Introduction

The ways in which traditions of pottery production from around the world vary may often be interpreted as a reflection of the cultural processes in the society where potters interact. Some may be more obvious than others, but even more nuanced variations may represent significant changes involving technical gestures and specialist knowledge. Here, vessel thickness is used to evaluate changing social and environmental contexts of production in Antofagasta de la Sierra (Catamarca, Argentina) during the transition from the Formative (c. 5000/3000–1000 BP) to the Late period (c. 1450–700 BP).

Antofagasta de la Sierra

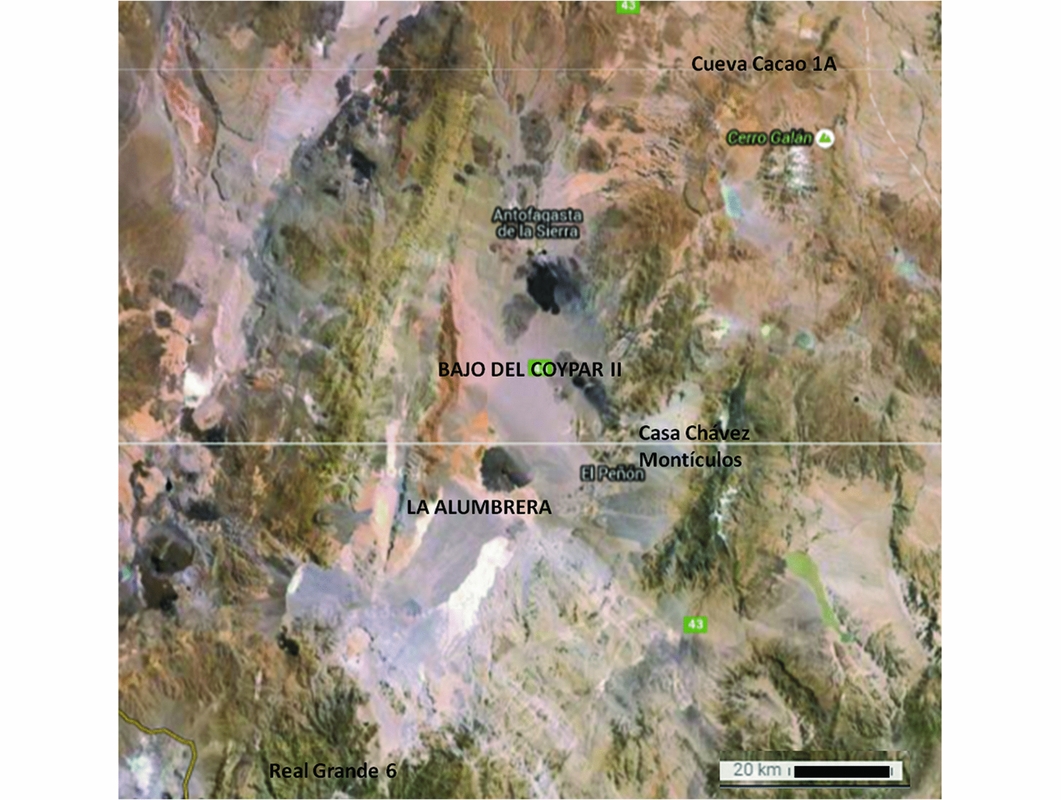

Antofagasta de la Sierra is a high desert in Puna de Atacama, characterised by intense solar radiation, variable daily temperature, strong seasonality, minimal summer precipitation, low atmospheric pressure and the irregular distribution of biotic resources due to differing localised weather, topography and geology (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Tchilinguirian and Aguirre2002). The unusual relief of the landscape (the basin at 3400–3550m asl with intermediate sectors and high ridges peaking at 3900m asl) and the irregularity of rainfall have traditionally constrained settlement during the Formative to areas with higher densities of biotic resources such as the Antofagasta lake basin (Figure 1). Vegetation comprises an abundance of bushes, halophilous and herbaceous steppe and marshes, while camelids, rodents, felids, lagomorphs and birds account for most of the fauna (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Tchilinguirian and Grana2004).

Figure 1. Overhead satellite imagery of the area of Antofagasta de la Sierra, showing the sites mentioned. Formative sites: Casa Chávez Montículos; Real Grande 6; Cueva Cacao 1A. Late-period sites: Bajo del Coypar II; La Alumbrera.

Following an earlier occupation of the area by hunter-gatherer groups, cultivation and herding economies have been established since c. 5000/3000 BP. Early permanent settlements were marked by a reduced residential mobility and a tendency towards the reoccupation of previously inhabited areas. Significant social changes implying territoriality, long-distance exchange and an increase in population density have also been inferred (Hocsman Reference Hocsman2002).

The Formative period

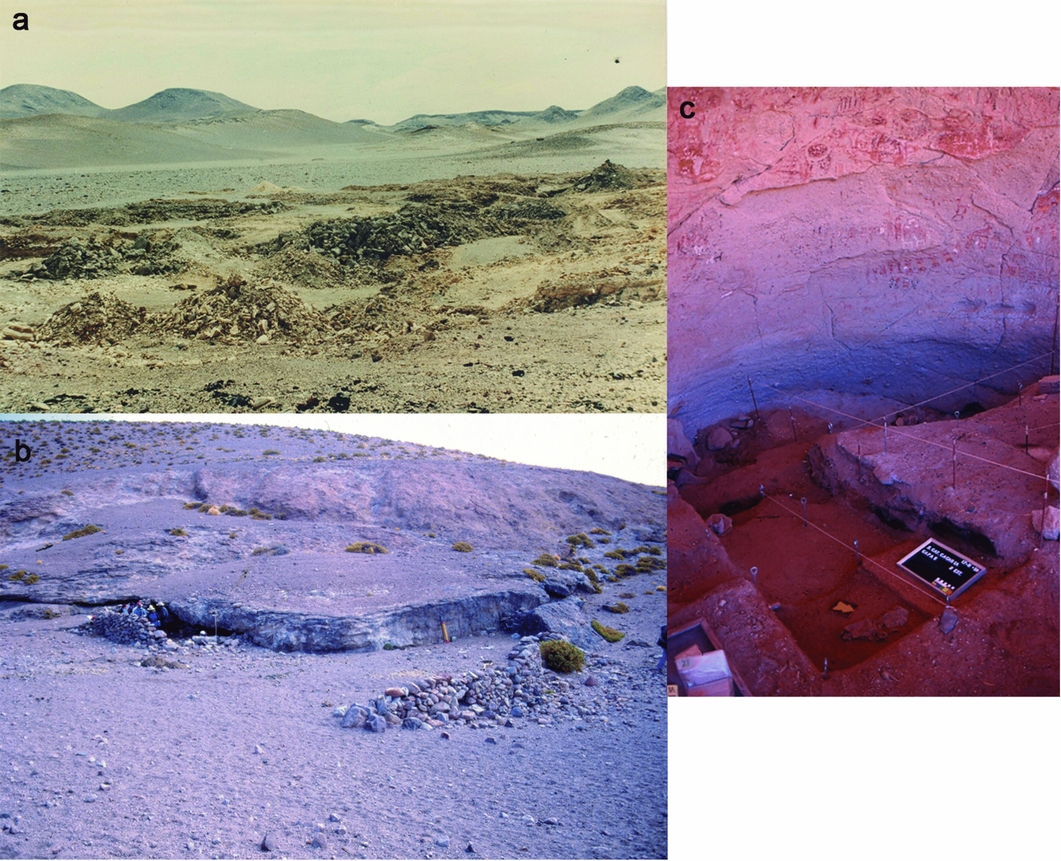

The Formative (Figure 2) was characterised by a broad spectrum economy (herding, hunting, agriculture and foraging) dominated by camelid husbandry (Aschero Reference Aschero and Tarragó2000; Hocsman Reference Hocsman2002; Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Tchilinguirian and Aguirre2002), and complemented by wild faunal resources such as vicugna from higher geographic elevations to compensate for food shortages. A reduction in 18O and 13C isotopic values indicated more humid conditions until c. 1600 BP (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Tchilinguirian and Aguirre2002), creating an environment that favoured herding societies with reduced residential mobility living at large sites such as Casa Chávez Montículos (CCM) (Olivera Reference Olivera1991).

Figure 2. Views of the Formative sites included in this study: a) Casa Chávez Montículos; b) Real Grande 6; c) Cueva Cacao 1A.

Later, between 3000 and 1800/2000 BP, herding practices, probably using pens in both the low-lying basin and intermediate gorges (López Campeny Reference López Campeny2001; Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015), were complemented by increased plant cultivation, leading to specialised agricultural practices (Escola Reference Escola2000; Olivera Reference Olivera, Berberián and Nielsen2001) and a closer relationship with the societies in northern Chile, as reflected, for example, in pottery-decoration styles (Olivera Reference Olivera1991; Vidal Reference Vidal2007; Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015). Towards 2000 BP, changes in pottery styles and agricultural developments suggest the establishment of new connections with groups from the nearby mesothermal valleys (Olivera & Vigliani Reference Olivera and Vigliani2000–Reference Olivera and Vigliani2002). Permanent settlements facilitated population growth and the optimisation of agricultural spaces (Escola et al. Reference Escola, Nasti, Reales and Olivera1992–Reference Escola, Nasti, Reales and Olivera1993; López Campeny Reference López Campeny2001), although logistic mobility continued to be dominated by a dynamic sedentism (sensu Olivera Reference Olivera1988) connecting permanent sites with more transient locations for productive hunting and gathering activities (Aschero Reference Aschero and Tarragó2000; López Campeny Reference López Campeny2001; Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Tchilinguirian and Aguirre2002). This change in economic practices signified a shift away from localised activities towards increased mobility and exchange with groups on both sides of the Andes, clearer structuration of space using terraced fields and walled settlements, more sophisticated function-specific lithic and pottery tool technologies, and greater levels of social and political organisation (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015).

Formative sites

CCM is a large tell-like site comprising two levels—inferior and superior—that fall entirely in the Formative period. The lower levels of CCM (CCM inferior) can be dated to c. 2400/2100 BP (Olivera Reference Olivera1991), whereas the upper levels (CCM superior) bear evidence of yet further connections to more diverse Formative cultures in the area. Since 1600/1300 BP, the environment gradually became more arid, and the management of natural resources intensified: innovative strategies for improving agricultural management such as irrigation were introduced, camelids were even more intensively exploited and significant changes in social structure and power hierarchies became more evident (Aschero Reference Aschero, Berenguer and Gallardo1999). Village settlements consolidated, but complementary hunting continued in various micro-environments, with an emphasis on the more humid higher elevations (Olivera Reference Olivera1991; García et al. Reference García, Rolandi and Olivera2000).

The long sequence at the art-rich rockshelter of Cueva Cacao 1A (CC1A), situated in the mountains around the basin, includes layers that were contemporary with the implementation of agriculture and herding, dated to c. 1400/1000 BP. Pot sherds, lithic artefacts, archaeobotanical and faunal remains were found, together with numerous personal ornaments, clothing and tools related to art production (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Vidal and Grana2003). The latter dated to the Formative (c. 5000/3000–1000 BP), Late (1450–700 BP) and Inca periods (fifteenth century), and even to the Spanish conquest (1530 AD) (Aschero Reference Aschero, Berenguer and Gallardo1999, Reference Aschero and Tarragó2000; García et al. Reference García, Rolandi and Olivera2000).

Real Grande 6 rockshelter (RG6) was located in the middle–upper course of the Las Pitas River. Between c. 1200–700 BP, and contemporary with the later occupation of CCM, this area, with its year-round abundance of water and grasses, was used in winter for grazing camelids (Olivera Reference Olivera1991). While the consolidation of herding practices and sedentism occurred in favourable climatic conditions of relative humidity, extensive and intensive modes of hydraulic cultivation (terraces, canals and dams), as well as greater sociopolitical complexity, emerged in more arid environments. Socio-economic changes were also evident in a new conception of space that segregated cemetery areas such as the Casa Chávez necropolis from the main village (Olivera Reference Olivera1991).

The Late period

During the Late period, settlement patterns and associated material culture changed (Figure 3), accompanied by population growth and the material manifestation of territorial claims, evidenced in the high fortified settlements or pukaras (Olivera & Vigliani Reference Olivera and Vigliani2000–Reference Olivera and Vigliani2002; Salminci Reference Salminci2010). New geographically circumscribed sociopolitical units were defined by agglutinated architectural patterns with public spaces, well-defined pottery styles and long-distance camelid caravans (Tarragó Reference Tarragó and Tarragó2000; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Berberian and Nielsen2001; Nuñez Reference Nuñez, Williams, Ventura, Callegari and Yacobaccio2007). An exchange system based on caravans would have facilitated the resources required under this new system.

Figure 3. Views of the Late-period sites included in this study: a) Bajo del Coypar II; b) La Alumbrera.

The development of productive innovations such as pens and terraced fields (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015) also focused on camelid herding and agriculture, triggering unequal social relationships in political organisation (the authority of curacas) and in the distribution and consumption of goods (Tarragó Reference Tarragó and Tarragó2000). Despite these structural inequalities, corporative political formations seem to have played an important role in late Andean societies (see Nielsen Reference Nielsen2006).

Several agricultural fields date to this period, including Punta Calalaste, Campo Cortaderas (Elías Reference Elías2012; Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015) and the village and associated fields at Bajo del Coypar II, an occupation dated to 1000 BP and similar to the Late Belén culture developed in the lowlands (Vigliani Reference Vigliani2001; Pérez Reference Pérez2013). This site, where agriculture was the main economic activity, exemplifies the processes of a population committed to resource gathering and agricultural development in the low basin. Equally typical of this period were settlements built at high-visibility locations, such as the large habitational conglomerate of La Alumbrera on the margins of the Antofagasta lagoon. This settlement, built with local basalt rocks, constituted a large and densely populated residential site, with many structures and tombs, a central sector and two parallel perimeter walls, which may be interpreted as a defensive structure (Olivera Reference Olivera1991; Salminci Reference Salminci2010). Pottery findings also associate it with the Belén cultural system, centred in the Abaucán and Hualfín Valleys (Olivera & Vigliani Reference Olivera and Vigliani2000–Reference Olivera and Vigliani2002; Pérez Reference Pérez2013).

The pottery

The complete assemblage of non-decorated pottery from three Formative sites located in different areas was analysed: CCM (n = 1097), RG6 (n = 80) and CC1A (n = 69). Analytical criteria were based on morpho-functional and low-resolution archaeometric characterisations of pastes, combining firing conditions, fabric texture, colour variation and the nature of the temper used. Clay modelling techniques and wall thickness were also recorded.

Pottery from CCM presented a uniform distribution of medium–coarse granular and fine textures. The latter, characterised by a dense paste, was dominant at the other Formative sites (Table 1). Laminar textures were absent, while some friable elements may have resulted from taphonomic processes. Generally speaking, porosity was observed macroscopically and by testing resistence to mechanical stress among granular-paste sherds, which were friable and contained many inclusions (Vidal Reference Vidal2007). Laminar pastes were frequent during the first occupation of CCM, but notably reduced in the later occupation. They were generally associated with abundant, fine-grained muscovite, or a selection of different, thicker minerals.

Table 1. Characterisation of the sherds from the two periods studied. Two groups were divided in both cases according to the number of fragments: the most frequent association (major sample in each period) and the secondary group (minor sample).

* Small size refers to vessels with openings and height <150mm; medium between 160–300mm; and large >310mm.

Undecorated pottery types from CCM exhibited both exclusively inorganic and mixed (organic and inorganic) inclusions, with a greater frequency of fragments featuring exclusively the inorganic type. At CC1A however, inclusions were inorganic, while at RG6 the opposite was true. Materials used for inclusions were common throughout the assemblages at each site, and ranged from burnt organic matter to various rocks and minerals such as mica, rounded and angular quartz grains, basalt, quartzite and volcanic materials. Material composition was established using X-ray diffraction analyses of local clays and pottery (Olivera Reference Olivera1991; López Campeny Reference López Campeny2001). Inclusions varied in size as well as in composition. Fine grains were dominant, particularly in combination with medium-sized ones. Both CCM and CC1A yielded a few fragments lacking evidence of clear size selection, particularly during later times, and included different kinds of temper, some of which were possibly incorporated intentionally.

Firing conditions varied from site to site. At CCM, both complete and incomplete oxidising conditions were identified, whereas at sites within the gorges, complete reduction or oxidation was most common, with a slight preference for reddish pastes achieved using reduced atmospheres at RG6. This difference may imply the selection of pottery for transportation, based on either aesthetic or material quality, with pottery produced in reducing atmospheres probably regarded as low quality (Vidal Reference Vidal2013). The dominance of black (reduced atmosphere) colours may alternatively have resulted from the frequent use of charcoal when cooking rather than the initial clay-firing process. Pinching and drawing seem to have been the preferred modelling techniques. Differences in wall thickness typical of coiling were noted in sherds with walls between 6 and 7mm thick.

Despite the reduced sherd size recorded at CCM, the sample seemed to include vessels of varying size, with >60% restricted or straight rims and sub-globular bodies, probably pots or pitchers. Some pucos (bowls) and small vessels with straight walls were also present. Most non-restricted openings ranged between 50 and 150mm in diameter, with approximately 100mm being the modal average, and associated with constricted rims and vessels with 6–10mm wall thickness. Necked vessels did not comprise a notable portion of the assemblage.

A similar situation was noted at other Formative sites in the region (Olivera Reference Olivera1991), with a high variability in types and low standardisation of manufacture together with dense and homogeneous pastes and well-fired pots. At Corral Grande (also in the Antofagasta basin), for instance, the similarity with CCM pottery suggested it functioned as a residential base (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015).

The complete ceramic assemblage for the Late-period sites of La Alumbrera (n = 776) and Bajo del Coypar II (n = 548) exhibited stylistic and technological similarities (Pérez Reference Pérez2013). Both samples were dominated by non-decorated materials, mainly porous pastes of medium–coarse texture and with a medium–high density of inclusions. Porous, friable and compact pastes were identified according to the amount, size, type, form and orientation of the inclusions. The former carried a medium–high amount of inclusions (>0.5mm) and featured macroscopically visible cavities resulting from incomplete kneading. Friable textures implied low cohesion, and frequently resulted from abundant inclusions, mainly of mica, a mineral that also caused laminar textures. Compact pastes, with good cohesion and resistance, dominated the fine-textured portion of the assemblages. Potters seemed to prefer thick-walled vessels for the non-decorated group. The average body-wall thickness was 10mm, with a maximum of 18mm recorded at La Alumbrera and 22mm at Bajo del Coypar II.

Regarding form, plain non-restricted vessels (i.e. plates, pots and pucos, or large bowls) were supplemented by simple restricted vessels (urns and pitchers). Pots and pucos tended towards large openings (around 23cm and 20cm respectively) and non-constricted rims, particularly at Bajo del Coypar II, where they accounted for 50% of the assemblage. Together with the limited presence of ash on the external surface, these vessels seemed more compatible for processing, rather than cooking foodstuffs. Pucos would have been appropriate for serving food as well, and urns were generally found in funerary contexts.

Analysis

The role of vessels as containers has long been thought to hold significant implications for changes in society relating to storage, cooking/heating, ceremony and burial, to name just some examples. Consequently, analyses have often focused on the volume and capacity of these vessels, with wall thickness often less prioritised as a metric attribute, despite its importance in conditioning overall vessel form and structure.

Functionally, thickness is mainly conditioned by two variables: vessel size (essentially height) and intended function (Rice Reference Rice1987). When modelling a vessel, walls structurally support the form and the decorative embellishments that affect the final shape. Thicker walls are resistant to mechanical stress, but are not appropriate for vessels that are frequently transported, and their structure may limit content manipulation. Thinner vessels, however, have the advantage of saving caloric energy because of their reduced heating time. Consequently, thin-walled vessels are more appropriate for heating their contents, while thicker pots are preferred for storage and processing (Rice Reference Rice1987; Skibo et al. Reference Skibo, Schiffer and Reid1989).

Although the benefits of thicker walls for vessel structure are evident, a series of technical decisions are also available for modelling large and complex containers, including the choice of techniques (i.e. coiling vs pinching), the larger quantity and better quality of temper and a more thorough control of the firing atmosphere. The discussion presented here focuses on the use of wall thickness to evaluate evolution in pottery traditions between the Formative and Late periods in the Antofagasta de la Sierra basin, and how this related to broader changes in the social landscape. Methodologically speaking, thickness is an easy-to-measure variable, regardless of the quality and size of the fragment being considered. The non-decorated pottery group was selected for consideration due to its frequency in the assemblages and because it seems to be less conditioned by aesthetic designs.

As thickness varies throughout a vessel's structure—particularly in rims and bases—measurements were restricted to vessel bodies. They were taken with hand callipers and statistically processed, noting the mean average thickness, standard deviation and maximum and minimum values (Table 2), presented in the box plot shown in Figure 4. Formative vessels were slightly over 6mm in thickness. In both phases of occupation at CCM, most of the vessels were concentrated around this value. At the remaining two Formative sites, CC1A and RG6, variability was slightly higher, but the mean was similar to the value recorded for CCM as a whole. For the Late period, however, the situation was quite different. Not only were the mean values for vessel thickness at both sites considerably higher, but the range of variation was also greater, indicating that even though vessels generally tended to be thicker, there were many individual pots with similar values to those typical of Formative sherds, as well as a number of pieces with much greater thickness (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of body thickness values for the sherds studied (in mm). The sample includes all the non-decorated fragments recovered in the excavation for the Formative (Casa Chávez Montículos inferior and superior (CCM inf. and sup.); Cueva Cacao 1A (CC1A); Real Grande 6 (RG6)) and the Late period sites (Bajo del Coypar II (BCII); and La Alumbrera (LA)).

Figure 4. Statistical box plot 6v 2121c showing vessel wall thickness at the Formative sites Casa Chávez Montículos (CCM superior and CCM inferior), Cueva Cacao 1A (CC1A) and Real Grande 6 (RG6), and the Late-period sites Bajo del Coypar II (BCII) and La Alumbrera (LA) (mean; box: mean±SE; whisker: mean±2*SD). Note the larger range for the Late period as well as the higher mean thickness values, particularly in relation to CCM.

Discussion

Statistical diachronic comparison of body-wall thickness among the complete non-decorated assemblage showed coherent variation over time, most notably indicating the appearance of a new technological strategy in the Late period. Wall thickness may, among other factors, be conditioned by the intended size of the vessel. In the case of the analysed pottery, this relationship was quite strong, as with few exceptions, wall thickness for small- and medium-sized vessels measured <8mm, whereas the largest ones were >9mm thick (Vidal Reference Vidal2007; Pérez Reference Pérez2013). This relationship may only be regarded as linear, however, when other variables affecting thickness (e.g. type, amount and size of temper or modelling techniques) were maintained as constant. In order to identify the relevant variables, a simplified châine opératoire was proposed for each period (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Châine opératoire for the Formative and Late periods. The red area highlights the development of a second strategy for storage vessels in later times.

Conservativism in production technique and decoration is frequently mentioned for pottery production from many periods (e.g. Rice Reference Rice1987). Resistance to innovation implies that technology and materials remain largely unaltered in time. Such behaviour may be particularly useful for populations inhabiting poor environments with significant fluctuation in resources (Camino Reference Camino and Carballido2004), as suggested by Fernández's (Reference Fernández1999) ethnoarchaeological and experimental research with potters from Laguna (Jujuy). The fact that pottery manufacture is generally a conservative tradition does not necessarily imply that it is invariable in the long term. As a cultural practice, technological traditions are a consequence of, and contributor to, specific contexts of production and use, in both their physical manifestation and the social role its production played. Alterations in this dynamic might force potters to change an otherwise routine process.

When considering pottery-making during the Formative and Late periods in Antofagasta de la Sierra, several changes were evident in production methods. Different styles were believed to derive from exchange (although it is unclear whether this related to ideas, people or actual pottery) with groups from different areas. They do not, however, explain the significant increase in wall thickness. Indeed, most imported vessels in the area had relatively thin walls. During the Formative, the difference in thickness between non-decorated and decorated vessels was insignificant, but in the Late period, the deviation of the range was more variable. Materials copying foreign styles (i.e. Belén, Santa María and Incan styles) exhibited differing thicknesses, despite their probable localised production (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015). Descriptive statistics for Bajo del Coypar II and La Alumbrera indicated an average thickness of 10.25mm and 9.46mm respectively, significantly lower than the values for non-decorated materials (Pérez Reference Pérez2013).

Revision of the main châine opératoire corresponding to each period (Figure 5) suggests alternative explanations for varying thickness. From the five main stages considered (i.e. raw material extraction, raw material processing, modelling, decoration and firing), only decoration did not include technical variations besides thickness, indicating an intimate relationship between technological factors and the potters’ decisions when creating a vessel, regardless of potential changes in symbolic value.

Textures were more variable during the Late period than during the Formative, probably due to different processes, including raw material selection, treatment and kneading. Whereas in the Formative, inclusions may have occurred naturally within the clay, in the Late period, the basic matrix was complemented with larger, more angular inclusions. Although they came from local rocks, their collection would have implied changes in the extraction strategy, with greater time investment and a more thorough knowledge of the surrounding landscape and the materials used.

During the Formative, temper selection would have required a complex treatment process too. Finer granulometries may have entailed the extraction of undesired elements by hand or through grinding (mortars and pestles were common) as part of a concerted effort to homogenise paste, integrate materials and release air bubbles. This matrix was later modelled following two alternative techniques: most small/medium-sized vessels were made by pinching, whereas coiling marks were observed on larger vessels. These two modelling strategies imply significant differences in the technical gestures and the physical effort needed in the manufacturing process. Pinching is a rather simple technique, involving a single stretching process, whereas coiling entails a succession of minor stages. As a technique, coiling allows potters to model diverse morphologies. In the Late period, coiling was identified among a number of larger vessels; pinching was also observed.

Differences were similarly noted in the firing processes. At the beginning of the Formative, most of the sherds indicated mixed or reducing conditions, with few oxidised pieces. The absence of oxidising materials may well indicate that either these vessels were fired in domestic hearths with limited control over the process, or that they were affected by later depositions of carbon particles (Olaetxea Reference Olaetxea2000). During the Late period, however, the representation of oxidised fragments drastically increased, suggesting the use of larger firing structures specifically designed for better oxygen circulation. Significantly, while thicker vessels were completely or partially fired with an oxidising flame, the remaining sherds showed greater irregularity in treatment.

These variations in the châine opératoire demanded a revision of the traditional strategies or at least some flexibility in knowledge transference procedures to allow for innovation. Furthermore, either a larger number of agents or an intensified activity would have been needed to cope with the greater labour-time investment and the specific knowledge required. It could be argued that this constituted a ‘formal specialisation’, defined by the transition from a communal domestic technology to one in which the acquisition of knowledge allowed the modification of pre-existing châines opératoires and end products. Consequently, the increase in wall thickness may indicate the need for a specific kind of vessel that demanded significant changes in pottery-making, from raw material extraction, to firing.

This contradicts the idea of a conservative technology that reproduces long-entrenched manufacturing patterns. The châine opératoire during the Late period was much more varied than in the Formative, indicating particular production techniques used to achieve a more diverse range of end products, and fulfil changes in the economic and social needs of the potters’ group. The introduction of these new modes of manufacture would have probably triggered changes in the social context of pottery production.

In Antofagasta de la Sierra, there was a drastic restructuring of space coinciding with these changes in pottery manufacture, defined by the configuration of a new social landscape: from villages adapted to the availability of resources (i.e. Casa Chávez Montículos), to settlements spatially structured to incorporate agricultural fields (Bajo del Coypar; La Alumbrera). It also coincided with a predominantly arid environmental phase that started around 1300/1200 BP (Tchilinguirian & Olivera Reference Tchilinguirian, Olivera, Korstanje and Quesada2010).

This seems to indicate that, in view of these environmental changes, local groups decided to introduce several technological strategies to produce the resources that they needed rather than relocating their settlements or reducing their population (Tchilinguirian & Olivera Reference Tchilinguirian, Olivera, Korstanje and Quesada2010). It would explain the agricultural systems that developed in the Late period, which coincided with the time of greatest aridity. Terraces, canals and dams seemed to have been built as a response to a growing intensification of production to face the scarcity of resources brought about by climatic change. Drastic but gradual changes in wild flora availability were recorded in the area, which were matched by the increase in domestic crops (Grana Reference Grana2013; Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Escola, Elías, Pérez, Tchilinguirian, Salminci, Pérez, Grana, Grant, Vidal, Killian, Miranda, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015).

Pottery production, as a component of daily life, was affected by these changes. At the end of the Formative (CCM superior), thicker vessels of oxidised firing began being produced. In the Late period, this practice was consolidated, with at least some of the ceramics being linked to processing activities and the storage of agricultural produce due to the formal and mechanical properties and use-wear patterns identified in certain vessels (Vigliani Reference Vigliani2001; Pérez Reference Pérez2013), using large vessels of quite thick walls. In the pottery from Bajo del Coypar II, however, friable pastes were the dominant type (50% of the sample), whereas at La Alumbrera they represented just 19% (Pérez Reference Pérez2013). Friable pastes would not have been a drawback for large storage vessels, but they could have seriously impaired the durability of a pot intended for constant domestic use. It should be noted that the dual nature of La Alumbrera (habitat and agricultural site) increased the range of functions pottery may have fulfilled.

Functional analysis of larger thick-walled vessels based on morphology and mechanical performance indicated their suitability for long-term food storage and its drying for preservation (Vigliani Reference Vigliani2001; Vidal Reference Vidal2007; Pérez Reference Pérez2013). Further discrimination between functions is, however, possible: large thick vessels of porous and compact pastes are appropriate for processing activities involving high physical stress such as grating, grinding and chopping (Bronitsky Reference Bronitsky1986). Friable pottery, resulting from abundant mica-rich inclusions and exposure to incomplete firing, could represent an advantage for storage because the pots are more resistant to humidity, helping to preserve the vessel's contents from decomposing. This would be a significant advantage in the Puna environment with extremely variable humidity levels in its different microenvironments. Furthermore, poor wall consolidation would not have affected vessel performance in static storage.

When considering these propeties with regard to the agricultural site of Bajo del Coypar II (Olivera & Vigliani Reference Olivera and Vigliani2000–Reference Olivera and Vigliani2002), it may be deduced that the more dominant friable pottery was devoted to storage, whereas the harder and thicker vessels better represented at La Alumbrera could have been used to process grain or similar foodstuffs (Pérez Reference Pérez2013). These vessels were very rare at CCM, and indeed were non-existent at contemporaneous sites, where agricultural products were almost negligible (Vidal Reference Vidal2007).

Assemblage variability can be similarly informative when considering each site individually. As already mentioned, CCM was a residential base, with evidence of production and consumption at the site, while CC1A was a multi-functional rock art site that also held ritual significance (Olivera et al. Reference Olivera, Vidal and Grana2003). Evidence from RG6, on the other hand, attested to engagement in a complementary hunting-herding strategy. In the latter two sites, their transitory but recurrent use probably limited the need for vessels designed for storage. Consequently, the entirety of the sample was defined by high-quality materials, suggesting a preference for ceramics with a long use-life in response to the risk of not being able to replace them until they returned to the residential base where they were produced (Vidal Reference Vidal2013).

For the Late-period sites, although thick-walled pottery was common at both the locations studied, textural differences between the assemblages may reflect the way in which they were used: the dominance of vessels suitable for storage at Bajo del Coypar II seem to have been most appropriate for working this agricultural field, while the inhabitants of La Alumbrera, a more complex site that included both agricultural and domestic structures, would have demanded a larger variety of vessels for their daily activities, resulting in overall lower wall-thickness values.

Different explanations for change in pottery thickness have been forwarded: at the site of Matancillas (Salta), reduced wall thickness was suggested as a strategy to save fuel for cooking food (Camino Reference Camino and Carballido2004; Muscio Reference Muscio2004). That approach would minimise the costs for processing staples such as maize and quinoa in an environment where fire fuel could be scarce, and may have been a factor in the development of, and preference for, this technological trend.

The prevalence of thick-walled vessels among Late-period assemblages seems, however, to undermine this theory. Evidently, the scarcity of fuel and low oxygen levels in the Antofagasta de la Sierra Puna environment did not discourage the production of large thick containers, convenient for storing and processing agricultural foodstuffs. This did not mean, however, that local populations were unaffected by environmental conditions. On the contrary, the adoption of new settlement and landscape strategies at the end of the Formative, further consolidated in the Late period, suggested that there was some upheaval relating to this shift. In this case at least, however, pottery modification did not seem to have been an environmental adaptation, but part of a cohesive cultural process, evidenced in the change of the structure and function of sites, as well as in other artefacts and materials, suggesting the orientation of a completely new lifestyle. It implied the revision of traditional techniques and strategies for the pottery-making process to complement the production of small- and medium-sized, thin-walled vessels—probably made from unmodified clays with a carefully applied finish and through incomplete firing—with a more diversified assemblage featuring a higher presence of thick-walled vessels. This would have required a change for the entire process of manufacture, from raw material extraction to the use of a firing method that afforded greater control and refinement.

Conclusions

In any society or environment, production decisions and technology are related through tradition and cultural norms. Consequently, it was expected that pottery-making during the transition from the Formative to the Late period in Antofagasta de la Sierra would follow a large-scale societal change, resulting in an increase of medium/large archaeological sites, concomitant demographic growth and improved agricultural and herding practices. As already noted, from c. 1000 BP, the regional economy was dominated by agriculture and organised in large field systems segregated from the domestic villages.

The growing aridity would have probably placed significant stress on fuel procurement. As a society of herders, camelid droppings may have been a potential resource with which this could have been supplemented. The functional difference between vessels used for storage and processing may also have been influenced by restrictions of fuel availability. Strong and cohesive pastes were used for vessels intended for processing, and were improved upon by the use of controlled firing. This quality was not so essential for the production of storage vessels. On the contrary, the larger number of inclusions and low cohesion of pastes would have made them more resistant to changes in humidity. Thus a distinction could be made between a strategy that would have devoted more caloric energy exclusively to processing vessels, and one where storage vessels were fired at lower temperatures for a shorter time, something that was reflected by the contrast in paste quality. The difference in the representation of both kinds of vessels indicated that processing activities were more frequent at La Alumbrera, being at once a production centre and living space, whereas storage vessels were found close to the exclusively agricultural settlement of Bajo del Coypar II.

It may be concluded that human behaviour and processes of cultural change at Antofagasta de la Sierra were consequences of the ecological and social environments. The aforementioned environmental changes seemed to have stimulated or at least coincided with the implementation of both intensive and extensive agricultural and herding strategies, whereas changes in pottery technology were a consequence of a decision that accompanied this economic development. Potters underwent a period of trial and error in the development of new production strategies, accommodating existing knowledge with new factors affecting design and creation. As an innovative technology with specific requirements, this shift in pottery production brought about changes in social organisation and conditioned the creation of new identities, which, over time, resulted in new strands of craft specialisation and divisions of labour.