The Lovo Massif

Unlike rock art in the Sahara and southern Africa, both of which are extensively documented, rock art in Central Africa remains widely unknown (cf. de Maret Reference de Maret and van Noten1982; Smith Reference Smith1995, Reference Smith1997; Le Quellec Reference Le Quellec2004). Yet rock art was an important part of Kongo culture, and when dated and considered within its cultural context, the images take on new meanings helpful for furthering our understanding of Kongo decorative systems and, more broadly, past societies and traditions in Central Africa.

The Lower Congo possesses one of the richest concentrations of rock art (145 sites) in this area, and although reported in the sixteenth (del Santissimo Sacramento Reference del Santissimo Sacramento1583) and nineteenth centuries (Tuckey & Smith Reference Tuckey and Smith1818), it has never been comprehensively explored. As a result, its age has remained uncertain, but preliminary research has, however, revealed one coherent entity: the Lovo Massif (Heimlich Reference Heimlich2010a, Reference Heimlich2014a). It is located within the westernmost region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, north of the ancient Kongo kingdom, and inhabited by Ndibu, a subgroup of the Kongo (Figure 1). Hundreds of limestone outcrops with carved surfaces, as well as numerous caves and rocky overhangs, rise up over an area of about 430km2. The massif was studied in 1952 by Joseph de Munck (Reference de Munck1960), Paul Raymaekers and Hendrik van Moorsel (Reference Raymaekers and van Moorsel1964), and by Pierre de Maret (Reference de Maret and van Noten1982, Reference de Maret, Blakely, van Beek and Thomson1994). No additional field research was undertaken on the rock art of the Lower Congo until 2007.

Figure 1. Location of the Lovo Massif (modified after Cooksey et al. Reference Cooksey, Poynor and Vanhee2013).

The rock art of Central Africa is distinguished by the importance of painted and engraved non-figurative art. In most cases, the meaning of these images remains unclear despite extensive studies such as those at the site of Bidzar in Cameroon, or the Ogooué Valley in Gabon (Marliac Reference Marliac1981; Oslisly & Peyrot Reference Oslisly and Peyrot1993). Locally at least, however, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has long been known for its rock art sites (cf. Calonne-Beaufaict Reference Calonne-Beaufaict1921; Breuil Reference Breuil1952; Mortelmans Reference Mortelmans1952). In her dissertation on the rock art of Central Africa, Alexandra Loumpet-Galitzine (Reference Loumpet-Galitzine1994) estimated that there were 10000 images across a sample of 92 sites, including 682 figures in the Lovo Massif.

When Portuguese sailors discovered the Kongo kingdom in 1483, they were astonished to discover a centralised political state. At the height of the Kongo hegemony, during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the kingdom controlled land that today belongs to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola and the Republic of the Congo, spanning an area of approximately 130000km2 (Thornton Reference Thornton1983). Following the conversion to Christianity of several kings beginning in the fifteenth century, missionaries, emissaries and traders were able to give a precise description of daily and religious life in the kingdom. As an exceptionally significant cultural landmark for Africans and the African Diaspora, Kongo culture has been among the most prominent of African traditions in the Americas (Arrom & García Arévalo Reference Arrom and García Arévalo1986; Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992; Deagan & MacMahon Reference Deagan and MacMahon1995; Cooksey et al. Reference Cooksey, Poynor and Vanhee2013).

From the end of the fifteenth century, Kongo became one of the best-documented kingdoms of Africa thanks to historical records (Cuvelier & Jadin Reference Cuvelier and Jadin1954; Balandier Reference Balandier1965; Vansina Reference Vansina1965; Thornton Reference Thornton1983; Hilton Reference Hilton1985) and, more recently, ethnographic, anthropological and art historical studies (Laman Reference Laman1953, Reference Laman1957, Reference Laman1962, Reference Laman1968; Van Wing Reference Van Wing1959; Fu-Kiau kia Bunseki-Lumanisa Reference Fu-Kiau Kia Bunseki-Lumanisa1969; Janzen & MacGaffey Reference Janzen and MacGaffey1974; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson and Cornet1981; MacGaffey Reference MacGaffey1986, Reference MacGaffey, Cooksey, Poynor and Vanhee2013; MacGaffey et al. Reference MacGaffey, Harris, Williams and Driskell1993; de Heusch Reference de Heusch2000; Fromont Reference Fromont2014). Nevertheless, it remains underexplored archaeologically (Clist Reference Clist, Lanfranchi and Clist1991; de Maret Reference de Maret and Stahl2005, Reference de Maret and Wotzka2006). For the moment, publications relating to the Early Iron Age, a period that saw the emergence of the Kingdom of Kongo, are rare (Clist Reference Clist2012). Therefore, the chronological framework outlined by Georges Mortelmans, completed later by Pierre de Maret, and today by the KongoKing Research Group, continues to be the basis for the classification of ceramic groups in the Lower Congo (Mortelmans Reference Mortelmans, Monteyne, Mortelmans and Nenquin1962; de Maret Reference de Maret1972, Reference de Maret1986; Clist et al. Reference Clist, Cranshof, de Schryver, Herremans, Karklins, Matonda, Steyaert and Bostoen2015a & Reference Clist, Cranshof, de Schryver, Herremans, Karklins, Matonda, Polet, Sengeløv, Steyaert, Verhaege and Bostoenb). Not until the last six centuries of our era can other groups of Lower Congo ceramics be recognised in association with the Kongo kingdom. Their dispersion could bear witness to the commercial and political entities of the time (de Maret Reference de Maret and Stahl2005).

Between 2007 and 2011, a series of four field studies were conducted with the following research objectives:

-

• To produce the most complete inventory possible of the Lovo Massif rock art.

-

• To determine the sequence of styles and the areas where they are found.

-

• To date the rock art.

-

• To correlate the rock art with the archaeological sequence, determining the relationships between the art and the Kongo kingdom.

-

• To assess the extent to which these sites are still visited today for religious or ceremonial reasons.

-

• To bring the significance of the Lovo Massif rock art to the attention of UNESCO's World Heritage list.

Going beyond iconographic analyses, this research shows that rock art can provide historians with a primary source of evidence, alongside historical records and oral traditions, through integration with historical, anthropological, archaeological and linguistic data (Le Quellec et al. Reference Le Quellec, Fauvelle-Aymar and Bon2009).

New investigations

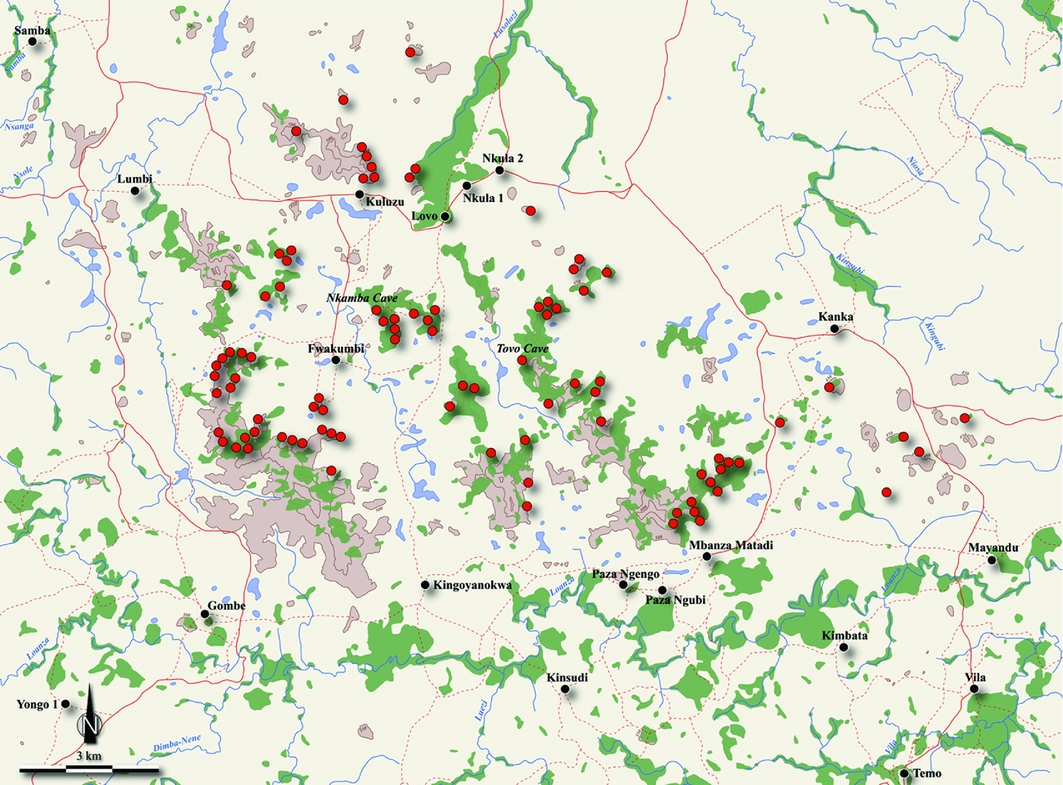

With 102 different sites (including 16 decorated caves) and more than 5000 images, the Lovo Massif is one of the largest known concentrations of rock art in Central Africa. Between 2007 and 2011, 53 of these sites were studied, 43 of which had never before been reported. Around 78 per cent of the Lovo Massif area was surveyed, and images were recorded using digital photography following the method developed by Le Quellec et al. (Reference Le Quellec, Duquesnoy and Defrasne2015). The red circles shown on the map of the region in Figure 2 represent the main outcrops of the Lovo Massif that have been studied (but not outlying ones).

Figure 2. Map of the rock art sites studied in the Lovo Massif. The red circles indicate the rock art sites, while the black circles indicate villages. The sites of Fwakumbi and Ngembo are not shown as they are located in a neighbouring area.

Once the database was completed, the distribution of the rock art could be assessed, something that had not previously been possible. First, the rock images were classified into four groups: A, B, C and D (Figure 3). Group A includes anthropomorphs and therianthropes (mythical beings, part human and part animal) painted in red and armed with rifles or smoking pipes. The cross SI-CR-A4 (Figure 3) was the most frequently recorded motif. Group B essentially consists of engraved motifs. The only anthropomorphic type shows the trunk of a body represented by multiple lines. Lizard-like shapes and the cross SI-CR-B (Figure 3) are the most frequently recorded motifs. In group C, the anthropomorphs, drawn in black, are armed with a sword or a bow. Lizard-like shapes and antelopes are the two most typical zoomorphic types. The cross SI-CR-A1 (Figure 3) is the most frequently found. Group D is characterised by red geometric paintings with fingered prints (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The main image types associated with the four groups of rock art identified in the Lovo Massif area. Groups A, B and C appear to be variants of the same stylistic Kongo tradition, while group D appears more distinct.

Figure 4. Map showing distribution of group D rock art with higher-density areas in red.

Group A seems to have a much more diffuse distribution than groups B and C. Motifs of this group are found north of Mbanza Kongo (Figure 1), the former capital of the Kongo kingdom, as far west as the mouth of the Congo River, and also extend to the south. Groups B and C, in contrast, are restricted to the borders of the former Kongo kingdom.

Schematic paintings of the same type as group D are found in Zambia, Malawi, northern Mozambique, Angola, the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, southern and western Tanzania and the environs of Lake Victoria. This wide distribution of red paintings suggests possible communication networks spanning large areas, and could relate to movements of hunter-gatherer populations, especially the groups known as the Twa (Clark Reference Clark and Summers1959; Phillipson Reference Phillipson1972, Reference Phillipson1976; Smith Reference Smith1995, Reference Smith1997; Namono Reference Namono2010; Zubieta Reference Zubieta Calvert, Gillette, Greer, Hayward and Murray2014). According to the traditions documented in Zambia and Malawi, they inhabited the area prior to the Bantu migrations. If the Pygmies were indeed the descendants of ancient indigenous peoples of Central Africa, this would have important implications for our understanding of how a large part of Africa was eventually populated (Smith Reference Smith and Soodyal2006).

The results also show that there is a clear stylistic and thematic distinction separating the red geometric paintings of group D from those of groups A, B and C. We can, therefore, consider two possibilities. Either these different traditions correspond to two neighbouring ethnic groups, confirming the hypothesis of a hunter-gatherer rock art tradition, or they are associated with specific Kongo rituals (perhaps specifically male or female oriented). New archaeological excavations, direct dating of the paintings and further investigation of oral traditions enable us to test these hypotheses.

Radiocarbon dating the rock art of the Lower Congo

Traditionally, researchers have tried to establish the chronological sequence of rock art styles in the region by observing the styles and overlays (De Munck Reference de Munck1960; Mortelmans & Monteyne Reference Mortelmans, Monteyne, Mortelmans and Nenquin1962; Raymaekers & van Moorsel Reference Raymaekers and van Moorsel1964; de Maret Reference de Maret, Blakely, van Beek and Thomson1994; Martinez-Ruiz Reference Martinez-Ruiz2013). By collaborating with the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, it has been possible to obtain direct dates for charcoal drawings from this region for the first time (Heimlich et al. Reference Heimlich, Richardin, Gandolfo, Laval and Menu2013). Nine direct dates (the quantity was limited by the challenging nature of the work) were obtained from paintings, including eight from Tovo Cave, which is unique in Africa (Figure 5 & Table 1).

Figure 5. Direct radiocarbon dates for the rock art: presentation of probability densities of age (in AD) after calibration in OxCal v4.2 using the SHCal13 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Hua, Blackwell, Niu, Buck, Guilderson, Heaton, Palmer, Reimer, Reimer, Turney and Zimmerman2013).

Table 1. Results of the radiocarbon dating of the pigment samples, with calibrated calendar ages. Dates calibrated in OxCal v4.2 using the SHCal13 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Hua, Blackwell, Niu, Buck, Guilderson, Heaton, Palmer, Reimer, Reimer, Turney and Zimmerman2013).

In Tovo Cave, the initial results (Table 1) indicate dates between 1480 and 1800 cal AD (from SacA 21461–SacA 21463, from SacA 22300–SacA 22303). These results confirm the relationship with Kongo kingdom rituals, although the possibility that left-over materials from earlier occupations of the cave were used cannot be excluded (Valladas Reference Valladas2003; Cuzange et al. Reference Cuzange, Delqué-Kolic, Goslar, Grootes, Higham, Kaltnecker, Nadeau, Oberlin, Paterne, van der Plicht, Ramsey, Valladas, Clottes and Geneste2007; Bonneau et al. Reference Bonneau, Brock, Higham, Pearce and Pollard2011). Two crosses (SacA 22301; SacA22302), whose linesintersect in the middle, are dated to between 1630 and 1800 cal AD, and are similar to many objects of Kongo Christian art from the same period. An indeterminate zoomorphic figure in a small alcove in the first chambers of the cave was dated directly to 1335±45 BP, in other words, between 652 and 859 cal AD (SacA 29125).

In the Nkamba cave, a depiction of a human figure with the left hand on the hip and the right arm raised has been radiocarbon dated to between 1270 and 1620 cal AD (SacA 29137). This gesture appears to be characteristic of Kongo art, also appearing, for example, on the carvedhilt of the prestige swords of the sixteenth century (Fromont Reference Fromont2011a). The pommel, often pierced with two holes, looks like a head, and the guard that protects the hand resembles the arms of a human figure. The date of the Nkamba depiction confirms the importance of this posture as a symbol within Kongo art (Pigafetta & Lopes Reference Pigafetta and Lopes1591; Merolla & Piccardo Reference Merolla and Piccardo1692; de Grandpré Reference de Grandpré1801; L'Hoist Reference L'Hoist1932) potentially as far back as the thirteenth century AD. That is particularly significant given that little is known about the existence of the kingdom of Kongo prior to the arrival of Europeans (Ravenstein Reference Ravenstein1901; Cuvelier Reference Cuvelier1941; Van Wing Reference Van Wing1959; Vansina Reference Vansina1963, Reference Vansina1994; Esteves Reference Esteves1989; Clist Reference Clist, Lanfranchi and Clist1991, Reference Clist2012; Thornton Reference Thornton2001a; de Maret Reference de Maret and Stahl2005, Reference de Maret and Wotzka2006; Bostoen et al. Reference Bostoen, Ndonda Tshiyayi and de Schryver2013; Clist et al. Reference Clist, Cranshof, de Schryver, Herremans, Karklins, Matonda, Steyaert and Bostoen2015a & Reference Clist, Cranshof, de Schryver, Herremans, Karklins, Matonda, Polet, Sengeløv, Steyaert, Verhaege and Bostoenb).

In another cave among the Tovo outcrops, a hearth has been observed with a ceramic of group III placed upside down. Husks of peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) and sweet potato skins (Ipomoea batatas) were also collected inside the hearth. Nearby, a level containing achatines shells (Achatina fulica), of a thickness of 400mm, was observed. A wood utensil (in the form of a double oval-shaped spoon) was also collected. At the bottom of the pottery, a sample was taken on a charred section, allowing the group III ceramics to be radiocarbon dated for the first time. The date was indicated between 1434 and 1618 AD cal AD (SacA 172 29124) (Figure 6). These results suggest that the occupation of the Tovo and Nkamba Caves were contemporaneous with the ancient kingdom, while also allowing correlation between some of the directly dated Tovo motifs and ceramic types with similar decorative patterns.

Figure 6. Ceramic vessel from Tovo Cave (photograph by G. Heimlich).

Rock art and the history of the Kongo kingdom

The results of this research allow rock art traditions to be integrated with Kongo ritual practices, confirming that certain rituals and symbolic aspects of Kongo art are pre-Christian. They also show that the rock art includes examples of a complementary illustration of decorative motifs that are featured ona variety of objects (basketries, textiles, ivory horns, pottery, crucifixes (Figure 7), tombstones, headgear and ornaments), as well as in the signatures of Kongo kings and nobles. Interlaced diamond motifs, grids of diamond or quadrangular shapes and Kongo crosses are recurrent throughout the Kongo kingdom. They are a fundamental feature of Kongo visual syntax over the long term, and are ultimately derived from basketry and weaving (Mortelmans & Monteyne Reference Mortelmans, Monteyne, Mortelmans and Nenquin1962; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson and Cornet1981; Thornton Reference Thornton1998; Bassani & McLeod Reference Bassani and McLeod2000; Fromont Reference Fromont2011b, Reference Fromont2014).

Figure 7. Crucifix from the church of Ngongo Mbata (photograph by G. Heimlich).

The significance of the Kongo cross over time

With a view to interpreting the principal characteristics of Kongo themes, one may consider the function and meaning of the cross symbol (Figure 8). The cross was one of the major symbols of the kimpasi initiation ceremony, much to the annoyance of European missionaries (Cavazzi Reference Cavazzi1687; de Bouveignes & Cuvelier Reference de Bouveignes and Cuvelier1951). Placed in the middle of a shrine and flanked by two anthropomorphic statues (Toso Reference Toso1984), the cross referred to the cyclical passage from death to afterlife. Other markers included strangely shaped stones and twisted, red-coloured roots known to be embodiments of nkita supernatural forces that also playeda principal role in this ceremony (da Caltanisetta & Bontinck Reference da Caltanisetta and Bontinck1970). A deposit of this type was observed in the decorated cave of Nkamba, which may well date back to the sixteenth century. Nowadays, several local Kongo chiefs still relate some of the rock art of the Lovo Massif to kimpasi.

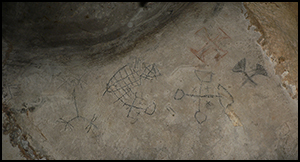

Figure 8. Art within the decorated cave of Ntadi Ntadi, depicting three cruciform Kongo crosses, a lizard-like shape and a gridded pattern (photograph by G. Heimlich).

At the confluence of Kongo and Christian religious thought, the cross was a symbol of equal importance to both religious cultures. It belonged to Christianity, as well as to traditional Kongo religion, in which the use of the cross predates the arrival of Christian missionaries and was probably rooted in an old Kongo symbolic tradition (Fromont Reference Fromont2014). Consequently, it is quite possible, if not probable, that at least some of the rock art of the Lovo Massif was connected to the kimpasi initiation rite (Heimlich Reference Heimlich, Cooksey, Poynor and Vanhee2013a & Reference Heimlich, Cooksey, Poynor and Vanheeb; Heimlich et al. Reference Heimlich, Richardin, Gandolfo, Laval and Menu2013).

A particular link with the world of the afterlife was also highlighted (Thornton Reference Thornton and Heywood2001b). One of the main rituals of the santu institution, with which the Ndimbankondo rock art can be connected, was to make a low bow at the grave of a great deceased hunter to obtain his blessing (Bentley Reference Bentley1900; Weeks Reference Weeks1908, Reference Weeks1909; Olson-Manke Reference Olson-Manke1928; Manker Reference Manker1929). Figure 9 shows this type of cross as seen at Ndimbankondo rock art sites. Ndimbankondo is one of the main outcrops of the Lovo Massif. The Ndimbankondo cruciform motifs are identical to the ‘santu crosses’ (previous scholars having labelled these as ‘Maltese crosses’) used in these rituals (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Tracing of a santu cross at the rock art site of Ndimbankondo I (photograph by G. Heimlich).

Figure 10. Santu cross used in rituals (photograph by J. Van de Vyver, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren © 2016).

Rock art and local mythologies

Another important relationship connects rock art and mythology. All known mythical narratives in Central Africa show a double anthropogony whereby the rock art is believed to have been created by an earlier population of small deformed beings who subsequently disappeared. Different Kongo clans settled on lands of the mafulamengo, mbwidi mbodila and mbaka (Cuvelier Reference Cuvelier1930, Reference Cuvelier1931; Laman Reference Laman1936, Reference Laman1953, Reference Laman1962; Van Wing Reference Van Wing1959; Wannyn Reference Wannyn1961; de Heusch Reference de Heusch1975, Reference de Heusch2000; MacGaffey Reference MacGaffey1986). In the oral traditions collected in the Lovo Massif, however, there is no mention of the mbaka, who are sometimes characterised as dwarves or Pygmies. The mafulamengo were directly associated with ironworking and the prestige and power that specialised knowledge of blacksmithing conferred.

As is often the case with rock art in Africa, the images from the Lovo Massif are considered by current inhabitants of the area to have been the work of legendary peoples, former owners of the land and masters of the elements, who bear no relation to the modern day population (Le Quellec Reference Le Quellec2004).

Among the mafulamengo and mbwidi mbodila, the local simbi spirits were the authors of the rock art of Fwakumbi and Ngembo. Bernard Divangambuta, the local chief of the village of Mbanza Nkula, indicated that 12 simbi water spirits are engraved at Fwakumbi (Heimlich Reference Heimlich2010b, Reference Heimlich2014a), and that his ancestors were not the creators of the rock art. They only made offerings to local spirits named simbi in order to obtain their blessing. The use of the Fwakumbi and Ngembo engravings probably results from a renewed motivation, that is to say, the integration of ancient art with current ritual practices. Whether or not this reading is correct, all these traditions clearly fit the rock art within the ritual universe of local interpreters (Vansina Reference Vansina1982; de Maret Reference de Maret, Blakely, van Beek and Thomson1994; Le Quellec Reference Le Quellec2004).

That much is illustrated by the myth relating to the site of Fwakumbi, which refers to a couple who drowned and subsequently turned into a simbi after transgressing a prohibition. A variant of this same mythical tradition has been recorded in the region of Mbanza Kongo (Martinez-Ruiz Reference Martinez-Ruiz2013). Accordingly, we can conclude that rock art, toponymy (Fwakumbi), the significance of water and a form of worship devoted to simbi are all closely intertwined and of great symbolic importance among Kongo peoples.

Concluding remarks

This study presents results from the first systematic survey of the Lovo Massif rock art. Four groups of motif were identified, three of which (A, B and C) can be considered variants of a single stylistic Kongo tradition. For the first time, direct radiocarbon dates have been obtained forthe motifs that confirm their contemporaneity with rituals of the Kongo kingdom. Nevertheless, a more precise chronological framework is desirable, as it is possible that the origin of the rock art traditions lies at an earlier period, if one of the dates from Tovo cave dates (SacA 29125) can be confirmed.

By exploring perspectives derived from ethnology, history, archaeology and mythology, it has become apparent that rock art was an important part of Kongo culture. This study has integrated rock art with Kongo ritual practices, confirming that certain aspects of Kongo rituals and symbols belong to the pre-Christian period. Even simple designs, such as the cross motif, may become more meaningful if they can be dated and placed in a specific cultural context. The composite symbolism of the cross has been highlighted here because it is an expression of ancient religious syncretism (Fromont Reference Fromont2011b; Thornton Reference Thornton2013). This approach has also allowed some of the rock art to be related to kimpasi or santu initiation rituals. As with historical records and oral traditions, rock art can also provide historians with first-class documentation that offers a glimpse into the African past.

Sadly, however, the Lovo Massif is currently threatened by numerous limestone quarries (Heimlich Reference Heimlich2014a & Reference Heimlich, Favel and Kurhanb). To save this important heritage, the need for protective measures is urgent. In accordance with the long-held wishes of the Congolese authorities, we have proposed a pilot initiative in the Lovo zone to place this rock art on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites to protect these sites for future generations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jean-Loïc Le Quellec and Pierre de Maret for their supervision, and the Institut des Musées Nationaux du Congo for their close collaboration throughout this research. Thanks also go to Clément Mambu Nsangathi, as well as the inhabitants of the Lovo Massif. I am grateful for logistical support from the Compagnie Sucrière of Kwilu Ngongo, and for scholarships granted by the French Institute of South Africa. The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, kindly gave me access to archives and collections, and various colleagues provided thoughtful discussion while undertaking this work. Finally, I would like to thank Michel Menu, Pascale Richardin and Éric Laval from the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France and their colleagues from the Laboratoire de Mesure du Carbone 14.