final ruling via IPSO is at the discretion of the arbitrator.Footnote 153 Since ‘any confidential damages settlement will fail to vindicate the claimant's reputation’,Footnote 154 the exercise of any such power to keep the final ruling confidential may only be prudent in cases where the claimant is particularly vulnerable and the defamatory imputation against him is not revived in the public domain through the publication of the award. Such was the consideration before the Supreme Court of Canada case in AB v Bragg Communications Footnote 155 where the plaintiff was a fifteen-year-old girl who had been defamed. The Canadian Supreme Court allowed the plaintiff to proceed anonymously, chiefly on the grounds that there was ‘the right of children to protect themselves from bullying, cyber or otherwise’, that ‘young victims of sexualized bullying are particularly vulnerable to the harms of revictimization upon publication’, and that ‘the right to protection will disappear for most children without the further protection of anonymity’.Footnote 156 However, vulnerable claimants at risk of having the defamatory imputation revived by a public ruling are few and far between. When weighed against the necessity of vindication as an essential feature of redress for reputational loss, the decision to not make a ruling public should only be made under extraordinary circumstances. In any case, it remains to be seen how arbitrators would exercise their discretion to publish the final ruling or keep it confidential since there have been no reported arbitrations under the IPSO Scheme thus far (Table 1).

Table 1: Key differences between the IMPRESS Scheme and the IPSO Scheme

Could Similar Media Arbitration Schemes be Implemented in Malaysia?

Types of Claims

With reference to the list of arbitrable claims under the IMPRESS and IPSO Schemes, defamation,Footnote 157 malicious falsehoodFootnote 158 and breach of confidenceFootnote 159 are all recognized causes of action in the Malaysian jurisdiction. Whilst Malaysia does not have a statutory cause of action of harassment like the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 (United Kingdom),Footnote 160 the Malaysian Federal Court has imported the tort of harassment into Malaysian common law through the case of the Mohd Ridzwan Abdul Razak v Asmah Hj Mohd Nor.Footnote 161 Furthermore, although the Malaysian apex court has not confirmed the actionability of privacy-related torts, the Malaysian High Court has previously recognized the tort of misuse of private informationFootnote 162 as well as the tort of breach of privacy,Footnote 163 albeit the latter is somewhat more controversial.Footnote 164 However, there is currently no Malaysian equivalent to the civil claim for a statutory breach under the Data Protection Act 2018 (United Kingdom),Footnote 165 so disputes flowing from a breach of the Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (Malaysia) will remain under the competence of the criminal courts.Footnote 166 Nonetheless, the other aforementioned causes of action may be well-suited for dispute resolution under a Malaysian arbitration scheme similar to the IMPRESS or IPSO Schemes.

The Appointing Authority

Typically, where parties are unable to agree on an arbitrator, section 13 of the Arbitration Act 2005 (Malaysia)Footnote 167 empowers the Director of the Asian International Arbitration Centre (previously known as the Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration)Footnote 168 to make appointments upon application. The Asian International Arbitration Centre could be a potential candidate to act as the appointing authority, given the extensive and diverse panel of arbitrators availableFootnote 169 as well as the pre-existing machinery for carrying out the necessary appointment procedures. Alternatively, much like the IMPRESS Scheme which appoints arbitrators from the CIArb panel, Malaysia has its own local CIArb branch that could appoint arbitrators under a similar scheme. There are also several other reputable arbitration bodies based in this jurisdiction such as the Malaysian Institute of Arbitrators (MIArb) that could conceivably take on the role of empanelling a tribunal for the purposes of the scheme.

Recently, the Malaysian government has also established a pro tempore committee for a prospective Malaysian Media Council (MMC),Footnote 170 a ‘self-regulatory body that could set high standards for the media community to help build and maintain trust in the industry and act as an arbitration body between the public and the media in the interests of all Malaysians’.Footnote 171 Given the MMC's purported arbitral functions, this may present a timely opportunity for the MMC to curate and maintain their own panel of arbitrators with specialist knowledge of media law to resolve disputes involving those they regulate and aggrieved members of the public.

Damages Cap

While a damages cap would not be advisable for the same reasons traversed above in relation to the damages cap under the IPSO Scheme, on the other hand, such a mechanism may prove to be useful with respect to consistency and predictability, especially from the viewpoint of the media stakeholders and publishers that would be signed up to a potential scheme. Indeed, the inability to meaningfully or precisely quantify reputational loss has, on occasion, led to astronomically high awards against which teeter perilously on the brink of what would be punitive rather than restorative. In the English Court of Appeal case of Nail v News Group Newspapers Ltd, May LJ held that ‘the level of damages should not be so disproportionately high that freedom of expression is unduly curtailed’.Footnote 172 Similarly, the oft-cited European Court of Human Rights case of Tolstoy Miloslavsky v United Kingdom held that an excessively large award of £1,500,000 was so disproportionate to the defamatory statement that it impinged the right to freedom of expressionFootnote 173 under Article 10(1) of the ECHR. This has been acknowledged by the Malaysian Court of Appeal to be largely analogous to Article 10(1)(a) of the Malaysian Federal Constitution.Footnote 174

It seems clear that jurists in the common law world recognize the potential for defamation awards to unjustly oppress a defaming defendant, or inappropriately enrich a successful claimant. In the Malaysian jurisdiction, the perils of the latter reached its pinnacle in the case of MGG Pillai v Tan Sri Dato Vincent Tan Chee Yioun,Footnote 175 where the Malaysian Court of Appeal upheld a RM 10 million award for damages (which was subsequently affirmed by the Federal Court).Footnote 176 However, in the aftermath of such a judgment, the Malaysian courts appeared to have eschewed from awarding such crushing damages. Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as his Lordship then was), the same judge from the MGG Pillai case, observed in Liew Yew Tiam v Cheah Cheng Hoc that:

In the process of making our assessment we have not overlooked the recent trend in this country of claims and awards in defamation cases running into several million ringgit. No doubt that trend was set by the decision of this Court in MGG Pillai v Tan Sri Dato Vincent Tan Chee Yioun … we think the time has come when we should check the trend set by that case. This is to ensure that an action for defamation is not used as an engine of oppression. Otherwise, the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression will be rendered illusory.Footnote 177

This was echoed by a different quorum of the Malaysian Court of Appeal in Harry Isaacs & Ors v Berita Harian Sdn Bhd & Ors, where Anantham Kasinather JCA held that:

In our judgment, the award of a sum running into millions of dollars in the case of MGG Pillai v Tan Sri Dato Vincent Tan Chee Yioun was made during a period of unrestrained excesses by the judiciary and consequently not one which we are inclined to follow.Footnote 178

However, despite the brakes imposed by the Malaysian Court of Appeal,Footnote 179 the Malaysian first instance courts below have not demonstrated universal restraint when awarding damages, with recent cases still running into the millions such as the case of Nurul Izzah binti Anwar v Tan Sri Khalid bin Abu Bakar & Anor Footnote 180 where Faizah Jamaludin JC (as Her Ladyship then was) awarded RM 1 million in damages. In Melawangi Sdn Bhd v Yeo Ing King, an award of RM 5 million was made,Footnote 181 although the court rationalized awarding the extravagant quantum of damages on the basis that that the defendant in that case never challenged the wholly exorbitant claim. Azimah Omar JC (as he Her Ladyship then was) stated that ‘having no benefit of the Defendant's contention, challenge and evidence of quantum, the Court is left with no alternative but to allow the Plaintiff's claim to its full extent’.Footnote 182 These recent judgments appear to run entirely against the grain of the Malaysian Court of Appeal's pronouncements that such exorbitant damages are reflective of a bygone age of ‘unrestrained excesses by the judiciary’.Footnote 183 If the aforementioned cases are of any indication, unrestrained excesses are likely to continue unabated. As such, if the public perception is that it is entirely possible to recover millions in damages for a defamation claim, as evinced by astronomical claims in damages,Footnote 184 a damages cap for any potential arbitration scheme, whilst effectively introducing a hard stop on extreme fluctuations in awards, may also drastically deter plaintiff participation if the threshold is too modest.

Notwithstanding, the Malaysian Court of Appeal has continued to reiterate its position on excessive damages for defamation. In the Malaysian Court of Appeal case of Syed Nadri Syed Harun & Anor v Lim Guan Eng and other appeals (Syed Nadri Syed Harun), the plaintiff was awarded RM 550,000 in damages by the Malaysian High Court for an imputation of that the plaintiff had compromised his loyalty to Malaysia.Footnote 185 The plaintiff cross-appealed on the quantum on the basis that the damages awarded were too low after taking into account the plaintiff's status as an elected Member of Parliament, an elected member of the Penang State Assembly, as well as the Chief Minister of Penang.Footnote 186 The Malaysian Court of Appeal dismissed the plaintiff's cross-appeal and reduced the award of damages to RM 150,000, stating that ‘[t]he days of million Ringgit award for defamation has long gone and consigned to history’Footnote 187 and that award was ‘excessive and not in line with the trend of cases’.Footnote 188

Typically, to determine the quantum of damages for defamation, the court is obliged to consider the conduct of the plaintiff, the plaintiff's position and standing in society, the nature of the libel, the mode and extent of publication, the absence or refusal of a retraction or apology and the whole conduct of the defendant from the time the libel was published down to the very moment of the verdict.Footnote 189 However, it had entered judicial reasoning to compare reputational loss with physical injury as a method of determining the reasonableness of the quantum. In the English Court of Appeal case of John v MGN Ltd, Lord Bingham MR held that:

It is in our view offensive to public opinion, and rightly so, that a defamation plaintiff should recover damages for injury to reputation greater, perhaps by a significant factor, than if that same plaintiff had been rendered a helpless cripple or an insensate vegetable.Footnote 190

This view was echoed in the English Court of Appeal case of Jones v Pollard, where Hirst LJ stated that ‘save possible in the most exceptional case, I find it difficult to imagine any defamation action where even the most severe damage to reputation, accompanied by maximum aggravation, would be comparable to such appalling physical injuries [such as quadriplegia]’.Footnote 191

The Malaysian courts have curiously held that the quantum for defamation claims ought to not be compared with awards for physical injury.Footnote 192 However, there have been judgments where a putative threshold for damages was canvassed. In the Malaysian High Court case of Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim v The New Straits Times Press (M) Sdn Bhd & Anor, in a similar vein to Hirst LJ's view in Jones v Pollard, Harmindar Singh Dhaliwal JC (as his Lordship then was) (Harmindar Singh JC) held that ‘[e]ven in the most serious cases of defamation in respect of integrity and honour, I cannot imagine general damages to exceed the quantum that is usually awarded in personal injury claims to a claimant who is fully disabled’.Footnote 193 The learned Harmindar Singh JC explained that ‘a man who has been defamed cannot be said to be in a worse position than one who has lost the use of vital parts of his or her anatomy’,Footnote 194 citing the case of McCarey v Associated Newspapers Ltd (No 2). Footnote 195

Whilst it is true that damages for defamation are typically ‘at large’Footnote 196 and ‘[t]he amount to be awarded in each case depends on the facts and circumstances of the case’,Footnote 197 the quantum of damages in personal injury cases is no better a bellwether for the appropriateness of damages to be awarded for defamation. This especially since the ‘[l]oss of life and limb are equally serious and in terms of hierarchy should be placed on the same level as defamation suits’.Footnote 198 It should be stressed that the comparison with damages in personal injury would not be for the purposes of computing the actual quantum, but rather to act as ‘as a check on the reasonableness of a proposed award of damages for defamation’.Footnote 199

Naturally, for a comparison to be relevant to defamation awards in the Malaysian jurisdiction, such an exercise will need to be carried out against awards for personal injury in Malaysia to determine the reasonableness of an award.Footnote 200 Indeed, by assessing personal injury cases involving quadriplegia, which was one of the medical conditions identified by Hirst LJFootnote 201 and alluded to by Harmindar Singh JC,Footnote 202 it can be observed that this figure is, in actuality, much more conservative than the RM 10 million in damages upheld in MGG Pillai.Footnote 203

In Marappan v Siti Rahmah bte Ibrahim,Footnote 204 the Malaysian Supreme Court upheld an assessment of RM 180,000 as general damages for pain, suffering, and loss of amenities as a result of the complete paralysis in all four limbs. Similarly, in Wong Fook v Abdul Shukur bin Abdul Halim (Wong Piang Loy, Third Party),Footnote 205 the Malaysian High Court awarded RM 180,000 in general damages for quadriplegia. However, as these cases were decided several decades ago, they would naturally have to be adjusted for inflation, which in today's currency would be closer to RM 400,000.Footnote 206 This is supported by the Revised Compendium of Personal Injury Awards,Footnote 207 which provides that the award for the quadriplegia should be between RM 300,000 to 420,000.Footnote 208

If a cap for damages is necessary for a media arbitration scheme to operate in Malaysia, a RM 300,000 limit for damages would present a workable figure. This is because it falls comfortably short of the maximum amount which could be awarded for the most debilitating lifelong physical injury. At same time, the amount is not so derisory that plaintiffs may be deterred from pursuing a claim through arbitration. Indeed, the appropriateness of this figure is buttressed by Syed Nadri Syed Harun, where the Malaysian Court of Appeal identified three awards of RM 300,000,Footnote 209 RM 150,000,Footnote 210 and RM 200,000Footnote 211 to exemplify the ‘trend of damages awarded by the court in a suit of defamation’.Footnote 212 Of course, any Malaysian media arbitration scheme's rules framework should also allow for appropriate mechanisms that enable the relevant appointing authority or scheme's organizer to amend the cap from time to time to take into account variables such as inflation.

Defences under the Defamation Act 1957

There is some uncertainty whether the defences codified in the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia) would be available to claimants under the Malaysian arbitration scheme. This is because the applicability of these defences is specifically with respect to an ‘action for libel or slander’.Footnote 213 The word ‘action’ is defined under the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (Malaysia) as ‘a civil proceeding commenced by writ or in such other manner as is prescribed by rules of court, but does not include a criminal proceeding’.Footnote 214 Crucially, however, arbitral proceedings do not appear to fall within the ambit of ‘action’ under this definition.

Indeed, the Limitation Act 1953 (Malaysia) acknowledges ‘arbitrations’ to be an entirely separate species from ‘actions’, stating that ‘[the Limitation Act 1953] and any other written law relating to the limitation of actions shall apply to arbitrations as they apply to actions’.Footnote 215 As such, since the law appears to distinguish ‘arbitrations’ from ‘actions’, on a strict interpretation of the word ‘action’ under the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia), these defences would seemingly not apply to a defamation claim being resolved by way of arbitration.

Nonetheless, this does not represent a significant hurdle to overcome. Firstly, many of these codified defences have already been bred in the bone of the common law, which has been given the force of law under the Civil Law Act 1956 (Malaysia).Footnote 216 The apparent concurrency of the statutory and common law defences has been alluded to by the courts on several occasions. For example, in the case of Dato Sri Dr Mohamad Salleh bin Ismail & Anor v Nurul Izzah bt Anwar & Anor,Footnote 217 the Malaysian Court of Appeal explained that justification was a complete defence, both ‘at common law, as well as under our very own statutory regime’. In Dato Dr Tan Chee Khuan, the Malaysian High Court described the defence of fair comment, whether ‘pursuant to s 9 of the Defamation Act 1957 or the common law’.Footnote 218 Furthermore, unlike its current counterpart in the United Kingdom, the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia) does not purport to abolish any of the common law defences.Footnote 219 As such, even if the defences under the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia) were not available, respondents could theoretically still rely on the common law defences to defamation.

Notwithstanding the literal meaning of ‘action’, it is likely that an arbitral tribunal will still refer to the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia) for guidance. Indeed, the Defamation Act 1952 (United Kingdom) also contain provisions that apply to an ‘action’ for libel and slander,Footnote 220 which has been defined by the Senior Courts Act 1981 (United Kingdom) as ‘any civil proceedings commenced by writ or in any other manner prescribed by rules of court’,Footnote 221 similarly excluding arbitral proceedings from that definition. Despite this, the arbitral tribunal in Jonny Gould Footnote 222 still took cognisance of section 12 of the Defamation Act 1952 (United Kingdom), notwithstanding that the section applies to an ‘action’ for libel or slander. Admittedly, this was only one case; it remains to be seen whether future tribunals will follow this approach. However, given that the purpose of the media arbitration scheme is to be an alternative to litigation, it would be perverse if the respondent could not avail itself to the same defences as it would have had in a court of law. As such, as in Jonny Gould, it is expected that Malaysian tribunals will similarly apply the local defamation statutes to any arbitral proceedings for defamation.

In any case, as arbitration is a creature of contract,Footnote 223 the parties would have the ability to apply or disapply the Defamation Act 1957 (Malaysia) through an arbitration agreement. As such, a term applying the relevant statute should be included into the pro forma arbitration agreement under any Malaysian media arbitration scheme, or alternatively, the available defences should be listed in the applicable media arbitration rules, in which the parties would have agreed to apply in the pro forma agreement.

Conclusion

The issues identified by the Hamid Sultan JC are certainly worth addressing. However, the alleviation of the courts’ heavy caseload of defamation claims should be by way of alternative dispute resolution such as arbitration, instead of legislative reform to convert the tort of defamation into a purely criminal offence. Indeed, given that criminal prosecutions are likely to fall outside the ambit of arbitrability under section 4 of the Arbitration Act 2005 (Malaysia),Footnote 224 subsuming civil defamation into the offence of criminal defamation would effectively render it non-arbitrable; the two solutions are diametrically-opposed to each other.

On the basis that publisher adoption is actively encouraged and managed, whether through the nascent MMC or otherwise, a media arbitration scheme has the potential to significantly reduce the number of defamation cases appearing before the civil courts in Malaysia. However, for it to be attractive to parties, in particular the complainants, it is imperative that any scheme adheres closely to the recommendations in the Leveson Report: an arbitration scheme should be ‘fair, quick and inexpensive, inquisitorial and free for complainants to use’.Footnote 225 If there is sufficient stakeholder motivation, there would certainly be enough local players and arbitrators to make such a scheme a viable and popular alternative to traditional litigation in Malaysia, thereby obviating the need to inundate the court with defamation claims.

Author Biography

Imaduddin Suhaimi, Fellow, Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb); Fellow, Malaysian Institute of Arbitrators (MIArb); Panel Member, Asian International Arbitration Centre (AIAC); Panel Member, Brunei Darussalam Arbitration Centre; LLB, LLM, BSc (Biology), MSc (Molecular Biology), ARCS, FMIArb, FCIArb, DipIArb, Advocate and Solicitor (High Court of Malaya).