Introduction

The peoples on China's borders and beyond, the mobile pastoralists of the steppe, have traditionally been described in derogatory terms based upon comments in the early histories of the fourth to first centuries BC (Di Cosmo Reference Di Cosmo2002: 97–104). A project at the University of Oxford's School of Archaeology has worked with a different perspective, namely that China's societies and culture were stimulated and enriched by contact with the borders and the steppe. Ongoing research has examined metal chemistry (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Bray, Hommel, Pollard and Rawson2016) to track material transfers across the Eurasian steppe to China; and it has followed river routes within China and along mountain corridors in eastern Eurasia (Frachetti Reference Frachetti2012). Above all, the research has focused on the conditions that enabled the movement of materials and ideas into central China and those that inhibited them.

The China discussed here comprises the lower Yellow River and the valley of the Wei, known as the Central Plains. Over the first millennium BC, central Chinese culture was extended to the northern bank of the Yangtze. One major conclusion is that, although some essential technologies and ideas were introduced from the steppe, such as metallurgy and the management of horses (first for chariots and later for mounted warfare), these were developed in ways completely unlike such practices in their places of origin. By the third millennium BC, the inhabitants of central China had already established complex societies and were only attracted to materials from outside if these could be adapted to fit their well-embedded customs. This is the major reason why the features of what we call Chinese civilisation differ so markedly from the more traditional descriptions of ‘civilisation’ based on developments in the Near East or later in Europe.

Central China and the steppe were inevitably linked in combat and exchange. These regions are often discussed independently of each other. Some scholars have postulated a symbiotic relationship (Barfield Reference Barfield1989: 8–20). Others have concentrated on the penetration of some steppe customs, particularly the chariot, into northern China (Wu Reference Wu2013). As a result of extensive excavation in the Russian Federation (Chernykh Reference Chernykh1992; Kuzmina Reference Kuzmina2008) and China (IACASS 2003), the relationship of central China with the steppe has generated renewed study. The border area has also attracted a lot of attention (Linduff Reference Linduff, Bunker, Kawami and Linduff1997: 18–32; Di Cosmo Reference Di Cosmo2002: 49–74). Surveys have identified typological similarities of weaponry across the steppe and into the borders (Wu Reference Wu2007; Yang & Shao Reference Yang and Shao2014).

The first steps towards an understanding of what contacts across this vast region meant to China have been made in recent decades by scholars examining the ways in which cereals (wheat and barley) and metals (particularly bronze and iron) came into the Central Plains (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Mei and Rehren2009; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Hunt, Lightfoot, Liste and Liu2011; Li Reference Li2015; Linduff 2015). The wider implications of the importance of contact between Eurasia and China were drawn together by Andrew Sherratt (Reference Sherratt and Mair2006: 35–36), who noted that, had this ‘Trans-Eurasian exchange’ not existed, China might have remained as isolated from western Eurasia as the Americas were when Columbus reached the islands of the Caribbean.

Geography: the arc and central China

Fundamental to this account are the environmental and social differences of three major areas: the Eurasian steppe, the borderlands and central China, that is, the Central Plains. Across many thousands of kilometres of the steppe, pastoralists and agropastoralists were often mobile, at least seasonally, with varied practices of trade, ritual communication, political negotiation, herding and exploitation of resources (Frachetti Reference Frachetti2012). They also sought wealth and power by forming alliances, breaking them to form new ones and vying for allegiances with gifts that in themselves were also a means of spreading new materials and technologies (Kuzmina Reference Kuzmina2008: 40–70; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015: 73). The great ranges of the Pamirs, the Tianshan, the Altai and the Sayan provided many regions rich in minerals and forests that fostered metallurgy. To the north, the basin of Minusinsk was especially favoured by mountains that sheltered its steppe and agricultural land (Legrand Reference Legrand2006).

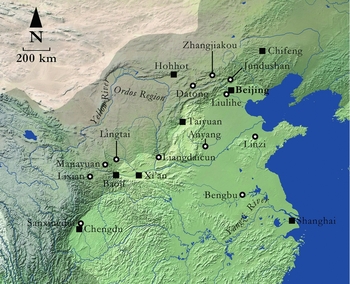

Between the steppe and the Central Plains is a vast area of high land, desert, agricultural basins and some northern forest zones, which Tong Enzheng called the ‘crescent-shaped region’ (Lin Reference Lin and Chang1986: 241–50; Tong Reference Tong1987). Others refer to it as the Northern Zone, Northern Frontier or Northern Bronzes Complex (Shelach Reference Shelach2009: 8, 28–30; Rawson Reference Rawson2015: 46–47). With different names, the area is now receiving more attention. It can be regarded as extended in the west, southwards towards Yunnan. Here, we have adopted the term ‘arc’ to describe this zone as an area of independent cultural groups (Figure 1). The arc shares with the steppe a climate generally less favourable for intensive agriculture than that of central China.

Figure 1. Central China and the arc (coloured grey, based on information on present-day herding practices) with sites mentioned in the paper. Map by Peter Hommel.

This huge, geographically and ecologically diverse area was inhabited by many different groups with varying material cultures. Three tendencies shared within the arc are relevant: weaponry, tools and metal ornaments had more in common with those of the steppe groups than with those of central China; bronze vessels, which were major products of the Central Plains, were acquired by trade or looting and were sometimes copied (Rawson forthcoming); a leaded tin-bronze alloy employed on the Central Plains was also widely adopted.

The Central Plains, by contrast, had quite different geographical and ecological features. A large territory, covered in the highly fertile loess blown from the north-west, nourished millet and rice agriculture, with few large herds, and allowed more people to be fed on the land than if it had been used intensively for pasture. This absence of herds, enabling more potential growth in the human population, is a fundamental feature of the early Chinese economy that has not been explicitly recognised before. Long before the advent of metallurgy in the second millennium BC, communities had been organised for large projects, such as the construction of ditches, dykes and walls (Shelach-Lavi Reference Shelach-Lavi2015: 127–60). The favoured grains—millet and rice—had to be boiled, not ground and baked as with wheat and barley in Western Asia (Fuller & Rowlands Reference Fuller, Rowlands, Wilkinson, Sherratt and Bennett2011: 46–51). One consequence of the intensive farming of millet and rice was that all settled communities developed a wide variety of fine ceramics for cooking and serving, and for rituals such as burial.

High levels of organisation were also fostered by the Neolithic ceramic industry in the Dawenkou and Longshan phases (fourth to third millennia BC) (Underhill Reference Underhill2002: 63, 182–84), and by the choice of jade and silk, both difficult to source and requiring specialised skills to work. Sub-division of labour had evolved before the Shang dynasty (c. 1500–1046 BC), enabling mass production of very high-quality items for elites in markedly hierarchical societies (Ledderose Reference Ledderose2000; Shelach-Lavi Reference Shelach-Lavi2015: 156–58). These were celebrated in elaborate burials, especially in third-millennium BC Neolithic societies on the east coast, emphasising the ritual roles of jade, ceramics and lacquer. The Shang and Zhou dynastic rituals that followed focused not on a distant cosmos of deities, but on kin and their afterlife powers in the here and now.

By contrast with these many sumptuous burials, those of the steppe and arc were limited in number and content. Typical of the western steppe, the well-known graves at Sintashta, east of the Urals, included weapons, ornaments and animal remains, as well as rare chariot traces (Anthony Reference Anthony2007: 374, fig. 15.3). Burials in the arc at this early stage included ceramics, some bronze weapons and ornaments (Linduff Reference Linduff, Bunker, Kawami and Linduff1997: 22–25). Despite many local variations and considerable changes in the first millennium BC, this basic division in tomb contents, with the steppe and the arc on one side and central China on the other, driven by the economies, roles and beliefs of their occupants, remained constant throughout the period under discussion.

From the steppe to China

Two major phases of change in the late third and early first millennia BC, respectively, generated movement across the steppe and had direct impact on central China. The first was a long-term expansion of activity over the third to mid second millennium BC as increasing mobile pastoralism, with wagons and metallurgy, spread across the steppe (Linduff 1998, 2015; Anthony Reference Anthony2007: 371–457; Frachetti Reference Frachetti2012). The second phase, probably starting at the beginning of the first millennium, was energised by widespread horse-riding. Here, the hallmarks of contact that can be traced in the arc and central China are the use of iron and gold, and motifs of animals, mainly in profile (Bunker Reference Bunker1993; Di Cosmo Reference Di Cosmo2002: 56–87).

Although hotly debated in the past, today scholars generally accept that metal use entered China as metallurgy, was adopted in the steppe and spread into the arc (Chernykh Reference Chernykh1992; Mei Reference Mei, Mei and Rehren2009; Linduff 2015). Some early metal finds in the arc (in the Hexi corridor and even as far east as Chifeng) are only explainable as the result of several separate contacts with peoples from different parts of the steppe (Linduff 1998). Much of this early metalwork was of arsenical copper, smelted from an ore or achieved by adding arsenic to the copper. Arsenical copper artefacts have been found in central China, but in general the peoples there chose to work with tin-bronze, to which they added lead, as some earlier casters of the Qijia culture in the Hexi corridor had done (Mei Reference Mei, Mei and Rehren2009: 10). Very high-quality tin-bronze artefacts in the steppe may have developed as a consequence of the ores available in the Altai Mountains. We do not fully understand this sudden emergence of excellent metalwork, which is known as the Seima Turbino phenomenon (Chernykh Reference Chernykh1992: 190–234). We do know, however, that it had a clear impact on China, as illustrated by a spearhead type with a projecting hook below the blade, originating in the Altai area, which was imitated, often in massive sizes, on the Central Plains (Figure 2). The repeated discovery of this unusual weapon shape in China is evidence of links with the eastern steppe (Mei Reference Mei, Mei and Rehren2009: fig. 3).

Figure 2. Central China and the eastern Eurasian steppe with finds of spearheads with hooks typical of the Seima Turbino Phenomenon, second millennium BC. Map by Peter Hommel.

Figure 3. A group of cast bronze vessels, Shang period, twelfth to eleventh century BC. Reproduced with permission of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Following the initial impetus that brought metallurgy from the steppe into the arc and then into the Central Plains, three innovations in central China illustrate concurrent reception and resistance to this introduced technology: bronze used for vessels rather than primarily for weapons; warfare conducted with steppe chariots but without individual elite combat weaponry; and jade weapons in burials, replacing the personal bronze daggers and knives buried with peoples of the steppe. All three distinguish early Chinese societies not only from those of their neighbours but also from those of the Near East.

The major Central Plains site at Erlitou, with elite structures, workshops and tombs, has provided evidence of the first shift towards using bronze in an entirely local context c. 1700–1600 BC (IACASS 2003: 61–139). Although casters continued to make some objects derived from models used in the steppe and arc (Shelach Reference Shelach2009: 128), two developments drove bronze-casting in new directions. Complex ceramic moulds were developed to cast vessels based on the ceramic prototypes already mentioned, and lead was added to the alloys to ensure that the metal flowed well into elaborately shaped and decorated forms (Figure 3). The late Shang and early Western Zhou (twelfth to ninth centuries BC) vessels were of extraordinary size, with the largest surviving vessel weighing 875kg. Sets of numerous bronzes for ritual banquet performances required immense efforts in mining, smelting, transportation, mould-making, casting and finishing (Figure 3). As bronzes were buried in tombs, new vessels were continually commissioned. The high levels of skill and the massive scale of labour and materials required for the bronze industry were driving forces in expanding the numbers of Shang centres, as well as elaborating extensive networks for the acquisition of resources, such as copper or ivory from the south and, later, horses from the north (Cao Reference Cao2014: 198–205; Rawson forthcoming).

When the Zhou, a group from the north-west, defeated the Shang in 1046 BC, they employed modified forms of Shang bronze vessels in ritual offerings and burials to establish their legitimacy and to expand their power base. All the evidence shows that, in the hands of the Shang and Zhou rulers, when metallurgy from outside was embedded in the Central Plains, it became a major instrument in enhancing Neolithic forms of ritual and thus entrenching ancient expressions of power that were unique to China.

The chariot appeared at the Shang court in the thirteenth century BC. Both the vehicle's form, with large spoked wheels, and the paired trained horses must have been introduced from the arc and the steppe, where they were first used east of the Urals in Sintashta, around 2000 BC (Kuzmina Reference Kuzmina2008: 49–59). Such a completely new machine almost certainly needed steppe drivers and trainers for the horses, and we know that these were present at the Shang centre at Anyang from copies of steppe weapons found in their tombs (Rawson Reference Rawson2015: fig. 13). These originally foreign chariots were, however, transformed for burial by the Shang elite, being decorated with local, mass-produced bronze plaques and fittings to enhance their ritual presence (Wu Reference Wu2013: figs 2.2 & 2.19).

Both the Shang and the Zhou engaged in war with their northern neighbours, as testified by oracle bones and bronze inscriptions (Li Reference Li2006: 141–92; Keightley Reference Keightley2012: 174–93). The dynastic armies did not, however, adopt northern fighting patterns, which were based on small-scale bands of men, attacking with axes, daggers, and bows and arrows (Yang & Shao Reference Yang and Shao2014). Shang leaders carried huge bronze axes, derived from Neolithic jade prototypes. Such heavy blades were not suitable for hand-to-hand combat and there was no celebration of individual valour. The distribution of short swords and daggers mapped in Figure 4 shows that these were not taken far into central China in the Shang and early Zhou periods.

Figure 4. Map of the eastern steppe and the arc showing the distribution of small swords or daggers along the arc. Minusinsk Basin (a–e): a) Krivosheino (Andronovo); b) Potroshilovo (Okunevo); c) Krasnopol'e; d) Kaptyrevo; e) Chasto-ostrovsoke; Mongolia (f–h): f) Galt, Khovshol Province; g) Battsengel, Arkhangay Province; h) chance find, Ömnögovi Province; China (i–t): i) Tianshanbeilu, Xinjiang; j) Xuhaishuwan; k) Chaodaogou; l) Baifu; m) Nanshangen; n) Shaoguoyingzi; o) Ningcheng City; p) Liulihe; q) Xi'an; r) Baicaopo; s) Baoji Zhuyuanguo; t) Chengdu. Map and drawings by Peter Hommel.

Instead, from the Shang onwards, infantry armies were large, consisting of several thousand men in the field. This number rose rapidly over the Western (1046–771 BC) and Eastern Zhou (770–221 BC) periods to tens of thousands, and, eventually, hundreds of thousands (Yates Reference Yates, Raaflaub and Rosenstein1999: 26–27). Forces of such size, as with other cultural patterns characteristic of the Central Plains, depended on a large population reliant upon raising crops, rather than herding animals.

Objects made from jade, the material most valued by the ancient Chinese, illustrate more subtle responses to the proximity and dangers of the arc and the steppe. Especially under the Shang, pointed jade blades (Figure 5), mimicking bronze weapons, in many sizes and with many different details, accompanied the highest elites in death. The dangers posed by demons and spirits of the afterlife were sufficiently alarming to require defensive weapons in jade rather than bronze steppe-style daggers—as jade was, apparently, accorded auspicious powers.

Figure 5. Symbolic jade weapons, or ge. Shang dynasty, twelfth century BC. Shanghai Museum; photograph by Jessica Rawson.

The second phase of contact and exchange can be traced from the beginning of the first millennium and intensified from the eighth century BC. Pressure from the north, which led to the collapse of Zhou rule in the Wei Valley in 771 BC and the flight of the court eastwards to Luoyang, probably resulted from increased competition and conflict in both the steppe and the arc. Many groups had taken to horse-riding for raiding and warfare and were, by then, using iron weapons (Di Cosmo Reference Di Cosmo2002: 74–90; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015: 109–56). An increasing number of conspicuous stone monuments in the steppe requiring organised labour, with burial of horse heads and installation of large upright stones, engraved with deer and with steppe-type weapons, reflected these changes between 1400 and 700 BC (Jacobson-Tepfer et al. Reference Jacobson-Tepfer, Meacham and Tepfer2010; Jackson & Wright Reference Jackson and Wright2014; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015: 112–22). In the succeeding period, 700–400 BC, steppe leaders across an immense area from the Black Sea to the arc were accorded massive burials under huge stone kurgans, along with elaborate dress with gold ornaments, belts and iron weapons, and were accompanied by horses and subordinate burials (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The steppe and Central Asia with major Iron Age sites. Map and drawings by Peter Hommel.

A concurrent dominance of animal motifs has generally been identified as Scythian in origin, but as the centre of the early development of the so-called ‘animal style’ was in the Sayan Altai region, the term Siberian or Scytho-Siberian would be more appropriate (Di Cosmo Reference Di Cosmo2002: 32). Two tomb groups are especially relevant to developments in the arc and central China: those at Arzhan in the Tuva, dating from the ninth to the seventh centuries BC (Chugunov et al. Reference Chugunov, Parzinger and Nagler2010), and those of the fourth to third centuries BC at Pazyryk in the Altai, where gold foil on wood was used, rather than solid gold (Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970: pl. 120).

Certainly the speed with which gold, iron and animal motifs reached the arc is astonishing. A lord of the minor state of Rui, buried in tomb M27, dating to the eighth century BC, at a large cemetery at Liangdaicun near Hancheng on the Yellow River, must have been a near contemporary of the individuals buried at Arzhan. Not only did the lord have iron blades set in bronze as steppe-style knives, he also had the largest assemblage of gold ornaments found so far on the edge of central China (Figure 7). The Rui lord also had a jade copy of a Tagar-type dagger in an openwork gold scabbard (So Reference So and Liu2015: fig. 3); such daggers were popular in the Minusinsk Basin and, beginning in the eighth century, appeared in many variations throughout the arc, with one example even buried in a Han prince's tomb at Mancheng, dated to the second century BC (Figure 6).

Figure 7. Suggested arrangement of gold from tomb M27 at Liangdaicun, Hancheng, Shaanxi Province, eighth century BC. Drawing by John Rawson based on a sketch of the reconstruction shown at the Shanghai Museum, September 2012.

In the fourth to third centuries BC, steppe motifs and practices from the Altai, known from the burials at Pazyryk, were transmitted enormous distances to Majiayuan in Gansu Province and other sites in the arc (Figure 6). The occupants of the nearly 60 catacomb tombs, as with their steppe contemporaries, wore gold plaques on their belts and curved ornaments around their necks; their clothes carried masses of beads, and they were interred with horse and cattle heads and hooves; none of these items figured in burials in central China (GPICRA 2014: 58–63). Their elaborate chariots were decorated with small animals that were cut out of sheets of gold, silver or tin, and that closely resembled those in felt and leather found at Pazyryk (Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970: figs 108–115, 137; GPICRA 2014: 72–84). As also seen at Pazyryk, the Majiayuan peoples took on Mediterranean motifs of palmettes and running scrolls, introduced to the steppe from Western Asia (Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970: fig. 72, pls 67, 79, 82, 143, 148, 152, 155C, 162; Stark Reference Stark, Stark, Rubinson, Samashev and Chi2012; GPICRA 2014: 88, 92, 94, 104–106).

The speed with which the Majiayuan peoples borrowed practices and motifs from the distant Altai contrasts with the resistance of the peoples of central China to adopting these. Gold was used, but hesitatingly, and with a variety of experiments with gold foil, cast gold vessels and fittings and gold inlaid inscriptions (Bunker Reference Bunker1993). Only for a relatively short period in the Western Han (206 BC–AD 6) were exotic gold and silver items highly prized (Nanjing Museum 2013). Bronze and jade remained the materials of primary value until, from the fourth century AD, Buddhism brought with it notions of jewelled and gilded paradises.

Weapons from the steppe, especially the sword, do not seem to have radically changed the tactics of war, despite having become fairly common by the sixth century BC. Some soldiers must have carried swords and employed them in battle, but there is no evidence that elite commanders engaged with swords in personal conflicts with their equals. Textual accounts suggest that swords were more likely employed in suicide, ambush or assassination (Rawson Reference Rawson2015: 70).

If, however, steppe sword-fighting and gold-ornamented dress from the sixth century BC failed to make a strong impression in the Central Plains, iron, as bronze had before, met important needs. Chinese bronze- and iron-casting was unique, with strongly controlled, very high temperatures, which were not attained farther west for over a millennium. Massive numbers of cast-iron tools enabled the central Chinese to move into more difficult territories farther to the north and south (Wagner Reference Wagner2008: 115–70). An expansion of agricultural land followed, and the rulers of the now divided Central Plains, in the period known as the Warring States (c. 475–221 BC), pushed northwards, engaging in further combat with their neighbours.

The arc and the rise of the Qin state

From the fourth to the third centuries BC onwards, the Chinese became conscious of the distinctive cultural demands of the steppe. They therefore supplied their neighbours with gold and bronze belt buckles and ornaments of a steppe style (Bunker Reference Bunker1993: 45–46). Silk was sent north, and appears in the Pazyryk tombs (Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970: fig. 17, pl. 178), but while Chinese ritual vessels were also exchanged or captured by the peoples of the arc, typical central Chinese bronze and jade forms and motifs did not, in general, find their way through the arc to the steppe.

The people there, to a large degree, and certainly the inhabitants of the wider eastern steppe, did not take up the major central Chinese innovations that had originally been a consequence of stimuli from the north: namely, bronze vessel sets, chariot ornaments in bronze and mass-production iron-casting. A fundamental reason for an indifference or barrier to these practices was a difference in ideology. In central China, offering rituals with complex bronze vessels for food and drink were linked directly to a belief in the power of the ancestors, and placed attention on social and kin relations of the living world, not on a distant cosmos. The ideologies of the arc and the steppe were not congruent, and although we have little textual information on the steppe, we can suggest that there were interests in heaven and animal spirits, ideas that later crystallised as shamanic beliefs.

In addition, large bronze and iron industries depended on a high level of organisation, as well as on complex hierarchical societies that created the demand for numerous bronze, and later iron, weapons and tools. The steppe and most areas of the arc were too sparsely populated, with limited access to resources, such as grain and minerals, to provide both the supply and consumption that drove Chinese industries forward. As a result, Chinese technologies did not go north. Much of the movement of peoples and materials came from the north or north-west towards the south. The invasion of the Zhou into the Wei River and the defeat of the Shang in 1046 BC, a battle that was fought with the support of other outsider groups, is clear indication of the drawing power of the Central Plains. And this movement towards the dynastic centres was repeated through attacks by others, known as Rong, or Xianyun, into Zhou lands during the ninth and eighth centuries BC, ultimately leading to the relocation of the capital to Luoyang in the east in 771 BC (Li Reference Li2006: 141–92).

As the Zhou moved eastwards, their territory was gained by the aspiring state of Qin. Yet, despite having taken over political centres in the Wei Valley, some early Qin lords were buried in their home territory farther west, at Li Xian, in present-day Gansu. In the eighth and seventh centuries BC, they interred sets of bronze vessels in accordance with central Chinese tradition. At the same time, some of their bronzes were embellished with small, three-dimensional animals typical of the steppe; numbers of gold ornaments, also typical of the steppe, have been found both there and in the western Wei Valley (Michaelson Reference Michaelson1999: cat. nos. 1, 2, 8; So Reference So and Liu2015: fig. 2). Over the following centuries, the Qin followed Zhou ritual practices fairly closely, but from the fourth century BC, they returned to a more hybrid combination of north-western customs in some of their tomb structures, while adopting central China's palace buildings (Shelach & Pines Reference Shelach, Pines and Stark2005: 216).

King Zheng of Qin (246–221 BC), who was to be the First Emperor (221–210 BC), took material from many regions. As he unified the territory, he employed steppe cavalry men in his army, as we now recognise from the terracotta warriors guarding his tomb (Khayutina Reference Khayutina2013: cat. no. 314), whose dress resembles that of the steppe leaders known to the Achaemenids and Parthians (Curtis Reference Curtis2000: front cover), but he proclaimed his conquest in the language of the Central Plains: Chinese. The First Emperor must have had advisors who knew something of the seals, weights and measures of Central Asia and Iran (Khayutina Reference Khayutina2013: cat. nos 115–17), and also retained craftsmen who had mastered Western technologies and cast bronze birds for his tomb in hitherto unknown life-like forms (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Chen, Shao, Yang and Sun2014). He also exploited mounted horsemen and iron weaponry originally from the steppe, and agriculture and settlements of the Central Plains, turning to the extraordinary organisation of people and manufacturing from this area to create a unified state. This could only be achieved by moving towards the centre, as the Emperor indeed did.

As the Qin moved south and east, as the Zhou had done before them, they adopted central Chinese organisation. Later dynasties founded by outsiders did the same. Yet even though northerners might take over as rulers of the Central Plains, the materials, technologies and ideas that they brought with them were only embedded there when these could be adapted to and integrated within the dense, highly organised, hierarchical societies that had come into being long before the arrival of metallurgy from the west. As close neighbours, the peoples of central China, the arc and the steppe were inevitably embroiled with each other, but throughout their continuous engagement, their cultures remained steadfastly distinct.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Leverhulme Trust Grant F/08 735/G for work by Peter Hommel, Beichen Chen, Yiu-Kang Hsu and Rebecca O'Sullivan; the research has also been supported by the Reed Foundation and the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou. The author is grateful for suggestions and information from Yuri Esin of the Khakassian Research Institute, Abakan, and for advice and information from Chris Gosden and Robert Harrist.