Introduction

Finely worked Classic Maya jadeite (hereafter referred to as jade) ornaments were unique objects often imbued with inalienable status. They contrast with objects produced in great quantities, such as moulded figurines whose repetition, imagery and more banal raw material allowed for widespread circulation and popular consumption in many regions of the Maya area. Carved jade ornaments have been consistently viewed as symbols of wealth and status, which is reinforced by its hardness, toughness, colour, rarity, symbolism and workmanship, and by the individual ornaments’ entangled histories with their artisans, gift givers and owners (Digby Reference Digby1972; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Reese-Taylor, Mora-Marin, Masson and Freidel2002; Joyce Reference Joyce, Dyke and Alcock2003; Taube Reference Taube2005; Rochette Reference Rochette and Hirth2009; Kovacevich Reference Kovacevich2013; Andrieu et al. Reference Andrieu, Rodas and Luin2014; Prager & Braswell Reference Prager and Braswell2016). Jade ornaments possessing the aesthetics, iconography and workmanship of elite artistry were restricted to the highest-ranking families of ancient Maya society, and they reciprocally symbolised their titles, positions and status.

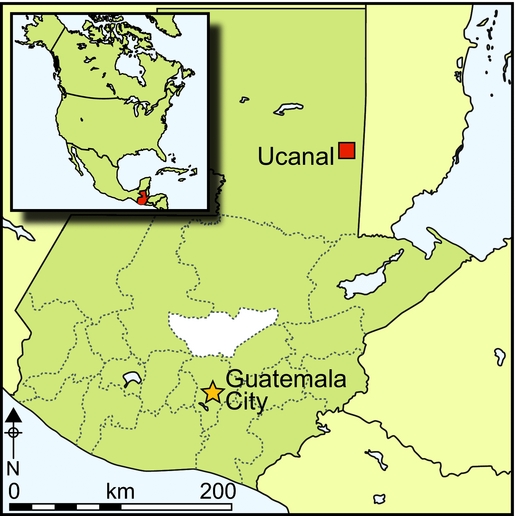

Although scholars have examined these different characteristics of jade in iconographic analyses, identified jade workshops and incorporated jade into political-economic studies, the actual weight of jade objects often goes unnoticed. As such, this paper considers weight as an analytical lens through which to explore jade head pendants in the round. We find that: 1) weight relates to ornament function or type; 2) weight has rich metaphorical meanings; 3) its consideration allows for a phenomenological approach often overlooked among studies of jade; and 4) it provides a bridge to other materials, people and practices beyond the royal body. To explore the implications of weight in the analysis of jade head pendants, we highlight a jade ornament recovered in 2016 from the archaeological site of Ucanal, Petén, in Guatemala, by the Proyecto Arqueólogico Ucanal (Figure 1). This jade head pendant in the round, at 180 × 113.3 × 79.8mm and 2363g, is the largest and probably the heaviest Classic-period pendant of its kind recovered in the Maya area to date (Figure 2). Maya head pendants in the round possess drilled holes at the sides (used for suspension) and high-relief or rounded carving of the face (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974: 90–192).

Figure 1. Map of south-eastern Petén in Guatemala, showing the location of the Ucanal site (adapted from Mejía Reference Mejía2002: fig. 1).

Figure 2. Ucanal jade head pendant in the round, UCPV018 (photograph: C. Halperin).

The jade head pendant from Ucanal, Guatemala

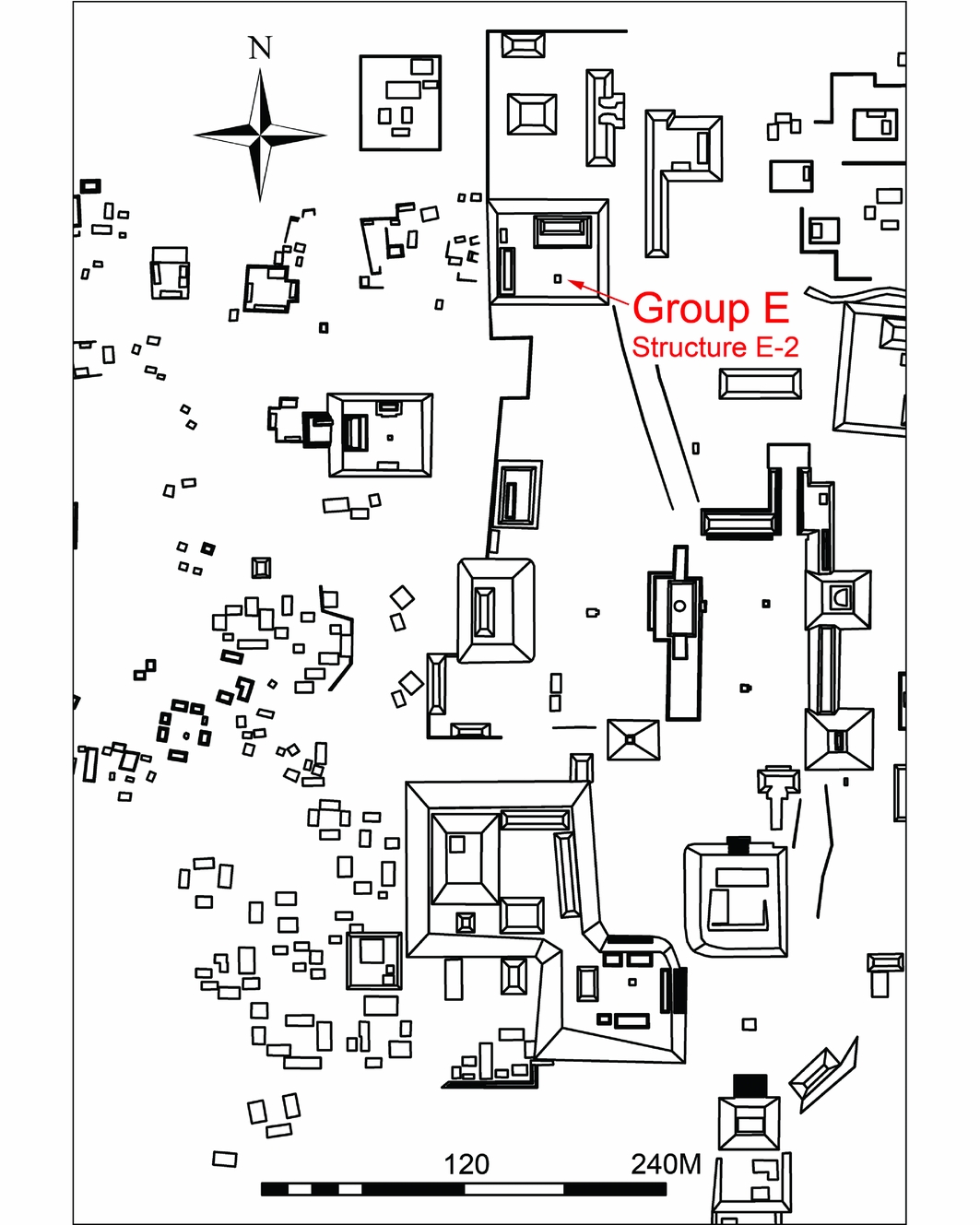

The Ucanal jade head pendant was uncovered in a Terminal Classic lip-to-lip ceramic cache (offering 3-1) located on the eastern side of a low, centrally situated altar in group E (Mongelluzzo Reference Mongelluzzo, Halperin and Garrido2016) (Figure 3). Due to its large size and location adjacent to public ceremonial architecture, the group is considered to have been a royal or elite architectural group. The cache was located adjacent to the grave of an adult male (burial 3-1), who was buried in a prone (facedown) position (Figure 4). The long bones were articulated and in excellent condition, but the individual was missing his torso and part of his cranium. Although the practice of putting small altars at the centre of residential patios has a long history in Central Mexico and Yucatán, it was rare in the southern Maya lowlands until the Terminal Classic period (c. 800–950 AD) (Sabloff & Rathje Reference Sabloff and Rathje1975; Diehl Reference Diehl1983; Manzanilla Reference Manzanilla, Hendon and Joyce2004; Becker Reference Becker, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009; Hutson Reference Hutson2009). The site of Ucanal flourished during the Terminal Classic period, as it participated in extensive trade networks, was at the height of its urban population and underwent a series of major monumental construction projects (Laporte & Mejía Reference Laporte and Mejía2002; Mejía Reference Mejía2002; Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Garrido, Mongelluzzo, Pérez, Wolf and Bracken2015).

Figure 3. Map of a section of Ucanal's site core showing the location of group E.

Figure 4. Plan map and photograph of offering 3-1 and burial 3-1 at the eastern side of structure E-2, group E (operation 3), at the Ucanal site (drawing and photograph: R. Mongelluzzo).

Jade is fairly widespread throughout eastern Guatemala, particularly in the deep tectonic subduction zone of the Upper and Middle Motagua River Valley (Seitz et al. Reference Seitz, Harlow, Sisson and Taube2001; Taube et al. Reference Taube, Hruby, Romero, Hruby, Braswell and Mazariegos2011). High-quality bright green or blue jade, however, is relatively rare and exists only in a few areas in the jade-bearing regions. Different colours and qualities in the jade region are recognisable from source area to source area. The Ucanal head pendant is a milky green, ‘apple’ jade probably deriving from the lower altitude portions of the Middle Motagua region—perhaps near Guaytan or farther up the river. A systematic project sourcing these different jades is required to confirm this assertion.

The Ucanal jade head pendant falls into the category of round-relief pendants identified by Tatiana Proskouriakoff (Reference Proskouriakoff1974) in her classification of jade ornaments from Chichén Itzá in Mexico. These pendants differ stylistically from other types, such as jade pendant plaques, jade silhouette plaques, two-sided jade carvings and low-relief pendants. The Ucanal head is somewhat asymmetrical, suggesting that the artisan was guided by the original shape of the cobble and was not overly concerned in adhering to more canonical Maya artistic styles. The carving of facial features is also slightly shallower than observed on other Classic Maya head pendants. The incised detail of the curls at the side of the Ucanal jade head pendant may represent the figure's ears, or scrolls typically found on head foliage of the Maize deity (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974; Taube Reference Taube2005; Taube & Ishihara-Brito Reference Taube, Ishihara-Brito, Pillsbury, Doutriaux, Ishihara-Brito and Tokovinine2012). Likewise, the pecked ridge at the top of the Ucanal head may represent the modified cranium of the Maize god. This ridge, however, also resembles sculpted and unpolished channels found on some cobble hammer stones and string saw cores, where a perishable handle is attached to the stone. Indeed, remnants of percussion scars are apparent on the polar ends of the head, suggesting that it may have had a different use-life before it was finally transformed into a pendant. Its use as a pendant in its final form, however, is indicated by two perforated suspension holes that were drilled into the top edges of the head.

Functional distinctions

The weight of the Ucanal pendant is substantial, and thus we propose here that weight—and size in general—provides a suitable criterion for distinguishing different jade head pendants in the round. Unfortunately, few publications provide information on ornament weights, underscoring the ambivalence previous researchers have had regarding this particular feature. Nonetheless, jade size dimensions can be used as a proxy for weight to compare provenanced and unprovenanced jade head pendants in the round. These comparisons reveal a natural break in the distribution of pendant sizes and, by implication, weights, which we suggest relates to their function or placement on the body (Figure 5; Appendix 1 in the online supplementary material (OSM)). The small pendants probably served as chest or necklace pendants. The large ones, which all have drilled pendant holes (similar to the small ones) at the upper sides of the head, were probably belt ornaments (see Figure 6 for two examples of large belt head pendants in the round with dangling celts). Such placements make sense, as heavier weights are more manageable if they are closer to the body's centre of gravity.

Figure 5. Size comparison of Classic Maya jade pendants in the round with drawings of examples from: top left) Chichén Itzá, Mexico, with texts mentioning Piedras Negras (after Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974: 140–41); top middle) unprovenanced, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (drawing: C. Halperin, after Miller & Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004: pl. 28); top right) Ucanal, UCPV018 (drawing: Danilo Hernandez); lower right) unprovenanced, British Museum (drawing: C. Halperin, after Schele & Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986: pl. 21).

Figure 6. Ucanal stela 4 (drawing: C. Halperin, after Graham Reference Graham1980: 2–159).

Of the four large jade head pendants in the round, only the Ucanal head pendant has been recovered from a secure archaeological context. Part of the history of these unprovenanced specimens, however, can be understood from inscribed hieroglyphic texts. One of the large pendants, currently housed in the British Museum, is reported to have been found near Comayagua, Honduras. Text on its reverse side that references K'inich K'an Joy Chitam, a son of K'inich Janab Pakal, the famous seventh-century king of Palenque, suggests that it travelled some distance over its life-history (Schele & Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986: 81, pl. 21). The largest of the four pendants, which is housed in the National Gallery of Australia, is paired with a stone box with text indicating that the head was made for a Tonina king, K'inich Tuun Chapat (Miller & Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004: pl. 28). As the head pendant and box have no archaeological context, it is impossible to know if the box was originally found with the head pendant, or if the two were placed together more recently. These large jade head pendants in the round are also comparable to a mosaic jade belt mask found on Pakal's sarcophagus lid in a sealed chamber within the Temple of Inscriptions, Palenque (Miller & Martin Reference Miller and Martin2004: 236, pl. 133). The belt was produced, however, with multiple jade pieces, rather than carved from a single cobble, as is the case with the jade head pendants in the round. Interestingly, a jade pendant in the round found in the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá, with texts indicating that it belonged to a Late Classic ruler from Piedras Negras, is often assumed to be a belt ornament, but is closer in size to the small jade head pendants in the round (Figure 5).

Weight as a metaphor for the responsibilities of political office

Beyond functionalist arguments, weight had rich meanings for the Maya. As discussed by Karl Taube (Reference Taube1989: 42–43) and elaborated on by Brian Stross (Reference Stross1988) and David Stuart (Reference Stuart, Guernsey and Reilly2006), the Classic Maya word for ‘burden’ or ‘cargo’ is ikaatz, as attested in Tzeltal and Tzotzil Maya. This word was inscribed in hieroglyphics on portable jade artefacts and labelled cloth bundles presumably containing jade ornaments. In this sense, jade ornaments were symbols of the burdens of political office and elite rank. Such a burden probably refers to the responsibilities of the highest royal officials who wore these instruments of power and had to look after their people, mobilise public performances and ensure the fertility of the earth (Stross Reference Stross1988: 118). These burdens, however, may also have been tied to the responsibilities of lower-ranked lords in giving precious jade ornaments as gifts or tributes tohigher-ranked lords in the webs of alliances and burdens that both bound and still bind polities together (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey and Reilly2006: 131). Among contemporary Maya groups today, the metaphor of burden is also explicit in the holding of political-religious office, as these positions are known in Spanish as ‘cargos’ or burdens (Cancian Reference Cancian1965; Vogt Reference Vogt1969). The holding of a cargo office confers prestige on the cargo-holder, and this prestige increases with cargo rank. In turn, the cargo holders devote an enormous amount of time to the position and take on the burden of paying for and supplying the resources needed for the execution of community ceremonies (Cancian Reference Cancian1965: 80–106; Vogt Reference Vogt1969: 572–81). These financial and labour burdens likewise increase with the status of cargo holders. Such metaphors of weight are not necessarily unique to the Maya. For example, the stone ballgame gear (yokes, hachas and palmas) from Veracruz and the southern Pacific coast of Mesoamerica evokes a sense of heaviness in comparison to its perishable cloth and wooden counterparts (Shook & Marquis Reference Shook and Marquis1996; Koontz Reference Koontz2009). Even though some of these ballgame accoutrements are larger than human-sized versions in leather and cloth, it is not their size but their weight that give them a sense of monumentality. Too heavy to wear during the game itself, the stone yokes, hachas and palmas were the burdens of political officials who commissioned and incorporated them into their politico-religious rites.

The phenomenology of jade ornaments

While many scholars have explored the semiotics of jade, it is also worth considering the experiences of wearing such jewellery (although see Taube & Ishihara-Brito Reference Taube, Ishihara-Brito, Pillsbury, Doutriaux, Ishihara-Brito and Tokovinine2012 for the acoustical properties of jade). Thus, rather than just a metaphor for the burdens of office, jade ornaments would have heavily weighed down those who wore them. In this perspective, the weight of jade ornaments can be seen as an embodied part of ritual work, serving as part of the sacrifice and dedication of Maya rulers to their gods.

In calculating the weight of a costume from Ucanal's stela 4, using comparable Maya jade ornaments from collections at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. (Taube & Ishihara-Brito Reference Taube, Ishihara-Brito, Pillsbury, Doutriaux, Ishihara-Brito and Tokovinine2012), and from archaeological collections, we estimate that the ruler would have had to carry around an extra 11.43kg (25.2lbs) (Figure 6; Appendix 2 in the OSM). Such a calculation does not include the weight and cumbersomeness of his headdress, shell tinklers or clothing. In other Classic-period depictions, the weight of ear spools and pendants are so heavy they must be counterbalanced by ornaments on the back of the ear or neck (e.g. Schele & Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986: fig. II.6, II.7). A recently excavated jade pendant plaque in the shape of an ik’ symbol from the site of Pusilhá in Belize indicates that Maya carved monuments did not necessarily exaggerate the size and shapes of jade jewellery, which shows them as large relative to the body (Prager & Braswell Reference Prager and Braswell2016). Similarly, an Early Classic burial from the El Diablo complex at El Zotz, which contained 1.07kg of jade jewellery (including beads, celts, plaques, earspools and mosaic tesserae), further underscores the weight of such accoutrements (Hruby Reference Hruby, Houston, Newman, Román and Garrison2015).

Figure 7. Non-royal people carrying palanquins and litters on Classic-period, ‘non-official’ media: a) effigy palanquin with seated ruler, graffiti, Caracol, structure B-20-2nd (drawing: Luis F. Luin, after Chase & Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Inomata and Houston2001: fig. 4.12); b) effigy palanquin with seated ruler, graffiti, Tikal structure 5D-65 (drawing: Luis F. Luin, after Trik & Kampen Reference Trik and Kampen1983: fig. 72); c) base of palanquin with porters and drum player, moulded figurine, Lubaantun (drawing: C. Halperin, after Wegars Reference Wegars1977: fig. 18d); d) litter of ruler carried by porters, moulded figurine, Lubaantun (drawing: Luis F. Luin, after Wegars Reference Wegars1977: fig. 19c).

The ceremonial occasions on which such costumes were worn often included dances performed by the ruler and his family (Grube Reference Grube1992; Looper Reference Looper2009). Dancing with such weight would have been more strenuous than merely walking slowly or sitting quietly with one's finery, as seen with British royal coronation ceremonies. It is perhaps ironic that dancing, which requires one to be light on one's feet, was often experienced as heavy because the royal body was weighed down with ornamentation.

In the contemporary Maya dance-drama Rabinal Achi, the Eagle and Jaguar characters carry back racks very similar to those from Classic-period depictions of the Maize god who dances his way up to the earth from the underworld (Tedlock Reference Tedlock2003: 139–42). These back racks are wider and taller than the actors themselves, and contain a wooden effigy at the centre. These effigies are referred to in K'iche’ as patam or ‘burden’ (Tedlock Reference Tedlock2003: 139–42). Hutcheson (Reference Hutcheson2009) finds that the experiential aspects of dance during some K'iche’ Maya dance-dramas today were as, if not more, important than the narrative plot. In his description of the actors, he notes:

the central importance of dance in all of these performances cannot be overstated. The masked dance-dramas are true theaterworks, with characters, speeches, and plotlines (ostensibly, at least), but the devotional sacrifice they represent is actualized by dancing (Hutcheson Reference Hutcheson2009: 871).

The act of dressing up in jade ornamentation and other costume elements may have been an important embodied way of entering into liminal time, thereby signalling the start of the performance. Classic-period murals and polychrome pots often make reference to the importance of dressing scenes, whether these scenes are historical or mythological (Taube Reference Taube1989; Looper Reference Looper2009: 114–22; Miller & Brittenham Reference Miller and Brittenham2013). As in modern dressing ceremonies of a Western bride whereby the transformation of a woman into a bride commences not with her walking down the aisle, but with her donning her dress and veil, Classic Maya dressing scenes also highlight when a performance began and how such dressing paved the way for transformative acts.

Burdens of burdens and other weights

A consideration of weight and its burdens also points to the many anonymous people who contributed to the substantial responsibilities of office and the privileges of elites. For example, while carved stone monuments and lintels focus almost exclusively on the royal body (Coe et al. Reference Coe, Shook and Satterthwaite1961; Freidel & Guenter Reference Freidel and Guenter2003), small-scale, unofficial images hint at the anonymous people who literally carried the kings and queens—and thus, by default, their heavy jade ornaments (Figure 7). Rare examples of these porters appear in the graffiti at Tikal and moulded ceramic figurines from Lubaantun in Belize (Wegars Reference Wegars1977; Trik & Kampen Reference Trik and Kampen1983; Halperin Reference Halperin2014). Looper (Reference Looper2009) has argued that the procession of palanquins was not only a part of ceremonial war celebrations and period-ending rites, but also of dance performances. Lintel 3 from Tikal temple 4, for example, showcases a palanquin ceremony that commemorates a victory over El Perú. The lintel text also mentions dancing, suggesting that it was a key component in the ceremonial events. Additionally, Fray Antonio de Ciudad Real, in a visit to a Yucatecan village in 1588, documents the central role of a palanquin in a dance performance and notes that even the porters who carried the performing ruler danced under the burden of the heavy litter. He states:

the Indians brought out to welcome him a strange devise and it was: litter-like frames and upon them a tower round and narrow, in the manner of a pulpit, visible from the waist up, was an Indian very well and nicely dressed, who with rattles of the country in one hand, and with a feather fan in the other, facing the Father Commissary, without ceasing made gestures and whistles to the beat of the teponastle [log drum] that another Indian near the litter was playing among many who sang to the same sound, making much noise and giving shrill whistles; six Indians carried this litter and tower on their shoulders, and even these also went dancing and singing, doing steps and the same dancing tricks as the others, to the sound of the same teponastle; it was sightly that tower, very tall and was visible from afar by being so tall and painted. This dance and device in that language is called zono and is what was used in ancient times (Clendinnen Reference Clendinnen2003: 159–60).

Thus, while the monuments and lintels memorialise a narrow perspective of performative acts, it is clear that many others also bore the weight of rituals.

Beyond the ruler's body, common corvée labourers bore the burden of carrying heavy monuments to commemorate period-endings, and heavy construction materials (e.g. stone, wood, water) for the building of ceremonial architecture. Energetic studies often consider weight and the quantitative scaling of these burdens (Abrams Reference Abrams1994), although the implications of such studies have often been used to measure the power and status of political officials and household heads, rather than to consider the experiences of those who did the heavy lifting. And, for some, the weight of everyday items, such as firewood and water (Morehart & Helmke Reference Morehart and Helmke2008), were heavy burdens that went without recognition or ceremony. Women at the height of their pregnancy often carry approximately 11.3kg of extra weight, and young Maya girls today are known to carry 11.3–13.5kg of water (including the weight of the ceramic jar) in their daily trips from river to house (Reina & Hill Reference Reina and Hill1978: 227, 240–43). These weights are not dissimilar from the weight-burden estimate placed upon the jade ornamented ruler on Ucanal stela 4.

Conclusions

The weight of Classic Maya rituals was—both literally and metaphorically—substantial. Maya lords ornamented themselves with finely carved but extremely heavy jade ornaments as they danced and conducted rites within public spaces. A comparison of both provenanced and unprovenanced jade head pendants carved in the round indicates that two major size categories existed. The larger of these head pendants, including the jade head pendant from Ucanal, were probably belt ornaments. These and other jade body ornaments symbolised the prestige and rank of titled elites along with the responsibilities of political office. Jade ornaments were, however, more than just a metaphor for the burdens of rank and office; they literally weighed elite personages down and made their dancing and performances an embodied part of ritual work. As stone monuments and other official media focus solely on the ritual work of royals and nobles, it is easy to forget the labour of non-royal peoples. Thus, by critically evaluating weight, we find that the weight carried by the most privileged of society may have paled in comparison to those who literally carried these individuals and their finery—or may have been comparable to the burdens carried by common people on an everyday basis. Perhaps it was this irony that led to the cessation in the production of elaborate jade head pendants throughout the Maya area at the end of the Classic period.

Acknowledgements

This article was first formulated as part of a talk by C. Halperin at the 2017 University of Texas Sibley Conference organised by Julia Guernsey and Cathy Costin. The article benefited from this creative venue, allowing it to consider the topic of scaling up and down with weight, and C. Halperin is grateful for all the comments by the participants. We also would like to thank the comments and helpful suggestions of Stephen Houston, Bryan Just and Brigette Kovacevich; all errors are, of course, our own. Research by the Proyecto Arquólogico Ucanal was funded by a grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the National Geographic Society, Waitt Foundation. We thank our Guatemalan co-director, José Luis Garrido, for his support as well as project excavators and personnel from San José, Barrio Nuevo San José, La Blanca and Pichilito II for their expertise and substantial heavy lifting of earth and stone while in the field. We are grateful to the Departmento de Monumentos Prehistoricos y Coloniales from the Ministerio de Culture y Deportes in Guatemala for their support and permission to work at Ucanal.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.65