Introduction

Multiple lines of archaeological evidence affirm the existence of a unique hilltop shrine-complex, the Emerald Acropolis, dating to the eleventh century AD and 24km east of the American-Indian city of Cahokia, in present-day Illinois. The earliest religious buildings or shrines at the site pre-date the expansion of the Acropolis, although most were coeval with Cahokia's redesign and transformation into a planned city during the mid eleventh century AD. Ritual deposits, building azimuths and the overall configuration of the Acropolis relative to the larger landscape suggest the prominence of water and the moon in the Mississippian political-religious order that developed in this region. The site's pole-and-thatch architecture features rectangular and circular ‘shrine buildings’. Similarly, its 12 rectangular and circular earthen mounds were built in rows at angles that align on the horizon to either a northern maximum moonrise or a southern maximum moonset.

In the last two decades, researchers of the ‘Mississippian’ period in the American Midwest and Southeast have moved from debating scale and complexity to questions of history, identity and ontology (Cobb Reference Cobb2005; Gronenborn Reference Gronenborn, Butler and Welch2006; Alt Reference Alt and Alt2010; Blitz Reference Blitz2010; Pauketat Reference Pauketat2013a). In these discussions, an American-Indian city, Cahokia, justifiably receives priority. Cahokia was, after all, the largest, if not the earliest, settlement of the Mississippian culture. Its historical impacts on pre-Columbian native peoples across mid-America and the Southeast were profound and wide-ranging, owing both to large-scale immigration (and later diaspora) and to ‘Cahokian contacts’ in distant lands, all of which date to as early as the mid eleventh century AD (Emerson & Lewis Reference Emerson and Lewis1991; Stoltman Reference Stoltman1991; Alt Reference Alt, Butler and Welch2006; Brown Reference Brown, Reilly, III and Garber2007; Slater et al. Reference Slater, Hedman and Emerson2014; Pauketat et al. Reference Pauketat, Boszhardt and Benden2015a). Yet the basis of Cahokia's attraction, and hence the explanation of its rapid, large-scale and multi-cultural formation, has remained obscure until now.

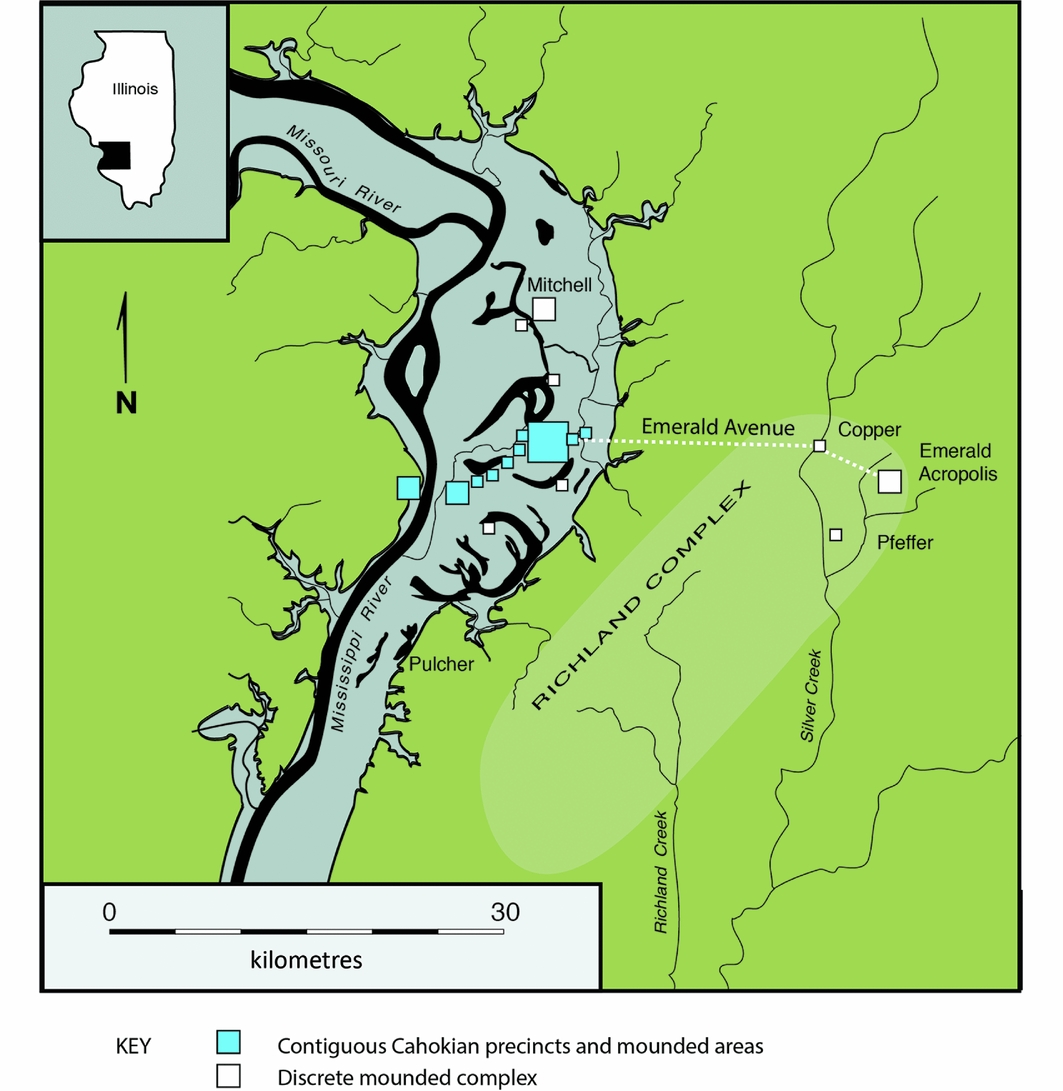

Explaining the origins of the city, with its central precinct's monumental earthen and wooden architecture covering 13km2, and its human population of some 10 000 or more people, has been the focus of many researchers for decades (Fowler Reference Fowler1975, Reference Fowler1997; Emerson Reference Emerson2002; Pauketat et al. Reference Pauketat, Alt, Kruchten and Yoffee2015b). That Cahokia was built over an earlier village settlement (c. 1050 AD) has been well established through large-scale excavations both at the settlement and across the greater Cahokia region (Kelly Reference Kelly and Smith1990; Collins Reference Collins, Pauketat and Emerson1997; Pauketat Reference Pauketat1998, Reference Pauketat2013b; Kruchten & Koldehoff Reference Kruchten and Koldehoff2008). New evidence suggests that the central Cahokia precinct was designed to align with calendrical and cosmological referents—sun, moon, earth, water and the netherworld (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2013a; Baires Reference Baires2014a & b; Pauketat et al. Reference Pauketat, Emerson, Farkas, Baires, Pauketat and Alt2015c; Romain Reference Romain, Pauketat and Alt2015). Preliminary indications suggest that Cahokians exported this cosmological order to distant lands in the mid eleventh century (Pauketat et al. Reference Pauketat, Boszhardt and Benden2015a). New evidence from the Emerald Acropolis site (11S1) suggests that it arose in conjunction with the development of this major shrine-complex (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the Emerald Acropolis, Emerald Avenue, Cahokia and other related sites (drawn by T. Pauketat).

The Emerald site and its 12 rectangular and circular mounds sit on a 12m-high glacial drift ridge, part of a more extensive Pleistocene interlobate moraine, along an intermittent stream in the middle of the historically known ‘Looking Glass Prairie’ (Willman & Frye Reference Willman and Frye1970; Oliver Reference Oliver2002). As noted by Euro-American pioneers, a prominent spring was located at the site, as was the beginning of an ancient “well-worn trail, or road” that connected Emerald to Cahokia (Snyder Reference Snyder and Walton1962: 259), now believed to have been a processional avenue (Skousen Reference Skousen2016). Alignments of mounds are visible on aerial photographs and LiDAR images, even though the hilltop site has been subjected to over a century of mechanised farming and attendant soil erosion (Figure 2). Salvage archaeology undertaken at the site in the late 1990s and again in 2011 documented intact building floors and foundations, yet low densities of habitation debris characterise both the surface and subsurface deposits (Woods & Holley Reference Woods, Holley, Emerson and Lewis1991; Koldehoff et al. Reference Koldehoff, Pauketat and Kelly1993; Alt & Pauketat in press).

Figure 2. Topographic map showing mounds (1–12), project excavation blocks, the location of the spring and borrow pit, and inferred organisational axes (image produced by J. Kruchten using LiDAR data from the Illinois State Archaeological Survey (UTM north (true north correction = −1.75°)).

Our research at the site was initiated in 2012 to investigate these characteristics as they relate to the foundations of the city of Cahokia. Over four years (2012–2015), we have produced a suite of new architectural, depositional, radiometric and settlement data that point to the following: a locality-wide lunar grid; a concentration of small habitation sites around the central complex; a dense palimpsest of rebuilt pole-and-thatch buildings; a series of intermittent occupational and construction pulses; and buried, stratified construction fills used to enlarge an artificial Acropolis (see also Alt & Pauketat in press). Based on this new information, the Emerald Acropolis now seems to have been integral to the rise of Cahokia, for reasons that are explained below.

Architecture

Between 2012 and 2015, we opened seven excavation blocks at the site, revealing the remains of 140 single-set post- and wall-trench buildings and their reconstructions. Based on these and geophysical survey data, it appears that the Acropolis itself was crowded, with between 500 and 2000 buildings during major ceremonials (Table S1 in online supplementary material). The earliest post-wall buildings date to c. AD 1000 (Table S2, Figures 3–5). Most of the rest date from the mid 1000s to the early 1100s AD, the region's ‘Lohmann phase’, and the period of Cahokia's ‘Mississippian’ redesign and expansion (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2004). Some buildings date to the early Stirling phase (AD 1100–1150), and a series of about 20 superimposed trenches for wall foundations in excavation block 5 probably post-date AD 1200 (Table 1, Figures 4 & S1).

Figure 3. Plan view of excavation block 2 showing superimposed pole-and-thatch architectural remains, including yellow-plastered-floor shrine houses and a series of temporary wall-trench style buildings (maps digitised by J. Kruchten; project grid north (true north correction = +2.39°)).

Figure 4. Plan view of excavation block 5 showing high-density superimposed pole-and-thatch architectural remains, including circular rotundas, temporary wall-trench style buildings, and yellow-plastered-floor shrine houses (maps digitised by J. Kruchten; project grid north (true north correction = +2.39°)).

Figure 5. Plan view of excavation block 6 showing high-density superimposed building remains atop earthen construction fills, including yellow-plastered-floor shrine houses, temporary wall-trench style buildings, and large post-wall council houses (maps digitised by J. Kruchten; project grid north [true north correction = +2.39°]).

Table 1. Greater Cahokia's chronological phases and regional developments.

Counting all partially or completely delineated architectural constructions and reconstructions of walls in our excavated sample, about 74 per cent of the site's buildings were simple, rectangular wall-trench houses, interpreted as temporary shelters for visitors (e.g. Figure 3). These lack interior roof support posts and storage pits, and are further characterised by low densities of artefacts or enriched fills. Unlike domestic architecture at Cahokia and elsewhere, only a few were built or rebuilt in semi-subterranean basins, with floors up to 0.5m below the ground surface, into which wall-post foundations were set.

The remaining 26 per cent of the building sample included characteristic Cahokian political-religious buildings: T-shaped ‘medicine lodges’, square temples or ‘council houses’, circular buildings (rotundas and sweat baths) and small rectangular ‘shrine houses’ built in deep basins (Emerson Reference Emerson1997; Pauketat et al. Reference Pauketat, Kruchten, Baltus, Parker and Kassly2012; Alt Reference Alt, Halperin and Schwartz2016). The latter are elaborate versions of traditional post-wall pit houses that, at Emerald, were always rebuilt in the same place at least once, if not twice, meaning that the 17 excavated examples occupied just 10 basins. With the exception of the Pfeffer site 4.5km to the south-west—a smaller mounded complex with many similarities to Emerald—rectangular shrine buildings in these numbers are unknown anywhere else in the region, including from Cahokia (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2013a). These shrine houses possess special yellow-plastered floors, hearths and small niche pits below the floors. Their basins are up to 1m deep. All but three of them have single-set post-walls; the three that did not were among the last shrines constructed at the site, and were built using wall-trenches. Materials burned inside the building basins, water-laid sediments, re-plastered floors, rebuilt walls and structured fills invariably accompanied their apparent renewal, dismantling and abandonment.

Some of the buildings in our excavations sit atop stratified construction fills, both to the east and west of the Acropolis summit (Figure S2). Their presence and associated artefacts indicate that the natural ridge upon which Emerald sits was significantly modified both at and after AD 1050. Subsequently, people built and rebuilt more pole-and-thatch architecture atop a series of artificial surfaces that, ultimately, reached depths of more than a metre, the exact extent being uncertain due to modern-day ploughing and erosion (Kolb Reference Kolb2011). The 12 mounds, including the four-sided, two-terraced, 7m-high principal pyramid or ‘Great Mound’ (mound 12) were added after AD 1050 (Skousen Reference Skousen2016). In summary, the original glacial landform was re-contoured at about AD 1050, and enlarged or resurfaced on later occasions, probably to orientate it more precisely to a celestial referent (explained below).

Unfortunately, time has taken its toll. Mounds 1 and 2 were levelled in the early 1960s, and the large pyramid, mound 12, was severely damaged by a landowner using a backhoe. At the same time, a small tumulus on its summit was mostly removed, and the area between mounds 2 and 12 was bulldozed (Winters & Struever Reference Winters and Struever1962). More recently, in 2011, highly destructive mechanised terracing of the western side of the Acropolis took place. Yet despite this destruction, the locations of seven of the site's original dozen mounds can be plotted with a reasonable degree of accuracy (using pre-2011 LiDAR data). The location of mound 1 is now apparent in new gradiometer and LiDAR plots, and the placement of mound 2 was confirmed through excavation (Barzilai Reference Barzilai2015). The positions of five other mounds, numbers 3–7, are confidently inferred based on the site's eroded topography and nineteenth-century descriptions (Snyder Reference Snyder and Walton1962). The locations of the other small mounds, especially mound 8 (which one local informant placed to the east of the principal pyramid), are less securely plotted (see Figure 2). Even ignoring these tentatively identified tumuli, alignments of the mounds with the ridge, other more distant mounds and landmarks, and the moon and sun, are apparent. Of these, lunar alignments and lunar- and water-related depositional associations are particularly noteworthy.

Alignments

Certainly, archaeologists have long suggested close relationships between early civilisations, cosmologies and astronomies (Krupp Reference Krupp1997; Aveni Reference Aveni2001; Silva & Campion Reference Silva and Campion2015). Yet the role of the moon's long, 18.6-year cycle in such developments has been debated (Ruggles Reference Ruggles1999). We now, however, have three independent lines of direct alignment evidence: 1) pole-and-thatch buildings associated with 2) mound-and-acropolis constructions, which are 3) positioned in an open prairie landscape between four natural hills. Concentrations of burnt, plastered and waterlaid materials and sediments in association with the aligned shrine buildings constitute circumstantial evidence that also supports the inference that the long lunar cycle was marked at Emerald, probably in conjunction with the annual movements of the sun on the horizon.

Lunar observations have a long history in ancient North America: linear axes of major earthworks built centuries earlier (50 BC–AD 400) by the Ohio Hopewell people were often aligned to the azimuths of maximum and minimum moonrises and -sets, among other distant landscape features, bodies of water and celestial phenomena (Romain Reference Romain2000; Hively & Horn Reference Hively and Horn2006, Reference Hively, Horn, Byers and Wymer2010). Such lunar maxima and minima occur during ‘lunar standstill’ seasons, periods of one to two years, on an 18.6-year cycle. During the maximum seasons, near the time of the winter solstice, the full moon rises and sets far to the north of the summer solstice position. Six months later, near the time of the summer solstice, the full moon rises and sets far to the south of the winter solstice position. Hence, there are four maximum (or major) horizon positions of the full moon that might be observed via the naked-eye outside the positions of the sun at its own extremes, two on each eastern and western horizon. Likewise, every 9.3 years, the full moon rises and sets within the azimuth range delineated by the summer and winter solstices, adding another four minimum positions that might be observed, again with two along the eastern horizon and another two along the western horizon (see also Sofaer Reference Sofaer2008).

In order to evaluate Emerald's hypothetical alignments, we calculated the observable rising and setting positions of the sun and moon. Owing to the different elevations and observable horizons across the Emerald Acropolis, the azimuths of the rising and setting positions of the sun and moon will vary slightly across the site. Using Wood's (Reference Wood1980: 61–64) declination values interpolated from Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1966: tab. 3), and using the base of mound 12 and the centre of excavation block 1 as back-sights, the rising and setting foresight positions of the sun's and the moon's lower tangencies at AD 1000 were calculated (Appendix S1, Tables S3–S4).

Solar measurements were taken in the field in 2012 to correct our excavation grid (and Universal Transverse Mercator north) to true north. Once corrected, we find that the locations and orientations of mounds 1, 3–7 and 12 run along a hypothetical axis (the ‘Emerald axis’), which, at 53 degrees of azimuth, matches the position of the maximum north moonrise and maximum south moonset (053.01°) to within a degree (Figure 2). To the north-east along this axis, the full moon would, around midwinter every 18.6 years, have appeared to rise from behind a natural hill known locally as ‘Blue Mound’. To the south-east and south-west, near midsummer every 18.6 years, the full moon at its maximum south extreme would have risen behind ‘Berger Hill’ and, later the following morning, set behind an apparent artificial mound atop ‘College Hill’ (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Emerald Acropolis locality, showing alignments to known mounds or landforms along the Emerald axis (maximum north moonrise at 053.01°) and the orthogonal Brown Mound-Summerfield Ridge axis (image produced by J. Kruchten, oriented to true north).

Moreover, with a vertex atop the principal pyramid, the lunar or Emerald axis and a secondary orthogonal axis intersect other distant hills and additional artificial mounds in all four directions. To the south-east, a possible artificial mound is located precisely atop ‘Summerfield Ridge’, 90° from the Emerald axis alignment, as observed when standing atop the principal Emerald pyramid. To the south-west, another possible mound is found atop ‘College Hill’ on the Emerald axis (180° degrees from Blue Mound). Brown Mound, a pre-Columbian tumulus reported in 1965 (Hall Reference Hall1965), occupies a hilltop to the north-west of the principal Emerald pyramid, 270° off from the Emerald axis or 323° from true north (see Figure S3). This is also the azimuth angle of the principal pyramid, which faces the 2m-high Brown Mound and ‘Terrapin Ridge’ behind it. Hence, both the principal pyramid's azimuth and its position on the Emerald Acropolis appear to be part of a locality-wide lunar-inspired plan. In fact, in order to obtain the vertex effect vis-à-vis the surrounding landscape, the principal pyramid had to be located precisely where it was situated. Similarly, the maximum southern moonrise occurs behind the highest point of Berger Hill when viewed from Emerald's second-largest mound, number 3 (Figure S4).

Other secondary lunar axes seem to be marked by rows of other mounds (5–7 and possibly 9–10), and mounds 1 and 2 (on a north–south line), 7 and 9, or 10 and 11 may have marked tertiary offset axes. As revealed in excavation blocks 1–7, many of the site's pole-and-thatch buildings also align to the maximum north moonrise or to other maximum or minimum lunar positions, although with considerably less accuracy (Figure S5). The inaccuracies may indicate that, as opposed to the laying out of the site as a whole, less precision was used in the construction of housing. Then again, other alignment possibilities exist for some buildings, and our ability to evaluate them may be complicated by a lack of settlement-wide data concerning the placement of other buildings and posts that might have blocked, or in other ways altered, lines of sight. Certainly, the horizon to the south-west from excavation block 1 was partially obstructed by the Acropolis itself (see sunset and moonset angles, Tables S3–S4). In addition, much like the site's principal pyramid, number 12, either the long or short axes of any given building could have been aligned, meaning that one must consider both calculated celestial positions and their orthogonals. Regardless, well over half of the pole-and-thatch constructions at the site align to within 4° of a moonrise or moonset position, with the midwinter sunrise also well represented.

Given its accuracy, we presume that indigenous astronomer-architects were on hand for the establishment of the overall site plan. This plan suggests a standard unit of measurement, as apparent in the regular spacing of the site's mounds. Distances between six of the lesser mounds correspond closely to the principal pyramid's footprint (Figure S6). The result was a “conspicuous and attractive” site whose main mound was regarded by one nineteenth-century observer as “the most perfect and best preserved mound of its class” in the region (Snyder Reference Snyder and Walton1962: 259). Just as it attracted the attention of Euro-American pioneers, so too it also appears to have captivated non-local Native Americans, whose pottery is found in association with the Emerald shrine-house deposits (Alt & Pauketat in press). They, along with native-born Cahokians, may have been among those staying in the many temporary shelters atop and near the ceremonial spaces of the Emerald Acropolis. That the earliest shrine houses atop the Acropolis pre-date both Cahokia's mid-eleventh-century expansion and the enlargement of the Acropolis itself suggests that for many people, the Emerald location possessed alluring qualities, foremost among those presumably being the fact that the lay of the land coincides at this location with the maximum north moonrise and south moonset (once every human generation). Evidence suggests that this same ridge was anthropogenically enhanced in the later eleventh century to perfect the alignments.

Water

Many of the site buildings, including the rectangular shrine houses, were eventually closed down with the aid of water. Of the 29 excavated building basins (most featuring multiple rebuilt walls), 18 (62 per cent) showed some evidence of having been closed not just with refuse, as was common among domestic sites in the region, but with water-laminated silts. In five instances, hides or mats were incinerated on building floors prior to being covered by water-redeposited silts, linking human ritual and water. Furthermore, seven shrine house basins revealed two or more distinct episodes of water deposition, sometimes separated by other burnt ritual or residential debris, similar to the two shrine houses at Pfeffer (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2013a: 175–77).

The intermittent water-laid sediments could be interpreted to indicate that the site was periodically abandoned between activity pulses, with precipitation events (e.g. warm weather rains) occurring in the interim. Three buildings, however, revealed adult-human footprints in the water-laid laminated sediments, verifying that people were also present during these depositional events. Possibly, weather events may themselves have carried significant cultural meaning connected directly to the Acropolis landform. Not only was a prominent spring located on the northern side of the Emerald ridge, but that spring also sat inside an apparent anthropogenically bowled-out feature long thought to be a ‘borrow pit’, a location from which earth was removed (or ‘borrowed’ in local parlance) to build the site's mounds (Snyder Reference Snyder and Walton1962; Fowler Reference Fowler1997). It was fed by a perched water table within the Emerald hill, a result of porous Pleistocene-age till gravels overlaid by later Pleistocene loess (Willman & Frye Reference Willman and Frye1970). This spring discharged water even when the nearby intermittent stream dried up in the summer. Moreover, in wet years, water seeps out of the sides of the ridge along this contact zone, as observed during salvage excavations in 1997 (Brad Koldehoff pers. comm. 2015).

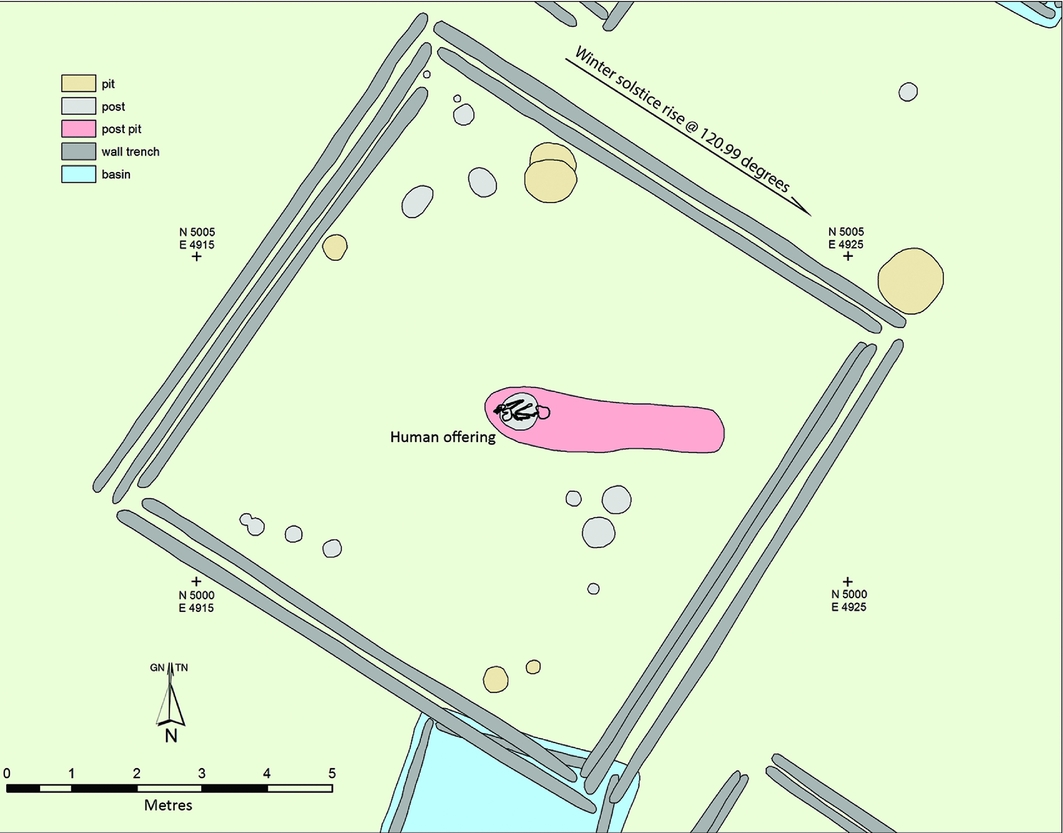

The potential cultural significance of all of the above is embodied by an extraordinary human offering, similar to several known from Cahokia's central precincts (Rose Reference Rose, Fowler, Rose, Vander Leest and Ahler1999; Hargrave Reference Hargrave and Fortier2007; Skousen Reference Skousen2012). In the Emerald case, the flexed body of a petite sub-adult or young adult of uncertain sex was placed in an open, 2m-deep post pit following the removal of an oversized 0.5m-wide upright wooden post, which had supported the roof of a temple or council house. The building, known as feature 110, was part of a larger architectural complex in excavation block 1 that faced the winter solstice sunrise (Figure 7). After the building was dismantled and the body was placed in the hole, water was allowed to wash over both the building floor and the human offering, as indicated by thick laminated silts (Kruchten Reference Kruchten2014). Subsequently, people added additional earth to bury the body.

Figure 7. Plan view of F110 and human offering in post pit (map digitised by J. Kruchten; project grid north (true north correction = +2.39°)).

Cahokian descendants or their neighbours in the Midwest and eastern Plains—Siouan speakers (Omaha, Kansa, Osage, Quapaw, Iowa and Ho-Chunk) and Caddoan-speakers (Arikara, Pawnee)—typically associated water with fertility, fertility (and femininity) with the underworld, the underworld with the moon and the night, and the moon with rain or water (Prentice Reference Prentice1986; Emerson Reference Emerson and Galloway1989). For example, the Osage and Omaha connected the moon and feminine spiritual entities with rain and water spirits (Fletcher & La Flesche Reference Fletcher and La Flesche1992; Bailey Reference Bailey1995). Among the Omaha and the Ho-Chunk, masculine water spirits resided in streams, but feminine spirits occupied the water “under the hills” (Dorsey Reference Dorsey1894: 538). Among the Pawnee, who lived up the Missouri River west of Cahokia at the time of European contact, different phases of the moon were closely connected with rain and a mythical feminine character seen as an “old woman (full moon in the east)” before turning back into a young girl (new moon in the west) (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain1982: 95). Other Caddoan speakers considered rainwater as the ‘tears of the moon’ (Miller Reference Miller1996).

The descendants and neighbours of Cahokia also related to water via circular buildings and, presumably, platform mounds. Drawing on Plains Indian analogies, Robert Hall (Reference Hall1973, Reference Hall1997) connected small, circular sweat lodges or steam baths at Cahokia and beyond to associations with water and femininity. Historically, Cahokia's Plains and Midwestern descendants and neighbours would go there for spiritual cleansing (Hall Reference Hall1997). In such buildings, water would be poured over hot rocks in puddled earthen hearths to produce steam, affording people direct engagement with spiritual powers through the richly affective experience of earth, rocks, fire, water, steam and sweat (Hallowell Reference Hallowell and Diamond1960; Bucko Reference Bucko1998; Neihardt Reference Neihardt2008).

At Emerald, three of these small, circular buildings with interior hearths overlook the low-lying ‘borrow pit’ area of the site that contained the spring noted by pioneers. In contrast, the rotunda-sized examples of buildings at Emerald have only been found atop the ridge summit. In addition, geophysical plots and excavation blocks south of the principal pyramid indicate their segregation from the smaller rectangular shrine houses (Figure S7). Similarly segregated atop the ridge summit are the circular mounds, originally described in 1891 as platforms (Finney Reference Finney2000). A drawing of mound 2 in 1881 illustrates its flat summit with enough space for the standard 7- to 9m-wide rotunda (Anonymous 1881), suggesting that these mounds were the earthen versions of—or substructure bases for—circular wall-trench buildings (Figure S8). Consistent with Hall's (Reference Hall1997) appraisal of circular sweat baths, and similar to examples from Mesoamerica, the rotundas—especially as elevated atop both the circular platform mounds and the Emerald Acropolis—may have been the Cahokian equivalents of ‘water shrines’ (Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2012).

Conclusion

All evidence indicates that the Emerald Acropolis was a special religious installation or shrine-complex situated away from a permanent stream, but in the middle of a large prairie with close proximity to a prominent spring, and at the end of a well-worn trail or processional avenue. The ridge upon which the Acropolis sits witnessed tremendous investments of labour, particularly during and following the mid-eleventh-century construction of Cahokia's monumental precincts. Given these circumstances, we infer that Emerald, with all of its aligned and elevated qualities, was key to the emergence of the city around AD 1050. At that time, the central Cahokia precinct was also re-designed. Given preliminary indications that Cahokians exported their lunar and water-based cosmological order to distant lands in the mid eleventh century, the even earlier eleventh-century co-associations of water, moon, sun, earth and feminine powers at Emerald assume causal significance. Apparently, the founding and enlargement of Cahokia and Emerald were part of an expansionist religious (if not also political) movement that underwrote what became ‘Mississippian culture’ (Blitz Reference Blitz2010; Baltus Reference Baltus, Buchanan and Skousen2015).

Acknowledgements

All data and materials derived from the Emerald Acropolis Project are curated by the Illinois State Archaeological Survey (ISAS) at the University of Illinois. We thank ISAS Director Thomas Emerson for the 2010 LiDAR data used in Figure 2. Additional LiDAR and funding for this research was provided by the John Templeton Foundation (JTF; grant 51485), by the Religion and Human Affairs programme of the Historical Society of Boston, sponsored by the JTF, and by the National Science Foundation (grant 1349157). Jeffery Kruchten produced the final versions of all LiDAR and excavation block maps. The authors are grateful to landowners Alan Begole, Walter Kunz and Edward Hock, Jr, for site access, and to William Romain for his assistance with the on-site true north grid correction in 2012. Thanks also to John Scarry and Barbara Mills for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.253