Introduction

Iconic rock art sites are characterised not only by the strength of their visual impact and the complexity of their art, but also by interpretations that deeply inform developments in archaeology. Often, they are deeply researched over a long period.

When, in 1977, Macintosh published a reappraisal of his earlier (Reference Macintosh1952) article on Beswick Creek Cave in the Northern Territory, Australia, his cautionary tale against ascribing meaning to rock art motifs engendered the site with iconic status. His reassessment of his initial identification of species in the rock art of the site of Doria Gudaluk (renamed by himself and by Elkin (Reference Elkin1952) as Beswick Creek Cave) demonstrated that the “mental code of the artists’ schematisation cannot be cracked without keys provided by highly initiated informants” (Macintosh Reference Ucko1977: 197). Macintosh concluded that: “If one had intended to set up a designed and controlled experiment as in a laboratory, for the purpose of testing validity of interpretation, one could hardly have staged a more perfect experiment, giving a more significant result” (Macintosh Reference Ucko1977: 197).

Based on a visit to this site in May 1952, Macintosh (Reference Macintosh1952) originally published a full inventory of the motifs at Doria Gudaluk and identified the species depicted. His reappraisal compared his interpretations with those of Elkin (Reference Elkin1952), who had been on the same field trip but had stronger relationships with the local community. Macintosh found that 90 per cent of his initial subject identifications were incorrect. As an anatomist, he found this especially perturbing. His study was critical to the development of rock art research because it demonstrated that the identification of representational meaning in figurative paintings is problematic without local knowledge.

The archaeological community took Macintosh's reappraisal to heart. Maynard (Reference Maynard and Mead1979: 86) reflected upon Macintosh's experience to contend that meaning is always “highly specific and usually esoteric” and, as such, is “probably completely intractable”. Clegg (Reference Clegg1978) argued against constructing the meaning of motifs, as it is impossible to ascertain securely either the subject or motivation of the artists. Clegg and others (e.g. Franklin Reference Franklin1984) adopted the typographic convention of an exclamation mark before their own categorisations of motifs to emphasise their view that the names allocated to motifs may not reflect the intentions of the artists, referring to !fish, !tracks and so forth. Clegg's point has been absorbed into the contemporary rock art literature: few scholars today would argue for definitive interpretations of either subject or motivation in rock art. As Morphy (Reference Morphy and Morphy1989: 1) observed, there is an important gap between the motifs depicted and the cultural concepts that they may represent. This understanding is embedded in studies of how Aboriginal peoples attribute meanings to art in other, neighbouring parts of northern Australia (Lewis Reference Lewis1988; Morphy 1991; Taçon et al. Reference Taçon, Mulvaney, Ouzman, Fullagar, Carlton and Head2003; Domingo Sanz & May Reference Domingo Sanz, May, Salazar, Domingo Sanz, Azkárraga and Bonet2008; May & Domingo Sanz Reference May and Domingo Sanz2010; David et al. Reference David, Barker, Petchey, Delannoy, Geneste, Rowe, Eccleston, Lamb and Whear2013), as well as in the theoretical works of Conkey (Reference Conkey and Soffer1987), Gell (Reference Gell1998) and Hodder (Reference Hodder1989), among others.

To reduce rock art research to the study of meaning is, however, to overlook information on past cultural developments, practices and interactions that can be obtained through descriptive, quantitative and archaeometric analysis (Domingo Sanz 2012: 307). Rather than seeking meaning per se, current approaches to rock art research focus on archaeological analyses that consider the distribution of designs within Palaeolithic societies (Farbstein & Svoboda Reference Farbstein and Svoboda2007); determine style through differences in the representation of particular motifs (Pigeaud Reference Pigeaud2007; Domingo Sanz Reference Domingo Sanz, Domingo Sanz, Fiore and May2008); analyse the art in context, in terms of either the site (Ross & Davidson Reference Ross and Davidson2006; Moro Abadía & González Morales 2007; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Campbell and Franklin2015), the landscape (Bradley Reference Bradley1997; David Reference David2002; Domingo Sanz et al. Reference Domingo Sanz, Fiore, May, Domingo Sanz, Fiore and May2008; Lenssen-Erz Reference Lenssen-Erz, Domingo Sanz, Fiore and May2008) or possible social relations, such as gender (Goldhahn & Fuglestvedt Reference Goldhahn, Fuglestvedt, McDonald and Veth2012; Hays-Gilpin Reference Hays-Gilpin, McDonald and Veth2012); or use ethnographic, oral history and linguistic data to understand the art (Merlan Reference Merlan1989; Smith 2008; Blundell et al. Reference Blundell, Chippindale and Smith2011).

In this article, we provide a fresh level of analysis of the rock art of Doria Gudaluk and present data that show that the tradition of rock painting continued at this site long after Macintosh recorded the art in 1952. We identify new motifs that were added after Macintosh's and Elkin's visits and, most probably, after the site was visited by Graham Davidson, an historian, in 1976. We analyse the cultural significance of these motifs as well as the evidence they provide for cultural continuity and change during a period when it was assumed that Aboriginal cultural practices were dying out (May Reference May2008: 93).

This article emerges from fieldwork undertaken annually from the early 1990s to 2016. During the early period, the authors, Claire Smith (who was conducting her doctoral research on Aboriginal art in the region) and Gary Jackson (an anthropologist), visited Doria Gudaluk on many occasions in the company of the senior traditional custodians Paddy Babu, Lily Willika and Peter Manabaru, and with the senior traditional owner Phyllis Wiynjorroc, daughter of Charlie Lamjorrotj (identified by Elkin (Reference Elkin1952) and Macintosh (Reference Macintosh1952) as ‘Lamderod’). We follow linguist Francesca Merlan in spelling this name as Lamjorrotj, and the site as Doria Gudaluk (pers. comm. 22 July 2015). In 2001, co-author Inés Domingo Sanz joined the research team. Recently, our first teachers and mentors have passed away. Now we visit the site with their descendants, particularly with Nell Brown, the daughter of Phyllis Wiynjorroc, and Rachael Willika, the daughter of Lily Willika. Children from the Barunga community accompany us, developing their cultural knowledge and reinforcing links with their country.

While some of the changes recorded in this article were observed as early as 1990, the publication of this article was delayed by our concern over cultural sensitivities. One critical issue was a cultural restriction on females reading the papers by Macintosh and Elkin. This issue was dealt with by the male author of this paper, Gary Jackson, whiting-out material identified to him as sensitive by senior custodian Peter Manabaru, to make the material accessible to the female authors. The current article does not contain culturally sensitive material. It focuses on change and continuity in rock art traditions at Doria Gudaluk.

The site

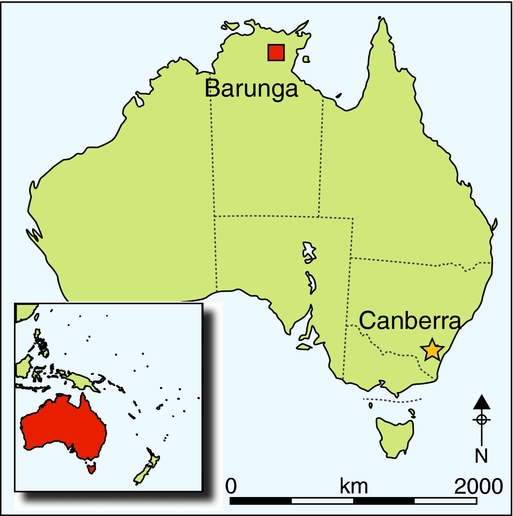

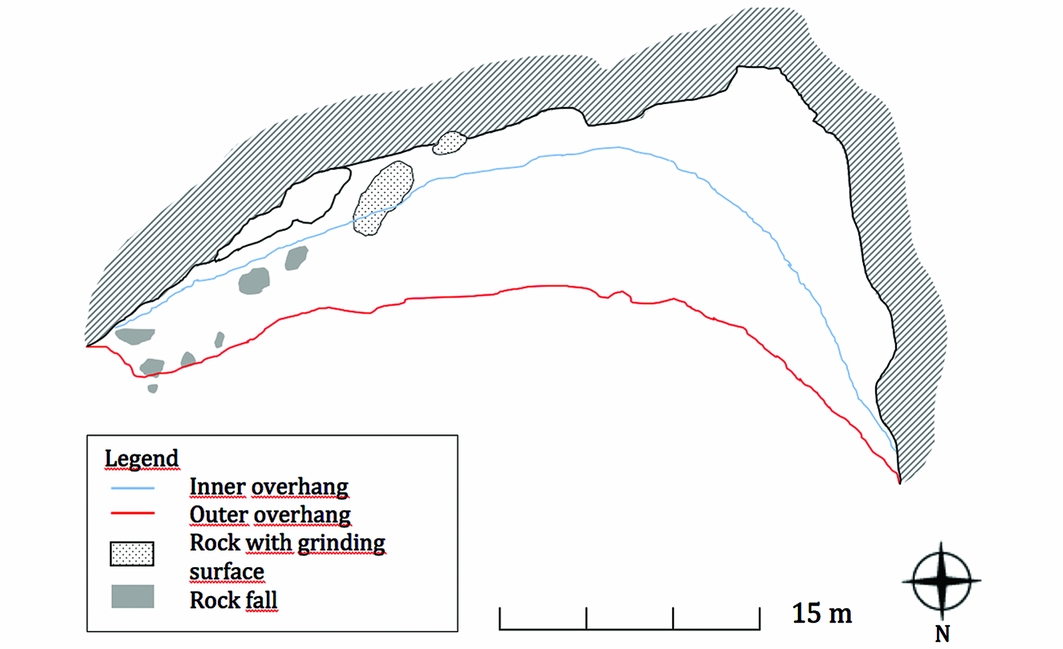

Doria Gudaluk is a large and imposing sandstone rockshelter near the Aboriginal community of Barunga in the Northern Territory of Australia. It is about 100m from a spring that contains permanent water, and has a wonderful panoramic view of the surrounding countryside (Figure 1). It is around 44m long, 7m wide at the dripline and 10m high at the centre (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Panoramic view of Doria Gudaluk.

Figure 2. Site plan of Doria Gudaluk.

Until the 1960s, Doria Gudaluk was used as both a ceremonial site and as a place that could be visited by families. Aboriginal people in this area were nomadic until the 1950s. During these times, the site was visited regularly, especially during the wet season, between November and March, when it served as a shelter. As at other Australian Indigenous places (see Ross & Davidson Reference Ross and Davidson2006), the rock art at Doria Gudaluk has a role in rituals relating to death. Bundles of cloth placed in the shelter have unravelled to show human long-bones that have special cultural significance in the local Jawoyn culture; a human skull has been placed in a high alcove. Leaving these remains undisturbed is a condition of our site visits.

Although it is a large rockshelter, it is difficult to find Doria Gudaluk, as it cannot be seen from the top of the escarpment (Figure 3). This makes it suitable for hosting secret ceremonies, and important women's rites were held here (Phyllis Wijunjorroc pers. comm. 1992). At such times, the site was closed to general visitation. Doria Gudaluk's overhanging structure also makes it a suitable place in which to hide. During the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, light-skinned Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families (Australian Human Rights Commission 1997). During this period, Doria Gudaluk was used to hide children from mounted policemen or patrol officers, as recounted by Phyllis Wijnjorroc and Lily Willika (pers. comm. 1992). Such memories imbue the site with meaning and significance that is not necessarily related to rock art.

Figure 3. View from the top of the escarpment above Doria Gudaluk.

Change and continuity

At Doria Gudaluk, testimonies of change and continuity are found both in the art assemblage and in the archaeological context (including the preserved human remains). During his1952 visit, Macintosh compiled an inventory of the motifs at the site, comprising 81 figures (Figure 4). This number was later validated by Davidson (Reference Davidson1981: 38) based on his site visits between 1973 and 1976.

Figure 4. Macintosh's recordings of motifs at Doria Gudaluk (from Macintosh Reference Ucko1977; © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies).

In July 1992, Peter Manabaru, Lilly Willika, Claire Smith and Gary Jackson checked each motif at the site, identifying those not referred to by Macintosh, Elkin or Davidson. From 2006 to 2015, Inés Domingo Sanz applied digital photographic enhancement techniques to reveal additional motifs. This recording process was completed in July 2015. In all, we identified 160 motifs at Doria Gudaluk, comprising 153 paintings and 7 concentrations of engraved lines, circular holes and areas with abraded surfaces (not counted as individual motifs). In addition to extending the Macintosh and Davidson records, this new inventory also expands the number of motifs identified by Gunn and Whear (Reference Gunn and Whear2007: 25) on a brief site visit in 2006 (107 paintings plus 50 abraded motifs and a single pecked pit).

Our analysis revealed that four motifs recorded by both Macintosh and Elkin in 1952 (white leaf 16, white crocodile 44 and hand stencils 66 and 67) had disappeared by 1990. We did, however, discover a number of new motifs. Here, we concentrate on those at the western end of the site that we think were created between Elkin and Macintosh's visits in 1952 and our own first visit in 1990. In doing so, we take into account Davidson's (1981: 38) declaration that “there are no additions to the paintings that were described by Macintosh and [Elkin]”, based on his visits to the site between 1973 and 1976.

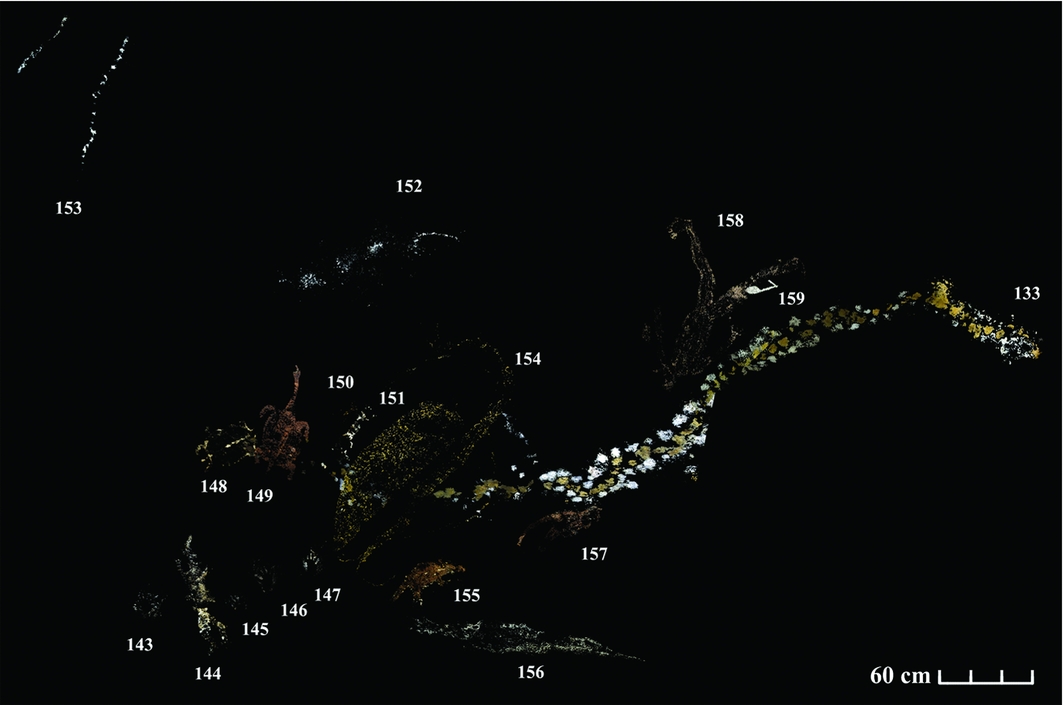

Where Macintosh identified three motifs, we have identified 28 (Figure 5). Some are faded and were probably overlooked; others can be clearly identified and are likely to have been produced after Macintosh and Elkin visited the site, possibly after Davidson's visits in the 1970s. As these motifs are located in the far corner of the site, it is, however, possible that Davidson did not clamber up into this area and may have overlooked them.

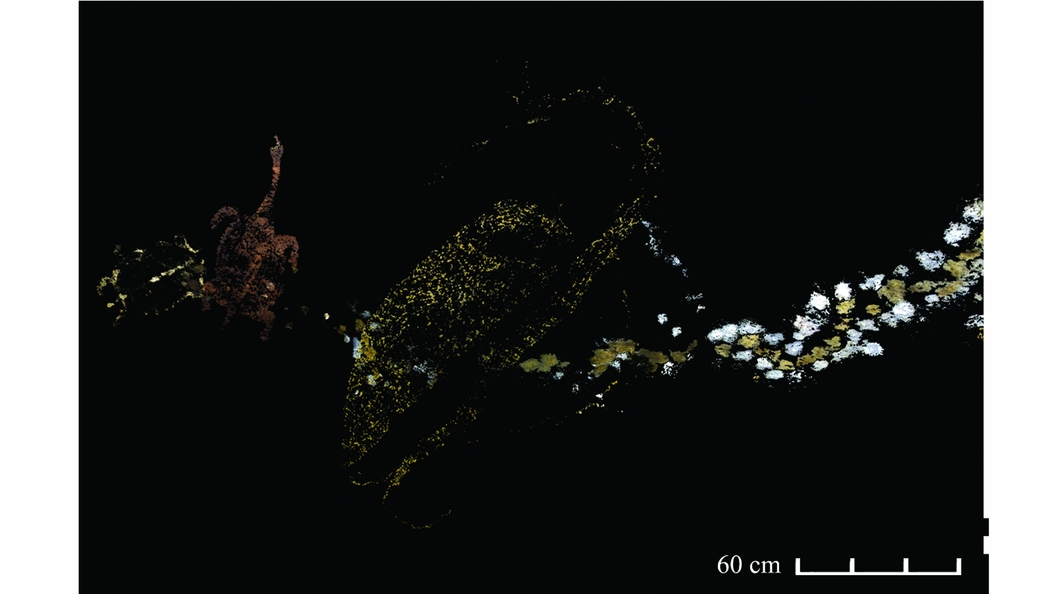

Figure 5. Motifs at the western end of Doria Gudaluk, probably added between 1976 and 1990. From left to right: white short-necked turtle, red long-necked turtle, unidentified yellow figure and part of the Bolung.

The new motifs in the western part of the site include four white hand stencils (143, 145, 146 and 147), where Macintosh had recorded only one, and motifs identified by Peter Manabaru as a long-necked turtle painted with red ochre in solid and stroke infill (no. 149); a short-necked turtle painted in white (no. 148); and a Bolung (no. 133), a creation being also known as the rainbow serpent. Other additional motifs appear to be of macropods, fish and anthropomorphs, but we have not specifically identified these, following the lessons of Macintosh (Reference Ucko1977) and Clegg (1987). Here, we focus on images that are clear and accessible, and that we feel Macintosh and Elkin could not have overlooked (including the Bolung, the short- and long-necked turtles and an unspecified yellow motif) (Figure 6). The question arises as to whether they were produced before or after Davidson's visits to the site in the 1970s.

Figure 6. Partial view of motifs added to the western end of Doria Gudaluk after site visits by Elkin, Macintosh and Davidson.

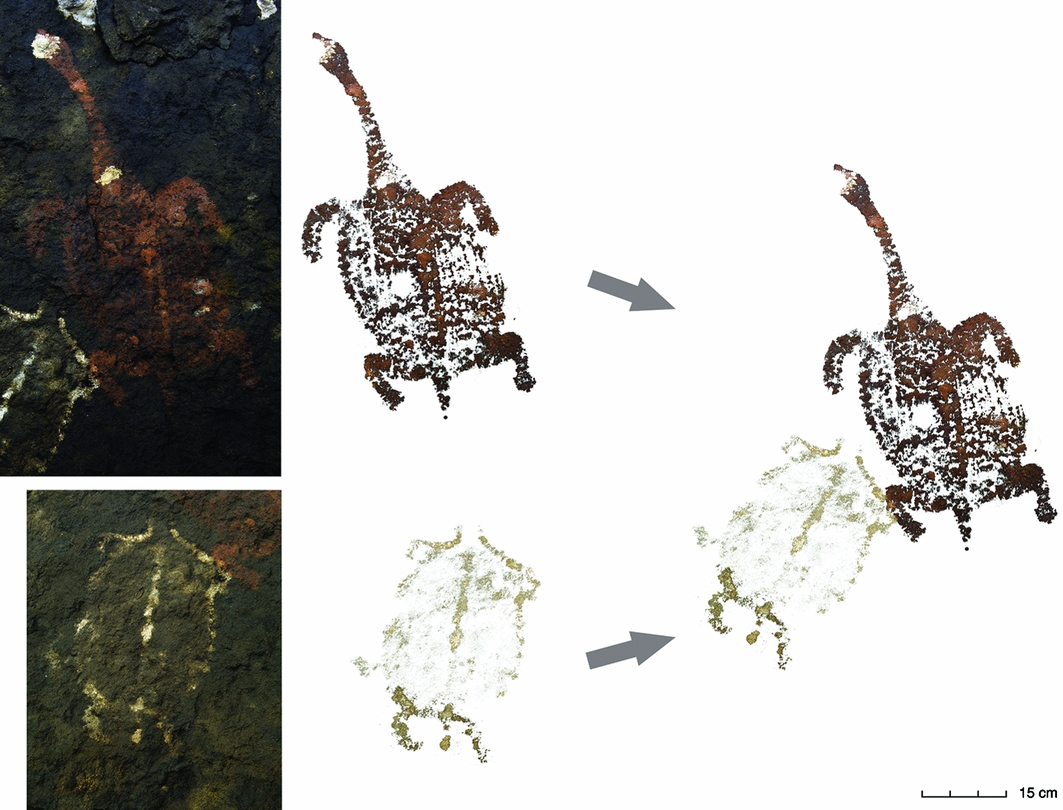

We had difficulty identifying two of the three motifs that Macintosh recorded in this part of the site. We could not find 45, a frog outlined in white, but there are five images infilled in white that could be a frog. The infill may have been undertaken after his site visit. Similarly, we could not locate image 46, described as “an incomplete outline”, which appears to be the size of a hand stencil (see Figure 4), although Lamjorrotj agreed with Macintosh's drawings and proportions when they visited the site together in 1952 (Macintosh Reference Ucko1977: 191). There is, however, a large, yellow image (our no. 154, Figure 5; shown in more detail in Figure 6), infilled in the same area, which may have incorporated Macintosh's motif 46. (We note that the proportions of motifs in Macintosh's drawings are consistent with those of other motifs at the site.) Either image 46 has disappeared or it was incorporated into the larger motif, indicating plasticity in the creation of rock art motifs.What can these new motifs at the western end of Doria Gudaluk tell us about change and continuity in cultural traditions? One approach is to interpret the art in terms of the Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties (Figure 7) that underpin the cultural structure. When Bolung, the rainbow serpent, created the earth, it fashioned the earth and its creatures with differing colours. Some land and creatures were associated with light colours (Yirritja), and others with dark colours (Dhuwa). These relationships are elegantly balanced. For example, the black cockatoo is Dhuwa, while the white cockatoo is Yirritja. In addition, the Dhuwa moiety is associated with things that are short, and the Yirritja moiety with things that are long. Thus, while the short-necked turtle is Dhuwa moiety, the long-necked turtle is Yirritja moiety. This observation is of interest to the archaeological study of rock art as it confirms the use of stylistic features (colours and subject matter) to signify social identities.

Figure 7. Relationships between Dhuwa and Yirritya moieties, colour and length.

Doria Gudaluk is on Dhuwa country and is of Dhuwa moiety. The complexity of stylistic conventions and the continuity of cultural traditions at this site are demonstrated in some of the new depictions, such as the turtles shown in Figure 8. Depiction of the short-necked turtle in white at a Dhuwa, red-affiliated site concurs with the rule of Dhuwa and Yirritja being joined together (‘in company’). In contrast, it appears that the depiction of the long-necked turtle in red at this Dhuwa, red-affiliated site contravenes the rule of joining Dhuwa and Yirritja. The long-necked turtle is of Yirritja moiety however, so its depiction in red conforms to the rule of joining moieties. Moreover, the placing of a white, short-necked turtle next to a red long-necked turtle also conforms to the social rule that Dhuwa and Yirritja should be together. There are, however, other stylistic differences in how each motif is depicted, most clearly in a comparison of the white outline and red solid infill. As stylistic techniques, and even the right to produce particular motifs, are inherited, this suggests that different artists painted each of these motifs, even though they may have been depicted at around the same time.

Figure 8. The red long-necked turtle (Dhuwa) and white short-necked turtle (Yirritya) exemplify the complexities in interpreting motifs according to the ‘simple’ categorisation of moiety.

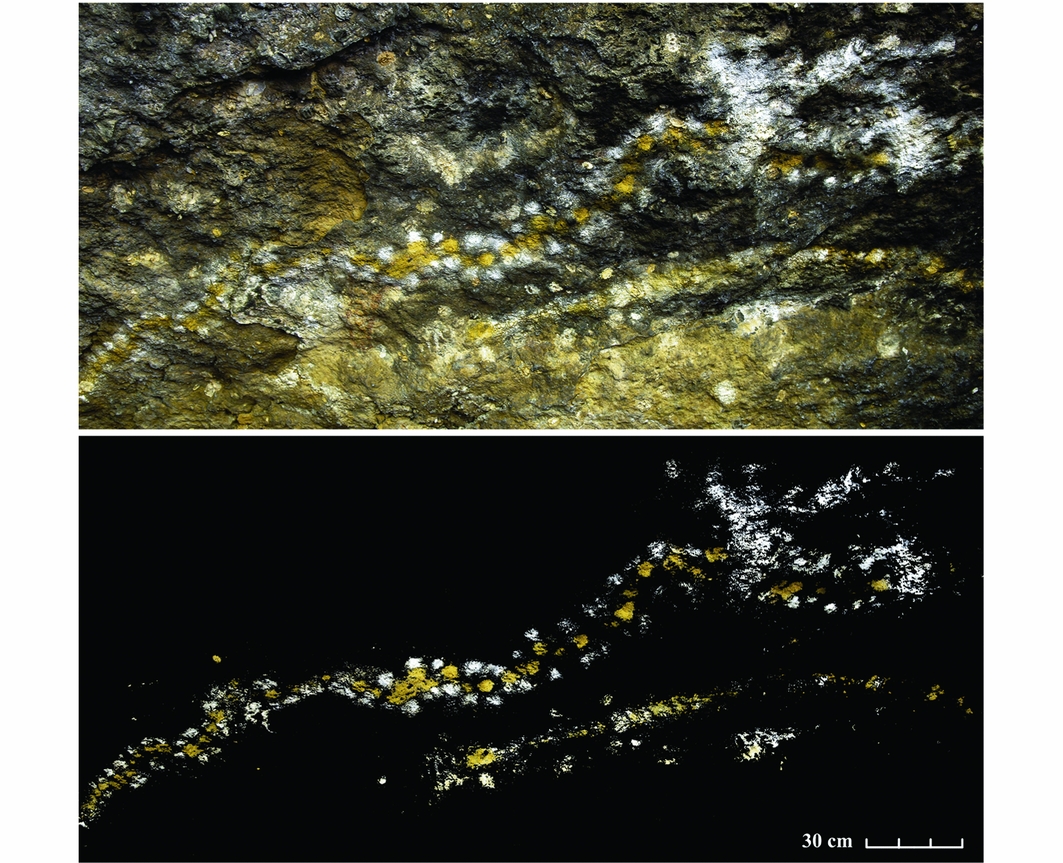

The most striking material manifestation of the endurance and potency of the artistic system is the depiction of a Bolung, also known as a rainbow serpent or rainbow snake. This image measures 20m in length (Figure 9). It was created in much the same way that a hand stencil is produced, using the mouth to spray paint onto the rock. This Bolung image travels along the wall at the western end of the site and has a dotted infill in yellow ochre and a white dotted outline. While it is long and impressive, the motif is faint in some parts and disappears for short sections.

Figure 9. Partial view of the Bolung, the rainbow serpent.

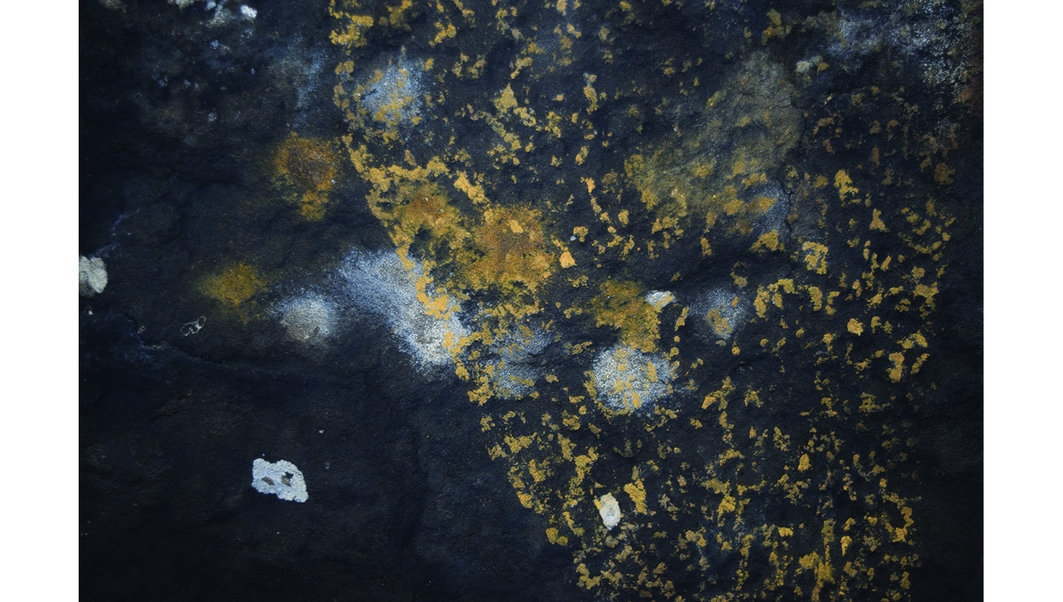

Neither Macintosh nor Davidson recorded this extraordinary motif. Given the clarity and length of the motif, it appears that the image was produced after Davidson's last visit to the site in 1976. While there are other faded or unidentified images that Davidson may have overlooked, the Bolung is imposing, and has sections that are clear and well preserved. Furthermore, the red long-necked turtle (no. 149) and the infilled yellow image (no. 154) are superimposed upon the Bolung (Figures 5 & 10). This suggests that at least four images at the western end of Doria Gudaluk were produced after 1976. In our view, the associated image of the white short-necked turtle (no. 148) was also produced after 1976. There are also, however, a number of new motifs that are small, faded or can only be identified in certain light. Either these motifs were created prior to 1976 and were overlooked by Davidson, or they were produced after 1976. On current evidence, we cannot be sure.

Figure 10. Detail of superimposition of the red long-necked turtle motif and the yellow infilled motif over the splash-spotted rainbow serpent Bolung.

Continued cultural use of Doria Gudaluk after the visits by Macintosh, Elkin and Davidson is reinforced through the presence of the human remains at the site: a bundle of human long-bones, which has become unwrapped over the last 25 years, and a human skull located on a prominent ledge near the entrance. It would be difficult to visit this site and not notice the skull. This appears to be a post-1976 addition, as Davidson records that “There were two sets of bones at the eastern end of the cave and a number of old rags and one set of bones at the western end. The bones did not include skulls” (Davidson Reference Davidson1981: 38). These bones are of great cultural import. Nell Brown (pers. comm. 20 July 2016), the granddaughter of Lamjorrotj, states that:

We are not allowed to go near that skull, or those bones. We can feel it, like we are being watched by someone, or if we go back home, we might dream about it, telling us not to go near those bones, or we'll get sick. We got to keep that in our minds and in our hearts not to go near that cave, keep near the river, like fishing. Kids can go there only with old people, but not to interfere with those bones, like touching them or making noise. They don't like noise. Them bones are sometime mimi [spirit people] or really old skeleton in paperbark, ceremony way. You know that if you see paperbark wrapped around them, they are very, very old bones.

Elkin (Reference Elkin1952: 246) states that human remains were placed at Doria Gudaluk as “a temporary depository”, one part of a multi-staged burial process. The particular human remains at such sites can change over time, as they are moved to another stage of the ceremony. The next stage of burial rites, known as a Lorrkorn (‘Loragan’ according to Elkin Reference Elkin1952: 246) ceremony, involves the person's spirit being called back to their bones and those bones being placed inside a hollow log. This rite was not enacted for the bones at Doria Gudaluk, possibly due to the expense of Lorrkorn ceremonies or to a decision to have the cave itself act as the ossuary. Lorrkorn ceremonies occurred in the Barunga region in the late 1990s. That cultural knowledge still exists, both in the region and in other parts of Arnhem Land. The ongoing presence of human remains indicates, however, that this cultural process was interrupted at Doria Gudaluk.

Discussion

This article presents new information on a site of key interest to rock art research internationally. Macintosh's Reference Ucko1977 reappraisal of Doria Gudaluk provides a clear demonstration that meaning cannot be obtained without the assistance of informed people. In addition, Doria Gudaluk is important because it provides a baseline against which cultural change and continuity can be assessed. In 1952, Doria Gudaluk was inventoried by Macintosh as having 81 motifs, a number confirmed by Davidson in the 1970s. If we accept that Davidson checked all of Macintosh's recordings, including those at the western end of the site, as he states (Davidson Reference Davidson1981: 38), it would appear that the new motifs we observed were produced between 1976 and 1990. Many are faded, however, and are visible only in certain light and so may have been overlooked. Other new motifs were found only through the enhancement of digital images (which were checked at the site) and would have been impossible to identify without the benefits of current technology. Nevertheless, some of these new motifs are both clear and accessible. These motifs were produced after 1952 and, most probably, after 1976. It is unlikely that Davidson could have missed the Bolung image, given that he visited the site specifically to check Macintosh's recordings.

Accordingly, our view is that the tradition of rock art creation continued at Doria Gudaluk until shortly before 1990. In 1952, Elkin's (Reference Elkin1952: 246) view was that the crocodile (Macintosh's motif 44) “had been painted in white in a central position in the cave quite recently”, and that “this is also evidence that the cave is still being used as a gallery”. Furthermore, Macintosh (Reference Macintosh1952: 256) writes that Lamjorrotj stated that the “cave was still in use, that natives still went there every year, that anyone could go, including women” and that “a brand new woven dilly bag had been placed on one of the ledges since the previous Sunday”. Our conclusion that the site was used continuously is reinforced by the presence of the previously unrecorded human skull.

The rock art of Doria Gudaluk needs to be understood in relation to the movements of Aboriginal populations in the region and external pressures from non-Aboriginal colonisers. Major changes occurred when the local Maranboy mine was established in 1913, and these intensified during the 1940s and 1950s (Smith 2004) when Aboriginal people from central Arnhem Land moved south onto Jawoyn lands. This created new generations of non-Jawoyn Aboriginal people who were born on Jawoyn lands. The number of Jawoyn people living in the area was severely reduced (Smith 2004: 18–41), and non-Jawoyn people took on Jawoyn traditional cultural responsibilities. During this period, Dalabon people (the Ngalkpon language group), whose traditional lands are in central Arnhem Land, became the traditional custodians for sites in this part of Jawoyn country: Peter Manabaru, Paddy Babu and Lily Willika were all Dalabon people of Yirritja moiety.

These social changes are reflected in the rock art at Doria Gudaluk. The splash-spotting technique used for the Bolung motif is unusual in this region but is a dominant painting technique in Dalabon country in central Arnhem Land, where it is combined with a white outline (see Maddock Reference Maddock1970). The presence of this technique suggests that Dalabon people were actively engaged in ceremonial activities at the site in the period after 1952. In this light, the Bolung motif is physical evidence of an important cultural change as custodial responsibility for sites transferred from Jawoyn people to the Dalabon. This process shows that cultural competency was more important than language affiliation, being Jawoyn or Dalabon. Responsibilities moved naturally to people who had the deepest cultural and ceremonial knowledge, irrespective of their language group. Jawoyn people, however, remain the unchallenged traditional owners of the land, even when people from another language group hold much of the key cultural knowledge. Indeed, Jawoyn leaders would have had to approve this change. Both Elkin and Macintosh emphasise the authority and respect held by Jawoyn senior traditional owner, Charlie Lamjorrotj, at this time. Lamjorrotj must have endorsed the changes in custodianship as part of his oversight, ensuring cultural resilience during a period of rapid change and unprecedented challenges.

This article has important implications for stylistic analyses of rock art. Firstly, the inclusion of new motifs at Doria Gudaluk from 1976 to 1990 indicates the existence of a strong and dynamic artistic system at a time when Aboriginal cultural practices were under threat (May Reference May2008: 93) and it was assumed that rock painting had died out in Australia (Layton Reference Layton1991). Moreover, the art provides evidence for the adaptability of Aboriginal culture, most notably through the introduction of a fresh technique in the impressive 20m-long depiction of the Bolung snake. For archaeologists, the important point is that change in the cultural system (in this specific case, changes in artistic patterns, as evidenced through the introduction of a new artistic technique) does not necessarily indicate the existence of a replacement population, as we might normally infer. Stylistic changes have been used as a diagnostic trait to identify archaeological cultures and create artistic sequences (Breuil Reference Breuil1952; Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1968). As Whitley (Reference Whitley2011: 73) points out, however, the cultural-historical notion of style needs further analysis, and different styles can coexist within the same culture (Layton Reference Layton1991: 151). Changes in the rock art of Doria Gudaluk reflect the influx of a population and a realignment of ceremonial responsibilities and power relations, as well as indirect contact between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. These changes came about as part of a system of cultural collaboration, rather than due to the replacement of one form of cultural practice with another.

This article presents evidence that rock painting at Doria Gudaluk continued from 1976 to 1990. Both change and continuity are evident in the rock art through the choice of colour, techniques of application and subject matter, as well as in associated archaeological remains. While the tradition of rock painting had ended at Doria Gudaluk when we visited in 1990, it continued in other contexts (Smith Reference Smith1992) and other media (Smith 2008). Aboriginal people have been in northern Australia for around 50000 years (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Jones and Smith1990), and have produced rock art for at least 28000 years (David et al. Reference David, Barker, Petchey, Delannoy, Geneste, Rowe, Eccleston, Lamb and Whear2013). Between 1976 and 1990, at Doria Gudaluk, one of the longest continuous cultural traditions within human evolution underwent a major transformation within a social context of cooperation, where there might have been conflict. The creation of rock art was replaced by art production in different media as Doria Gudaluk's ceremonial role ceased. Its role in community education continues, however, in the new contexts provided by a changing world, with an emphasis on familiarising children with the cultural landscapes beyond their communities (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Marlene Lee, great-grandaughter of Lilly Willika and Peter Manabaru, on an archaeological site visit to Doria Gudaluk in June 2014.

The implications of this research go beyond this case study. The data speak to a fundamental question in archaeology: relationships between population movements and the transmission of ideas. Archaeologists have sought to understand diffusion since Vere Gordon Childe's seminal publication The Danube in Prehistory (1929). While early diffusionist arguments have long been viewed as over-simplistic (Rowe Reference Rowe1966), lively debate continues on whether population expansion involves a replacement or merging of peoples (e.g. Renfrew Reference Renfrew1992; Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2015: 53–103), particularly in terms of agriculture and changes in cultural geography (e.g. Rigaud et al. Reference Rigaud, d'Errico and Vanhaeren2015) and human evolution (e.g. Mellars & French Reference Mellars and French2011; Eriksson et al. Reference Eriksson, Betti, Friend, Lycett, Singarayerd, Von Cramon-Taubadel, Valdes, Ballouxe and Manica2012).

Rarely do we have the historical knowledge to explain these changes. We do, however, have that knowledge for Doria Gudaluk. The archaeological evidence shows that during this period of population displacement and accelerated change, Aboriginal people from central Arnhem Land worked in partnership with Jawoyn people from Barunga to preserve important cultural beliefs and practices. The critical point for archaeologists is that, in this instance, population displacement was characterised by cooperation between neighbouring peoples, rather than conflict, in the face of a powerful external force.

Acknowledgements

We thank the traditional owners and custodians, past and present, for permission to research Doria Gudaluk and publish the images in this paper. We are grateful to junggayi (traditional custodian) Nell Brown for permission to publish this paper, and to all of the Aboriginal people who have accompanied us to this site, most recently Rachael Willika, Jeannie Tiati and Troy Friday. We thank Bruno David, Francesca Merlan and June Ross for thoughtful comments on this paper. The site plan is by Jordan Ralph, Robin Koch, Inés Domingo Sanz, Antoinette Hennessy and students of Flinders University. Antoinette Hennessy re-drew Figure 8. Matthew Ebbs located valuable archival information and assisted with digital tracings. Marlene Lee's photograph is published courtesy of herself, her mother, Verona Willika, and aunt, Jasmine Willika. This research was supported by the following research grants: ‘Shared and separate histories: landscapes of memory in the Barunga region’, Australian Research Council Discovery DP0453101, C. Smith, J. Balme and H. Burke; ‘A stylistic sequence for Barunga rock art’, C. Smith, Faculty of Education, Humanities and Law, Flinders University; and HAR2011-25440, I. Domingo Sanz, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. This article was finalised when C. Smith was a Visiting Adjunct Professor with the Faculty of Social and Cultural Studies at Kyushu University, Japan.