Introduction

The ‘Murujuga: Dynamics of the Dreaming’ project examines the archaeology of the Dampier Archipelago, also known by its Aboriginal name of Murujuga, located off the north-west coast of Australia (Figure 1). Excavation has recovered evidence for Pleistocene and Holocene occupation, which contextualises the long-term production of Aboriginal rock engravings (petroglyphs) across the archipelago (Mulvaney Reference Mulvaney2015; McDonald & Berry Reference McDonald and Berry2016). This multi-layered archaeological landscape records a deep time set of human responses to the changing landscape: in the Pleistocene, when the coastline was 160 km distant from its present location; at the Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene transition, when the landscape was transformed into a series of coastal hills; and in the Mid Holocene, by which time the hills had become islands. The most recent part of this deep time sequence is represented by two newly discovered nineteenth-century inscriptions made by American whalers. These two inscriptions provide the first evidence for non-Aboriginal memorialisation practices in the Dampier Archipelago. This article describes the discovery of the inscriptions, attributed to the crews of the North American whaling ships Connecticut, in 1842, and Delta, in 1849, and provides archaeological and historical evidence for the significance of the events surrounding them.

Figure 1. Map of the Dampier Archipelago showing the locations of historical inscriptions on Rosemary and West Lewis Islands (map by Ken Mulvaney).

We refer to these two marking events as inscriptions—contra the definition used by Clarke and Frederick (Reference Clarke and Frederick2016: 524), who understand inscriptions to be “more institutionalised than graffiti, and requiring greater levels of skills and planning”. Instead, we follow the work of Alison Bashford et al. (Reference Bashford, Hobbins, Clarke and Frederick2016: 18), who argue that

the historical geography of memorialising and commemoration operates across a continuum, from highly orchestrated state endeavours to intensely private individual mark-making practices […] The memorialising of lives, deaths, and events in landscapes can be authorised, official, and highly regulated, or spontaneous, unauthorised, and even anti-authoritarian.

With this memorialisation continuum in mind, we explore the narrative content of the whalers’ inscriptions. Do they represent “a trace of trespass, an act of usurpation [or] […] the colonial reordering of space” (Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke and Frederick2016: 524); or are they the spontaneous acts of individuals responding to the foreign antipodean natural beauty and already richly inscribed landscape of Murujuga?

The Dampier Archipelago was home to the Yaburara people (Tindale Reference Tindale1974). The earliest explorers and naturalists to make observations and collect scientific specimens here were William Dampier in 1699 and Phillip Parker King in 1818—the latter was the first European to document encounters with the Yaburara. Permanent European colonisation of this part of Australia began much later, in the early 1860s, with an influx of sheep farmers and pearlers. For the Yaburara, this colonisation was catastrophic. In 1868, a series of confrontations between white settlers and the Yaburara around Flying Foam Passage in the Dampier Archipelago—at that time the centre for the North West pearlshell fishery—resulted in many deaths. The Yaburara had retaliated against sexual assaults by the pearlers, killing a white police officer and his aide. In the ensuing violence, up to 60 Yaburara were murdered. The subsequent confrontations lasted several weeks and are known collectively as the Flying Foam Massacre (Gara Reference Gara and Smith1983; Gribble Reference Gribble1987; Paterson & Gregory Reference Paterson and Gregory2015). As a result of this violent history, there are few oral and documentary accounts of Yaburara life relating to the archipelago.

An overlooked aspect of early North West Australian contact history is the whaling that took place in the ‘New Holland Ground’, located off the Indian and Southern Ocean coasts of Western Australia. Throughout the nineteenth century, American, British, French and colonial Australian whaling ships plied these waters. American vessels were successful at a time when the British colony at Swan River, founded in 1829 and now known as Perth, was in its infancy. In 1840, for example, when the HMS Beagle visited Perth, John Lort Stokes was amazed to “count as many as thirteen American whalers at anchor” (Stokes Reference Stokes2006 [1846]: 115–16). Colonial port records, newspapers, whaling ship logbooks and American shipping records provide the main sources of data for these voyages.

Comparatively, early visits by foreign whalers to the shores of North West Australia are poorly documented, due to the absence of any British colonial activity in the area until the 1860s. Surviving ship logbooks do, however, detail the whalers Kingston of London and the North American Ann and Hope visiting the Dampier Archipelago as early as 1801—many decades before British colonisation. The heyday of whaling activities around Rosemary Island (named by Dampier) appears to date to between the 1840s and 1860s (Wace & Lovett Reference Wace and Lovett1973: 13; Langdon Reference Langdon1978, Reference Langdon1984; Gibbs Reference Gibbs2010: 368; Paterson Reference Paterson2006).

Whaling ships followed migrating herds of humpback whales along the coast and fished the offshore grounds for sperm whales. They also undertook ship-based bay whaling, anchoring in protected bays for up to three months (Gibbs Reference Gibbs2010). Knowledge concerning safe anchorages, hazards and local resources probably circulated amongst ships’ crews. Extant historical records, however, contain no mention of interaction with local Aboriginal people, although they do chronicle the types of activities that the whalers undertook (besides whale hunting).

The Connecticut inscriptions on Rosemary Island

Rosemary Island is located on the outer north-western part of the archipelago (Figure 1). Relatively small in size (approximately 5 × 3km), the island rises to only 65m asl, and has reliable water only after rain. The archaeological record demonstrates a limited Late Pleistocene human presence. This was followed by more intensive use of this landscape during the Early Holocene, connected with rising sea levels but prior to insulation by the Mid Holocene (McDonald & Berry Reference McDonald and Berry2016).

The Connecticut inscription is located on a high rocky ridgeline overlooking the interior passage between Rosemary and Malus Islands. This ridgeline, which runs for several kilometres along the edge of the island, would have offered an ideal vantage point for whale observation (Figures 1–2). Indeed, it had already been used for millennia by Aboriginal people for its views over the seascape below. This is evidenced by more than 265 rock art panels, over 70 standing stones and the extensive quarrying of the fine-grained basalt bedrock for tool-stone production. More than 800 recorded Aboriginal rock art motifs in this area include turtles, bird tracks, anthropomorphs and 81 cross-hatched ‘grid’ motifs (Table 1). The dominant engraving techniques are scratching, abrading or a combination of the two; pecking is rare. The relatively soft basalt bedrock here seems to determine the character of the mark-making (i.e. the engraving techniques) used by generations of Indigenous artists; this technique was similarly employed by the whalers.

Figure 2. Viewscape provided from each inscription's locale: top) Rosemary Island; bottom) West Lewis Island (images from the Centre for Rock Art Research + Management (CRAR+M) database.

Table 1. Rosemary Island area 3: motif techniques and subject choices.

* Combined abraded/incised/scratched/gouged.

¥ included pecked and pecked + gouged.

The Connecticut inscriptions are superimposed over earlier grid motifs of unknown meaning (Figure 3). Our initial field observations suggested that the whaling inscription was, in turn, itself covered by the engraving of a more recent Indigenous grid, perhaps a Yaburara response or act of resistance against the newcomers and their marks.

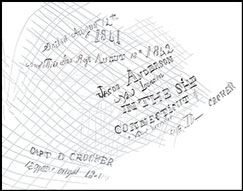

Figure 3. The Connecticut inscriptions, Rosemary Island, showing the panel (left) and tracing of the inscription (right) (images from the CRAR+M database).

The Connecticut inscription can be read as follows (‘?’ indicates illegible or unclear characters, square brackets indicate editorial suggestions):

Sailed August 12th

1841

And This Was Right? [written] August 18th 1842

JACOB ANDERSON

New London

IN THE SHP

CONNECTICUT of

New London

cpt D - CROKER

CAPT D CROCKER

12 mths out? 18[4]1

Examination of the lettering suggests that the inscription was created with different tools when compared to the earlier petroglyphs. The underlying Aboriginal grid motifs were engraved with a blunt object—presumably of stone—which created lines with ‘U-shaped’ sections. In contrast, the cross-sections of the engraved letters and numbers of the historical inscription are much narrower and have a sharper profile, presumably having been being made with a metal implement(s). The range of ‘penmanship’ (or hand strength) and the possible use of different tools suggests that more than one individual was involved in engraving the whaling inscription.

The relationship between the Aboriginal and historical marking events was clarified using image enhancement generated by the D-Stretch correlation plugin for ImageJ (Harman Reference Harman2013; Figure 4). Approximately 50 intersections between the letters and numbers of the historical inscription and the grid motifs were examined with a Dinolite™ digital microscope. In every instance, the narrower lines, presumably incised with metal tools, are superimposed over those lines believed to have been incised with stone implements. The historical inscription is clearly superimposed over all of the Yaburara grids (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The Connecticut inscriptions, showing the two different D-Stretch images: left) lds enhancement; right) lye enhancement (images from the CRAR+M database; for further details, see http://www.dstretch.com/AlgorithmDescription.html).

Figure 5. The Connecticut inscriptions: centre) D-Stretch (lye) image of panel; showing i) use of Dinolite; and ii–viii) instances where parts of the inscription superimpose the previously engraved grids. Insets are oriented so that the superimpositions align with the main image.

The inscription indicates that the Connecticut visited Rosemary Island on 18 August 1842, having left New London, Connecticut, on 12 August 1841 under the command of Captain D. Crocker. Documentary research has identified a record of the North American whaling ship Connecticut (a 398-ton bark) departing New London for the New Holland Ground on 12 June (not August; see below) 1841 with a crew of 26 under Captain Daniel Crocker. The Connecticut berthed at Fremantle—the harbour for Perth—on 30 September 1842: “Crocker, master, American whaler, 1000 brls. [barrels] black [oil], and 200 brls. Sperm oil, out 13 months” (The Perth Gazette and West Australian Journal 1842: 2). Evidently, the ship continued hunting, for when it returned to New London on 16 June 1843, it carried 1800 barrels of oil, having travelled via New Zealand and Cape Horn (Starbuck Reference Starbuck1878; Dickson Reference Dickson2007: 194; Mystic Seaport Museum 2017; National Maritime Digital Library 2017). The Connecticut’s logbook for the voyage has not survived. The anomaly between the historically recorded departure date and the inscription date may be an error either by the inscription's author(s), or in the historical records: the absence of the ship's logbook means that this cannot be resolved. It is plausible that the inscription event marked one year at sea and the crew's safe arrival on the far side of the earth.

We can assume that Jacob Anderson, named in the inscription, took part in the act of engraving. The use of two distinct styles—capitalised and cursive scripts—suggests, however, the presence of a second hand, perhaps that of the captain himself, Daniel Crocker. The historical records show that on the Connecticut’s initial departure from New London, Captain Crocker was 33 years old. Jacob Anderson was described as an 18-year-old seaman from New London, of “black complexion”, almost certainly an African-American sailor (New London crew lists 1803–1878 [2 April 2017]). Anderson's ethnicity was not unusual for whaling ship crews: by the end of the 1850s, one in six men aboard American whalers were recorded as being African-American (Farr Reference Farr1983: 162 & 166).

The superimposition of the historical inscription over an earlier set of markings requires comment. There are other suitably smooth and unmarked surfaces on the same rock surface, which could have equally been chosen; indeed, inscribing a legible script over these grids required considerably more skill than if a blank surface had been selected. Did the whalers leave their marks over earlier Aboriginal efforts as an act of trespass and usurpation? Or did they perceive that they were continuing a tradition of marking this coastal landscape? We interpret the Rosemary Island historical inscription to be similar to those on the other side of the continent at the Sydney Quarantine Station, where maritime travellers to Australian colonies were held from 1830 onwards. In their comprehensive study of these, Clarke and Frederick (Reference Clarke and Frederick2016: 521) describe them as representing “private declarations of presence, remembering and commemoration”. While this inscription is, however, also “highly spatially and temporally bounded” (Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke and Frederick2016: 521), this is not because of the institutional boundaries that constrained the makers, but rather because of the isolation of this place within the broad seascape of whaling.

The Delta inscriptions on West Lewis Island

West Lewis (Figure 1) is a moderately large island (approximately 10 × 3km) rising to 80m asl. It has a number of semi-permanent, spring-fed rock pools. The archaeological record demonstrates extensive evidence of Holocene occupation including petroglyphs. A rocky headland overlooking the channel between West Lewis and Enderby Islands (Figure 1) offers an ideal vantage point for whale spotting (Figure 2). Survey of the slopes and shoreline here have identified 83 Aboriginal rock art panels and 346 motifs (Table 2). These include depictions of marine animals, bird tracks, anthropomorphs and parallel line sets. Only six of these 152 geometric motifs are cross-hatched ‘grids’, as also found on Rosemary Island; a more common geometric motif on West Lewis is an incised fern (or barbed spear?) (n = 21). Amongst this extensive evidence for Aboriginal petroglyphs, survey has identified eight historical inscriptions—all interpreted in relation to the visit of the whaler Delta—located on a rock surface, again already richly marked with earlier Indigenous motifs.

Table 2. West Lewis Island area 5: motif techniques and subject choices.

* Combined abraded/incised/scratched/gouged.

¥ included pecked and pecked + gouged.

In this part of West Lewis, scratching is again the dominant engraving technique, although pecking is more common than in the vicinity of the Connecticut inscription (Table 2). As on Rosemary Island, the Delta whalers’ inscriptions use similar techniques to the majority of Aboriginal markings found locally. The clearest Delta inscription includes an incised anchor-and-rope motif, combined with a mixture of upper- and lowercase letters (see Figure 6). Three additional instances of the ship's name are found, all within a metre of each other. The day, month and year (12 July 1849) are indicated, with the year also being repeated (once clearly, the other abbreviated). Another element is the initials ‘BD’.

Figure 6. The Delta inscriptions, West Lewis Island, showing the motifs (left) and tracings of the inscriptions (right) (images from the CRAR+M database).

Documentary research links the inscriptions to the whaler Delta, registered in Greenport, New York. The Delta was built in Newbury, Massachusetts in 1831, and made 18 whaling voyages between 1832 and 1856, after which it was broken up. Its sixteenth voyage between October 1848 and June 1851 saw the ship visit the New Holland Ground under Captain David Weeks. The fact that the inscriptions do not record the Delta’s captain, but instead prominently incorporate the name of ‘J. Leek’—presumably a crew member—supports the interpretation that these engravings were spontaneous: made by crew members as informal, personal markers. Differences in the fonts and styles of the lettering (particularly the Ds and Es) show several hands at work. The placement of these inscriptions amongst already densely decorated panels, superimposed only over indeterminate pecked marks rather than over identifiable motifs, could be interpreted as an “act of usurpation” (Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke and Frederick2016: 524). As there was no eradication of earlier markings, and because of the similar size of their inscriptions and the engraving techniques used by the whalers, however, we suggest that this was a response by the new arrivals to the sheer profusion of Aboriginal markings. The location of the Delta inscriptions, high on the headland, is visible only to those who climb up to this place. Rather than a formal, public message for future visitors to the island, the inscriptions probably represent the whalers’ celebration and commemoration of having survived the voyage to the other side of the world. They are opportunistic memorialisations of the ship and the date of its visit, as well as the names or initials of its crew.

The logbook for this voyage survives and is held by the New Bedford Whaling Museum, Massachusetts. Whaling logbooks were typically written at the day's end, and detail weather conditions, whale sightings, hunting, kills and other significant events. Further evidence of the informal nature of the West Lewis inscriptions—but also highlighting their historical value—is the logbook entry for the date of the Delta inscriptions, which makes no mention of the crew going ashore. Instead, on 12 July 1849, it was recorded that the whaler Arab (of Fair Haven) was whaling in the area, and the Delta’s whale boats were out cruising and “saw several humpbacks going fast” (Captain Weeks, Delta logbook, 12 July 1849).

More generally, the logbook records that the crew would go ashore for a range of purposes: “liberty”; water (in two days, 30 April and 1 May 1849, they collected 180 barrels or 23 760L); hunting animals, with guns, including a “kangaroo” (probably a wallaby; 5 July 1849); and wood collection, to provide fuel for cooking and “trying out” whale blubber for oil on board the ship.

Typically, the Delta’s daily logbook entry finished with the line “So ends this day”. This appears as a constant—almost a mantra—recording the completion of an orderly and safe set of actions in the official log. Although the Delta’s logbook has missing pages, it provides sufficient information to reconstruct much of its voyage in the Indian Ocean (Figure 7). It further records that both Rosemary Island and the Lewis Islands provided anchorages, but before the discovery of the West Lewis inscriptions, we were unable to ‘place’ the participants of this voyage specifically on that island. While the motivation for this act of memorialisation cannot be fully appreciated, more broadly we observed that people record their presence as “textual expressions of one's self […] uniquely loaded with complex meanings of location, survival, biography, testimony and personal presence—an inscription of sheer existence” (Casella Reference Casella2014: 108). In this case, the archaeological record adds to the dry accounts of the daily toil of the whalers found in the historical sources.

Figure 7. Map showing the route of the Delta in 1849 and 1850 in the Eastern Indian Ocean, and the location of whale grounds based on modern data (figure by Lucia Clayton).

Discussion

The discovery of these North American whalers’ inscriptions has substantial implications for North West Australian history. Although the presence of American vessels in the Eastern Indian Ocean has been long known, we understand surprisingly little about these historical activities—particularly in the Dampier Archipelago. These new inscriptions raise questions about maritime frontiers in North West Australia. What can these sites (and the contemporaneous archival record) tell us about the presence of American whalers in this area? What are the implications for our understanding of early relations with the Yaburara people, especially given the traumatic colonial history that followed the establishment of pearling and pastoralism?

The American whaling maritime frontier was a global phenomenon lasting for several centuries. At its peak in the mid nineteenth century, around 900 vessels were at sea on multi-year voyages, crewed by approximately 22 000 whalers (Schürmann Reference Schürmann2012). Visits by whalers to remote African, Pacific and Australasian territories led to early social and economic contact between crews and Indigenous societies. Their exploratory, commercially driven visits were a formative part of early colonisation processes and cultural expansion by Northern Hemisphere maritime powers—resulting in significant and lasting impacts on Indigenous populations (Gibson & Whitehead Reference Gibson and Whitehead1993; Schürmann Reference Schürmann2012; Anderson Reference Anderson2016). Despite being driven largely by commercial motives, “encounters, exchanges, and communication between whalemen and coastal dwellers” (Schürmann Reference Schürmann2012: 28) were also essential attributes of these voyages.

The presence of American whalers, and the archaeological evidence for their crews’ personal marking of the landscape (Rockman & Steele Reference Rockman and Steele2003), allows us to review the current understanding of contact and colonisation of North West Australia. Colonisation is commonly thought to have begun in 1863, with the more permanent arrival of white settlers (Paterson Reference Paterson2006). The Flying Foam Massacre, which followed shortly thereafter in 1868, illustrates the colonial violence and threats to traditional Aboriginal society that loomed on the horizon. The American whalers, however, preceded this more permanent European expansion into the area, recording a brief moment when Indigenous people and visiting whalers shared territory without obvious major conflict. If whalers are recognised as part of the contact phases of the colonisation process, the arrival of white ‘outsiders’ in North West Australia should perhaps be reconsidered to date to the early, rather than mid, nineteenth century. This earlier economic ‘colonisation’ was maritime, coastal and seasonal—timed for the Southern Hemisphere winter, when migratory humpback whales were present.

As non-permanent visitors with little interest in land-based settlement, whalers posed less of a threat to the Yaburara people than did later colonists. Unlike later white settlement, there was no direct competition for land, and no terrestrial colonial presence. As with all forms of contact, however, there may have been the potential for the exchange of items, knowledge and disease. The whalers would have seen the fires of the Yaburara people on the islands and coasts, and, in making their inscriptions on these islands, they would have been aware of the existing marks made by the local inhabitants. Indeed, disease may have had profound implications for encounters between whalers and the Yaburara people. On a subsequent voyage, in 1854, the Delta visited the island of Pohnpei, in Micronesia, to bury several crewmen who had died of smallpox. Local indigenous people contracted smallpox, which ravaged the island's population. An estimated half of the Pohnpeiians—including many high chiefs—died over the following months (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1988: 109–12). There is no similar record for whaling visits as disease vectors in Australia's North West, although this earlier period of contact has been little studied.

A range of maritime inscriptions has been found previously on the coasts around Australia's whaling grounds. These include graffiti, cairns containing bottles and messages, carved wooden posts and carvings on trees (Green Reference Green2007: 1–104; Anderson Reference Anderson2008; Frederick & Clarke Reference Frederick and Clarke2014; Gibbs & Duncan Reference Gibbs, Duncan, von Arbin, Nymoen, Stylegar, Sylvester and Gutehall2015). These inscriptions show a diverse range of memorialising behaviour to record and commemorate voyages and landfalls—whether they were brief landings or lengthier stays—and a way of communicating the (sometimes last known) location of a vessel and its crew. Maritime inscriptions on rock, however, are rare. Of 23 recorded Australian historical maritime inscriptions related to early exploration made between 1616 and the twentieth century, only six are rock engravings (Anderson Reference Anderson2008: 60).

Maritime inscriptions “symbolised efforts to establish or contest landscapes [and] provided an important tangible cultural symbol in an often hostile natural world [by] stamping cultural markers on natural landscapes” (Gibbs & Duncan Reference Gibbs, Duncan, von Arbin, Nymoen, Stylegar, Sylvester and Gutehall2015: 224–25). The placement of the Delta and Connecticut inscriptions in close proximity to—or even superimposing—Indigenous engravings graphically and symbolically demonstrates a “trespass and act of usurpation” (Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke and Frederick2016). The effect of this, prior to British colonisation of the North West, was a colonial reordering of space. It can be assumed that the Yaburara were well aware of the Connecticut and Delta, and other whalers, although the nature and extent of any cross-cultural interaction remain unknown. That the Delta logbook never refers to encounters with Indigenous Australians may indicate that they avoided the whalers, or more likely, that these encounters were deemed to be of insufficient importance to be recorded. The whalers probably observed Yaburara people moving between islands on their log boats—a practice first recorded by Phillip Parker King in 1812. Perhaps significantly, King believed that the Yaburara were already familiar with European metal objects, as they were indifferent to his gifts; this hints at even earlier and undocumented visits by whalers (Cunningham Reference Cunningham1816–1819; King Reference King1818).

The inscriptions left by the whalers provide new insight into early, previously unrecorded cross-cultural encounters. The placement of the Delta and Connecticut inscriptions on already richly decorated rock surfaces suggests a deliberate process of selection, which attempted to engage with the Aboriginal markings and, indirectly, the Yaburara themselves. Superimpositions in rock art (Harris & Gunn Reference Harris, Gunn, David and McNiven2017) may be intentional or non-intentional. Non-intentional superimpositions occur when the artist has an indifference towards previous depictions, or where there is a lack of space on the rock surface. Intentional superimpositions occur when an artist chooses to eliminate previous marks by purposively covering, replacing or obliterating them (Kaiser & Keyser Reference Kaiser and Keyser2008; Re Reference Re, Bednarik, Fiore, Basile, Kumar and Huisheng2016). The Delta and Connecticut inscriptions appear not to eradicate the older markings, but rather to begin a conversation on stone.

The placement of both Murujuga whaling inscriptions over earlier Aboriginal petroglyphs probably signifies the importance of place in the act of mark-making. Generations of artists sat in the same locations and surveyed the landscape, and it would appear that their mark-making was not necessarily stimulated by a need to signal information to any particular audience (McDonald Reference McDonald1999): neither can be seen from the water on approach. In both cases, reaching the locations of these historical inscriptions requires physical effort, and viewing the marks requires the audience to stand directly above them. These marks were not intended to signal corporate identity, or to be emblematic in nature (Wiessner Reference Wiessner1984; Sackett Reference Sackett, Conkey and Hastorf1990; McDonald Reference McDonald1999; Bradley Reference Bradley2009). Nor were they an institutionalised political statement made to reinforce (or contradict) an existing power structure (Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke and Frederick2016). The long-term use of these places by Aboriginal people to signal their presence during their seasonal economic round (i.e. while quarrying tool stone; McDonald Reference McDonald1999) resulted in petroglyphs being engraved on most available surfaces. Thus, the opportunity for the whalers to find a ‘blank canvas’, in either of these locations, was rare. By recording their presence at these specific historical moments, the whalers were continuing the long tradition of the preceding hunter-gatherer-fisher people in surveying and interacting with their maritime environment. While maritime historical graffiti are sometimes characterised as commemorative, performative and reiterative, the whalers’ inscriptions do not signal at a distance, but, instead, make an insistent point about the creators’ history, identity and identification with the place (Bashford et al. Reference Bashford, Hobbins, Clarke and Frederick2016; Clarke & Frederick Reference Clarke and Frederick2016). Part of the significance of the whalers’ markings is that they provide insight into motivations for inscribing the landscape generally.

Both the Delta and Connecticut inscriptions appear to have been unofficial personal markers made by one or more crewmembers. Thus, they provide some personal insight into the lives and behaviours of these whalers. The Connecticut’s 19 year-old African-American seaman Jacob Anderson was obviously literate; his careful script, skilfully engraved over an existing grid, commemorates an anniversary in the Connecticut’s voyage to the Southern Hemisphere. J. Leek's Delta inscription, along with several additional marks made at this same location—presumably made on the same day—provides significant insight both into early North West Australian maritime history and the voyages of the Delta—otherwise thinly documented in the historical records.

These whalers’ inscriptions provide important new evidence in North West Australia for the North American whaling on the Indian Ocean frontier. They represent the only tangible evidence of this earliest phase of white colonisation of the North West so far discovered. As highlighted by their creators, these marks confirm the character of this early colonisation phase as maritime, seasonal, coastal and liminal. For a variety of reasons—but probably mostly as a result of the diminishing whale stocks—North American whalers ceased to visit the New Holland Ground, before more permanent white colonisation had its terrible consequences for the Yaburara and other Aboriginal people of North West Australia. These two whaling inscriptions provide the only known archaeological insights into colonial-Indigenous encounters prior to the better-documented and more violent history that began later in the nineteenth century. So ends this day.

Acknowledgements

This research forms part of the ‘Murujuga: Dynamics of the Dreaming’ ARC Linkage Project (LP140100393). Fieldwork was completed under the guidance of the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation Circle of Elders and was facilitated by the Murujuga Land and Sea Unit. Victoria Anderson and Sarah de Koning found the Connecticut inscription. Photographic recording and microscopic analysis of the Connecticut panel was completed by McDonald and Mulvaney. McDonald and Paterson recorded the Delta panel. Both inscriptions were traced digitally by Mulvaney using Adobe Photoshop. Data were audited by de Koning and McDonald; rock art analysis and D-Stretch were performed by McDonald. All authors contributed to the text. We are grateful to Lance Dennis for reporting the Delta engraving to the Western Australian Museum. Kayla Correll of the New London County Historical Society provided assistance with research into North American historical sources.