Introduction

The Qin Empire (221–207 BC) marked the beginning of Chinese imperial history. The unification of China and subsequent economic, cultural and political reforms initiated by Qin Shihuang (259–210 BC), the first emperor, had far-reaching effects on the consolidation and evolution of state infrastructure through the following millennia (Lewis Reference Lewis2007; Portal Reference Portal2007; von Falkenhausen & Shelach Reference von Falkenhausen, Shelach-Lavi, Pines, Shelach-Lavi, von Falkenhausen and Yates2013; Shelach-Lavi Reference Shelach-Lavi2015). The early history of the Qin people, as documented in Chinese historical texts such as the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), records their expertise in horse husbandry (Guo Reference Guo1985; Jiang Reference Jiang2001). Moreover, the expansion of the Qin State—the predecessor of the Qin Empire—and Qin Shihuang's eventual military triumph over the other ‘Warring States’ were also, in part, the result of the skill and strength of Qin cavalry (Sun Reference Sun1996; Yates Reference Yates and Portal2007; Kelekna Reference Kelekna2009). Terracotta horses recovered from the burial pits at Qin Shihuang's mausoleum support the inference that mounted horseback riding had become an important aspect of military strategy by the late first millennium BC (Yuan Reference Yuan1990; Ledderose Reference Ledderose2000; Yates Reference Yates and Portal2007; Duan Reference Duan2011). The crucial role of horses in the Qin period is further demonstrated by the inclusion of horses in the mortuary contexts of the Qin elite. Excavations across the present-day provinces of Gansu and Shaanxi in north-western China have documented zooarchaeological remains from pits containing horses and chariots associated with burials of the Qin royal families and lower-level elites (e.g. Yun Reference Yun1984; Shang & Zhao Reference Shang and Zhao1986; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Li, Zhao and Wang2002; Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Mao and Zhao2005; Zhang & Ding Reference Zhang and Ding2008; Tian et al. Reference Tian2013; Cai et al. Reference Cai2018; Cao et al. Reference Cao, Geng and Hu2018; Hou Reference Hou2018). Numerous accessory pits containing horse skeletons have also been discovered within Emperor Qin Shihuang's mortuary complex (Qin Terracotta Warriors Archaeological Team 1980; Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology & Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum 2000).

Previous research into chariot-horse/horse pits of the Qin period has focused primarily on the configurations of the horse and chariot assemblages and their socio-political implications (Zhang Reference Zhang and Yuan2000; Zhao Reference Zhao2011; Wu Reference Wu2013). Understanding of the criteria used to select the animals included in these mortuary practices, however, is limited—especially for those burials associated with the highest social levels in Qin society. To date, only sparse age and sex data from horse skeletons from Qin elite mortuary contexts have been reported (Zhang & Ding Reference Zhang and Ding2008; Cao et al. Reference Cao, Geng and Hu2018) and there is little information on the height of the horses.

Here, we present a zooarchaeological analysis of horse skeletons from K0006, an accessory pit in Emperor Qin Shihuang's mausoleum. We examine the age, sex and height of these horses to evaluate their selection criteria and, by extension, the wider significance of horses in Qin society, including husbandry practices, horse breeds, and their military and symbolic importance.

Accessory pit K0006

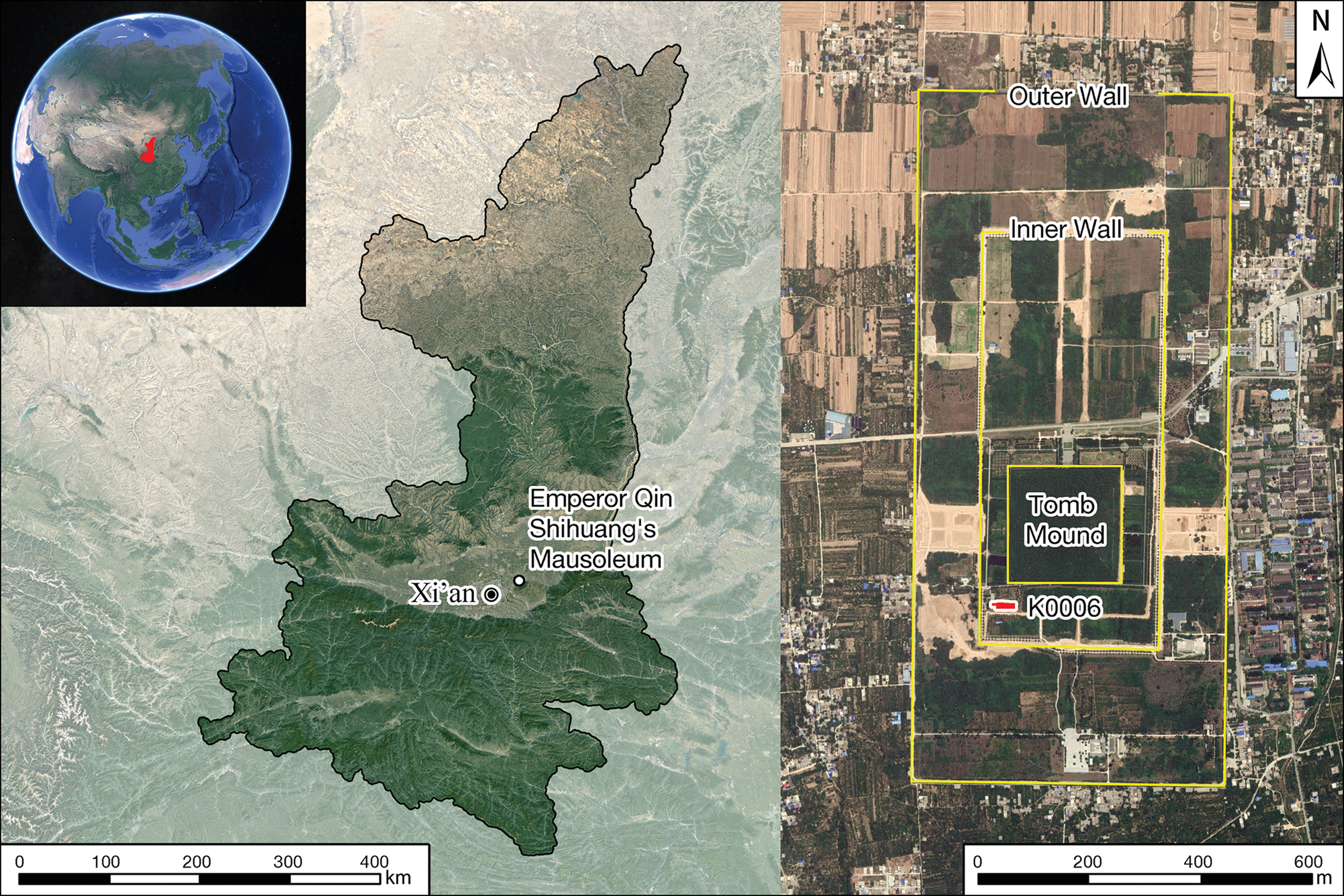

Emperor Qin Shihuang's mausoleum (34°22´39.2″N, 109°15´36.7″E) is located in the Lintong District of Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, approximately 4km north of the Lishan Mountain and 36km east of Xianyang, the location of the Qin Empire's capital. Pit K0006 lies in the ‘inner city’ section of the mortuary complex, to the south-west of the main burial mound of Qin Shihuang (Duan Reference Duan2002, Reference Duan2011) (Figure 1). Two fieldwork seasons in 2000 and 2013, directed by Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum, revealed that K0006 covers an area of approximately 410m2 and includes a ramp and front and rear chambers (Figure 2; see also Figure S1 in the online supplementary material (OSM)). The chambers contained different items and were physically connected, but not aligned along an axis. While 12 terracotta human figures and a single-pole wooden cart were positioned in the front chamber, the horse remains were recovered from the rear chamber. Traces of wooden frameworks, including shelf boards, ground boards and wall boards, were also identified in the two chambers. Although the precise significance of K0006 remains unclear, it is widely accepted that it belongs to a context symbolising one of the central administrative offices of the Qin Empire (Duan Reference Duan2002; Yuan Reference Yuan2002; Chen & Zhao Reference Chen and Zhao2014).

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Emperor Qin Shihuang's mausoleum in China and accessory pit K0006 within the mortuary complex (figure by Y. Han).

Figure 2. Accessory pit K0006 on exhibition. Looking east down the entrance ramp to the front chamber, where some of the restored terracotta human figures are displayed, and the rear chamber, with the horse remains behind (photograph by L. Wu).

Materials and methods

Part of the K0006 horse bone assemblage excavated in 2000 has been previously analysed (Yuan Reference Yuan2006). In the present study, we re-examine that assemblage, along with further horse remains uncovered in 2013 (Figure 3). Preservation conditions in K0006 were not ideal due to repeated historical flood damage (Duan Reference Duan2002). Furthermore, because of the intention to conserve and exhibit the remains in situ, not all skeletal elements were completely exposed; we were therefore limited to recording only the visible bones. Following standard protocols (e.g. von den Driesch Reference von den Driesch1976), we measured fully exposed and well-preserved skeletal elements in their anatomical positions. Here, we estimate the ages of the animals using bone epiphyseal fusion, dental eruption and incisor wear (Silver Reference Silver, Brothwell and Higgs1969; The Chinese People's Liberation Army University of Veterinary Medicine 1979). Sex estimation is based on the presence or absence of well-developed canines and the morphology of the pelvis (Sisson Reference Sisson1953).

Figure 3. Photograph showing the excavation of K0006 in 2013 (taken looking east), with archaeologists working in the rear chamber (photograph by L. Wu).

We calculate the heights of the animals measured to the withers (Xie Reference Xie1991) using methods developed by Kiesewalter (Reference Kiesewalter1888), Hayashida and Yamauchi (Reference Hayashida and Yamauchi1957) and May (1985). Corrected multiplicative coefficients proposed by May (1985) were based on ranges of withers heights originally described in Vitt (Reference Vitt1952). We use the major limb bones for calculation because previous research has indicated that withers heights deduced from smaller skeletal elements are less reliable (Hayashida & Yamuchi Reference Guo1957; von den Driesch & Boessneck Reference von den Driesch and Boessneck1974). In addition, we conducted one-way ANOVA and pairwise t-tests to compare the estimated heights of horses from K0006 with those from four earlier sites pre-dating the Qin Empire. Statistical tests are conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 software.

Results

Positioning of horses in K0006

All horse forelimbs in K0006 were in an orderly arrangement, with some skeletal elements superimposed (e.g. with ulna and radius beneath the humerus), suggesting that the legs of at least some of the horses may have been bound upon inhumation. The orientation of the heads varied due to post-depositional disturbance (Figure 4). Although taphonomic factors make it challenging to assign every skeletal element to a specific animal, identification of the major skeletal elements visible permits determination of the minimum number of individuals (MNI) (Table 1). The 24 pelvises identified suggest that K0006 contained at least 24 horses, which may be divided into six possible groups (Groups I–VI), according to the spacing between these animals. All the horse skeletal elements, except for the skulls and a few cervical vertebrae, appear to have been stacked in alignment in the southern part of the rear chamber. This was more evident in Groups II–V. It is likely that an east–west partition made of perishable material was set up in front of the horse forelimbs.

Figure 4. The arrangement of horse skeletons in K0006. These animals were probably laid in groups upon inhumation, as is evidenced by the intervals between them (shown as dashed lines in the figure) (figure by Y. Han).

Table 1. MNI* of the major skeletal elements for the six groups of horses in K0006.

* We recorded the number of visible bones for both sides and used the larger number to represent the MNI of each skeletal element.

Sex and age estimation

Six crania, 12 mandibles and 11 pelvises are sufficiently preserved for sex estimation. None of these elements exhibit clear female characteristics. Developed canine teeth from all crania and mandibles indicate male horses. All pelvises exhibit a lesser degree of obliquity, robust pubic tubercles and a wider ischiatic arch, all of which are distinctly male features (Sisson Reference Sisson1953). For the eight pelvises from K0006 where the transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet can be measured, the mean value is 176.1mm (160–200mm; standard deviation = 16.7). This is much smaller than the mean value for female horses but close to that for males, given that the average transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet is approximately 230–240mm for females and 200mm for males (Sisson Reference Sisson1953). The spatial relationships of these specific skeletal elements suggest that they represent 16 individual animals. Taking these data together, we therefore infer that at least 16 of the 24 horses in K0006 were male. More specifically, Groups I and II each contain at least three males, Groups III, IV and VI contain at least two males, and all Group V horses are male. In short, all horses in K0006 where sex can be estimated are male.

One complicating issue associated with sex estimation in horses is castration, as this can affect the relative size of male animals. This practice, for example, is documented among horses from burials of the Pazyryk Culture in the Altai Mountains during the late first millennium BC (Vitt Reference Vitt1952; Sisson Reference Sisson1953; Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970; Lepetz et al. Reference Lepetz, Debue, Batsukh, Pankova and Simpson2020). The absence of testicles on terracotta traction horses in the Terracotta Army Pit No. 1 has been noted (Yuan & Flad Reference Yuan and Flad2003; Yuan Reference Yuan2006), and we therefore cannot exclude the possibility that some of the male horses in K0006 were geldings.

Seven crania and 12 mandibles were available for dental analysis. The spatial relationship between these crania and mandibles suggests that they represent a minimum of 12 horses. All teeth are permanent teeth (Figure 5). Dental wear of the lower incisors suggests approximate ages of 9–10 (n = 4), 10–13 (n = 5) and >10 years old (n = 3) (see Table S1). None of these horses was younger than nine years old at death, and nearly three quarters were slightly older than 10 (Figure 6). The dental wear age estimates are corroborated by bone epiphyseal fusion, which shows that all fully exposed skeletal elements are fused—that is, these horses died after five years of age.

Figure 5. Examples of horse mandibles and crania from K0006 (photograph by Y. Li).

Figure 6. Age composition of horses from K0006 based on incisor wear from mandibles available for analysis (figure by C. Zhang).

Height

Bearing in mind that not all skeletal elements were completely exposed and sufficiently well-preserved for measurement, and that we are unable to assign every bone to a specific individual, we estimate the heights of the horses from the available limb bones and then calculate the mean value of these estimates. The withers heights, based on three different methods of calculation, are broadly consistent. The mean height of horses from K0006 is 1.405–1.424m (or 14 hands), with an average of 1.414m (Table 2; for the data on each measured skeletal element, see Table S2).

Table 2. Estimated stature of horses in K0006. MEH = mean estimated height.

Discussion

Where possible, sex estimation has shown that the horses from K0006 were male. This fits into the wider ancient Chinese pattern of interring predominantly male horses in chariot-horse/horse pits associated with elite burials during the late second and first millennia BC (Table 3). This is also the case for contemporaneous elite burials found in modern-day Mongolia and Central Asia (Fages et al. Reference Fages, Seguin-Orlando, Germonpré and Orlando2020; Lepetz et al. Reference Lepetz, Debue, Batsukh, Pankova and Simpson2020). The preference for male horses in mortuary contexts may be a result of specific husbandry practices, such as keeping females for reproduction. It is also likely that males were more frequently used for traction or riding, and may have served a similar symbolic purpose in the afterlife of the elite.

Table 3. Sex of horses from mortuary contexts in Bronze Age China. WZ = Western Zhou (c. 1050–771 BC); SA = Spring and Autumn (770–476 BC); WS = Warring States (475–221 BC).

* The numbers in parentheses refer to horses with available sex data.

The mean age at death of the horses from K0006 appears to be approximately 10 years. While the prime age of horses depends on various factors (e.g. breed, management strategies and type of work), horses are considered to be in their prime between 5 and 12 years old, or an even narrower age range (Collins & Hallam Reference Collins, Hallam and Thompson1983; Marth Reference Marth1998; Myers Reference Myers2005). In a recent ethnographic review, for example, modern pastoralist families in northern Inner Mongolia, in China, indicated that the prime age for their horses was approximately 8–12 years old (Li, X. et al. Reference Li, Li, Zhang and Liu2020). With no juveniles and most individuals with age estimates falling in the upper range of prime age, our data suggest that the horses interred in K0006 were well-selected animals in their prime.

Comparing these results with published datasets from chariot-horse/horse pits affiliated with late Shang- and Warring States-period (c. 1350–221 BC) elite burials (mostly in the Yellow River Valley of northern China) gives additional insights into the selection of horses for Qin Shihuang's mausoleum. Prior to the Qin Empire, horses younger than nine years of age appear to have dominated the assemblages from chariot-horse/horse pits associated with the elite class (Figure 7). This may also be the case for Yujiawan (Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 2009) and Shenheyuan (Zhang & Ding Reference Zhang and Ding2008), although the ages of only five horses from these two sites could be estimated. The only exception appears to be the site of Chongpingyuan: while two of the four horses from this site were 11–12 years old, the other two were simply described as ‘adults’, without specific age estimates (Li et al. Reference Li, Ding and Song2018). Despite a more restricted age range at Zhaitouhe, Chongpingyuan and Shenheyuan, the age range of horses in all other cases is much wider, with assemblages containing very young and/or old animals. This phenomenon is also observed in many regions outside the Yellow River Valley during the first millennium BC, such as in Mongolia, Kazakhstan and the eastern Tianshan Mountain region of north-western China (Lepetz et al. Reference Lepetz, Debue, Batsukh, Pankova and Simpson2020; Li, Y. et al. Reference Li, Li, Zhang and Liu2020).

Figure 7. Boxplot illustrating the age structures of horses from chariot-horse/horse pits pre-dating the Qin Empire, based on published data (for citations, see Table 3). Only assemblages containing at least four individuals with age information were included. Where the age was described as a range in the original publication, we used the arithmetic mean value to represent the age (e.g. 9 for “8–10” and 11.5 for “10–13”). Since we could not give a mean value for three horses from K0006 identified as “above 10 years old”, these data are not included here (WGC = Wuguancun; ZSGN = Zaoshugounao; XG = Xiguan; JWG = Jiwanggu; JSC = Jinshengcun; MJP = Maojiaping; LY = Luoyang; ZTH = Zhaitouhe; YJZ = Yanjiazhai) (figure by C. Zhang).

Although horses from Maojiaping (Liu Reference Liu2019), Yanjiazhai (Cao et al. Reference Cao, Geng and Hu2018) and Shenheyuan were associated with elites or royal members of the Qin State, the social status of the deceased was not comparable to that of Emperor Qin Shihuang. This implies that the age of the horses may have been a critical parameter in their selection in Qin mortuary practices: specifically, the interment of older horses of prime age, in a more restricted age range, may have been exclusive to individuals of the highest status. Detailed zooarchaeological study of further cases may provide additional insights into this question.

Height was crucial to evaluating the quality of a horse in Qin society. Qin bamboo texts recovered from the site of Shuihudi in southern China document that horses recruited for military purposes must be taller than 5.8 chi, and the officials in charge would be penalised if this standard was not met (Processing Team of the Shuihudi Qin Bamboo Texts 1978). Previous research suggests that one chi was approximately 0.231m during the Warring States and Han periods (Qiu Reference Qiu1992). If height as described in Qin bamboo texts refers to withers height, then military horses would have been at least 1.34m tall. The terracotta mounted horses in the Terracotta Army pits of Qin Shihuang's mausoleum, albeit not real, average 1.385m in height (Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology & Archaeological Team of the Terracotta Army Pits of the Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum 1988), indirectly indicating the quality of horses required by the Qin army. While taller horses may not necessarily have provided an additional advantage in chariot warfare, they may have been preferred for mounted combat, as they provided greater visibility and a longer stride, the latter allowing them to cover more ground. Most horse vertebrae from K0006 were either not fully exposed or were superimposed by other bones, and therefore unavailable for analysis. Of the few vertebrae in Groups II and V that could be observed, we identified discernible osteophytes (bone spurs) on three lumbar and lower thoracic vertebrae. Vertebral abnormalities on horses can be caused by various factors, such as congenital defects, ageing and biomechanical forces (Rooney Reference Rooney1997; Jeffcott Reference Jeffcott1999). Pathologies affecting the lumbar and lower thoracic vertebrae are likely to be associated with use for transport (Levine et al. Reference Levine, Whitwelle and Jeffcott2005; Li, Y. et al. Reference Li, Li, Zhang and Liu2020), suggesting that at least some of the horses from K0006 were used for riding or traction. While we do not know whether the K0006 horses had previously served in military contexts, their estimated mean height of 1.405–1.424m makes them animals of high quality during Qin Shihuang's time.

Applying the same methodology here as in published measurements of major limb bones, we calculate (or recalculate) the heights of horses from chariot-horse/horse pits at four sites pre-dating the Qin Empire: Heishuihelu (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Xia, Yuan and Yang2009), Zaoshugounao, Luoyang and Zhaitouhe (see Table S3). Given that horse limb bones normally fuse at 3.5 years of age (Silver Reference Silver, Brothwell and Higgs1969), we do not assess younger animals. When compared, horses from K0006 appear taller than their pre-Qin counterparts: all three calculation methods reveal that horses from these earlier sites were, on average, shorter than 1.40m (Table 4; Figure 8). A one-way ANOVA test (F = 4.490, p <0.01, with 4 and 23 degrees of freedom) suggests that the horses’ heights, according to Hayashida and Yamauchi's (Reference Hayashida and Yamauchi1957) method, are statistically different across the five sites. Post-hoc multiple comparisons (Least Significant Differences, LSD) further indicate differences between K0006 and the other four sites (Table S3). With respect to the heights derived from May's (Reference May1985) method, the one-way ANOVA test (F = 5.747, p <0.01, with 4 and 21 degrees of freedom) suggests that the horses’ heights are, again, statistically different. Post-hoc multiple comparisons (LSD) demonstrate that the mean height of K0006 horses is statistically different from the mean height of horses at Zaoshugounao Zhaitouhe and Luoyang (Table S3).

Figure 8. Boxplots showing the mean height of horses from five sites, calculated using three different methods. Each dot represents the mean value for each skeletal element used for calculation (HSHL = Heishuihelu; ZSGN = Zaoshugounao; LY = Luoyang; ZTH = Zhaitouhe) (figure by C. Zhang).

Table 4. Height estimates for horses from chariot-horse/horse pits. WZ = Western Zhou (c. 1050–771 BC); SA = Spring and Autumn (770–476 BC); WS = Warring States (475–221 BC); MEH = mean estimated height.

Breed of horse is a significant factor affecting animal height. Common breeds with a long history of use for transport in northern China, such as Mongolian horses, are not known for their height (Institute of Animal Sciences at Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences 1986; Xie Reference Xie1991). While the taller individuals of such breeds may have been selected for burial with Qin Shihuang, it is also possible that taller breeds were imported from other regions. Indeed, tall horses have been found in late first-millennium BC elite burials of Central Asia (Francfort & Lepetz Reference Francfort, Lepetz, Gardeisen, Furet and Boulbes2010). Chinese historical texts also record that quality horses were sought from Central Asia, such as the ‘blood-sweating’ or ‘heavenly’ horses (Waley Reference Waley1955) that were known for their conformation, speed and endurance. Although the pursuit of such horses is normally associated with the Han emperors (Waley Reference Waley1955; Creel Reference Creel1965; Cooke Reference Cooke2000), it is possible that tall, high-quality horses were introduced earlier to the Chinese heartlands (Cai et al. Reference Cai2018). This may explain the height of the K0006 horses. Regardless, the breeds of the horses in Qin Shihuang's mausoleum, and the potential economic and cultural exchanges behind their acquisition, will remain unknown until direct genetic evidence and further archaeological information come to light.

The construction of Qin Shihuang's mausoleum was an unprecedented project. Standing at the apex of the Qin mortuary system, its organised construction, ritual furnishing and efficient logistics are all visible in the layout of the mortuary complex and the manufacture of terracotta figures and bronze artefacts for inhumation in the Terracotta Army pits (Duan Reference Duan2011; Martinón-Torres et al. Reference Martinón-Torres2011, Reference Martinón-Torres2014; Li et al. Reference Li2014, Reference Li2016; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Zhang and Li2017, Reference Quinn2020). Specially selected horses and their positioning in orderly groups in K0006 make this accessory pit another example of specific planning within the complex.

Conclusion

The selection and use of horses in elite mortuary contexts is crucial to understanding the military, economic and symbolic significance of a key domesticated animal species, as well as the development of mortuary rituals and social hierarchy in early imperial China. Our zooarchaeological study of accessory pit K0006 in Emperor Qin Shihuang's mausoleum shows that the horses included in this highest-level Qin mortuary context were selected for their sex, age and height: they were tall, adult male animals. Prior to their selection to accompany the emperor into the afterlife, these animals may also have been used for transport (either riding or traction). Our findings reinforce the picture derived both from ancient texts and from the archaeological investigation of other mortuary contexts that emphasise the significance of horses to Qin political and military authority, and the role of these animals in conceptions of the afterlife in early imperial China.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum for support in this research. We are grateful for insightful feedback from Rowan Flad on early drafts of this article, and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Funding statement

This research was supported, in part, by the National Social Science Fund of China (18CKG024) and the Professional Support Program for Excellent Young Scholars of Northwest University.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.72