Skilled readers can easily identify printed words in a variety of formats (e.g., animal, animal, ![]() ; see Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby, & Clifton, Reference Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby and Clifton2012, for review). To explain the resilience of the cognitive system to the changes in the visual appearance of words, most models of written word recognition assume that the visual features of each of the word’s component letters (e.g., curvatures, lines, terminals, junctions, etc.) are gradually mapped onto an array of abstract letter detectors (e.g., the detector for “G” would respond similarly to g,

; see Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby, & Clifton, Reference Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby and Clifton2012, for review). To explain the resilience of the cognitive system to the changes in the visual appearance of words, most models of written word recognition assume that the visual features of each of the word’s component letters (e.g., curvatures, lines, terminals, junctions, etc.) are gradually mapped onto an array of abstract letter detectors (e.g., the detector for “G” would respond similarly to g, ![]() , G, and

, G, and ![]() ; see Dehaene, Cohen, Sigman, & Vinckier, Reference Dehaene, Cohen, Sigman and Vinckier2005; Grainger, Rey, & Dufau, Reference Grainger, Rey and Dufau2008, for neurally inspired models; see also Grainger, Dufau, & Ziegler, Reference Grainger, Dufau and Ziegler2016, for a recent review). These abstract letter detectors would be the impelling force behind lexical access (see Bowers, Vigliocco, & Haan, Reference Bowers, Vigliocco and Haan1998; Jacobs, Grainger, & Ferrand, Reference Jacobs, Grainger and Ferrand1995, for early empirical evidence with the masked priming technique [Forster & Davis, Reference Forster and Davis1984]).

; see Dehaene, Cohen, Sigman, & Vinckier, Reference Dehaene, Cohen, Sigman and Vinckier2005; Grainger, Rey, & Dufau, Reference Grainger, Rey and Dufau2008, for neurally inspired models; see also Grainger, Dufau, & Ziegler, Reference Grainger, Dufau and Ziegler2016, for a recent review). These abstract letter detectors would be the impelling force behind lexical access (see Bowers, Vigliocco, & Haan, Reference Bowers, Vigliocco and Haan1998; Jacobs, Grainger, & Ferrand, Reference Jacobs, Grainger and Ferrand1995, for early empirical evidence with the masked priming technique [Forster & Davis, Reference Forster and Davis1984]).

A much less studied topic is whether the activation of these abstract letter detectors is modulated by visual similarity in the initial moments of word processing. As acknowledged by Davis (Reference Davis2010), the implemented version of most computational models of visual word recognition use a rudimentary scheme between the “feature” and “letter” levels (Rumelhart & Siple’s, Reference Rumelhart and Siple1974, font), the reasons being that (a) the main focus of these models was the “word” level; and (b) one needs to know what are the key phenomena to simulate in the “feature” and “letter” levels (see Rosa, Perea, & Enneson, Reference Rosa, Perea and Enneson2016, for discussion). A plausible assumption is that, as occurs with the encoding of letter order (see Massol, Duñabeitia, Carreiras, & Grainger, Reference Massol, Duñabeitia, Carreiras and Grainger2013), there is some perceptual uncertainty at encoding abstract letter identities in the initial moments of word processing (Bayesian reader model: Norris & Kinoshita, Reference Norris and Kinoshita2012). Previous research has shown that abstract letter detectors are resilient to variations in the printed form of the stimuli: degraded stimuli (e.g., ![]() ) or stimuli created with letter-like digits (e.g., M4T3RIAL) are very effective as masked primes (see Hannagan, Ktori, Chanceaux, & Grainger, Reference Hannagan, Ktori, Chanceaux and Grainger2012; Molinaro, Duñabeitia, Marín-Gutiérrez, & Carreiras, Reference Molinaro, Duñabeitia, Marín-Gutiérrez and Carreiras2010; Perea, Duñabeitia, & Carreiras, Reference Perea, Duñabeitia and Carreiras2008).

) or stimuli created with letter-like digits (e.g., M4T3RIAL) are very effective as masked primes (see Hannagan, Ktori, Chanceaux, & Grainger, Reference Hannagan, Ktori, Chanceaux and Grainger2012; Molinaro, Duñabeitia, Marín-Gutiérrez, & Carreiras, Reference Molinaro, Duñabeitia, Marín-Gutiérrez and Carreiras2010; Perea, Duñabeitia, & Carreiras, Reference Perea, Duñabeitia and Carreiras2008).

Critically, there is empirical evidence of visual similarity effects in Latin-based orthographies: a target word like DENTIST is responded to faster when briefly preceded by a visually similar substituted-letter prime (dentjst; note that i and j are rated as visually very similar [5.12 of 7] in the Simpson, Mousikou, Montoya, & Defior, Reference Simpson, Mousikou, Montoya and Defior2012, norms) than when preceded by a visually dissimilar substituted-letter prime (dentgst; Kinoshita, Robidoux, Mills, & Norris, Reference Kinoshita, Robidoux, Mills and Norris2013; Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018a; see also Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2018b, for evidence with the boundary technique during sentence reading). To examine in detail the time course of the effects of visual similarity during word recognition, Gutiérrez-Sigut, Marcet, and Perea (Reference Gutiérrez-Sigut, Marcet and Perea2019) conducted two masked priming lexical decision experiments using the stimuli from Marcet and Perea (Reference Marcet and Perea2017) while recording event-related potentials (ERPs). They found that the identity condition (e.g., dentist-DENTIST) and the visually similar condition (dentjst-DENTIST) produced similar ERP waves in a component related to the orthographic overlap between prime and target (N250; see Grainger & Holcomb, Reference Grainger and Holcomb2009, for a review of the ERP literature in word recognition), whereas the visually dissimilar condition (e.g., dentgst-DENTIST) produced larger amplitudes. Later in processing, when measuring a component related to lexicosemantic activation (N400), the amplitudes were larger in the visually similar and visually dissimilar conditions than in the identity condition. Taken together, these findings suggest that there is some uncertainty at encoding letter identity during word processing that is finally resolved.

In contrast, the effects of visual similarity do not seem to occur in Arabic. Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa, and Carreiras (Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) found that word identification times for a target word like ![]() (SHfyp with the Buckwalter transliteration [journalist in English]) are remarkably similar when preceded by a visually similar replaced-consonant prime that only differed in the diacritical sign of the critical letter (e.g.,

(SHfyp with the Buckwalter transliteration [journalist in English]) are remarkably similar when preceded by a visually similar replaced-consonant prime that only differed in the diacritical sign of the critical letter (e.g., ![]() Sxfyp; compare

Sxfyp; compare ![]() and

and ![]() and when preceded by a visually dissimilar replaced-consonant prime (e.g.,

and when preceded by a visually dissimilar replaced-consonant prime (e.g., ![]() Skfyp)—this was accompanied by a substantial advantage of the identity condition over the visually similar condition. Perea et al. suggested that the lack of visual similarity effects in Arabic was due to the fundamental importance of these signs in Arabic: most consonant letters only differ by the number and/or position of these signs (e.g.,

Skfyp)—this was accompanied by a substantial advantage of the identity condition over the visually similar condition. Perea et al. suggested that the lack of visual similarity effects in Arabic was due to the fundamental importance of these signs in Arabic: most consonant letters only differ by the number and/or position of these signs (e.g., ![]() etc.).Footnote 1

etc.).Footnote 1

The dissociation of visual similarity effects in the Latin and Arabic scripts may be taken to suggest that there may be qualitative differences in letter/word processing in these scripts. Wiley, Wilson, and Rapp (Reference Wiley, Wilson and Rapp2016) found that diacritical signs are the most important feature when processing isolated letters in Arabic. Another explanation is that there is something special with the processing of letters with diacritics regardless of script. Although diacritical signs are absent in modern English, they are the norm rather than the exception in the vast majority of European languages (e.g., ñ, č, š, ž, ř, ċ, ġ, ż, ć, š, ž, ç, ķ, ļ, ņ, ŗ, ș, ț, etc.). Furthermore, diacritics are also employed in other scripts (e.g., Thai, Hebrew, Greek, Sanskrit, and Japanese kana). However, given that most current models of word recognition focus on letter/word processing in English (see Share, Reference Share2008, for discussion), they are agnostic as to the similarities/differences in processing between letters with/without diacritical signs.

There is some recent evidence that supports the idea that diacritics have a special role in letter/word processing in the Latin script. In a recent masked priming lexical decision experiment in French, Chetail and Boursain (Reference Chetail and Boursain2019) found a substantial 50-ms advantage of the identity condition (e.g., taper-TAPER) over a visually similar replaced-vowel priming condition in which the vowel had a diacritical sign (tâper-TAPER). Furthermore, the latencies of the visually similar priming condition (tâper-TAPER) were similar as the latencies of a visually different replaced-vowel priming condition (tuper-TAPER). Chetail and Boursain also found a similar pattern when using a masked priming alphabetic decision task with isolated letters (i.e., a-A < â-A = z-A). Likewise, in masked priming lexical decision, Domínguez and Cuetos (Reference Domínguez and Cuetos2018) reported this same pattern with Spanish words (rasgo-RASGO < rasgó-RASGO = persa-RASGO). Taken together, these experiments suggest not only that participants can rapidly encode diacritical signs from vowels in the Latin script but also that they treat these vowels with diacritical signs as completely separate letters from the original vowels (i.e., the letter â does not seem to activate the unit corresponding to the letter a).

However, there is an interpretative issue when comparing the effects of visual similarity obtained with the Arabic versus Latin scripts in the above-cited experiments: the experiments in Arabic manipulated visual similarity in consonants, whereas the experiments in Latin-based orthographies manipulated visual similarity in vowels. There is ample consensus in the literature of word recognition and reading that consonants and vowels are processed differently (see Caramazza, Chialant, Capasso, & Miceli, Reference Caramazza, Chialant, Capasso and Miceli2000, for neuropychological evidence; see Carreiras, Gillon-Dowens, Vergara, & Perea, Reference Carreiras, Gillon-Dowens, Vergara and Perea2009, for electrophysiological evidence; see Carreiras & Price, Reference Carreiras and Price2008, for fMRI evidence). Furthermore, a large body of evidence has shown that consonants may be more important than vowels when accessing the mental lexicon (see Berent & Perfetti, Reference Berent and Perfetti1995, for a model; see New, Araújo, & Nazzi, Reference New, Araujo and Nazzi2008, for behavioral evidence).

The main goal of the current masked priming experiment was to examine whether visual similarity effects arise when using consonants with versus without diacritical signs in Latin script (e.g., moñeda-MONEDA vs. moseda-MONEDA [moneda is the English for coin]). Thus, this is the same scenario as in the Perea et al. (Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) experiments with Arabic letters. Although consonants with diacritical signs are absent in modern English, they are the norm rather than the exception in the vast majority of European languages (e.g., ñ, č, š, ž, ř, ċ, ġ, ż, ć, š, ž, ç, ķ, ļ, ņ, ŗ, ș, and ț) as well as in many other scripts (e.g., Thai, Hebrew, Greek, Sanskrit, and Japanese kana). In the current paper, we focused on Spanish orthography. Spanish has two consonant letters that share the basic shape and only differ in the presence/absence o fa diacritical sign: n (pronounced as /n/) and ñ (pronounced as ![]() )—note that the letter “ñ” is the only consonant with diacritical signs in Spanish. These two letters are rated as more visually similar (6.27 out of 7 in the Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Mousikou, Montoya and Defior2012, norms) than the letters employed in previous experiments in the Latin script (e.g., i/j: 5.12 of 7; u/v: 4.93 of 7, in the Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018b, experiments). The diacritical signs in Spanish must be written in both formal and informal contexts—note that the letter ñ has its own key in computer keyboards sold in Spanish-speaking countries.

)—note that the letter “ñ” is the only consonant with diacritical signs in Spanish. These two letters are rated as more visually similar (6.27 out of 7 in the Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Mousikou, Montoya and Defior2012, norms) than the letters employed in previous experiments in the Latin script (e.g., i/j: 5.12 of 7; u/v: 4.93 of 7, in the Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018b, experiments). The diacritical signs in Spanish must be written in both formal and informal contexts—note that the letter ñ has its own key in computer keyboards sold in Spanish-speaking countries.

A second goal of the experiment is to examine whether the effects of visual similarity when processing words containing letters with a diacritical sign are bidirectional or not. Previous masked priming experiments using visually similar letters in the Latin alphabet found a similar pattern regardless of the frequency of the letters (Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018b): the effects were equivalent in size from i to j (e.g., pasaiero-PASAJERO = pasajero-PASAJERO [PASSENGER]) and from j to i (e.g., dentjst-DENTIST = dentist-DENTIST) despite the fact that the letter i is considerably more frequent than the letter j in Spanish (6.2% vs. 0.5% per million). However, this bidirectional pattern may not be generalized to diacritical letters. A prime containing the letter n would be a good match for the letter ñ (i.e., it contains the same basic letter shape), so it may be initially confusable with its counterpart ñ, thus producing a visual similarity effect (e.g., jalapeno would activate the entry corresponding to JALAPEÑO). However, the diacritical sign ~ is a highly salient element so that a prime containing this sign on top of the glyph n might not be highly effective (keep mind that the diacritical sign ~ would exclude the letter “n” as a good match). This question was not examined in the Chetail and Boursain (Reference Chetail and Boursain2019) and Domínguez and Cuetos (Reference Domínguez and Cuetos2018) experiments: they always used stimuli with diacritical signs as primes (e.g., tâper-TAPER, but not decider-DÉCIDER).

In sum, we designed a masked priming lexical decision experiment to examine the role of diacritical signs on consonants in the initial moments of word processing in a Latin-based orthography (Spanish). We included three prime-target conditions: (a) a visually similar condition in which we replaced the letter n/ñ with its counterpart (SIM condition; e.g., moñeda-MONEDA; muneca-MUÑECA [moneda and muñeca are the Spanish for coin and doll, respectively]); (b) a visually dissimilar condition in which we replaced the letter n/ñ with a visually dissimilar letter (DIS condition; e.g., moseda-MONEDA; museca-MUÑECA); and (c) an identity condition (ID condition; e.g., moneda-MONEDA; muñeca-MUÑECA), which allowed us to estimate the degree of effectiveness of the visually similar priming condition. Primes and targets were presented in different cases (from lowercase to uppercase) to avoid physical continuity, thus ensuring a more abstract processing of the stimuli (see Forster, Mohan, & Hector, Reference Forster, Mohan, Hector, Kinoshita and Lupker2003, for discussion). As in previous research, the two critical comparison were between the visually similar condition and the visually dissimilar condition (SIM vs. DIS) and between the identity condition and the visually similar condition (ID vs. SIM; see Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017; Perea et al., Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018, for discussion).

If consonant letters that share the basic shape (e.g., n and ñ) were initially processed as other visually similar letters in the Latin script (e.g., i-j, u-v; see Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018a), target words like MONEDA would produce faster word identification times when preceded by a visually similar prime (e.g., moñeda) than when preceded by a visually dissimilar prime (e.g., moseda). Furthermore, the visually similar condition might be as effective as the identity condition (i.e., SIM < DIS and ID ≤ SIM). This pattern would generalize the visual similarity effects obtained by Marcet and Perea (Reference Marcet and Perea2017; see also Gutiérrez-Sigut et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Sigut, Marcet and Perea2019) to letters with diacritical signs (n/ñ), thus suggesting a qualitative difference between the processing of consonants with diacritics in Arabic and Latin-based scripts. However, if diacritical consonants and their counterparts activate completely separate abstract letter representations in the initial moments of processing (i.e., n would not activate ñ more than a control letter; ñ would not activate n more than a control letter), one would expect no visual similarity effects (i.e., SIM = DIS and ID < SIM). This pattern would resemble the findings in the Arabic script (see Perea et al., Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) and it would suggest that, regardless of script, diacritics play a major role in the initial moments of word processing. Finally, there is an intermediate scenario: one might argue that only the letters with diacritical signs play a special role during the initial stages of processing (i.e., n would activate ñ, whereas ñ would not activate n more than a control letter; see above). If so, one would expect a different pattern for moneda-type words and muñeca-type words: word identification times would be similar for moñeda-MONEDA and moseda-MONEDA (i.e., a pattern similar to that reported by Chetail & Boursain, Reference Chetail and Boursain2019, and Perea et al., Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018, using primes in which the critical letters contained diacritical signs), but word identification times would be faster for muneca-MUÑECA than for museca-MUÑECA (i.e., a visual similarity effect; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Sigut, Marcet and Perea2019; Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, using primes in which the critical letters did not contain diacritical signs).

Method

Participants

Forty-two undergraduate students of a public university in Spain participated voluntarily in the experiment. With this sample size, the number of observations in each priming condition was 1,848, which is above the recommendations of Brysbaert and Stevens (Reference Brysbaert and Stevens2018). All participants were native of Spanish with no problems of vision or reading. They signed a consent informed form before the experiment.

Materials

We selected 132 Spanish words from the subtitle database of the EsPal database (Duchon, Perea, Sebastián-Gallés, Martí, & Carreiras, Reference Duchon, Perea, Sebastián-Gallés, Martí and Carreiras2013). Half of them contained the letter ñ in an internal position (muñeca-type words) and the other half contained the letter n in an internal position (moneda-type words)—note that the letter n/ñ was always between two vowels. These two types of words were matched in Zipf frequency, number of letters, and orthographic neighborhood (OLD20; all ps > .35). For the muñeca-type words, the average Zipf frequency (log10[frequency per million]+3 in EsPal) was 3.9 (range: 2.5–5.6), the average number of letters was 6.9 (range: 5–10), and the average OLD20 was 2.0 operations (range: 1.0–3.5), whereas for the moneda-type words, the average Zipf frequency was 3.9 (range: 2.3–5.8), the average number of letters was 6.9 (range: 5–10), and the average OLD20 was 2.0 operations (range: 1.2–3.3). Each target word was preceded by a prime that could be: (a) identical to the target word (identity [ID] condition: muñeca-MUÑECA; moneda-MONEDA); (b) the same as the target word except that the letter “n” was replaced with “ñ” or vice versa, creating a pseudoword (visually similar [SIM] condition: muneca-MUÑECA; moñeda-MONEDA); or (c) the same except that the letters “n” or “ñ” were replaced with a visually different letter creating a pseudoword (visually dissimilar [DIS] condition: museca-MUÑECA; moseda-MONEDA). For the purposes of the lexical decision task, we created 132 orthographically legal pseudowords with Wuggy (Keuleers & Brysbaert, Reference Keuleers and Brysbaert2010), half of them with the letter n in an internal position and the other half with the letter ñ in an internal position. The prime-target manipulation for the pseudoword targets was the same as that for the word targets (i.e., ID condition, cepiña-CEPIÑA; SIM condition, cepina-CEPIÑA; DIS condition, cepisa-CEPIÑA). We created three lists to counterbalance the stimuli (e.g., muñeca-MUÑECA in list 1, muneca-MUÑECA in list 2, and museca-MUÑECA in list 3). All prime-target pairs are presented in Appendix A.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted individually or in groups of three or four in a silent room. We employed computers equipped with DMDX (Forster & Forster, Reference Forster and Forster2003) to present the stimuli and register the response time and accuracy of each response. The participants were told that, on each trial, there would be a string of letters on the computer screen. They were asked to respond, as quickly and accurately as possible, whether the string of letters formed a Spanish word or not. For words they had to press a “sí” (yes) button with their right hand and for nonwords they had to press a “no” button with their left hand. In each trial, a pattern mask (i.e., a sequence of #’s) was presented for 500 ms, which was replaced by a lowercase prime during 50 ms (3 refresh cycles in the 60-Hz CRT screen). This was immediately replaced by the target stimulus in uppercase, which remained on the screen until the participant responded or up to 2000 ms—the program automatically encoded an error response (i.e., –2000) if no answer was given before this deadline. All the stimuli were presented in 12-pt Courier New font. The order of the stimuli was fully randomized for each participant, and there were three short breaks during the experiment. The experimental phase was preceded by a practice phase composed of 16 trials of similar characteristics as the experimental trials (8 words and 8 pseudowords). As usual with the masked priming technique, there was no mention of the prime stimuli in the instructions, and when asked in the debriefing after the experiment, none of the participants commented on the presence of briefly presented items. The experimental session took around 12–15 min.

Results

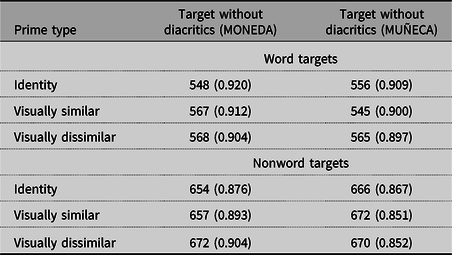

Incorrect responses and very fast responses (less than 250 ms; 4 observations in the word trials [0.07%]) were omitted from the latency analyses. Table 1 displays the mean response times and accuracy in each experimental condition.

Table 1. Mean lexical decision times (in milliseconds) and accuracy (proportion) for word and nonword targets in each condition

To conduct the inferential analyses of the latency data, we employed generalized linear mixed models using the package lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Machler, Balker and Wolker2015) in R (R Core Team, 2019) and we assumed an underlying gamma distribution (see Lo & Andrews, Reference Lo and Andrews2015; Yang & Lupker, Reference Yang and Lupker2019, for discussion of the advantages of this approach).Footnote 2 In the generalized linear mixed models, the fixed factor prime type was encoded as to test the two research questions: whether there is an advantage of the visually similar over the visually dissimilar condition (i.e., SIM vs. DIS); and whether there is an advantage of the ID condition over the SIM condition (see Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018a, Reference Marcet and Perea2018b, for a similar approach). Type of target moneda-type vs. muñeca-type; zero-centered [–0.5 vs. 0.5]) was included as a factor to examine whether it modulated the size of the priming effects. Subjects and items were incorporated as random effects in the models, and we chose the maximal random effect structure model that successfully converged (see Barr, Levy, Scheepers, & Tily, Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013). The final model was GLME_RT = glmer(RT ~ prime_type*target_type + [1|subject] + [1|item], data = wordRT, family = Gamma[link=“identity”]). The analyses of the accuracy data were parallel to those of the latency data except for the use of the binominal distribution (i.e., “family = binomial”; correct responses were encoded as “1” and incorrect responses were encoded as “0”).

Word data

Visually similar versus visually dissimilar conditions

The overall advantage of the visually similar over the visually dissimilar condition was not significant, β = 1.231, SE = 3.474, z = 0.354, p = .723, but this difference was modulated by type of target (interaction: β = 15.147, SE = 3.960, z = 3.825, p < .001). This interaction showed that, for muñeca-type words, responses in the visually similar condition were faster than in the visually dissimilar condition (β = 16.758, SE = 4.610, z = 3.635, p < .001); in contrast, for moneda-type words, response times were essentially the same in the visually similar and visually dissimilar conditions, β = 1.389, SE = 4.227, z < 1, p > .70. The analyses of the accuracy data failed to show any significant effects.

Identity vs. visually similar conditions

In the latency data, we found an advantage of the identity condition over the visually similar condition, β = –15.645, SE = 3.359, z = –4.658, p < .001. This effect interacted with type of word (interaction: β = 24.801, SE = 4.321, z = 5.740, p < .001). This interaction showed that, for muñeca-type words, word identification times were slightly slower in the identity condition than in the visually similar condition, β = 9.654, SE = 4.945, z = –1.952, p = .102, whereas for moneda-type words, word identification times in the identity condition were faster than the visually similar condition, β = –15.197, SE = 4.126, z= –3.684, p < .001.Footnote 3 The analyses of the accuracy data did not show any significant effects.

Nonword data

None of the effects in the latency/accuracy analyses were significant.

Discussion

We designed a masked priming experiment with the lexical decision task to examine whether visual similarity effects occur in a Latin-based orthography (Spanish) when the critical letter was replaced by a consonant differing in a diacritical signs (e.g., n→ñ or ñ→n, as in moñeda-MONEDA or muneca-MUÑECA) and whether these effects were bidirectional (e.g., n↔ñ) or unidirectional (e.g., n→ñ, but not ñ→n). Results showed that, for MONEDA-type words, the visually similar prime moñeda was not more effective than the visually dissimilar prime moseda (567 vs. 568 ms, respectively; i.e., there was no visual similarity effect); furthermore, the visually similar prime moñeda was less effective than the identity prime moneda (567 vs. 548 ms, respectively). This pattern (i.e., SIM = DIS; ID < SIM) extends not only the findings of Perea et al. (Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) in the Arabic script to the Latin script but also the findings of Chetail and Boursain (Reference Chetail and Boursain2019) and Domínguez and Cuetos (Reference Domínguez and Cuetos2018) from vowels to consonants in the Latin script. Nevertheless, the pattern of findings was different for MUÑECA-type words. The visually similar prime muneca was more effective at activating the target word MUÑECA than the visually dissimilar prime moseda (545 vs. 565 ms, respectively; i.e., SIM < DIS). That is, when the critical letter in the prime did not contain a diacritical sign, we found a sizable visual similarity effect (see Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2017, Reference Marcet and Perea2018a, for behavioral evidence; see Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Sigut, Marcet and Perea2019, for electrophysiological evidence). The visually similar prime muneca was highly effective and produced slightly faster word identification times than the identity prime muñeca (a nonsignificant 9 ms difference). As indicated above, we prefer to remain cautious about this small difference and prefer to interpret it as a null effect (i.e., ID = SIM; see Perea et al., Reference Perea, Duñabeitia and Carreiras2008, for a similar pattern). We now discuss the consequences of these findings for neural and computational models of word recognition.

The present experiment reconciles several seemingly conflicting findings in the literature regarding how visual letter similarity modulates word processing, and it also offers new insights on the processing of words containing consonants with diacritical signs. On the one hand, the current experiment showed that, for prime stimuli with no letters containing diacritical signs, visually similar primes are more effective than visually dissimilar primes at activating a target word (e.g., muneca-MUÑECA faster than museca-MUÑECA), thus providing further empirical evidence to the idea of perceptual noise at encoding letter identities in the first moments of word processing (i.e., initially, the letter n may be initially processed as the letter ñ), as proposed by the Bayesian reader model (Norris & Kinoshita, Reference Norris and Kinoshita2012). On the other hand, the current experiment showed that prime stimuli containing a letter with a diacritical sign (i.e., a visually salient feature) are processed differently from their counterparts without those signs, and comparably to other visually dissimilar letters (e.g., for the target word MONEDA, the prime moñeda is not more effective than the control prime moseda). Taken together, this dissociative pattern strongly suggests that the abstract letter detectors activated by a consonantal letter with diacritical signs are not the same as those activated by the base letter without diacritical signs (i.e., “ñ” does not activate “n”), but at the same time the base letter without the diacritical sign does activate its accented counterpart (i.e., “n” activates “ñ”). This pattern poses some limits to the generality of the effects of visual similarity and it stresses the importance of the encoding of diacritical signs in the first moments of processing.

The present data also allow us to reinterpret the findings from Perea et al. (Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) in Arabic: the lack of an advantage of the visually similar replaced-consonant prime ![]() over the visually dissimilar replaced-consonant prime

over the visually dissimilar replaced-consonant prime ![]() at activating the target word

at activating the target word ![]() is not due to the singular role of diacritical signs in Arabic script, as Perea et al. (Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) proposed. A more parsimonious explanation is that the lack of visual similarity effects with primes containing letters with diacritical signs is a more general phenomenon: it occurs not only in Arabic but also in the Latin-based orthographies with accented vowels (tâper-TAPER = tuper-TAPER; Chetail & Boursain, Reference Chetail and Boursain2019; Domínguez & Cuetos, Reference Domínguez and Cuetos2018) and with consonant letters (moñeda-MONEDA = moseda-MONEDA), as in the current experiment.

is not due to the singular role of diacritical signs in Arabic script, as Perea et al. (Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2016, Reference Perea, Abu Mallouh, Mohammed, Khalifa and Carreiras2018) proposed. A more parsimonious explanation is that the lack of visual similarity effects with primes containing letters with diacritical signs is a more general phenomenon: it occurs not only in Arabic but also in the Latin-based orthographies with accented vowels (tâper-TAPER = tuper-TAPER; Chetail & Boursain, Reference Chetail and Boursain2019; Domínguez & Cuetos, Reference Domínguez and Cuetos2018) and with consonant letters (moñeda-MONEDA = moseda-MONEDA), as in the current experiment.

We acknowledge that the present experiment comes with several limitations. First, although most effects obtained with the masked priming paradigm have been extended to a sentence reading using, for instance, Rayner’s (Reference Rayner1975) boundary, it is important to examine in future research the role of diacritics in a standard reading scenario (e.g., see Johnson, Perea, & Rayner, Reference Johnson, Perea and Rayner2007, for evidence of transposed-letter similarity effects during reading; see also Marcet & Perea, Reference Marcet and Perea2018b, for evidence of visual similarity effects during reading). In a ideal scenario, this could be combined with a co-registration of the fixation-related potentials (see Degno et al., Reference Degno, Loberg, Zang, Zhang, Donnelly and Liversedge2019). Second, Spanish orthography only contains one consonant letter with a diacritical sign (i.e., ñ), and this may limit the generality of the findings. This would also be the case with other languages such as French (the only diacritical consonant in French is ç). Further research is necessary to examine whether the present pattern of findings also holds in Latin-bases languages that contain multiple consonants with diacritical signs (e.g., Czech contains eight consonants with diacritical signs: č, ď, ň, ř, š, ť, ý, ž). This may also be tested in other scripts that also employ diacritical signs (e.g., Thai and Japanese Kana). Third, the diacritical sign of the letter ñ in Spanish is placed above its base letter (n). Given that the upper part of letters/words play a special role during word recognition and reading in Latin-based orthographies (e.g., Huey, 1968/Reference Huey1908; Perea, Reference Perea2012), it is important to further examine whether there are differences between the processing of diacritical letters and their counterparts when the diacritics are placed above or below their base letters (e.g., č vs. ç).

In sum, the dissociative pattern of priming effects depending on whether the visually similar substituted letter contains diacritical signs (e.g. moñeda-MONEDA vs. muneca-MUÑECA) constrains the links between the “feature” and “letter” levels in models of written word recognition. Note that the vast majority of European languages contain letters with diacritical signs. When implementing a computational model of word recognition (e.g., using the easyNet software; see Adelman, Gubian, & Davis, Reference Adelman, Gubian and Davis2018) in languages with diacritical letters, it is necessary to include both the original (base) letters and their diacritical counterpart as separate units at the letter level. Furthermore, at least in Spanish, the base letters should be confusable with their accented counterpart during the first moments of word processing (i.e., n would provide some evidence consistent with the letter ñ: a visual similarity effect), but the letters with diacritical signs should not be confusable with their base letters (i.e., ñ would not activate n). Further research in orthographies with multiple diacritical consonants (e.g., Czech) is necessary to examine whether this pattern is modulated by the distinctiveness of the diacritical sign ~ in Spanish.

Funding

This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (PRE2018-083922, PSI2017-86210-P).

Appendix A List of words and pseudowords in the experiment

The stimuli are presented as quadruplets: identity prime, visually similar prime, visually dissimilar prime, and TARGET

Word targets: montañero, montanero, montasero, MONTAÑERO; señal, senal, sesal, SEÑAL; pestañas, pestanas, pestasas, PESTAÑAS; castañas, castanas, castasas, CASTAÑAS; tamaño, tamano, tamaso, TAMAÑO; pequeño, pequeno, pequeso, PEQUEÑO; diseñador, disenador, disesador, DISEÑADOR; añadir, anadir, asadir, AÑADIR; leñador, lenador, lesador, LEÑADOR; diseño, diseno, diseso, DISEÑO; gruñón, grunón, grusón, GRUÑÓN; meñique, menique, mesique, MEÑIQUE; bañera, banera, basera, BAÑERA; albañil, albanil, albasil, ALBAÑIL; dañar, danar, dasar, DAÑAR; ermitaño, ermitano, ermitaso, ERMITAÑO; coñac, conac, cosac, COÑAC; compañero, companero, compasero, COMPAÑERO; champiñón, champinón, champisón, CHAMPIÑÓN; hazaña, hazana, hazasa, HAZAÑA; cabaña, cabana, cabasa, CABAÑA; engañar, enganar, engasar, ENGAÑAR; rebaño, rebano, rebaso, REBAÑO; contraseña, contrasena, contrasesa, CONTRASEÑA; cuñado, cunado, cusado, CUÑADO; risueño, risueno, risueso, RISUEÑO; extrañar, extranar, extrasar, EXTRAÑAR; ceñido, cenido, cesido, CEÑIDO; extraño, extrano, extraso, EXTRAÑO; señora, senora, sesora, SEÑORA; compañía, companía, compasía, COMPAÑÍA; telaraña, telarana, telarasa, TELARAÑA; enseñar, ensenar, ensesar, ENSEÑAR; puñetazo, punetazo, pusetazo, PUÑETAZO; puñado, punado, pusado, PUÑADO; niñera, ninera, nisera, NIÑERA; cumpleaños, cumpleanos, cumpleasos, CUMPLEAÑOS; riñón, rinón, risón, RIÑÓN; otoño, otono, otoso, OTOÑO; brasileño, brasileno, brasileso, BRASILEÑO; rasguño, rasguno, rasguso, RASGUÑO; migraña, migrana, migrasa, MIGRAÑA; cigüeña, cigüena, cigüesa, CIGÜEÑA; buñuelo, bunuelo, busuelo, BUÑUELO; empeño, empeno, empeso, EMPEÑO; pañuelo, panuelo, pasuelo, PAÑUELO; piraña, pirana, pirasa, PIRAÑA; tacaño, tacano, tacaso, TACAÑO; preñada, prenada, presada, PREÑADA; viñedo, vinedo, visedo, VIÑEDO; ruiseñor, ruisenor, ruisesor, RUISEÑOR; lasaña, lasana, lasasa, LASAÑA; acompañar, acompanar, acompasar, ACOMPAÑAR; muñeca, muneca, museca, MUÑECA; dueño, dueno, dueso, DUEÑO; cañería, canería, casería, CAÑERÍA; mañana, manana, masana, MAÑANA; sureño, sureno, sureso, SUREÑO; navideño, navideno, navideso, NAVIDEÑO; español, espanol, espasol, ESPAÑOL; cariño, carino, cariso, CARIÑO; araña, arana, arasa, ARAÑA; puñal, punal, pusal, PUÑAL; carroña, carrona, carrosa, CARROÑA; entrañable, entranable, entrasable, ENTRAÑABLE; desempeño, desempeno, desempeso, DESEMPEÑO; semifinal, semifiñal, semifisal, SEMIFINAL; honor, hoñor, hosor, HONOR; doctrina, doctriña, doctrisa, DOCTRINA; remolino, remoliño, remoliso, REMOLINO; bonito, boñito, bosito, BONITO; hermano, hermaño, hermaso, HERMANO; municipal, muñicipal, musicipal, MUNICIPAL; vacuna, vacuña, vacusa, VACUNA; tribuna, tribuña, tribusa, TRIBUNA; senado, señado, sesado, SENADO; laguna, laguña, lagusa, LAGUNA; villano, villaño, villaso, VILLANO; llenar, lleñar, llesar, LLENAR; hormona, hormoña, hormosa, HORMONA; avena, aveña, avesa, AVENA; enamorar, eñamorar, esamorar, ENAMORAR; panel, pañel, pasel, PANEL; camioneta, camioñeta, camioseta, CAMIONETA; purpurina, purpuriña, purpurisa, PURPURINA; molino, moliño, moliso, MOLINO; casino, casiño, casiso, CASINO; oxígeno, oxígeño, oxígeso, OXÍGENO; harina, hariña, harisa, HARINA; calcetines, calcetiñes, calcetises, CALCETINES; género, géñero, gésero, GÉNERO; coronar, coroñar, corosar, CORONAR; genética, geñética, gesética, GENÉTICA; clonar, cloñar, closar, CLONAR; persona, persoña, persosa, PERSONA; minuto, miñuto, misuto, MINUTO; teléfono, teléfoño, teléfoso, TELÉFONO; luminoso, lumiñoso, lumisoso, LUMINOSO; oficina, oficiña, oficisa, OFICINA; limonada, limoñada, limosada, LIMONADA; sirena, sireña, siresa, SIRENA; moneda, moñeda, moseda, MONEDA; matrimonio, matrimoñio, matrimosio, MATRIMONIO; enero, eñero, esero, ENERO; túnel, túñel, túsel, TÚNEL; feminista, femiñista, femisista, FEMINISTA; monitor, moñitor, mositor, MONITOR; plátano, plátaño, plátaso, PLÁTANO; reponer, repoñer, reposer, REPONER; matrona, matroña, matrosa, MATRONA; moreno, moreño, moreso, MORENO; propina, propiña, propisa, PROPINA; iguana, iguaña, iguasa, IGUANA; trueno, trueño, trueso, TRUENO; vinagre, viñagre, visagre, VINAGRE; sábana, sábaña, sábasa, SÁBANA; vitamina, vitamiña, vitamisa, VITAMINA; aduana, aduaña, aduasa, ADUANA; bienestar, bieñestar, biesestar, BIENESTAR; escena, esceña, escesa, ESCENA; arena, areña, aresa, ARENA; abanico, abañico, abasico, ABANICO; camino, camiño, camiso, CAMINO; leona, leoña, leosa, LEONA; colonial, coloñial, colosial, COLONIAL; cocinar, cociñar, cocisar, COCINAR; semana, semaña, semasa, SEMANA; lunes, luñes, luses, LUNES; sauna, sauña, sausa, SAUNA; avioneta, avioñeta, avioseta, AVIONETA; fotogénico, fotogéñico, fotogésico, FOTOGÉNICO; aceitunas, aceituñas, aceitusas, ACEITUNAS

Nonword targets: mompiñero, mompinero, mompisero, MOMPIÑERO; teñol, tenol, tesol, TEÑOL; pesceñas, pescenas, pescesas, PESCEÑAS; casciña, cascina, cascisa, CASCIÑA; tasiño, tasino, tasiso, TASIÑO; pefioño, pefiono, pefioso, PEFIOÑO; misiñador, misinador, misisador, MISIÑADOR; añider, anider, asider, AÑIDER; veñifor, venifor, vesifor, VEÑIFOR; simeño, simeno, simeso, SIMEÑO; pluñón, plunón, plusón, PLUÑÓN; señoque, senoque, sesoque, SEÑOQUE; tuñera, tunera, tusera, TUÑERA; arpiñol, arpinol, arpisol, ARPIÑOL; hañar, hanar, hasar, HAÑAR; expetaño, expetano, expetaso, EXPETAÑO; viñac, vinac, visac, VIÑAC; cosmañera, cosmanera, cosmasera, COSMAÑERA; chusdiñón, chusdinón, chusdisón, CHUSDIÑÓN; nafaña, nafana, nafasa, NAFAÑA; cepiña, cepina, cepisa, CEPIÑA; esviñar, esvinar, esvisar, ESVIÑAR; gepiño, gepino, gepiso, GEPIÑO; conflageño, conflageno, conflageso, CONFLAGEÑO; ciñuda, cinuda, cisuda, CIÑUDA; simuaño, simuano, simuaso, SIMUAÑO; embriñar, embrinar, embrisar, EMBRIÑAR; ciñafo, cinafo, cisafo, CIÑAFO; embriño, embrino, embriso, EMBRIÑO; vuñera, vunera, vusera, VUÑERA; cosgañía, cosganía, cosgasía, COSGAÑÍA; bemacaña, bemacana, bemacasa, BEMACAÑA; empiñor, empinor, empisor, EMPIÑOR; muñitezo, munitezo, musitezo, MUÑITEZO; piñido, pinido, pisido, PIÑIDO; diñeto, dineto, diseto, DIÑETO; cilcheaños, cilcheanos, cilcheasos, CILCHEAÑOS; bañón, banón, basón, BAÑÓN; oxaño, oxano, oxaso, OXAÑO; framigeño, framigeno, framigeso, FRAMIGEÑO; sisfuño, sisfuno, sisfuso, SISFUÑO; pifliña, piflina, piflisa, PIFLIÑA; logüiña, logüina, logüisa, LOGÜIÑA; luñuilo, lunuilo, lusuilo, LUÑUILO; egjeño, egjeno, egjeso, EGJEÑO; sañiolo, saniolo, sasiolo, SAÑIOLO; bugaña, bugana, bugasa, BUGAÑA; tariño, tarino, tariso, TARIÑO; triñeda, trineda, triseda, TRIÑEDA; veñico, venico, vesico, VEÑICO; riabeñor, riabenor, riabesor, RIABEÑOR; tuvoña, tuvona, tuvosa, TUVOÑA; amaspañar, amaspanar, amaspasar, AMASPAÑAR; duñesa, dunesa, dusesa, DUÑESA; gauño, gauno, gauso, GAUÑO; ciñagía, cinagía, cisagía, CIÑAGÍA; pañila, panila, pasila, PAÑILA; dujeño, dujeno, dujeso, DUJEÑO; gadedeño, gadedeno, gadedeso, GADEDEÑO; esciñel, escinel, escisel, ESCIÑEL; caceño, caceno, caceso, CACEÑO; aciña, acina, acisa, ACIÑA; muñol, munol, musol, MUÑOL; cilleña, cillena, cillesa, CILLEÑA; esgreñadre, esgrenadre, esgresadre, ESGREÑADRE; desabseño, desabseno, desabseso, DESABSEÑO; mesevinal, meseviñal, mesevisal, MESEVINAL; gonel, goñel, gosel, GONEL; siptrino, siptriño, siptriso, SIPTRINO; pemonica, pemoñica, pemosica, PEMONICA; vonato, voñato, vosato, VONATO; fervino, ferviño, ferviso, FERVINO; runecibal, ruñecibal, rusecibal, RUNECIBAL; tavina, taviña, tavisa, TAVINA; clicuna, clicuña, clicusa, CLICUNA; menide, meñide, meside, MENIDE; pogena, pogeña, pogesa, POGENA; fitrino, fitriño, fitriso, FITRINO; blenar, bleñar, blesar, BLENAR; cerlona, cerloña, cerlosa, CERLONA; adeno, adeño, adeso, ADENO; anabopar, añabopar, asabopar, ANABOPAR; manil, mañil, masil, MANIL; canauresa, cañauresa, casauresa, CANAURESA; piedurina, pieduriña, piedurisa, PIEDURINA; socino, sociño, sociso, SOCINO; cicano, cicaño, cicaso, CICANO; ixédeno, ixédeño, ixédeso, IXÉDENO; balana, balaña, balasa, BALANA; caldetunes, caldetuñes, caldetuses, CALDETUNES; cíneva, cíñeva, císeva, CÍNEVA; ceconar, cecoñar, cecosar, CECONAR; benítira, beñítira, besítira, BENÍTIRA; blinar, bliñar, blisar, BLINAR; paslona, pasloña, paslosa, PASLONA; sinuro, siñuro, sisuro, SINURO; helíbono, helíboño, helíboso, HELÍBONO; burenoso, bureñoso, buresoso, BURENOSO; odenica, odeñica, odesica, ODENICA; binolado, biñolado, bisolado, BINOLADO; ticeno, ticeño, ticeso, TICENO; sonuva, soñuva, sosuva, SONUVA; mifledonio, mifledoñio, mifledosio, MIFLEDONIO; erena, ereña, eresa, ERENA; súnil, súñil, súsil, SÚNIL; gesenista, geseñista, gesesista, GESENISTA; ponatol, poñatol, posatol, PONATOL; blácino, bláciño, bláciso, BLÁCINO; dovonir, dovoñir, dovosir, DOVONIR; saflona, safloña, saflosa, SAFLONA; soreno, soreño, soreso, SORENO; trubana, trubaña, trubasa, TRUBANA; ivaena, ivaeña, ivaesa, IVAENA; chaeno, chaeño, chaeso, CHAENO; bonicre, boñicre, bosicre, BONICRE; tavina, taviña, tavisa, TAVINA; lumadina, lumadiña, lumadisa, LUMADINA; oguona, oguoña, oguosa, OGUONA; tuenostar, tueñostar, tuesostar, TUENOSTAR; esvuna, esvuña, esvusa, ESVUNA; useno, useño, useso, USENO; amacina, amaciña, amacisa, AMACINA; cacina, caciña, cacisa, CACINA; beono, beoño, beoso, BEONO; canotiel, cañotiel, casotiel, CANOTIEL; covanar, covañar, covasar, COVANAR; mecina, meciña, mecisa, MECINA; bunis, buñis, busis, BUNIS; taena, taeña, taesa, TAENA; amoinesa, amoiñesa, amoisesa, AMOINESA; fosofínico, fosofíñico, fosofísico, FOSOFÍNICO; amoilenas, amoileñas, amoilesas, AMOILENAS

the visually similar one-letter replaced prime

the visually similar one-letter replaced prime  (compare

(compare  and

and  is no more effective than the visually dissimilar one-letter replaced prime

is no more effective than the visually dissimilar one-letter replaced prime  Here we examined whether this dissociative pattern is due to the special role of diacritics during word processing. We conducted a masked priming lexical decision experiment in Spanish using target words containing one of two consonants that only differed in the presence/absence of a diacritical sign:

Here we examined whether this dissociative pattern is due to the special role of diacritics during word processing. We conducted a masked priming lexical decision experiment in Spanish using target words containing one of two consonants that only differed in the presence/absence of a diacritical sign: