Introduction

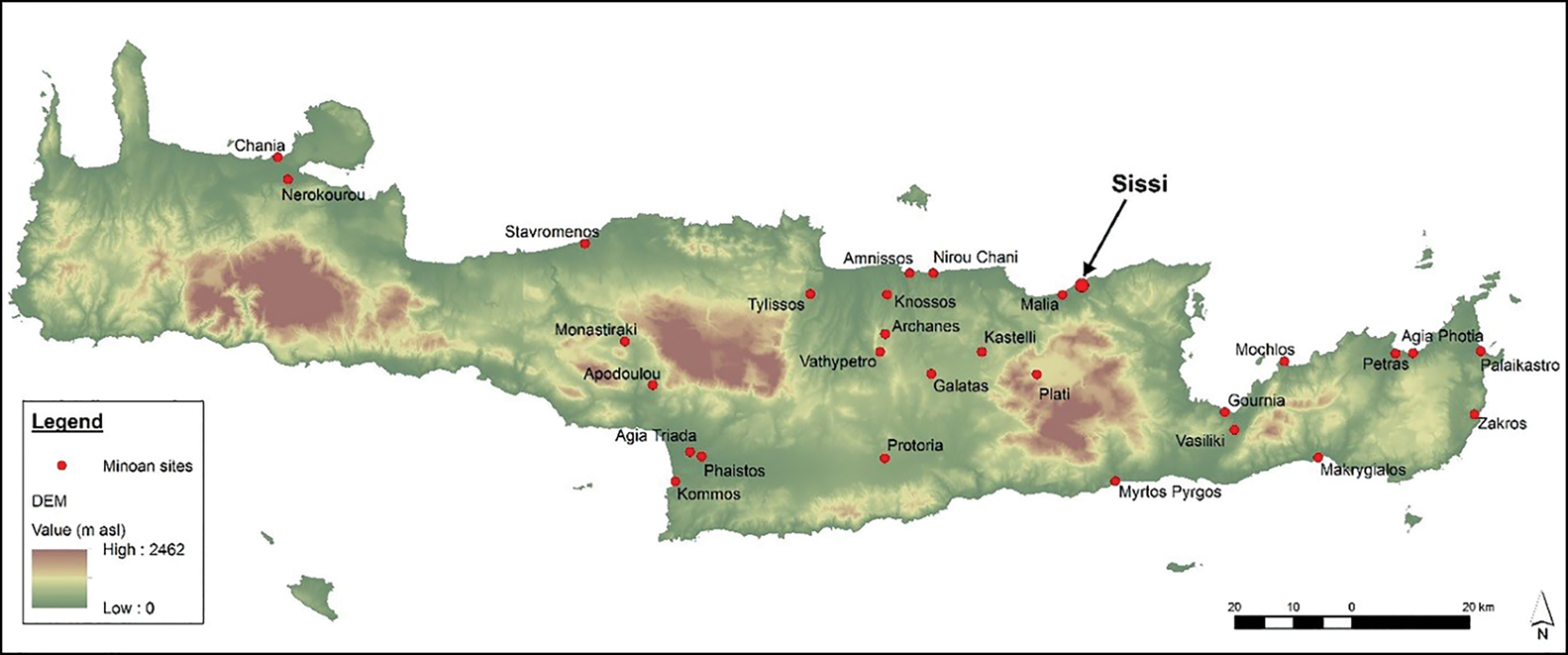

During the Bronze Age (c. 3000–1200 BC), the island of Crete was home to a flourishing, literate culture—the Minoan civilisation—that was characterised by the presence of large-scale, elaborately decorated complexes organised around a central court, commonly referred to as ‘palaces’ (Figure 1). The first of these palaces were constructed at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1950 BC), known as the Protopalatial period. Following their destruction, by human or natural forces, several palaces were rebuilt in the Neopalatial period (seventeenth century BC), but were again destroyed in the middle of the fifteenth century BC, never to be rebuilt (Graham 1962; McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010). While the palace of Knossos was certainly the largest, similar complexes have been excavated in several regions of the island: at Phaistos, Malia, Zakros, Galatas, Gournia and Petras; further complexes are suspected beneath modern towns, such as at Chania and Archanes (McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010: 89). Scholars continue to debate the nature of the occupation of these palaces, their interrelations and the political role they played at various points in Minoan history (e.g. Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2016; Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw, Relaki and Papadatos2018). The recent discovery of a monumental complex at Sissi not only provides new evidence for the function of the central courts of such palaces, highlighting ritualised communal gatherings, but also stresses the importance of the integration of earlier ruins within such buildings. These would have helped to increase the social power of the structure, linking it with an ancestral presence at the site.

Figure 1. Map of Crete showing important Bronze Age sites (courtesy of S. Déderix).

Sissi

The Kephali hill at Sissi is located on the north coast of Crete, approximately 4km east of the major contemporaneous settlement and palace complex of Malia. Since 2007, the site has been the focus of excavations by the Belgian School at Athens (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2009, Reference Driessen2011, Reference Driessen2013, Reference Driessen2018). Situated opposite the Selinari Gorge—the only overland communication route between central and eastern Crete—and with beaches on either side, the hill had obvious strategic advantages. This may explain why it was occupied from 2500–1200 BC, mirroring the occupation of nearby Malia. But while Malia exponentially grew from a 4ha village during the Early Bronze Age to a 50ha town in the Middle Bronze Age (Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw, Relaki and Papadatos2018: 232), when a palace was also constructed there (c. 1950 BC), the Kephali occupation remained small in scale (3ha) and confined to its low coastal hill. The proximity of Sissi to Malia makes for a useful case study through which to explore the relationships between first- and second-order centres. We can also compare patterns of production and consumption within a shared intra-regional material culture to examine changing forms of interdependence.

While most of the structures thus far excavated at Sissi (Figure 2) seem to have had a residential function, the size, organisation, court and ashlar façades of the complex located on the south-eastern summit of the hill suggest that this particular area fulfilled a more public role (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2013: 145). Originally identified through geophysical survey (Sarris et al. Reference Sarris, Manataki, Déderix, Driessen, Jennings, Gaffney, Sparrow and Gaffney2017; Driessen & Sarris Reference Driessen and Sarris2020) (Figure 3), the complex was excavated over five excavation campaigns, which have confirmed both the size and the shape of the central court of the complex. Although further investigations are required, notably concerning the chronology of some of the walls, most of the court building has now been revealed (Figures 4–5). Present evidence suggests that the Sissi complex was built early in the Middle Minoan IIIB, c. 1650 BC, during the Neopalatial period. Traces of volcanic ash found in some of the abandonment layers indicate abandonment of the court building immediately before or contemporaneous with the Santorini eruption in the Late Minoan IA period, c. 1550/1530 BC (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2018: 38–42). This relatively short chronological range echoes that of some of the other Neopalatial palaces on Crete, such as at Galatas and perhaps at Petras (McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010: 82–83; Rethemiotakis & Christakis Reference Rethemiotakis, Christakis, Macdonald and Knappett2013).

Figure 2. Aerial view of the Sissi excavations (figure by N. Kress; © Belgian School at Athens).

Figure 3. Geophysical results superimposed on the 2011 architectural plan (figure by A. Sarris; © Belgian School at Athens).

The court building at Sissi

At approximately 2000m2, and with a central court of around 15.50 × 33m (approximately 460m2), the extent of the Sissi complex is surprising, considering the small size of the associated settlement and the presence at nearby Malia of a palace with a 22 × 51m court (similar in size to those at Knossos and Phaistos; McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010: 84). On the other hand, the first-order centre at Petras near Siteia has a much smaller central court (78m2). Even the court at Zakros is smaller (368m2) than the one at Sissi, while that at Galatas is somewhat larger (580m2) (Vansteenhuyse Reference Vansteenhuyse, Driessen, Schoep and Laffineur2002: 247). That the court at Sissi was the principal feature of the architectural complex is indicated by its direct accessibility from all sides via finely paved passages, as is the case at the other major Minoan palaces (Palyvou Reference Palyvou, Driessen, Schoep and Laffineur2002). The court itself was carefully laid out, and featured a floor of bright lime plaster set with small pebbles. While the size and character of the court are surprising, so is the irregularity of the overall plan of the Sissi complex. The four wings are of relatively small dimensions, and it is clear that they have been conceived from the inside-out, with the ashlar court-facing façades being of particular importance as backdrops for whatever activities happened in the court (Figures 4 & 5). Each wing seems to have been constructed as a separate unit, with differing orientations and using different construction techniques and masonry types. Calcareous sandstone ashlar, for example, was used for some of the façades facing the court, while rubble masonry was used elsewhere. Much of the complex, including some of the ashlar façades, was decorated with brightly painted plaster.

Figure 4. Aerial view of the court complex at Sissi at the end of the 2019 campaign (figure by N. Kress; © Belgian School at Athens).

Figure 5. Preliminary outline plan of the court complex at Sissi (figure by E. Zografou; © Belgian School at Athens).

The shape of the central court is awkward and demands explanation, as it is not rectangular, uniformly oriented or of regular proportions. While it seems clear that the concepts of rectangularity, orientation and proportion (i.e. the 2:1 length:width ratio that dictated the size of courts)—as evidenced in the major Minoan palaces—were also present during the layout of the Sissi court building, its provincial character or relatively early date of construction could be responsible for its unusual features (Palyvou Reference Palyvou, Driessen, Schoep and Laffineur2002; Shaw Reference Shaw and Krzyszkowska2010: 305). There may, however, be other reasons that reach beyond simple emulation processes. In the north-west corner of the complex in particular there are substantial Early Bronze Age architectural remains and ceramic deposits (see Figure 5). The terrace wall that retains these deposits is of monumental construction and comprises large boulders (Figure 6). This early wall may have been located next to an open yard—a predecessor of the central court. If this was the case, Sissi may have displayed social complexity at an early stage (c. 2500 BC), as evidenced at several other Minoan centres, such as Knossos, Malia and Phaistos (Driessen Reference Driessen, Bretschneider, Driessen and van Lerberghe2007; Shaw Reference Shaw and Krzyszkowska2010: 306–307). The incorporation of Early Bronze Age remains into the later complex may have been a conscious decision and an attempt to link the new complex to ancestral practices.

Figure 6. North-west corner of the court at Sissi, showing: A) ashlar walls; B) the Early Bronze Age terrace wall behind; C) the elevated platform and (D) room in the corner; E) the northern entrance passage; F) the bench with hollows along the north side of the court (figure by N. Kress; © Belgian School at Athens).

These Early Bronze Age structures may have influenced the first stage of the later construction, as the north part of the east wing seems to follow the same orientation (north-west to south-east). While the unit added at a later stage on the south side of the east wing also seems to follow the same orientation, none of the other units does so. The west wing has a more north-east to south-west orientation, but why this is the case remains uncertain. Small changes in orientation between successive architectural phases have also been noted in other palaces, as at Malia, Phaistos and Knossos (Shaw Reference Shaw, Caratelli and Rizza1973, Reference Shaw and Krzyszkowska2010: 305). Another potential reason for the unusual shape of the Sissi complex is that it may have been adapted to an existing street system. The walls bordering the finely paved access passages into the central court (Figures 4–6) were built on top of paving slabs, suggesting that the road surfaces are older and perhaps originally formed part of a route encircling the top of the hill, where identically paved roads still exist (see Figure 2). Yet another reason may be that the entire south part of the complex was a later addition, although still constructed within the main period of use.

Not only are the orientations of the southern units different from their northern counterparts, but their masonry also differs. The southern units use rough boulders, while the northern units comprise ashlar. A final reason for the court's unusual shape may be local topographical conditions and the availability of space (Figure 4): the complex was squeezed to fit into a large depression in the bedrock. While the base of this depression was levelled in the court area, substantial outcrops were incorporated in the architecture of the surrounding wings. The specific location of the Sissi complex may, conceivably, also have been influenced by other conditions, such as, for example, astronomical observations.

These observations clearly suggest that the construction of the court and surrounding complex was a gradual undertaking. In its original phase (Middle Minoan IIIB, c. 1650 BC), the complex must have had a U-shape, with the court probably open to the south. U-shaped central courts have also been suggested for the early phases of other Minoan palaces (Moody Reference Moody, Hägg and Marinatos1987). But even when the Sissi court was gradually enlarged, an open view to the south was retained, as all additional spaces to the south of the massive court-retaining wall were at a lower level. Hence, a view towards the Selena Mountains, which form a natural backdrop to the site, seems to have been an essential consideration. This topographical and spiritual linkage with the natural environment and particular landmarks has been noted at Knossos (with the peak sanctuary on Mount Iuktas) and Phaistos (with the twin peaks of Mount Ida) (Shaw Reference Shaw, Caratelli and Rizza1973). The later enlargement of the court from around 250 to 460m2, within the same Middle Minoan IIIB phase, nearly doubled the potential number of participants that the court could accommodate, from approximately 55 to 100 people (milling) and from around 165 to 300 (standing closely) (cf. Gesell Reference Gesell, Hägg and Marinatos1987: 126).

The Sissi complex was abandoned in the Late Minoan IA period (c. 1550/1530 BC) and, apart from a few ceramic sherds, very little of importance was left within its rooms. The abandonment may have been accompanied by attempts to block access to the complex, or at least to its court, as both the south-west and north-east access passages were found to have been blocked (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2011: 169) (Figure 5). During the Early Iron Age (1200–800 BC), the court itself—although sedimented over—may still have formed an open area that was occasionally used for minor ritual depositions (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2018: 182 & 187), as observed within other Minoan ruins (Prent Reference Prent, Van Dyke and Alcock2003).

The function of the Sissi court building

Why was a complex with a central court built so close to Malia where, within the palace, a much larger court was available? Answering this question would have wider implications, as it would help us to understand the purpose and function of Minoan palaces. Did the complex at Sissi pre-date the palace at Malia? Although studies on the chronology of the Neopalatial Palace at Malia are ongoing (Devolder Reference Devolder2016), there is some evidence of a monumental construction of the Middle Minoan IIIB phase (c. 1650 BC), following the destruction of the earlier Middle Bronze Age palace, but preceding the Late Bronze Age complex (c. 1600 BC) (Poursat Reference Poursat1988: 75). This ‘intermediate building’ would be contemporaneous with the court building at Sissi. The Sissi complex would also overlap considerably in time with the subsequent Late Minoan IA Palace at Malia.

A second hypothesis, which cannot currently be fully substantiated, is that the Sissi complex was established as a Knossian outpost—a territorial marker potentially intended to impress nearby Malia. A similar scenario has been proposed for the Zakros and Galatas palaces (Wiener Reference Wiener, Betancourt, Nelson and Williams2007). Growing Knossian influences on ceramic-manufacturing and architectural techniques can be identified at Sissi during the Neopalatial period (Middle Minoan IIIA–Late Minoan IA) (Devolder Reference Devolder2018; Mathioudaki Reference Mathioudaki and Driessenin press), and the favourable topographic location of the settlement would have had obvious strategic advantages in the controlling of local land and maritime communications (a position exploited for similar reasons during the Second World War, when Axis forces occupied the hill) (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2011: 24–25). Moreover, administrative boundaries dating from the late antique period (AD 400) onwards (Bennet Reference Bennet1990: 200–205) have been located at Sissi. Hence, the notion of a borderland function may date back even earlier.

A third hypothesis that could justify the construction of a court building at Sissi may be associated with its local social function. Halstead (Reference Halstead, Sheridan and Bailey1981: 201) noted that Minoan palaces might be considered as a combination of Buckingham Palace, Whitehall, Westminster Abbey and Wembley Stadium, drawing attention to their numerous functions. These clearly included production, storage, consumption, administration, ritual, religion and political residence, all of which can be identified in the four major palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Zakros, and, to a lesser extent, at Gournia, Petras and Galatas (McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010: 83–89). This is not the case at Sissi, however. Here, there is no evidence for administration, but as there was no fire-related destruction, one would not expect expository clay documents to be preserved. Nor is there any evidence for the production of pottery, stone vases, jewellery, or agricultural produce or processing. What is perhaps most surprising, however, is that there is no evidence for storage facilities. Other than an occasional sherd, not a single pithos has been found in the Sissi complex, and it seems unlikely that these cumbersome jars were all removed during the abandonment process. Moreover, the Sissi complex lacks the ubiquitous parallel storage spaces that typify so many Minoan palaces. This leaves us with consumption, ritual, religion and political residence as potential functions, and at least the first three of these are well represented in the Sissi complex. The size and architectural quality of the court and the presence of finely paved, direct, access routes leading into the court stress the permeability of the complex, and suggest that quick access into the central court for larger groups was a major concern. Within or bordering the court are several installations that can only be explained as serving specific ritual purposes, the precise nature of which remains uncertain. Next to an entrance from the court into the east wing, for example, there is a large, in situ limestone block featuring approximately 30 shallow depressions of varying diameters (Figure 7). Similar stones are known as kernoi and are quite common at Minoan sites; the circular marble kernos at the nearby Malia palace is the most striking example (Cucuzza Reference Cucuzza2010).

Figure 7. Sissi kernos (figure by J. Driessen; © Belgian School at Athens).

While various interpretations exist for such kernoi (Letesson Reference Letesson2014), they were probably intended for the ritual deposition of small substances of some kind. Furthermore, the north wall of the central court at Sissi is flanked by a low bench made of large slabs that also exhibit shallow depressions (Figure 6F). These too seem to have served for the deposition of specific, small items. Close to the centre of the court is a circular, burnt clay structure (a possible hearth) with a diameter of approximately 1m and surviving to a height of 0.30m (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2018: 285). It was found to be full of ash, charcoal and stones. Its location is comparable to a square structure in the centre of Malia's palace court, the function of which is unknown. Less than 2m east of the circular structure at Sissi is a thin layer of dark grey ash on the surface of the court, within which lay several dozen miniature goblets (Figure 8), some pushed into the court's surface. The Sissi goblets formed part of one or more composite vessels, perhaps originally deposited inside the circular, burnt clay structure. Similar contemporaneous goblets forming part of composite vessels were found at the peak sanctuary of Vrysinas, within a ritual context (Tzachili Reference Tzachili2016: 178–80 & figs 4 & 57).

Figure 8. Fragments of miniature goblets from Sissi; the scale is in centimetres (figure by C. Papanikolopoulos; © Belgian School at Athens).

On the south-west border of the court are two more installations that potentially had ritual functions. The first consists of two upright standing stones next to a small stone platform, immediately to the north of the access to the court from the western passage. These stones are worked, but their tops are damaged (Figure 9). I have previously suggested that they are the remains of large Horns of Consecration, the Minoan religious symbol par excellence, which could have played a role in astronomical observations (Shaw Reference Shaw, Caratelli and Rizza1973; Driessen Reference Driessen2017).

Figure 9. South-west side of court at Sissi. From left to right: A) stone platform; B) western entrance passage; C) potential Horns of Consecration (figure by J. Driessen; © Belgian School at Athens).

The second installation is to the immediate south of these putative horns, and comprises an area paved with large slabs (Figure 9), next to which a fine stone vase was found. The function of the paving and vase are no longer clear, but such paved areas have often been assigned a ritual interpretation, such as receiving blood sacrifices and libations, as at Gournia (Soles Reference Soles1991: 52).

In the north-west corner of the court is a small, elaborately paved and plastered room, accessible via a stepped entrance and constructed against the Early Bronze Age façade mentioned earlier (Figure 6) (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2018: 219–25). The attention given to its construction and the fact that it is located precisely where the Throne Room at Knossos and the Loggia at Malia are situated—both spaces for which a ceremonial and ritual function has been claimed (Graham Reference Graham1962; McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010)—make it tempting to attribute a similar role to the room at Sissi. Next to the wide-stepped entrance to this room is an elevated platform, also built against the Early Bronze Age façade, but somewhat later than the room itself (Figure 6). It was accessible via a now-collapsed stone staircase. Against the north wall of the central court of the Palace of Phaistos is also a stepped platform that, due to its resemblance to a depiction on Bronze Age seal-stone of an athlete jumping on a bull, has been interpreted as having a connection with bull-leaping (Graham Reference Graham1962: figs 52–54). This interpretation, however, is perhaps unlikely, considering that the court at Sissi was finely plastered.

Finally, mention should be made of a few notable ceramic containers, such as a bull rhyton, found close to the north entrance of the court, and a vase fragment decorated with a relief bucranium found on the court surface. The combined presence of these features supports the argument that the court at Sissi was used for rites and ceremonial activities. The variety of attested rituals is surprising: some may have involved the deposition of perishable items, while others may have been associated with fire or blood sacrifices, libations or simply connected to astronomical observations and various performances. The ashlar façades around the court provided a monumental backdrop for all of these activities. There is also strong evidence that some of the ceremonies may have involved, or were accompanied by, the large-scale consumption of beverages.

That the Minoan palace courts were used for ritual, communal gatherings is certainly not a new idea, but apart from spatial considerations and some iconographic evidence, the indications are limited (Moody Reference Moody, Hägg and Marinatos1987; Driessen Reference Driessen, Relaki and Papadatos2018). To a large extent, the early date and/or unpublished state of the excavations of some palaces is to blame. Studies on recently found deposits from the palaces at Galatas and Gournia (Girella Reference Girella2007; Rethemiotakis & Christakis Reference Rethemiotakis, Christakis, Macdonald and Knappett2013; Watrous et al. Reference Watrous2015), as well as evidence for such communal gatherings from the Early Bronze Age onwards at Knossos and Phaistos (Day & Wilson Reference Day, Wilson and Hamilakis2002; Todaro Reference Todaro2013), can now be supplemented with the evidence from Sissi. An assemblage of 148 simple and eight elaborate cups, carefully placed within a plastered bench in the east wing, may have accompanied building activities around 1600 BC (Caloi Reference Caloi2018). Other ceremonies may have been held on a cyclical basis, as suggested by a massive deposit comprising more than 2000 cups of various shapes, found in the south part of the west wing (Mathioudaki in press). If our interpretation of the stratigraphy of this latter deposit is correct, it suggests repeated gatherings of large groups between 1600 and 1550 BC. The structured deposition or curation that is illustrated by both deposits underlines the ritual nature of these gatherings. Moreover, the absence of storage spaces and containers within the complex implies that local communities actively participated and brought consumables with them. Such ritualised communal feasts and gatherings must have served to integrate the different constituents of society—the various households living in the associated settlement (Girella Reference Girella2007). As the court, after its extension, seems excessively large for the local community residing on the hill, we can hypothesise that people from farmsteads in the surrounding countryside also participated.

Conclusions

The excavations of the Minoan court building at Sissi suggest that, despite a general resemblance to structures commonly known as ‘palaces’, the complex did not serve all of the functions associated with such palaces. This may imply that, despite having a more or less identical plan, these public structures had varied functions. Moreover, if a minor settlement such as Sissi was deemed important enough to include a court building, one may assume that many other settlements must have housed a similar structure. The question of whether there was correlation with community size requires further research. The Sissi case, however, warns us against oversimplification. Within Minoan studies, the presence of a palace was never judged to be a sufficient argument to assume political autonomy, and the Sissi complex may corroborate this (Warren Reference Warren, Cadogan, Hatzaki and Vasilakis2004; Knappett et al. Reference Knappett, Rivers and Evans2011). The proximity of Malia and its palace makes it a priori unlikely that the Sissi settlement enjoyed much independence, and whatever political system one advocates—hierarchical/heterarchical, centralised/decentralised or a mixture of these—the populations of the two sites must have, to some extent, been integrated, had comparative access to leadership positions and involvement in group decisions.

Finally, if we consider that substantial Early Bronze Age ruins were left for several centuries before being incorporated within a much later structure, one may ask to what extent this reuse informs on processes of continuity of occupation or other means of cultural transmission. The least this demonstrates is that, from a place of memory, there was a development of these ruins into a place of social power, and that the incorporation of ancestral ruins added considerable authority to the structure. The evidence at Knossos and Phaistos suggests that local communal gatherings may already have been essential for social integration in the Early Bronze Age, and the evidence at Sissi fits this scenario (Day & Wilson Reference Day, Wilson and Hamilakis2002; Todaro Reference Todaro2013). There is no evidence, however, for such gatherings taking place at Sissi during the Middle Bronze Age (Middle Minoan I–II), the period during which nearby Malia grew exponentially in size, becoming highly urbanised, with public, monumental structures built alongside the palace (Poursat Reference Poursat1988; Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw, Letesson and Knappett2017). Does this imply that, during this phase, Malia thwarted local initiatives? Did the same happen after Late Minoan IA, when the Sissi court building was abandoned while the settlement persisted? If Knossos was involved in the initial construction of the Neopalatial complex at Sissi, perhaps the court building was abandoned because it no longer served the needs of the central authority now controlling the region, as suggested by the ceramic and architectural evidence mentioned above? Or is there another explanation?

It was previously noted that tephra from the Santorini eruption was found in the abandonment layers of the Sissi court building. While we cannot claim that this volcanic material caused sufficient damage to explain the abandonment of the complex, the possibility that eruption-related impacts affected mass gatherings in courts—ceremonies in particular and rituals in general—cannot be precluded. Major religious changes in this post-eruption phase included the downgrading of a female divinity and the abandonment of nature shrines, such as mountain-top sanctuaries and caves (Driessen Reference Driessen2019). If, as we have suggested, the gatherings in the Sissi court were intimately connected to rituals, sacrifices and religious beliefs, changes in the latter would have eliminated the raison d’être and legitimacy of the court and, by extension, the structures around it. Attributing a primarily ceremonial and religious function to the Sissi court building and thus, to some degree, taking the evidence at face value, has implications for our interpretation of the role of the other Minoan palaces, as the incorporation (or not) of additional functions (e.g. production, storage, administration) clearly introduces some type of categorisation and differentiation in the continuum of architectural representation. It also brings us one step closer to a more nuanced understanding of Minoan political geography.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Sinclair Hood. The Sissi Archaeological Project (www.sarpedon.be) took place under the auspices of the Belgian School at Athens, and was conducted in the field by an international team under the direction of the UCLouvain. The author expresses his warmest thanks to the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and the Archaeological Service of east Crete for granting the permission to do work at Sissi, but also to the local communities of Sissi and Vrachasi and the successive investigative teams. I am grateful to the Sissi court building supervisors, T. Claeys, S. Déderix, M. Devolder, E. Hayter, S. Jusseret, Q. Letesson, T. Mumelter and O. Mouthuy, and to the project's ceramic specialists, C. Langohr, I. Mathioudaki and I. Caloi, for their help and collaboration, N. Kress for general assistance and E. Zografou for the plans. The article also benefited from remarks by the anonymous reviewers.

Funding statement

Work at Sissi would have been impossible without the various funding bodies, including the Belgian School at Athens, the UCLouvain, the Institute for Aegean Prehistory, the Loeb Classical Library, the FNRS, the Rust Family Foundation, as well as a series of other sponsors, private and institutional. The article forms part of the Talos Project (ARC 20/25-106).