Introduction

Donkeys (Equus asinus) have played an important role as beasts of burden for thousands of years. Driving the expansion of ancient trade routes, donkeys were also relied on by travellers, pastoralists and farmers for transport and traction. Unlike horses, donkeys have seldom been used for warfare, elite display or entertainment (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Grant, Choyke and Bartosiewicz2006; Marshall Reference Marshall, Denham, Iriarte and Vrydaghs2007; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2018). The earliest donkeys were domesticated c. 4000–3000 BC from desert-adapted African wild asses (Equus africanus) and served as pack animals (Rossel et al. Reference Rossel, Marshall, Peters, Pilgram, Adams and O'Connor2008; Shackelford et al. Reference Shackelford, Marshall and Peters2013; Rosenbom et al. Reference Rosenbom, Costa, Al-Araimi, Kefena, Abdel-Moneim, Abdalla, Bakhiet and Beja-Pereira2015). Commonly used before horses in Mesopotamia and Egypt (Shev Reference Shev2016), donkeys, like boats, were considered so valuable to commerce that an early Egyptian king ceremonially buried ten donkeys in his mortuary temple at Abydos to ensure their presence in his afterlife (Rossel et al. Reference Rossel, Marshall, Peters, Pilgram, Adams and O'Connor2008). Donkeys served transport needs and, at times, filled ceremonial roles on trade routes in the Bronze and Iron Age Levant (Greenfield et al. Reference Greenfield, Shai and Maeir2012; Bar-Oz et al. Reference Bar-Oz, Nahshoni, Motro and Oren2013; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2018). The Greeks and Romans spread the use of donkeys as transport animals through parts of Europe and Western Asia (Hanot et al. Reference Hanot, Guintard, Lepetz and Cornette2017). In China, modern donkeys are genetically diverse and of African origin (Han et al. Reference Han2014), yet they do not appear in Neolithic (c. pre-4000 BP) faunal assemblages (Liu & Ma Reference Liu, Ma, Albarella, Rizzetto, Russ, Vickers and Viner-Daniels2017); little is known about their expansion into East Asia, or about their local roles through time.

Ancient texts in Shiji Xiongnu Liezhuan (史記•匈奴列傳), a chapter in the earliest Chinese historic literature, suggest that donkeys were used as pack animals by the Xiongnu (匈奴), a nomadic power of the Eastern Eurasian Steppe, and are noted in the context of increasing trade along the Silk Road during the Han Dynasty (c. 202 BC–AD 220) (Wang Reference Wang2013). Although donkey remains dating to that period have not been documented, several skeletons are reported to have been present in the Mausoleum of Emperor Hanzhao (漢昭帝; 94–74 BC; Yuan Reference Yuan2007).

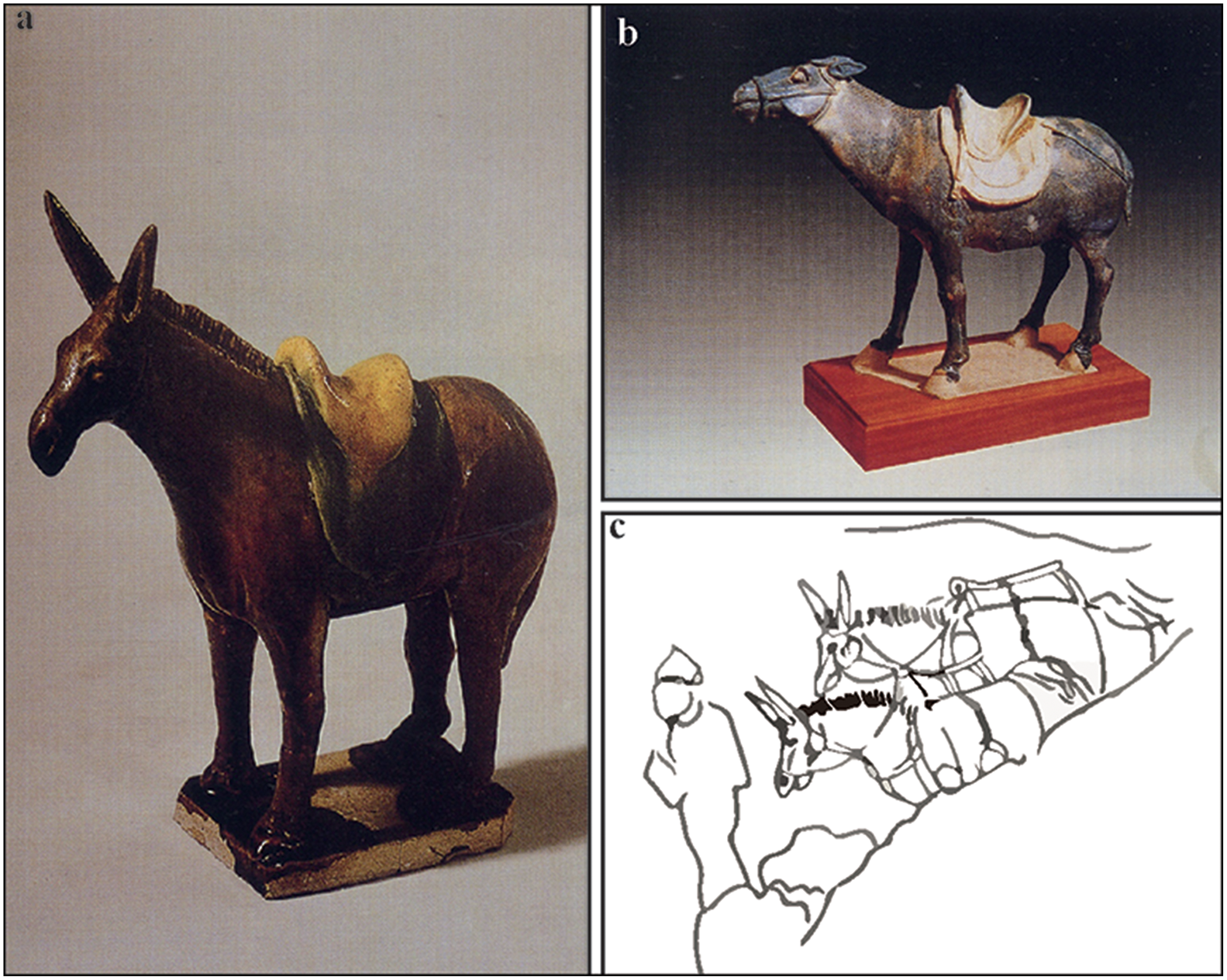

Xi'an, ancient Chang'an, was the capital and economic and administrative centre of the Tang Dynasty. Chang'an was a large cosmopolitan city and, as the starting point of the Silk Road, linked to Central Asia. Historical texts indicate that donkeys were important pack animals on the Silk Route (Figure 1c; Zhu Reference Zhu1995). More locally, they were widely used as household pack animals, and in commercial, military and official transport (Chen Reference Chen2007). A Tang Dynasty imperial edict states that, as with horses and cattle, donkeys were considered valuable resources and were not generally eaten or killed (Chen Reference Chen2007). Two governmental departments, responsible for animal husbandry countrywide and national transportation, regulated donkey management (Chen Reference Chen2007; Wang Reference Wang2016). While ordinary people also rode donkeys, it was rare for those of higher social class to ride them for transport (Chen Reference Chen2007). To date, only two tri-coloured, glazed ceramic donkey figurines with saddles have been discovered in Tang tombs (Figure 1a & b; Hu & Han Reference Hu and Han2001: 110). Historical texts in Jiutangshu (舊唐書) and Xintangshu (新唐書), however, indicate that the royal or noble classes sometimes rode donkeys for the sport of donkey polo.

Figure 1. a–b) Donkey pottery figurines found in Xi'an; c) sketch of Tang Dynasty Dunhuang paintings (figure edited by T. Wang).

As a game traditionally played on horseback, polo is thought to have developed in Iran and spread during the era of the Parthian Empire c. 247 BC–AD 224 (Liu Reference Liu1985; Chehabi & Guttman Reference Chehabi and Guttmann2002). By the seventh century AD, polo was played on the Tibetan Plateau and in central China (Liu Reference Liu1985; Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Xia2009). Considered a prestigious sport, and originally important for training cavalry, polo was played on horseback by the military and the Tang court in Xi'an, and was esteemed by many Tang emperors (Liu Reference Liu1985; Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Xia2009). The game, however, was dangerous and occasionally fatal, as the death of Emperor Muzong attests (唐穆宗) (reigned 821–824) (Liu Reference Liu1985). Donkey polo (Lvju (驢鞠) in Chinese), which used smaller, steadier donkeys rather than horses, became an alternative favourite participation sport for elite women and older individuals, as well as for the less affluent (Liu Reference Liu1985; Han et al. Reference Han, Liu and Wang2001; Chen Reference Chen2007; Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Xia2009; Meng Reference Meng2012). Although Lvju is mentioned in the historical literature, it has never been documented archaeologically.

Donkey skeletons excavated in the ninth-century AD tomb of an elite woman, the lady Cui Shi (崔氏) in Xi'an (Figure 2), provide the opportunity to examine the role of donkeys in ancient China. Here, we report the results of comprehensive investigations of these equid skeletons, including biometric and biomechanical analyses, AMS radiocarbon dating and carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis. By integrating historical texts and archaeological data, our aim is to describe the morphological features of Tang donkeys, determine their economic importance and understand their roles in relation to Tang Dynasty noble women.

Figure 2. Locations of Xi'an and Dunhuang (figure edited by T. Wang).

Archaeological context

Excavated in 2012, the tomb of Cui Shi is located at Qujiang, Yanta District, in Xi'an city (Xi'an Municipal Institute of Cultural Heritage Conservation and Archaeology 2018; Figure 2). The tomb, constructed of brick, with a vertical tomb entrance, a corridor and a single burial chamber, had been heavily looted. Its floor was paved with bricks and the walls decorated with paintings of male and female servants and musicians. Many grave goods were recovered, including a lead stirrup and a stone epitaph (Figure 3a–b), which states that the tomb belonged to Cui Shi, the wife of Bao Gao (高寶), the governor of the Jingyuan (涇源) and Zhenghai (鎮海) areas during the late Tang Dynasty. She died on 6 October AD 878, aged 59, and was buried on 15 August 879. Numerous animal bones were present in the corridor and on the coffin (Figure 3c–d).

Figure 3. Artefacts from Cui Shi's tomb: a) a stirrup; b) rubbing of stone epitaph; c–d) animal bones in the tomb (figure photographed by J. Yang and edited by T. Wang).

Methods

Osteological analyses

Songmei Hu and her zooarchaeological team have identified the animal skeletons in Cui Shi's tomb as donkeys (Equus asinus) and cattle (Bos cf. taurus). Dental analysis was undertaken to discriminate among equid species, such as donkeys and Asian wild asses (E. kiang and E. hemionus hemionus), and hybrid mules (male donkey, female horse) and hinnies (female donkey, male horse) (following Eisenmann Reference Eisenmann, Meadow and Uerpmann1986; Payne Reference Payne, Meadow and Uerpmann1991; Baxter Reference Baxter, Anderson and Boyle1998). Donkey ages were estimated based on tooth eruption and wear patterns (Hong & Yang Reference Hong and Yang1981). Premolars were examined for bit wear (Greenfield et al. Reference Greenfield, Shai, Greenfield, Arnold, Brown, Eliyahu and Maeir2018). Biometric measurements of three metatarsals from donkeys M1:D1, M1:D2 and M1:D3 were undertaken to estimate size (following von den Driesch Reference von den Driesch1976). Comparative biometric data from ancient and modern donkeys were collated from published sources (e.g. Eisenmann & Beckouche Reference Eisenmann, Beckouche, Meadow and Uerpmann1986; Clutton-Brock Reference Clutton-Brock, Oates, Oates and McDonald2001; Rossel et al. Reference Rossel, Marshall, Peters, Pilgram, Adams and O'Connor2008; Greenfeld et al. Reference Greenfield, Shai and Maeir2012; Bar-Oz et al. Reference Bar-Oz, Nahshoni, Motro and Oren2013; and Marshall's unpublished data).

AMS radiocarbon dating

Two bone samples, one from the M1:D2 donkey described here, and one from a cow, were submitted for dating by the Center for AMS radiocarbon dating at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Stable isotope analysis

The right and left metatarsals of specimens M1:D1 and M1:D2 were sampled for carbon and nitrogen (δ13C and δ15N) stable isotope analyses. The extraction of bone collagen and isotopic measurements followed the protocol reported by Xia et al. (Reference Xia, Zhang, Yu, Zhang, Wang, Hu and Fuller2018). Based on the criteria to identify the minimum collagen preservation (i.e. 41 per cent C content, 15 per cent N content, and a 2.9–3.6 C:N ratio; DeNiro Reference DeNiro1985; Ambrose Reference Ambrose1990), the collagen of two samples was considered to have retained their in vivo isotopic signatures.

Biomechanical analysis of donkey humerus using micro-CT scanning

To evaluate the biomechanical properties of donkey bones in relation to the animals’ roles in human society, we used microtomography (a micro-CT scanner 450ICT) to scan three intact donkey humeri: the left and right humeri from M1:D1 and the right humerus from M1:D2. The scanning protocol and reconstruction of the mid point of maximum length along the longitudinal axis of the humerus shaft followed Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Wallace, Jashashvili, Musiba and Liu2017), as the mid-shaft diaphysis of the long bones bears the greatest biomechanical stress (Biewener & Taylor Reference Biewener and Taylor1986). We therefore aligned each bone in its anatomical position and scanned the cross-sections at the mid point along the longitudinal axis of the humerus (Shackelford et al. Reference Shackelford, Marshall and Peters2013; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Wallace, Jashashvili, Musiba and Liu2017).

As the principal moments of areas (PMAs; Imax/Imin) ratio has previously provided a good estimate of cross-sectional shape and limb-loading history (Shackelford et al. Reference Shackelford, Marshall and Peters2013), we selected this index for comparison of African wild asses and the domestic donkeys from Cui Shi's tomb. We hypothesised that, if these donkeys were used for polo (see Williams et al. Reference Williams, Tan, Usherwood and Wilson2009), shaft geometry would more closely resemble that of wild asses, with locomotion that would be characterised by acceleration, deceleration and turns, rather than the steadier, slower gait of pack donkeys.

Results

Species identification and age estimation

We identified a minimum number (MNI) of three donkeys and four cattle (Bos cf. taurus) based on skeletal element, number and size. Here, we focus only on the donkeys.

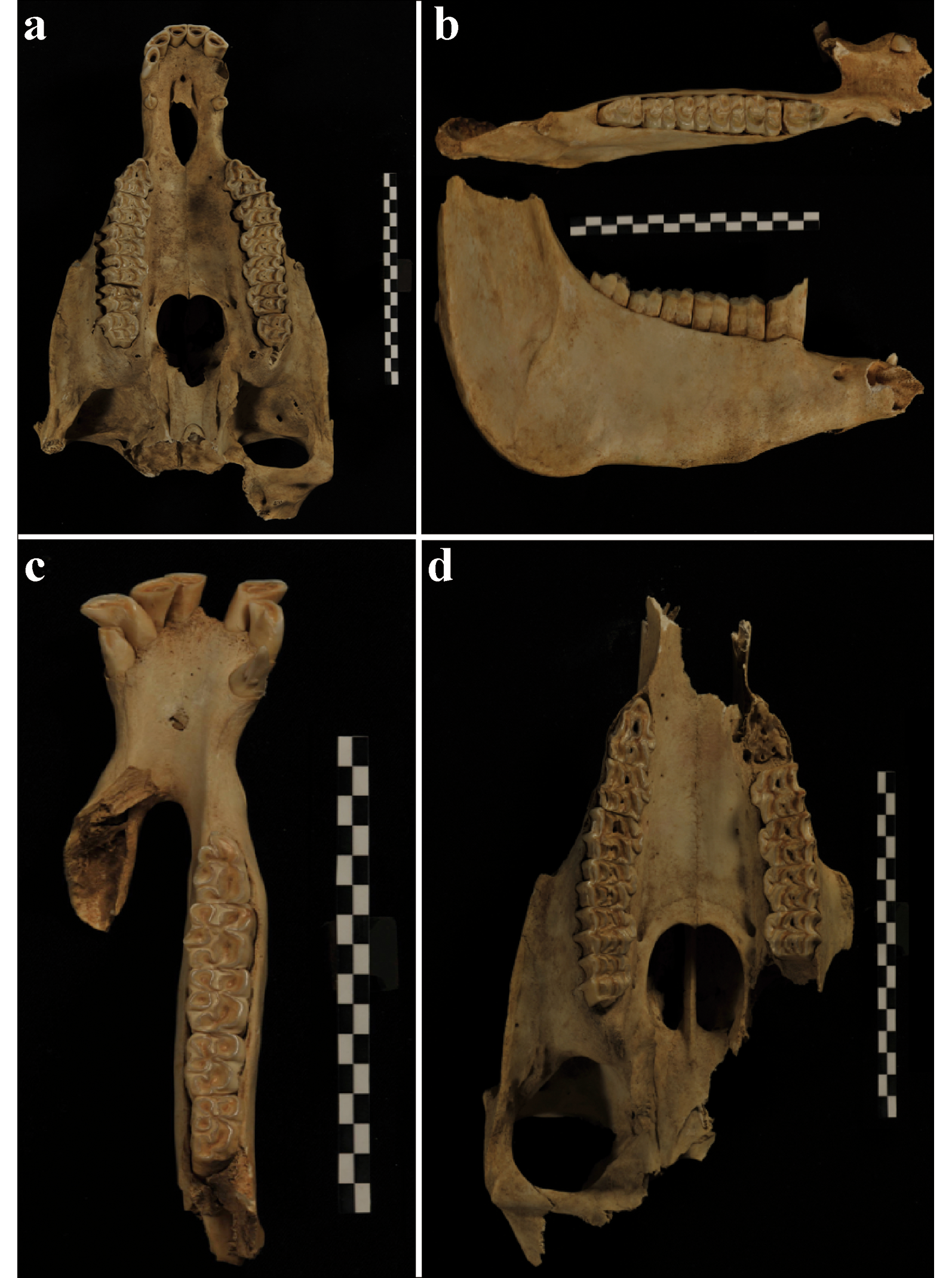

The dental characteristics of the two partial equid crania and mandibles from M1:D1 and M1:D2 correspond to those of donkeys (Figure 4), with maxillary teeth distinguished by ridges and folds characteristic of donkeys (i.e. short protocone, lack of plicaballin, straight ectoloph) and mandibular teeth with a shallow V-shaped groove (Eisenmann Reference Eisenmann, Meadow and Uerpmann1986; Payne Reference Payne, Meadow and Uerpmann1991; Baxter Reference Baxter, Anderson and Boyle1998). This is consistent with the results of mitochondrial DNA analysis of these two mandibles, which confirmed that they are not mules (Han et al. Reference Han2014). Dental morphology also confirms that these animals are not hinnies.

Figure 4. Crania and mandibles showing dental characteristics: a) maxilla of donkey M1:D1, occlusal view; b) mandible of donkey M1:D1, occlusal and lingual views; c) mandibular dentition of donkey M1:D2, occlusal view; d) maxilla of donkey (M1:D2), occlusal view (photographs by S. Hu; figure edited by T. Wang).

Although the lower incisors from donkey M1:D1 are not present, the wear face and the tooth pit (Hong & Yang Reference Hong and Yang1981) of the upper first incisor are round and oval in shape, respectively (Figure 4). This, along with slight wear to the right upper canine, suggests that the individual was 6–7 years old at death and most probably male. This animal also exhibits abnormal wear on its right lower and upper second premolar (Figure 5). This pattern is not related to bit wear, for which there is no evidence. As in wild and unbitted equids, the mesial-occlusal surfaces of the lower second premolars have flat and squared junctures without the bevelled enamel characteristic of bit wear (Greenfield et al. Reference Greenfield, Shai, Greenfield, Arnold, Brown, Eliyahu and Maeir2018). The left mandible of donkey M1:D2 contains incisors I1–I3 and a canine (C); the right mandible has a complete dentition, with the exception of the third molar (Figure 4). The worn occlusal face of the lower incisors suggests that this individual was approximately nine years old.

Figure 5. Cranium and mandible of donkey M1:D1 showing premolar wear (figure photographed by S. Hu and edited by T. Wang).

Biometric data

The metatarsals of donkeys M1:D1, M1:D2 and M1:D3 (Figure 6) are smaller than those from Middle Bronze Age (1700–1550 BC) donkeys at Tel Haror (Israel) (Bar-Oz et al. Reference Bar-Oz, Nahshoni, Motro and Oren2013), but similar in size to smaller Early Bronze Age (third millennium BC) examples from Tell Brak (Syria) (Table 1; Clutton-Brock Reference Clutton-Brock, Oates, Oates and McDonald2001). When compared with modern donkeys (Table 2), they resemble the smaller pastoral group, within the range of Maasai donkeys, and are similar in height at the withers to the smallest breeds found in modern China (0.90–1.10m) (FAO 2018).

Figure 6. Anterior and posterior views of the left metatarsals of: a–b) donkey M1:D3; c–d) donkey M1:D1; e–f) donkey M1:D2 (figure photographed by S. Hu and edited by T. Wang).

Table 1. Biometric comparison of metatarsals of Tang donkeys from Cui Shi's tomb and South-west Asian Bronze Age donkeys.

1 Measurements (Ms.) follow von den Driesch (Reference von den Driesch1976): GL = greatest length; GLL = greatest lateral length; Ll = lateral length; BP = proximal breadth; DP = proximal depth; SD = mid-shaft breadth; CD = circumference diaphysis; SDD = smallest diaphyseal depth; BD = distal articular breadth; DD = distal depth. Numbers in parentheses denote Eisenmann (Reference Eisenmann, Meadow and Uerpmann1986) equivalents.

2 Tel Haror, Israel, Middle Bronze Age (1700–1550 BC) data from Bar-Oz et al. (Reference Bar-Oz, Nahshoni, Motro and Oren2013: Table S1); donkey 1 = young, donkey 2 = older.

3 Tell Brak, Syria, Early Bronze Age (third millennium BC) data from Clutton-Brock et al. (Reference Clutton-Brock, Oates, Oates and McDonald2001: 333); donkey 1 = aged female, donkey 2 = female 3–5 years old.

Table 2. Biometric comparison of metatarsals of Tang donkeys from Cui Shi's tomb and modern donkeys.

Measurements follow von den Driesch (Reference von den Driesch1976) (numbers in parentheses denote Eisenmann (Reference Eisenmann, Meadow and Uerpmann1986) equivalents): GL (E1) = greatest length; LL (E2) = lateral length; ~SD (E3) = smallest shaft breadth; BP = proximal breadth; DD (E12) = depth at distal end; DP (E6) = proximal depth; BD (E10) = distal supra articular breadth.

Dating of donkey and cattle bones

The AMS radiocarbon dating of two samples (donkey and cattle; Table 3), when calibrated with the IntCal09 curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2009), place these animals at AD 856–898 (at 44.3 per cent probability) and AD 807–882 (at 87.3 per cent probability), respectively. These dates coincide with the date (AD 878) given on the stone epitaph. The animals were therefore buried at the same time as the occupant of the tomb, although we cannot be certain that the donkeys were used by Cui Shi herself.

Table 3. Radiocarbon dating of animals in the tomb of Cui Shi (calibrated using Calib 7.0 and the IntCal09 curve; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2009).

Isotopic results

The δ15N values of the two equid specimens are similar and are typical of herbivore isotopic signatures (Table 4). Although the δ13C values are different, they indicate that both individuals consumed substantial quantities of C4 plants (e.g. millets).

Table 4. Carbon and nitrogen elemental and isotopic data from donkey bones from Cui Shi's tomb.

Biomechanical analysis of donkey humeri

Biomechanical analysis demonstrates that the PMAs ratio of the three mid-shaft humeri of donkeys M1:D1 and M1:D2 is significantly greater than that of modern domestic donkeys and African wild asses (Figure 7; Table 5). The mid-shaft cross-sections of the three humeri are more elliptical in shape (Figure 8) compared with the more circular diaphyses of domestic donkeys and African wild asses. These shape differences provide a good indicator of mechanical loading. The humeri from M1:D1 and M1:D2 exhibit much greater strength on the maximum axes, indicating that the shafts were subject to heavy and persistent mechanical loading in one direction. This resembles neither the free-ranging locomotion characteristic of African wild asses, nor the more constrained pace of pack donkeys. While pulling carts, circular threshing activities or tight turns in polo playing could possibly produce such a pattern, modern analogues are not currently available to help interpret this result.

Figure 7. Anterior and posterior views of the left (a–b) and right humeri (c–d) of donkey M1:D1 and anterior and posterior views of the right humerus (e–f) of donkey M1:D2 (figure photographed by S. Hu and edited by T. Wang).

Figure 8. Mid-shaft cross-sections of donkey humeri: a) left humerus of donkey M1:D1; b) right humerus of donkey M1:D1; c) right humerus of donkey M1:D2 (figure produced by P. Wei).

Table 5. Mid-shaft cross-sectional properties (Imax/Imin) of donkey humeri.

a Mean value of the sample (Shackelford et al. Reference Shackelford, Marshall and Peters2013).

Discussion

The inclusion of donkey bones in an elite late Tang Dynasty tomb is unprecedented. Animal bones are rare in late Tang Dynasty tombs in general (Zheng Reference Zheng2017), and donkeys are usually associated with low social status. Our analyses of donkey morphology and management, alongside information on the importance of polo to Cui Shi's family (see below), provide the first archaeological evidence for the significance of donkeys to Tang Dynasty elite women.

Donkey morphology and management

Our analyses confirm the identification of the equids in Cui Shi's tomb as donkeys, and reveal that they were small animals, had unusual locomotion patterns and were well fed, with access to domestic grains.

Given the historical records concerning the role of the Tang government in overseeing donkey management and breeding for official transport, we expected that large donkeys—useful for transport as well as mule breeding—would have been common. The three donkeys from Cui Shi's tomb, however, are notably small, falling within the range of present-day Maasai donkeys in Africa (Table 2) and the smallest modern donkey breeds in China (FAO 2018). As these are the first ancient donkeys studied from an East Asian context, there are no comparative biometric data from periods before the Tang Dynasty.

The donkeys’ small stature may suggest that they were selected for purposes other than the transportation of goods, a hypothesis also supported by the presence of a stirrup in the tomb (Figure 3a) and our biomechanical analysis of the donkeys’ humeri. Slow, steady gaits typical of pack animals produce shaft morphologies that differ from those of animals that accelerate, decelerate and make sharp turns, as is characteristic of wild animals (Shackelford et al. Reference Shackelford, Marshall and Peters2013). The evidence for load pressure on the humerus indicates that the donkeys experienced much greater loading than seen in modern African wild asses or donkeys (see Shackelford et al. Reference Shackelford, Marshall and Peters2013). While there are no recently published studies for comparison, the discrepancy could be the result of differences in biomechanical measurement methodology (i.e. micro-CT vs X-ray). Our findings suggest, however, that the donkeys interred in the tomb were used for tasks other than simple burden carrying. The changes in speed and trajectory associated with polo make this a distinct possibility, although traction with heavy turning (e.g. milling) is also a possibility. While we cannot currently differentiate between these scenarios, the presence of a stirrup in the tomb makes traction the less likely option, considering the life history of the tomb's occupant and the tomb's symbolism.

Our analysis of the carbon stable isotopes provides insights into donkey diet and management. The carbon isotope ratios of the two donkeys from the tomb (−15.6‰ and −11.2‰) strongly suggest that millets (C4 plants) or other crop by-products (C3 plants) contributed significantly to their diets. This concurs with the management regulations of the Tapusi (太樸寺) governmental department, which specified that fodder should come from rice, beans and millets (Chen Reference Chen2007). The presence of donkeys in a mortuary setting and the high social status of the occupant of the tomb suggest that these animals were managed according to state regulations.

Polo and Cui Shi's family

During the Tang Dynasty, polo was a favourite pastime for the royal and noble families as well as the royal court (Liu Reference Liu1985; Chehabi & Guttman Reference Chehabi and Guttmann2002), to such an extent that the desire to play polo in the afterlife is expressed in Early Tang murals, such as those in the tombs of Prince Li Xian and Prince Jiemin (Eckfield Reference Eckfield2005). The text in Zizhitongjian (資治通鑒) reports that Emperor Xizong (唐僖宗) (reigned 874–888), who ruled during Cui Shi's life in the late Tang period, was obsessed with polo. For example, he used a game of polo to select which of four generals should command the key garrison in Xi'an, and was known for commenting that, if polo was a civil service examination topic, he would excel (Liu Reference Liu1985). According to the Xintangshu (新唐書), Cui Shi's husband, Bao Gao, was an excellent polo player. Esteemed by Emperor Xizong, Bao Gao was promoted to the rank of general due to his polo-playing skills (Zheng Reference Zheng2018). Polo was dangerous, especially during late Tang times (Liu Reference Liu1985): the Xintangshu records that Bao Gao lost an eye playing the game. Despite the risk, women of the Tang court were famous for enjoying polo, and were often portrayed playing it on horseback (Chehabi & Guttman Reference Chehabi and Guttmann2002). Many women, however, rode donkeys in the game of Lvju (Liu Reference Liu1985). Although gaited riding donkeys have been prized throughout history (Alkhateeb-Shehada Reference Alkhateeb-Shehada2008; Navas González et al. Reference Navas González, Vidal, Jurado, McLean, Inostroza and Bermejo2018), temperament is the most often cited reason for a rider choosing a donkey over a horse. The legacy of wild ass sociality and the territorial nature of males in particular can be seen in donkey behaviour; unlike herd-based horses, donkeys are more disposed to assess danger rather than to flee (Marshall & Asa Reference Marshall and Asa2013; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2018). Their owners often describe them as thoughtful and less subject than horses to panic in strange or frightening situations (The Donkey Sanctuary n.d.).

Cui Shi's husband and his family were of high social rank. In accordance with elite Tang mortuary customs, animals, such as the donkeys found in Cui Shi's tomb, were sometimes sacrificed at the time of burial, so that they could accompany the human spirit into the afterlife. Our site represents the first evidence of Tang donkey sacrifice. Furthermore, as the presence of such a relatively low-status transport animal in a high-status woman's tomb would be unprecedented, it is likely that there was a specific reason for the donkeys’ presence in the tomb: their use in the prestigious game of polo.

Donkeys were neither eaten nor used for everyday transport by elite women in the Tang Dynasty. Given Cui Shi's access to and familiarity with polo through her husband, and as a member of the Tang elite, it is likely that she played polo. It is possible that, for safety reasons, she selected Lvju as a popular game specifically for women and played by the royal and noble classes (Han et al. Reference Han, Liu and Wang2001; Chen Reference Chen2007; Meng Reference Meng2012; Xia Reference Xia2015; Lu Reference Lu2016). We estimate the age of two of her donkeys (M1:D1 and M1:D2) to be over six years old—an age suitable for the demands of Lvju.

Although it is not possible to demonstrate conclusively that the donkeys in Cui Shi's tomb were used to play polo, a variety of data combine to support this interpretation. Evidence includes elite cultural customs and Tang mortuary tradition, personal family history, donkey size and age, and the presence of riding equipment in the tomb. Thus, we argue that the donkeys in Cui Shi's tomb reflect her love of donkey polo, and were sacrificed to provide the deceased with the means to play Lvju in the afterlife.

Conclusions

This study has used multiple analytical approaches to identify and interpret the donkey skeletons found in an elite woman's tomb of the late Tang period. While historical records and images of the Tang period demonstrate that donkeys were used in trade and transport, accounts of the Imperial Court emphasise that donkey polo (Lvju) was very popular with noble women in the Tang Court in Xi'an. The association of donkeys with the tomb of an elite woman is, however, unprecedented. Her family's special relationship with polo and the popularity of donkey polo suggest that, following Tang mortuary tradition, the donkeys were sacrificed to reflect Cui Shi's desire to play Lvju in the afterlife.

Dating to the ninth century AD, the donkeys from Cui Shi's tomb are the earliest so far documented in East Asia, providing the first archaeological evidence for the donkeys’ value among elite women in ancient China. From a broader perspective, the donkeys’ transition from pack animals to high-status polo mounts in ancient China extends our understanding of the complex role of donkeys in human history.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Tao Deng at the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for help and suggestions, and to Tingting Wang at Sun Yat-sen University for producing the figures. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (41773008, 41373018), Major Project of National Social Sciences (18ZDA218) and National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB953803).