INTRODUCTION

Over the last thirty-five years a number of particularly eye-catching elaborately decorated examples of late medieval jewellery have been discovered in Britain by metal detectorists, including the Middleham jewel and ring (found in 1985),Footnote 1 the Winteringham Tau Cross pendant (found before 1990)Footnote 2 and the Kilgetty pendant (found in 2007).Footnote 3 On 14 November 1998 a massive gold signet ring was found by metal detecting in the parish of Raglan, Monmouthshire (Gwent), by Mr R Treadgold, and reported to the author at Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales (AC-NMW Treasure Case 1998.08). The findspot lay beyond the eastern edge of the village of Raglan, Monmouthshire, in a field of pasture about 210m to the east of St Cadoc’s parish church and about 530m south of Raglan Castle (figs 1–2).Footnote 4 The ring was found some 15m from a veteran oak tree, at a depth of about 50mm, and no other medieval finds were reported from its vicinity. Declared to be treasure under the Treasure Act 1996 by H M Coroner for Gwent on 21 January 1999, the Raglan ring now forms an important example of late medieval goldsmiths’ work within a publicly accessible museum collection, having been acquired by Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales.Footnote 5 This paper considers its stylistic affinities, the circumstantial evidence for ownership and its wider context in light of other signet rings from Wales.

Fig 1. The findspot of the Raglan ring in relation to the late fifteenth-century phase at Raglan Castle and St Cadoc’s church in the modest town, which did not expand when the new castle was built. Fishponds and Upper and Lower Park boundaries from Laurence Smythe’s 1652 map may reflect the late medieval park and ponds. Image: reproduced with permission © NMW.

Fig 2. Aerofilm view looking south of Raglan Castle towards the findspot and town, taken on 14 August 1948. The findspot is indicated, close to a large oak tree. Image: reproduced with permission © Crown: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales: C888430.

DESCRIPTION

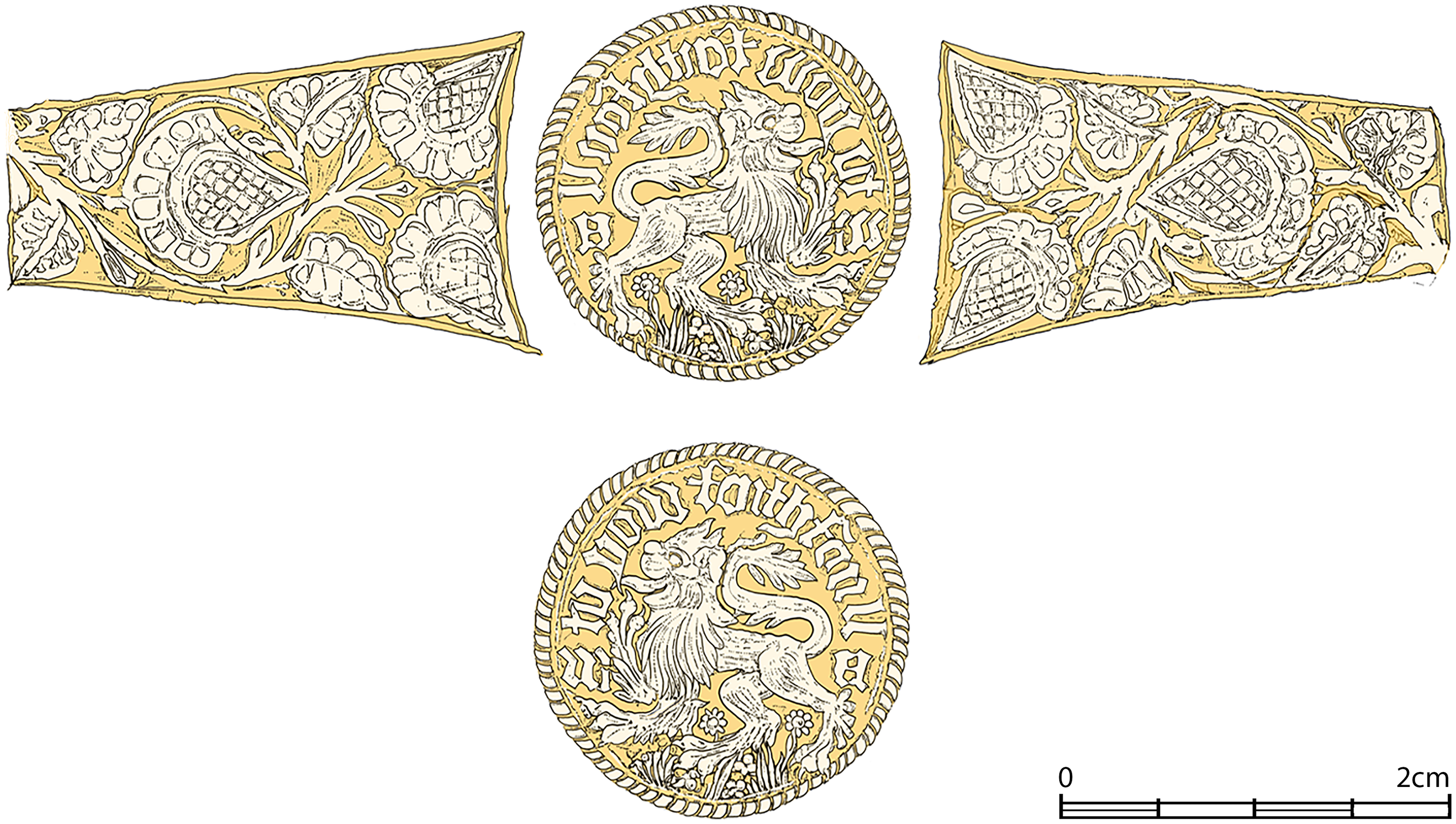

The ring is very large, the hoop having an internal diameter of 22mm and weight of 47.97g. It has a circular matrix (diameter 17mm) bearing the design of a lion passant on a bed of flowers, within single cable border, and the legend (read left to right) to yow feythfoull in Black Letter minuscule (or feythfoull to yow if read from the top; figs 3, 5, 11). The engraving of the lion is finely executed, with not only a full mane, but also fur finely engraved along the torso and hind leg. The individual letters w and a in Black Letter minuscule flank the lion. Each shoulder of the ring is decorated with an engraved panel, filled with three pointed flowers (‘flowers in bud’) on stems, with leaves; there are small bevels to the lower edges of the bezel.

Fig 3. The Raglan ring. Image: reproduced with permission © NMW.

Fig 4. The form of the Raglan ring. Drawing: Tony Daly, reproduced with permission © NMW.

Fig 5. The motifs and legend on the Raglan ring. Drawing: Tony Daly, reproduced with permission © NMW.

Metallurgical analysis

Elemental analysis of the Raglan ring was undertaken by Mary Davis using a Bruker TRACER III-V Light Element Analyzer hand-held XRF, with a rhodium target, a voltage of 40kV and a beam current of 9.6μA. The readings were taken from three different areas of the ring for one hundred live seconds.Footnote 6 This established that the composition of the Raglan ring is approximately 82–4 per cent gold, 10–12 per cent copper and 5–6 per cent silver. This has previously been indicated by the specific gravity of 14.28±0.01, which suggested that the alloy had a silver component with copper impurities (pure gold has a specific gravity of 19.3).Footnote 7

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

It can be difficult to identify with any certainty the devices on fifteenth-century rings, and the original owner of the seal created by this matrix has yet to be proven. The issue of original ownership and wider significance is currently reliant on an assessment of factors such as: form, motifs and date; legend and initials; and findspot.

Form

The form of the Raglan ring with hoop of thickened D cross-section is not in itself unusual, and similar to that of other late medieval signet rings (fig 4). These include the gold signet ring of John Devereux (V&A acc. no. M.215-1975; fig 7, right) and the so-called ‘Percy’ signet ring (with slightly fluted hoop), found on the site of the Battle of Towton, North Yorkshire (1461) and attributed to Henry Percy, third earl of Northumberland (1421–61) (fig 8 no. 2).Footnote 8 The Raglan ring is, however, distinguished by its large size and weight, and by the quality of the engraving.

Fig 6. Other rings with floral decoration: 1) the gold episcopal ring of John Stanbury, Bishop of Hereford (1452–74); 2) the Godstow ring (BM AF.1075). Drawings: reproduced from Merewether Reference Merewether1844; Dalton Reference Dalton1912, no. 962.

Fig 7. Left: gold signet ring bearing the Black Letter inscription my wille were and bezel engraved with a cradle (V&A acc. no. 903-1871, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121103/signet-ring-unknown/). Right: gold signet ring of John Devereux (V&A acc. no. M.215-1975, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O121102/signet-ring-unknown/). Images: reproduced with permission © V&A.

Fig 8. Other jewellery with floral decoration: 1) Episcopal ring of William Wytlesey, Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 1374); V&A M.191-1975. Photograph: reproduced with permission © V&A. 2) The ‘Percy’ ring with its inscription now:is•thus. Photograph: reproduced with permission © The Trustees of the BM, all rights reserved. 3) The Winteringham cross pendant. Photograph: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/469929.

Motifs

The principal motif of the lion passant is walking forward (jaws open, tongue protruding), neither checking the viewer (gardant) nor keeping an eye out for who might be creeping up behind (regardant), nor bellicose (rampant) (figs 5, 11). Several notable Welsh names are recorded with a lion passant. These include Rhys ap Tewdwr (c 1040–93) (later associated with a lion rampant), Cydifor Fawr of Dyfed (d. 1089) and Jenkin Llwyd of Pwll Dyfach (high Sheriff of Carmarthenshire, 1539), and various north Walian families.Footnote 9 A lion sejant gardant was used on William Herbert’s official seal of 1449/50,Footnote 10 and two as supporters by his son,Footnote 11 and there were three lions rampant in the Herbert arms. While one might expect the principal device on a prestigious ring like this to be heraldic, it probably marks an important romantic alliance, the lion on the move to be interpreted as a great man at ease, confident in strength and security. Arguably, the lion references the heraldry and status of a family represented, and at the same time symbolises the ideals of boldness/steadfastness and loyalty.

Pointed flowers appear on early Limoges work, such as a casket with troubadours and imagery drawn from love poetry from the court of Aquitaine, c 1180, in the collections of the British Museum;Footnote 12 often described as ‘flowers in bud’ that are ‘turgid with expectancy’, they form an important element of the poetry of the casket’s theme.Footnote 13 Flowerwork engraved on the shoulders of signet rings is characteristic of some English rings of late medieval date.Footnote 14 As well as an expression of natural beauty, fragrant flowers and odours were generally accepted as a sign of virtue and grace.Footnote 15 The flowers and foliage on rings fall into distinctive types, such as flowers in bud, quatre-, penta- and hexafoils, rose and lily, with a variety of leaf forms (fig 6). They can appear in combination, such as the pair of pointed ‘flowers’/‘flowers in bud’ flanking one that has burst into bloom (a pentafoil), within decorative panels on the shoulders of a fifteenth-century gold signet ring bearing the Black Letter inscription my wille were and with a bezel engraved with a cradle (fig 7, left).Footnote 16 Filling the corners of the shoulder panels, the form of the flowers in bud is in part dictated by the intention to fill the panel, while the ensemble references Spring and an advanced state of love. Similar flowers in bud also occur on the shoulders of a late fifteenth-century gold signet ring with a circular bezel engraved with a hand holding five flowers in bloom and the Black Letter inscription iohn: devereux (fig 7, right).Footnote 17 Flowers in bud also occur on other objects, such as the tau-shaped cross pendant capsule from Winteringham, South Humberside, North Lincolnshire (dated c 1485), where they have been engraved in the corners of panels on both obverse and reverse faces (showing the Virgin with Christ Child, and the Trinity; fig 8 no. 3).Footnote 18

Sometimes leaves, rather than flowers, occupy the acute angled corners of decorative shoulder panels, a fashion from the mid-fourteenth century. This is the case with the floral spray decorating each shoulder of a decorative ring set with a sapphire said to come from the grave of William Wytlesey, Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 1374) (fig 8 no. 1).Footnote 19 Here, leaves occupy the corners, and quatrefoils occur lower down the stem. Other signets with pointed flowers on the shoulder include two in the British Museum collections,Footnote 20 and the so-called ‘Duchess of Lancaster’ late fourteenth-/fifteenth-century posy ring with cusped bezel set with cabochon sapphire (similar to William Wytlesey’s) and Black Letter inscription alas for faute, whose shoulders are engraved with hexafoils with pointed foliage filling the top panel corners.Footnote 21 The decision to fill decorative background panel corners with foliage and forget-me-not flowers can also be seen on the mid-fifteenth-century gold ring found at Godstow Nunnery, Oxfordshire (which originally had an enamelled background; see fig 6 no. 2).Footnote 22 They occur on the shoulder panels filled with black enamel of an unprovenanced late fifteenth-/early sixteenth-century gilt brass signet ring with oval bezel engraved with a merchant’s mark, and inside the hoop the legend I leve yn hope.Footnote 23

Recently found examples of finger rings with flowerwork include a gilt copper-alloy signet ring found in March 2017 at Michaelston-y-Fedw, Newport (fig 9).Footnote 24 This has an oval bezel with a single cable border, and around a central device is a four-stringed harp above floral sprigs, with a pentafoil on leafed stem above the harp. Its shoulders are decorated with a central pentafoil flower flanked by quatrefoil flowers, all on stems with leaves, in a vase. The fields above the flower heads are cross-hatched, possibly for enamel or niello. There are letters p and ur flanking the harp in Black Letter, suggesting the word pur (borrowed from Old French into both Middle English and Middle Welsh: ‘pure’, ‘true’, ‘genuine’, ‘clear’ or (Welsh) ‘faithful’), the letter forms being recorded on seals used c 1444–78.Footnote 25 Consequently these letters do not represent the initials of the owner or Christian names, as proposed for the Raglan ring, but purity represented by the flowers and harp, perhaps a love token as in ‘if music be the food of love’. One can also suggest that the harp could associate the ring with the bardic profession, as by the fifteenth century many will have been gentry to some degree.Footnote 26 Stylised flowers in bud above cinquefoils also decorate the shoulder panels of a large silver signet whose bezel is engraved with cock and hen (an allusion to a loving relationship) found at Holt near Wrexham in about 1994 (fig 10).Footnote 27

Fig 9. Gilt bronze signet ring from Michaelston-y-Fedw, Newport. Photograph: reproduced with permission © PAS Cymru.

Fig 10. Silver signet ring from Holt, near Wrexham (NMW acc. no. 94.23H). Drawing: Jackie Chadwick, reproduced with permission © NMW.

Fig 11. Impression (left) from the matrix on the Raglan ring. Photograph: reproduced with permission © NMW.

Unlike the gold episcopal ring of John Stanbury, Bishop of Hereford (1452–74; see fig 6 no. 1) and perhaps the Michaelston-y-Fedw signet, there is no evidence on the Raglan ring for an enamelled background to the shoulder decoration. However, coloured enamel has survived on a number of recent fifteenth-century rings (eg one found in 2002 at Orton, Cumbria, with green in the leaves and stem of the flowers on the shoulders).Footnote 28 If coloured enamel (green, white, red, blue) or black niello had once been pressed into place without keying, no trace of this survives. Pointed flowers/flowers in bud also appear on objects such as knife handles – such as the hilt of the late fourteenth-/early fifteenth-century French set of knives decorated with the arms of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy (1371–1419)Footnote 29 – and feature in the developed illuminated borders to fifteenth-century Books of Hours, which evoke a variety of flowers such as violets, irises, thistles, columbines, daisies and so.Footnote 30 However, close manuscript parallels to motifs engraved on the Raglan ring as pointed flowers (rather than flowers in bud) are hard to find. Early herbals describe Fritillarea meleagris (fritillary), named after the dice-box chequerboard patterning on the flowers,Footnote 31 but the pattern on engraved pointed flowers is more likely to be stylistic rendering rather than a realistic portrayal of actual features on petals. A special feature of the Grande Heures of Anne of Brittany (c 1500–08)Footnote 32 is the botanical accuracy with which flowers are depicted. The form of pointed flower with lower leaves on folio 69, identified as solanum dulcamara L. (sometimes known in French as morelle douce-amère, or in English bittersweet or woody nightshade),Footnote 33 is reminiscent of, but not sufficiently close to, the form of pointed flower on rings. There is also some resemblance to the strawberries in the margin of the copy of Jean Froissart’s Chroniques (book 3) by the Master of the Getty Froissart (c 1480–3),Footnote 34 and those on Paris of about 1470.Footnote 35 It has been suggested that the ‘flowers’ could represent fruit such as red raspberries, Rubus idaeus (associated with kindness), or blackberries, the fruit still on the bush.Footnote 36 Allegorical and symbolic meanings could vary – strawberries (Fragaria vesca) ‘could just as well suggest sensual delights as the sweetness of Christian purity, or drops of Christ’s redeeming blood’.Footnote 37

Pointed flower motifs rising from collars of downward-pointing sepals also occur in other media, such as a fifteenth-century stove tile from Strömgatan, Bondeska palatset, Stockholm,Footnote 38 and carrot-shaped flowers painted on the walls and ceiling of Christian i’s chapel in Roskilde Cathedral, built in 1460. These are sometimes described as idealised acanthus flowers (Acanthus mollis) and occur on other objects such as tin-glazed earthenware tiles from Middelburg in The Netherlands (dated c 1565).Footnote 39 The leaves on the Raglan ring recall similar fleshy fronds of acanthus, whose swirling tendency is reflected in the stem pattern. Acanthus replaced vines as the dominant leaf in manuscript borders during the fifteenth century. However, the pointed form of the bud is a useful stylistic device to occupy corners, pointing to the stylistic horror vacui of the goldsmith involved.

The chequerboard patterned circular fruit associated with foliage also occur on floor tiles dated 1450–80 from Raglan Castle Chapel and Monmouth Priory,Footnote 40 but this appears to be a standard grape vine motif.

Date

On the basis of the ring form, letter forms, signet device and lettering, and above parallels, the Raglan ring is likely to date to the mid- or third quarter of the fifteenth century (about 1440–75). The distinctive form of the Black Letter w resembles those on seals dated 1461/1462,Footnote 41 and the h in ‘feythfoull’ has the distinctive right descender found of seals used about 1452 (fig 11).Footnote 42 As referenced above, pointed flowers appear on a range of rings and pendants attributed to the second half of the fifteenth century, some closely dated, some less so. A closely dated parallel to the Raglan flowerwork occurs on the shoulders of the ring found on the body of Bishop John Stanbury (see fig 6 no. 1).Footnote 43 Its shoulders are divided into two decorative panels, each having two ‘pointed flower heads’ on stems, one above the other, reserved against a blue enamel background.

Legend and initials

As a signet ring, the legend could have been read from the top, changing the word order to feythfoull to yow, but the word order mirrors the sentiment of the Norman-French personal motto to you loyaul. Both express the wearer’s fidelity as well as love and the strength on bonds (reflecting familial and political ties). This being the case, the initials w and a may be initials for two forenames, rather than forename/surname. For example, ‘W’ might stand for William or Walter and ‘A’ for Agnes, Alice or Anne. The appearance of initials flanking a motif are paralleled by a fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century copper-alloy signet ring from York engraved with a cock, between the letters A and I, possibly the badge of the Ingram family.Footnote 44 The distinctive form of the Black Letter w is closest to that used in 1461 published by Kingsford, and unlike sixteenth-century examples.Footnote 45

The size of the ring suggests that it was worn by a man. The initials, which are clearly part of the original design, are unlikely to be those of Sir William Allington (d. 1479), the loyal supporter of Edward iv appointed to enquire into waste and disturbance in the lordships of Kidwelly and Ogmore, and nominated justice to hold sessions in the lordships of Monmouth, Kidwelly and Ogmore.Footnote 46 The Allington arms are a bend or a lion rampant, and the crest a talbot or a buck’s head (depending on the branch of the family). Nor are they likely to be those of William Ayscough, Bishop of Salisbury (murdered 1451), who married Henry vi to Margaret of Anjou.

The mid-fifteenth-century ring with a bezel engraved with the Black Letter inscription soulement une (‘only one’) above a bear and ragged staff (the badge of the Earls of Warwick) and on the hoop the oath by a part of the deity, be goddis faire foote, shares the strong visual impact of the Raglan ring.Footnote 47 It is said to have been discovered on the body of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (1428–71) on the battlefield at Barnet, though no written record for this provenance exists before the eighteenth century.Footnote 48 Just as the Raglan ring motto lacks any known association with the Herberts, the motto and oath of the ‘Neville’ ring are not otherwise associated with the earls of Warwick. If not actually worn by Herbert’s nemesis, it may have been worn by a supporter, and the same argument might apply to the Raglan ring. A similar legend – loylement une – also occurs on a silver gilt signet ring again engraved with bear and ragged staff (for earl of Warwick) with hoop engraved be goddis f(air)e foot (dated to the early sixteenth century).Footnote 49

FINDSPOT

In attempting to identify the most likely original owner of the ring, the findspot may be significant, as in the case of the Middleham jewel.Footnote 50 It is likely that Sir William ap Thomas (d. 1445) began the construction of the castle at Raglan following his purchase of the manor of Raglan from the Berkeleys in 1432. The building programme was continued by his wealthier son, William Herbert, first Earl of Pembroke (c 1423–69), and the castle was remodelled on a grand scale to reinforce and project his position as the most important Welshman in south Wales and premier supporter of the House of York. Much of the present castle’s appearance, with two courts, hall and chapel, is the result of his planning and financing, and this construction programme continued right up to his death in 1469.

William Herbert inherited a maintained landscape and a great park around the castle,Footnote 51 where he could offer hospitality equal in magnificence to that of any other magnate in the land. Raglan was a ‘palace-castle’ praised in a cywydd (praise poem) by Dafydd Llwyd of Mathafarn, with its ‘hundred rooms filled with festive fare, its hundred chimneys for men of high degree’. Guto’r Glyn called it the ‘air rock-built court of Raglan’ and appears to describe its Great Tower that ‘stands above all other buildings’. Poets Hywel Dafi, Lewys Glyn Cothi and Hywel Swrdwal also sang before him, while Huw Cae Llwyd, Guto’r Glyn and Hywel Swrdwal composed elegies for him after his death.Footnote 52

Remodelled by the later Herberts, Raglan Castle continued to serve as a hugely influential cultural centre through to the Civil War, and Herbert’s influence through his patronage of poets may, as Dylan Foster Evans has pointed out, reflect his mastery of public discourse.Footnote 53 Its many visitors will have entered via the gate-passage on the south side of the castle, having passed through the precursor of two of the three parks of the later owners, the Somerset’s (earls of Worcester), recorded on Laurence Smythe’s 1652 map as part of the estate: Home Park (or Upper Park) and Lower Park (there was also a deer park set up by 1454 about five miles north-west of Raglan Castle at Llantilio Crossenny).Footnote 54 The fishponds are first recorded in 1465, in an inquest following the drowning of a child ‘in the waster called “la fyscche Pole”’.Footnote 55 Following William Herbert’s death, Raglan remained in the hands of his widow Anne Devereux (d. c 1486), but there appears to have been a hiatus in major building work, apart from repairs and minor works, until the upgrading work of William Somerset, third earl of Worcester, who inherited the castle in 1549. The findspot lies just outside the boundaries of Upper and Lower Park as defined in the seventeenth-century Smythe map, on land labelled ‘Powells Land’, and presumably close to the late medieval park boundary.

OWNERSHIP

The ring is the finest known example of mid-fifteenth-century gold jewellery found in Wales, made at a time when it was the custom for ‘courtly’ rings to be presented to the sovereign, princes, great officers of state and ecclesiastics, nobles, legal and other dignitaries and personal friends. Weight and value of such rings would diminish with the rank and importance of the recipient. As a personal signet ring and masculine accessory for rapidly sealing closed correspondence, its large size (over 47g) suggests that the owner was of high rank.

In view of the quality, prestige and date of the ring, its place close to Raglan Castle and the occurrence of the initials w a, it is by no means absurd to consider the possibility that William Herbert, first Earl of Pembroke may himself have been its owner. Son of Sir William ap Thomas and Gwladus (d. 1454), he was brought up at Raglan during Richard, Duke of York’s lordship of Usk. A soldier and administrator, William married Anne Devereux at Hereford in 1449. She was daughter of Walter Devereux of Weobley and Bodenham in Herefordshire (d. 1459), and sister of Sir Walter Devereux (1411–59), later first Baron Ferrers of Chartley. If the initials stand for the first names of husband and wife, the motto could be regarded as an amatory expression of William’s feeling toward his wife, making the motto a private one, while at the same time echoing fidelity to the Crown and reflecting loyalty in royal office (a useful affirmation as signets were used as counter-seals).

Initials occur on fifteenth-century signets, often flanking personal marks, such as on a fifteenth-century gold episcopal signet ring bearing the legend Joye sans fyn from the United Kingdom, now in the Griffin Collection, Metropolitan Museum, New York,Footnote 56 and a mid- to late fifteenth-century gold signet ring engraved with a standing heraldic dragon passant sinister with wings addorsed and mouth open, palm branches above and behind, which has a letter ‘S’ before it, within the Latin retrograde Black Letter inscription + Crede.et.vi[n]c[e] (‘Believe and Conquer’), and it has been suggested that the letter ‘S’ may refer to the name of the original owner.Footnote 57 The mid-fifteenth-century date of the inscription on the Raglan ring indicates that it was possibly created at about the time of William and Anne’s marriage, during the first reign of Henry vi (1422–61). William was knighted by Henry vi in 1452, and by 1453 was the sheriff of Glamorgan. While his activities in the mid-1450s appear to have been in support of the House of York, William did not support the Yorkist cause at the battles of Blore Heath (23 September 1459) or Ludford Bridge near Ludlow, Shropshire (12 October 1459), instead adopting a neutral stance. Receiving rewards from the House of Lancaster for non-participation, he was a reputed Lancastrian until as late as June 1460.Footnote 58 His elusive allegiance changed in 1461 when he decided to support Edward, fourth duke of York, and played a leading role in the defeat of the Lancastrians at the battle of Mortimer’s Cross near Wigmore, Herefordshire, on 2 February of that year. He became the most prominent Yorkist supporter in Wales, and was made Life Chamberlain of South Wales and steward of Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire, and chief justice and chamberlain on Edward’s coronation in 1461 (later in July in the same year being made Baron Herbert of Raglan). In March 1462 he was made knight of the Garter, and in 1466 his son was married to the queen’s sister, Mary Wydeville (Woodville).Footnote 59 He was present at the formal installation of George Neville as chancellor on 10 March 1461 and is one of two men referred to as the ‘chosen and faithful’ of the new king.Footnote 60

The first ennobled Welshman, a privilege granted by Edward in gratitude for the recapture of Harlech Castle in 1468, William lavished his great wealth on continuing his father’s building programme on his ‘veritable palace’ of Raglan Castle until his execution after the battle of Edgcote near Banbury in 1469.Footnote 61 He was certainly wealthier and more politically powerful than his father during his short life, even being viewed by poets as a leading candidate in the role of ‘national deliverer’. Accounts for Raglan Castle attest his presence at Raglan in the 1450s and 1460s (spending little time in London).Footnote 62

Flowers in bud or about to flower may have had a particular significance for William and Anne. This may be indicated by the lavishly illustrated manuscript copy of John Lydgate’s Troy Book and Siege of Thebes (British Library Royal 18.D.ii), written for William Herbert and Anne Devereux as a gift to the king, copied between 1457 and 1460.Footnote 63 It is now thought probable that William and Anne designed the book as their presentation gift to Henry vi (b. 1421, d. 1471), after the king pardoned Herbert for his assistance to the Yorkists, and before Herbert received the Garter from Edward iv in 1462. Folio 6r is headed by the famous scene of the king enthroned surrounded by courtiers with William Herbert and Anne Devereux kneeling before him (book 1; fig 12); their portraits, and arms with mottoes e las sy longeme[n]t and De toute (perhaps a truncated form of De Tout mon Coeur, ‘with all my heart’) appear on the same folio, in scrolls across the top of the page. Other husband and wife mottoes (expressions of loyalty and affection) are known, such as John, Duke of Bedford’s A vous entier and his wife’s J’en suis contente.Footnote 64

Fig 12. The king (probably Henry vi) enthroned, surrounded by courtiers, with William Herbert and his wife Anne Devereux kneeling before him (British Library Royal 18.D.ii, fol 6r). Photograph: reproduced with permission © British Library Board 12/10/2020.

The illuminated letter O of the incipit – O mighty Mars, that with thy sterne lyght In armes hast the powere and the myght – has a strawberry/raspberry-like fruiting flower inhabiting the letter, positioned immediately below the figure of William. A similar selection of motifs appears on the shoulders of the signet engraved John Devereux (see above), though it is unclear who its inscription refers to. One of Anne Devereux’s brothers was a John (b. c 1438), and Sir William’s supporters included his father-in-law, Sir Richard Devereux.Footnote 65 The flowers on the shoulders of the Raglan ring probably conveyed multiple meanings, one of love, another of a wife’s support for her husband (perhaps the mighty lion of Herbert, which also walks on a bed of flowers).

The suggestion, therefore, that the Raglan ring may have been that of William Herbert remains, on the available evidence, circumstantial but attractive. The names William, Walter and Anne were common at this time, and the motto is unlisted. No impressions of this matrix have yet been identified. As stated above, William Herbert did not use a lion as his badge,Footnote 66 though his seal as William Herbert, knight, senseschal of Usk and Caerleon, of 16 January 1449/50 bears a lion sejant gardant.Footnote 67 To complicate matters, his second son Walter’s supporters were two lions,Footnote 68 his wife was also called Anne (Stafford) and he also lived at Raglan. However, identification of the initial with this Walter, who was born about 1452, would imply a later date for the ring (1470s?), which is not supported by the stylistic and palaeographic evidence.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The power of historical figures to grip the imagination has encouraged the identification of links – some proven, some aspirational – between jewellery and individuals. Certainly, cost limited ownership to the wealthy elite. Rings with clear associations include bishop’s rings (eg that of Bishop John Stanbury) and signets with identifiable owners. Rings with less secure associations include the gold signet bearing a lion statant regardant and the Black Letter inscription now:is•thus associated with Henry Percy, third earl of Northumberland, who was mortally wounded on the battlefield at Towton (fig 8 no. 2).Footnote 69 However, neither the lion statant nor the motto are known to have been used by his family.

At present, all that can be safely inferred is that the Raglan ring, the largest and most ornate late medieval gold signet yet found in Wales, was a mark of high status and aristocratic rank, made to order from a goldsmith in England (perhaps in Hereford or London).Footnote 70 It belonged to an individual of high position (politically and economically) present at Raglan during the second half of the fifteenth century – a notable example being the young Henry Tudor, who was in ‘safe-keeping’ in the castle from 1462 to 1469 (aged 5 to 12). Polydore Vergil recorded that Henry considered himself ‘kept as a prisoner, but honourably brought up’, while Bernard André recorded in his Life of Henry VII (written 1500–2) that ‘after he reached the age of understanding, he was handed over to the best and most upright instructors to be taught the first principles of literature’ and also received military training, as befitting his status as a noble youth.Footnote 71 Herbert also appears to have intended to integrate Henry into his family by marrying the boy to his daughter, Maud.

Edward iv’s reliance on William Herbert gave him considerable wealth, a mark of the king’s personal favour being celebrated by Lewys Glyn Cothi, who described him as Edward’s ‘master-lock’ in Wales (‘unclo’r Cing Edwart yw’r Herbart hwn’).Footnote 72 The ring’s large size suggests that it may have been worn over a thumb, large finger or fine glove. When was it lost? It was not cancelled. Signets were useful for sealing private correspondence and in rapid transactions when on military campaign (fig 13). If the hypothetical Herbert association remains credible, circumstances might include loss during duties around ‘Ragland’, during riding or falconry, or during muster, such as the gathering of a force in 1469 to join Edward iv at Nottingham to counter the rebellion in the North led by Robin of Redesdale. Travelling via Monmouth and Gloucester, the force joined up with the Earl of Devon, but before they could meet up with Edward’s army they encountered Redesdale’s force (which had marched south intending to join the Earl of Warwick’s army) at Edgcote near Banbury on the eve of St James’s day (‘noswyl Iago’, ie on 24 July). The supporters of Edward iv were defeated, William Herbert and his brother were captured, and both were executed at Northampton a few days later day. His will, dated 16 July 1469 and made in the Trinity Church of Llantilio, states ‘I will if my wife will take the mantle and the ring and live as a widow, I will that shee shall have all the lordship of Chepstowe and leave Ragland unto my son, Dunster …’.Footnote 73

Fig 13. The Raglan ring: an imagined history? Photograph: reproduced with permission © NMW.

The Raglan ring provides a tangible manifestation of how jewellery conveyed different messages to different people: for the wearer, the detail conveyed a personal bond and faithfulness; to the onlooker it proclaimed rank and wealth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank David Williams, Tom Lloyd and Michael Siddons for comments on the seal; John Kenyon for comments on Raglan and for reading the manuscript; George Hutchinson, former Head of Botany, AC-NMW, and Sally Whyman (Department of Natural Sciences, AC-NMW) for comments on the flowers; Tony Daly and Jackie Chadwick for the line drawings and figure preparation; Jim Wild, Robin Maggs (AC-NMW) and Mark Lodwick (PAS Cymru) for photography; Mary Davis and Mike Lambert (formerly of AC-NMW) for analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- BM

-

British Museum, London

- BNF

-

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

- Getty J Paul

-

Getty Museum, Los Angeles

- Met

-

Metropolitan Museum, New York

- NLW

-

National Library of Wales

- NMW

-

National Museum Wales

- PAS

-

Portable Antiquities Scheme

- V&A

-

Victoria and Albert Museum, London