INTRODUCTION

Although many aspects of the archaeology and architectural history of the Palace of Westminster have been comprehensively studied, it still has significant secrets to yield up. One such secret is the concealed door passage at the south-west corner of Westminster Hall, the unveiling of which captured worldwide media attention in February 2020. Sir Lindsay Hoyle, Speaker of the House of Commons, who championed the research findings, said: ‘To think that this walkway has been used by so many important people over the centuries is incredible. I am so proud of our staff for making this discovery and I really hope that this space is celebrated for what it is – a part of our parliamentary history.’Footnote 1

The now hidden doorway and passage were created in 1660–1 as a processional entrance for Charles ii at his coronation, and from 1661 to 1807 served as the main route from Westminster Hall to the House of Commons, then located in the former St Stephen’s Chapel. Walled in since 1851 and forgotten since the mid-twentieth century, the passage was rediscovered in 2018, and consists of a short – and at first sight somewhat unassuming – cavity within the east wall of Westminster Hall, measuring 2.55m deep by 3.45m wide and 3.5m in height. This obscure and forgotten space has offered up a wealth of historical, political, architectural and archaeological evidence about a little understood area of the palace and about the people who frequented it. Here we consider the findings and highlight their significance.

LOCATION AND REDISCOVERY

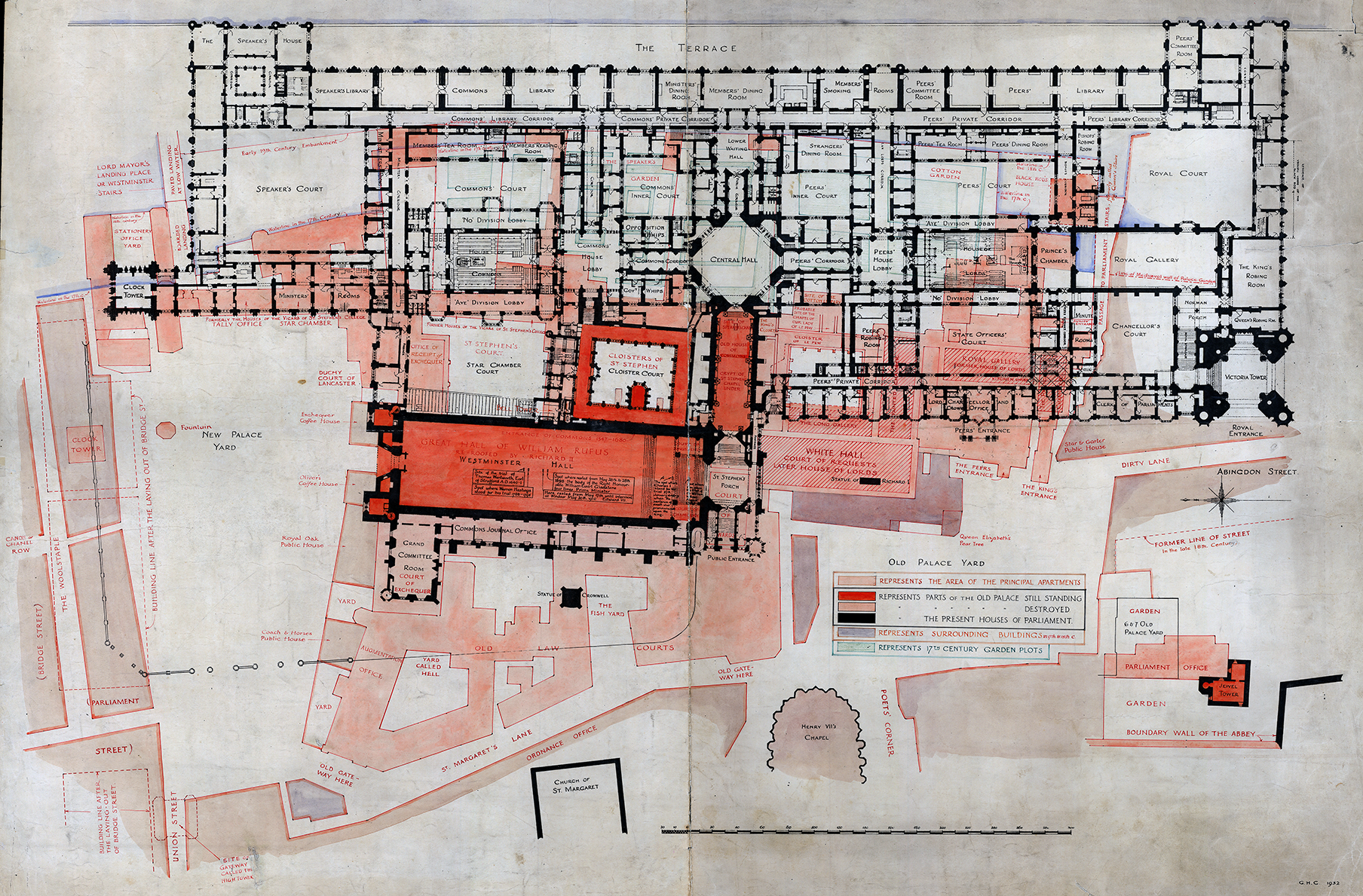

Westminster Hall and parts of St Stephen’s cloister, which mark the two sides of the door passage, are, together with the chapel of St Mary Undercroft, the only buildings from the old Palace of Westminster that, despite much alteration, still remain standing above ground. Although Charles Barry shifted the centre of gravity of his new Palace of Westminster to the east, building out into the River Thames, the medieval survivors were almost as close to his new House of Commons as to the old, and alongside their historical significance they have long been at the centre of political life (fig 1).Footnote 2

Fig 1. Hist Eng, PSA01/08/00003, overlay plan showing the old and new Palaces of Westminster, 1932. The survivors are Westminster Hall, St Stephen’s cloister and St Mary Undercroft, shaded in orange. North is on the left. Image: © Historic England Archives, reproduced with kind permission.

The door passage opened into Westminster Hall in the second bay from the south, near its south-east corner (fig 2). It was cut in 1660–1 through the massive Romanesque east wall of William Rufus’s great hall, completed in 1099, and also through a wedge-shaped thickening on its outside face that had evidently been added when the first stone cloister of St Stephen was built for the royal college of canons based in neighbouring St Stephen’s Chapel, between 1384 and 1396.Footnote 3

Fig 2. Location plan of the doorway (red circle). North is at the top. Drawing: John Crook.

The east side of the door passage is located in the double-height Tudor reconstruction of that earlier cloister. It lies behind panelling, in the second bay from the south in the lower west walk, near the cloister’s south-west corner (fig 3). Probably part funded by King Henry viii (r. 1509–47), this cloister was constructed c 1512–27 at vast expense and may have been intended as a processional way for the king and canons.Footnote 4 After the college was dissolved in 1548, St Stephen’s Chapel passed to the House of Commons as its debating chamber. The cloister was put to work as the service quarters of a great house, occupied by the Auditors of the Exchequer from 1570 to 1794,Footnote 5 although its south-western corner was purloined in 1660 to create the new door passage. From 1794 to 1835 the house was occupied by the Speaker of the House of Commons.

Fig 3. Concealed panel of 1950 providing access to the door passage. Photograph: John Crook.

The existence of a former entrance to the pre-1834 House of Commons in this area was known from a brass plaque on the wall of Westminster Hall, dated 1895 (fig 4). Although the plaque went unnoticed by most parliamentarians and visitors, the lost entrance appeared on historic plans of the old palace and on an important academic reconstruction of the layout of this part of the old palace.Footnote 6 What had been forgotten since the 1950s was that the door passage still lay within the walls of the Hall: it had not been infilled.

Fig 4. The plaque in Westminster Hall. Photograph: John Crook.

The existence of the passage was, however, newly revealed in 2018 through archival research, which led the team to locate and enter it through a hinged access door cut in 1949 through the oak panelling and brick wall behind it in the west range of St Stephen’s cloister (fig 3).Footnote 7 The ability to physically access and record the space, and the unearthing of a wealth of related visual and archival evidence, have now enabled its history and significance to be retold.

DESCRIPTION OF THE DOORWAY AND DOOR PASSAGE

Archival and archaeological evidence for the creation of the door passage

When rediscovered in 2018, the door passage was at first assumed to date from the first part of the seventeenth century.Footnote 8 However, the assignment through dendro-isotope dating of a felling date of Spring 1659 for the timbers of the ceiling joists prompted a major re-assessment.Footnote 9 It was noted that up to 1660 the doorway would have had no obvious purpose since the route from Westminster Hall to the House of Commons and the southern end of the palace was via a medieval doorway nearby. As depicted in a drawing of 1559,Footnote 10 this was in the south wall of Westminster Hall, close to the south-east corner.Footnote 11 It was known to have been blocked off in 1660–1 when the dais at the south end of Westminster Hall was remodelled and extended for Charles ii’s coronation: part of major works in the hall that included repaving the floor.Footnote 12 A new access route to the Commons was therefore needed, and the dimensions of the doorway created for that purpose, as stated in the accounts, matched with those of the door passage.

The new entrance was formed by cutting a tunnel through the east wall of Westminster Hall (fig 5a), a process described in the accounts as ‘beating down’. The key entries in the accounts are:

Masons Imployed in … working of stone for the doorcase at the upper end of Westm[inster] hall cont[aining] Cxxvj foote, cutting [a] way for the s[ai]d doorcase through the stone wall there viij fo[o]t thicke being xj fo[o]t wide and xiiij fo[o]t high and setting the said doorcase w[i]t[h] freestone Cont[aining] Cxxvj fo[o]t and yoting in iron hookes into the same and laying the sell w[i]t[h] vij fo[o]t of Kentish stepp, … letting in an iron cramp to fasten the Kings head over the new doorway, … in Joynting and laying xv foote of Kentish step in two doorwayes at the low[er] end of the hall, in cutting parte of the Collums to enlarge the passage and parte of the wall to give light in the passage going up staires to the parliam[en]t house.Footnote 13

Bricklayers in working up the new doorway in the Hall on both sides and above the lintle Cont[aining] about one rod viij foote of brickworke a bricke and halfe thicke, and working up the wall on one side w[hi]ch was beaten downe to enlarge the coming into the Courte houseFootnote 14 Cont[aining] lxxvij foote of brickworke, in working up the new doorway in the Hall on both sides and above the lintle Cont[aining] about one rod viij foote of brickworke a bricke and halfe thicke, and working up the wall on one side w[hi]ch was beaten downe to enlarge the coming into the Courte house Cont[aining] lxxvij foote of brickworke.Footnote 15

For a greate double stocke locke to the new doores by the house of Com[m]ons staires, 00: 05: 00; … For a greate stay to the doore by the house of Com[m]ons staires wt xjld’ at vd 00: 04: 07.Footnote 16

Fig 5. Development of the opening, showing state in 1661 (a), 1846 (b), 1851 (c), 2021 (d). Drawing: John Crook.

The accounts thus show that an aperture 8ft thick, 11ft wide and 14ft high (2.43 × 3.35 × 4.26m) was made through Westminster Hall’s wall and that its walls were lined with brickwork one and a half bricks thick (about 380mm (15ins)). Because of the fourteenth-century extra skin, the east wall of the hall thickens northwards, but on the centreline measures 2.55m (8ft 5ins). Excluding the brick lining, the opening as broken through would have been about 3.48m (11ft 5ins) in width at the widest, east end. The height from the stone-flagged floor to the ceiling now averages 3.5m (11ft 6ins): it is likely that a taller opening of 4.27m (14ft) high was initially created but subsequently lowered. That would account for the fill visible above the joists, which includes post-medieval brick. The ceiling slopes upwards by around 40mm from east to west.

Exterior of the doorway in Westminster Hall

The only known contemporary illustration of the doorway’s exterior is in Brittannia [sic] Illustrata of 1727 (fig 6), where it is described as the entrance to the House of Commons.Footnote 17 Although this part of the engraving lacks detail, the location and shape of the doorway conform with the archaeological evidence outlined below.

Fig 6. Left: the only identified contemporary image of the doorway, seen at the south end of Westminster Hall, as shown in the rectified detail (right). The central doorway at the south end of Westminster Hall, between the two law courts, is also shown. Image: reproduced from Brittannia Illustrata (BL, RB.23.c.669, 1727, pl 26).

The doorway was blocked off on this side in 1807. That section of Westminster Hall’s east wall was later refaced by Sydney Smirke, probably in 1837, using Huddleston stone from Yorkshire,Footnote 18 and further repairs have taken place subsequently. In the 1850s Charles Barry constructed across the lower part of the doorway a raised platform area leading to the entrance to the chapel of St Mary Undercroft. Although by that time inaccessible, the existence and location of the hidden doorway were still known, and from 1895 it was marked by the brass plaque in Westminster Hall along with bronze studs in the wall, 2.67m apart, to indicate its position (fig 4). In 2014, repairs to the facing of this section of wall revealed part of the doorway’s southern stone jamb along with nineteenth-century brickwork (fig 7).Footnote 19 At that time, however, it was not realised that a void lay behind it.

Fig 7. Left: location of the plaque and the studs; the two pale blocks of Huddleston stone are those that were replaced in 2014. Photograph: John Crook. Right: remains of the right-hand (south) jamb of the stone entrance arch to the passageway as recorded in September 2014 during repairs to the walls. Photograph: © Mark Collins, reproduced with kind permission.

Interior: ceiling

The ceiling of the door passage (fig 8) is formed of oak joists laid flat, running north to south. These are supported on the brick side walls. However, in order to support the medieval walls when the cavity was broken through, the wall must have been needled, and the needle beams would have run east to west. Some larger timbers appear to be visible through gaps in the joists.

Fig 8. The ceiling of the door passage (west at top). Photograph: John Crook.

Interior: the west wall

When constructed in 1660–1 the west side of the door passage encompassed the great doorway leading into and out of Westminster Hall. Four iron pintles – the ‘iron hookes’ in the accountsFootnote 20 – that originally supported the two doors are to be seen on the two sides. The doors closed flush against the face of the square opening, without any rebate. The pintles are set in the stone blocks of the internal corners of the passage. The stone appears to be Kentish Rag, visible where the render has fallen away from the lower block. Removal of small areas of nineteenth-century plaster on this wall revealed the outline of the inner (east) face of the 1661 doorway (fig 9). The door head is flat and is formed of twelve Kentish Rag tapered voussoirs, which continued well above ceiling level.

Fig 9. Elevation of rear wall of passageway. Drawing: John Crook.

This side of the passage was first blocked up in 1807, but a smaller opening with a timber doorcase was inserted in the brickwork in 1846 (figs 5b and 10). That aperture was in turn blocked in 1851 with bricks varying in colour from yellow to salmon pink. Remains of the cut-back red brickwork of 1807 are visible around the edge of the unplastered area. The glass panel on the left covers a pencil graffito of 1851, and there is another dated 1950 to the right.

Fig 10. Rear (west) wall showing the short-lived opening of 1846. It was blocked in 1851, as recorded by a graffito behind the glass panel to its left. Photograph: John Crook.

Interior: the east wall

Any evidence for the original treatment of the opening on the cloister side appears to have been concealed by mid-twentieth-century panelling and the new plaster above it. The cloister pilaster buttresses flanking the opening would originally have acted as jambs, but a lintel must have been set above the opening. From here, the route to the House of Commons continued via the former two-bay porch at the south-west corner of the cloister, from whose first bay a flight of stairs within the thickness of the east wall of Westminster Hall led up to the lobby of St Stephen’s Chapel.Footnote 21 This access arrangement had been formed when the cloister was first built in the late fourteenth century, and was retained when the chapel became the Commons chamber.

The former east end of the door passage is blocked by brickwork of 1851, visible from within the chamber thus formed, including a central pilaster buttress. To the south of that, a patch of yellow brickwork is evidence for the rediscovery of the passageway on 21 June 1949 (fig 11, right). Subsequently a small rectangular opening was formed to the north of the pilaster, to maintain access (fig 17).

Fig 11. Left: north wall. Brickwork of 1660–1 is apparent behind the thin plaster render. Right: south wall. In the adjacent east wall is yellow brick infill of the opening made on 21 June 1949. Photographs: John Crook.

Current state: the north and south walls

The north and south side walls are finished in limewashed hair plaster, 4–6mm thick. On the north side the shadow of the brickwork is discernible behind the render (fig 11, left) and where the plaster has fallen away red bricks are visible set in a very white, soft lime mortar.Footnote 22 On the south wall of the door passage (fig 11, right), the thin plaster render also appears to be primary.

Both walls show evidence of small cavities, later infilled. The one on the north wallFootnote 23 coincides with the end of the door swings when opened and may relate to the ‘greate staye’ of the 1661 accounts, weighing 11lb and evidently of iron, holding back the door.Footnote 24 Its infill of red bricks and hair plaster are, however, earlier than any of the subsequent phases. The position and dimensions of a rectangular patch on the south wallFootnote 25 do not match it and the render appears to be modern cement. Its east edge seems to correspond with the door swing of the south door leaf, so it may be a primary feature related to the actual door. Its depth is not known. Several layers of limewash are discernible on the south wall face; and there are also some scrawled calculations on the latest limewash, and spurious graffiti.Footnote 26

Interior: the floor and sills

The floor of the door passage appears to be of the primary phase of 1661: the plaster render on either side seals the floor slabs, which probably abut the face of the brick skin to north and south. The slabs are of a white limestone, seemingly Purbeck stone from the Portland Formation brought from the Dorset coast,Footnote 27 consistent with the 1660–1 accounts.Footnote 28 The stone for the sills at either end of the new entrance was specified as Kentish Rag (called ‘Kentish Step’ in the accounts).Footnote 29

Analysis of the floor slabs is hindered by spreads of modern mortar, but towards the west end of the door passage the pavers in the centre are worn. Those at the sides, where people would not normally have trodden, retain their tooling, done with a comb chisel and evidently finished in situ.Footnote 30 A part of the pavement appears to have been replaced when the passageway was reopened in 1846, as an area lacking paving stones corresponds in width to that opening.

The floor level inside the chamber is 3.23m aOD. This is consistent to within 30mm with the level of the Purbeck marble paving of 1660–1 in Westminster Hall, as rediscovered by Sydney Smirke in 1835 and at that time thought to be medieval.Footnote 31 The present cloister floor is at 3.40m aOD. Given the insertion of service passages beneath the cloister floors in the nineteenth century, modernised in the twentieth, this is likely to be higher than the original level.

HISTORY AND USES, 1661–1850

The doorway and coronations, 1661–89

Created in 1661–2 as part of the works for the coronation of Charles ii, the doorway served as the main route from Westminster Hall to the House of Commons and also to the south end of the palace. Its use as an access way for coronations is likely to have been short-lived, but its iconographic significance continued for far longer, for the accounts show that a sculpted head of Charles i carved by a William Beard (otherwise unknown) was set above the doorway and secured with an iron cramp.Footnote 32 It was set in a cartouche of Beer stone.Footnote 33

During Charles i’s reign (1625–49), busts of the king had often been placed in prominent places to make a political point, and the Interregnum régime had ordered many of these to be decapitated. The symbolism of the placing of the late king’s head so close to the very spot in Westminster Hall where he had stood trial would therefore not have been lost on contemporaries.Footnote 34 In his History of the Coronation of James II, Lancaster Herald Francis Sandford marks it on a plan as ‘the dore through which the proceeding first entered Westminster Hall’ in 1685. It was thus the way that the king first appeared in splendour in Westminster Hall on the morning of the coronation and walked up to the high table to preside over the coronation breakfast, to the acclamation of the peers.Footnote 35

This use of the doorway for the first ceremonial arrival of the monarch may not have survived for long, given Queen Anne’s infirmities and later remodellings of the southern end of the hall. Nevertheless, the head would still have been highly visible during both the coronation breakfasts and the banquets that followed the crownings. In June–July 1702, not long after Anne’s coronation in April, the cartouche of Charles i was replaced by a bronze cast of a bust of the same king, set upon a pedestal above the doorway.Footnote 36 A fan print depicting the coronation banquet of George ii in 1727 shows it in situ, hovering above the proceedings, emblematic of the longevity and continuity of the monarchy (fig 12).Footnote 37

Fig 12. Fan print of the coronation banquet of George ii, 1727. The bust of Charles i is on the far left. Image: BM, Drawing 1891,0713.376, © The Trustees of the British Museum, reproduced with kind permission.

Route to the House of Commons and to the south end of the Palace of Westminster, 1661–1807

Up to the Restoration the south-west corner of the lower cloister had formed part of the much-prized Auditor of the Exchequer’s house. The sequestration of this area in 1660 by the Office of Works to form the new route to the House of Commons coincided with the reinstatement of former MP Sir Robert Pye to the post of Auditor of the Receipt of the Exchequer. It was a post that he had previously held from 1620 to 1653, but by the time of his return he was evidently incapable and perhaps was unable to resist the purloining of some important circulation space from his official residence.Footnote 38

As the acknowledged entrance to the House of Commons, the doorway and this corner of the cloister would now have been the route taken by the Speaker’s procession through Westminster Hall and into the House, climbing the stairs within the wall of Westminster Hall to reach the Commons Lobby at principal floor level. According to John Hatsell, active as Clerk of the House of Commons from 1768 to 1797, by the 1670s ‘and till long after’ the Speaker ‘always passed through Westminster Hall on his way to the House of Commons, and saluted the courts of Common Pleas and King’s Bench, the judges rising from their seats, with their caps on, to receive and return the Speaker’s salute’.Footnote 39

These two courts, meeting within staging at the south end of the hall that could be dismantled to make way for grand ceremonial events, remained a significant presence here in the eighteenth century. By 1718 a large additional doorway had been pierced through the centre of the south wall of Westminster Hall, accessed between their two courthouses and leading up steps into the Court of Wards and thence into the Commons Lobby,Footnote 40 and the Speaker may well have processed that way thereafter. But although this new central doorway was now the main route from Westminster Hall to the southern end of the palace at the higher (principal) floor level, our doorway was still seen as ‘the enterance of the House of Commons’, as shown by the 1727 Brittannia Illustrata print (fig 6).Footnote 41 And as contemporary plans show, at ground floor level it remained the way to reach the southern end of the palace (eg fig 13).Footnote 42 Its worn pavers are evidence of the high level of the traffic it sustained.

Fig 13. Detail from a plan of 1760–6 showing the doorway and the route leading from it at ground level through St Mary Undercroft (also at that time used by the Burgess Court of the City of Westminster), and then on into Old Palace Yard and the Long Gallery. Plan: Soane Museum SM 37/1/24, © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, reproduced with kind permission.

Westminster Hall witnessed a number of changes over the next few decades: in 1739, the advent of William Kent’s demountable Gothick staging for the two law courts; in 1748–50, a major repair to the roof; and in 1780, the clearing out of the shops and stalls to allow both the raising of the floor level by one foot (305mm) (1780–2) and the refacing of the walls.Footnote 43

As for the bronze bust of Charles i, after several decades of removal for state trials and replacement thereafter,Footnote 44 in 1791 it was finally relocated from what was by this time its ‘obscure corner of Westminster-hall … to a safer and more honourable place’, the passageway from Westminster Hall to Old Palace Yard. This was as part of the works to accommodate the lengthy and complex trial of Warren Hastings (1788–95).Footnote 45 The bust was still regarded as important enough to be featured and illustrated by Thomas Pennant in his popular guidebook to London, where he attributed its design to Bernini.Footnote 46 Contemporary depictions of it, including Pennant’s own, show that it was, rather, after Hubert Le Sueur (fig 14).Footnote 47

Fig 14. Peter Mazell’s engraving of the Le Sueur bust of Charles i. Drawing: Royal Collection Trust RCIN 601957, © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth ii, reproduced with kind permission.

In 1794 the Auditor’s House passed to the Speaker of the House of Commons, thereby reuniting the whole of the west cloister walk under his control.Footnote 48 The stairs leading up to the Commons from the west cloister were soon blocked off,Footnote 49 although the way through our doorway to the southern end of the palace was maintained at ground level until 1807.Footnote 50 This route went past the Le Sueur bust of Charles i, which by 1800 had unfortunately disappeared. Its subsequent fate is unknown.Footnote 51

The doorway from 1807–46

Between 1796 and 1807 James Wyatt repaired and remodelled the Speaker’s House as a grand Gothic Revival palace. As this lavish project drew to its protracted end, in 1807 the doorway was blocked up on the Westminster Hall side.Footnote 52 From that date, red bricks 60/65mm thick in a light grey mortar along with a narrow horizontal lacing timberFootnote 53 are visible inside the passageway. A plan of 1834 shows that the protruding door jambs on the hall side were retained.Footnote 54 The west cloister side, adjacent to a service area, remained open.Footnote 55

In 1819–23 the roof of Westminster Hall, by now in a very decayed state, was repaired by Sir John Soane,Footnote 56 and then in 1834–7 Sir Robert Smirke and his brother and partner Sydney Smirke refaced the walls of the hall with Huddleston stone and lowered the floor again, paving it with York stone.Footnote 57 Smirke’s scaffolding and ladders, and the masons working on his project, played a vital part in saving Westminster Hall from the conflagration that engulfed the old palace on the night of 16 October 1834.Footnote 58

At the southern end of the hall, the Smirkes’s refacing work revealed the blocked side of the doorway once more,Footnote 59 and a short-lived access route to the cloister through it is suggested by a site plan made in c 1835 for the design competition for the new palace.Footnote 60 By 1837 it was closed up again on the hall side, the door jambs and arch now having been hacked back flush with the main wall and the refacing masonry continued over them.Footnote 61

The doorway reopened, 1846–51

Although partly damaged in the fire of 1834, the Speaker’s House, including the west cloister walk, was soon pressed into service as temporary committee rooms, offices, kitchens, dining rooms and storehouses, as all around it Barry’s vast new Palace of Westminster took shape.Footnote 62 The use made of the door passage, then still open, is not recorded; but an 1843 plan for MPs shows it blocked off on the hall side, with no access between the cloister and the hall.Footnote 63

By 1845 a bypass route via the cloister was needed to allow MPs ready access to their entrance in Old Palace Yard, to their temporary chamber and to their facilities at the north end of the site during Barry’s construction of St Stephen’s Entrance and St Stephen’s Hall.Footnote 64 Passing round the perimeter of Westminster Hall,Footnote 65 at first this route started in the medieval porch of St Stephen’s ChapelFootnote 66 next to the south-west corner of the cloister and entered Westminster Hall via a new doorway cut through the wall very near its south end. In 1846, however, evidently needing this area for his works, Barry relocated the route’s starting-point to the north, reopening the blocked door passage by piercing a new aperture about 1.1m wide in the 1807 stone faced brickwork on the hall side (figs 5c, 9–10, 15).Footnote 67

Fig 15. MPs’ pocket plan of 1846 showing the doorway unblocked. Plan: Parliamentary Archives HC/LB/1/114/21, reproduced with kind permission.

That short-lived arrangement marked the final time that the door passage was used as an access route. By 1850 the aperture in its west side was no longer needed. Barry had by now – controversially – topped off his works in this area by demolishing the central window and central section of the Romanesque south wall of Westminster Hall to link it directly by a grand sweeping staircase to his new St Stephen’s Entrance.Footnote 68

THE DOORWAY AND DOOR PASSAGE LOST AND FOUND, 1851–2018

The door passage enclosed on both sides, 1851

In 1850–1 the lower cloister was magnificently and painstakingly restored for Charles Barry by his longstanding lead contractor Thomas Grissell.Footnote 69 Embellished and adorned with Minton tiles and stained glass designed by Pugin,Footnote 70 it was then once more put to use, but this time as a grand circulation and meeting space for MPs, and – to Barry’s great regret – as the members’ cloakroom.Footnote 71

Both sides of the door passage were blocked off as part of these works (figs 5c, 9–10). On the Westminster Hall side, Sydney Smirke’s refacing could now be reinstated over the 1846 aperture. Within the passage, two areas of yellow to pink brickwork from this blocking, on the west and east sides, are contemporaneous. From the same batch,Footnote 72 the bricks were set in a very hard grey cement mortar. The similarity of the jointing indicates that both sides were walled in by the same workman, who may be identified from his pencil inscription on the west wall’s plaster skim (fig 16). This reads:

This room was enclosed

by Tom Porter who was very fond of Ould Ale

The parties who witnessed the articles

of the wall was

R Congdon Mason

J Williams

H Terrey

T Parker

P Duv[a]l

These Masons w[ere]

employed refacing these groines [the vault of the cloister]

August 11th 1851

Real Demorcrats

Fig 16. Graffito of 1851 written by Thomas Porter, bricklayer’s labourer. Photograph: © Adam Watrobski, reproduced with kind permission.

The inscription not only provides a precise date for the enclosure of the space but also names of several of Charles Barry’s workmen, who had evidently used the passage as a place to socialise and talk politics. All of them appear in the 1851 census. Thomas Porter, the ringleader and scribe, was a bricklayer’s labourer living in Water Street near the Strand;Footnote 73 Richard Condon, a stonemason, was domiciled in St MaryleboneFootnote 74 and the other four, also stonemasons, all inhabited Ponsonby Place.Footnote 75

This graffito unlocks a rare and immediate insight into the lives of these workmen. Tom Porter, bricklayer or bricklayer’s labourer, perhaps the product of one of London’s elementary schools, was, in common with around two-thirds of working men at the time, literate.Footnote 76 The group’s self-identification as ‘real demorcrats’ clearly links them with the kind of radical Chartist views that ran strongly within the building trades of London. In 1841–2 the stonemasons working at Westminster had waged a spectacular and highly damaging strike against Barry’s building contractors Grissell and Peto, bringing progress on the palace to a halt, and were militant in pursuing reduced working hours in the next few years.Footnote 77 Bricklayers, and their labourers, whilst notorious for drinking and brawling, were likewise increasingly unionised.Footnote 78

How Tom Porter made his final exit from the door passage is unclear, although some of the brickwork on the eastern side at low level, where not broken through in 1949, appears to have been laid from the outside. Perhaps a temporary hatch was formed there, which was subsequently bricked up once Porter had crawled out. The whole of this new wall was now concealed behind cloakroom furniture for MPs’ coats.

The passage hidden, 1851–1949

A major dynamite explosion, one of the final episodes in the Fenian bombing campaign, which in 1885 greatly damaged the area of Westminster Hall just outside,Footnote 79 may have weakened the structure of the door passage’s ceiling but left its exterior fabric unscathed. A decade later, in December 1895, the brass plaque – described at the time as a tablet – was ceremoniously placed in Westminster Hall by the order of the First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings (fig 4).Footnote 80 Its text indicates the existence of the doorway, dates its creation to 1547, and states that ‘King Charles i passed through this archway, when on 4 January 1641–2, he attempted to arrest in the House of Commons the five members of Parliament. This access to the House of Commons fell into disuse after the year 1680’.

The plaque was one of two erected in Westminster Hall at this time to ‘bring to mind memorable incidents in our national history’,Footnote 81 an initiative arising from the antiquarian zeal of the Clerk of the House, Sir Reginald Douce Palgrave.Footnote 82 Well regarded as a proceduralist, Palgrave’s real passion was history, which he treated in a far more cavalier fashion than he did his official work.Footnote 83 The plaque’s wording, which he supplied, was based on what he confesses in a little-known publication of 1869 to have been the enthusiastic suppositions of a ‘showman’.Footnote 84 Such was the distinction of Palgrave’s office that this text has until very recently commanded evidential credence. Meanwhile, the existence of the passage within the wall of Westminster Hall had perhaps already faded from memory by his time, and by the mid-twentieth century it had certainly been forgotten.

The passage rediscovered and concealed again, 1949–51

In 1940 the southern and eastern ranges of St Stephen’s cloister were damaged beyond repair by a high explosive incendiary bomb, leaving the northern and western sides battered but still standing. A complex and painstaking project to reconstruct the lost parts and to repair the rest was overseen by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott from 1948 to 1951, in tandem with his rebuilding of the bombed Commons chamber. During the installation of air ducts in the west cloister, Scott’s workmen stumbled upon the door passage on 21 June 1949: a considerable surprise to all concerned.Footnote 85 The space was carefully recorded in June and July in photographs and plans.Footnote 86

Any idea of opening up this significant find had no chance of success in the face of pressures to maximise the space available for the MPs’ cloakroom, which was to be reinstated as soon as possible.Footnote 87 Instead, Scott produced a scheme for a concealed access door,Footnote 88 which was implemented during the final stages of the cloister’s restoration. On the cloister side, he arranged for an inconspicuous hinged panel to be cut through his elegant new cloakroom furniture (fig 3). This gave access to the present entrance: yellow bricks,Footnote 89 set in a grey Portland cement mortar, were used both to block the temporary entrance and to construct the present entrance, which was given a concrete lintel (fig 17).

Fig 17. The opening formed in 1950. Photograph: John Crook.

To mark the work, one of Scott’s stonemasons added his own graffito on the northern part of the western wall: ‘1950 Alex Leiper Mason Stonehaven’.Footnote 90 The space was lit using vulcanised rubber electrical wiring and a galvanised metal switch. When rediscovered in 2018 this system sprang immediately into life, activating an Osram lightbulbFootnote 91 manufactured before the death of King George vi in 1952.Footnote 92

The passage forgotten, 1951–2018

In 1951 the west cloister reverted to its earlier use as the MPs’ cloakroom.Footnote 93 The door passage was probably now accessed on an occasional and casual basis, and two nonsensical graffiti scrawls (above) are likely to have been added to its walls between about 1951 and 1967. The latter date was when the west cloister was converted into desk space for backbench Labour MPs.Footnote 94

The electrical supply to the door passage was never cut off, but from about the 1970s any knowledge of the passage or of the existence of the access panel seems once more to have been lost within the parliamentary community at large.Footnote 95 From 1993 the west cloister walk was occupied by Shadow Chancellor Gordon Brown and his team, and finally, from 1997 to 2017, the Parliamentary Labour Party, who most recently placed a sofa in front of the access panel.Footnote 96 Cleared in 2017 for conservation work to begin, the lower cloister is currently unoccupied.

CONCLUSIONS

‘Infinite is the variety of fame and name with which [the doorway] may be coupled’, enthusiastically declared Reginald Douce Palgrave in 1869.Footnote 97 Whilst that does very considerably overstate the case, the rediscovery of this small and rather unglamorous space opens up many insights about the significance, evolution and uses of this now quiet corner of the Palace of Westminster.

The creation of the doorway and door passage in 1660–1 was only one element in a major re-ordering of Westminster Hall for the coronation of Charles ii. The nature and significance of this refurbishment campaign is increasingly being understood.Footnote 98 To that knowledge may now be added the location of this grand new access way. Moreover, the placing of the head of Charles i in such a prominent place over the new doorway may be seen as a highly symbolic gesture that reaffirmed Stuart dynastic legitimacy at the Restoration and at coronations for more than a century beyond that.

The rediscovery of the doorway will also allow a major rethink about the layout of this part of the old palace during the later seventeenth century. This is an era for which relatively little good evidence otherwise survives.

The doorway also assumed an equally significant political role as the principal route to the House of Commons from 1661 to 1794. Its intense level of use is attested by the worn pavers at the centre of the door passage. This was a path trodden for more than a hundred years by leading politicians and statesmen, as well as an access route to the southern end of the palace for people from all walks of life who lived, worked and visited there.

After its first blocking on the hall side in 1807, the door passage made two brief returns to active service, one fleetingly in c 1835, and a second in 1845–50, once more as the way between the cloister and Westminster Hall. The utilisation of the surviving parts of the old palace during Barry’s construction of its huge successor is not yet well understood. His need to redeploy the door passage to create such a circuitous route round his building site provides a rare insight into the scale of the problems that he faced with circulation during some of the most troubled years of this highly complex project.

In its final incarnation as usable space, in 1850–1, the door passage became a mess room for Barry’s workmen who were restoring the cloister, before they walled it in on both sides. The graffiti left by them on the west wall substantiates this use and provides a rare insight into the lives of these skilled and radical craftsmen.

Palgrave’s mounting of the brass plaque on the hall side in 1895 had a minimal impact in keeping the memory of the passage alive. Its low-key treatment after its unexpected rediscovery in 1949 is, moreover, emblematic of the longstanding tensions between the heritage and business uses of the cloister – unsurprisingly, given its proximity to the House of Commons and its value as political space. Hence the doorway and door passage soon returned to near oblivion for many decades. Yet the strong interest and support shown by the Speaker and by many other MPs at the time of their recent rediscovery marks a new and positive chapter in their history and has ensured that this space is now recognised as a worthwhile part of parliament’s history.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The discoveries reported here originated with the St Stephen’s Chapel Project at the University of York, emerging directly from a study supported by York and the Houses of Parliament, and generously part funded by the Leverhulme Trust. We are particularly grateful to Dr Mark Collins FSA for his support and input. We would also like to thank Dr Elizabeth Biggs, Dr John Cooper FSA, Dr Paul Hunneyball, Terry Jardine, Dr Henrik Schoenefeldt and Lady Alexandra Wedgwood FSA, as well as the two anonymous peer reviewers, for their help and advice. The main series of works accounts for the Palace of Westminster (principally TNA E 351, AO 1 and WORK 5) have been transcribed by Simon Neal for the St Stephen’s Chapel Project, and we are grateful to him for giving us access to these.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- aOD

-

above Ordnance Datum

- BL

-

British Library, London

- BM

-

British Museum, London

- Bodleian

-

Bodleian Library, Oxford

- Gentleman’s Mag

-

The Gentleman’s Magazine

- Hist Eng

-

Historic England Archives/National Monuments Record, Swindon

- MoL

-

Museum of London, London

- PA

-

Parliamentary Archives, London

- PoW

-

Palace of Westminster, London

- RCT

-

Royal Collections Trust, London

- SAL

-

Society of Antiquaries of London

- SM

-

Soane Museum, London

- TNA

-

The National Archives, Kew