Exceptional objects are sometimes noted when they are first discovered, but only subsequently reveal their true significance; such was the discovery of a large flint core from West Kennett Farm, near Avebury in Wiltshire. Only belatedly has this flint core been linked to similar, relatively poorly documented, artefacts from Norfolk and Suffolk. Collectively, these enormous objects – worthy of the epithet ‘mega-cores’ – may require revision as cores and the function that they may have served within prehistoric (probably Neolithic) communities. These issues also contribute to consideration of raw material source and the movement of flint across the landscape.

WEST KENNETT FARM

The core was found in March 2009 by Wessex Archaeology during work to collect artefacts from selected fields across the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site before the fields reverted to permanent pasture. This policy was designed to ensure the long-term preservation of archaeological monuments within these fields. West Kennett Farm, centred on NGR SU 10906790, is noted for two, large, palisaded enclosures (National Monument (NM) no. 10380) (fig 1), which were discovered by aerial photography in 1950. Subsequent excavations demonstrated that they were constructed with timber palisades. Grooved Ware pottery, worked flints, animal bone and antler indicated that they were of Late Neolithic date.Footnote 1 The enclosures formed part of a monument complex, which is predominantly located on the floodplain of the River Kennet, but which extends up a tributary coombe to the south. The complex is overlooked on the west by a spur on which a series of, now ploughed-out, round barrows are situated.

Fig 1 West Kennett Farm, showing location of core, known archaeological features and distribution of worked flint (by count and standard deviation from mean). Drawing: Rob Goller

The field survey, which covered 9ha, was based on a hectare grid subdivided into sixteen collection units, 25m apart, and produced 125 pieces of worked flint. Flint density (1.98 pieces per collection unit where flint was recovered) was relatively low, but was comparable with previous surveys in the area and with results from the excavation.Footnote 2 The results might have been confined within grey literature were it not for the recovery of a massive flint flake core, which was found in a hedgerow on the west edge of the field at NGR SU 1085067960.Footnote 3 Apparently, it had been struck heavily by a plough, disturbed from its resting place, collected up as a hazard to ploughing and thrown into the nearest hedge.

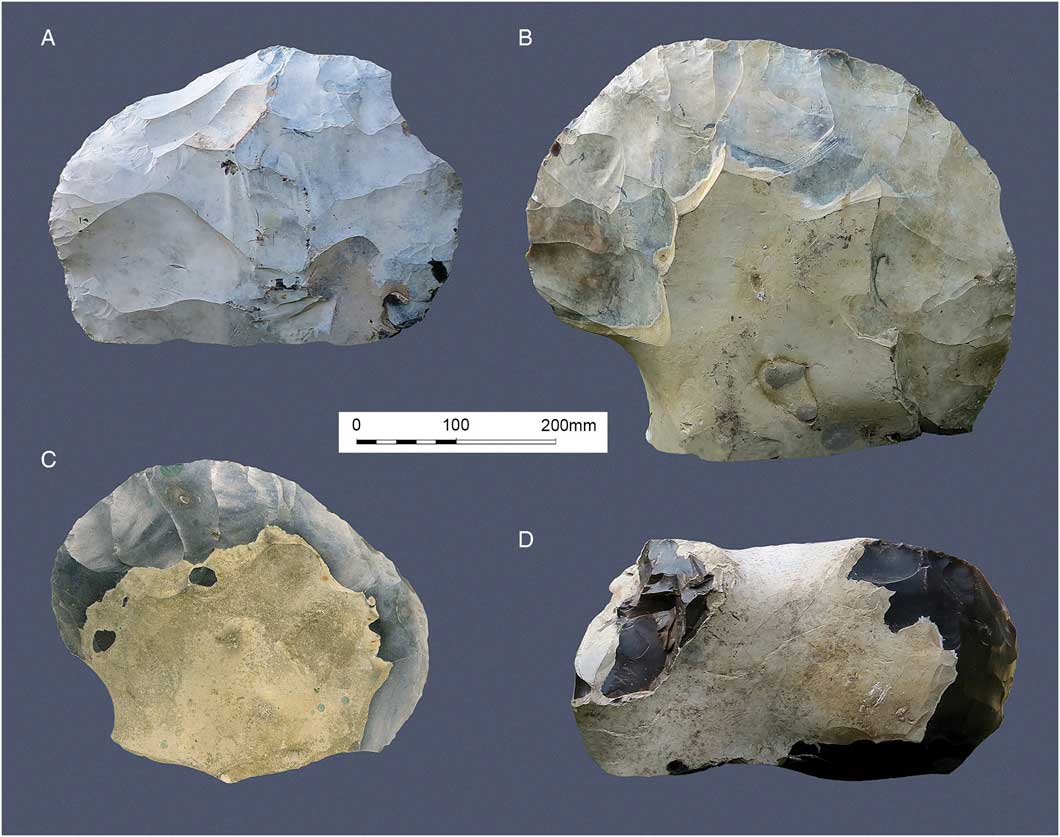

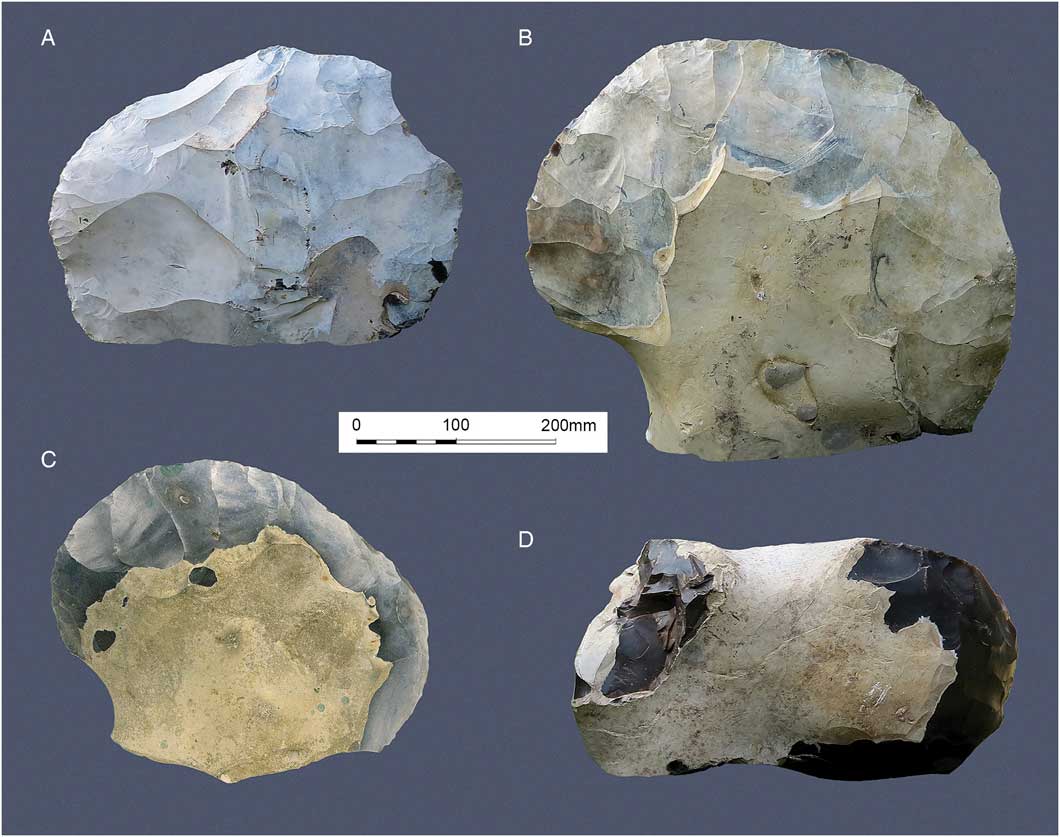

The core (figs 2 and 3A; table 1) is of a type that has been classified under a number of headings (‘segmented choppers’,Footnote 4 ‘tea-cosy’Footnote 5 or ‘keeled’Footnote 6 ), but which remain relatively well known in the Neolithic repertoire of core typology.Footnote 7 The distinctive, slightly sinuous crest (fig 4A) results from the use of alternating flaking, whereby prepared striking platforms alternate with extensively prepared flaking faces using platform abrasion. Platform abrasion removes ‘overhang’ to strengthen the edge of the flaking face and aids precision to the point at which the principal blow will be delivered.

Fig 2 The West Kennett Farm core illustrated in comparison with human scale. Photograph: Wessex Archaeology

Fig 3 Cores (A) West Kennett Farm, (B) Felsham, (C) Cockley Cley and (D) Lakenheath. Photograph: Harding and Lord

Fig 4 Detail of cores from (A) West Kennett Farm, (B) Felsham, (C) Cockley Cley and (D) Lakenheath, showing technology of flaking face and profile (not to scale). Photograph: Harding and Lord

Table 1 Summary metrical attributes of the flint cores

The size of each flake removal, together with negative scar characteristics, suggests that flaking was probably undertaken using a heavy, soft stone hammer. Such controlled flaking of so large an object may have warranted the input from more than one knapper. The ‘base’ is formed by an unmodified flat thermal fracture.

Although the core was found in the hedgerow, the location (fig 1) was close to a small nucleated cluster of worked flints that was focused around the base of the spur on the west side of the field, immediately south of Enclosure 2. This concentration was replicated by a larger cluster on the south side of the spur. It remains unclear whether these concentrations derive from down-slope soil movement from the spur, reflect midden development outside the enclosure or are a combination of both. Nevertheless, the two flake-based concentrations, which formed the background to the location near where the core was found, were of similar composition to the 1,080 pieces from the excavation.Footnote 8 This assemblage, which included a concentration containing scrapers, knives and a ripple-flaked arrowhead in Structure 2 of Enclosure 2, compared favourably with many Late Neolithic Grooved Ware assemblages, although Whittle acknowledged that other periods might also be represented. Cores were small and had been carefully worked down from two or more well-prepared striking platforms. They were made from small nodulesFootnote 9 that probably originated from the Marlborough Downs, with supplementary use of poor quality flint from the floodplain. As such, they contrasted completely with the new discovery.

THE EAST ANGLIAN CORES

Currently, three cores (fig 3B–D; table 1) of a similar type and technology to that from West Kennett Farm are known from various parts of East Anglia, but within a range only 50km apart and largely within the area of the Breckland. None of the locations apparently coincide with known Neolithic monuments. The cores remain unpublished apart from short notes in relevant county journalsFootnote 10 and as entries in county Historic Environment Record files.

-

1 Felsham, in Suffolk (TL 948573) (SHER FHM 010): This core (figs 3B and 4B) remains the largest yet found and was describedFootnote 11 as a ‘very large Neolithic fan-shaped core, weighing over 35lbs with numerous flake scars on both surfaces for two-thirds of the circumference. Found 2 feet deep lying on clay’. The core now resides with the Suffolk Museum Service at West Stow.

-

2 Cockley Cley, in Norfolk (TF 81280606) (NHER 24540): The core (figs 3C and 4C), which is also ‘fan-shaped’, was found in or before 1988 by a farmer in a field. Subsequent survey within the field produced an assemblage of Neolithic, worked flints. The core is retained at Swaffham Museum, in Norfolk.

-

3 Lakenheath, in Suffolk (TL 71388445) (SHER LKH 136): This core (figs 3D and 4D) was found at Grime Fen and is described in the Suffolk Historic Environment Record as a ‘Large flint roughly “fan shaped” core with large, broad flakes removed. Black flint with dark brown patches. Length c. 420 mms, height c. 240 mms, thickness 160 mms. Only a few major flakes removed, circa 4 from the side with approximately 40 per cent cortex remaining and circa 11 from the side with approximately 70 per cent cortex remaining. Similar, although not as fine an example from Felsham.’

The Suffolk Historic Environment Record provides no current location for the core. However, the description is sufficiently similar in appearance and dimensions to a core (now in the possession of John Lord) that was also found at Grime Fen. It was given to the present owner by the farmer who had been using it as a door-stop! The core is less obviously ‘fan-shaped’ than the others, a fact that may, to some extent, relate to incipient thermal fractures in the nodule. However, in all other respects, notably technology and nodule size, it is consistent and merits inclusion with the other examples.

These East Anglian cores were all examined individually by the late Dr John Wymer FSA. He noted their large size and considered them to be prepared, Upper Palaeolithic, crested blade cores. However, they have never been assessed collectively.

CONDITION

The cores from West Kennett Farm, Felsham and Cockley Cley are all covered by a blue surface patina to varying degrees. This is often differentially darker on one side than the other, which may indicate which way up the cores survived in the ploughsoil. ‘Chatter marks’ (conjoining, linear incipient cones of percussion) are noticeable on the examples from West Kennett Farm, Lakenheath and Cockley Cley, especially on the flake arêtes, damage which can be attributed to modern ploughing. Most significantly, the surface condition of the core from West Kennett Farm is directly comparable to both the artefacts from the field-walking and material from excavations across the interior of the Late Neolithic enclosures.Footnote 12 The Lakenheath core, in contrast, is totally unpatinated, but is characterised by a brown surface stain.

GEOLOGY

The cores are all made from large, semi-tabular nodules of consistently good quality flint, which lies beneath a thin chalky cortex up to 8mm thick. Recent flake removals caused by plough impact on the patinated cores from West Kennett Farm, Felsham and Cockley Cley show that the flint is black, grading to mottled grey material. Cherty inclusions are generally absent and structural flaws are restricted to a number of superficial thermal fractures. The Lakenheath core is also of black flint that is apparently of good quality, but is marred by incipient thermal fractures that would have undoubtedly been recognised as potential defects in the nodule by prehistoric knappers.

Flint cannot be sourced chemically. However, the consistent size of the nodules, the very black, homogeneous interior and the relatively thin cortex are sufficiently distinctive to suggest that these flints are likely to be from the Turonian Stage of the Chalk formation (R. Mortimore, pers comm, April 2016). This stage marks the traditional base of the Upper Chalk and can be traced intermittently from Kent to Norfolk, where it includes the Brandon Flint Series, in seams containing flints of ‘unusually large size’Footnote 13 and of a type that prevails in many parts of the Breckland.Footnote 14

DISCUSSION

The cores discussed here have drawn gasps of wonderment from virtually everyone seeing them for the first time, principally for their size. This instinctive response and sense of awe in all probability mirror the feelings of people in prehistory who saw them for the first time in their unpatinated form; cores of this size simply do not occur with any frequency in Britain. Taken together, they may represent some of the largest, systematically worked flint artefacts from prehistoric Britain. Continental parallels can be made, primarily at raw material sources, as at Le Grand-Pressigny, in France, where cores were prepared in the production of blades up to 400mm long.Footnote 15

The cores are all undoubtedly prehistoric as the developed patination and technology make clear, although none was found in a securely dated context. Additional uncanny similarities in the form and raw material (fig 4) raises the possibility that they were derived from the same area, perhaps from a single workshop. Some of the examples from East Anglia were initially described as Neolithic, but were subsequently reassigned to the Upper Palaeolithic on the apparent use of cresting as a means of blade core preparation. There seems little to substantiate this revision. The suggested features of cresting can rarely be linked directly to the implied striking platforms, which is a fundamental relationship in the preparation of blade cores. The markedly convex curvature of the ‘crest’ is arguably detrimental to the production of blades with straight profiles. None of the striking platforms shows any deliberate preparation, but is represented by unmodified thermal surfaces. In contrast, the technology, featuring alternating flaking, contains attributes that can be referenced in many Neolithic industries. In addition, worked flints of Neolithic type were found at both Cockley Cley and West Kennett Farm, the latter a documented Late Neolithic ceremonial monument of national significance.

The appreciation and visual splendour of each piece in this relatively small collection is increased by the quality of the technology and raw material. Care and attention to the preparation and abrasion of striking platforms are techniques of acknowledged core control and management. Perversely, in their current state, they represent little more than prepared core ‘blanks’. The mean length of the negative flake scars (table 1) exceeds that of most Neolithic implements by a considerable margin, although large flakes are, in consequence of the presence of large nodules, more prevalent in the Breckland than in many parts of Britain.Footnote 16 It is arguable that the removals provided blanks for large knives, including those of discoidal form. These distinctive implements featured extensively in the tool repertoire at Grimes Graves,Footnote 17 and have been considered to represent prestige items.Footnote 18 In contrast, the limited number of flake removals (table 1) and surviving cortical cover suggest that none of these cores ever witnessed large-scale flake production.

These arguments suggest that it may be appropriate to redefine the objects less as cores, from which tool blanks were struck, than as objects in their own right, possibly free standing, to be displayed, or incorporated, possibly within a ritual/ceremonial role. The flat ‘base’ in this scenario may have formed an integral part of the creation. Elevating the object may also have emphasised the fan-shaped profile, in much the same way that the convex outlines of many prehistoric monuments are enhanced, notably at West Kennett Farm where the skyline to the west is dominated by the profile of Silbury Hill. This ritual/ceremonial aspect is totally compatible with that ascribed to the palisaded enclosures at West Kennett Farm,Footnote 19 based on their henge-like character and close proximity to water. Furthermore, it reiterates the role that flint may have played in the Neolithic period beyond being merely a means to create stone tools to one possessing non-practical properties.

The source of the nodules remains a primary consideration and is especially pertinent with reference to the core from West Kennett Farm. Flint with the observed characteristics is most likely to have originated from one of the beds of large Turonian flints at the base of the Upper Chalk (R. Mortimore, pers comm, April 2016). These beds are all occluded and the flint absent in the condensed Chalk Rock sections of the Avebury area and the Berkshire Downs.Footnote 20 The bands of very large Turonian flints are also missing, due to similar condensation of the sediment beds, along the north side of Salisbury Plain – for example, Beggars Knoll, near Westbury, in Wiltshire. Further afield, Turonian flints, with occasional large nodules below the Chalk Rock, occur at Fognam Farm Chalk Pit in the Lambourn Valley, north west of Hungerford.Footnote 21 These observations indicate that if the core from West Kennett Farm is a Turonian flint, it must have been brought in from further east, probably from the North or South Downs or East Anglia (R. Mortimore, pers comm, April 2016).

Attempts have been made to study the chemistry of flint to identify the possible source of artefacts,Footnote 22 although thus far none of these techniques has proved to be reliable. Cores of the type and size under discussion make it possible to include archaeological factors into the argument. The occurrence of three such large cores in East Anglia, where Turonian Beds are present, seems more than mere coincidence. It is impossible to confirm whether these prehistoric cores were manufactured from flint obtained directly from the chalk or as nodules from gravel deposits. High quality complete and partial large nodules of this type have been observed in gravel deposits at three locations: Ingham and Flixton, in Suffolk (both near Felsham and Cockley Cley), and further east at Cranwich, in Norfolk. One of the authors (JL) has observed that some of these large nodules contained sonic qualities and were affectionately known by quarry workers as ‘ringers’. The nodules emitted a long, sustained bell-like sound when they were tapped only very lightly. These ‘ringers’ were not only resonant, but revealed the highest quality black flint sporting little, or often no, faults. They stood out from everything else in the gravels when they were detected and were probably equally as attractive to prehistoric craftsmen, sound being a vital sense to all flint-knappers. Attempts to test the resonance of the core from West Kennett Farm were disappointing, although observers did agree that a high frequency emission was produced by only a slight impact with a stone hammer.

It remains impossible to be certain that the West Kennett Farm core also originated from East Anglia, although the similarities in technology and flint quality provide a strong argument that it did. Exactly when it might have been introduced remains more problematic. The Avebury and West Kennett area remains one with deep religious connections and it may have been introduced by latter-day druids; however, the palisaded enclosures remained poorly studied until the 1970s, with no surface earthworks, while the distance from the nearest public road makes ‘fly-tipping’ an improbable option. The surface condition of the core and spatial relationships to other artefact clusters in the enclosures strengthen the view that it does represent an ‘exotic’ introduction that may have arrived in prehistory via the Chalk Ridgeway from East Anglia to Wiltshire, a distance of approximately 220km. Reciprocal movement of artefacts from west to east can be demonstrated by reference to axes, which were moved along the southern seaboard from Cornwall to East Anglia.Footnote 23 This trade of highly valued items included an example that was recovered from a gallery within Greenwell’s Pit at Grimes Graves.Footnote 24

The pattern whereby items of ‘exotic’ raw materials were moved for considerable distances across the prehistoric landscape is well established and can be demonstrated by further reference to polished stone tools. Jadeitite axes from the Alps were transported widely across Central Europe, reaching to the Atlantic coastline and beyond to northern Scotland and Ireland.Footnote 25 Similarly, specific types of flint have been linked with impressive distribution patterns within the Neolithic period. Bostyn classified Early Neolithic raw material movement within the Paris Basin into local (within a radius of 5km from the source), regional (5−50km radius) and exotic (over 50km).Footnote 26 Di Lernia adopted a similar approach for raw materials in south-east Italy, categorising movement into local (within a range of 50km), middle (approximately 50−100km) and long (where export exceeded 250km).Footnote 27 Blades from Le Grand-Pressigny, in France, have been recorded in the Netherlands.Footnote 28 These trends can be replicated across the British Isles where trade and exchange of stone tools are well known.Footnote 29 Exploitation of distinctive flint types that mirror movement across Europe can also be detected. Axes manufactured from distinctly coloured flint alien to East Anglia have been recorded from that area,Footnote 30 which is otherwise traditionally credited with containing some of the finest flint in Britain. Similarly, imported flint, including distinctively coloured material from East Yorkshire, has been documented from the Thornborough henges, where naturally occurring flint is scarce.Footnote 31

Introduction of distinctive flint can also be traced within the Stonehenge and Avebury regions. These include not only flint flakes, some of exceptionally fine quality raw material from both the palisaded enclosures at West Kennett FarmFootnote 32 and from the Marden henge in the Vale of Pewsey, Wiltshire (J. Leary, pers comm, March 2016), but also artefacts of Bullhead flint that were recorded at the West Kennet Avenue.Footnote 33 This distinctive flint, stained green by exposure to glauconitic sand,Footnote 34 occurs in the Reading Beds of south Wiltshire, Hampshire and Dorset or along the River Kennet valley near Reading, 80km to the east. The pattern can be extended to include other silicates, including Portland chert, which reached the Stonehenge environsFootnote 35 from the coast at Portland or inland from the Tisbury area, 15km to the south west of Stonehenge. Greensand chert, introduced from the south west, has similarly been recovered 60km from its most likely source in the Vale of Wardour (R. Mortimore, pers comm, April 2016), as tools and utilised pieces in north Wiltshire at the West Kennet Avenue.Footnote 36

Many of these objects were relatively small and easily transported, but the process nevertheless demonstrates movement over extreme distances. Such movement undoubtedly required a complex network of communication and exchange within a well-ordered community structure to function successfully. Edmonds has argued that these conditions were present within the mid-third millennium bc when finely crafted flint and stone artefacts were transported across Britain.Footnote 37 Such movement of objects and raw material may be seen as a natural response to population movements,Footnote 38 which are now an accepted feature of Neolithic society, possibly occurring as seasonal migration towards ritual sites or as a conscious act of introduction. As a result, these objects, acknowledged for their source, power, texture or colour, were probably held in high esteem, changing ownership through trade, gift or exchange. Such value is especially notable in areas where flint does not occur naturally. Saville has described a core, weighing 750g and thought possibly to be of mined flint that was clearly large enough for blank production but was deposited as a grave gift within the long cairn at Hazleton North, in Gloucestershire.Footnote 39

Despite the suggested link of the West Kennett Farm core to East Anglia, there remains insufficient evidence to link it, or, indeed, any of these cores, directly with flint mining at Grimes Graves. Nevertheless, the apparent production of these cores and their conjectured association with the Late Neolithic period in East Anglia is not coincidental. Increased quantities of Late Neolithic material have been noted repeatedly from the area.Footnote 40 Furthermore, these authors have also noted the presence of ‘heavy’ core tools, which were produced using bifacial flaking, a technology which these cores exemplify to the greatest extent. West Kennett Farm and Grimes Graves both produced Grooved Ware pottery, suggesting broad contemporaneity. No radiocarbon determinations have been calculated for any of the East Anglian cores. However, a tentative chronological relationship can be constructed between the sites at West Kennett Farm, in Wiltshire, and Grimes Graves, in Norfolk. Results from the former cautiously suggest a construction date for the timber enclosures of 2340−2130 cal bc (95 per cent probability),Footnote 41 while current calculations for Grimes Graves suggest that mining of the galleried pits ceased at approximately 2435−2360 cal bc (95 per cent probability).Footnote 42

The lack of failed cores of such immense size from Grimes Graves strengthens the likelihood that they were not from the mines,Footnote 43 although the technology employed, if not the execution, would have been familiar to resident flint workers, many of whom may have themselves been regarded as specialists.Footnote 44 Indeed, attempts to provide any convincing markets for products from Grimes Graves have proved largely unsuccessful. Healy, studying assemblages from Fenland sites, which were all relatively close to the Grimes Graves flint mine site, concluded that only small numbers of flint nodules from a chalk source had been introduced to the Fens.Footnote 45 She regarded this as a response to peat growth, a process that had masked access to local sources. She detected only limited evidence – principally flakes and retouched pieces – to indicate that mined floorstone was present.

Healy lamented that so much effort was apparently expended to extract flint from which very little evidence could be found as finished items, but considered that production may have centred on finished, high quality ‘prestige’ items. Topping elaborated on this theme, stressing not merely the ‘prestige’ of the objects, but also the status of the site, which may have necessitated rituals to accompany extraction.Footnote 46 The associated status afforded to artefacts from these individual sources or regions, including axesFootnote 47 and discoidal knives,Footnote 48 and to those who possessed or viewed them, may extend to cores of the type noted here.

The apparent difficulty with which clearly defined products from Grimes Graves can be identified contrasts with the probable expenditure of labour required to undertake production. Bishop has discussed not only the role of Grimes Graves in isolation, but also within the broader environs.Footnote 49 The study concluded that the area constituted not merely a site, but a ‘source area’ for flint.Footnote 50 It remains impossible to establish unequivocally that these cores were manufactured within the immediate environs of Grimes Graves. Nevertheless, many of the social influences operating at the mine site may also have influenced workshops producing the cores. Bishop argued that flint-working was only possible on this scale when sustained by complex, vibrant social interaction and planning involving large numbers of people.

The symbolic threads, including any possible aesthetic, magical or medicinal properties the stone may have held,Footnote 51 may have provided sufficient incentive to transport such a large piece of high grade or exotic raw material to Wiltshire and, following its arrival, to curate it for future generations. It is conceivable that any symbolism associated with the flint source, which remains undetectable to modern science, was embedded in Neolithic ancestral traditions and folklore. Links to and knowledge of the source may have been of immense significance; the discovery, ownership and ‘cutting’ of such a gem may also have carried considerable status and prestige, work entrusted to a competent, specialist knapper. Possession of such an object, as a personal or communal item, may well have provided status or value to the owner/viewer beyond acceptance of its physical appearance.

The use of stone in the Neolithic period has been adopted as a symbolic reference point with monuments of the dead,Footnote 52 contrasting with monuments of timber that reflect symbols of life. In this respect, the core from West Kennett Farm may seem out of place within a timber monument, although its life-giving use as a source for stone tools cannot be overlooked. Stone was a vital component of monument construction in all parts of Britain where it was available, most notably northern and western regions; in lowland areas, sarsen sufficed. Healy et al noted that the weak local tradition of constructing large communal monuments in East Anglia may have been compensated by ‘symbolically-charged practice (in flint), conducted by skilled specialists, an equivalent to the great Neolithic monuments of some other regions’, which were being constructed at the same time and which also necessitated an abundant labour force.Footnote 53

If cores/objects of this type served more than merely providing blanks for retouched tools and were objects in their own right, it is perhaps surprising that so few of these large pieces have been found, especially as they may have been made to a standard pattern. Just as this small collection has remained in isolation, others may wait to be added to the tally. It is also possible that the value of the raw material was not lost on prospective flint workers in the Bronze Age, who noted the quality of the raw material and utilised blocks for tool manufacture in much the same way that broken stone and flint axes were recycled.

This small study was initiated to document the discovery of a single anomalous object from a ceremonial Neolithic complex at West Kennett Farm, Wiltshire. The thread expanded to consider that its presence at the site may have been something more than coincidental; that it may have represented an object of ceremonial function with strong links through flint to similar artefacts, traditions and communities in East Anglia. These findings and conclusions cannot in themselves determine the final outcome of any argument relating to this discussion. Nevertheless, they open up new avenues of information with which to fuel the debate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was compiled from fieldwork undertaken by Wessex Archaeology. Access to the cores from Felsham and Cockley Cley was provided respectively by Alex McWhirter, Heritage Officer for West Suffolk Council, and Sue Gatuso, Manager of Swaffham Museum, to whom thanks are extended. Thanks are also offered to Professor Rory Mortimore for sharing his knowledge on the geology of flint and chert. Illustrations were prepared by Rob Goller using photographs by Phil Harding and John Lord, and the text was organised by Pippa Bradley FSA at Wessex Archaeology. Inevitably, thanks must finally be extended to the two anonymous academic referees for their comments and improvements to the text.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- BGS

-

British Geological Survey

- CBA

-

Council for British Archaeology

- HBMCE

-

Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England

- HMSO

-

Her Majesty’s Stationary Office

- NGR

-

National Grid Reference