Introduction

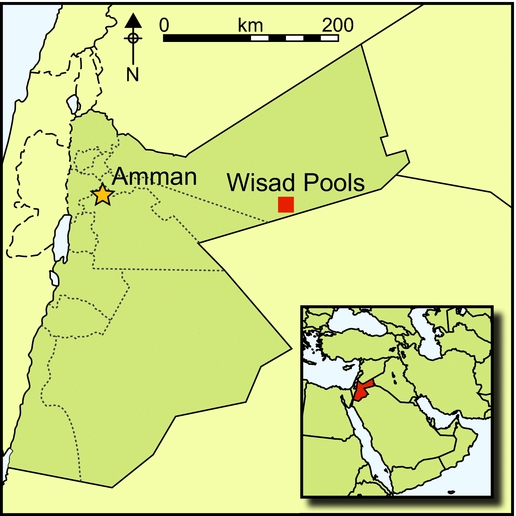

The Black Desert of Jordan is part of a huge plain of flood basalts (harra in Arabic; plural harrat) that covers around 40000km2, stretching from southern Syria into northern Saudi Arabia (Figure 1). The basalt, which has fractured over millions of years, covers a limestone formation in which flint of varying quality occurs. Basalt blocks and boulders cover the ground, making travel across the harra very difficult. Little can be discerned across the countryside except for occasional cairns that rise above the near horizon.

Figure 1. Location of the Wisad region in Jordan's eastern badia.

Soon after the end of the First World War, British pilots began flying an airmail route from Cairo to Baghdad, a good portion of which transected this blasted ‘land ofconjecture’ as one pilot mapmaker facetiously called it (Hill Reference Hill1925: map III). Percy Maitland was the first pilot to take aerial photographs across the route, and what he published was astonishing in terms of the richness of architectural elements and geometric features, which he called the ‘works of the old men’, a phrase used by Bedouin informants (Maitland Reference Maitland1927; cf. Rees Reference Rees1929).

Among the configurations of basalt boulders and slabs visible from the air reported as ‘works of the old men’ in Jordan's Black Desert were four major structure types: ‘kites’, ‘pendants’ (or ‘tailed tower tombs’), ‘meandering walls’ and ‘wheels’ (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2011). With walls that emerge from the surface less than half a metre high, most of the ‘old works’ are difficult to detect from the ground. Kites are huge constructions that in plan resemblethe children's toys of that name (Rees Reference Rees1929). Most are easily visible on Google Earth. The circular or polygonal enclosure at one end can have dimensions of more than 100 × 200m, with guiding walls (50–75cm high) that extend up to 7.5km or more in length leading to the enclosure (Kempe & al-Malabeh Reference Kempe and al-Malabeh2013: 134). Based on the 557 kites they could identify on Google Earth, Kempe and al-Malabeh (Reference Kempe and al-Malabeh2013: 134) have calculated that the labour involved in constructing all of the kites in Jordan would have been equivalent to half the work of building the Cheops Pyramid in Egypt, although Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Banks and Houghton2014: tab. 1, which lists between 1387 and 1500 kites for Jordan) suggest by inference that the labour input would have been triple this amount.

Table 1. Dates from OSL samples from Wisad Wheel 60 and Wisad Wheel 2.

There has been disagreement as to the function of kites, with one faction strongly supporting a pastoral association (e.g. Kirkbride Reference Kirkbride1946; Échallier & Braemer Reference Échallier and Braemer1995), and another supporting a purpose for funnelling and trapping of desert fauna for slaughter (Zeder et al. Reference Zeder, Bar-Oz, Rufolo and Hole2013). Recent excavations of walled pits incorporated into kite-enclosure walls have shown they measured about 2m in diameter and reached depths of 1.7–2m in the Black Desert and in the Jafr Basin of southern Jordan (Abu-Azizeh & Tarawneh Reference Abu-Azizeh and Tarawneh2015: 108, fig. 19; Abu-Azizeh pers. comm.; cf. Barge et al. Reference Barge, Brochier, Regagnon, Chambrade and Crassard2015), strengthening the argument for kites as hunting devices and greatly increasing the probable amounts of labour involved in kite construction.

So far, absolute dates for kite construction are rare (fifth–third millennium BC in southern Israel; Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Bar-Oz, Avner, Boaretto and Malkinson2010), although more dates might be available soon (Abu-Azizeh pers. comm.). Betts has noted that a Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (c. 7500–7000 cal BC) structure at Dhuweila in the western harra incorporated the guiding wall of a kite in its architecture (Helms & Betts Reference Helms and Betts1987; Betts et al. Reference Betts, Colledge, Martin, McCartney, Wright and Yagodin1998), although this is not accepted by some scholars, who argue for much later ages, e.g. Chalcolithic to Iron Age (Échallier & Braemer Reference Échallier and Braemer1995: 55), or Early Bronze Age at the earliest (Zeder et al. Reference Zeder, Bar-Oz, Rufolo and Hole2013: 115). Recent identification of stratigraphic superposition of Late Neolithic hunting camps overlying kites in the western harra adds new support for Betts's claim (Akkermans et al. Reference Akkermans, Huigens and Brüning2014). Extending across the Near East, Arabia, Caucasus and Central Asia (Barge et al. Reference Barge, Brochier, Regagnon, Chambrade and Crassard2015), it is probable that the construction of kites occurred over a long period of time, perhaps over several thousand years.

Pendants are tall burial cairns, about 3m in diameter at the base, sometimes reaching 3m in height and often accompanied by a series of stone-built chambers or simple piles of stone radiating out in a chain of variable numbers, perhaps as memorial cenotaphs (cf. Rowan et al. Reference Rowan, Rollefson and Kersel2011). Atop Maitland's Mesa, for example, there is a pendant/tower tomb with an attached ‘tail’ of more than 50 chambers (each about 2m long, 1m wide and 1m high) along the southern edge of the mesa, and at Wisad Pools there is a pendant with 44 chambers (Rollefson et al. Reference Rollefson, Wasse, Rowan, Rollefson and Finlayson2014b: 289). Investigation of pendants at both Maitland's Mesa and Wisad Pools have shown them to be empty of any evidence of cultural inclusions (Rollefson et al. Reference Rollefson, Rowan, Perry and Abu-Azizeh2012: 41; Rowan et al. Reference Rowan, Rollefson, Wasse, Abu-Azizeh, Hill and Kersel2015a: 180). Other tower tombs lack attendant chambers and can be assumed to be ‘pendants manqués’. Notably, pendants usually occur on hilltops or other features where they are easily visible, perhaps as symbolic announcements of a prominent person's final resting place. It has not yet been possible to obtain any dates from pendants, and it is possible that they were constructed over a very long time during the late prehistoric period.

Meandering walls are low, zig-zagging barriers that criss-cross the ground for several kilometres; their use remains conjectural, but Betts (Reference Betts1983) and Kempe and al-Malabeh (Reference Kempe, al-Malabeh and Middleton2010) have suggested they may be the original precursors to kites. At Wisad Pools, Google Earth images indicate that a meandering wall extends around 7km in length SSW–NNE (possibly interrupted at some points), crossing the central portion of the vast complex of Wisad's various structures (Rollefson et al. Reference Rollefson, Wasse, Rowan, Rollefson and Finlayson2014b). It is not possible at this time to provide a date for this (or any other) meandering wall, but its close proximity to residential structures might indicate that it is older than most of them, especially if the meandering wall was used in some hunting strategy. Three excavated buildings at Wisad Pools all date to 6500–6000 cal BC, or the earlier part of the Late Neolithic period; the meandering wall is possibly older. Meandering walls appear to be shallow, so obtaining OSL samples would be useful in resolving the chronographic problem.

Meandering walls also occur in the mesa area of Wadi al-Qattafi. Although there has been substantial erosion and covering deposition in the tributary west–east wadis leading into the major Wadi al-Qattafi, the wall appears to connect the bases of the mesas, perhaps in order to create barriers between them. A similar phenomenon was noted during a preliminary survey of the Umm Nukhayla mesas about 10km to the south-west of Maitland's Mesa. All of these inter-mesa walls are reminiscent of the low-lying walls (murettes) documented by Abu-Azizeh in his survey of the Thlaythuwat region of south-eastern Jordan; murettes also link topographic rises in the hyperarid landscape (Abu-Azizeh pers. comm. 2011; cf. Abu-Azizeh Reference Abu-Azizeh2010).

Finally, roughly circular arrangements of basalt blocks termed ‘jellyfish’ (Betts Reference Betts1982), ‘wheelhouses’ (Kempe & al-Malabeh Reference Kempe, al-Malabeh and Middleton2010, Reference Kempe and al-Malabeh2013) or, simply, ‘wheels’ (e.g. Kennedy Reference Kennedy2011; Akkermans et al. Reference Akkermans, Huigens and Brüning2014) make up the final category. According to Kennedy (Reference Kennedy2012: 79), more than 1000 wheels have been identified within the basalt fields of eastern Jordan and Syria, but so far there have been no secure means to date the construction of these enigmatic features. The sizes, geometric regularity, internal and external features, and integrated clustering of two or more wheels reveals an expansive diversity that may represent temporal development to some degree, but the persistence of some simpler forms over great periods of time (see below) suggests that variation in wheel construction may also be related to differences in how they were used. Results of recent OSL assays of samples from two wheels from the Wisad region of the Black Desert indicate that one was constructed during the Late Neolithic period and that the other was built at the Late Chalcolithic–Early Bronze Age transition.

The Wisad wheels

The Wisad region (Figure 1) contains all of the structures characteristic of the Black Desert, including kites; tower tombs, burial cairns and other ritual structures; dwellings; animal pens; meandering walls; path enclosures; and wheels (cf. Rollefson et al. Reference Rollefson, Rowan and Wasse2011, Reference Rollefson, Rowan and Wasse2014b). One group of wheels is distributed across 1.75km over gentle, basalt-strewn slopes (Figure 2a), ending about 3.25km south to south-west from the centre of the large (around 10km2) archaeological settlement of Wisad Pools.

Figure 2. a) Schematic diagram of the relationship among the wheels and with the site of Wisad Pools; b) schematic view of Wisad Wheel 71; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale.

Wisad Wheel 71 (hereafter WW71) is the farthest south of the group (Figure 2b; wheel numbers follow the scheme developed by the Aerial Photography Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East (APAAME) project). It is roughly circular, approximately 50m in diameter, and subdivided by interior walls into four unequal sections (general descriptions and measurements are based on Google Earth images, as are the schematic sketches). Section 1, in the western part of the wheel, measures around 29m east–west and 33m north–south; inside this section is a circular cell, 5m in diameter, tucked against the inner face of the western wall of the wheel, and seven small cairns. Section 2, to the north-east, measures 36m north-west to south-east by 20m north-east to south-west; it contains four cairns. Section 3, in the south-eastern part of the wheel, is the smallest at 15m north-west to south-east by 20m north-east to south-west, and has three cairns. Section 4, in the south-western part of the wheel, is 29m north–south by 29m east–west; it contains five cairns.

The centre of WW70 (Figure 3a) lies 232m north-east of the centre of WW1. The inner surface of this wheel is incompletely segmented into three sections: the western section is about 37m north to north-west by 25m west-south-west to east-north-east and includes six cairns, the eastern section is 38m north-east to south-west by 18m north-west to south-east and encloses eight cairns; and the northern section is 30m north-west to south-east by 15m north-east to south-west, with only four cairns. A 3.5m-diameter cell is located on the southern rim and another, 3.2m in diameter, is located on the exterior of the eastern perimeter.

Figure 3. a) Schematic view of Wisad Wheel 70; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale; b) schematic view of Wisad Wheel 61; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale. The oval structure at the upper right and the subrectangular structure at the bottom are probably much later features. The rock alignment entering the wheel from the upper right and continuing across the wheel is part of a meandering wall.

WW61 is 365m east of WW70. It is an irregular, bag-shaped enclosure with measurements of 72m north–south by 63m east–west. It has a number of interior walls that are difficult to deconstruct; the wheel appears to be a palimpsest of different construction phases, with some of the more recent structures obliterating earlier ones (Figure 3b). To the east of the wheel is a segment of a meandering wall (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2011: fig. 11) that extends south 3.22km from the southern edge of the Wisad Pools site in a direct, straight line from the northern origin to the southern terminus. The total length, including each segment of the meandering wall, is greater than 7.3km, taking into account the frequent major alterations. Considering calculations by Kempe and al-Malabeh (Reference Kempe, al-Malabeh and Middleton2010: 212–13; Reference Kempe and al-Malabeh2013: 226), this is an astounding amount of labour over only a few kilometres. The oval structure in the upper left of Figure 3b and the sub-rectangular building at the bottom centre are probably recent historical constructions.

Approximately 435m north-east of WW70 is WW60 (Figures 4 & 5). In Figure 4, a more northerly trending, saw-toothed offshoot of the meandering wall mentioned above continues its zig-zagging trajectory northwards for more than 4km (total of wall segments) until it disappears; there is no way to determine at this point any possible relationship of Wheels 60 and 2 with the meandering wall. WW60 is a slightly deflated circular shape about 50m across with three or four interior sections, three of which contain cairns. The north-western section of the wall of the wheel has been interrupted by later robbing of the stones for several oval structures, which are clearly more recent in date. To the north-west is the remnant of a cleared ‘pathway’ (cf. Kempe & al-Malabeh Reference Kempe, al-Malabeh and Middleton2010: 209–10, fig. 10), demonstrating a stratigraphic relationship, the pathway being younger than the wheel.

Figure 4. View towards the east of Wisad Wheel 60 (right) and Wheel 2 (left). In the distance, near the top of the photograph, is a complex meandering wall that traverses 3.22km southwards in massive zig-zags from the southern edge of the Wisad Pools site; photograph modified from © Robert Bewley, APAAME_2009_1004_RHB-0108, by permission.

Figure 5. View towards the north-west of Wisad Wheel 60; note the circular cleared pathway adjacent to the north-west; photograph modified from © Robert Bewley, APAAME_20091004_RHB-0105, by permission.

WW2 is 150m north-north-east of WW4 (centre to centre) and is elliptical in plan (Figure 6). Internal walls divide the interior into five sections, only two of which contain cairns. The sediment inside the wheel is much brighter than the surface of WW60, perhaps indicating more recent disturbance of the surface.

Figure 6. Image of Wisad Wheel 2; north is at the top of the image; photograph modified from © Robert Bewley, APAAME_20091004_RHB-0108, by permission.

About 650m north of WW2 is the southernmost of two more wheels (cf. Figure 7). WW58 has no interior subdivisions (Figure 8a), and for this reason perhaps it should not be called a ‘wheel’ but simply an irregular enclosure. The enclosure is sub-rectangular, measuring about 38m north–south by 28m east–west. There are a minimum of 13 cairns inside the wall. WW57, 310m farther to the north-east, is a sub-equilateral triangle measuring 38m north–south by 40m east–west, with four areas delineated by walls; the sections each contain between one and eight cairns (Figure 8b). An interesting aspect of WW57 is that it is nestled within one of the angles (and shares a wall or two) with the same meandering wall segment seen in Figure 7. This demonstrates a stratigraphic relationship, with WW57 constructed after the meandering wall.

Figure 7. View towards the south-west of Wisad Wheel 58 (top, left centre) and Wisad Wheel 57 (right centre); the same meandering wall as in Figure 4 is in the centre of the image; photograph modified from © Karen Henderson, APAAME_20091004_KRH-0067, by permission.

Figure 8. a) Schematic view of Wisad Wheel 58; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale; b) schematic view of Wisad Wheel 57; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale; note that WW57 is nestled in one of the angles of the meandering wall.

WW75 lies just over 600m west-north-west of WW60. The wheel, which has been subdivided into three unequal sections, is 30m in diameter and contains 20 cairns (Figure 9a). As with WW58, WW62 might not fit the ‘wheel’ category (Figure 9b). It could be a pastoral enclosure with two oval huts in the interior with dimensions of 9 × 13m for the western structure and 10 × 11m for the northern one; another rectangular structure measuring 9 × 13m is located on the exterior of the eastern wall of the enclosure. There are two possible cairns, but these might have been created when the enclosure was abandoned.

Figure 9. a) Schematic view of Wisad Wheel 75; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale; b) schematic view of Wisad Wheel 62; the black dots are cairns, and are not shown to scale.

Chronometric dating

Soil samples for OSL dating taken by present author C.A., and assayed by the Heidelberg Luminescence Dating Laboratory, Institute of Geography, University of Heidelberg, Germany, have provided the first absolute dates for this class of the ‘works of the old men’. Radiocarbon dates have been obtained for Late Neolithic dwellings excavated at Maitland's Mesa (M-4) in the Wadi al-Qattafi (Wasse et al. Reference Wasse, Rowan and Rollefson2012) and Wisad Pools (Rollefson et al. Reference Rollefson, Rowan and Wasse2014a; Rowan et al. Reference Rowan, Rollefson, Wasse, Abu-Azizeh, Hill and Kersel2015a & b). Three samples were taken from the perimeter wall of WW60 and three from the outer wall of WW2 (a fourth sample was taken from the base of a cairn inside WW2).

OSL samples were collected at night to avoid the risk of exposing them to daylight. Suitable slabs (i.e. with no evidence of any disturbance) at the base of the walls, which were only one or two courses high, were spotted during the day and marked out. The slabs were overturned at night and material was collected from beneath the basaltic slab, specifically from aeolian sand veneer, a few centimetres thick, interposed between the basaltic slab and the underlying alluvial basement. Prevalence of quartz (macroscopically recognised) dictated a quartz-based OSL-dating approach. The material was submitted to standard chemical preparation procedures (cf. Athanassas Reference Athanassas2011; Athanassas et al. Reference Athanassas, Bassiakos, Wagner and Timpson2012). Pure quartz aliquots were measured using the single aliquot regenerated (SAR) protocol by Murray and Wintle (Reference Murray and Wintle2000) in order to estimate the palaeodose. Raw material was analysed by ICP-MS (ACME Labs, Vancouver, Canada) and the elemental concentrations of uranium, thorium and potassium were determined in order to model the dose rate. Palaeodoses were combined with the dose-rate figures to generate OSL ages for the structures. A detailed description of the laboratory procedures is illustrated in Athanassas et al. (Reference Athanassas, Rollefson, Kadereit, Kennedy, Theodorakopoulu, Rowan and Wasse2015). The resulting OSL ages and their corresponding uncertainties (standard error) are shown in Table 1.

The range of dates for WW60 is broad (2590 years), but overall it points to a later Neolithic period rather than anything more recent. This has important implications for the cleared pathway that appears to be truncated by the western wall of WW60. The range of potential dates for Wheel 2 is much tighter (1850 years) and clearly indicates a Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period for the construction (and possible reconstruction) of the feature. The much earlier date for the sample from under the cairn inside WW2 (WW24) is anomalous and should be considered to be a date for the cairn and not for the wheel. Note that the brighter colour of the interior of WW2 supports a later use of the area; whether or not the cairn was undisturbed during the later use is conjectural.

Discussion

Cultural turbulence in the agrarian regions of the southern Levant coincided with an intensified exploitation of the steppe and desert of the eastern part of the region (Rollefson et al. Reference Rollefson, Rowan and Wasse2014a; Rollefson in press). A new economic scheme developed in the eastern ‘badlands’: herder-hunters expanded their subsistence base successfully, and a sizeable and growing population emerged in what is today a Stygian landscape. There is reason to believe that the Late Neolithic countryside was less forbidding than that of today: excavations at Wisad Pools have uncovered a thick (0.35–0.4m) topsoil protected from erosion, which would have absorbed much of the seasonal rainfall; furthermore, charcoal from deciduous oak and tamarisk were recovered from two hearths in a building dated to c. 6500 cal BC (Rowan et al. Reference Rowan, Wasse, Rollefson, Kersel, Jones and Lorentzen2015b).

The ‘works of the old men’ also seem to have started during the earlier part of the Late Neolithic period, including the construction of kites and, based on the new OSL dates, also the wheels. The function of wheels has been a matter of debate for some time and resolving this question may take a great deal of additional research. Betts (Reference Betts1982: 184) was convinced that they were residential complexes protected by a low wall against winds and floodwater in the rainy season, and even protection against other human groups. A pastoral/residential setting is also seconded by Müller-Neuhof (pers. comm.), who thinks they may be fortified settlements with small garden plots to take advantage of opportunistic cultivation. Kennedy (Reference Kennedy2011: 3189; Reference Kennedy2012: 81), on the other hand, leans towards a ritual nature for the wheels in view of the frequent presence of cairns within their perimeters. This certainly seems plausible for the simple wheel forms at Wisad, and the presence of internal dividing walls might separate burial plots for families within a cooperative herding-hunting group. Notably, however, a pedestrian survey within and outside Wisad Wheels 2 and 60 in 2009 found no surface artefacts at all, which would be unlikely if they were residential compounds. But these differing views may be comparing apples and oranges: the contrast between the plans of the Wisad wheels and more complex examples (Figure 10) would argue against a single function applicable to all circular enclosures termed ‘wheels’, and suggests that different wheel subtypes probably served different purposes.

Figure 10. a) Google Earth view of a cluster of complex wheels approximately 9.5km south-west of Azraq Castle, © Google Earth; b) a cluster of complex wheels near North Azraq; photograph modified from © David Kennedy, APAAME_20020401_DLK_0156, by permission.

The relationship between kites and meandering walls has already been described, but what of the association between wheels and kites? Notably, wheels tend to occur in clusters (and not as random, independent features), and overall there tends to be a negative correlation with kites (Athanassas et al. Reference Athanassas, Rollefson, Kadereit, Kennedy, Theodorakopoulu, Rowan and Wasse2015), perhaps indicating that when one of these types of structures was in use, the other was not. Wheels are normally built away from mudpans (although not always), while kites are often in close proximity to these seasonal water resources. The occurrence of wheels that were built over possible ‘guiding walls’ or ‘traps’ of kites indicates that the hunting use of particular kites had been abandoned, and the presence of a wheel would not be detrimental.

The sets of dates from WW2 and WW60 indicate that wheels, as with kites, were features that were built over a long period of time, perhaps several thousand years. As has been attempted for kites, it may be possible to establish a typological seriation, although this would require many more dated samples from the wide variety of wheel forms (cf. Kennedy Reference Kennedy2011: fig. 8), as well as the definition of categorising criteria.

Such a seriation would be useful in cases where there is a clear stratigraphic relationship between wheels and other ‘works’. A cursory scan of Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Banks and Houghton2014), for example, shows a minimum of eight instances where wheels have been built inside or across kite ‘traps’ or ‘guiding walls’, and Kempe (pers. comm.) has shown at least one more example. WW57 is clearly a later construction, set in the angle of the adjacent meandering wall, and there are probably numerous other examples across the landscape. The dates from WW60 and WW2 begin the process of establishing a chronology of the ‘works’ in the Black Desert, and they are a first step in unravelling these enigmatic constructions that consumed so much effort by the people who built them: an effort that must have been worth the enormous labour it entailed.

Acknowledgements

OSL dating of wheels in Wadi Wisad was possible through the Mistrals-EnviMed programme for the period 2012–2014 under the acronym W.O.MEN (Works of the Old Men). We are thankful to Annette Kadereit and the Heidelberg Luminescence Dating Laboratory, University of Heidelberg, Germany, for hosting C.A. and the OSL dating. Fieldwork during the Eastern Badia Archaeological Project from 2009 to the present has been principally supported by the Whitman College Perry Scholarship fund, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and the deep pockets of the co-directors of the project. We owe a great debt for the continued success of the project to the cooperation of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, and especially to the American Center of Oriental Research in Amman. We are also indebted to the resources of the Aerial Photography Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East (APAAME) and the assistance of David Kennedy and his staff for their permission to use aerial photographs. We would further like to thank the anonymous reviewers for comments that greatly improved the quality of the text.