Discovery

In 1921, John McPherson donated a collection of Mexican artefacts to his alma mater, Marischal College (now part of the University of Aberdeen) in Aberdeen, Scotland (Figure 1). Born in Maryculter, Aberdeenshire, in 1872, McPherson acquired a broad medical training and became a general practitioner in both Halifax, Nova Scotia, and in Salina Cruz, on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca in Mexico. While in Oaxaca, he collected curiosities, including local antiquities, which he eventually sent back to the Anthropological Museum at Marischal College. Amongst his early acquisitions was an Olmec decorated stone axe, or celt, which we describe here and name the ‘Aberdeen Celt’ (Figure 2). Despite its seemingly simple form and imagery, the Aberdeen Celt pertains to some of the most profound aspects of Olmec religion—in particular, the central importance of maize in terms of ground stone celts and the Olmec maize deity during the early development of Mesoamerican civilisation, when widespread food production first began. Along with describing the celt, this study will also discuss its iconographic meaning, including the supernatural identity of the figure and the object that it grasps.

Figure 1. Dr John McPherson in 1928, with some of his Mexican artefact collection (courtesy of the Aberdeen University Museum Archive).

Figure 2. The Aberdeen Celt (photographs courtesy of the Aberdeen University Museum).

Marischal College Museum records (file 146-26) note that the celt was “Collected by Dr. John McPherson 1910 by purchase, reported as found ‘Jalapa, Tehuantepec River, Oaxaca'”. This probably refers to Jalapa del Marqués, approximately 25km north-west of Santo Domingo Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, and about 50km from McPherson's base in Salina Cruz. The accession number is now 8653 in the Aberdeen University Museum collections. The celt is 233mm long and, at its centre, is a maximum of 102mm wide and 41mm thick. It is made from a glassy, quartz feldspar porphyry—a typical central Mexican volcanic rock (Malcolm J. Hole pers. comm.).

Description

Ground and polished, the Aberdeen Celt features an incised Olmec-style figure that rolls slightly over on to the celt's narrow sides (Figure 3). Whereas some carving is deep—especially the horizontal incisions indicating the figure's neck—other carved regions are relatively shallow, including the pair of profile faces appearing on the cheeks of the figure. Remains of shallow incision can also be discerned around areas of deeper carving, including the eyes: these light scratches denote the initial line rendering of the human figure, which were subsequently amplified by deeper grooving. The material used to make these first incisions remains unknown; perhaps it was quartz crystal, which has a Moh hardness <7. The deeper grooves may have been made using a wood stylus and quartz sand slurry as an abrasive (Digby Reference Digby1964: 15–16), or an even harder material such as garnet (Moh <7.5). These incisions were made on an otherwise entirely functional polished hardstone blade, with the top of the figure's head being at the broad cutting edge.

Figure 3. Incised images on the Aberdeen Celt, which is a maximum of 233mm long, 102mm wide and 41mm thick (illustration by Karl Taube, from photographs).

The Aberdeen Celt features aspects of general Olmec iconography that were not identified or discussed for more than half a century after its discovery. The incised decoration on the celt depicts a humanoid figure grasping a vertical object in its hands—a motif discussed below. One of the most prominent features is the downward-turning mouth with a large upper lip framing a set of teeth, which form a point in the centre of the mouth. Although this particular mouth form is virtually omnipresent in the current corpus of Olmec imagery and a hallmark of ‘Olmec style’, the Aberdeen Celt constitutes the first-known genuine example to exhibit many of these features associated with Middle Preclassic Olmec iconography subsequently found through later excavations at La Venta (and unfortunately looting), such as jade celts, masks and other carvings from Río Pesquero, Veracruz. It is highly unlikely that the celt was carved in the early twentieth century by a particularly creative forger acquainted with Olmec symbolic conventions. This mouth form is a basic trait of the Olmec god of maize, who is one of the most common subjects in Olmec art of the Middle Preclassic (or Formative; c. 800–400 BC) period, especially in terms of carved serpentine and jadeite celtiform objects that replicate an ear of corn in both size and colour. Although first documented almost a century ago, the Aberdeen Celt pertains directly to investigations by Taube (Reference Taube1996, Reference Taube, Clarke and Pye2000, Reference Taube2004) in which he highlights a specific aspect of the Olmec maize god, as well as a bound cylindrical object that he identifies as a sacred maize ear fetish. That this item portrays this Olmec god and the purported maize fetish is further support for identification of both deity and attribute.

Comparanda

Dating stylistically to the Middle Preclassic period (800–400 BC), many of the looted jade objects reportedly discovered at Arroyo (or Río) Pesquero, Veracruz (Wendt et al. Reference Wendt, Bernard and Delsescaux2014) are carved and polished to a high standard, but also feature fine-line incision resembling that found on the face of the Aberdeen Celt. Recent archaeological work at Río Pesquero has now established the presence there of finely carved Olmec jades—notably a cylindrical object depicting a maize ear (see Wendt et al. Reference Wendt, Bernard and Delsescaux2014; Pillsbury et al. Reference Pillsbury, Potts and Richter2017: 207, no. 120). Much Arroyo Pesquero imagery—featuring particularly on celts—often pertains to the symbolism of corn and the Olmec maize god (see Taube Reference Taube2004: 105–21), and uses such fine-line incision.

The greenstone ‘Señor de Las Limas’ (Monument 1, Las Limas; Xalapa Museum, Veracruz) figure features four lightly incised masks on the limbs, quite unlike the deeper bas-relief commonly encountered on Middle Preclassic Olmec monumental sculpture. It is possible that although the Las Limas sculpture is a rather large artefact (approximately 550mm high, weighing 60kg), the lightly incised faces were intentionally carved to evoke lapidary traditions usually associated with smaller jade and serpentine objects. Similar incision can be observed on several of the ‘miniature stelae’ jades from Offering 4 at La Venta and on Olmec-style jades discovered at Chacsinkin, Yucatan (see Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959; Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews1986, Reference Andrews1987; Magaloni Kerpel & Filloy Nadal Reference Magaloni Kerpel and Nadal2013). In addition, a recently excavated Olmec-style jade from Ceibal (or Seibal), Guatemala, portrays a serpent head with its facial features delineated with the same light, fine-line incision (see Inomata & Triadan Reference Inomata, Triadan, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2016: fig. 31). Clearly, such incision was also a basic initial step before deeper lines were incised on Olmec-style carvings in hard stone—including those used to delineate the head and body on the Aberdeen Celt. Although only traces of this fine incision delineating the entire figure on the celt remain in areas of deeper carving, it is largely intact on the more detailed and intricate incisions on the cheeks.

The fleshy arms and the proportion of head to body on the Aberdeen Celt suggest that the figure represents a child (see below). The large feet at the thick basal poll of the axe are rendered with short vertical lines. Similar portrayals of feet with vertical toes at the lower edge are found on other Olmec greenstone axe and celtiform carvings. On the jadeite ‘Kunz Axe’ (American Museum of Natural History, New York, first described in 1890), for example, the snarling personage also has diminutive toes indicated by short, vertically incised lines—although in this case at the narrower bit edge of the blade (Figure 4a). An unprovenanced jadeite carving housed at Dumbarton Oaks Museum also portrays this infant deity, with vertical lines to delineate the toes (Taube Reference Taube2004: pl. 14). This is also the case for a large, celtiform figure of serpentine excavated at the Olmec site of La Merced, Veracruz (Figure 4b). The crying face and pudgy features of the La Merced sculpture strongly suggest a baby; this convention for depicting toes vertically at the lower edge probably alludes to the stubby, plump feet of infants lying supine, rather than standing. A celtiform serpentine plaque, reputedly from Oaxaca, portrays another infantile Olmec—in this case with fleshy arms, and toes delineated by short vertical lines along the basal edge. The figure also exhibits a massive head in relation to the body, which is again suggestive of a baby (Figure 4c).

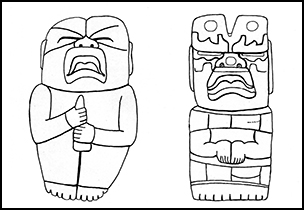

Figure 4. Olmec deities with infant attributes appearing on Olmec-style celtiform carvings: a) The ‘Kunz Axe’, American Museum of Natural History, New York (after Benson & de la Fuente Reference Benson and de la Fuente1996: no. 110); b) Olmec figure, La Merced, Veracruz, Mexico (after Berrin & Fields Reference Berrin and Fields2011: pl. 59); c) portrayal of cleft-headed deity on serpentine celtiform plaque (after Coe Reference Coe and Wauchope1965: fig. 28) (illustrations in Figures 4–7 by Karl Taube, copied from published sources; these lack scales).

The Olmec maize deity

In Olmec imagery, there appear to be several distinct aspects of the maize deity that evoke the growth and development of the maize plant (Taube Reference Taube1996, Reference Taube2004: 90–99). One form is a rotund infant commonly wearing a narrow headband, crenellated ear ornaments that hang vertically from the sides of the face and a crossed band element appearing as beltpiece, pectoral or both. Labelling this being as ‘God IV’, Joralemon (Reference Joralemon1971: 71–76) identified it as the Olmec rain god, based on a previous interpretation by Coe (Reference Coe1968: 111), who had noted a common belief in child or dwarf-like rain spirits—or chaneques—in contemporary Veracruz. Subsequent research based in part on Covarrubias's chart (Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1957: fig. 22) of the evolution of Mesoamerican rain gods, however, suggests that the Olmec rain deity had a snarling feline visage, with deeply furrowed brows and L-shaped eyes turned down at the outer corners. These features are quite unlike the infant being under discussion here, but notably similar to other early Mesoamerican rain gods, including the Zapotec Cocijo, the Maya Chahk and early forms of Tlaloc from central Mexico (Taube Reference Taube and Guthrie1995, Reference Taube2004, Reference Taube2009). Taube (Reference Taube2004: 91–93) argues that rather than the Olmec rain god, the infant deity (Joralemon's (1971) God IV) may correspond to the spirit of seed corn, a concept common in southern Veracruz today—including the Mixe-Popoluca maize child known as Homshuk. As noted below, the facial features and other commonly shared attributes of the infant deity relate directly to the Olmec maize deity, in sharp contrast to the aggressive and mature feline face of their god of rain.

The discovery of the Late Preclassic (200–100 BC) Maya murals at San Bartolo in Guatemala cast entirely new light on early Mesoamerican maize deity imagery (Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Taube and Stuart2005; Taube & Saturno Reference Taube, Saturno, Uriarte and González Lauck2008; Taube et al. Reference Taube, Saturno, Stuart and Hurst2010). In one scene from the West Wall mural, the Maya maize god appears as an infant, cradled in the arms of another being; the Olmec Las Limas figure similarly features an individual holding the supine ‘maize’ infant (see Benson & de la Fuente Reference Benson and de la Fuente1996: 170–71, no. 9). Furthermore, an adjacent scene from the West Wall shows the Maya maize god with a tumpline (forehead sling) and a basket on his back. This is perhaps a reference to the harvesting of corn—a theme also found with an Olmec portrayal of the infant maize god (Guthrie Reference Guthrie1995: 222, no.119). The San Bartolo mural, however, also depicts the maize god within the earth turtle, an important Late Classic Maya mythic theme concerning the resurrection and growth of the maize deity (Taube Reference Taube and Guthrie1995; Taube et al. Reference Taube, Saturno, Stuart and Hurst2010: fig. 46).

A second aspect of the Olmec maize deity seems to embody verdant, growing corn, with a third being the mature maize ear having a cob emerging from the centre of his cleft head (Taube Reference Taube2004: 90–99). As it grows, maize gradually develops from seed to a pliant, growing stalk and, finally, the mature plant featuring maize ears ready for harvest; sharp distinctions between these three aspects of growing corn are lacking. Coe (Reference Coe1968: 111) first identified this third aspect as the Olmec god of corn, noting that the cranial maize element relates to later maize deities of Mesoamerica. All three aspects constitute the same maize deity in stages of growth and development, and have the same basic youthful facial features—almond-shaped eyes turned up at their outer corners and a snarling mouth with a sharply upturned horizontal upper lip. Secondary attributes are also shared between these beings, as will be noted for the Aberdeen Celt.

The earliest-documented images of the Maya maize god—at San Bartolo and Cival in northern Guatemala—have virtually identical features in profile, including the eyes, upturned lip and prominently extended incisors (see Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Taube and Stuart2005; Taube & Saturno Reference Taube, Saturno, Uriarte and González Lauck2008; Taube et al. Reference Taube, Saturno, Stuart and Hurst2010; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2011: 106–108). One example from San Bartolo dates to as early as the fourth century BC, not long after the presumed Olmec demise at La Venta (see Taube & Saturno Reference Taube, Saturno, Uriarte and González Lauck2008: fig. 14b). In contrast to most depictions of the infant embodying fertile maize seed, the other two aspects of the Olmec maize god display prominent, V-shaped clefts in the centre of their brows. Taube (Reference Taube1996: 42) suggested that the cleft alludes to the separating leaves of emerging and budding foliation, and more specifically in terms of maize, the cleft represents the separating bracts, or husk, surrounding an ear of corn. Whereas the Olmec aspect of mature maize has the cob emerging out of the cleft, the embodiment of ‘young’ green corn lacks this central maize ear, as on the Aberdeen Celt, which only displays a simple, V-shaped cranial element—much like a growing immature cob.

During the Middle Preclassic period (c. 800–400 BC), the pair of vertical cheek bands of the green, growing aspect of the Olmec maize god become personified as elongated, inwardly facing heads of the very same cleft-headed deity; this is also seen on the Aberdeen Celt (Figures 3, 5 & 6a–b). These heads are gently curved, which is strongly suggestive of the pliant nature of verdant maize leaves. For two jadeite masks, the cleft is found not only with the two elongated profiles, but also with the main head—although here simply with a small incised line (Figure 5b–c). With the secondary faces on the cheeks, the Aberdeen Celt deity also appears on several stone objects featured in Covarrubias's (Reference Covarrubias1957: fig. 35) Indian art of Mexico and Central America. In this case, the deities are clearly supernatural, with prominent clefts in the brow centre. On one example, a pair of these heads appear above the eyes of an Olmec-style stone yuguito (Figure 6a), while another head occurs above the right eye of an incised Olmec jadeite mask (Figure 6b). For both objects, the incised god heads have enlarged eyes, suggesting not only their supernatural divine status, but also that the heads may be of infants. In the same figure, Covarrubias illustrated a serpentine plaque, housed at the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City, which depicts no less than three examples of the Olmec foliated maize god (Figure 6c). The impression of these multiple heads recalls branching foliation splitting off during growth. Similarly, the long, inward-facing heads of the Olmec deity could be viewed as symmetrical leaves growing from the central axis. While displaying the cleft cranium and facial markings found with the growing aspect of green corn, the Aberdeen Celt also has the plump, fleshy body found with the infant form of the Olmec maize deity—a common combination in Olmec iconography.

Figure 5. Middle Preclassic Olmec portrayals of a cleft-headed deity: a) face-on and profile views of statuette with schematic cleft-headed god on cheeks (from Taube Reference Taube2004: fig. 45b); b) jadeite mask of cleft-headed deity with two more on cheeks, note schematic cleft celt on face, cf. Figure 5c (from Taube Reference Taube2004: fig. 45c); c) jadeite masquette of cleft-headed deity with two more on cheeks, note schematic cleft celt (from Taube Reference Taube2004: fig. 45d) (illustrations by Karl Taube).

Figure 6. Portrayals of Olmec-style cleft-headed deities in Preclassic art: a) Olmec cleft-headed god with profile faces appearing on brow of human face carved on stone yuguito (miniature ball-game ‘yoke’); b) Olmec cleft-headed deity with profile faces appearing on incised jadeite mask; c) Olmec serpentine plaque with multiple images of cleft-headed deity (a–c after Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1957: fig. 35); d) Olmec-style cleft-headed deity, detail of incised vessel from Tlapacoya, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (after Benson & de la Fuente Reference Benson and de la Fuente1996: no. 40); e) vessel fragment bearing incised image of Olmec-style cleft-headed deity, El Mesac, Guatemala (after Clark & Pye Reference Clark, Pye, Clarke and Pye2000: fig. 32) (illustrations by Karl Taube).

All the comparative examples discussed here concerning imagery and symbolism related to the Aberdeen Celt have been from carved stone objects, especially those of serpentine and jadeite. Similar Olmec-style cleft-headed deities, however, also appear on incised vessels from Tlapacoya in the southern Valley of Mexico, as well as from the southern coast of Guatemala (Figure 6d–e). It is notable that these examples are probably earlier than the Aberdeen Celt and date to the late Early Preclassic period—roughly the tenth century BC. Although the ceramic examples could well depict the same being, at present we can say little concerning the immediate origins of the deity appearing on the Aberdeen Celt.

Depicting maize

One of the prominent forms appearing on the Aberdeen Celt is the vertical element tightly held over the figure's central torso (Figures 2–3). A relatively common motif in Olmec art, it usually appears as a vertical bundle of sticks or reeds bound together with horizontal lashing, with a broader, tufted element projecting from the top of the device (Figure 7a). As with the cleft motif, this item has been interpreted in Olmec studies, most commonly being referred to as a ‘torch’ (Cervantes Reference Cervantes1969: 49; see also Taube Reference Taube2004: 80). It has also been identified as a bloodletter (Grove Reference Grove1987; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Edging, Lorenz, Gillespie, Robertson and Fields1991), while Schele (Reference Schele and Guthrie1995: 107) viewed it as representing cuttings for planting. In some cases, an ear of corn projects out of the top of the bundle, which Taube (Reference Taube and Guthrie1995: 89, fig. 8b, 1996: 68–69) identified as feathered maize ear fetishes, such as are known for both ancient and contemporary Puebloan peoples of the American Southwest.

Figure 7. The maize ear fetish in Middle Preclassic Olmec art: a) fragmentary Olmec jadeite ‘clam-shell’ pendant of masked figure grasping maize ear fetish with ‘double-merlon’ and projecting ear of corn, Salitrón Viejo, Honduras (after Hirth & Hirth Reference Hirth, Hirth and Lange1993: fig. 13.13); b) jadeite carving of maize ear fetish with bracts or ‘leaves’ as V-shaped cleft elements, Río Pesquero, Tabasco (after Wendt et al. Reference Wendt, Bernard and Delsescaux2014: fig. 4); c) serpentine carving of maize ear fetish with maize ear projecting out of cleft cranium of Olmec maize god with double-merlon on face (after Benson & de la Fuente Reference Benson and de la Fuente1996: no. 104); d) massive jadeite carving of Olmec maize ear fetish with double-merlon and head of Olmec maize god (from Taube Reference Taube2004: fig. 13) (illustrations by Karl Taube).

As well as two-dimensional images of the maize ear fetish, carvings of this object appear in Middle Preclassic art, including serpentine examples, which portray the head of the mature aspect of the Olmec maize god corresponding to the upper portion where an ear of corn commonly projects from the end of the bundled fetish (Figure 7c). A fragmentary jadeite object in the Peabody Museum at Harvard University originates from a very large depiction of the maize ear fetish (Figure 7d). Collected in 1880 from Campeche in Mexico, this fragment comprises the upper half of a stone maize sceptre featuring the head of the maize god on the central shaft, and the feathered portion above. Although the uppermost portion is broken, it probably had the projecting ear of corn, and it is more than probable that the entire sceptre was over 0.4m in length (Taube Reference Taube2004: 29). The aforementioned jadeite carving of an ear of corn recently discovered at Río Pesquero probably also represents an example of the maize ear fetish; in this case, the ear is enveloped in broad V-shaped elements that correspond to the bracts or ‘leaves’ surrounding an ear of corn (Figure 7b).

The Aberdeen Celt figure holds the maize ear directly on the centre-line of its torso. This convention is found with other Olmec infant sculptures, including the Kunz Axe and the celtiform figure from La Merced (Figure 4a–b). These figures also grasp conical objects, which could be maize, although this is difficult to determine from their schematic nature. In what could be called a ‘double-merlon’, the uppermost portion of the Aberdeen Celt maize bundle—the feather tuft—has two rectangular elements projecting up out of a horizontal band. This motif appears on many elements pertaining to maize, including incised portrayals of celts, maize ear fetishes and, most importantly, the growing face of green corn (Figures 4c, 7a, c–d). On the serpentine plaque depicting the cleft-headed infant maize god, the double-merlon covers the lower half of the face (Figure 4c). Not only is the object carved from green serpentine, but it also portrays an aspect of the corn deity. The body of this being is formed of four vertical bars of bands lashed together by two broad horizontal knots. With the vertical elements, horizontal knots and double-merlon in the upper portion of the sculpture, this plaque could well represent a personified form of the maize ear fetish. For the aforementioned serpentine carving of a maize ear fetish, this motif covers the lower face of the Olmec maize god. The motif also appears on the large jadeite carving of a maize ear fetish in the Peabody Museum at Harvard University (Figure 7c–d).

The four monumental depictions of the Olmec maize god from Teopantecuanitlan, in Guerrero, Mexico, also display the double-merlon facial element and grasp maize ear fetishes in both hands (see Martinez Donjuán Reference Martínez Donjuán, Clark and Arroyo2010: fig. 3.15). The four sculptures project from the east and west rims of a sunken court, which was perhaps ritually flooded through an elaborate drainage system (Taube Reference Taube, Renfrew, Morley and Boyd2018). In profile, these sculptures create the double merlon, perhaps to denote the court as the ‘greening place’. The double-merlon motif may serve as the Olmec sign for ‘green’, which would correspond with not only the face of growing corn, but also its presence on the feathered, upper portion of maize ear fetishes (Taube Reference Taube and Guthrie1995).

Conclusions

The Aberdeen Celt is important because it was discovered, acquired and documented in the first quarter of the twentieth century—well before the Olmec culture and style were recognised by scholars as distinct within the Mesoamerican tradition. It displays many thematic and stylistic conventions known for the Middle Preclassic Olmec, and appears to show an infant with the hallmark Olmec ‘snarl’, denoting its supernatural, divine status. More specifically, it constitutes one of the earliest-known portrayals of a specific aspect of the Olmec maize god holding what has been identified as a maize ear fetish by the second author of this study. Donated to Marischal College in Aberdeen almost a century ago, the celt probably portrays an aspect of the Olmec maize deity only recently identified in the form of green, growing corn, seen in the lightly incised profile heads on the cheeks—an aspect that also occurs on other examples of this god. The item grasped in his hands is a clear example of the so-called ‘torch’, probably a bound corn ear fetish, which is consistent with the probable identity of this being. Although carved from an unusual stone type, and even though we know nothing about its original place of manufacture, the Aberdeen Celt is entirely consistent with the artistic conventions of Middle Preclassic La Venta. Why, though, would artisans not select a piece of their most esteemed stone jadeite—for this highly refined carving? As this variety of quartz porphyry material is not known for carved objects at La Venta, it is possible that the Aberdeen Celt derives from a provincial workshop outside the Olmec heartland, perhaps even in the southern Oaxaca region, where John McPherson acquired it more than a century ago.

Acknowledgements

We thank Melia Knecht, formerly of the Aberdeen University Museum, for assisting N.H. from 2012–2015, and Malcolm Hole of Aberdeen University for mineralogical scrutiny of the Aberdeen Celt. Thanks also go to Francisco Estrada-Belli for the Spanish abstract to be used for social media and to the three anonymous reviewers. Note: author order in this article is alphabetical. Illustrations, reproduced from earlier publications, of objects without a specified provenance are of undocumented origin and sometimes unknown current location; as originally published, they lack linear scales and precise dimensions are not known.