Tracing writing on Cyprus

Cypro-Minoan writing, a syllabic script, was used on the island of Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1050 BC). Despite several attempts at decipherment, the language behind the script remains unidentified (Masson Reference Masson1974; Olivier Reference Olivier2007; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012). This conclusion makes all inferences on possible readings of texts highly tentative. Nonetheless, a close analysis of the inscriptions, and patterns of repeated sign-sequences, can point towards possible interpretations of subject matter in some of the texts, allowing a contextual understanding of how the script was used. It is attested at all urban sites in Late Bronze Age (LBA) Cyprus and the city of Ugarit in Syria; its period of maximum expansion can be assigned to the last centuries of the second millennium BC, until the very end of the LBA. The script is also found on a vast array of objects, metal vessels, clay balls, ivory objects and ceramics, usually represented by short inscriptions of a few sign-sequences.

The brevity of the texts, and the fact that the whole corpus comprises no more than 250 inscriptions, hinder all attempts at decipherment, but much can be inferred even without being able to read the script closely. Subject matter can be evinced with plausibility, if not with the full cogency of a decipherment. For instance, inscriptions on small spherical clay balls and ivory objects may record the names of individuals (Masson Reference Masson1974; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012; Steele Reference Steele2014). Equally, administrative texts are few and far between but still represented to a limited extent (Smith Reference Smith and Smith2002). Furthermore, the entire corpus of clay tablets in Cypro-Minoan comprises only ten examples, six from Cyprus (Karageorghis & Kanta Reference Karageorghis and Kanta2014: 110) and four from Ugarit (Yon Reference Yon1999). The presence of tablets, in addition to other objects inscribed at Ugarit strongly suggests that a special relationship existed between Enkomi and Ugarit—two ports that face each other across 160km of sea and that were important hubs in the trade of both copper and tin (Figure 1; Bell Reference Bell, Kassianidou and Papasavvas2012).

Figure 1. The Eastern Mediterranean, showing locations mentioned in the text.

Attempting to ‘read without deciphering’, we consider the possibility that one of the primary concerns of LBA Cypriots—the production and maritime trade of copper metal in ingot form—may have left tangible traces in the epigraphic evidence that can be detected with a degree of confidence. We therefore analyse a series of almost identical texts that recur on different types of objects from different locations where Cypro-Minoan is attested. The hypothesis we offer is that copper exported from the island as a primary product from Cypriot ores (as opposed to recycled metal) may have borne a recognisable brand through inscriptions denoting its quality on miniature ingots (which may also have acted as samples), as well as on clay labels.

Wengrow (Reference Wengrow2008) recently investigated the role of commodity branding in prehistoric societies, and a growing body of work has consequently considered whether this concept is applicable to the production and consumption behaviours of pre-industrial societies (Bushnell Reference Bushnell2013). Prior to this, it was held that commodity branding was a phenomenon that arose from the economies of scale of the Industrial Revolution. Wengrow (Reference Wengrow2008) argued convincingly that early forms of commodity marking, such as sealing practices associated with the Urban Revolution in the fourth millennium BC, can shed light on the aspects such as quality, authenticity and ownership that are characteristics of modern brands when identifying mass-produced goods. Arguably, the LBA was a period when abundant supplies of copper from mainland sources were also available to the main customers of Cyprus around the Mediterranean Basin, and a distinguishing mark denoting quality would have been desirable.

Copper exports from Cyprus in the Late Bronze Age

The copper exports of Cyprus were crucial both to the island's prosperity during the LBA and its prominence in the widespread trading networks of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East. Textual references to the availability of Cypriot copper on the mainland date back to the eighteenth-century BC texts from Mari on the Euphrates, where one text refers to copper from the ‘mountain’ of Alashiya, the ancient name for Cyprus (T.361; Knapp Reference Knapp1996: 18; Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Kassianidou and Donnelly2001).

The discovery of archaeological evidence of copper extraction on Cyprus from this period was comparatively recent due to the destruction of ancient workings by continuous mining up to modern times. Politiko-Phorades, located in the northern Troodos foothills, was identified in 1996 as possibly being a primary smelting site. Subsequent excavations (Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Kassianidou and Donnelly2001) confirmed this, and radiocarbon dating, combined with well-stratified ceramics found in association with the metalwork, places Phorades in the early phase of the LBA (1650–1500 BC) (Knapp & Kassianidou Reference Knapp, Kassianidou and Yalçin2008).

The earliest evidence of metalworking at Enkomi comes from the Middle Cypriot III period (Stech Reference Stech, Muhly, Maddin and Karageorghis1982; Kassianidou Reference Kassianidou2013) in the so-called fortress area at the north of the site. This is the earliest evidence of metalworking from an urban site on Cyprus. Bronze-working was a major industry during the LBA, with this northernmost quarter containing the greatest concentration of metal workshops that span the entire occupation history of Enkomi, the earliest Middle Cypriot III layer being on bedrock (Dikaios Reference Dikaios1971: 499; Courtois Reference Courtois, Muhly, Maddin and Karageorghis1982). This is consistent in timescale with the textual references from Mari (Bell Reference Bell2006: 78).

Much of the copper shipped from the island was in the form of oxhide ingots (which have been found from southern France to Mesopotamia, and from the Danube to Thebes in Egypt), and lead isotope analyses of such ingots dating after 1400 BC are consistent with a Cypriot origin (Gale Reference Gale, Betancourt and Ferrence2011). Furthermore, not only do these ingots map to Cyprus, but specifically to the Apliki ore deposit in the north-eastern Troodos. Gale has also suggested that this mining area may have had a monopoly on providing copper for casting large oxhide ingots, while many copper-based artefacts from contemporaneous Cypriot sites were made from copper from other ore deposits around the Troodos. Perhaps Gale can be criticised for drawing conclusions on such specific origins for ingots (Pernicka Reference Pernicka, Roberts and Thornton2014), but the technique remains useful for recognising ore bodies generated at different times.

Many oxhide ingots carry marks, and scholars generally agree that these seem to resemble Cypro-Minoan more than other contemporaneous writing systems (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2013: 45). Kaiser has noted that of the sites known to have contained half ingots or fragments larger than this, at least 245 bear marks: approximately 58 per cent of the corpus. With few exceptions, however, these full-sized ingots do not bear marks that can unequivocally be identified as Cypro-Minoan.

Branding the miniature copper ingots

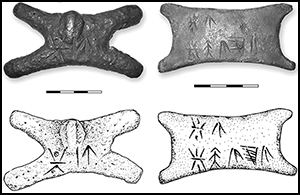

There are six miniature ingots from Enkomi and half of one from Mathiatis, four of which are inscribed in Cypro-Minoan (Figure 2). XRF spectrometry has demonstrated thatthey are all made of virtually pure copper, rather than bronze, and contain no trace of tin (Giumlia-Mair et al. Reference Giumlia-Mair, Kassianidou, Papasavvas, Betancourt and Ferrence2011).

Figure 2. The four inscribed miniature ingots from Enkomi, Cyprus, with their respective drawings (inv. nos. 53.2, 53.3, 1936-VI-19/1 and 1995, from top to bottom). Note that no drawing is available for no. 1995. Photograph adapted from Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012. Scales in cm.

Since the 1950s, the function of these miniature ingots has been consistently interpreted as votive (Catling Reference Catling and Schaeffer1971; Karageorghis & Masson Reference Karageorghis and Masson1971; Masson Reference Masson and Schaeffer1971; Knapp Reference Knapp1986; Papasavvas Reference Papasavvas, Lo Schiavo, Muhly, Maddin and Giumlia-Mair2009; Giumlia-Mair et al. Reference Giumlia-Mair, Kassianidou, Papasavvas, Betancourt and Ferrence2011; Kaiser Reference Kaiser2013), with inscribed specimens carrying dedications to deities. This was based on the assertion that the ingot symbolism and copper production were interpreted as connected with religious practices (see Catling Reference Catling and Schaeffer1971 for the Ingot God figurine), which came under the protection of gods worshipped in the sanctuaries of manufacturing cities (Knapp Reference Knapp1986). The association of the miniature ingots with a cult, at Enkomi at least, is, however, tenuous (Webb Reference Webb1999). Only two contexts can support a ritual association, albeit vague. The contexts in which the other specimens were found are unequivocally domestic. Their votive function is, therefore, to be questioned.

If the contextual association of the objects does not yield incontrovertible indication of their purpose, a close analysis of the texts on the inscribed ingots may help to advance possible inferences. This synergic perspective, one that combines archaeological and epigraphic evidence, is essential to developing the study of any undeciphered script. Indeed, this approach has met with remarkable success in recent times for ancient writing in general (e.g. Houston Reference Houston2004). Three examples of miniature ingots from Enkomi bear recognisable inscriptions (inv. 1936/Vi-19/1, ##174 in Olivier Reference Olivier2007 and inv. 53.2, ##175, inv. 53.3 ##176 in Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012), that is, inscriptions of two or more consecutive associated signs diagnostic of the Cypro-Minoan repertoire. A fourth example from Enkomi, inv. 1995 (Dikaios Reference Dikaios1971: 691; Giumlia-Mair et al. Reference Giumlia-Mair, Kassianidou, Papasavvas, Betancourt and Ferrence2011: 14, fig. 2.2) bears only one sign, and thus cannot be taken to be an inscription stricto sensu (which explains why it was excluded from the extant corpora of Cypro-Minoan texts). The single sign on this specimen can, however, be recognised as a rotated sign 23 in the Cypro-Minoan signary, which corresponds in shape to

![]() . This sign happens to be attested on the other miniature ingots, also in an isolated position. As can be observed in Figure 3, the pattern of epigraphic regularity on the first three ingots is interesting.

. This sign happens to be attested on the other miniature ingots, also in an isolated position. As can be observed in Figure 3, the pattern of epigraphic regularity on the first three ingots is interesting.

Figure 3. Cypro-Minoan texts inscribed on the miniature ingots from Enkomi and on a clay label from Ugarit-Ras Shamra.

Ingots ##174 and ##176 share the same signs, separated by the usual division marker, which singles out sign-sequences. Single signs are regularly attested in the Cypro-Minoan corpus, most notably on a large number of inscribed clay balls and other high-status paraphernalia, such as ivory objects and metal bowls (see Figure 4 for a full list).

Figure 4. Isolated signs in the Cypro-Minoan texts.

Ingot ##175 bears a sequence of 1+1 words, with the first sequence identical to those attested on the other two ingots, albeit without the division marker. The first two signs on this ingot are spaced out as equally as the rest of the signs in the remainder of the inscription, with no evident gap between them. This implies that we cannot argue that a separating space was intended between sign 102 (

![]() ) and sign 23 (

) and sign 23 (

![]() ), in substitution for the vertical dividing bar. Are we, therefore, to assume that the same sequence was recorded on the three ingots, or, conversely, that the beginning of the text on ##175 is semantically different? There is evidence to support the former hypothesis.

), in substitution for the vertical dividing bar. Are we, therefore, to assume that the same sequence was recorded on the three ingots, or, conversely, that the beginning of the text on ##175 is semantically different? There is evidence to support the former hypothesis.

It is worth mentioning that the reading of the inscriptions on the ingots, and their exact function, are controversial. It has been stated that:

the first sign on the three miniature ingots from Enkomi coincides with the second sign, after a vertical bar, inscribed on the two bronze ring-stands from Myrtou-Pigades [. . .] These artifacts were found in a sanctuary, so their inscriptions are most probably dedicatory. This can be taken as indirect evidence for the votive character of the miniature ingots (Giumlia-Mair et al. Reference Giumlia-Mair, Kassianidou, Papasavvas, Betancourt and Ferrence2011: 17).

We can claim with a certain degree of confidence that this is not the case, as the two ring-stands from Myrtou-Pigades bear different inscriptions from the ones incised on the ingots (##184 and ##185 in Olivier Reference Olivier2007: 257–58 and Ferrara Reference Ferrara2013: 93–94, 230–31). The inscriptions on the two ring-stands are identical, namely

![]() and

and

![]() (038-104-101). Noteworthy is the fact that the second ring-stand, ##185, does not have the separation marker seen in the first, which, again, offers an intriguing parallel for the missing separator on ingot ##175, and further reinforces the possibility that typologically identical objects with almost identical texts, distinguished only by the presence or absence of a word-divider, are intended to bear the same message.

(038-104-101). Noteworthy is the fact that the second ring-stand, ##185, does not have the separation marker seen in the first, which, again, offers an intriguing parallel for the missing separator on ingot ##175, and further reinforces the possibility that typologically identical objects with almost identical texts, distinguished only by the presence or absence of a word-divider, are intended to bear the same message.

Despite the regularity in indicating word-division in Cypro-Minoan, several instances of missing division markers can be observed. Figure 4 records only a few, but more can be detected and restored throughout the corpus (see ##042, ##054, ##078, ##185; Olivier Reference Olivier2007). Therefore, by analogy, it would not be counter-intuitive to venture into restoring a separation marker between the first two signs on ##175. This would harmonise the epigraphic evidence on the ingots and help to make sense of their significance as a set. But, as will become apparent below, a striking parallel strengthens this inference significantly.

Traces of copper from Ugarit

As already mentioned, Ugarit in Syria is the principal overseas find-spot of Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, where eight examples have been found. The mini-corpus of texts includesfour tablets that were found in, or in the proximity of, houses of merchants known from Ugaritic and Akkadian archives (van Soldt Reference van Soldt and Bongenaar2000). The house of Urtenu yielded a label inscribed in Cypro-Minoan (##210, RS 94.2328; Yon Reference Yon1999; Olivier Reference Olivier2007; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2013). As shown in Figures 3 and 5, the text on the label is identical to the first sequence found on miniature ingot ##175.

Figure 5. Cypro-Minoan label found at Ugarit (RS 94.2328), ##210. Photograph adapted from Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012. Scale in cm.

Similarly, on this object, the expected division marker between the two signs,

![]() (102-23), is missing, although in its place there is an evident gap, with signs appearing intentionally spaced out on the label. Therefore, we can postulate that they may either have been separated by a division marker, which could be restored, or else that they were clearly recognisable as two distinct signs that were not strictly consecutive (that is, part of one sign-sequence). Typologically, the label does not fit into the classes of labels normally found at Ugarit (van Soldt Reference van Soldt1990), and the likelihood is that it was not inscribed in Syria but sent from Cyprus, attached to, or identifying, commodities intended for export. This can be inferred from the characteristics of the signs, which resemble more closely the Cypro-Minoanvarieties found on Cyprus than the highly idiosyncratic writing on the remainder of the inscriptions from Ugarit, which were probably written in situ by scribes not particularly familiar with Cypriot writing (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012).

(102-23), is missing, although in its place there is an evident gap, with signs appearing intentionally spaced out on the label. Therefore, we can postulate that they may either have been separated by a division marker, which could be restored, or else that they were clearly recognisable as two distinct signs that were not strictly consecutive (that is, part of one sign-sequence). Typologically, the label does not fit into the classes of labels normally found at Ugarit (van Soldt Reference van Soldt1990), and the likelihood is that it was not inscribed in Syria but sent from Cyprus, attached to, or identifying, commodities intended for export. This can be inferred from the characteristics of the signs, which resemble more closely the Cypro-Minoanvarieties found on Cyprus than the highly idiosyncratic writing on the remainder of the inscriptions from Ugarit, which were probably written in situ by scribes not particularly familiar with Cypriot writing (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012).

There is another such label (##211, RS. 99.2014, quoted in passing, in Yon Reference Yon1999; Olivier Reference Olivier2007; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2013), which is very similar in format and sign-shapes to label ##210, although the inscription is different, as it probably reads òœ§ (052-107-064, the text is damaged). Although the quantity of evidence is limited, a plausible explanation is that such labels fulfilled the same function as marks of direct Cypriot provenance.

Could the (almost) identical texts outlined in Figure 3 refer to copper in some way? And if so, can we take the argument a step further and narrow down the possible message carried by the inscriptions? Can the texts themselves help venture further into the significance of the miniature ingots as exclusive, prerogative objects produced by the Cypriots? Before we turn to these admittedly challenging questions, a lexical excursus may inform our investigation.

Philological traces of metals

Semitic languages, such as Ugaritic and Hebrew, share the trait of not adopting a lexical distinction between ‘copper’ and ‘bronze’. This can be extended to Mycenaean and historical Greek use, where ka-ko and χαλκός indicate both materials interchangeably (despite scholarly resistance in accepting the fact that ka-ko refers to copper; see Muhly Reference Muhly, Lo Schiavo, Muhly, Maddin and Giumlia-Mair2009). This applies to Akkadian as well, but the terminology is more complex, as Akkadian distinguishes between copper (w)erû and bronze siparru, but the terms do intersect (Zaccagnini Reference Zaccagnini1971); it further applies to Egyptian, where the word for copper and that for bronze coexisted. It is interesting to note that, lexically, the terms for bronze are late or restricted to special regions. Incidentally, ka-ko points to a non-Indo-European source, as Proto Indo-European does not tolerate a root with a voiceless and an aspirated stop. In Hittite, the Sumerogram ZABAR is used, but the phonetic equivalent is unknown (Mallory & Adams Reference Mallory and Adams1997). That potential confusion engendered by this lack of differentiation may arise in the early texts is hardly surprising, given that copper and bronze are not easily distinguished by eye (Moorey Reference Moorey1994; Muhly Reference Muhly, Lo Schiavo, Muhly, Maddin and Giumlia-Mair2009). This point proves relevant for our purposes.

Although we cannot speculate on the language(s) spoken by the LBA Cypriots, it seems reasonable to assume that a word for copper was in common usage, and possibly written down in Cypro-Minoan. It has been suggested that the name of the island as ‘Kypros’ may descend from Hurrian *kab/p (kabali), meaning ‘copper’ (Knapp Reference Knapp1996: 11–13; Duhoux Reference Duhoux2003), which later, through Latin cuprium ‘Cypriot’, came to mean the raw material found on Cyprus. In this case, the word for copper would have no correlation with the name of the island as it was known during the Bronze Age, a name that was transmitted through sources that are not directly Cypriot. In the Amarna letters and in Ugarit correspondence of the LBA, both written in Akkadian cuneiform, Cyprus is invariably referred to as Alashiya (Knapp Reference Knapp1996).

Turning to the inscriptions on the ingots and on the Ugarit label, if we accept that the first two signs on them record the same message, we could speculate on its meaning in the broader context of the functionality of the ingots. The ingots are Cypriot and are made of refined copper—more so than even the very pure copper of full-sized oxhide ingots (Kassianidou Reference Kassianidou, Lo Schiavo, Muhly, Maddin and Giumlia-Mair2009; Giumlia-Mair et al. Reference Giumlia-Mair, Kassianidou, Papasavvas, Betancourt and Ferrence2011). This suggests a symbolic importance that had close ties with the production process and demand for objects containing pure copper coming from the island. Cypriot producers would have wished to make such a distinction clear in order to obtain the highest value when dealing with potential customers. To achieve this, what better strategy could have been adopted than marking provenance and quality on the ingots? Could this be an early form of brand or trademark?

It is instructive to consider how industrial metals are sold nowadays on the London Metal Exchange. These metals are priced and delivered according to their ‘brand’, defined as a mark or name identifying the smelter, refiner, semi-fabricator or steelworks that produced the metal. In primary metals (those that have been smelted directly from ore, rather than from recycled scrap), this is often associated with a full chemical analysis.

Returning to the inscriptions, several analyses of the palaeography of the Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, note that sign 102

![]() invariably appears in initial position within a sign-sequence (Olivier Reference Olivier2007: 474–76; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012, Appendix 5). In an open syllable internal structure, as is the case for Cypro-Minoan, such a characteristic highlights the presence of a single vowel being recorded. It has been suggested that sign 102

invariably appears in initial position within a sign-sequence (Olivier Reference Olivier2007: 474–76; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012, Appendix 5). In an open syllable internal structure, as is the case for Cypro-Minoan, such a characteristic highlights the presence of a single vowel being recorded. It has been suggested that sign 102

![]() , being the sign most frequently found in initial position, could record the vowel /a/ (Masson Reference Masson1974). This sign appears very similar to the sign used for the same vowel both in Linear B,

, being the sign most frequently found in initial position, could record the vowel /a/ (Masson Reference Masson1974). This sign appears very similar to the sign used for the same vowel both in Linear B,

![]() , and in the Cypriot Syllabary of the first millennium,

, and in the Cypriot Syllabary of the first millennium,

![]() . Could this point to a reference to Alashiya (Cyprus), abbreviated at the beginning, to indicate the origin of the object? And further on, the second syllable recorded on the ingots and the label from Ugarit, sign 23

. Could this point to a reference to Alashiya (Cyprus), abbreviated at the beginning, to indicate the origin of the object? And further on, the second syllable recorded on the ingots and the label from Ugarit, sign 23

![]() , is similar to the sign for the syllable /ti/ in the Linear B script,

, is similar to the sign for the syllable /ti/ in the Linear B script,

![]() . The sign for the same syllable in the Cypriot Syllabary,

. The sign for the same syllable in the Cypriot Syllabary,

![]() , could be a local Cypriot development, in direct trajectory from Cypro-Minoan. If this is correct, then a case could be made for another abbreviation, for the Cypriot word for ‘copper’, a word possibly starting with /ti/. Could this be an adapted loan of the Ugaritic word ṯlṯ? The term would, thus, have been modified again, using just the beginning of the word.

, could be a local Cypriot development, in direct trajectory from Cypro-Minoan. If this is correct, then a case could be made for another abbreviation, for the Cypriot word for ‘copper’, a word possibly starting with /ti/. Could this be an adapted loan of the Ugaritic word ṯlṯ? The term would, thus, have been modified again, using just the beginning of the word.

Caution must be exercised when proposing such hypotheses before they can be tested against more substantial attestations. As is well known, similarity in the shape of signs is never an unassailable method for establishing sound values. By this line of reasoning, we could claim that the similarities in the signs for the syllable /ti/ in known scripts may not point to the same phonetic realisation in homomorphic sign 23

![]() . Moreover, the interpretation we have just proposed should work for all other attestations of the isolated sign 23

. Moreover, the interpretation we have just proposed should work for all other attestations of the isolated sign 23

![]() . This becomes more difficult to prove if such occurrences are on objects that may not have anything to do with copper specifically (see the same attestations of sign 102

. This becomes more difficult to prove if such occurrences are on objects that may not have anything to do with copper specifically (see the same attestations of sign 102

![]() and sign 23

and sign 23

![]() , found in isolated position on the ivory pipe ##161, Figure 4). We cannot, therefore, rule out the possibility that both signs have been used as abbreviations for other words, or that they may be logograms. We may never discover the word for ‘copper’ in ancient Cypriot, but the fact that the material of which the miniature ingots are made would be part of the message to be conveyed on them, as a trademark and precise assertion of its purity, remains a tantalising proposition. If, as postulated above, a rotated sign 23

, found in isolated position on the ivory pipe ##161, Figure 4). We cannot, therefore, rule out the possibility that both signs have been used as abbreviations for other words, or that they may be logograms. We may never discover the word for ‘copper’ in ancient Cypriot, but the fact that the material of which the miniature ingots are made would be part of the message to be conveyed on them, as a trademark and precise assertion of its purity, remains a tantalising proposition. If, as postulated above, a rotated sign 23

![]() is also attested on miniature ingot 1995, then all specimens of the miniature ingots bear the same ‘brand’, and this congruence of signs in the whole repertoire of pure copper objects points to the same statement: these objects are made of ‘pure Cypriot copper’.

is also attested on miniature ingot 1995, then all specimens of the miniature ingots bear the same ‘brand’, and this congruence of signs in the whole repertoire of pure copper objects points to the same statement: these objects are made of ‘pure Cypriot copper’.

With this in mind, we would like to propose a new interpretation that avoids the necessity to invoke a votive function for the ingots and a dedicatory one for their inscriptions. These objects may not have a practical use as miniature versions of the full-scale functional objects they mimic, but they do have an intrinsically symbolic one. The function of pure copper is never utilitarian. But in selling it abroad, Cypriots must have been aware of how marking its exclusive quality ‘as 100 per cent copper’ would differentiate it from similar objects, which the naked eye could mistake for bronze. Put in modern terms, marking the miniature ingots made of Cypriot copper branded them as pure and created a unique selling proposition. Could the marked miniature ingots have acted as a specific and exclusive form of sample material for Cypriot intermediaries to show to the customers who acquired the tonnes of full-sized oxhide ingots that were exported from the island during the LBA?

Marking copper in the Mediterranean

Now that a reading of these inscriptions, albeit speculative, has been proposed, it may be worth integrating it with the more general activity of marking normal-sized oxhide and bun ingots. Marks on these typologies of objects are impressed, incised or chiselled, and are attested on at least half of the corpus of oxhide ingots from several sites in the Mediterranean, in notable quantities from the Uluburun and Cape Gelidonya shipwrecks. In analysing the morphology of these marks, it becomes apparent that their relation to the Cypro-Minoan script is tenuous, despite a general tendency to assume it as a working hypothesis (Amadasi Guzzo Reference Amadasi Guzzo, Lo Schiavo, Muhly, Maddin and Giumlia-Mair2009; Kaiser Reference Kaiser2013).

As already brought to light by Hirschfeld in relation to the practice of marking pottery, the shapes of the signs present on both ceramics and ingots, which are to an extent shared, are basic and pervasive in all marking systems of the Mediterranean, defined as ‘simple marks that cross cultural boundaries’ (Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1999: 109, 249). Their relation to language notation is problematic, and we should discount any intentional recording of morphological features, even in abbreviated form. As a viable parallel, it can be noted that Greek lead ingots from Laurion were often stamped with non-alphabetic trademarks (Bass et al. Reference Bass, Throckmorton, Du Plat Taylor, Hennessy, Shulman and Buchholz1967). Therefore, it is worth stressing the fact that the marks on the normal-sized ingots have nothing to do with Cypro-Minoan or with any script that records language.

If their correlation to proper writing is to be discounted, the interpretation of their function remains equally obscure. The scholarship on the topic has grappled with this problem without reaching cogent results (Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1999; Kassianidou Reference Kassianidou, Giumlia-Mair and Schiavo2003; Amadasi Guzzo Reference Amadasi Guzzo, Lo Schiavo, Muhly, Maddin and Giumlia-Mair2009; Kaiser Reference Kaiser2013). The marks may have been used to record processes, such as shipping information, and may have been related to the producers, harbours of departure, addresses for delivery, etc. (Kaiser Reference Kaiser2013). Some of them may also point to the source of metal, be it a mine, mine-owner, state official or guild. This has been proposed for the marks that Bass calls ‘primary’, namely those impressed into the metal while it was soft (Bass et al. Reference Bass, Throckmorton, Du Plat Taylor, Hennessy, Shulman and Buchholz1967: 72), as opposed to those incised at a later stage, post-manufacture.

This brief excursus on oxhide-ingot marks is helpful because it can shed more light on the significance of the miniature ingots. From a macro perspective, if the marks indicate manufacture, whether a stage in the production, shipping or delivery, the inscriptions on the miniature specimens may be more suggestive, and recognisable, in the statements they make, because they are made in a specific language and script. They may be, in other words, testimonials of value and provenance of the material of which they are made. In this light, the miniature ingots in themselves will act as samples, and the inscriptions as reinforcing statements.

It is interesting to note that ingots in Roman times bore more information than any other ancient body of such objects. Inscriptions on lead ‘pigs’ and ‘bun-shaped’ copper ingots from Roman Britain and Gaul were stamped with personal names or with the letters socio(rum) Romae. Cast mould marks on lead ingots read socior(um) Lut(udarensium) Brit(annicum) ex arg(entariis), i.e. ‘British lead from the silver mines of the socii at Lutudarum’, which is a Derbyshire lead-mining area (Hirt Reference Hirt2010). Most mould marks on lead ingots dated to the Principate provide the personal names of individuals, in abbreviated form, as do those on ingots found on shipwrecks from the Balearics, southern Gaul and Corsica (Domergue Reference Domergue1990). For the Roman ingots, the application of cold stamps, holes and numerals can be explained, but the role of the individuals is more difficult to identify. There tends to be a genitive of the personal name, possibly a possessive indicating ownership. The origin is indicated, either by adjective or by preposition. These may name the initial owner of the ingot at the time it was cast (Hirt Reference Hirt2010: 283). Ingots were, in effect, personalised.

This parallel could explain a section of one of the inscriptions of the ingots that we have not yet treated, the sign-sequence on the Enkomi ingot no. 53.3, ##175. This sequence,

![]() (102-?-23-?-23) is only attested here. Two of the signs (the second and fourth) are also only attested here. What is significant is the fact that the last sign appears in word-final position often in the corpus of inscriptions. It has been suggested elsewhere that it may function as a possessive suffix (Masson Reference Masson1974; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012). If this is correct, it would point to the possibility that a personal name may be recorded, in addition to and after the abbreviated signs denoting origin and purity of material.

(102-?-23-?-23) is only attested here. Two of the signs (the second and fourth) are also only attested here. What is significant is the fact that the last sign appears in word-final position often in the corpus of inscriptions. It has been suggested elsewhere that it may function as a possessive suffix (Masson Reference Masson1974; Ferrara Reference Ferrara2012). If this is correct, it would point to the possibility that a personal name may be recorded, in addition to and after the abbreviated signs denoting origin and purity of material.

Writing as ‘branding’

Overall, the miniature ingots, together with the inscriptions, appear to function within a value system that understands the desirability of pure Cypriot copper. In contrast to what has been suggested in the past, the likelihood is that they did not represent votive religious paraphernalia, and the texts they bear need not have been dedications to unidentifiable deities. The admittedly circumstantial evidence we have presented here strongly suggests that the miniature ingots functioned as branded tokens of quality and as samples of original production. In this capacity, they assisted in the process of convincing consumers of the desirability of acquiring pure Cypriot copper.

We cannot speculate that the miniature ingots were intended to be sold, but the label bearing the same inscription found abroad probably arrived at its destination through commerce. Consumers will consider purity, quality and provenance as factors when selecting commodities, and the wider cultural value of pure Cypriot copper was recognised throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. All full-sized oxhide ingots after 1400 BC are argued to be consistent with production from Cypriot ores. By the end of the Late Bronze Age, this trade became commoditised. The placement of specific writing on individual, and individualised, objects generated an element of added value for further exotic appeal. It is not coincidental, perhaps, that Cypro-Minoan was chosen as the script to carry this message.

Unlike tin, copper is relatively common in nature, and marking Cypriot copper with an attestation of its quality and provenance would differentiate the commodity, enabling Cypriot producers and their intermediaries to attain the best value for their metal. Last, but not least, in an age when recycling of copper and bronze was well known, might these marks also have indicated that the copper was the product of primary smelting of ore—directly from the mine—in the way that primary metal is still marked and assayed today?