The study of medieval commemorative carvings has moved in recent years from a focus on the major effigial monuments to consideration of ‘lesser’ monuments, incised stones and cross slabs. The studies of F A Greenhill considered both incised effigial monuments and the more elaborate incised crosses.Footnote 1 Lawrence Butler and Colin Gresham pioneered the study of the simpler cross slabs in the 1950s and 1960s,Footnote 2 and their work has been followed up more recently by Peter Ryder, Brian and Moira Gittos and Aleksandra McClain.Footnote 3 Nevertheless, cross slabs could be still described as the unsung heroes of medieval commemoration.

If medieval cross slabs are the unsung heroes, post-medieval cross slabs are the unknown warriors. Nigel Llewellyn’s Funeral Monuments in Post-Reformation England makes brief reference to ledgerstones and cheaper forms of commemoration, but cross slabs do not feature at all.Footnote 4 Butler mentions a post-Reformation cross slab of c 1600 at Baswich, Staffordshire,Footnote 5 but his studies identify a tailing-off in numbers from the end of the fourteenth century. Distribution tables in Ryder and McClain suggest a similar decline in numbers. Ryder felt that ‘one or two’ of his Northumberland cross slabs might be post-Reformation in date,Footnote 6 but that in West Yorkshire ‘[p]roduction of cross slabs … ceased in the sixteenth century’.Footnote 7 The incised wall slab commemorating Guy Carleton (d. 1628) and his sister’s children at Holy Trinity Church, Cuckfield, West Sussex, has as part of its decoration a rather schematic anchor (which is almost a cross) with the words Crux Christi Anchor Spe incised on it as a subsidiary part of a decorative scheme including some other ‘Arminian’ iconography (a cherub and a burning heart).Footnote 8 Discussion with several Fellows has, however, suggested that cross slabs are assumed to be an almost entirely pre-Reformation phenomenon, with a very few exceptions.

This may be, to some extent, a self-fulfilling assumption; there is a strongly regional element in the typologies of medieval incised slabs of all kinds, and, in the absence of identifiable inscriptions, dating will always involve an element of guesswork. It does, however, present a problem to historians and archaeologists in south-east Wales, where clearly datable post-Reformation cross slabs occur in some numbers. Field survey has so far identified about 150, and there are doubtless more to be found (figs 1 and 2). A recent visit to Abergavenny, when furniture had been moved for building work, resulted in the identification of an additional two cross slabs (and a possible third) in a church that has already been extensively surveyed. Brecon Cathedral has around sixty (it is difficult to give an exact figure because so much of the church is carpeted). Llanilltud Fawr (Llantwit Major, Glamorgan) has at least sixteen, plus some that might be reused medieval stones, and an unknowable number beneath pews and decking. There are significant collections at churches as widely spread as Abergavenny and Llangattock-nigh-Usk (both in Monmouthshire)Footnote 9 and Llandow (Glamorgan), and smaller collections and single examples in churches and churchyards throughout the region. This is clearly too large an area for the work of one workshop and there are, indeed, several distinct styles, from the very plain crosses that predominate in the Vale of Glamorgan to the ornate cross heads, baroque scrolled bases and subsidiary vernacular figures of north Monmouthshire. Some of these are datable stylistically and some by their inscriptions.

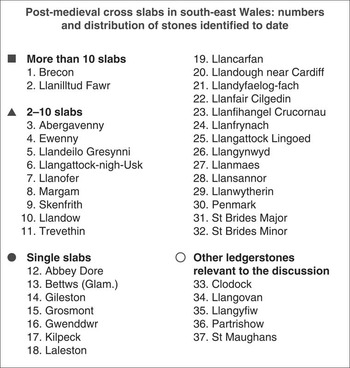

Fig 1 Distribution of late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cross slabs in south-east Wales and the Marches. Drawing: Ann Leaver

Fig 2 Numbered list of churches with late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cross slabs and related carvings

It is always possible that, in some cases, these are medieval stones that have been recut with later inscriptions. Initially this was assumed to be the case with a cross slab at Llandyfaelog-fach, Breconshire, where the inscription round the edge of the slab commemorating Thomas, son of Watkin ab Owain (who died in the second decade of the seventeenth century – part of the date is missing), slightly cuts into the cross head. However, the design of the cross head, with its baroque-style squared fleur-de-lis finials, is markedly different from medieval floriated cross heads and is very similar to cross heads from more securely dated seventeenth-century examples in Brecon Cathedral, where the inscriptions are clearly part of the original design. More likely to have been recut from a medieval original is the stone just west of the chancel steps in Llanilltud Fawr, which now bears the inscription ‘WILLIAM THOMAS / 1602 / MARGARET YORETH / THE LATE WIFE OF / MORGAN THOMAS / 1625’. The inscription lies awkwardly over the cross, which is a plain Calvary cross (with a stepped base, generally assumed to have been modelled on altar crosses) with slender shafts and simple fleur-de-lis finials. The slab tapers slightly, but not enough to suggest an early date, and is probably late medieval. A stone in the churchyard at Llanfair Cilgedin, Monmouthshire, is more puzzling (fig 3). Drawn by Bradney in 1906, it has a floriated head, which could be late medieval or early post-medieval.Footnote 10 Two S-shaped decorations flow out from the shaft; these again could indicate either date. The base is a cruder form of the baroque scrolled design found on seventeenth-century memorials in north Monmouthshire. The slab has clearly been reused; the inscription is inverted and reads ‘WT W / AETATIS 78 / SEPULT 7 III NOVEMBR …’ (the rest of the figures were indecipherable when Bradney saw it; the whole is now even more difficult to read). This could be a reused medieval slab, but the design of the base makes it more likely that this is a post-medieval slab that has been recut with a later inscription.

Fig 3 Floriated cross in the churchyard at Llanfair Cilgedin, Monmouthshire (Bradney Reference Badham and Norris1906, 414)

Reuse of medieval cross slabs is significant in itself, as Sarah Tarlow has pointed out in the context of reused cross slabs in Orkney.Footnote 11 Some of her examples of reuse, she suggests, could be intended to preserve important memorials and offer evidence of ‘an adherence to Catholic values and practices’. In most cases, however, she concludes that those who preserved and adapted pre-Reformation memorials would not have considered themselves Catholic; rather, they were loyal but traditionalist members of the Reformed Church, unwilling to give up on traditions they valued.

Further confusion can be caused by the recutting of cross slabs that are probably post-medieval in origin. Just inside the south door at Skenfrith, Monmouthshire, is a ledgerstone commemorating a Charles Edwards who died in the eighteenth century (the date seems never to have been completed). The slab has a cross head of seventeenth-century design, much more heavily worn than the inscription. It looks very much as though a seventeenth-century stone has been recut in the early eighteenth. Several of the very plain cross slabs at Llanilltud Fawr have also been recut, in one case as late as 1795.Footnote 12

Ironically, some of these post-medieval memorials were included in two of the earliest studies to focus primarily on cross slabs. In an article published in the Transactions of the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society in 1904, the Welsh antiquary and polymath T H Thomas provided fairly rough line drawings of twenty-five cross slabs, most of them from Glamorgan, two from Monmouthshire and one from Hanmer in north-east Wales.Footnote 13 He was mainly interested in Calvary crosses, though he also included drawings of a few crosses with different styles of bases. Thomas assumed, on the basis of surviving inscriptions, that most of these crosses dated from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, though many of them have subsequently been re-dated to the medieval period; the inscriptions are evidence of reuse. However, a number of the south Wales cross slabs in his study are clearly post-medieval, and the Hanmer example may have been so. This slab was seen by Thomas Dineley in 1684 (fig 4). Thomas seems to have redrawn it from Dineley’s sketch rather than inspecting it himself. It can no longer be found and was probably destroyed in the fire that virtually destroyed Hanmer church in 1889. It was idiosyncratic in design and the decoration had clearly been recut at some point. When Dineley saw it, it bore the inscription ‘IE 1608’.Footnote 14 From Dineley’s drawing, Thomas thought the initials and date were integral to the design, but they may have been a later addition.

Fig 4 Thomas Dineley’s drawing of a cross slab in Hanmer, Flintshire (Dineley Reference Bradney1888, 99)

Thomas’s study was followed up with a further article in the Transactions of the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society in 1911 by another architect, John Rodger.Footnote 15 Rodger cast the net rather wider than Thomas, recording several cross slabs in Breconshire, though he did not include the Hanmer example. His drawings were much more accurate and meticulously measured, and he illustrated 125 cross slabs, ranging in date from the eleventh to the eighteenth centuries. Of these, more than thirty are almost certainly post-medieval, and a couple more may be post-medieval or may have been recut. Many of the stones drawn by Thomas and Rodger are now more worn than they were a century ago, so their work is a valuable guide. Little or nothing has been done since to follow up the avenues opened in these two articles, and they remain the foundation for any desk-top survey of the subject.

The post-medieval cross slabs in both these studies are mainly from the Vale of Glamorgan and the area immediately to the west, around Margam. Between them, Rodger and Thomas identified most of the surviving slabs in that area, though there are a few more to be added to the corpus. They show at least three distinct designs: two found throughout the Vale of Glamorgan and the third found to the west at Bettws and Margam. The simplest, found at Gileston, Llancarfan, and Llandough, near Cardiff, as well as numerous examples at Llanilltud Fawr, is a very plain four-line design, usually with a three-step Calvary base, though bases range from one to four steps (fig 5).

Fig 5 The simplest cross slabs, in the Vale of Glamorgan (Rodger Reference Parry1911, 48)

Llanilltud Fawr also has several examples of a clearly different design: a plain cross with thick arms and shaft, sometimes slightly splayed, with raised panels at the sides (Thomas and Rodger describe these as ‘billets’) and a rectangular base (fig 6). This seems to have been intended to provide space for an inscription, though not all the stones actually have lettering. One of the stones in this style at Gileston, commemorating members of the Giles family who died in the early seventeenth century, has shields on the rectangular base carved with the family arms (one with cross crosslets in saltire, the other with a chevron between three crowns) (fig 7).Footnote 16 Other examples of this style can be found at Ewenny, Laleston, Llandow, Llanmaes, Llansannor, Penmark, St Brides Major and St Brides Minor, several of them with shields, but none with carved heraldry (they were probably painted).

Fig 6 Different styles of billeted crosses (Rodger Reference Parry1911, 57)

Fig 7 The Giles family monument at Gileston, Glamorgan, with shields and IHS trigram. Photograph: author

Slabs with designs somewhere between these two, with a thick-armed cross flanked by billets, but on a conventional Calvary base and with the inscription round the edge of the stone, can also be found throughout the region; there are several examples at Llandow and one miniature stone commemorating a Mary Powel, who died in 1671, at Llangynwyd in the uplands of the Llynfi valley. At Bettws, and further west at Margam, are stones with decoration on the rectangular bases of the crosses (fig 8). These could possibly be late medieval, and the two at Margam now underlie the early seventeenth-century alabaster tomb chests of the Mansel family, but the style of the crosses is very similar to other examples that are clearly post-medieval.

Fig 8 Billeted cross with decorated base at Margam, Glamorgan. Photograph: author

The diversity of designs makes it clear that we are dealing with several stonemasons’ workshops offering a range of options. Where the dates on these Glamorgan slabs are legible, they are mainly from the seventeenth century. There is, however, one very early plain cross at Llanilltud Fawr, commemorating a Mathew Voss who died in 1534 (his age is given as 129: the first digit is carved quite clearly and seems unlikely to be a flaw in the stone). We might here have the origin of the very plain four-line design of some of these crosses.

Thomas and Rodger both speculated about the origins and meanings of some of the designs on these post-medieval slabs. Thomas was particularly interested in the low relief billets. He and Rodger thought these might derive from the design of some very unusual triple crosses that they identified at Margam, Laleston and Llangynwyd. Rodger thought the triple crosses were reminiscent of continental Calvaries depicting Mary and John as well as the crucified Christ, but poetic evidence suggests that the Glamorgan examples were intended to represent the two thieves as well as Christ.Footnote 17 While the full-scale triple crosses are almost certainly medieval, the billets on the post-medieval ones may embody a reflection of the medieval Crucifixion scene and the importance of the good thief in the ars moriendi tradition. At Bettws, Margam and St Brides Major the billets are accompanied by small rosettes or crosses, either in the angles of the cross arms or half way down the billets. These might be purely decorative, but they might also have a vestigial symbolic function; the circular designs, for example, may be a reflection of the depiction of the sun and moon to either side in several medieval Crucifixion scenes.

While most of the surviving crosses simply record the names and family connections of the deceased, the simplicity of the crosses and the design of the panels gave scope for more complicated inscriptions. A stone just inside the south door at Llancarfan commemorates a Robert David who died in 1628. It has been recut with the letters ‘WR’ and ‘75’, then with a couple of lines of verse:

[MY HOPE] ON CHRIST

[IS FI]XED SURE

WHO WOUNDED

WAS MY WOUNDS

TO CURE W R

and the date ‘169[…]’. This poem is most famous in the version on a seventeenth-century window in the Victoria and Albert Museum. According to tradition it came from Carisbrooke Castle and was scratched by Charles i when he was a prisoner there.Footnote 18 The poem appears in several variants on other seventeenth-century gravestones; the earliest is possibly the fuller version on the monument of Thomas Urquhart of Kinundie, in Ross and Cromarty:

My hope shall never be confounded,

Because on Christ my hope is grounded,

My hope on Christ is rested sure,

Who wounded was my wounds to cure;

Grieve not when friends and kinsfolk die,

They gain by death eternity.Footnote 19

Thomas Urquhart died in 1633, so his monument pre-dates Charles i’s captivity at Carisbrooke. Wales was predominantly Royalist in the Civil War and conservative in sympathies after the Restoration. However, while it is possible that WR (whoever he or she was) knew about the poem’s connection with Charles i, it is perhaps more likely that the poem was simply chosen as being suitable for a memorial. Like the cross design, the emphasis on the Wounds of Christ is probably evidence not of Catholic sympathies but of traditionalism; it even anticipates the focus on the Wounds in much English and Welsh Methodist hymn writing.

While Thomas and Rodger between them drew most of the post-medieval cross slabs in Glamorgan, their coverage of Monmouthshire and Breconshire was much more sparse. Thomas drew two stones at Trevethin, the old parish church of what is now Pontypool, which may be post-medieval. One has a cross head with fleur-de-lis finials that could be sixteenth-century and a curved base that has some similarities to the scrolled bases of the north Gwent crosses. The inscription reads ‘EVN JO DD THE 6TH FEB 1665’. Much of this inscription has now spalled off. The other slab drawn by Thomas is no longer visible. His drawing shows a cross that has lost its head, but that has a curved base identical to the first and miniature crosses on either side of the shaft; the inscription reads ‘1695 WW’. However, Thomas missed another fragmentary cross, currently partly obscured by panelling. All that can be seen is a very worn fragment of a scrolled base and a recut inscription recording a David Williams with a date of death in the eighteenth century.

The much more elaborate post-medieval incised cross slabs of northern Monmouthshire are largely unrecorded, though a few appear in Joseph Bradney’s History of Monmouthshire. Typically, these crosses have intricately floriated heads and elegant scrolled bases. Examples can be found at Abergavenny, Llangattock Lingoed, Llangattock-nigh-Usk, Llanwytherin and Skenfrith, and there are three of varying design in the churchyard at Llanofer. As well as some more elaborate complete stones, the church at Llangattock-nigh-Usk has a number of fragments of cross head and scrolled bases. At Abergavenny and Llangattock Lingoed, some of the crosses are flanked by naive figures in early seventeenth-century costume (figs 9 and 10). A slightly different style of cross at Llanfihangel Crucornau and Llandeilo Gresynni has smaller heads, Calvary bases and larger flanking figures. Again, they seem to be the work of several groups of stonemasons. There are also stones with similar figures but no cross head (the Williams and Baker-Gabb memorial at Grosmont is a striking example). Clearly clients could choose from a range of options.

Fig 9 Reused monument in Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, with IHS trigram in the floriated cross head, small flanking vernacular figures and scrolled base. Photograph: author

Fig 10 Llangattock Lingoed, Monmouthshire: cross with small interlaced head, large flanking figures and scrolled base. Photograph: author

Few of these stones have much in the way of inscriptions; some have no surviving lettering and most have only initials. However, one stone at Abergavenny has a lengthy inscription in Latin:

Scio quod redemptor meus vivit: Iob 19.2

Guliel’ Williams fil’ primogenitus Ricei Williams armigeri de Park Lettice defunct’, postquam 70 annos Christi non sine char[itate] complevisset, plac[ate] in Domino obdormiv[it] 9o die Novemb’ Ann. 1633 et hic sepultus, cui una cum sanct’ omnibus defunctis consummationem in die novissimo con[cedat] Deus per merita Iesu amen Footnote 20

This inscription could be translated in two ways. The opening is clear enough:

I know that my Redeemer liveth: Job 19:2

William Williams, first-born son of Rice Williams, esquire, of Park Lettice, deceased, after that he had completed 70 years, not without the love of Christ, gently fell asleep in the Lord on the 9th day of November in the year 1633, and is buried here

But should we translate cui una cum sanct’ omnibus defunctis consummationem in die novissimo concedat Deus as ‘to whom with all the holy dead may God grant the consummation in the last day’ or ‘to whom with all the departed saints’? The first is good Prayer Book English, ‘blessed are the dead which die in the Lord’. The second is dangerously close to Catholic veneration of the saints.

The choice of Latin could be perceived as having Roman Catholic undertones,Footnote 21 though it could also be used to indicate learning, being the language of the intellectual mainstream.Footnote 22 It was also the language of choice for the memorials of many of the London civic elite.Footnote 23 It was perfectly legitimate for the tomb of an Oxford-educated cleric. The incised effigial slab of Herbert Jones, rector of Llangattock-nigh-Usk from 1614 until his death in 1644, has a lengthy and consciously loyalist inscription describing him as Minister pacificus & fidelis, Qui Deo, Regi & Patriae gratissimus in Christo feliciter obdormavit (‘a peaceful and faithful Minister, who, pleasing to God, King and Country, fell peacefully asleep’).Footnote 24

A range of slightly different styles is found in Breconshire. Surviving examples are mainly confined to the church of St John the Evangelist on the outskirts of the old town of Brecon, now Brecon Cathedral, though they appear as far north as Gwenddwr, near Builth. The cross slabs in Brecon Cathedral were largely relocated during the restoration by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the 1860s and 1870s, and many of them survive only in fragmented form, having been trimmed to fit their present locations. Most of them have cross heads with squared baroque fleur-de-lis finials. The shaft is, in effect, a division between the panels of inscription; usually in false-relief capitals, these record the names of the children as well as of the deceased. Some have occupational emblems. Shears are incised on a cross slab that lies between the crossing and the south transept. The name of the deceased is missing, but the names of the surviving children can still be read: ‘HAD ISSUE 8 CHILDREN NOW LIVING 4 IOHN LYKY GWENLLIAN AND ELIZABETH’. Shears also appear on the cross slab in the south transept of Jeffrey Johnes, tailor, who died in 1618 (fig 11). His slab is also decorated with the lamb and flag, another emblem with Catholic connotations, but one that was widely used by the Arminian tendency in the Established Church. Occupational emblems were common on medieval cross slabs in the Midlands and the north of England but were always unusual in Wales, though Brecon has a few medieval examples.

Fig 11 Brecon Cathedral: monument to Jeffrey Johnes, tailor (d. 1618), with shears, lamb and flag. Photograph: author

The false-relief capitals of the Breconshire slabs are reminiscent of the Lombardic capitals on the medieval slabs from north Wales studied by Gresham. Virtually all the slabs from Monmouthshire and Glamorgan have incised Roman capitals (cut with varying degrees of skill), though a few of the earlier ones have inscriptions in blackletter and one in Abergavenny has false-relief capitals in the ‘Breconshire’ style (fig 12).Footnote 25 Nigel Llewellyn suggests that the choice of Roman capitals for effigial monuments may have had connotations of degree, but that there is no evidence that it showed awareness of Renaissance styles and ideas.Footnote 26 As far as the ledgerstones are concerned, the fashion for Roman capitals appears to have reached the Vale of Glamorgan surprisingly early (the 1534 memorial to Mathew Voss at Llanilltud Fawr has admittedly crude incised capitals) and to have spread to Monmouthshire and south Breconshire by the end of the sixteenth century.

Fig 12 Abergavenny, Monmouthshire: monument to ‘Edward …’. Simple cross, IHS trigram, inscription in raised capitals. Photograph: Nathan Clements and Rhys James

Brecon also has several examples of another feature of these post-medieval cross slabs. In Brecon and in north Monmouthshire, several (though not all) of the cross slabs have the IHS trigram carved in the centre of the cross head. The trigram is commonplace on later medieval tombs; there are examples across south Wales, including an early sixteenth-century one now in the cathedral museum at Brecon. These reflect the popularity of the late medieval cult of the Holy Name of Jesus. Devotion to the Holy Name was rooted in the Bible and early Christianity; popularised by such mystics as the fourteenth-century hermit and writer, Richard Rolle, and the fifteenth-century Franciscan preacher, Bernardino of Siena, it was a key element in late medieval devotional practice.Footnote 27 Lutton suggests it was ‘particularly malleable to “moderate Protestant” as well as Catholic reshaping’.Footnote 28 There was certainly nothing in devotion to the Holy Name that was fundamentally antithetical to Reformed thinking. Calvin encouraged Christians to ‘glorify His Holy Name with our whole life’.Footnote 29 In his Treatise on Good Works, Luther encouraged his readers (with a multiplicity of Biblical references) to ‘call upon God’s name in every need … he teaches and compels us to honour and call upon his name, to gain confidence and faith in him, and so fulfil the first two commandments’.Footnote 30 The feast of the Holy Name was included in the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer (and thence in the Welsh Llyfr Gweddi Gyffredin). As Susan Wabuda has suggested, the visual depiction of the trigram ‘incorporated an advantageous measure of abstraction, which appealed to Protestants needy of visual representation but wary of Catholic idolatry’.Footnote 31 By the same token, moderate Protestants accepted the use of illustrations in editions of the Bible, but replaced depictions of God the Father with the Tetragrammaton, the Hebrew letters YHWH for the name of God.Footnote 32 Like other visual imagery, however, both the IHS trigram and the Tetragrammaton were regarded by many reformers as suspect. The altar cloth at Canterbury Cathedral, with its Tetragrammaton embroidered in gold on silver, was said to ‘to usher in the breaden God of Rome and idolatry’ by Richard Culmer, the Kentish minister, in 1641.Footnote 33

On all the medieval tombs, the trigram is carved in blackletter script. What distinguishes the post-medieval examples is that the trigram is in square Roman capitals. There are some pre-Reformation examples of the use of Roman capitals – for example, in Jacopo Bellini’s 1450s panel painting of Bernardino of Siena, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.Footnote 34 Wynkyn de Worde used the Roman capital style set in a Tudor rose in his 1522 edition of Lady Margaret Beaufort’s The Mirroure of Golde for the Synfull Soule.Footnote 35 The earliest English tomb-carving of this version seems to be the 1533 brass of William Wardyworth at Betchworth, Surrey, which shows him vested for mass and carrying an unusually large chalice and wafer with the trigram.Footnote 36 The brass of Anne Fermor at St Mary the Virgin, Easton Neston, Northamptonshire, has a tablet hanging from her waist with the trigram in square capitals (and this at the height of the Edwardian Reformation), though the slightly later brasses of Elizabeth Cave (1558) at St Laurence, Chicheley, Buckinghamshire, and Jane Seymour (c 1565) at St Martin, Fivehead, Somerset, are in the blackletter style (this last is the latest example of the blackletter style that Hugo Blake and his colleagues could find in the early modern period).Footnote 37

On the one hand, the depiction of the trigram in Roman capitals seems to have been regarded as less ‘popish’ than the blackletter version. On the other, the version in Roman capitals with the cross sitting on the bar of the H was the one adopted by Ignatius Loyola as part of the emblem of his Society of Jesus. Most of the Monmouthshire and Breconshire cross slabs with the IHS trigram are within easy reach of the Jesuit college at the Cwm in Llanrothal, just across the Monnow in Herefordshire, and it is hard to believe that those who commissioned the carvings would have been unaware of the Society’s emblem. By the end of the sixteenth century it was being identified both with the Jesuits and with more widespread expressions of post-Tridentine Catholic piety.Footnote 38 William Dowsing’s deputy, Francis Jessup, certainly described it as ‘IHS the Jesuit’s badge’.Footnote 39

However, the IHS trigram appeared in a number of contexts in early seventeenth-century England and Wales. Some of these were clearly Catholic. Thomas Tresham famously decorated his triangular lodge at Rushton, Northamptonshire, with the core Jesuit emblem of the trigram and three nails. Some of the jewellery and mass plate described by Hugo Blake and his colleagues also appears to have been recusant in origin, though the trigram also featured on communion plate for the Established Church.Footnote 40 Some of the earlier examples (in blackletter) are clearly reused from pre-Reformation plate. At St Clement’s, Rowston, Lincolnshire, the paten was reused as a cover with its central IHS design cut out, but at Chattisham, Suffolk, the IHS was inset into the foot of the paten-cover and at Fitz, Shropshire, a panel with the IHS trigram was reset in the base of the communion cup and roughly scored with the date 1565.Footnote 41 By that date some plate can also be found with the trigram in the Roman capitals form, though one has to be careful with dating; in many cases the trigram is clearly in a much later style and has been added to an earlier cup. St Lawrence’s, Stoak, Cheshire, had an Elizabethan communion cup, the work of William Mutton of Chester. Now in the Grosvenor Museum in Chester, it has the trigram in a sunburst, almost certainly added in 1772 when the church was given a paten and flagon also engraved with the trigram.Footnote 42 Lightbown suggested that the trigram could have been more acceptable on early seventeenth-century communion plate because it was ‘a formula expressly to render Christ by letters, rather than by a figure’.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, there are rather more (and more securely dated) surviving examples from the post-Restoration period.Footnote 44

In the wake of the seventeenth-century religious movement variously described as Laudian, Arminian and High Anglican (none of these descriptions is really adequate), visual decoration in general, and the IHS trigram in particular, became more common in the Established Church.Footnote 45 IHS emblems can still be seen in the early seventeenth-century painted glass at St Katherine Cree in London. The glass with a similar design at St Giles in the Fields was presumably lost when the church was rebuilt in the 1730s, but was described by Munday in his (1633) continuation of Stow’s Survey of London.Footnote 46 The device would have been at its most conspicuous on Inigo Jones’s original design for the new west front of St Paul’s (though this was eventually superseded by a magnificent portico funded by Charles i).Footnote 47 These were emphatically Anglican contexts, though in some cases they pre-date the period properly described as ‘Laudian’. There was nevertheless some suspicion of such decorations as tending to popery, and in the 1640s determined efforts were made to eradicate them. In 1616 a London goldsmith gave a pulpit cloth decorated with the trigram to the church of St Bartholomew Exchange. It was apparently accepted with no opposition, and was even approved by the minister there, the puritan Dr Robert Hill, but in 1643 the parishioners described the letters as ‘popish’ and demanded they be removed. Merritt suggests that the problem was precisely that the Laudians had subsequently attributed religious significance to the device, so Puritans could no longer regard it as ‘indifferent’.Footnote 48 The trigram on the altar cloth at Anstie, Hertfordshire, was described in 1641 as ‘the Jesuit’s badge’ and a similar altarback at St Giles in the Fields, London, was accused of having ‘popish’ connotations and being part of a ‘Romish’ move towards ritualism.Footnote 49

The earliest of the post-Reformation IHS cross slabs in south-east Wales is at Llangattock-nigh-Usk (fig 13). The original inscription on the slab commemorates an Owen Lawrence, probably the man of that name who was alive in 1552; the shaft of the cross has been replaced by inscriptions commemorating members of the Lewis family in the early eighteenth century.Footnote 50 Recorded by Bradney in 1906, it was probably originally inside the church, but was outside the east end when Bradney saw it. It is still there; it has suffered considerable weathering and has recently been broken across.Footnote 51

Fig 13 Rubbing of slab at Llangattock-nigh-Usk commemorating Owen Lawrence and members of the Lewis family (Bradney Reference Badham and Norris1906, facing p 349)

The IHS emblem also appears on several stones at Abergavenny (including the Williams cross slab with the Latin inscription described above), at Llandeilo Gresynni and Llanwytherin and on a particularly elaborate cross with hearts and flowers at Skenfrith commemorating a ‘…s’ [possibly Charles] Walker; the date is unfortunately missing. These stones are similar in style to the other north Monmouthshire cross slabs, suggesting that the addition of the IHS trigram was a matter of personal choice.

Not all the IHS inscribed stones also have crosses. The trigram in square capitals continued as a popular decorative emblem on monuments into the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; from the mid-nineteenth century, under the influence of the Oxford Movement, the blackletter version again became the norm. There are, however, no datable cross slabs after the late seventeenth century. Even before that, not all IHS slabs had crosses. A couple of stones at Partrishow (Breconshire) and Llangyfiw (Monmouthshire) have elegant scrolled designs with fleurs-de-lis and the trigram.Footnote 52 The Partrishow stone is dated March 1688, a time when Catholics were certainly in the ascendant. The Llangyfiw stone is as near to a cross as can be without actually being one; it bears the date 1651 (inverted, at the base, this could be a later addition as 1651 is perhaps the most unlikely of all dates for a public display of the trigram) and the initials ‘W’ and ‘EC’. A minor stonemasons’ workshop can be identified in the St Maughans area of north-east Monmouthshire, just west of Monmouth. Exploiting the mudstone slabs of the St Maughans Formation, they produced ledgerstones with crude lettering, IHS emblems and other simpler decorative devices, including stylised flowers and fleurs-de-lis, a heart and a very crudely carved face. One at St Maughans itself, dated 1723, has the IHS trigram in a heart surmounted by a small cross, but this is the cross as part of the IHS emblem, not a cross slab. Several of the IHS stones have seventeenth-century dates; it seems that this was the preferred style of the workshop, possibly (to judge by the crudity of the carving and the poor lettering) because they lacked the skill to produce the very elaborate crosses typical of other workshops in the area.

Evidence of changing fashions (and possibly of uneasiness at the use of cross slabs and the IHS trigram) is found on a stone at Grosmont, Monmouthshire. When an eighteenth-century memorial to the Springet family was taken up for conservation and repositioning on the wall of the north transept, a visitor to the church noticed carving on the reverse. This, it emerged, was a baroque cross with the IHS emblem in the centre of the cross head. The cross head is an accomplished piece of carving, but the scrolled base is only roughly incised. There is no inscription. Unfortunately, by the time the significance of this unfinished carving was realised, the slab had been firmly fixed to the wall with the Springet memorial facing outwards. Fortunately, the church visitor had photographed the carving on the reverse so a record of it has been made.

We can only speculate about the reason for the unfinished appearance of the incised cross. The family could have decided on a change of design for practical reasons – money, possibly, or a wish for a design that would allow for a fuller inscription. Alternatively, Grosmont lies less than ten miles from the famous seventeenth-century Jesuit college at the Cwm in Llanrothal, just across the River Monnow, in Herefordshire. Catholics in the area were hunted and persecuted in the aftermath of the ‘Popish Plot’ crisis in 1678. The cross slab could well date from that period and it is possible that whoever commissioned it felt compelled to abandon the design in the context of an upsurge in anti-Catholic feeling. The stone would then have remained in the workshop and would have been available for reuse. The inscription on the reverse (the side now visible) is clearly of two dates. The first, in typical late seventeenth- / early eighteenth-century capitals, commemorates a Thomas Springet who was buried in 1689. The second, in Roman and italic script, commemorates James Springet (d. 1726). It is not impossible that the stone could have been abandoned in the wake of the ‘Popish Plot’ and reused a little over a decade later.

But are these designs evidence of Catholic sympathy? Like the IHS trigram, the cross was compatible with the Christocentric tendency and the concentration on Christ’s redemptive sacrifice in earlier and more moderate Protestantism. Catherine Parr, sixth wife of Henry viii, and usually considered a devout reformer, described the Crucifix (not the Crucifixion but its visual representation) as ‘the book, wherein God hath included all things, and hath most compendiously written therein … let us endeavour ourselves to study this book’.Footnote 53 Nevertheless (again like the trigram), visual representation of the Crucifixion, even in the abstracted designs usual on cross slabs, became increasingly suspect. The memorial to Edward Hunter (d. 1646) at Marholm, Northamptonshire, actually has the lines:

Noe crucifix you see, noe Frightfull Brand

Of Superstition’s here. Pray let me stand.Footnote 54

Ironically, by the later seventeenth century in New England, the Puritans had become more relaxed about funeral customs and commemoration; there are examples of crosses on coffins in Massachusetts as well as on tombstones.Footnote 55 It is also worth remembering that tombs were explicitly excluded from Commonwealth ordinances for the removal of crucifixes, crosses and other visual imagery in churches.Footnote 56

In his study of the seventeenth-century monuments of Co Kilkenny, Paul Cockerham assumes that the continued use of cross slabs in Ireland was linked to Catholicism.Footnote 57 Some of the Welsh cross slabs can certainly be linked to families with Catholic tendencies. A slab now in the vestry of the church at Gwenddwr, Breconshire, commemorates Bodenham Gunter, who died in 1686. He appeared in the 1680 list of Breconshire Catholics presented to the House of Lords.Footnote 58 It is also possible that an incomplete cross slab now in the north chapel at St Mary’s, Abergavenny (but clearly relocated as it now has the head to the east), commemorates a member of a Catholic family. The slab is inscribed with the IHS trigram, the initials ‘RG’ and the date 1672. It is possible that this stone commemorates one of the Gunters, Abergavenny’s leading Catholic family in the later seventeenth century, though the family’s pedigrees do not suggest an obvious candidate.

Rather more difficult to pin down is a slab partly concealed by the panelling in the Havard Chapel in Brecon Cathedral (fig 14). A floriated cross with heraldic shields on either side of the shaft, it has the inscription (in false-relief blackletter) Hic sepultus est Lodovicus Havarde generosus qui obiit octodecimo die mensis Octobris 1569 cujus anime propitietur Deus. Both the use of Latin and the veiled prayer for his soul (‘on whose soul my God have mercy’) could be seen as a challenge to the Established Church. According to Theophilus Jones, Hugh Thomas recorded a very similar stone commemorating Edward Games and located under the high altar of the church, with the inscription Hic sepultus erat doctissimus EDVARDUS GAMES armiger legum peritus et pater patriae qui obiit 1564, Die 9 Septembris, cujus anime propicietur Deus. This stone was no longer there when Jones was writing in 1809.Footnote 59 There are no overtly Catholic sentiments on the Glamorgan slabs, though the claim that ‘God hath his soule to save’ on a 1586 slab at Llantrithyd (the name has unfortunately been broken off) could be read as a prayer, and there are a few Latin inscriptions.

Fig 14 Monument to Lewis Havard in Brecon Cathedral (Jones Reference Haigh1809, facing p 20)

The antiquary John Weever expressed concern that inscriptions including the phrase orate pro anima or concluding cuius animae propitietur Deus were particularly vulnerable to iconoclastic attack.Footnote 60 The use of Latin, too, may have been suspected of concealing deviancy in doctrine.Footnote 61 Both the Havards and the Gameses were accused of Catholic sympathies in the later sixteenth century, though in the case of the Games family this may have had more to do with local politics than religious belief.Footnote 62 The Havards of the Senni valley were certainly loyal to the Catholic faith in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, the fact that both men seem to have opted for burial in St John’s suggests that they saw themselves as members of the Established Church. Both died, of course, before the issuing of the bull Regnans in Excelsis in 1570, which attempted to put an end to the slippery process of compromise.

Other cross slabs, though, have explicit statements of loyalism. A battered slab in St Keyne’s Chapel, in Brecon Cathedral, commemorates a Richard John William, who married Gwladis, daughter of Phillip Price (fig 15). The slab has an elaborately interlaced and floriated cross head and the words ‘Honour the King’; the first part of the quote from 1 Peter 2: 17, ‘Fear God’, has spalled off. So, unfortunately, has the last digit of the date. Richard John William died in the 1620s, but it is impossible to link his memorial conclusively with William Laud’s tenure of the diocese of St Davids from 1621 to 1626. What this tombstone and others like it suggest, though, is that Laud’s combination of ceremonialism and loyalism would have found a congenial home in south Wales.

Fig 15 Monument to Richard John William in Brecon Cathedral. Elaborate cross head with IHS trigram and ‘Honour the King’ below. Photograph: author

Members of the clergy and their families were also commemorated by cross slabs. A stone in the south-west corner of the eastern church at Llanilltud Fawr was initially installed to commemorate Catherine, wife of the vicar Stephen Slugge. She died in 1626. The shaft of the cross was then shaved off and an inscription added commemorating Stephen Slugge himself, who died in 1662 aged eighty-two, with the word Resurgam (‘I shall rise again’). Finally, a stone immediately north of this one commemorates Stephen’s second wife Elisabeth, who died in 1676. The second stone has the Latin inscription Disce mori mundo et vivere disce deo (‘Learn to die in the world, and learn to live in God’). The lettering all but obliterates the cross on this slab and it may be yet another example of reuse of a post-medieval slab (fig 16). The most complete example of the ‘Jesuit’ style of IHS trigram is on a slab between the chancel and the Havard Chapel in Brecon Cathedral. Instead of a cross head, this has the IHS trigram and a heart pierced by three nails, all set in a sunburst (fig 17). But this slab (not technically a cross slab, though the sunburst is very like the head of a cross) commemorates Anne Bulcott, daughter of Lewis Morgan who was vicar of Brecon in 1621–33. She married Thomas, son of Roger Bulcott, who died in 1659.Footnote 63 The Bulcotts of Defynnog and Aberyscir were Catholics, but the Brecon branch of the family does not appear to have shared their religious standpoint, and Anne and Thomas’s son, Charles, was High Sheriff in 1679.Footnote 64 Family responses to religious change can be complex and difficult to disentangle. The tomb of Sir Edward Saunders (d. 1573) at Weston-under-Wetherley, Warwickshire, has a Latin inscription and panels depicting the Resurrection and Ascension, but Saunders’ brother was a Protestant martyr.Footnote 65

Fig 16 The Slugge family monuments at Llanilltud Fawr, Glamorgan. Some billeted crosses can be seen to the left. Photograph: author

Fig 17 The Jesuit emblem (IHS trigram, heart pierced with nails in sunburst) on the monument of Alice Bulcott in Brecon Cathedral. Photograph: author

Hugo Blake’s point that ‘[i]t is difficult to determine whether early seventeenth-century material decorated with the trigram was used by an Arminian revivalist or by a Catholic recusant’ could equally well be applied to these cross slabs, though the continuing use of cross slabs through the later part of the sixteenth century suggests that we are looking not at revival but at survival.Footnote 66 Other ‘Jesuit’ emblems were also part of the visual vocabulary of the early seventeenth-century ritualists. Like Anne Bulcott’s tomb, the roof panels of John Cosin’s chapel at Peterhouse College, Cambridge, are decorated with the sunburst. Cosin also used the sunburst and another Jesuit emblem, the flaming heart, as well as the trigram, on the title page of his A Collection of Private Devotions.Footnote 67

Elucidating the background to these monuments requires an exploration of some new thinking on the history of religion in Wales in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The underlying problem (with which generations of Welsh historians have struggled) is that, while there is little or no evidence of discontent or desire for reform in the early sixteenth century, there is also little evidence for overt resistance thereafter. While there is evidence throughout Wales for the survival of traditional beliefs and practices, these were seldom seen as a challenge to secular authority.

The traditional interpretation of the surviving cross slabs (still to be found in many church guide books) is that they commemorate recusant Catholics. The areas covered by this study – southern Glamorgan, northern Monmouthshire and south Breconshire – were clearly heartlands of Catholic recusancy. Catholicism has been described as the ‘nonconformism of the gentry’,Footnote 68 and Monmouthshire was said to be ‘stuffed with Papists … who possess plenty of arms and money’,Footnote 69 but Robert Matthews’ work on the Monmouthshire Catholics suggests that this is an illusion created by a few high-profile examples.Footnote 70 Most of the Catholics in Monmouthshire came from families of very minor gentry, yeomen and artisans. The Breconshire Catholics have not been studied in the same detail, but the work of R Tudur Jones and Michael Lewis suggests a similar picture.Footnote 71 Lists of early seventeenth-century Brecon recusants in the State Papers describe a few of them as ‘of great abilities and possessions’, but others are ‘of a verie poore estate … now verie poore … a poore labouringe man’ and in most cases there is no attempt to assess their means.Footnote 72 However, while it was precisely the minor gentry, yeomen and urban craftsmen who were most likely to be commemorated by ledgerstones, it is impossible to link most of the names in the lists of recusants with the names on the cross slabs.

The whole issue of Catholic burial is fraught with uncertainty. On the one hand, Catholics were sometimes warned not to seek burial in Protestant churches,Footnote 73 while Protestant clergy were intermittently instructed not to bury known Catholics.Footnote 74 On the other hand, many open Catholics asked for and were able to secure burial in the churchyard and even in the parish church.Footnote 75 It was even possible for wealthy and powerful Catholics to use their local influence to insist on inscriptions asking for mercy on the souls of the departed.Footnote 76 Attempts to bury Catholics in consecrated ground could result in local disputes; it was one such at Allensmore, just over the border into Herefordshire, which sparked the Catholic protests known as the ‘Whitsun Riots’ in 1605.Footnote 77 There is little evidence for such disputes in Wales: Kate Olson has described the ‘complex mix of accommodation, realism, and social, local and familial allegiances’ that constrained both burial choices and community responses.Footnote 78 Nevertheless, it still seems unlikely that openly recusant Catholics could have been buried inside churches in such large numbers with flagrantly Catholic symbols on their tombs.

While the recusants of Monmouthshire and Breconshire have been the focus of much historical enquiry, they were never that numerous: Matthews’ figures suggest that they never amounted to more than 6 per cent of the population of Monmouthshire. Open recusancy is, however, only part of the story of Catholic resistance. There was an unknowable number of fellow-travellers, ‘church papists’, who (in defiance of papal injunction) attended church and held their own beliefs in private. There was an even more ill-defined layer, a ‘sympathetic penumbra’, of landowners and magistrates who were not prepared to prosecute Catholics with any vigour.Footnote 79 But although Wales was notoriously conservative in religious belief and practice in this period, it was not in general a conservatism that challenged the secular state. Bishops complained repeatedly about the condition of their dioceses. In 1567 the new Bishop of Bangor, Nicholas Robinson, reported to the Privy Council that his diocese was still largely unreformed:

[I]gnorance contineweth many in the dregges of superstition … Images and aulters standing in churches undefaced, lewde and undecent vigils and watches observed, much pilgramegegoying, many candels sett up to the honour of sainctes, some reliquies yet caried about and all the cuntreis full of bedes and knottes …Footnote 80

Similar complaints were made by Richard Davies and Hugh Middleton, successive bishops of St Davids (the diocese which covered Brecon).Footnote 81

For all this fondness for ‘bedes and knottes’, however, Wales did not offer any serious opposition to the Established Church. Hugh Jones, Bishop of Llandaff 1566–74, was probably more in line with the Privy Council’s thinking. His report in 1570 gave plenty of information on the problems of his diocese – the shortage of qualified preachers, the diversion of financial resources by lay impropriators and the Crown – but as far as the laity were concerned, he reported that all was well.Footnote 82 Jones has been criticised for this omnia bene return in a diocese where recusancy was later to be such a problem, but it is worth remembering that he was not asked to ‘make windows into men’s souls’ but to report ‘concerninge the state of religion and conformytye of the people within my dyocese of Landaff, both for resortinge to theire parishe churches to the common prayers and receavinge of the hollye sacramentes at usuall tymes’. As far as the Privy Council was concerned, it seems that if people were attending church regularly and communicating occasionally, all was indeed well.

Kate Olson discusses this very complex situation in terms of negotiation, accommodation and pragmatism.Footnote 83 It may not even have been as conscious as that; there was a stubborn traditionalism that was in no way incompatible with loyalism. Sarah Tarlow suggests that the same combination of loyalism and traditionalism may explain the passive resistance and adherence to traditional customs in Orkney:

These acts were not an organized campaign, not an expression of anti-Protestantism. We see in post-Reformation religious practices something far less strategic – a ‘getting on with things’.Footnote 84

We should beware of the temptation to put the people of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into neat little boxes according to their ostensible religious standpoints. Confessional identities were not monolithic, and confessional boundaries were, as Raymond Gillespie has pointed out, ‘negotiable and even permeable’,Footnote 85 but more than that, we should not assume that people defined themselves in confessional terms. It was quite possible to welcome the Bible in Welsh, communion in both kinds and the legalisation of clerical marriage and to consider oneself a loyal member of the Established Church while rejecting the theology of predestination, liking candles and bells, still valuing the intercession of the saints and the power of holy wells – and seeing nothing wrong with having crosses and the Holy Name of Jesus on memorials to the dead.

The final puzzle is the fact that, with very few exceptions, these stones are only found in south-east Wales. There are a few just over the border into Herefordshire, in the Welsh-speaking hundred of Ergyng or Archenfield. The border here is a construct, dating only from the sixteenth-century Acts of Union, and one would not expect it to mark a cultural frontier. Nevertheless, post-medieval cross slabs are much more unusual to the east of this arbitrary line on the map. Enquiry of historians, diocesan archaeologists and fellow members of the Church Monuments Society has not produced any definite information on late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cross slabs outside this area.

Of all the churches in the border country where one might have expected to find traditional symbols, the most likely is surely Abbey Dore, Sir John Scudamore’s impeccably Laudian church created out of the ruined abbey chancel. Indeed, there is a cross slab there, albeit a rather idiosyncratic one. Commemorating a Robert William, who died in 1696, and recut for a Philip Williams, who died in 1729, it has a rather rococo cross head set at the base of the stone, under the inscription, and a border with swags of foliage and flowers that looks forward to the work of the Brute family of stonemasons. Also at Abbey Dore, a heavy medieval coffin-shaped slab with a small cross pattée has been recut with an inscription to ‘P P 1757’. At nearby Kilpeck there is a stone with a very plain cross commemorating Bridgit Gomond (d. 1685) and her husband Edmund (d. 1713). Nearer still to the Welsh border, at Clodock, is an even more idiosyncratic stone commemorating a Lewis Philip with the recut date 1676. This stone has at the head the trigram, a fleur-de-lis and a heart, and the inscription Beati ab hoc tempore mortui ii, qui Domini causa moriuntur (‘Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord’, a quote from the funeral service in the Book of Common Prayer, though the choice of Latin may be significant). At the base of the stone are two six-spoked wheels and a strange little figure.

Jonathan Finch’s study of church monuments in Norfolk straddles the Reformation divide.Footnote 86 He has confirmed the absence of post-Reformation cross slabs in the county and made the illuminating suggestion that the continuing popularity of cross slabs in south-east Wales may be linked to the fact that there are so few medieval brasses in the region.Footnote 87 This begs the question why there were so few brasses, but that is material for another paper.Footnote 88 If stone slabs remained in use until the Reformation, the conservatism of Welsh society in the early modern period might explain their continuation afterwards. This is certainly borne out by the design of the very simple crosses in the Vale of Glamorgan. The earliest of these is dated 1534, and suggests a continuity of use through the changes of the sixteenth century. In general, the design of crosses became simpler towards the end of the medieval period, suggesting that what we have here is a ‘trickle-down’ model of material culture, with designs being simplified for use by slightly lower strata of society.

This does not, however, explain why the post-medieval cross slabs seem confined to the south and east of Wales. The stone at Hanmer drawn by Dineley and T H Thomas is the only documented example in the north east of the country. There are examples of reuse of medieval cross slabs (as at Caerwys, in Flintshire), and a particularly interesting stone in the churchyard of Henllan, in Denbighshire, has a Latin inscription in raised Lombardic capitals clearly modelled on medieval examples, but impeccably Protestant in its sentiments. Nevertheless, while the present study cannot claim to be exhaustive, field survey for a database of medieval tomb carvings in Wales has involved visiting most Welsh churches with early fabric and no further post-medieval cross slabs have been identified. Enquiry of the archaeological trusts and diocesan archaeologists has also failed to produce any more references. If ledgerstones in the north and west have any decoration, it is usually heraldic or some form of memento mori design; there are also a few with hearts. One stone in Beaumaris, Anglesey, seems to reflect the same tradition as the cross slabs. In an extremely vulnerable position just west of the chancel steps, it could have been calculated to attract maximum footfall. The inscription (in raised Lombardic capitals) is now virtually illegible, but in 1937 the RCAHMW read it as commemorating a Richard Brice and suggested a date in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries.Footnote 89 The epigraphy and the style suggest a seventeenth-century date rather than eighteenth. The stone is dominated by a shield including the arms of the Cusack family, but at the head are most of the Instruments of the Passion: the palm leaf of the Entry into Jerusalem, the cockerel on the column, the crown of thorns, the ladder, hammer and pincers, the three nails set in a heart, the seamless robe and the spear. Accompanying these is the IHS trigram with a cross on the bar of the H (fig 18). The people of Beaumaris had been accused of participating in traditional funeral practices in 1570; a corpse was buried there with candles and singing of psalms. The bishop, Nicholas Robinson, was prepared to accept that this had been done out of ignorance, but he forced the mayor and his colleagues to admit it was ‘a folishe custome there used’, implying it was normal practice in the area.Footnote 90

Fig 18 The Instruments of the Passion and the IHS trigram on a ledgerstone in Beaumaris, Anglesey. Photograph: author

The Beaumaris slab does not really count as a cross slab, and very few post-medieval cross slabs have as yet been identified outside south-east Wales and the border. The area covered by IHS emblems on cross slabs is even smaller, with none identified outside Brecon and northern Monmouthshire apart from one outlier at Gileston in the Vale of Glamorgan. (Later versions of the trigram without cross slabs are much more common.) One other feature, which may be significant, is that the cross slabs only appear on ledgerstones; there are plenty of seventeenth-century wall memorials, but as far as we can see there are none with crosses. (The IHS trigram does appear later on wall monuments as well as on later ledgerstones.) Carved stones were not the cheapest form of memorial. Nigel Llewellyn has pointed to the increasing popularity of painted wall panels in the early modern period,Footnote 91 and the Post-Reformation Wall Painting Project has identified commemorative wall paintings from the same period.Footnote 92 Study of these simplest of memorials, even more vulnerable than ledgerstones, is still in its infancy.

South-east Wales was regarded as a heartland of popery, but the proportion of overt Catholics was small. There were other pockets of Catholic resistance in the north, but, similar to the recusants of Monmouthshire and Breconshire, they have probably received more attention than their numbers would warrant. If stubborn traditionalism rather than overt recusancy is the explanation for the survival of so many ‘Catholic’ practices across Wales, it is hard to see why it should not also have led to the survival of the cross-slab style of commemoration elsewhere in the country, especially in north-east Wales where there was such a long tradition of elaborately carved medieval slabs.

The answer may lie in the very local nature of fashions in material culture at the social level of those who would be commemorated by a ledger stone rather than a chest tomb or wall monument. More work needs to be done on these unobtrusive but illuminating memorials to elucidate changing patterns in fashion and in the nature of workshops. The work of the Ledgerstones Survey is beginning to fill out the picture, aided by NADFAS surveys. In Wales, for example, NADFAS has recently undertaken a survey of the ledgerstones in the Havard Chapel of Brecon Cathedral as part of a more general survey of the chapel. It is hoped that this will encourage detailed survey of the rest of the former priory church, which, according to Brian and Moira Gittos, has one of the best collections of seventeenth-century ledgerstones in the UK.Footnote 93 Ledgerstones are the most acutely vulnerable of any church monuments: at risk from erosion, but very difficult to protect. As churches are encouraged to install heating, damp-proofing and toilet facilities, more stones are likely to be moved. Displacing them inevitably blurs their significance, but it may (as in the case of the Grosmont slab) lead to new discoveries. There is always an upside.

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefited from discussion at several conferences, including the Cambrian Archaeological Association’s annual conference at Llangollen in 2014. I am grateful to the Journal’s peer reviewers for their helpful suggestions, which have clarified and strengthened the argument. I am also grateful to several Fellows – notably Thomas Lloyd and Fr Jerome Bertram – for information on the IHS trigram on tombs and church plate; to Rosamund Rocyn Jones for drawing my attention to the Grosmont slab, which first alerted me to the post-Reformation cross slabs of south-east Wales, and for discussing the elaborate north Gwent slabs with me; to Rachel Duthie of Brecon Cathedral for sharing her knowledge of the building’s memorials; to the members of numerous local historical societies who have pointed me in the direction of further examples; and to the incumbents and churchwardens who have kindly opened churches for me (I am particularly grateful to those church communities who keep their buildings open so that we can explore them without complicated forward planning). Finally, I am grateful to Ann Leaver who drew the map and helped with the other illustrations.