Horace Walpole’s novel, The Castle of Otranto: a story, published on Christmas Eve 1764, is typically presented as the first ‘Gothic’ novel.Footnote 1 It was not until the second edition of Otranto (1765), however, that the work acquired the subtitle A Gothic Story: only then was it explicitly framed as a piece of ‘Gothic’ fiction. Walpole initially distanced himself from Otranto, instead presenting the narrative as a translation by William Marshal, Gent., from the ‘original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St Nicolas at Otranto’.Footnote 2 The novel’s source, the Preface to the first edition tells us, was a work ‘printed in Naples, in the black letter, in the year 1529’, which was ‘found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England’.Footnote 3 Although apparently of sixteenth-century provenance, the work is dated by Walpole, in the guise of the translator, to the Crusades – to the ‘darkest ages of Christianity; but the language and conduct have nothing that favours of barbarism’.Footnote 4 As if to obscure his authorship even further, Walpole did not have The Castle of Otranto produced at his private printing press at Strawberry Hill, a facility that he had set up in 1757.Footnote 5 It was, instead, published by Thomas Lowndes in London.

Walpole disclosed his deception, however, and acknowledged his authorship of Otranto in the Preface to the second edition published on 11 April 1765:

The favourable manner in which this little piece has been received by the public, calls upon the author to explain the grounds on which he composed it. But before he opens those motives, it is fit that he should ask pardon of his readers for having offered his work to them under the borrowed personage of a translator.Footnote 6

Thereafter the novel has been connected frequently, and understandably, with Walpole’s other notable Gothic ‘output’, his villa, or the ‘little Gothic castle’ of his ancestors, Strawberry Hill, Twickenham (constructed and furnished 1747/8–80).Footnote 7 Indeed, Walpole himself seemed to have prompted this identification when, in the guise of the translator of the first edition of Otranto, he writes that ‘the scene is undoubtedly laid in some real castle’.Footnote 8 Accordingly, like many other visitors to the house after 1765, once Walpole’s authorship of Otranto was disclosed, Frances Burney (1752–1840) found that the villa’s ‘unusually shaped apartments’ offered ‘striking recollections … of his Gothic Story of the Castle of Otranto’.Footnote 9 W S Lewis, the great collector of Walpoliana in Farmington, CT, and executive editor of the extensive forty-eight-volume Yale edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence (1937–83), similarly repeats Walpole’s suggestion that Otranto was based upon a tangible structure:

the castle [of Otranto] itself, however, was Strawberry Hill, as Walpole repeatedly points out. In the first Preface to The Castle of Otranto … he says, ‘The scene is undoubtedly laid in some real castle. The author seems frequently, without design, to describe particular parts. The chamber, says he, on the right hand; the door on the left hand; the distance from the chapel to Conrad’s apartment: these and other passages are strong presumptions that the author had some certain building in his eye’.Footnote 10

Lewis continues by suggesting that it is possible to identify some of the rooms in Otranto as those at Strawberry Hill:

The Gallery at Otranto is the Gallery at Strawberry Hill. The ‘chamber on the right hand’ into which the spectator disappeared at the end of the Gallery and in which he lay down so disconcertingly was the Tribune. This is also the ‘gallery-chamber’ and ‘the great chamber’. Isabella’s chamber, ‘the watchet-coloured chamber’, is the Blue Bedchamber. The Armoury is the same in both castles and so is the ‘principal staircase’.Footnote 11

Sean R Silver also connects the building and novel, but suggests that Otranto reciprocally influenced Walpole’s villa. He writes that ‘Otranto was an experiment in the organisation and display of Gothic artefacts that extends, and in some ways anticipates, ongoing work at Strawberry Hill’.Footnote 12

The materiality and prevailing atmosphere of ‘gloomth’ at Strawberry Hill, together with its ‘active’ architecture that imposes upon visitors a range of transitory and contradictory experiences designed and ‘curated’ by Walpole and the ‘Strawberry Committee’, certainly had a hand in Otranto’s narrative.Footnote 13 The house and novel are, after all, both concerned with the Gothic past. Walpole had been working on Strawberry Hill for sixteen years before Otranto took shape and, given their shared interest in, and references to, medieval architecture and culture, it is perfectly reasonable to see the novel and house as symbiotic, though discrete, manifestations of Walpole’s broad fascination with the Gothic past.Footnote 14 Indeed, their connection is suggested numerous times by Walpole himself. In a letter from 19 June 1774, for instance, he states that ‘I am going to hang them [a pair of shields] by the beautiful armour of Francis I and they will certainly make me dream of another Castle of Otranto’.Footnote 15 Strawberry Hill’s interior, he implies, could spawn another Gothic narrative.

Walpole also anchors Otranto’s genesis firmly at Strawberry Hill in a well-known letter to William Cole (1714–82) from 9 March 1765, in which he recalls the moment in early June 1764 that the novel was born:Footnote 16

I had time to write but a short note with The Castle of Otranto, as your messenger called on me at four o’clock as I was going to dine abroad. Your partiality to me and Strawberry have I hope included you to excuse the wildness of the story. You will even have found some traits to put you in mind of this place … Shall I even confess to you what was the origin of this romance? I waked one morning in the beginning of last June from a dream, of which all I could recover was, that I had thought myself in an ancient castle (a very natural dream for a head filled like mine with Gothic story) and that on the upper-most bannister of a great staircase I saw a gigantic hand in armour.Footnote 17

The staircase mentioned in this letter to Cole is surely that at Strawberry Hill: the Arlington Street townhouse could hardly be considered an ancient castle, nor was its classical style likely to have inspired Otranto by association. It may seem contradictory, however, to see in Strawberry Hill the ‘foundation’ of an ancient Gothic castle given that Walpole’s house was, after all, a modern, suburban villa. Walpole, nevertheless, considered and frequently referred to it in his correspondence as a castle – and an ancient one at that. Writing to George Montagu (c 1713–80) on 11 June 1753, for example, Walpole makes mention of the ‘castle I am building of my ancestors’, its newly built nature notwithstanding.Footnote 18 The house’s historical nature and faux antiquity is developed further in an undated holograph addition to one of Walpole’s personal copies of A Description of the Villa of Mr. Horace Walpole (1774):

The year before the Gallery was built, a Stranger passing asked an old Farmer belonging to Mr Walpole, if Strawberryhill was not an old House! He replied, ‘yes, but my master designs to build one much older next year’.Footnote 19

Thus, although Strawberry Hill was effectively a new and modern structure, it is not unreasonable and unprecedented for Walpole to consider and refer to it as an ancient castle.

In his Description Walpole also emphasises Strawberry Hill’s influence over Otranto’s narrative: ‘at least the prospect would recall the good humour of those who might be disposed to condemn the fantastic fabric, and to think it a very proper habitation of, as it was the scene that inspired, the author of The Castle of Otranto’.Footnote 20 This is what Nick Groom terms the ‘Strawberry factor’ in his Introduction to the most recent edition of The Castle of Otranto (2014).Footnote 21 This ‘Strawberry factor’ was sufficiently powerful for Walpole, on occasion, to refer to Strawberry Hill as ‘Otranto’, of which he was the ‘Master’, while Thomas Chatterton (1752–70), the author of the Rowley poems (1777) whom Walpole later maligned, termed Walpole the ‘Baron of Otranto’.Footnote 22 In addition, a drawing by Lavinia Spencer (née Bingham), Countess Spencer (1762–1831), depicting ‘A young lady reading the Castle of Otranto to her companion; a gracefull and expressive drawing, done for a present to Mr. W.’, was hanging in the villa’s Red Bedchamber by 1784.Footnote 23 Spencer’s drawing not only reinforces the perceived relationship between Strawberry Hill and Otranto in the Georgian period, but also the predominantly female readership of Gothic novels that is equally recorded by James Gillray’s engraving, Tales of Wonder, from 1802.Footnote 24

The link between Strawberry Hill and Otranto, based upon evidence from Walpole and his contemporaries, appears irrefutable. This article does not attempt to challenge the connection and postulated direction(s) of influence between the house and the novel. Instead, it explores a small collection of remarkable and apparently unsolicited watercolours that depict scenes from Otranto. These paintings are mostly by John Carter (1748–1817), the well-known Georgian architectural draughtsman and vocal supporter of medieval architecture.Footnote 25 Paying close attention to these images yields a nuanced reading of the relationship between Walpole, Otranto, medieval architecture and heraldry. Instead of promoting Otranto’s commonly held source as Strawberry Hill, he repeatedly, and occasionally ad nauseam, emphasises Walpole’s role as the novel’s creator: there is no trace of Strawberry Hill – beyond, of course, the broad aesthetic theme. Carter capitalises upon his and Walpole’s congruent interests in the form and visual language of Gothic architecture and heraldry to create bold artworks articulating the associationist powers of the medieval form. Importantly, and until now overlooked, these watercolours also demonstrate an understanding and sympathetic use of the coded language of heraldry, and Carter embraces this visual language to add extra layers of sophisticated meaning to his depictions of Otranto.

Upon publication, Otranto lacked illustrations, and the first engravings were not included until the sixth edition (1791), which was set and printed by Bodoni in Parma.Footnote 26 The six plates included in this edition, after drawings by Anne Millicent Clarke, are not particularly sophisticated and offer only a basic, stage-like, two-dimensional rendering of the scenes’ architectural contexts; instead, it was figures and their clothing and equipage that drew her attention (fig 1). Critical of such illustrations, Walpole wrote to Bertie Greathead (1759–1826) praising four manuscript designs depicting scenes from Otranto by his son, Bertie Greathead Jr (c 1781–1804). In his letter of 22 February 1796, Walpole recounts that:

I have seen many drawings and prints made from my idle – I don’t know what to call it, novel or romance – not one of them approached to any one of your son’s four – a clear proof of which is, that none one of the rest satisfied the author’s ideas – It is as strictly, and upon my honour, true, that your son’s conception of some of the passions has improved them, and added more expression than I myself had formed in my own mind; for example, in the figure of the ghost in the chapel, to whose hollow sockets your son has given an air of reproachful anger, and to the whole turn of his person, dignity.Footnote 27

Fig 1 Theodore & Matilda, from Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto: a Gothic story (1791). Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (pl iii, opp p 142; from LWL, 24 17 791P copy 4)

As Walpole here concedes, illustration had the power to supplement and enrich scenes that had only been loosely sketched out in his literary imagination. In comparison with Clarke’s illustrations, those by Bertie Greathead Jr are complex, and the architectural contexts are convincingly three-dimensional (fig 2).Footnote 28 Significantly, the settings are clearly influenced by eighteenth-century domestic Gothic Revival architecture, though they do not reference specific spaces at Strawberry Hill.Footnote 29 Consequently, Greathead Jr’s drawings are more modest and relatable in comparison with those created by Carter, who produced by far the largest, most important and most ambitious illustrations to The Castle of Otranto.

Fig 2 Bertie Greathead Jr, Frederick and the Spectre, 1796, in Walpole’s copy of The Castle of Otranto: a Gothic story (1791). Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 49 3729)

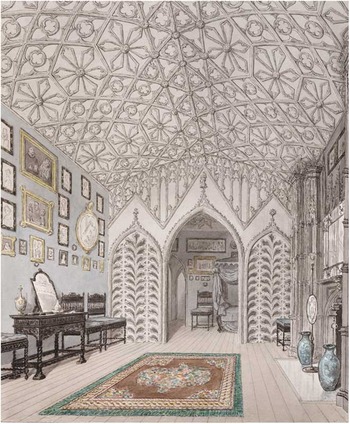

Under Richard Gough (1735–1809), Director of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1771–97), Carter was employed from 1780 to record medieval architecture and its fragments, and he contributed significantly to Gough’s Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain (1786–96), which the Preface to the first volume acknowledges.Footnote 30 Carter had also been introduced to Walpole at this time, and in 1788 he was employed to record Strawberry Hill (fig 3), including its interiors and a number of objects within Walpole’s collection, such as the model of the shrine of St Thomas Becket (fig 4).Footnote 31 Describing his relationship with Walpole in his unpublished Occurrences in the Life, and Memorandums Relating to the Professional Persuits of J C F.A.S. Architect, Carter records that:

Horace Walpole, late Lord Orford, I must likewise number among my Patrons, and as far back as this year made a drawing for him, which occasionally I continued to do until his decease. About the year I was introduced by the late Rd. Bull Esq at Strawberry Hill to make for him a series of views, both external and internal, with … the decorations belonging thereto, with … curiosities, &c. &c. To accelerate this undertaking, Mr. Walpole afforded me every assistance and accommodation. Thus engaged I became acquainted with his right hand man, his chief help in all his purchases of every description, and also familiar intercourse between him and Amateurs of the day.Footnote 32

Fig 3 John Carter, The Holbein Chamber, Strawberry Hill, 1788. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 33 30 copy 11)

Fig 4 John Carter, Model of the Shrine of St Thomas Becket, 1788. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 33 30 copy 11)

In 1790, Carter produced The Entry of Frederick into the Castle of Otranto, a large-scale watercolour (602×503mm) of a scene taken directly out of Walpole’s narrative (fig 5).Footnote 33 There is no evidence to suggest Walpole commissioned it specifically, though it is a natural extension of his commission to delineate Strawberry Hill: the novel was, after all, Walpole’s other significant ‘Gothic monument’. Walpole hung the watercolour in the Little Parlour at Strawberry Hill, and in his personal copy of the Description (1784) bequeathed to him by Walpole, Carter records that he ‘(Was paid for it 20 Guineas.)’.Footnote 34

Fig 5 John Carter, The Entry of Frederick into the Castle of Otranto, 1790. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 790.00.00.138dr+)

This watercolour is unique among the known corpus of Otranto illustrations as no other traced work tackles this part of the novel. Unlike Strawberry Hill’s modest scale and, indeed, that of the real castle of Otranto in Italy – Carter copied a watercolour of the ‘real’ Castle of Otranto in Italy from a drawing made by Mr Reveley (fig 6) – the architectural setting of The Entry of Frederick is vast.Footnote 35 Nine distinct structures ranging in style from Romanesque through to Perpendicular Gothic form three sides of Otranto’s courtyard. These buildings are clearly informed by Walpole and Carter’s shared understanding of, and interest in, the forms and details of medieval architecture. For Carter, this was manifest in the preservation and delineation of buildings and their details, whereas Walpole reproduced medieval architecture and ornament for domestic purposes, including modelling chimney-pieces upon tomb canopies: the gabled-canopy (now removed) over the effigy of John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall, in Westminster Abbey, was the model for the chimney-piece in Strawberry Hill’s library, and the screen of Prince Arthur’s tomb at Worcester Cathedral informed the wallpaper of the staircase and hall.Footnote 36

Fig 6 John Carter, South View of the Castle of Otranto with the Acroccraunian Mountains of Epirus in the Distance. Copied from a Drawing made in March 1785 by M r . Reveley. given to M r . Walpole by Lady Craven, c 1788. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 33 30 copy 11 Folio)

The sophisticated rendition of architecture in The Entry of Frederick clearly resonated with Walpole’s passionate belief that Gothic architecture inspires awe and imagination:

It is difficult for the noblest Grecian temple to convey half so many impressions to the mind, as a cathedral does to the best Gothic taste – a proof of skill in the architects and of address in the priests who erected them. The latter exhausted their knowledge of the passions in composing edifices whose pomp, mechanism, vaults, tombs, painted windows, gloom and perspectives infused such sensations of romantic devotion; and they were happy in finding artists capable of executing such machinery. One must have taste to be sensible of the beauties of Grecian architecture; one only wants passions to feel Gothic.Footnote 37

Indeed, one of the reasons for Walpole’s profound embrace of Gothic architecture and historic relics was their ability to call to mind associations. As I have shown elsewhere, the medieval arts were intimately associated with the idea of chivalry, but the associative principles of Gothic architecture covered other facets of the Middle Ages.Footnote 38 Walpole, in his Books of Materials, writes that:

I believe this approbation [of classical architecture] would in some measure flow from the Impossibility of not connecting with Grecian & Roman Architecture, the ideals of the Greeks & Romans, who invented & inhabited that kind of building. If (which but few have) one has any partiality to old Knights, Crusades, the Wars of York & Lancaster &c the prejudice in favour of Grecian buildings, will be balanced.Footnote 39

The power of association, cultivated in the eighteenth century by Walpole – and, among others, by Joseph Addison (1672–1719) in his Spectator letters (1710–11) – meant that architectural styles were laden with meaning and associated ideas.Footnote 40 Gothic, as Alexander Gerard (1728–95) sternly criticised it in his Essay on Taste (1759), only satisfies those unfortunate enough not to possess ‘enlargement of the mind’: though it offered, for others, a fantastic repertoire of architectural form and ornament quite separate to everyday Georgian life and taste that resonated with ‘old Knights, Crusades, the Wars of York & Lancaster’.Footnote 41 Carter embraces the associative power of Gothic, and The Entry of Frederick is an elaborate response to Walpole’s novel: nowhere in the novel is the castle of Otranto referred to as a Gothic fabric (beyond in the first edition’s Preface where the ‘translator’ dates the narrative to between 1095 and 1243), and it is never presented (explicitly or implicitly) as a vast complex. These features, instead, arise from the novel’s plot, its subtitle (used from the second edition on) and the regard for Britain’s Gothic heritage that Carter and Walpole shared.

Carter’s complex rendering of architecture responds to his occupation as an antiquary and architectural draughtsman. It reproduces, for example, the clutter and omnipresent architectural surroundings of the frontispieces to his Specimens of Ancient Sculpture and Painting (1780–94), the first volume of which was dedicated to Walpole (fig 7): ‘Your kind Encouragement gives wings to my Ambition to continue their Publication, and under your Auspices, I have been able to bring to a Conclusion the first Volume’.Footnote 42 The Entry of Frederick, while a bespoke artwork, is consistent with, and based upon, Carter’s pre-existing canon of faux-historical, associational illustrations that are imaginative, yet shrewdly archaeological and architecturally elaborate. In essence, Carter is using Walpole’s narrative to create more of his extraordinary and highly personal representations of the past: The Entry of Frederick is indebted to Walpole, but what Carter achieves is certainly very different from Walpole’s villa and the objects accreted within it.

Fig 7 John Carter, Specimens of Ancient Sculpture and Painting (1780): frontispiece. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, Folio 46 780C)

Carter’s decision to illustrate Frederick’s entry into Otranto offered him a unique opportunity – one not taken up by other artists – to define and delineate the most complete and complex display of chivalry and pomp in the whole of Walpole’s novel. The themes presented in the illustration – medieval architecture, chivalry, inheritance and usurpation of title and station – are at the heart of Otranto’s plot. Carter realised a scene that Walpole had imbued with abundant descriptive detail, although the architecture, as typical throughout Otranto, is not defined. The passage in Otranto, of which Carter was clearly aware, suggests around 523 characters in Frederick’s retinue, and it is worth quoting the text in full to contextualise Carter’s vivid rendition of the scene:

The prince, in the mean time, had passed into the court, and ordered the gates of the castle to be flung open for the reception of the stranger knight and his train. In a few minutes the cavalcade arrived. First came two harbingers with wands. Next a herald, followed by two pages and two trumpets. Then an hundred foot-guards. They were attended by as many horse. After them fifty guards. Footmen, clothed in scarlet and black, the colours of the knight. Then a led horse. Two heralds on each side of a gentleman on horseback bearing a banner with the arms of Vicenza and Otranto quarterly – a circumstance that much offended Manfred – but he stifled his resentment. Two more pages. The knight’s confessor telling his beads. Fifty more footmen, clad as before. Two knights habited in complete armour, their beavers down, comrades to the principal knight. The ’squires of the two knights, carrying their shields and devices. The knight’s own ’squire. An hundred gentlemen bearing an enormous sword, and seeming to faint under the weight of it. The knight himself on a chestnut steed, in complete armour, his lance in the rest, his face entirely concealed by his visor, which was surmounted by a large plume of scarlet and black feathers. Fifty foot-guards with drums and trumpets closed the procession, which wheeled off to the right and left to make room for the principal knight.

As soon as he approached the gate, he stopped; and the herald advancing, read again the words of the challenge. Manfred’s eyes were fixed on the gigantic sword, and he scarce seemed to attend to the cartel: but his attention was soon diverted by a tempest of wind that rose behind him. He turned, and beheld the plumes of the enchanted helmet agitated in the same extraordinary manner as before.Footnote 43

The gigantic sword with its bearers (though far short of Walpole’s one hundred) – along with the heralds, knights, horses and attendant parts of the train – are admirably illustrated by Carter. En masse, they convey fully the pomp and circumstance of the scene. And Manfred’s affront to the scene – the usurpation of his station and title, Prince of Otranto – is equally captured. In particular, in the prospect behind Manfred’s left shoulder, we see the arms of Vicenza and Otranto quartered – indicating Frederick’s apparently legitimate dominion over Manfred’s castle and land (fig 8). Vicenza’s arms, that of a golden Lion of St Mark (for Venice), is a natural choice on Carter’s behalf, and Otranto’s arms is a subtle modification of those of Naples under the Angevins. This corresponds with Otranto’s setting and conceivably demonstrates Carter’s researches into, and awareness of, the novel’s purported age (the time of the Crusades) and of heraldry more broadly.

Fig 8 John Carter, detail of The Entry of Frederick into the Castle of Otranto, 1790, showing the portraits of John Carter and Horace Walpole and the back-to-front quartered arms of Vicenza and Otranto. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 790.00.00.138dr+)

Subverting this historical awareness and his attention to detail, the architectural setting is not real: instead, at best, Carter loosely paraphrases building types and styles. The Perpendicular structure to the rear right of the courtyard responds loosely to the western facades of Bath Abbey and Winchester Cathedral, while not being either in the fine detail. The cross towering over the scene is loosely based upon that at Winchester, though, once again, modified: none of these architectural models have anything to do with the novel. Besides, Perpendicular Gothic architecture post-dates the supposed age of Otranto by a century, and is therefore surprisingly anachronistic given Carter’s heraldic research and otherwise robust attention to detail. This anachronism does not, however, disrupt Otranto’s narrative; instead, it creates a striking High Gothic context that is consistent with his other elaborate works discussed here.

Carter exploited the language of heraldry to great effect. He dots the arms of Otranto (Naples) across the painting, including on the entrance tower, the shield, banners and flags in the foreground, and the heralds’ tabards and flags in the middle-ground. This gesture, however, was not without error – the quartered arms of Vicenza and Otranto that enraged Manfred so much in the novel, depicted behind him and Isabella, shows the flag’s reverse side; here, the arms face as they would on the obverse, meaning that the Lion of St Mark is mirrored the wrong way. There is no firm explanation for this oversight: Carter may have simply made a mistake, though this is unlikely given the effort expended planning and executing the watercolour’s minute details. Perhaps it is a subtle indication of the invalidity of Frederick’s claim to the title of Otranto, which is an important element in the Otranto narrative. Despite the uncertainty surrounding this heraldic component, the scene in general celebrates the forms, motifs and styles of medieval architecture that the ‘heretical part’ of Walpole’s heart adored.Footnote 44 It also weaves in the heraldic details pertinent to Otranto’s narrative, by which Walpole was fascinated, harnessing it at Strawberry Hill, as he did, to create a visual representation of his pedigree, particularly in the armoury on the staircase, and on the library’s ceiling.Footnote 45 Moreover, as indicated in the passage quoted above, heraldry certainly guided Frederick’s reception by Manfred, the then apparent Prince of Otranto.

Aside from the style of the architecture, the deployment of heraldry and the fact that Walpole purchased it and hung it in his Gothic villa, The Entry of Frederick has little to do with Strawberry Hill. And yet, two figures in the lower right-hand corner of this watercolour are particularly unusual, and serve to link the scene with the eighteenth century. The person directly behind Manfred and Isabella looks out confrontationally at the viewer. This is almost certainly a self-portrait of Carter: the face correlates with the self-portrait (c 1817) produced with Sylvester Harding, now in the British Museum, and with another included in the frontispiece to his Occurrences; his attributes – the beret and roll of paper – support his identity as architect, draughtsman and artist.Footnote 46 The second figure, in the bottom right-hand corner talking to a page, is almost certainly Walpole himself. The face and hair, quite distinct, like Carter’s, from the remainder of the watercolour’s caricature-like representations, matches Walpole’s appearance as recorded by Carter in his Three sketches of Horace Walpole in 1788 and the portrait (1796) by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830).Footnote 47

The Carter self-portrait was previously thought by W S Lewis to depict Walpole. This in part governed the price he was willing to pay to acquire the work from General Sir Henry Cholmondeley Jackson in 1962. ‘Because of its Strawberry Hill provenance plus the HW portrait,’ he wrote, ‘I do not think £500 is excessive.’Footnote 48 His letter does not identify where Walpole is within the crowd; however, correspondence between Lewis and Sir Owen Morshead written ten days earlier furnishes the essential information, including the portrait’s ‘discovery’: Morshead recounts that the General ‘loathe[s] the whole notion of taking money for the drawing at all – which has acquired all the more value to me through Mr. Lewis’s discovery that the figure is H.W. himself’.Footnote 49 Importantly, Morshead found the General ‘aglow at having just discovered [within the watercolour] a quite unmistakable Devil (with 2 horns) at the right-hand margin, apparently glaring towards H.W.’.Footnote 50

Lewis later published this identification in his co-authored ‘The portraits of Horace Walpole’.Footnote 51 Walpole is almost certainly in the picture; however, the figure to the left of the ‘Devil’ is more likely to be Carter, whose confrontational gaze announces, in line with an established tradition in European art, the importance of his architectural genius and skill as a draughtsman. Carter is more prominent because he converted Walpole’s words to line, colour and shade. Walpole, if this reading is correct, is below, and to the right of, Carter. His importance to the form and appearance of The Entry of Frederick is subsidiary to Carter’s architectural vision. Walpole is nevertheless intimately associated with the narrative – as indicated already, this scene is one of the most prominent expressions of medieval spectacle in Otranto. Carter demonstrates Walpole’s authorial responsibility for the novel, but takes for himself the credit of interpreting and visualising the literary work. These portraits are, effectively, signatures that would have been instantly recognisable to Walpole, Carter and their circle of antiquarian friends.

Of course, this identification may appear hopeful and speculative – the hair, for example, is, after all, of a generically eighteenth-century style and form. However, Carter’s second illustration of Otranto depicting the death of Matilda (fig 9), and the related frontispiece to Specimens of Ancient Sculpture (1780) (see fig 7), suggest otherwise.Footnote 52 Walpole’s personal coat of arms was differentiated from that of the Earl of Orford (Or on a Fess between two Chevrons Sable three Crosses Crosslet of the Field) by the addition of a sable mullet under the upper chevron’s apex. He used it as the centrepiece to the heraldic scheme applied to the library ceiling at Strawberry Hill; it was stamped on the boards of books in his collection and also used on his bookplate (fig 10). John Chute (1701–76), one of the members of Walpole’s Strawberry Committee whom he termed ‘my Oracle of taste’, also applied elements from the differentiated arms onto a proposed facade for the cottage in the grounds of Strawberry Hill.Footnote 53 Carter similarly harnessed Walpole’s personal arms, including them together with the Saracen’s head – the Walpole family crest – at the foot of the tomb-chest in the frontispiece to the first volume of Specimens of Ancient Sculpture (1780) (fig 11). Carter’s initial watercolour proposal for the frontispiece did not include Walpole’s arms, but instead another, though visually related, coat mostly hidden behind figures.Footnote 54 By removing the figures obscuring the arms in the engraving, and by changing the armorial to Walpole’s personal, differentiated form, Carter visually reiterated the volume’s dedication to Walpole, albeit simultaneously by suggesting that Walpole lived and died in the Middle Ages.Footnote 55 Including a portrait of Walpole in The Entry of Frederik is, therefore, consistent with this earlier engraving as a dedicatory signpost to the man himself.

Fig 9 John Carter, The Death of Matilda, c 1780. Photograph: courtesy of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London (RIBA SB52/5)

Fig 10 Walpole’s personally differentiated arms: a bookplate pasted into the title page of the manuscript of ‘The English baronage from William I to James I’, after 1763. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, 49 3499)

Fig 11 John Carter, Specimens of Ancient Sculpture and Painting (1780): detail of the frontispiece. Photograph: courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University (LWL, Folio 46 780C)

The second monumental watercolour by Carter illustrating Otranto depicts the death of Matilda (see fig 9), and builds upon the imagery already considered, including The Entry of Frederick and the frontispiece to the first volume of Specimens of Ancient Sculpture.Footnote 56 Like the frontispiece, it includes Walpole’s personally distinguished arms; but, instead of incorporating it once, Carter inserts it, on this occasion, in places: on a boss, above the high altar, at the end of the tomb and on its prie dieu in the foreground, on the front board of the Bible, on a side altar, and on another two tombs in the background. Walpole, and anyone familiar with Walpole’s personal coat of arms, would have understood this reference immediately: Walpole’s hand cannot be separated from the form, context and appearance of Otranto.

Carter, as with The Entry of Frederick, does not indicate Strawberry Hill’s role in the narrative – none of the tombs illustrated here, for example, were by Walpole to create Strawberry Hill’s interior, a fact of which Carter, having delineated the house, would no doubt have been aware. Instead, the very fabric of Otranto’s physical manifestation celebrates and dilates Walpoleian architectural associations writ large. Matilda’s murder in the church of St Nicholas, adjacent to the castle of Otranto, consequently takes place in what is effectively Carter’s reinterpretation of Walpole’s private Gothic chapel-cum-cathedral, realised on a scale grander than anything that Walpole ever achieved in reality: at Strawberry Hill, with The Castle of Otranto, or, indeed, at any other house, such as Lee Priory, Kent (1785), that emerged from Walpole’s circle.Footnote 57 Walpole’s arms is the most frequently displayed in the scene: Otranto’s arms, for example, appears only six times in the illustration, and therefore is secondary to Walpole’s own. It is, perhaps, a little ironic, however, that Carter decided to place Walpole’s personal variation of his family arms on three separate tombs; the idea, nevertheless, is direct. Despite this intriguing decision, Carter’s drawings of Otranto and the related frontispiece for Specimens of Ancient Sculpture are the most compelling and extraordinarily complex historicist essays in late Georgian Britain equal to and excelling the engravings circulated by the Boydell Gallery, such as John Ogborne’s engraving after Josiah Boydell depicting Henry VI, Part I, Act ii, Scene iv (1790–5), and King Richard the Second, Act v, Scene ii, The Entrance of King Richard & Bolingbroke into London, by Robert Thew after James Northcote (1801) (fig 12).Footnote 58

Fig 12 The Entrance of King Richard & Bolingbroke into London, from Shakespeare’s King Richard the Second, Act v, Scene ii (1801), Robert Thew (engraver), after James Northcote. Photograph: courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, Yale University (YCBA, B1977.14.20007)

It is clear from these three illustrations that Carter was, simultaneously, informed, imaginative and visually articulate. His use of heraldry, much like Walpole’s interest in the subject matter, was fundamental to his realisation of Otranto’s narrative, and through this he established Otranto’s relationship with Walpole. Heraldry is a coded language, and the clear and repeated use of Walpole’s personal arms emphasised his status as the true author and inspiration behind these works. Carter’s architectural quotations, such as the near-exact reproduction of the tomb of Aymer de Valance, Earl of Pembroke, Westminster Abbey, in the background of The Death of Matilda would have carried favour in Walpole’s circle, and certainly corresponds with Walpole’s own recycling of medieval tombs for domestic design purposes at Strawberry Hill. These representations of Otranto’s scenes, much like the frontispieces to Specimens of Ancient Sculpture, are hyperbolic and unnecessarily grand: while Walpole never indicates the castle’s dimensions, he never implies that it is on the scale depicted in Carter’s watercolours. St Nicholas, for example, is generally referred to as a church, although, on one occasion, Walpole calls it a cathedral.Footnote 59 Carter certainly managed to capitalise upon this continuity error, and the setting for The Death of Matilda was designed to impress: its form, decoration and atmosphere were clearly indebted to Carter’s love and passionate defence of medieval architecture.Footnote 60

Curiously, just over a decade after Carter had completed these watercolours, and following the death of Walpole in 1797, he turned on the late 4th Earl of Orford, his one-time patron. Writing in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1801 under the heading of ‘The pursuits of architectural innovation’, Carter spent the majority of the article critiquing Wren’s work: for example, the great modern monument of classical architecture, St Paul’s Cathedral, London, whose design ‘in the Corinthian taste being then thought to “exceed the splendour and magnificence of the old cathedral when in its best state”’.Footnote 61 However, in the same piece, Carter considers the contentious topic of ‘Gothic architecture revived’, a tendency, he continues, which has ‘within these few years been banded about the kingdom, and some of its dregs we find foisted on our sight, as the fronts of the courts in Westminster hall’ by William Kent.Footnote 62 Carter continues by claiming that:

This half-and-half, this ‘fire-and-water’ mixture, this Gothic and Roman compound of all that is new and strange, may still further be pursued; and we, looking through comparisons perspective, may just take a glimpse at Strawberry-hill. And if a correspondent is to be believed in his account of the abbey at Fonthill … we may also there see this unaccountable combination carried to the utmost pitch of human gratification; where we find ‘a noble Gothic arch’ (if we are to judge from the annexed view) is but a ‘hole in the wall,’ an ‘abbey’ without an abbot.Footnote 63

After Walpole’s death, Carter criticised Walpole’s Gothic villa, a house that he had recorded in such painstaking detail in an extra-illustrated copy of the Description of the Villa of Mr. Horace Walpole (Reference Walpole1784) thirteen years before. And yet, during Walpole’s lifetime, Carter was happy to accept the patronage of a fellow admirer of medieval architecture. Indeed, in a previously unknown record he made of Walpole’s Chapel in the Woods in 1787, Very slight View of the Gothic chapel, which contains the Shrine of Sr. in the garden at Strawberry Hill, Carter overtly praises its fidelity to medieval architecture: ‘(This Chapel was Copied and executed with the utmost nicety and truth in Portland stone from part of the Dudley chapel, in the choir of Salisbury Cathedral, by Mr. Gafere Mason, Westminster)’.Footnote 64 Like Walpole, who felt that Strawberry Hill was but ‘a sketch by beginners’, whose early parts had been designed and realised by his ‘workmen who had not studied the science [of Gothic design]’, Carter was certainly aware of Strawberry Hill’s flaws as a piece of Gothic architecture.Footnote 65 He, nevertheless, appears pragmatic: Walpole was a friend and client who was equally enamoured with the medieval past, and alienating him would have been counterproductive. Despite this later criticism, their shared passion for the medieval period precipitated overtly reverential watercolours designed to recognise and flatter Walpole’s role as author of Otranto and as a prominent supporter of the Gothic past.

Acknowledgements

This short article is the result of an interest in Strawberry Hill, Horace Walpole and The Castle of Otranto cultivated during my doctoral studies at the University of St Andrews. Fiona Robertson, Horace Walpole Professor of English Literature, encouraged me to think about Otranto and its depictions in greater detail. It is because of her encouragement that I formulated this piece in late 2015. I am further indebted to Fiona and also to Dale Townshend, who, together, supported my fellowship application to the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, to work on a project exploring the visualisation of Otranto. I was honoured to become a repeat Fellow at the Lewis Walpole Library, and without it I could not have developed this interpretation of Carter and Greathead Jr’s illustrations. I can only express my gratitude to all the staff at the Lewis Walpole Library, in particular Nicole Bouché, Cindy Roman, Sue Walker, Kristen McDonald and Scott Poglitsch. They offered unstinting support throughout my residence in Farmington, and not once did they bat an eyelid despite my library record frequently having twenty copies of Otranto on request at any one time. I was also privileged to have ready access to Carter’s Entry of Frederick for the entire duration of my fellowship. Dale Townshend has offered helpful comments regarding the article’s analysis of Otranto and its related watercolours. The time and opportunity afforded me to work on this project as part of my AHRC-funded postdoctoral research fellowship at the University of Stirling is most welcome. Finally, I would like to thank the peer reviewers for their thoughts and suggestions regarding the essay’s argument.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

BL British Library, London

BM British Museum, London

KCL King’s College Archives, London

LWL Lewis Walpole Library, Farmington, CT

NPG National Portrait Gallery, London

RIBA Royal Institute of British Architects, London

SH Strawberry Hill

YCBA Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT