On 4 February 1742 at an ordinary meeting of the Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries at the Mitre Tavern in Fleet Street, London, William Oldys presented for inspection:

an old drawing upon vellum, with a pen, about 5 feet long, and one foot broad, made in honour of John Islip Abbot of Westminster, a man in great Favour with King Hen VII and a great benefactor to the said Abbey. He dyed [sic] Jan 1532 the beginning of K Henry VIII and soon after his death this drawing was made.Footnote 1

The antiquarian William Oldys (1696–1761) was at that time in somewhat straitened circumstances, and was working primarily for a number of booksellers. Only eight months previously, he had been the literary secretary of Edward Harley, the second Earl of Oxford and Mortimer. But on Harley’s death on 16 June 1741, Oldys was forced to take what bibliographical work he could find, and was eventually reduced to such penury that ten years later his debts drove him into the Fleet Prison, from which he was rescued only by the generosity of friends.Footnote 2

The ‘curiosity’ that Oldys presented to the Antiquaries in 1742 was what is now known as the Islip Roll, an exquisite mortuary roll drawn up to mark the death of John Islip, Abbot of Westminster. Islip actually died on Sunday 12 May 1532.Footnote 3 This roll features a wonderfully delicate and accomplished set of drawings, in pen and ink, on high-quality vellum; two of these drawings provide the only reliable pre-Dissolution views of the interior of Westminster Abbey. As such, the drawings are historically significant, as well as being of great artistic importance.Footnote 4

Fig 1 Abbot Islip’s rebus, the Islip Chapel, Westminster Abbey, c 1525. Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

ABBOT JOHN ISLIP

Abbot Islip, the subject of the mortuary roll, was the last major abbot of Westminster. He was born on 10 June 1464 at Islip, in Oxfordshire, a manor that had a long and close association with Westminster Abbey.Footnote 5 Edward the Confessor, who had himself been born at Islip, had granted the manor to the abbey four centuries earlier.Footnote 6 It is possible that the future abbot was in fact the son of, or at least related to, the local miller, Nicholas Barton, and his wife, Isabella.Footnote 7 But his potential must have been spotted at a young age, quite possibly by the then abbot of Westminster, John Estney. Islip was clothed as a Benedictine monk in 1480, adopting the toponym ‘Islip’ in recognition of his origins.Footnote 8 He rose swiftly through the Church hierarchy, becoming chaplain to Abbot Estney in 1487, and gradually took on various administrative roles within Westminster Abbey: cellarer in 1496 and, soon afterwards, receiver, treasurer and monk-bailiff. In 1498, he was involved in the abbey’s claim to be the proper burial place for King Henry vi, a claim that, although legally successful, ended as a practical failure – Henry vi’s body remained at Windsor, in Berkshire.Footnote 9 In the same year, Islip was elected prior, the second highest position within the abbey, and only two years later, at the age of thirty-six, he was chosen to succeed the brief abbacy of George Fascet.

Islip’s rule as abbot was a high point for Westminster Abbey.Footnote 10 He had significant influence at court with both Henry vii and Henry viii, and was close to most of the major figures of the day, many of whom (including the king) came to dine at the abbot’s house.Footnote 11 He was appointed to various royal committees and fulfilled other administrative roles, including an involvement in the divorce proceedings of Henry viii in the 1520s. But his major achievements were architectural: the chantry chapel in the abbey, which bears his name,Footnote 12 rebuilding the church of St Margaret’s next to the abbey and, especially, the construction of the new Lady Chapel, the foundation stone of which was laid on 24 January 1503 and the consecration of which came thirteen years later, the day after the birth of Princess Mary.Footnote 13

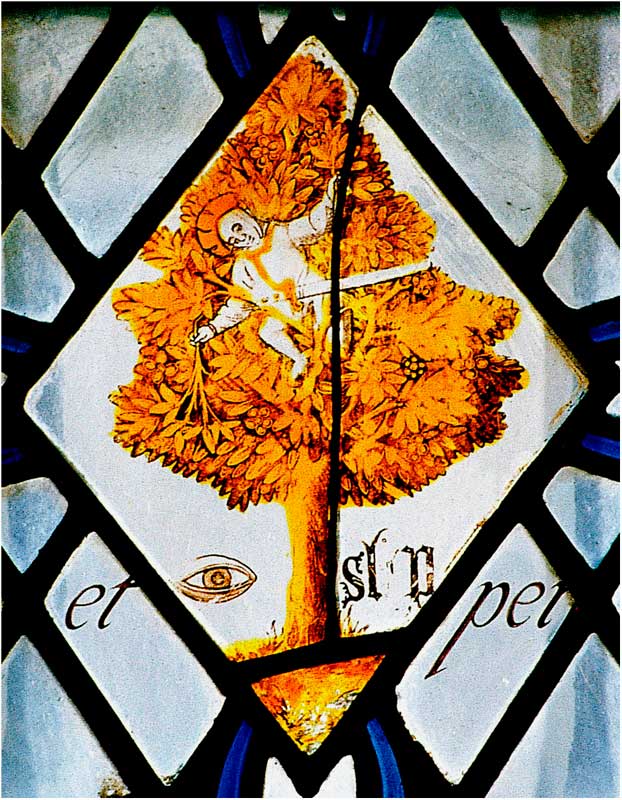

The fabric of the abbey and its precincts was evidently Islip’s chief, although not perhaps his only, artistic interest. A somewhat crude book of devotions of his survives in the John Rylands Library.Footnote 14 In it, alongside the appearance in the borders of a split pomegranate (which might indicate an intriguing relationship with Katherine of Aragon) and the rose, Islip has had introduced his own rebus, of which he was clearly very fond. In this case, it appears as an eye alongside the slip of a plant. In this and other forms, the name Islip can be found repeatedly throughout the abbey. It is, for example, carved onto the outside of his chantry chapel (fig 1). Sometimes he used as a variant an eye and a man slipping from a tree, and this version appears in a glass quarry at the abbey (fig 2). Other similar quarries appear elsewhere, such as in the church of Little Chesterford in Essex (fig 3).Footnote 15

Fig 2 Quarry showing Abbot Islip’s rebus, the Islip Chapel, Westminster Abbey, c 1525. Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Fig 3 Quarry showing Abbot Islip’s rebus, Little Chesterford Church, Essex. Photograph: author

Fig 4 Abbot Islip among the Virtues (WAM, Islip Roll, 1532). Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Abbot Islip’s death on 12 May 1532, and his funeral four days later, were major events. The long procession that accompanied his body included senior ecclesiastical figures, nobles and heralds. A detailed account of the proceedings was drawn up by one of the heralds, presumably by either Christopher Barker, Richmond Herald, or Fulkap Howell, Lancaster Herald, both of whom are listed as being part of the procession.Footnote 16 The requiem mass at Islip’s funeral was conducted by the abbot of Bury St Edmunds and the vicar of Croydon, the notorious Rowland Phillips, preached the sermon. It is not surprising, therefore, that a mortuary roll was also made to mark the occasion.

THE ISLIP ROLL

The roll itself is made up of five scenic panels drawn on three conjoined vellum membranes.Footnote 17 The images the artist (or patron) has chosen to depict were not schematically particularly unusual, but were more numerous and certainly rendered in a more lavish way than any other surviving examples.Footnote 18 These show Abbot Islip standing among the Virtues (fig 4); the abbot on his deathbed at his abbatial residence La Neyte, a short distance from the abbey, in what is now Pimlico (fig 5);Footnote 19 the funeral procession, centred on the magnificent catafalque, reaching the high altar in Westminster Abbey (fig 6); the abbot’s chantry chapel in the abbey, which Abbot Islip himself had had constructed in readiness for his death (fig 7), from which the artist has removed the front wall to enable us to see inside, thus giving us a view of Islip’s own tomb monument (since lost);Footnote 20 and, finally, a decorated initial ‘U’ (fig 8), presumably intended to open the word universis, and thereafter to be followed by the main text of the mortuary roll, which has not, in fact, been written out.Footnote 21 This last drawing contains an image of the abbot assisting at the coronation of Henry viii, the high point of his abbacy, with the exterior of the abbey set over it and (possibly fanciful) building work in progress on the west end as well as our only view of the medieval lantern tower over the crossing.Footnote 22 On either side of the initial are depicted the abbot issuing (or possibly receiving) a document, and a monk passing the document to a messenger. It is possible that this is meant to represent the issuing of the mortuary roll. This last panel, with the absence of text, has led to the understandable suggestion that for some unexplained reason the roll was simply unfinished.

Fig 5 Abbot Islip’s deathbed (WAM, Islip Roll, 1532). Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Fig 6 Abbot Islip’s funeral procession (WAM, Islip Roll, 1532). Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Fig 7 Abbot Islip’s chantry chapel (WAM, Islip Roll, 1532). Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Fig 8 Decorated initial ‘U’ (WAM, Islip Roll, 1532). Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Fig 9 Copy by William Green of the drawing of Abbot Islip among the Virtues, 1728 (Bodl, Gough Maps 226). Photograph: courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

A SECOND MORTUARY ROLL

In 1742, when Oldys displayed it, the roll was actually in the possession of William Green, a sculptor from Wakefield, ‘who’, the Society’s minutes record, ‘is desirous of committing it to the inspection of the Learned and Ingenious Society of Antiquaries for their judgment and advice, through the hands and care of William Oldys, who was desired to accept the Society’s thanks’.Footnote 23 By the following spring, Green was attempting to sell the manuscript, still closely advised, one suspects, by Oldys.Footnote 24 The manuscript had been in William Green’s possession for a number of years, since at least 1728, when it had clearly interested him enough to make a copy of at least one of its panels, that of Islip among the Virtues (fig 9).

Fig 10 Abbot Islip among the Virtues, by George Vertue, c 1743 (Bodl, Gough Maps 226). Photograph: courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

When it was put on display before the Antiquaries in February 1742, the Islip Roll struck a chord with at least one of the Fellows who saw it.Footnote 25 The Society’s official engraver, George Vertue, evidently remembered having seen something similar, and was soon in correspondence on the subject with his friend John Anstis, Garter King of Arms. The letters that passed between them now are among Vertue’s papers.Footnote 26 Two of those that Anstis sent to Vertue from his house in Mortlake were also copied into the Society’s minutes the following May.Footnote 27 The first of these reads:

Sir, I likewise send you the Draughts relating to Abbot Islip’s death and funeral, which probably you might formerly have seen in my Custody, which I brought from Warwickshire long ago. Islip dyed on 12 May 1532, being Sunday. Islip was buried in a chapel of his own building as the Ceremonial expresses.

The first part contains his expiring in a large room (not improbably Jerusalem Chamber \he dyed at the Neyte a house near Millbank/) with the Emblems of the four Evangelists at the corners. The second is his body under the Herse or Chapelle ardent in the Abbey of Westminster with the attendants etc. The third his monument which still remains etc, these two latter shew the Decorations of the figures there in the Abbey.

I have the Heraldic narrative of his funeral from a manuscript of that time.[Footnote 28 ]

I shall send them at any time if the Society have not already seen it. And if thought deserving Engraving, that may be done.

Mortlake

Nov 30 1742

Four months later, on 25 April 1743, Anstis followed this up with another letter, apologising for not yet having sent the ‘draughts’ from Mortlake to Vertue, a misfortune occasioned by the sickness of his waterman, ‘now lately dead’. Anstis explained that he had undertaken a somewhat drastic intervention on the drawings that he acquired:

it was in a long roll miserably ill used before I put it into the frames and got it to be repaired in several places, but I am afraid these amendments decreased the value of it.

What exactly these drawings or ‘draughts’ were that were in Anstis’ possession, and which he had cut up and ‘put into frames’, would not have been terribly clear had George Vertue not taken up the offer of making copies. The drawings that Vertue made are to be found among the Gough papers at the Bodleian Library (figs 10–12).Footnote 29 The ‘draughts’ that Vertue copied were evidently coloured and must, therefore, be an entirely separate set from what now constitutes the Islip Roll (especially as Anstis had cut them into separate panels). These ‘draughts’ were clearly very close to the drawings on the surviving roll, but there are sufficient differences to make it very likely that the items in Anstis’ possession were not simply straight or, indeed, later, fancifully coloured copies. In fact, it seems clear that they must have been portions of another, coloured version of the mortuary roll, for which the surviving Islip Roll represents a highly polished counterpart.

Fig 11 Abbot Islip’s funeral procession by George Vertue, c 1743 (Bodl, Gough Maps 226). Photograph: courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

Fig 12 Abbot Islip’s chantry chapel by George Vertue, c 1743 (Bodl, Gough Maps 226). Photograph: courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

Fig 13 Abbot Islip’s deathbed scene from the Islip Roll, drawing by Samuel Grimm, 1791. Photograph: Society of Antiquaries of London

If that is so, then the Vertue drawings at the Bodleian may represent the only authentic coloured representation of the pre-Dissolution Westminster Abbey in existence and, as such, apparently offer a fascinating new glimpse of how the abbey looked and was furnished in the early sixteenth century. We can assume that Vertue’s drawings afford an accurate representation of Anstis’ original ‘draughts’, at least in the condition that Vertue encountered them (although, it is, of course, possible that the pigments on Anstis’ originals had faded or become corrupted, since they were evidently in poor condition). Vertue was a highly accomplished draughtsman and well able to record items precisely for antiquarian comparison. Indeed, he would have been under specific instructions to do so.Footnote 30 There would have been no reason for him to embellish or invent, and quite strong pressure not to.

HISTORY OF THE COLOURED MANUSCRIPTS

John Anstis stated that he had acquired his drawings in Warwickshire many years before. Although this provides not much more than circumstantial evidence, it is notable that a large proportion of the collection he owned had come from that of the herald Sir Edward Walker, who died in 1677 and had lived the latter part of his life at Clopton in Warwickshire.Footnote 31 It seems quite possible that what was left of the coloured roll – Anstis’ ‘draughts’ – had been in Walker’s possession in the late seventeenth century. Many of Walker’s papers came to him from the Wriothesley family, via Sir William Dethick and Sir William Le Neve. Thomas Wriothesley was Garter King of Arms in 1532 at the death of Abbot Islip, and might well have taken an interest in such a manuscript (although there is no evidence that he was present at the funeral).

What happened to the coloured panels after John Anstis’ death in 1744 is not clear. His papers were kept by his sons until the last of these died in 1768, whereupon they were auctioned off by Samuel Baker and George Leigh in 656 lots.Footnote 32 Unfortunately, there is no specific mention of drawings of Abbot Islip’s funeral among the sale particulars. Lot no. 555 included ‘a portfolio, with some of the prints engraved by the Society of Antiquaries – catafalques of several great men and other prints’, and it is possible that the drawings are covered by this entry. The annotated copy of the sales catalogue in the College of Arms indicates that this lot was purchased by Joseph Edmondson, who was formerly the Queen’s coach-painter and later, after much wrangling with a number of the members of the College of Arms, a herald extraordinary. In 1804, Mark Noble described Edmondson as ‘from humble origin and a mean trade, rose to celebrity. He was apprenticed to a barber, became afterwards a herald painter, and being employed much in emblazoning arms upon carriages, he took a fancy to the science of heraldry’.Footnote 33 In 1767, Garter King of Arms Stephen Martin Leake had been rather blunter in his description, saying that he ‘was a low dirty Mechanick, who by Obsequiousness had insinuated himself into the favour of some of the Nobility’.Footnote 34

Alternatively, it is possible that the coloured ‘draughts’ actually remained in the possession of George Vertue: John Anstis died on 4 March 1744, only a few months after lending them to Vertue, and Vertue may simply never have returned them.Footnote 35 Vertue’s papers are now scattered throughout numerous collections, but many of his drawings were acquired by Horace Walpole, and now form part of the Lewis Walpole Collection in Farmington, Connecticut. As far as can be established, there seems to be no sign of the Islip paintings among them.

The three coloured drawings made by Vertue in 1744, and now at the Bodleian, were purchased in 1772 by Dr Charles Chauncey from the sale of the property of the politician, antiquary and voracious collector of books and manuscripts, James West.Footnote 36 They were probably then bought by Robert Gough in the sale of Charles and Nathaniel Chauncey’s effects in 1790.Footnote 37

Whether the original coloured panels owned by Anstis were acquired by Edmondson, or retained by Vertue, or ended up elsewhere, unfortunately no trace of them has yet been found after the mid-eighteenth century.

LATER HISTORY OF THE ISLIP ROLL

The Islip Roll itself, hawked for sale by William Green in 1743, was eventually bought by Robert Hay Drummond, later to become archbishop of York, but at this point a newly installed prebendary at Westminster. In 1747, with typical generosity, Drummond donated the roll to the Dean and Chapter of Westminster.Footnote 38 His sixth son, George, said of him that,

wherever he lived, hospitality presided; wherever he was present, elegance, festivity and good humour were sure to be found. His very failings were those of a heart warm even to impetuosity.Footnote 39

Forty years later, the then dean of Westminster, John Thomas, once again loaned the ‘curious old drawing upon vellum’ to the Antiquaries to put it before the Fellows, this time in their relatively new rooms in Somerset House.Footnote 40 The dean believed the drawing to be by Holbein, and the minutes give a detailed description of the document taken almost verbatim from the description of it in 1742–3. However, a final flourish was given on the significance of the manuscript:

Abbot Islip laid the first stone of Henry the 7th Chapel in 1502; and dying in 1532 this drawing becomes the more valuable because it not only represents the form of the hearse and the ceremonial and manner of performing the obsequies in that Age; but also shews the structure and appearance of the High Altar in Westminster Abbey before the Reformation; and further shews the original appearance and ornaments of Islip’s chapel and the figure placed under his tomb, which is now destroyed.

Three years later, in 1787, the Society petitioned the dean to allow Samuel Grimm ‘to copy for the use of the Society the Drawing by Hans Holbein of Islip’s funeral in his Lordships possession’.Footnote 41 No response seems to have been forthcoming and so, four years later, in February 1791, it was minuted that:

the Secretary do wait upon the Bishop of Rochester [ie the dean] to obtain permission of his Lordship to have a copy of the drawing of Hans Holbein of Islip’s funeral & to request that the Society may have the use of the drawing for that purpose.Footnote 42

This second petition evidently was successful, for Samuel Grimm was paid 30 guineas by the Society in May 1791 for ‘six drawings taken by him from a roll in the possession of the Dean of Westminster of Islip’s funeral’ (fig 13).Footnote 43 The sixth of the drawings (coloured and labelled ‘VI’ by Grimm) was, in fact, of Islip’s arms, and seems to have been taken from an early sixteenth-century parliament roll of arms.Footnote 44

Fig 14 Engraving of the Islip Roll by James Basire, 1809. Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

The intention had clearly been to make engravings of the individual drawings on the Islip Roll, but for some reason this project took another thirteen years to come to fruition. Why this delay occurred is not entirely clear. James Basire finally produced five engravings from the Grimm drawings of the roll for volume iv of the Society’s Vetusta Monumenta in 1809, for which he was paid the princely sum of 83 guineas (exclusive of copper and writing) (fig 14).Footnote 45

Fig 15 Rubbing of the brass of Abbot John Estney, Westminster Abbey. Photograph: courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Although the roll itself was known to antiquaries, its ownership was now overlooked. The Society became ‘fully under the impression that it was one of their own possessions’.Footnote 46 It was only in 1906 that, by chance, M R James, then provost of King’s College, Cambridge, while working in the Chapter Library,Footnote 47 came across the reference in the Benefactor’s Book to the donation of the roll to the abbey by Reverend Drummond. In May 1906, Dean Armitage Robinson arranged for a letter to be despatched to the Society formally asking for the roll to be returned.Footnote 48 This was finally put into effect at a meeting of the Society, uniquely held at the abbey’s College Hall on 31 January 1907, when, at the end of proceedings, Lord Dillon, the then president of the Society, formally handed back the roll.Footnote 49 In his concluding speech, the dean remarked, ‘and now after a hundred and fifteen years it comes back to us – the Society of Antiquaries having at last finished with it!’ In the course of these arrangements, St John Hope published an investigation of the roll, the only extended study thus far, in the seventh volume of Vetusta Monumenta.Footnote 50

In 1953, the roll was exhibited at the Royal Academy, in an exhibition of Flemish art, at which point a further detailed examination was carried out. It was only then that the attribution to Holbein was dropped, and an alternative authorship of Gerard Horenbout put forward by Otto Pacht.Footnote 51 This attribution was supported by A E Popham, Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, and by Edward Croft Murray, and has not since been significantly challenged.Footnote 52

THE DRAWINGS

In 1906, St John Hope was perplexed by the escutcheons that are to be found on the panel of Islip among the Virtues.Footnote 53 In it, the abbot is shown standing among coils of foliage with scrolls bearing the Christian virtues, managing in the process to incorporate another allusion to his rebus: he holds a slip of this foliage in both hands. But the picture also contains in the frame around the abbot six escutcheons, held by supporting angels. Five of the arms depicted are straightforward, and were straightforwardly explained by St John Hope. Working clockwise from the top left, they are: the arms of St Edward the Confessor, the founder of Westminster Abbey; the arms of St Peter, to whom the church is dedicated; the royal arms; the arms of the abbey; and the personal arms adopted by Abbot Islip himself. These last also appear frequently in his chantry chapel. However, the sixth coat of arms caused St John Hope some trouble. He suggested that they were the arms of the Giles family, but ‘the connexion of this with the abbot has yet to be made out’. He did note that ‘St Giles is one of the prominent figures of saints in the death-bed scene’.

In fact, the arms depicted are those of Islip’s predecessor but one as abbot, John Estney. The arms appeared on his monumental brass, which still sits in the North Ambulatory, outside the chapel of St John the Evangelist immediately to the west of Islip’s own chapel (fig 15). Only indents of the arms now survive. But Henry Keepe, writing in 1683 when the arms were still visible, recorded them ‘on a Fess ingrailed between three Crosses patté, three Martlets’.Footnote 54 In a similar arrangement to the Islip Roll, Estney’s brass also included the arms of St Peter and of the abbey, and at least one other, which Keepe does not identify, but which were probably the Confessor’s arms.

Fig 16 Head of Christ, Torrigiano, c 1515. Photograph: courtesy of the Wallace Collection

John Estney was abbot when Islip first came to the abbey in 1480, and was very much Islip’s patron. Islip seems to have adopted arms modelled on Estney’s, presumably as a sign of debt to his master. But the inclusion of his arms on Abbot Islip’s mortuary roll is noteworthy, and possibly intended to draw attention to the particular role of Estney as Islip’s patron, the person who was abbot when Islip arrived and who was responsible for promoting him through the various offices of the monastery, and to whom he served as personal chaplain.

Further study will be required to unpick all the additional details that the Vertue colour versions of the original Anstis panels reveal about the architectural and decorative interior of Westminster Abbey before the Dissolution. At this point, one or two details may be highlighted, some of which George Vertue himself enumerated in a memorandum, drawn up on the instructions of the Society.Footnote 55

Of the panel showing Islip among the Virtues, George Vertue states that the escutcheons and the inscription (Inquire Pacem et persequere eam):

is wanting entirely in those I have compared with from Mr Anstis; NB it appears by some little remains that such an illuminated partition of this figure of Abbot Islip was joyned to that of Mr Anstis’s, but had been cutt off and is wanting now, but may be happily supplyed by this roll.

That is, Vertue has here filled in the blank. On the third panel, Vertue states that:

every circumstance of the delineation [is] so much alike, that (excepting the coloured blazoning of the coats of arms that adorn the funeral hearse and some inserted mottos) tis all the same.

In fact, it is clear that on this panel there are extra figures introduced on the colour version; that there are only two steps rather than three in front of the high altar; that a great deal more detail is presented as to the polyptych (or painted table above the high altar); that text – a slightly garbled version of the opening words of a refrain from the devotion of the Stations of the Cross, Adoramus Christe et Benedicimus tibi – has been introduced onto the fronting of the altar screen; and that, additionally, we have the colours of many of the features – the covering for the hanging pyx, other cloth hangings, the canopies and testers of the tombs behind the catafalque (bearing in mind, of course, that the colours that Vertue was copying may have degraded).

Likewise, the panel showing Islip’s monument and chantry chapel gives us much more detail in the colour version of the wall paintings around the chapel,Footnote 56 the design of Abbot Islip’s own effigy and of the original colouring on the Head of Christ by Torrigiano, sculpted in about 1520 and now at the Wallace Collection, especially the gilt bronze rays that surrounded the head, most of which are now lost (fig 16). The two that do survive are now covered in black varnish.Footnote 57

Fig 17 Manipulus Florum, manuscript owned by John Fulwell, late 15th century (Peterhouse ms 268). Photograph: courtesy of Cambridge University Library

Vertue’s notes make it clear that when he examined them, there were also coloured versions of the initial letter ‘U’ (which, interestingly, he states did not include the image of the building work over the top) and of the deathbed scene. But if Vertue did produce versions of these, as surely he must have, they do not seem to have survived. The only difference in the two versions of the deathbed scene that Vertue mentions is:

the person that holds the crucifix to the dying abbot has a mitre on, in the roll or first draught, and in the depicted illumination it is a man in his black habit that holds it.

So, St Thomas Becket, who features in the Islip Roll ministering to the dying abbot, has been replaced by a regular monk.

THE PRODUCTION OF ABBOT ISLIP’S MORTUARY ROLLS

The most obvious difference between the two sets of images has been introduced into the picture of Islip’s chapel, and it is this difference, as much as any other element, that confirms that Anstis’ panels came from a separate, yet contemporary, coloured and finished roll rather than from some fanciful later re-imagining of the Islip Roll. In Vertue’s colour version of this picture, a scroll has been added to the bottom of the panel. This scroll bears the legend ‘Mercy and Grace’ repeated on either side of an eagle (the symbol of St John), which holds in its mouth another scroll on which is written the single word ‘FFVLWELL’.

At the death of Abbot Islip in 1532, Brother John Fulwell was a very senior figure at Westminster.Footnote 58 He had entered the abbey in 1508, under Islip’s patronage, and, like his master before him, rose through the ranks of monks. By the 1530s, he had become treasurer, cellarer, warden of the manors of Queen Eleanor, of Richard ii and his wife Anne of Bohemia, and of Henry v. In the 1520s, he had been responsible for the payments for the decoration of Abbot Islip’s own chapel, recently constructed,Footnote 59 and he had served as the abbot’s chaplain, in which capacity he was responsible for organising the furnishings of the new Lady Chapel. In 1526, Fulwell paid £11 5s to the sculptor Benedetto de Rovezzano for one-third of the overall price of a new altar.Footnote 60 He even owned manuscripts. Peterhouse ms 268, in Cambridge University Library, is a small copy of Thomas Hibernicus’ Manipulus Florum, which was owned and inscribed by him, not only with his name, but also with the motto that adorns the coloured version of the mortuary roll, ‘Mercy and Grace’ (fig 17).Footnote 61 Fulwell has also written there two plays-on-words on his name, rather reminiscent of Islip’s rebus: plenus fons and valde bene, both of which might be rendered as ‘Full Well’ (fig 18). It is, therefore, not surprising that Fulwell was chosen as one of the two monks commissioned, on behalf of Prior Thomas Jay, formally to notify Henry viii of the death of the abbot.Footnote 62 It also seems inconceivable that a later copyist, producing a ‘modern’ version based on the Islip Roll, would introduce Fulwell’s name and motto onto a new roll; they would have had no knowledge of his role in the process, and it would have been a notable (and pointless) departure from the original.

Fig 18 Detail of Peterhouse ms 268, showing the play-on-words on Fulwell’s name rather reminiscent of Islip’s rebus. Photograph: courtesy of Cambridge University Library

Mortuary rolls (brevicula), of which relatively few examples survive in England, were usually intended for circulation to heads of other religious houses in order to inform them of the death of a brother abbot, or churchman of similar standing, and invite prayers for his soul.Footnote 63 This is the role particularly ascribed to them in the various Benedictine customaries, including that of Westminster Abbey.Footnote 64 They were to be drawn up by the precentor (or his assistant, the succentor), who, at Westminster in 1532, was Dionisius (or Denis) Dallianns, the other monk chosen with Fulwell to inform Henry viii of Islip’s passing.Footnote 65 The artistic lavishness and accompanying cost of the Islip Roll, and the presence of another, high-status, complementary coloured version, with its own explicit connections with Fulwell (who was neither precentor nor almoner, and, therefore, should not technically have overseen the production of the roll), suggest that one of the rolls may have formed part of this grander process of royal notification and may, therefore, represent a formal presentation copy for the king.Footnote 66 This would explain the employment of such a high-quality artist to compose the pen-and-ink version, and quite plausibly the original coloured version as well.Footnote 67 Unfortunately, no evidence survives of the payment for the production of the rolls. Fulwell’s accounts as treasurer do not survive for the relevant year, even if payment for such work had been recorded in them.Footnote 68 On this reading, only one of the rolls may have been intended to fulfil the more traditional function of notifying other religious houses. As indicated, the lack of requisite text or evidence of tituli suggests that the Islip Roll did not circulate in this way, and implies that this roll at least may have been drawn up as a display or presentation copy. Perhaps circulation in some other form, with a strong element of display, was intended for it.Footnote 69 Its fine quality, and its format, argue against it being a form of preparatory drawing. Such drawings would not have needed to be formed into a roll; individual panels would have been far more efficient for this purpose.

GERARD HORENBOUT

Gerard Horenbout (d. 1540/1), a painter from Ghent, worked for many years at the Henrician court.Footnote 70 He was an artist who worked in a wide range of media: portraiture, maps, stained glass, embroidery and, especially, manuscripts. Between 1517 and 1520, before coming to England, he was responsible for sixteen sumptuous additional illuminations in the Sforza Hours, at the commission of Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands.Footnote 71 He was in England by the mid-1520s, and until at least 1531 (and probably significantly later) produced work for Henry viii. The attribution of the Islip Roll to him or his workshop (which probably included his children) remains persuasive. Similarities between the form of the initial ‘U’ in the Islip Roll, and the form of the decorated initial by his son Lucas Horenbout in the 1524 letters patent to Thomas Forster, Comptroller of the King’s Works, are marked.Footnote 72 Each is made up of acanthus leaves, divided by a central collar. Other parallels may exist with the Spinola Hours, including the architectural framing and foliage in the Tree of Jesse illumination (fol 65) and the cut-away view of the tomb underneath the Office of the Dead (fol 185).Footnote 73 This manuscript was largely illuminated by the Master of James iv of Scotland, who has been tentatively identified as Gerard Horenbout.Footnote 74 Unfortunately, the newly discovered George Vertue drawings, being clearly of lesser quality than the Islip Roll, and at a remove from the original, do not throw any additional light on the original artist.

THE AFTERMATH

In the period after Islip’s death, and during the uncertainty surrounding the choice of successor, John Fulwell may have felt himself one of the candidates for the role. In the event, the appointment was long delayed, and the uncertainty increased.Footnote 75 These were difficult times. On 15 March 1532, Archbishop Warham had publicly upbraided the king in parliament. But two months later, the day before Islip’s funeral, he presided over the convocation that surrendered its legislative independence to the Crown. On the same day, Thomas More resigned the chancellorship and withdrew from public politics. At Westminster, John Fulwell recorded in his treasurer’s accounts of allowances for 1531–32 very sizeable payments that year for hospitality afforded to various barons of the Treasury and other royal officials.Footnote 76 Thomas More is noted at the end of the list; his name has then been crossed out.

Five months after Abbot Islip’s funeral, on 16 October 1532, Fulwell wrote to the ascendant Thomas Cromwell as Master of the King’s Jewells:

Sir, pleaseth it your good mastershipp to understande that all things in the sanctuarye, as well within the monasterie as without, is continued in dewe order accordyng to the advertyssmenet ye gave unto me when I was last with you at London. So that at the tyme of your return home I trust your mastershyppe shall not hear but that we shall deserve the kynges most gracious favour in our suit. And in the meane tyme, my religious father prior, with all the convent, whych lowly doth comende them unto you, besecheyth you of your goodnes to have ther matter in remembrance as ye shall so think convenyent for the furtherance of the same. And ye so doyng, shall bynde them and me assurydly to pray for your prosperous contynewance, as knowethe our saviour Jesus Crist.Footnote 77

Precisely what the purpose of this suit to the king might have been is not specified, but the implication seems to be of a supplication by the monks for a licence to elect a new abbot or, at the very least, for a decision to be taken on ‘ther matter’.Footnote 78 The abbey community was understandably becoming anxious at the prolonged vacancy.Footnote 79 Fulwell’s role in drawing up Abbot Islip’s mortuary rolls (if one was indeed intended for the king), in formally notifying the king of the abbot’s death, and in acting as an apparent link with Cromwell, may have suggested him as a strong candidate for the post. Several apparently extraneous elements that Fulwell had introduced onto the roll, including his name and probable motto,Footnote 80 the associations formed by the juxtaposition of Islip’s arms, as Estney’s former chaplain, with Estney’s own, paralleling Fulwell’s own position as Islip’s chaplain, may perhaps have been intended to ensure that Fulwell was in mind as the decision was taken.Footnote 81

Whatever the hopes of Fulwell and the rest of the community, they were to be denied. On 10 April 1533, William Boston, then abbot of Burton-on-Trent and a friend of Cranmer, was elected to the abbacy.Footnote 82 He was the first outsider from the monastery to be given the position since 1214, over 300 years before. One month later, on the anniversary of Abbot Islip’s death, Boston took the oath to observe the duties of Henry vii’s foundation.Footnote 83 Within a brief period, he had begun to make generous gifts from the abbey to his patron Cromwell; property was mortgaged off or exchanged with Crown lands to the abbey’s great disadvantage, wide-ranging financial changes were introduced (some of which were, it must be admitted, entirely rational) and there followed a ‘studied run-down of the Abbey’s discipline and economy’, until its inevitable surrender on 16 January 1540.Footnote 84 Despite his own protestations, Boston himself was rewarded by being appointed dean of the new cathedral.Footnote 85

Fulwell’s prominence apparently led Cromwell to consider moving him in the reverse direction from William Boston. On 2 July 1533, Cromwell jotted a memorandum noting ‘Item, for the Monk Baylye to be abbot of Byrton’.Footnote 86 Nothing came of this proposal, but Fulwell’s ambitions do not seem to have waivered and on 26 August 1535 the wealthy mercer and future mayor of London, Robert Gresham, sought from Cromwell the favour for John Fulwell to be Prior of Worcester.Footnote 87 Nothing was to come of this either. Fulwell died, still a monk of Westminster, later that year.Footnote 88

Acknowledgements

I am profoundly grateful to Bernard Nurse, who first brought the Vertue drawings at the Bodleian to my attention and discussed their significance with me, and to Dr Lynsey Darby, John Goodall, Dr Charles Knighton, Ann Payne, Dr Tony Trowles and Dr Rowan Watson.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- BHO

-

British History Online

- BL

-

British Library, London

- Bodl

-

Bodleian Library, Oxford

- DCL

-

Durham Cathedral Library

- NAL

-

National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

- SAL

-

Society of Antiquaries of London

- TNA

-

The National Archives, Kew

- WAL

-

Westminster Abbey Library, London

- WAM

-

Westminster Abbey Muniments, London