Introduction

Horseback riding and the use of chariots has been linked with dramatic changes to the form and scale of social organisation among prehistoric peoples, but the chronology of their adoption in East-Central Asia remains poorly understood. Towards the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1300–700 BC), ‘deer stone’ stelae, accompanied by kurgan-like khirigsuurs and ritual horse-sacrifice features, appear to be the archaeological signature of the first horse-riding nomadic pastoralists in the Eastern Steppe of Eurasia. Horse transport in this ‘Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex’ would imply important changes in mobility, social stratification and structure (Anthony et al. Reference Anthony, Telgin and Brown1991; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015: 212–15), and suggest an expanded role in regional patterns of social interaction during the late Bronze Age.

Where other forms of direct evidence are lacking, faunal pathology is a promising means of identifying equine transport through archaeological data (Dietz Reference Dietz and Levine2003). Dental morphology (Anthony & Brown Reference Anthony and Brown1998) and other osseous changes to the appendicular and axial skeleton have been linked to equestrian activity (Levine Reference Levine and Levine1999; Olsen Reference Olsen, Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006: 93; Bendrey Reference Bendrey2007). Archaeologists have, however, struggled to pinpoint pathological markers of riding or traction that pre-date the use of the metal bit and can be regularly assessed in archaeological samples. This paper develops expectations for anatomical changes to the equine skull that should accompany the use of domestic horses for transport. ‘Horse transport’ here refers to both mounted horseback riding and the use of horses as draught animals to pull chariots or other vehicles. Using precision measurement of 3D models, these predictions are tested using a sample of feral, captive and domestic horse remains from museum collections. Finally, the results are applied to an assemblage of horse skulls from archaeological sites belonging to the Deer Stone-Khirigsuur (DSK) Complex to evaluate the possibility of horse transport in the Eastern Steppe during the late Bronze Age.

The horse in ancient Mongolia and beyond

Between 1300 and 700 BC, and perhaps earlier, deer stones and khirigsuur monuments spread across north-west and central Mongolia. Khirigsuurs are large, fenced stone burial mounds. They regularly contain human remains (Littleton et al. Reference Littleton, Floyd, Frohlich, Dickson, Amgalantögs, Karstens and Pearlstein2012), although they may have also served non-mortuary functions (Wright Reference Wright2014). Deer stones may have been memorials for revered warriors. These standing stones typically depict stylised earrings, belts and representations of the face, along with belts, weapons, deer and other animal carvings (Honeychurch et al. Reference Honeychurch, Fitzhugh, Amartuvshin, Fitzhugh, Rossabi and Honeychurch2013: 80). Together, these monument types appear to be archaeological manifestations of a single cultural complex (Fitzhugh Reference Fitzhugh, Bemmann, Parzinger, Pohl and Tseveendorj2009a).

Many have suggested that DSK people were also pastoralists using the horse for transport (Allard et al. Reference Allard, Erdenebaatar, Olsen, Cavalla and Maggiore2007; Houle Reference Houle2010; Honeychurch et al. Reference Honeychurch, Fitzhugh, Amartuvshin, Fitzhugh, Rossabi and Honeychurch2013), a contention that is supported by developments elsewhere in Eurasia. From the late third and early second millennium BC, there was an expansion in the use of chariots across the continent, and by 1200 BC, cultures using the horse for transport had already spread eastwards out of Central Asia (Hanks Reference Hanks2010: 475–76). Iconographic depictions of horse riders, and bone cheekpieces from mortuary contexts, show that horse-control technology was present in the forested regions bordering northern Mongolia c. 1400–1000 BC, coeval with the early DSK period (Legrand Reference Legrand2006). Due to an absence of actual tack or riding artefacts in the DSK archaeological record, there remains some question as to how horses were used by DSK people (Honeychurch et al. Reference Honeychurch, Wright, Amartuvshin, Hanks and Linduff2009).

Horse sacrifice was the most important aspect of ceremonial activity at deer stones and khirigsuurs, and DSK sites have produced circumstantial evidence for horseback riding and chariotry. Small stone mounds around the perimeter of both monument types contain equine skulls, often accompanied by cervical vertebrae and hoof bones (Fitzhugh Reference Fitzhugh, Bemmann, Parzinger, Pohl and Tseveendorj2009a). Previous faunal analyses suggest that horses were culled and eaten by DSK people (Allard et al. Reference Allard, Erdenebaatar, Olsen, Cavalla and Maggiore2007; Houle Reference Houle2010: 126–29). Most compellingly, deer stone carvings show artefacts and other features that suggest the horse was used for transport. For example, the ‘belt’ of weapons and tools carved into many of these deer stones commonly includes a small horse representation, alongside weapons and other important equipment (Volkov Reference Volkov2002) (Figure 1, left). Deer stone carvings show bow-shaped objects, often found in Chinese chariot burials (Wu Reference Wu2013: 40), which might have been used as chariot rein hooks (Fitzhugh Reference Fitzhugh, Hanks and Linduff2009b; Fitzhugh & Bayarsaikhan Reference Fitzhugh, Bayarsaikhan and Sabloff2011: 178) (Figure 1, right). Although only one deer stone depicts a chariot (Volkov Reference Volkov2002), such vehicles are a regular feature of Mongolian rock art panels attributed to the late Bronze Age (Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015: 192–93). Given these considerations, it is possible that people of the DSK Complex were nomadic horse pastoralists (Honeychurch et al. Reference Honeychurch, Fitzhugh, Amartuvshin, Fitzhugh, Rossabi and Honeychurch2013).

Figure 1. Depictions of small horses alongside weapons such as daggers, bows and quivers (left–centre) on deer stones in Mongolia; also depicted are chariots (second from right) and chariot ‘rein hooks’ or ‘bow-shaped’ objects (far right) referenced in the text; modified from Volkov (Reference Volkov2002).

If DSK people did indeed use horses for riding or chariotry, they may have played an underappreciated role in the spread of the horse into other parts of East Asia. Centuries before the ‘Silk Road’ trade routes were formalised, the grasslands of the Steppe acted as an informal ‘Steppe Road’, facilitating cultural and economic exchange across the Eurasian continent (Christian Reference Christian2000). Domestic horses first reached China, along with chariots, during the late Shang Dynasty (1600–1050 BC), the earliest specimens dating to c. 1300–1200 BC (Yuan & Flad Reference Yuan, Flad and Mashkour2006; Kelekna Reference Kelekna2009), much later than elsewhere in Central Asia. The geographic source of these first animals is an open question (Yuan & Flad Reference Yuan, Flad and Mashkour2006: 258–59), but several lines of evidence implicate the steppe cultures of Mongolia. Along China's northern frontier, steppe artefacts in late Bronze Age burials, particularly those of elites, suggest an acceleration of Sino-Mongolian interaction (Shelach Reference Shelach2009: 128–29). Perhaps most interestingly, recent genetic research indicates a close phylogenetic link between ancient Chinese and modern Mongolian horses (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Tang, Han, Speller, Yang and Ma2009). Clarifying the role of the horse in DSK society is thus crucial to an understanding of East Asian social dynamics in the first and second millennia BC (Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015: 205–10).

Archaeozoological identification of riding and chariotry

Although human management of domestic horses dates to the Eneolithic, c. 3500 BC (Olsen Reference Olsen, Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006; Outram et al. Reference Outram, Stear, Bendrey, Olsen, Kasparov, Zaibert, Thorpe and Evershed2009), archaeologists disagree as to when domestic horses were first used for riding and human transport (e.g. Renfrew Reference Renfrew and Mithen1998; Anthony Reference Anthony2007), and how to identify the signature of such transport in the archaeological record (Levine Reference Levine and Levine1999). Diagnostic horse-control devices, such as metal bits, are rarely recovered in East Asia from before the first millennium BC (Mair Reference Mair and Levine2003: 170). Leather harnesses and other organic methods of control used by early equestrians are unlikely to have been preserved in most archaeological contexts (Olsen Reference Olsen, Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006). In the absence of texts or exceptional preservation, palaeopathology provides the most direct dataset for the evaluation of ancient horse transport (Dietz Reference Dietz and Levine2003).

Osteological techniques for identifying equestrianism in horse remains have been debated at length (e.g. Anthony & Brown Reference Anthony and Brown1998, Reference Anthony, Brown and Levine2003; Levine Reference Levine and Levine1999; Olsen Reference Olsen, Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006; Bendrey Reference Bendrey2007). The best-known zooarchaeological index of equestrianism is ‘bit wear’: localised bevelling of the anterior surface of the second premolar caused by grinding or chewing a bit. Experimental and comparative studies have suggested that bevels greater than 3mm in magnitude are evidence of equestrianism (Anthony & Brown Reference Anthony and Brown1998, Reference Anthony, Brown and Levine2003; Anthony et al. Reference Anthony, Brown, George, Olsen, Grant, Choyke and Bartosiewicz2006). In recent years, additional research has bolstered the argument that metal bits can produce archaeologically recognisable changes to the horse's second premolar, and cause new bone formation to the diastema of the lower jaw (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2007; Outram et al. Reference Outram, Stear, Bendrey, Olsen, Kasparov, Zaibert, Thorpe and Evershed2009). The impact of an organic bit or halter on premolar form is less clear. Although Anthony et al. (Reference Anthony, Brown, George, Olsen, Grant, Choyke and Bartosiewicz2006) argue that organic bits should also cause measurable bevelling, natural malocclusion can produce similar changes to the teeth of unworked horses (Levine Reference Levine and Levine1999; Olsen Reference Olsen, Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006: 100–101). More importantly, many forms of early horse control appear to have relied on pressure from a noseband, without the use of a bit at all (Littauer Reference Littauer1969). Difficulty in resolving the bit wear debate increases the importance of seeking alternative archaeozoological criteria for identifying horse transport.

The high frequency of equine crania in the archaeological record of many parts of Central Asia (Kuzmina Reference Kuzmina and Olsen2006) makes them particularly useful for the palaeopathological study of horse transport. Bendrey (Reference Bendrey2008) compared dozens of the skulls of horses used in riding and traction with those of E. przewalskii, which has never been domesticated. He identified that new bone formation at the site of nuchal ligament attachment (enthesopathy) occurred in high frequency among highly trained horses. Although similar features can be caused by other factors such as bacterial infection (e.g. Bendrey et al. Reference Bendrey, Cassidy, Bokovenko, Lepetz and Zaitseva2011), nuchal enthesopathy appears to be commonly caused by habitual activity such as horseback riding (Figure 2a). Despite this interesting pattern, Bendrey concluded that nuchal pathologies had limited utility for archaeological identification of horse use, as age dependency was a major concern (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008: 30). In addition, the E. przewalskii specimens showed a wide range of ossification levels, overlapping significantly with ‘worked’ horses used for traction (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. A) Nuchal ossification on a ridden horse (left); B) ossification scores for horses used for riding, traction or ‘driving’, as compared to ‘unworked’ E. przewalskii from European zoos (right); modified from Bendrey (Reference Bendrey2008).

The enthesopathic patterns of Przewalski's horses recorded by Bendrey (Reference Bendrey2008), however, may not accurately characterise those of predomesticate horses. Most or all of the E. przewalskii specimens in Bendrey's study came from zoo collections (Robin Bendrey, pers. comm.). Although these captive equids were never driven or ridden, the impact of zoo-related stress on the equine skeleton may mimic the effects of horseback riding. Horses respond to negative stimuli through avoidance or ‘panicked flight’ (Dietz Reference Dietz and Levine2003: 190). In captive animals, frustration of these natural avoidance mechanisms can induce neurological problems that cause nuchal stress (Hosey et al. Reference Hosey, Melfi and Pankhurst2013: 231). For example, up to 40% of wild equids in zoos develop ‘stereotypies’, where the animal engages in repetitive headshaking or similar behaviour (McDonnell Reference McDonnell1988). Other aspects of zoo life, such as chronic posture changes associated with feeding, may also increase neck strain over a horse's lifetime. As a result, undomesticated but captive equids are not an ideal comparative sample for the identification of cranial pathologies related to transport.

In addition to nuchal bone formation, osseous changes to the nasal portion of the skull are a new and potentially useful marker of ancient equine transport. Siberian people used pointed bone cheekpieces with tightened halters to control domestic reindeer during the Iron Age, and this strategy may have a more ancient history in the region (Fedorova Reference Fedorova2003a & Reference Fedorovab). Studded nosebands (Dietz Reference Dietz and Levine2003: 191) or burred cheekpieces were especially common methods of control in early horse headgear (Littauer Reference Littauer1969: 290–92). Such devices, which rely on stimulation of pressure-sensitive areas of the face, may have preceded the first use of the bit (Littauer Reference Littauer1969: 293), and were used in bridles for chariot horses on the northern steppes as early as the third millennium BC (Kuzmina Reference Kuzmina, Davis-Kimball, Murphy, Koryakova and Yablonsky2000). Pressure on the nose and cheek from nosebands or burred cheekpieces will irritate sensitive facial nerves, and nosebands may hinder the breathing of animals to the point of tissue damage (Littauer Reference Littauer1969: 293; Brownrigg Reference Brownrigg, Olsen, Grant, Choyke and Bartosiewicz2006: 170). Despite the great antiquity of these devices, most modern bridles still rely to some degree on pressure and stimulation of the nasal region of the horse for control (Dietz Reference Dietz and Levine2003: 191).

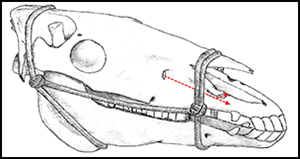

In the collections we examined, we discovered that many modern, ridden horse skulls have a pronounced groove along the dorso-medial border of the incisive bone (hereafter referred to as the ‘medial groove’) (Figure 3). This feature has been investigated in several veterinary studies (Perez & Martin Reference Perez and Martin2001; Vanderwegen & Simoens Reference Vanderwegen and Simoens2002). It is sometimes accompanied by a second, exterior groove, located rostrally along the bone's lateral margin (‘lateral groove’). Two related anatomical mechanisms are probably involved in such groove formation. Medial grooves are associated with activity of the lateralis nasi muscle and its accessory cartilage. It is hypothesised that sustained nostril dilation under conditions of chronic heavy breathing causes this muscle to hypertrophy, which in turn causes bone remodelling (Perez & Martin Reference Perez and Martin2001). The second, lateral groove may be developmentally related. This lateral grooving appears, however, to be related to an internal nasal branch of the infraorbital nerve (Perez & Martin Reference Perez and Martin2001). Preliminary study suggests that both kinds of remodelling are generally absent from wild equids such as zebra (Vanderwegen & Simoens Reference Vanderwegen and Simoens2002: 200).

Figure 3. Medial (A) and lateral (B) groove formation on the nasal process of the incisive bone of a ridden horse, US General John J. Pershing's warhorse Kidron (left), and the same region on a feral Chincoteague pony (right); specimens from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Insofar as the use of horses for transport causes increased respiration, grooves may track meaningful differences in human horse use. Domestic ridden animals should demonstrate extensive nasal remodelling caused by chronic exertion. Given that heavy breathing and nasal dilation are common stress responses in captive animals (Casey Reference Casey and Waran2002; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Iossa and Soulsbury2006; Hosey et al. Reference Hosey, Melfi and Pankhurst2013: 237), grooving should be more severe in zoo populations than in feral animals. In contrast, neither exertion nor other anthropogenic stressors should affect feral horses, where little grooving is expected. Finally, amongst animals where human transport drives osteological changes, high levels of nuchal ossification should also be matched by deeper nasal grooves.

Materials and methods

We studied a sample of 31 feral, ridden and zoo horse crania from museum collections at the National Museum of Mongolia, Khustai Nuruu National Park, the Museum of Southwestern Biology, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and educational collections at the Navajo Nation Veterinary Clinic in Chinle, Arizona (see Table S1 in Online Supplementary Material). Using a NextEngine3D scanner, the nasal and nuchal portions of the skull were scanned at a resolution of 2000 dots per inch (DPI). For each horse, the maximum extent of new bone formation at the nuchal crest was measured from a 3D model using open-source measurement software. Following criteria outlined in Bendrey (Reference Bendrey2008), we assigned a qualitative score of 1–6 to each specimen based on coverage and depth of new bone formation. In cases of a split score between the upper and lower portion of the occipital (e.g. 3/2), the average of the two values (in this case 2.5) was used in analysis. To compare these score distributions across groups, we followed this with a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance by rank and pairwise Wilcoxon sign-rank tests.

Next, the maximum depth of medial and lateral nasal grooves was measured digitally for specimens in each group. From the point of deepest groove formation, a straight line along the plane of the nasal process of the incisive bone was drawn at the point of intersection between the groove wall and the arc of the bone's dorsal surface (Figure 4). We measured groove depth perpendicular to this first line. In cases of asymmetry, we recorded the deeper of the two measurements. To account for variation in size between breeds, we subsequently normalised each measurement to the diameter of the bone in the area of groove formation.

Figure 4. Medial groove depth, measured perpendicular to the intersection of groove walls and the dorsal surface of the incisive bone, shown here on an archaeological specimen.

As environmentally stimulated bone changes may be age-dependent, demographic differences between samples might affect the observed patterns. To correct for this, we calculated an age estimate for each specimen using dental eruption and wear guides (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Jack and Jones2007). When possible, we constrained estimates based on incisor morphology with crown-height measurements of cheek teeth (after Levine Reference Levine, Wilson, Grigson and Payne1982). In cases where a precise estimate was not possible, we employed the median of the estimated age range in analysis. Whether or not a historically documented age was available, we recorded dental estimates and used these in analysis, in the hopes of maximising data comparability, and ensuring that bias was at least consistent across specimens.

Ossification scores are ordinal data, so we assessed the relationship between estimated age and nuchal ossification using a correlation test (Spearman's rho). An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) linear regression between age and groove depth helped to estimate the effects of age on nasal remodelling. Using this regression, we then calculated an age-predicted lateral and medial groove depth for each specimen. Finally, we tabulated the residual between each specimen's observed depth and its age-predicted value, and compared this age-corrected metric across groups using a one-way ANOVA and pairwise t-tests. Results for all tests are given below.

Results (nuchal ossification)

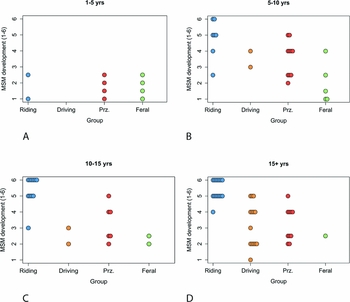

Nuchal ossification scores differ markedly between feral and zoo specimens (Figure 5). Corroborating findings by Bendrey (Reference Bendrey2008), ridden horses in museum collections had a unimodal, left-skewed distribution of ossification scores, centred on values of ‘5’ (a “bony, hypertrophic projection between 7.5–15mm in length”; Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008: 28). E. przewalskii from zoos shared this pattern, supporting the hypothesis that nuchal ossification in captive animals may be exacerbated by differences in posture, stereotypy or other captivity-related stress to the neck area. Feral horses, in contrast, tended to have dramatically lower ossification levels. A few feral horses developed extreme enthesopathy, but scores for this group tended towards values of ‘1’ (no ossification). A Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance by ranks test suggests that these differences are significant across groups (K-W χ 2 = 32.96, df = 4, p = <0.001), and pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests indicate that this significance is driven by higher ossification levels in ridden horses than in feral (p<0.001), driven (p<0.01), or zoo Przewalski (p<0.001) horses.

Figure 5. Nuchal ossification scores (1–6) for museum sample specimens from ridden horses (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008 and data from this study); driven horses (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008); E. przewalskii from probable zoo provenance (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008); ‘Prz. (1)’; horses of known zoo provenance (‘Prz. (2)’, this study) and feral animals (this study).

Nuchal ossification scores across all groups are also significantly age-dependent (Spearman's correlation test p<0.01). Feral horses in this study had a younger mean age than the ridden sample, so differences in nuchal ossification could be influenced by systematic differences in sample age. Nonetheless, a pattern of reduced ossification in feral horses appears to persist across all adult age classes except the very youngest, where all horses display similarly low scores (Figure 6). When compared with feral specimens, nuchal enthesopathy in ridden horses thus seems to be much more compelling evidence for horse transport than previously recognised. Additional study will be necessary to assess the impact of other factors, such as body size, on nuchal bone formation.

Figure 6. Nuchal ossification scores for ridden horses (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008), driven horses (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008), Przewalski's horses from European zoos (Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008), and feral horses analysed in this study.

Results (nasal remodelling)

As hypothesised, nasal remodelling also differs significantly across horses with different work histories. A one-way ANOVA (F = 9.74, p<0.001, with 2 and 28 degrees of freedom) provides strong evidence against the null hypothesis of equality in medial groove depth (Figure 7). Feral horses have a lower mean depth than ridden specimens (p<0.01), even after normalising the data to bone size and correcting for age (p<0.01). Zoo specimens show intermediate levels of medial remodelling, with deeper medial grooves than feral horses (p<0.01), and cannot be statistically distinguished from ridden specimens. Given the sedentary nature of zoo life, this nasal remodelling is probably not due to physical exertion, although it might be linked to captivity stress (e.g. heavy breathing). If so, captive equids should exhibit deeper lateral grooves than their wild counterparts. Groove measurements from one free-range Przewalski's horse are indeed markedly shallower than observations from E. przewalskii residing in zoos, providing preliminary support for this hypothesis (Figure 7).

Figure 7. A) Medial nasal groove depth across ridden, feral and zoo samples (top); B) the same data normalised to incisive bone width (bottom left); C) corrected for age using OLS residuals (bottom right).

Akin to nuchal ossification, an OLS linear regression model indicates that medial groove depth is also nominally age-dependent (p<0.01). The correlation coefficient, however, is very small (0.028mm/yr), and age explains very little of the observed variance in medial groove depth (adjusted R2 = 0.18). Most importantly, even after calculating residuals between observed and age-predicted OLS residuals, ridden horses can still be clearly distinguished from feral specimens (p<0.01, Figure 7c). Ridden animals also show an association between groove depth and nuchal ossification. In feral and captive horses with either high nuchal scores or groove depths, extreme values of the corresponding pathology do not commonly co-occur (Figure 8). This supports the contention that a common mechanism, use in transport, drives the development of both features. In contrast, variation in pathology levels among feral and captive zoo horses is probably driven by a wider range of context-specific causes.

Figure 8. Plot of medial groove depth and nuchal ossification score showing co-occurrence of high values in ridden specimens.

Among all horses, lateral grooves formed somewhat inconsistently. Nonetheless, ridden horses appear to develop them at much higher frequency (Figure 9), and a one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise t-tests indicate that ridden horses have significantly deeper grooves than feral specimens (F = 5.166, p<0.05). Similar to medial groove depth, age and lateral groove depth are loosely related (coefficient = 0.016, p<0.10, adjusted R2 = 0.07). Due to the high frequency of specimens without lateral grooves, including all sub-adult and most feral/zoo horses, regression may be a flawed technique for age-correction. Regardless, comparing OLS residuals did not remove differences in lateral groove depth between wild and ridden horses (ANOVA p = 0.07, Figure 9b). Moreover, when lateral grooving did occur, it was often matched with extreme medial depths. Among captive horses even pronounced medial grooves were not accompanied by significant lateral remodelling. As a result, it appears unlikely that inter-sample age differences are driving lateral groove patterns.

Figure 9. A) Lateral groove depth by group (left); B) after normalisation to bone width and correcting for age (right).

One mechanism that might increase the frequency of lateral remodelling is pressure on the nasal region and infraorbital nerve from bridle components, such as a noseband or cheekpiece (Figure 10). Variation in horse use and bridle morphology could explain the high frequency of lateral grooves among ridden horses, as well as their occasional asymmetry. The most extreme case of lateral remodelling observed in this study belongs to General John Pershing's warhorse Kidron, which saw active duty in the Spanish-American war. Extreme lateral remodelling is also present on horses from ancient Pazyryk (c. 600–300 BC) and Turkic (c. AD 600–800) burials in collections at the National Museum of Mongolia. Further research is needed to substantiate this hypothesis, but if lateral grooving is related to riding equipment, it may ultimately prove to be an especially valuable index of human horse use.

Figure 10. Schematic diagram of horse cranium, indicating position of simple rope halter relative to nasal remodelling, and the path of the infraorbital nerve (arrow).

These results indicate that nasal remodelling tracks both exertion and other forms of stress in horses. Further study of wild equids under high predation pressure may thus be needed before nasal pathologies can conclusively distinguish ridden from wild animals. Modern feral horses experience little in the way of predation, and might exhibit less nasal remodelling than heavily hunted populations. In contrast, horses experiencing high predation pressure in antiquity, such as pre-domesticate equids of Central Asia, would be expected to demonstrate deeper and more frequent medial grooves. These same horses, however, should also have infrequent lateral remodelling and limited nuchal ossification. Consideration of all three measures should enable the separation of equine transport from other mechanisms that might cause medial grooving or other cranial pathology in isolation.

Archaeological applications

Given the marked differences between feral and ridden horses reported here, cranial pathologies can be used to evaluate horse use in antiquity. Nasal groove depth and nuchal ossification scores provide an independent dataset for testing the hypothesis that DSK horses were used for riding or chariotry. Following the methods described earlier, we analysed a sample of 25 DSK horse crania from sites in central Mongolia, scanning these at high resolution. Eighteen of these specimens had associated radiocarbon dates, falling between 1337–769 cal BC (at 2-sigma confidence interval, see Fitzhugh Reference Fitzhugh2009c: 219–20). For those specimens with sufficient preservation for nasal (n = 9) or nuchal (n = 6) analysis, we measured lateral and medial groove depth, assigned a nuchal ossification score and estimated age for each specimen. We compared the resultant palaeopathological data from the DSK specimens with the feral and domestic samples to test the hypothesis of DSK equestrianism.

Deer Stone-Khirigsuur results

Nuchal ossification scores for the DSK sample have a mode of ‘4’ (“a bony hypertrophic projection less than 7.5mm in length”; Bendrey Reference Bendrey2008: 28). Although the sample size is small, this result is statistically distinguishable from scores of the modern feral sample (p<0.05), and consistent with values from worked animals (Figure 11a). Although DSK nuchal ossification scores appear lower than modern ridden specimens, these values are also inconsistent with those of feral horses, and their distribution is visually similar to that of Bendrey's (Reference Bendrey2008) ‘driven’ population.

Figure 11. A) Nuchal ossification score for DSK sample (top), as compared with known groups, ‘driving’ and ‘riding’ data from Bendrey (Reference Bendrey2008); B) normalised and age-corrected medial groove depth for DSK sample (lower left), as compared to known groups; C) normalised and age-corrected lateral groove depth for DSK and comparative horses (lower right).

Nasal remodelling provides stronger support for the hypothesis that DSK horses were used for transportation. A one-way ANOVA for medial groove depth between ridden, feral and DSK horses (p = 0.001), followed by Holm-corrected pairwise t-tests, indicates that the DSK sample is similar to ridden horses, and can be distinguished from the feral group (p<0.05, Figure 11b). This pattern holds even after controlling for the effects of both size (p<0.05) and age (p<0.01). As in ridden comparatives, deep groove scores correspond with higher nuchal ossification scores among DSK specimens. Lateral groove depth also occurs in the DSK sample at a high frequency similar to that of ridden horses (Figure 11c), and despite the small sample size, pairwise t-tests provide some evidence to separate uncorrected DSK lateral groove values from the feral sample (p = 0.10). Most tellingly, deep lateral and medial grooves co-occur in the DSK sample, as they did in the ridden comparatives (Figure 12). If the people of the DSK Complex were indeed equestrian pastoralists, these results would support the idea that transport activity is involved in lateral groove formation, and could implicate the use of a bridle or headgear in late Bronze Age Mongolia.

Figure 12. Lateral vs medial groove depth across groups, showing co-occurrence of high values in ridden and DSK samples.

When present, elevated levels of nuchal ossification and medial and lateral nasal remodelling appear to be robust indicators of equine transport, and may be useful for evaluating prehistoric horse use in other archaeological contexts. The compelling pathological signature identified in DSK specimens supports the contention that equine transport and increased mobility played a key role in social transformations in Mongolia and East Asia towards the end of the Bronze Age (Honeychurch et al. Reference Honeychurch, Wright, Amartuvshin, Hanks and Linduff2009; Houle Reference Houle, Hanks and Linduff2009; Wright Reference Wright2014). Chariots and riding artefacts may be absent from the late Bronze Age archaeological record in Mongolia, but the equine crania analysed here suggest that many DSK horses were heavily exerted (and perhaps bridled). Although these osteological techniques cannot reliably distinguish between chariotry, cart traction or horseback riding, the data imply that the horse was used for transport in the Mongolian Steppe as early as 1300 BC. Models for the spread of equine transport into East Asia may thus have greatly underestimated the role played by steppe peoples from the Mongolian Plateau.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the American Center for Mongolian Studies, with additional support from the Frison Institute for Archaeological Research, the Department of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico and the Society for Archaeological Sciences. We would like to thank the National Museum of Mongolia, the Museum of Southwestern Biology, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Sukhtulga Tserennadmid, Khustai Nuruu National Park and the Navajo Nation Veterinary Clinic for providing research support and access to their collections for this project. Veterinary counsel was provided by Scott Bender, Rodney Flint Taylor and Jocelyn Whitworth, while Sandra Olsen, Melinda Zeder, Bruce Huckell, William Honeychurch and Jeffrey Long provided invaluable feedback on early drafts. Equipment for scanning was provided by Heather Edgar and Michael Rendina at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, as well as the Zooarchaeology Laboratory at the University of New Mexico. Finally, this work would not have been possible without the unwavering support of James Taylor and Barbara Morrison, the mentorship of Emily Lena Jones, William Fitzhugh, E. James Dixon, and the patience and insight of Jacqueline Kocer.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2015.76