Thomas Lyte (1568–1638),Footnote 1 of Lytes Cary, Somerset, is associated with two remarkable artefacts from the court of James i. The first of these is the Lyte Genealogy (fig 1), an illustrated pedigree tracing the descent of James i from Brutus, which Lyte presented to the king at Whitehall in 1610; the second is the Lyte Jewel (fig 2), a diamond-studded locket containing a miniature of James i by Nicholas Hilliard, which the king gave to Lyte in 1610–11. The Jewel was given to the British Museum as part of the Waddesdon Bequest in 1898, while the Genealogy was bought by the British Museum in 1964 and is now in the British Library. More recently, they were brought to wider public attention when they featured in the exhibition Shakespeare: Staging the World at the British Museum in 2012,Footnote 2 and in the BBC television series The King and the Playwright: a Jacobean history, presented by Professor James Shapiro, in the same year.

Fig 1 Central panel of the Lyte Genealogy (BL, Add ms 48343). Photograph: © The British Library Board

Fig 2 The Lyte Jewel, enamelled gold set with diamonds with a miniature of James vi of Scotland and James i of England, London, 1610–11 (BM, WB.167). Photographs: © Trustees of the British Museum; all rights reserved

In the course of research for the British Museum’s Shakespeare exhibition it became apparent that these two objects needed to be reassessed – and, what is more, reassessed together. Each is remarkable in its own right, but together they form part of a connected story about Jacobean court culture and the public representation of kingship. The balance of value in the exchange might seem inequitable, since the Genealogy has often been regarded as a minor antiquarian curiosity, whereas the Jewel has long been recognised as one of the finest pieces of jewellery to survive from the early Stuart period. In the first and second sections of this article we show why Thomas Lyte was so richly rewarded for his labours, by setting the Genealogy in the context of contemporary debates on the Anglo-Scottish union and the Stuart succession. In the third section we show how the Lyte Jewel belongs to a culture of lavish royal gift-giving at the Jacobean court, and offer new evidence to strengthen its attribution to George Heriot, the king’s jeweller.

THOMAS LYTE AND THE GENEALOGY

Thomas Lyte inherited his antiquarian interests from his father, Henry Lyte (1529–1607), who had the reputation of being ‘a most excellent scholar in several sorts of learning’.Footnote 3 Henry Lyte (fig 3) is best known for his translation of Dodoens’ New Herball, or Historie of Plantes (1578), a landmark work in the history of English botany. His copy of the 1557 French Dodoens, now in the British Library, is inscribed ‘Henry Lyte taught me to speake Englishe’ and is heavily annotated in red and black ink, with further notes added by Thomas, including a list of the fruit trees in the orchard at Lytes Cary.Footnote 4 The house at Lytes Cary, now in the possession of the National Trust, later fell into dereliction before being restored in the early twentieth century, but enough remains of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century decorative schemes to show that, like other gentry houses of the same period, it was richly decorated with heraldic stained glass and painted coats of arms.Footnote 5 Thomas Lyte’s papers also include an inventory of the muniments at Lytes Cary, a substantial collection of deeds, rolls and other documents stored in an assortment of iron chests, wooden boxes and wicker hampers in the ‘closet’, possibly the room now known as the Little Parlour.Footnote 6 The visitor to Lytes Cary would thus have been confronted with a powerful visual assertion of the family’s right to gentry status, with the documentary evidence to back it up. This was the setting in which the Lyte Genealogy would once have been displayed.

Fig 3 Thomas Lyte’s portrait of his father Henry Lyte, c 1633 (SRO, DD/X/LY/2). Photograph: Somerset Record Office

Henry Lyte’s only appearance in print, apart from his translation of Dodoens, was a short historical treatise, The Light of Brittaine, which he presented to Elizabeth i on the occasion of her triumphal procession to St Paul’s Cathedral on 24 November 1588 following the defeat of the Spanish Armada. In this work he traced the history of Britain back to its mythical foundation by the Trojan prince Brute, and argued that many of the great noble families of England, including the Grays, the Percys, the Cecils and the Sydneys, were descended from Brute’s Trojan followers.Footnote 7 The Brute legend was especially important to Lyte as a means of upholding the honour and dignity of his own family; in an unpublished manuscript treatise he argued that the Lytes were descended from Leitus, one of the five captains of Brute’s army, and that the Lyte coat of arms (gules, a chevron between three swans argent) was based on the standard carried by Leitus at the siege of Troy. Lyte believed that the towns of Bruton and Castle Cary had both been established by the Trojans, the former named after Brute himself, the latter after Caria in Asia Minor, and that the proximity of Lytes Cary to these two ancient settlements ‘provethe that we were not only of Brutes trayne, but also somwhat neare aboute him’.Footnote 8

This fanciful theory led T D Kendrick to characterise Lyte as the epitome of the old-fashioned ‘fundamentalist’ antiquary, in opposition to the new ‘sceptical modernist’ school pioneered by William Camden.Footnote 9 Yet, this is an over-simplification. Lyte could hardly remain untouched by the pervasive influence of Camden’s Britannia, and his annotated copy of the book shows how closely he studied it.Footnote 10 Although he took issue with Camden over his rejection of the Brutus legend, he was clearly influenced both by Camden’s model of topographical or chorographical history (which, as Jan Broadway has recently argued, provided a pattern, on a national scale, that local antiquaries could apply to the history of their own family or county) and by his method of using the etymology of place-names to reconstruct their history.Footnote 11 Thomas Lyte was on friendly terms with Camden, who wrote some Latin verses in commendation of the Genealogy and added a note to the English translation of Britannia in 1610 praising Lyte as ‘a gentleman studious of all good knowledge’.Footnote 12 Lyte in his turn acted as a mentor to other local antiquaries, such as Thomas Gerard, whose Particular Description of the County of Somerset (1633) acknowledged ‘his love to my own studie’ and ‘his great humanitie towards mee in helping mee with many excellent peices of evidence and other antiquities which have bin very useful unto mee’.Footnote 13

The Lyte Genealogy was probably begun soon after James’s accession in 1603, as a companion manuscript, ‘Britaines Monarchie’, bears the colophon: ‘Dedicated to his excellent Maiestie and published with his royall assent and Priviledge, 1605’.Footnote 14 It was most probably a collaborative project, started by Henry Lyte and completed by Thomas after his father’s death in 1607. Thomas’s inventory of his papers includes ‘A petigree from Brute drawne by my father in a little Roll’, which may refer to an early draft of the Genealogy.Footnote 15 The final version was presented to James at Whitehall on 12 July 1610, in the presence of Prince Henry, Archbishop Bancroft and the Earls of Salisbury, Northampton, Nottingham, Arundel, Southampton and Montgomery.Footnote 16 The first published reference to it occurs in Anthony Munday’s historical compendium, A Briefe Chronicle of the Successe of Times (1611), which prints a lengthy extract from Henry Lyte’s The Light of Brittaine in defence of the Brutus legend, ending as follows:

Thus much out of Maister Lytes Light of Brittaine, which worthy Gentleman being deceased, his Son Maister Thomas Lyte, of Lytescarie, Esquire, a true immitator and heyre to his Fathers Vertues, hath (not long since) presented the Maiesty of King Iames, with an excellent Mappe or Genealogicall Table (containing the bredth and circumference of twenty large sheets of Paper) which he entitled Brittaines Monarchy, approuing Brutes History, and the whole succession of this our Nation, from the very Original, with the iust observation of al times, changes and occasions therein happening. This worthy worke, having cost above seaven yeares labour, besides great charges and expence, his highnesse hath made very gratious acceptance of, and to witnesse the same, in Court it hangeth in an especiall place of eminence.Footnote 17

Munday expresses the hope that the Genealogy might be ‘made more generall’, adding that ‘his Maiesty hath graunted him priviledge, so, that the world might be worthie to enioy it, whereto, if friendship may prevaile, as he hath bin already, so shall he be still as earnestly sollicited’. This seems to suggest that Lyte was planning an engraved version of the Genealogy. No such engraving is now known to survive, but a copy was later in the possession of William Aubrey, brother of the antiquary John Aubrey, who called it ‘bigger than the biggest map of the world I ever sawe’.Footnote 18 Thomas Hearne also saw a copy which he described as ‘ingraved in about 20 sheets of Paper to be pasted together and hung up’, though he added that it was ‘wonderful scarce’.Footnote 19

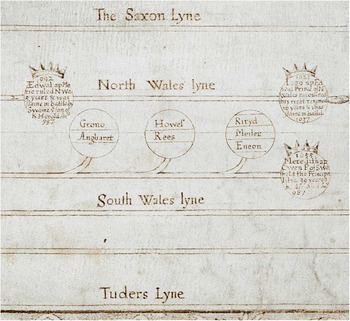

The copy of the Genealogy that was presented to the king, ‘fairlye written in Parchment and set fourth in rich coulers in a verie large Table’, no longer survives, having perhaps been destroyed in the Whitehall Palace fire of 1619. What remains is the uncoloured copy in pen and ink that belonged to Thomas Lyte and that hung in the Great Parlour at Lytes Cary. This originally consisted of nine sheets of parchment joined together to form a square, approximately 2 metres along each side, though the four corner sheets are now lost. In an explanatory note, Lyte states that ‘for the better understanding of this generall worke’ he has divided it into ‘four severall tables’, the first tracing the descent of the British kings from Brutus, the second the descent of the Scottish kings from Gathelus, the third the ‘severall genealogies of the four conquering Nations’ (the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans) and the fourth the descent of the Pictish kings down to the defeat of Drusken by Kenneth, King of the Scots. These various lines of descent – including ‘The Danish Lyne’, ‘The Saxon Lyne’, ‘North Wales lyne’, ‘South Wales lyne’ and ‘Tuders Lyne’ – run in parallel along the foot of the manuscript (see fig 10) before finally converging on the central figure of King James.

According to Lyte, the Genealogy was compiled ‘out of the best and most approved Authors that have written either in French Latine or Englishe’. In fact the Genealogy relies heavily on a single source, Holinshed’s Chronicles, and to a lesser extent on the other standard chronicles (chiefly Harding and Stow) and, for the Welsh kings, on David Powell’s The Historie of Cambria, now called Wales (1584). Many of the supporting texts, such as John Leland’s Latin verses on King Arthur and Nicolas Roscarrock’s English translation of them, are taken straight from Holinshed, while the inscription on Henry vii’s monument in Westminster Abbey may have been copied from Camden’s Reges, Reginae, Nobiles (1600) or his Remaines (1605). Several of the illustrations also come from Holinshed: the image of the Stone of Scone, for example, which appears several times in the Genealogy, is a reversed copy of Holinshed’s woodcut of the marble stone of Gathelus (figs 4 and 5). Among other visual sources, the emblems of the English monarchs are copied from Jacobus Typotius’s Symbola Divina et Humana Pontificum, Imperatorum, Regum (1601); the oval portrait heads of Henry vii and Elizabeth of York (fig 6), and the figures of James i and Anne of Denmark, from a print by Renold Elstrack, The Most Happy Unions Contracted betwixt the Princes of the Blood Royall of theis towe Famous Kingdomes of England & Scotland (1603); while another Elstrack engraving, of James i in Parliament (1604) (fig 7), served as the source for the the Genealogy’s central image of James i (fig 8).Footnote 20

Fig 4 Image of the stone of Gathelus, from Raphael Holinshed, The Firste Volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande and Irelande (London, 1577), 4th section, A2r (p 3). Photograph: © The British Library Board

Fig 5 Image of the stone of Gathelus, copied from Holinshed, in the Lyte Genealogy (BL, Add ms 48343). Photograph: © The British Library Board

Fig 6 Portrait heads of Henry vii and Elizabeth of York, from the Lyte Genealogy (BL, Add ms 48343). Photograph: © The British Library Board

Fig 7 James I in Parliament (1604), engraved by Renold Elstrack (BM, 1856,0614.148). Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum; all rights reserved

Fig 8 James i, copied from Elstrack’s engraving, in the Lyte Genealogy (BL, Add ms 48343). Photograph: © The British Library Board

A reference in Lyte’s notebook to ‘Crinkyns Covenants for drawing and lymninge the kinges petegree’ shows that he commissioned a professional artist to illuminate the presentation copy of the Genealogy. J H P Pafford was the first to identify ‘Crinkyn’ as the London painter-stainer John Grinkin (fl 1586–1620), one of the leading artificers responsible for the Lord Mayor’s shows and other civic pageants in the early Stuart period.Footnote 21 Grinkin and Lyte may have been introduced by Anthony Munday, who was also involved in designing and producing the mayoral pageants, and, as noted above, inserted a fulsome compliment to Henry and Thomas Lyte in his 1611 Briefe Chronicle. Grinkin was certainly employed to illustrate the now-lost copy of the Genealogy that hung at Whitehall Palace; what is not so clear is whether he also drew the figures in the surviving uncoloured copy that probably served as the exemplar. Aubrey, who saw the manuscript on display at Lytes Cary in the 1670s, believed that Lyte was responsible for the text but not the drawings: ‘T. Lyte writt the best print hand that ever I yet sawe, the originall, which is now in the Parlour at Lytes-Cary, was writt by him with his hand, and limned by a famous Artist.’Footnote 22 However, Lyte’s godson, Thomas Baskerville, who also saw the Genealogy ‘set in a frame about 3 yards square … in the great parlor att Lytes Cary house’, believed that it was entirely Lyte’s own work: ‘beeing a curious pen-man, hee drew it on Vellam or parchment, illustrating [it] with the figures of Men women and other things agreeable to that history’.Footnote 23

We can learn more about the Lyte Genealogy by comparing it with two other pedigree rolls that were probably displayed alongside it in the parlour at Lytes Cary.Footnote 24 The first, written on four sheets of vellum (the upper sheet now missing), traces the Lyte family back to William le Lite (d. 1316) and his wife Agnes, whose kneeling figures, copied from a stained-glass window in the church of Charlton Mackrell, appear at the foot of the roll with the stem and branches of the family tree ascending from them in the conventional Jesse Tree format (fig 9). On either side of the family tree are a series of pen-and-ink copies of documents and funeral monuments, including the monument for Anthony Lyte (d. 1579) taken from a copper plate in Greenwich church ‘as I beheld the same and tooke a transcript of it in the yeer of our Lord 1610’, showing that the manuscript must post-date the Lyte Genealogy. The second roll, also on four sheets of vellum, and written in 1633, sets out the descendants of John Lyte (1498–1566) and his wife Edith (1521–56), their eight children and their respective families. The caption to John Lyte’s portrait emphasises his role in suppressing the Western Rising of 1549, noting that he joined with ‘other gentlemen of the Countrie in suppressing the Western Rebels who came soe farr as Kingweston neer Charlton and were there overthrowne by the power of the Countie’. This suggests that the manuscript was in part intended as a display of the Lyte family’s loyalty to the Crown and the county establishment, an especially sensitive subject for Thomas Lyte, who had been temporarily removed from the Somerset commission of the peace in the ‘great purge’ of 1625–6 when opponents of the Duke of Buckingham were put out of the county commissions.Footnote 25

Fig 9 Thomas Lyte’s portraits of William le Lite and his wife Agnes, c 1610 (SRO, DD/X/LY/1). Photograph: Somerset Record Office

The three rolls manifestly share a common origin. All are written in the same distinctive round hand that Aubrey described as Thomas Lyte’s ‘print hand’. All are drawn by the same artist, though the draughtsmanship of the two pedigree rolls is more fluent and assured than that of the earlier manuscript. All are highly idiosyncratic in design and execution. As Grinkin died in 1620, he cannot have had any hand in designing the second pedigree roll of 1633, and it therefore seems likely that all three manuscripts were written and drawn by Lyte himself, with the Genealogy conceivably being the item listed in Lyte’s inventory of papers as ‘The first draught of divers tables fixed in the kinges petegree’.Footnote 26 The drawings are certainly not beyond the capability of a talented amateur artist. The ‘print hand’ found in the three manuscripts bears little resemblance to the handwriting of Lyte’s few surviving letters, but his notebook shows that, like many practised writers in early modern England, he was able to vary his handwriting, alternating between a running secretary hand and a more formal bookhand. The variety of calligraphic hands used in the Genealogy and the facsimiles of medieval court hand in the earlier of the two pedigree rolls suggest that he also had access to a copybook such as Jean de Beauchesne’s A Book Containing Divers Sortes of Hands (1570).

These three genealogical rolls are among the most remarkable manifestations of early Stuart gentry antiquarianism. They reflect an obsessive concern with ancestral origins, an anxious awareness of social mobility and an almost mystical belief in the unifying power of consanguinity, expressed most clearly in the introductory caption to the 1633 pedigree roll in which Lyte explains his reasons for compiling the manuscript: ‘not for anye ostentation of birth or kinred … but only that those that are soe lately discended of one Parentage and from one Famelye might not be Strangers one to an other For as it has pleased God to advance some of them to honour and worshippe Soe some againe are humbled to a lowe & meane estate yet not to be despised for that they are discended of the same bloud and it may please God in a moment to raise them up againe.’ They also reveal Lyte’s strategic use of genealogy to create an appearance of continuity. The Lytes were hardly a united family: only a generation earlier, the family peace had been shattered by a bitter quarrel between Thomas’s father and grandfather, still traceable in the family records where Thomas noted ‘unkynd letters & worse dealinges betwixt Jo Lyte Esq & his son’.Footnote 27 The Lyte pedigree rolls were, among other things, a means of rendering these divisions invisible and presenting an image of seamless continuity across the generations. The Lyte Genealogy performed the same trick on a larger scale by smoothing over the ruptures in the line of British kings in order to present a seemingly unarguable case for the Stuart succession.

SUCCESSION AND UNION

The Lyte Genealogy is one of a number of royal pedigrees presented to James i soon after his accession. Other examples include George Owen Harry’s The Genealogy of the High and Mighty Monarch, James, by the Grace of God, King of Great Brittayne (1604), and Morgan Colman’s genealogical chart, Arbor Regalis, sive Genealogia Potentissimi Invictissimi et Augustissimi Monarchae Jacobi Primi (1604), which may have hung alongside the Lyte Genealogy in Whitehall Palace.Footnote 28 These were works of compliment and panegyric, produced in the hope of gaining royal favour, yet they also deal with two issues of the utmost political sensitivity, the Stuart succession and the Anglo-Scottish union. The Lyte Genealogy deserves attention not just as an exercise in panegyric but as a case-study in the application of antiquarian history to contemporary politics.

One of the most notable features of the Lyte Genealogy is its inclusion of the line of ancient British kings from Brute to Cadwallader, taken from Geoffrey of Monmouth (the ‘Galfridian myth’, as it is sometimes called). Several sixteenth-century historians, including Polydore Vergil in his Anglica Historia (1534) and George Buchanan in his Rerum Scoticarum Historia (1582), had already cast doubt on the veracity of the Brute legend, while Camden’s Britannia (1586) suggested that the name Britain derived not from the legendary Brute but from the Welsh word Brith, meaning painted or coloured, in reference to the ancient Britons’ custom of painting their bodies. Nevertheless, Camden ended by leaving the question open and inviting every reader to ‘judge as it pleaseth him’:

I beseech you, let no man commense action against me, a plaine meaning man, and an ingenuous student of the truth, as though I impeached that narration of Brutus; forasmuch as it hath been alwaies (I hope) lawfull for every man in such like matters, both to thinke what he will, and also to relate what others have thought. For mine owne part, let Brutus be taken for the father, and founder of the British nation; I will not be of a contrarie minde … Let Antiquitie heerein be pardoned, if by entermingling falsities and truthes, humane matters and divine together, it make the first beginnings of nations and cities more noble, sacred, and of greater maiestie: seeing that, as Plinie writeth, Even falsely to claime and challenge descents from famous personages, implieth in some sort a love of virtue.Footnote 29

Some modern commentators have argued that this passage is heavily ironic in tone. Others have suggested that it should be taken literally, as a pragmatic acceptance that myth and legend could still serve a useful purpose in supporting national identity. Contemporary readers, however, were in little doubt that Britannia represented a formidable challenge to the received theory of British origins. Henry Lyte complained that the critics of the Brute legend ‘have don no smale wronge to Britayn, espetially Camden whos Britannia beinge in the Latin tongue fleethe abroad in all the worlde as a Recorde against the true Originall of the moste noble Britaynes’. He even proposed that the book should be suppressed, and ‘master Camden or som other’ commissioned to write a revised edition, ‘with better advisement’, so that ‘the veritie of the Britishe historie’ could be reasserted.Footnote 30

This ‘Britishe historie’ took on extra significance with the accession of James vi of Scotland to the English and Welsh throne in 1603, as it made it possible to argue that the whole island had once been united under a single ruler. James’s union of the crowns could thus be seen not just as a unification but as a reunification. Such was the influence of Camden’s Britannia, however, that few of James’s advisers bothered to defend the Galfridian myth, despite its potential value as a precedent for the Anglo-Scottish union. Francis Bacon, in his Brief Discourse touching the Happy Union of the Kingdoms of England and Scotland, declared firmly: ‘It doth not appear by the records and monuments of any true history, nor scarcely by the fiction and pleasure of any fabulous narration or tradition of any antiquity, that ever this island of Great Britain was united under one king before this day.’Footnote 31 Sir Henry Savile, in his Historicall Collections on the Anglo-Scottish union, briskly dismissed the Brute legend as one of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ‘Welsh fables’, while, from the Scottish side, Sir Thomas Craig described it as immo nihil probabile (‘exceedingly improbable’) and argued that, at the time of the Roman invasion, Britain had been divided into several different states, each ruled by its own king.Footnote 32 There was thus fairly widespread agreement that, in Bacon’s words, James was ‘the first king that had the honour to be lapis angularis, to unite these two mighty and warlike nations of England and Scotland under one sovereignty and monarchy’.Footnote 33

Yet James himself was reluctant to give up the Brute legend. He had already used it in his treatise on government, Basilikon Doron (1599), as a warning to his son that ‘by deviding your kingdomes, yee shall leave the seed of division and discord among your posteritie; as befell to this Ile, by the division and assignement thereof, to the three sonnes of Brutus’. He drew on it again in a royal proclamation of 20 October 1604, which referred pointedly to ‘the blessed Union, or rather Reuniting’ of the two kingdoms.Footnote 34 Nor was the new school of sceptical Camdenian history necessarily opposed to the Galfridian myth.Footnote 35 Even some antiquaries in the Camdenian tradition, such as Sir Simonds D’Ewes, expressed a desire to hold onto the story of Brute in some form. In an unfinished treatise, ‘Brutus-Redivivus, or Brittaines True Bruto in parte discovered’, D’Ewes affirmed his belief in the ‘traditionall historie’ of Britain, which he complained was ‘too much derided by some that are learned’. In his view, there was every reason to believe that Brute had existed as a historical figure and given his name to Britain, even though the tale of his Trojan origin was clearly a later invention grafted onto the older tradition after the Roman conquest. ‘I make noe great doubt but that our true Brute was both setled here and this Island fullie knowen by that appellation it receaved from him: and (under Mr Camdens leave) before the Brittaines weere acquainted with that skill of painting or this land receav’d its appellation from soe poore a daubing.’Footnote 36

Thomas Lyte was not so unusual, therefore, in trying to salvage some elements of the traditional ‘British history’. Unlike his father, he was prepared to accept the force of Camden’s arguments, but in the Genealogy and its accompanying commentary, Britaines Monarchie, he offered a qualified defence of ‘the Brittish Genealogies and the Histories of Brute’ adapted from another of his source-texts, William Warner’s Albions England (1602). As for the truth of the Brute legend, he wrote,

I leave it disputable to the censure of our fore passed and modern Historiographers, my purpose being only to reduce that to order which Antiquitie hath left and we by tradition have received

And albeit I concurre with our learnedst Antiquaries that before the entrance of the Romans our Brittish History avoideth not the suspition of some fabulous errors, yet in soe generall a worke to have omitted a matter soe generally received had bene no otherwise than to delineat a bodie without a head or to have described a river without his proper fountaine.Footnote 37

Although Lyte could not bring himself to omit the legendary history altogether, he invited ‘those that are lesse affected to the History of Brute’ to ignore it and ‘descend lower to those cleerer streames issueing from our later Brittishe Kings and Princes of Wales from whome they may drawe a most perfect descent running by divers direct lynes to our gracious Soveraigne’.Footnote 38

The Lyte Genealogy is a product of what might be termed the ‘Galfridian moment’ shortly after James’s accession, when the Brute legend was pressed into service in support of the Anglo-Scottish union. Thomas Middleton’s verses for the triumphant procession welcoming James into London on 15 March 1604 are a good illustration of this strategic deployment of British history. As he entered the capital, James was greeted by the figure of Zeal, who invited him to take possession of his new dominions:

… so rich an Empire, whose faire brest

Containe four Kingdomes by your entrance blest,

By Brute divided, but by you alone,

All are again united, and made one.Footnote 39

In Anthony Munday’s pageant The Triumphes of Re-United Britannia, performed at the Lord Mayor’s show on 29 October 1605, Brute appears in the pageant to welcome James as ‘another Brute, that gives againe/To Britaine her first name’ and celebrate the peaceful reunification of the kingdoms:

And what fierce war by no meanes could effect,

To re-unite those sundred lands in one,

The hand of heaven did peacefully elect

By mildest grace, to seat on Britaines throne

This second Brute, then whom there else was none.

Wales, England, Scotland, severd first by me:

To knit againe in blessed unity.Footnote 40

John Ross’s Latin poem Britannica, published in 1607, illustrates the particular appeal of the Brute legend for common lawyers seeking to uphold the antiquity of British law.Footnote 41 But the most famous literary product of this Galfridian moment is Shakespeare’s King Lear, probably written around 1605–6 and typical of the early Jacobean period in its concern with the dangers of dividing a united kingdom.

A further notable feature of the Genealogy is that it traces the succession back to Brute via multiple lines of descent. The basic case for the Stuart succession rested on James’s descent from Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry vii and Elizabeth of York. James himself, in his speech to Parliament on 19 March 1604, declared that ‘by my descent lineally out of the loynes of Henry the seventh, is reunited and confirmed in mee the Union of the two Princely Roses of the two Houses of Lancaster and Yorke’.Footnote 42 This had the advantage of emphasising the blood-relationship between James and Elizabeth i and aligning the case for James’s hereditary right with the existing arguments for the Tudor succession. However, it was also open to several objections: first, that Henry viii’s will had conspicuously passed over the Stuart claim; secondly, that James, as a Scot, was barred from the English throne by the common-law rule against alien inheritance.Footnote 43 Both these objections were raised by Robert Parsons in his succession tract, A Conference about the Next Succession to the Crowne of Ingland (1594), in which he presented James as merely one of a host of possible candidates and argued that the strongest claimant was the Spanish Infanta. Parsons’s aim may not have been so much to promote the Infanta’s claim as to spread doubt and confusion over James’s claim. If so, he certainly succeeded. Susan Doran has argued that, until 1595, ‘James had every reason to feel confident that his title to the English throne was reasonably secure’. The publication of Parsons’s Conference altered his attitude and made him considerably more anxious about the possibility of a disputed succession.Footnote 44

The response of James’s apologists was to come up with increasingly elaborate arguments in defence of the Stuart succession. As Parsons had argued that the Infanta’s hereditary claim could be traced back to William the Conqueror, his opponents sought to go one better by tracing James’s claim back to the pre-Conquest period. Sir Robert Cotton, in a tract presented to James shortly after his accession, argued that the Stuart line could be traced back to Edgar, King of the West Saxons, who called himself King of all Britain, ‘as many of his charters at this day warrant’. James thus united the Norman and Saxon lines, and as well as being ‘the just and lawful successor to all the Norman race, may undoubtedly deduce from Edgar in blood (which the Conqueror properly could not) the stile of King of Brittain’.Footnote 45 Sir Thomas Craig put forward an even more elaborate argument from hereditary succession in which he maintained that the Romans, the Saxons and the Danes, ‘the three royal houses which at different times have claimed the crown of England’, were all united in the person of James. The Roman claim had passed by natural law to the Picts and Scots when the Romans abandoned Britain, and therefore belonged to the Scottish kings; while the Saxon claim had passed from Edward the Confessor to his niece Margaret, and thence to Margaret’s husband, Malcolm Canmore, King of the Scots. Craig did not discuss the Danish claim in any detail, but it could be argued that this too had passed to James through his marriage with Anne of Denmark.Footnote 46

These arguments varied according to national preferences. Cotton’s was an Anglocentric argument, hinging on the assertion that the Saxon King Edgar had been ‘victorious over the Kings of Scotland, Orcades and the Isles’ and had therefore earned the right to call himself King of all Britain. Craig’s was a Scotocentric argument, which held that the right to the English throne had descended through the Scottish kings, even though the rightful heirs had been excluded for more than 500 years by the Norman Conquest. Morgan Colman’s Arbor Regalis puts Craig’s argument into visual form by giving a central place to the marriage of Margaret and Malcolm Canmore, the Anglo-Scottish union in posse which James’s accession to the English throne would later accomplish in esse.Footnote 47 What these arguments have in common, however, is the idea of multiple lines of succession converging providentially on James. This is the key to the Lyte Genealogy too, with its branching lines of descent ingeniously combined in one diagram like the Tube lines on the map of the London Underground (fig 10). Lyte was not merely a Somerset backwoodsman obsessed with the romantic myth of Britain’s Trojan past; he was fully up to date with the arguments used to justify the Stuart succession, and the Lyte Genealogy is a formidable and sophisticated piece of propaganda designed to put James’s right to the throne beyond all reasonable doubt.

Fig 10 Parallel lines of royal descent, from the Lyte Genealogy (BL, Add ms 48343). Photograph: © The British Library Board

The Genealogy thus contains several different layers: a celebration of James as a second Brute, dating from around 1604–5, overlaid by a more complex defence of the Stuart succession, which may have evolved and developed over a longer period of time. By 1610, when Lyte presented the manuscript to the King, the project for a full Anglo-Scottish union was no longer politically feasible, but the Genealogy still had its uses in upholding James’s title to the throne and, not least, in presenting the principle of hereditary succession as the natural order of things.Footnote 48 Hung in its ‘place of eminence’ at Whitehall, the Genealogy would have been a highly prominent, vividly coloured and fascinatingly intricate expression of the antiquity and legitimacy of the Stuart monarchy. The engraved copy of the Genealogy could have been even more valuable for propaganda purposes: among the diplomatic gifts brought to Japan by the English ship Advice in 1616 was ‘1 genelogy all kyngs from Brute’ – almost certainly a copy of the now-lost engraving.Footnote 49 This helps to explain the balance of exchange between the Lyte Genealogy and the Lyte Jewel, and it is to the Jewel that we now turn.

THE LYTE JEWEL

The Lyte Jewel has been justly described as ‘the finest Jacobean jewel in existence’.Footnote 50 It was presented to Lyte by James i in 1610 or 1611. The exact date of presentation is unknown, but it must have been between 12 July 1610, when Lyte presented the Genealogy, and 14 April 1611, when Lyte had his portrait painted wearing the jewel. It may well have been a New Year gift, as Lyte’s inventory of his papers and possessions includes a reference to ‘Newyeers giftes brought me in Anno 1611’.Footnote 51 Whatever the circumstances of the gift, it belongs to a culture of gift-giving and gift-exchange at the early Stuart court that had rarely been seen in England on such a lavish scale.Footnote 52

The will of Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset, shows how James used jewels to cement fealty and allegiance at court. It mentions a ring ‘sett with twentie diamonds’ given him by James, which was to descend ‘from heire male to heire male of the Sacuilles after the Decease of euery one of them, seuerally and successiuelie’.Footnote 53 Sackville’s will shows that he owned other fine diamonds, and his accounts for the last year of his life list jewels sold or altered by the royal jeweller Abraham Hardret.Footnote 54 The ring given to him by James, however, had exceptional significance, as it had been delivered to him during his recent illness with:

this Royall message vnto me namelie that his highness wished a speedie and a perfect recouerye of my healthe with all happie and good Success vnto me, and that I might live as long as the Dyamonds of that Rynge (which wherewithal he Deliuered vnto me) did indure. And in token thereof required me to weare it and keepe it for his sake. This most gracious and comfortable message restored a newe life vnto me as coming from so renowned and benigne a Soueraigne vnto a Seruante so farre vnworthie of so greate a favoure.Footnote 55

Portrait jewels, carrying the king’s likeness, had a special role to play in the culture of gift-giving at court. To mark the signing of the Treaty of London in 1604, concluding decades of war between England and Spain, James had a special portrait medal struck in gold.Footnote 56 The example in the British Museum is probably one of the ‘certain medallions to the number of twelve in gold’ for which Nicholas Hilliard was paid by the king in December 1604 (fig 11).Footnote 57 The portrait on the obverse closely resembles Hilliard’s first portrait type of James in his painted miniatures.Footnote 58 The integral suspension loop shows that the medal was designed to be worn on a chain or ribbon around the neck, as a token of loyalty and honour.Footnote 59 The model for the Peace with Spain medal, as for James’s coronation medal – the first for an English ruler – was almost certainly continental, another indication of the way in which James i was aligning himself as a peacemaker and major actor on the European stage.Footnote 60

Fig 11 Gold medal of James vi and i designed by Nicholas Hilliard, commemorating Peace with Spain, 1604. Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum; all rights reserved

The reign of James i also saw the rise of the tablet – a portrait miniature incorporated into a jewel – which had first become fashionable in the last two decades of Elizabeth’s reign.Footnote 61 Anne of Denmark was often depicted wearing a tablet jewel, and gave them to others as tokens of love, affection and diplomatic friendship.Footnote 62 Her jewellery inventory of 1606 lists two tablets with miniatures of her much-loved brother, Christian iv of Denmark.Footnote 63 Tablets made for Anne by the jeweller George Heriot took a number of forms, often adapted from flowers and plants, such as ‘a tablet for a picture in frome of a baye leafe set with threescore and eleven diamonds’ supplied by Heriot in April 1609, which incorporated ‘a large diamond cutt with facets and a large triangle diamond’, costing £42, and nine smaller diamonds, costing £27. Another ‘jewell for a picture set with 160 diamonds in forme of an pensee [pansy]’ was supplied in March 1610, while in June 1611 Heriot billed the Queen for ‘making a Casse for a picture on the back syde of a rose of diamonds’ with a ‘Cristall’ to protect the miniature.Footnote 64 The papers of Sir William Herrick, another of the King’s jewellers, contain further references to tablet jewels, such as ‘one tablet of Graven worke inamiled beinge sett with divers smale diamondes & one pearle pendant with the Kings Maiesties pikture in it and a Christall ouer the same’ belonging to Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, and valued at £50 in 1609.Footnote 65

The centrepiece of the Lyte Jewel is a fine miniature of James i unsigned but attributable to Nicholas Hilliard.Footnote 66 James granted Hilliard a monopoly for the production of royal portraits in 1617, calling him ‘our wel-beloved Servant Nicholas Hilliard, Gentleman, our principal Drawer for the small Purtraits and Imbosser of our Medallions of gold’. The privilege was given on account of his ‘extraordinary Art and Skill in Drawing Graving and Imprinting of Pictures, of us and others’.Footnote 67 James might not have agreed with Hilliard’s bold claim that limning was ‘a thing apart’ which ‘excelleth all other painting whatsoever … being fittest for the decking of princes’ books, or to put in jewels of gold’, but he was keenly aware of the power of the portrait in different formats as a propaganda tool.Footnote 68 Supplying James with miniatures required the assistance of Hilliard’s former apprentices, as shown in the only other miniature of James to have survived in its contemporary tablet setting. Known as the Ark Jewel, it is much smaller, with a simple enamelled gold case. The portrait of James i is of Hilliard’s second type (c 1609–14), as used in the Lyte Jewel. Unlike the Lyte Jewel, however, it is a studio production, not from Hilliard’s own hand.Footnote 69 As late as 18 October 1615, Hilliard was still supplying miniatures of the king in gold and jewelled cases: he was paid £35 ‘for work done by him aboute a table of his Ma[iestie]s picture garnished with diamonds given by his Ma[ies]tie to John Barkelay’. He also profited from leasing out his designs to other artists, as in Michaelmas 1618, when he was paid for a ‘small picture of his Ma[ies]tie delivered to Mr Herryott his Ma[iestie]s jeweller’.Footnote 70

THE MAKER OF THE JEWEL

George Heriot, the king’s jeweller, was born in 1563 and admitted as a freeman of the Incorporation of Goldsmiths of Edinburgh on 28 May 1588, having served his apprenticeship with his father. Like many Edinburgh goldsmiths, he came from a family steeped in the craft: his father, George Heriot the Elder, was a prominent goldsmith and city figure in his own right, whose working career overlapped with that of his son until his death in 1610. George junior, however, achieved far greater fame than his father.Footnote 71 He developed as a fine craftsman to such an extent that on 17 July 1597 he was appointed as goldsmith to Queen Anne, and, on 4 April 1601, as jeweller to James vi.Footnote 72 He was one of several Scottish craftsmen who followed James to London in 1603, establishing his business in the parish of St Martin in the Fields. His accounts show that supplying the Stuart dynasty with jewels and regalia was an extremely lucrative business, but he was very much more than a master-craftsman, acting also as what has been called a ‘credit-creator’, lending money on security to service the king’s debts.Footnote 73 By the time of his death in 1624 he had amassed a fortune of some £50,000 sterling, much of which went to establish Heriot’s Hospital (now George Heriot’s School) in his native city of Edinburgh.

Heriot has long been considered a strong candidate for the making of the Lyte Jewel,Footnote 74 and that link has been made stronger now that the Eglinton Jewel (fig 12), in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, has been clearly identified as a piece documented as having been commissioned and supplied by Heriot in 1610.Footnote 75 The Eglinton Jewel is not only the first surviving jewel to have been traced to Heriot, it is also the earliest extant tablet with a royal cipher or jewelled letters of a kind that appears to have been highly fashionable at the early Jacobean court. The case has a translucent red enamelled cover with collet-mounted table-cut diamonds set in the form of two ‘S’s , two linked ‘C’s and Anne’s own personal cipher ‘CAR’ with a crown above (the initial C is undoubtedly a reference to her beloved brother, Christian iv of Denmark). This jewel is one of the best documented pieces of early seventeenth-century jewellery in existence. As Diana Scarisbrick has argued, it is surely the item described in George Heriot’s account to the Queen in 1610 as ‘a tablet with a cipher A and C set on the one side with diamonds’.Footnote 76 It is also faithfully depicted in the portrait of Lady Anne Livingstone, Countess of Eglinton, by an unknown artist, painted in 1612 to mark her wedding to Sir Alexander Seton of Foulstruther, later 6th Earl of Eglinton.Footnote 77 Indeed, the jewel may have been given as a wedding present to Lady Anne by the Queen after whom she was named. It is shown attached by a ribbon-bow knot over her heart as a mark of regard from the Queen, with a pendant pear-shaped pearl below, possibly the same one that the Queen gave her in 1607.Footnote 78

Fig 12 The Eglinton Jewel, enamelled gold with miniature of Anne of Denmark by the studio of Nicholas Hilliard, c 1610. The case has Anne of Denmark’s crowned cipher, ‘CAR’, two ‘S’s and intertwined ‘C’s worked in diamonds and set on enamelled gold. Photograph: © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The final, conclusive and indeed most unusual piece of evidence comes from another Heriot document. On the reverse of an itemised account of jewels supplied to the Queen from 9 March to 20 September 1606 is a series of pencil sketches outlining an empty oval, an oval enclosing a cipher ‘CAR’, a cipher ‘ASR’ not in an oval, and then a more fully worked-up cipher surmounted by a crown and set with table-cut stones within an oval (fig 13).Footnote 79 The sheet also contains some entirely unconnected rough arithmetical jottings. The conclusion is that this is a ‘back of the envelope’ working diagram, created on a piece of scrap paper snatched up from the goldsmith’s table to make a sketch of how such a piece could be developed, possibly in response to being given a verbal request for the jewel. In its final realised form, the Eglinton Jewel is not an exact match of the most developed of the sketches; the crowned cipher is different, the positioning of the collet-mounted diamonds is different and the ‘C’s and ‘S’s do not appear on the sketches. There is little doubt, however, that the drawings are the initial designs for this piece and, as such, are a delightfully unexpected and personal link with the creator of this fascinating jewel.Footnote 80

Fig 13 George Heriot, design for the Eglinton Jewel sketched on an itemised account of jewels supplied to Anne of Denmark between 9 March and 20 September 1606 (National Archives of Scotland). Photograph: image reproduced by kind permission of the Governors of George Heriot’s Trust

The diamond cipher on the front of the Eglinton Jewel is one obvious link with the Lyte Jewel.Footnote 81 However, one of the outstanding features of the Lyte Jewel is its strongly architectonic design, in which every detail has been carefully planned and executed. The front cover is an openwork grille pierced to form the royal monogram IR (Jacobus Rex). The monogram is formed from two narrow bands of white enamel set with eight table-cut diamonds; even though these differ from one another in size, they have been skilfully matched and set in their gold collets. The gold is cut away on either side of each diamond so as to accentuate the royal monogram. Like the contemporary album of record designs of jewellery associated with Arnold Lulls, the Lyte Jewel documents the early Jacobean fashion for jewellery intended to show off carefully selected and well-cut gemstones while minimising their setting.Footnote 82 Openwork settings on miniatures allowed the underlying portrait to glow through when seen in daylight. The Lyte Jewel’s construction allows the rich red hanging behind the bust of James i to be seen to striking effect behind the royal cipher. A similar effect is seen in Hilliard’s miniature of Elizabeth i as the Star of Britain, dating to around 1600, which is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.Footnote 83 Another tablet in the Fitzwilliam Museum, dating to around 1600–10 but now containing a later miniature, has a closely comparable openwork frame with a ‘Heneage knot’ picked out in rubies set in gold.Footnote 84

Apart from the pierced cover, another notable feature of the Lyte Jewel is its openwork border, which emphasises the quality of the diamonds selected to decorate it. The border is made up of two parallel bands of white enamel, pierced so as to set off the sixteen table-cut diamonds by alternating them with sixteen openwork rectangles. This gives the outer band of diamonds exceptional prominence when the jewel is worn, as shown in the Lyte portrait. The Heneage Jewel is an earlier and simpler version of this kind of setting, forming spokes around the Queen’s profile, dating to around 1595.Footnote 85 The Lesser George of Christian iv’s younger brother, Duke Ulrik, which was probably made in London around 1605, shows a development of this openwork diamond edging that is close to the Lyte Jewel in conception (fig 14). Duke Ulrik travelled to England to visit his sister, Anne of Denmark, and her husband, James i, and stayed in London from November 1604 to June 1605. During his stay he received the Order of the Garter, with a Lesser George set with an agate cameo of St George and the Dragon. He was twice portrayed wearing it. Duke Ulrik’s Lesser George stands between the Heneage Jewel and the Lyte Jewel in the design of its border.Footnote 86

Fig 14 The Lesser George of Ulrik John of Denmark, Duke of Holstein and Schleswig, sardonyx and enamelled gold, London, c 1605. Photograph: Rosenborg Castle (The Danish Royal Collections)

Diamond initials are also prominently used on the case of a tablet in William Larkin’s portrait of Elizabeth Drury, Lady Burghley, which has been dated to around 1615 (fig 15). Like the Countess of Eglinton, Lady Burghley wears her tablet on her left breast, but the jewel is attached by a gold dagger in this case, rather than a ribbon.Footnote 87 It is worn to striking effect against deep black, contrasted with a pearl headdress or tire in the hair, thick ropes of pearls around the shoulders secured by a diamond brooch, pearl-studded buttons on the bodice and sleeves, and an elaborate lace collar. The jewel has a frame of table-cut diamonds with a pendant pearl, and the interlaced initials ‘RD’ worked in table-cut diamonds, as on the Lyte Jewel, at its centre. The monogram is that of her brother, Robert Drury, who died on 2 April 1615; it has been suggested that the Countess wore this tablet, perhaps containing a portrait of her brother, in his memory.Footnote 88

Fig 15 William Larkin, portrait of Elizabeth Drury, Lady Burghley, oil on canvas, c 1615. Photograph: reproduced by kind permission of Derek Johns, London

The survival of tablets was secured by their role in the history of a family. It is significant that three famous surviving examples – the Drake, the Eglinton and the Lyte Jewels – are all shown being worn in portraits of their original owners. This may have been vital in reinforcing the link between a jewel and a famous ancestor through the generations, ensuring a jewel’s survival. The Drake Jewel of c 1580–90 is said by tradition to have been given to Sir Francis Drake by Elizabeth i, and it appears in two versions of the same portrait of Drake by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. The one in the National Maritime Museum is dated 1591 (fig 16), which provides a terminus ante quem for the Jewel, which cannot otherwise be closely dated.Footnote 89 Perhaps the presentation of the Jewel had prompted the commissioning of the original portrait on which these two surviving examples are thought to have been based. This is suggested by the way in which the cameo Jewel, set with fine table-cut rubies and diamonds, has been delineated with care and given great prominence, along with his arms, a globe and a rapier, symbolising Drake’s attributes as an adventurer, circumnavigator and courtier.Footnote 90

Fig 16 Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Francis Drake (showing the Drake Jewel), oil on canvas, dated 1591. Photograph: © Royal Museums Greenwich

In the case of the Lyte Jewel, as with the Eglinton portrait, it would appear that the gift of the Jewel prompted Lyte to have his portrait done proudly wearing it as a token of royal favour (fig 17). The oil portrait on panel presents Lyte wearing sober and expensive black, with a starched linen collar over a supportasse.Footnote 91 The plainness of his costume suggests a wish to present himself as a country gentleman rather than a courtier. He is flanked by his arms at the top left, and a Latin inscription at top right recording the sitter’s age as forty-three, and dating the portrait to 14 April 1611. The Jewel is worn on a broad red ribbon around his neck. It has been precisely delineated: the monogram is clearly shown, and each diamond is in its correct place so as to identify the Jewel. The only original element of the Lyte Jewel not to have survived is also shown in this portrait: a trilobed diamond pendant, which was missing by 1882.Footnote 92 Tablets generally had pendants made from a single pear-shaped pearl; diamond pendants seem to have been a luxury: a ‘pendant sett with two rose diamonds which was hunge at a tablett XIIs [12 shillings]’ was important enough to be listed as a single item in Heriot’s accounts for May 1611.Footnote 93

Fig 17 Anonymous artist, Thomas Lyte, oil on panel, dated 14 April 1611. Photograph: Museum of Somerset, Taunton; © Somerset County Council Heritage Service

Given its quality and sophistication, the Lyte Jewel has always been seen as a bespoke jewel, specially commissioned for presentation to Lyte. Heriot’s accounts with Queen Anne may, however, suggest an alternative origin, for they show that between 1607 and 1617 no fewer than twenty tablets with miniatures were made or repaired in Heriot’s workshop. Their price varied greatly according to the quality of the diamonds and the complexity of the setting. One tablet ‘sett with Diamonds on the one side’, which was to be sent ‘to her ma[iesties] mother the Queene of Denmark’, cost £66 in 1607. This was at the low end of the price range; towards the top was ‘a tablet of gold made for two pictures and sett on both sides with diamonds’, costing £250 in July 1609.Footnote 94 The most expensive was ‘a great tablet for a picture sett with 200 diamonds great and small’, valued at £350 in April 1609.Footnote 95 As we cannot deduce the value of the twenty-nine diamonds incorporated on one side of the Lyte Jewel, we cannot estimate its exact status in relation to the Heriot tablets in the documents. Given the quantity of tablets, and the number of diamonds, passing through Heriot’s hands at the time when the Lyte Jewel was made – and he was not the only jeweller supplying James i at the time – it is possible that the Jewel could have been made for another recipient and then recycled as a gift for Lyte. This would fit the picture we have of the way in which Anne of Denmark’s jewels were in constant circulation, being taken from her and given as presents, broken up and remodelled for other uses at court.

Whether the Lyte Jewel was bespoke or not, the diamonds used to make it may well have been taken from other jewels and then carefully selected as a group. Even so some of the facets appear to have been broken or chipped before they were set into their gold collets. The gem-setter has improved the forms by extending the facets of the gold setting smoothly into the edges of the collets to make the gems look larger and more evenly shaped and sized. These deep closed-back settings allow the setter to incorporate foils behind the gemstones to enhance the brilliance of the diamonds. Cellini’s Goldsmiths’ Treatise gives the recipe for a black resin to set behind diamonds in closed-back settings.Footnote 96 Close examination of the Lyte Jewel under strong magnification indicates that seventeen of the twenty-nine diamonds have been enhanced by this method.Footnote 97 Contemporary painters recognised the jeweller’s practice – and contemporary taste in how best to show off diamonds – by portraying diamonds as black gems with white highlights.Footnote 98 The anonymous portrait of Thomas Lyte wearing the Jewel shows this particularly well.

The enamelling on the Lyte Jewel (fig 18) has more to tell us of the Jewel’s origins and its continental European aspects. The inside of the lid of the Lyte Jewel is enamelled in translucent red, green, blue and white on the back of the diamond settings, while the back of the outer frame is stippled.Footnote 99 The enamelling is of the very highest quality and in the latest design, executed in fine gold curves and C-scrolls in a white ground; the junctions have been strengthened with halberd-like blocks in red enamel. The decoration resembles that on the inside of a miniature case in Vienna, which is documented in the 1619 inventory of the Emperor Mathias as having originally contained ‘a portrait or miniature of the king of England’. The reference is probably to James i, dating the tablet to the period 1603–19.Footnote 100 It represents a type of grotesque strapwork known in German as schweifwerk (‘tailwork’). This light and delicate precursor to the fully developed ‘peascod’ styleFootnote 101 – perfectly adapted to the needs of enamellers making champlevé-enamelled jewels – was rapidly disseminated throughout northern Europe during the 1590s.Footnote 102

Fig 18 Detail of enamelling on the back of the Lyte Jewel, London 1610–11. Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum; all rights reserved

Surviving sets of dated engraved designs of this type are rare, but it is evident that whoever enamelled the Lyte Jewel in London was keenly aware of the latest continental fashions. There is an affinity with the designs for engraved ornament by Corvinianus Saur, court goldsmith to Anne of Denmark’s brother, Christian iv of Denmark, which were published between 1591 and 1597.Footnote 103 Similar too are the designs for enamelling in blackwork of Guillaume de la Quewellerie, a Protestant goldsmith from Oudenaarde, which were published in Amsterdam by Willem Janszoon Blaeu in 1611.Footnote 104 The work of the Protestant goldsmith Jacques Hurtu is also close to the enamelling style on the Lyte Jewel. Hurtu was the son of the Protestant goldsmith from Orléans who followed his brother Guy to London and is documented as working in Blackfriars in 1585.Footnote 105 In 1594 he was sworn to the Ordinances of the Goldsmiths Company in London. We do not know when he left London, though he published a set of engraved designs in Paris in 1614, showing his knowledge of the very latest fashions and his contribution to the development of the peascod style.Footnote 106

This broadly northern European style of ornament and the migration of jewellers between different European goldsmiths’ centres make it difficult to pin down the Lyte Jewel as anything other than a London product, very likely the work of a number of talented stranger jewellers – immigrant craftsmen. It is probably the best documented example of a process whereby a jewel could be ‘fashioned in London of a stone supplied by a German merchant, cut by a diamond cutter from Antwerp, set and enamelled by a jeweller from Paris, designed from a print by a goldsmith from Geneva, with the whole process controlled and directed by a royal jeweller from Scotland’.Footnote 107

CONCLUSION

The house and estate at Lytes Cary remained the property of the Lyte family until the mid-eighteenth century, when Thomas Lyte (1694–1761), great-great-grandson of the antiquary, fell on hard times. In 1740 he conveyed the house to trustees in order to protect it from his creditors, and in 1748 he surrendered his life interest to his son John.Footnote 108 In 1755 the property was finally sold. By that time, however, the family heirlooms had already passed to Thomas’s uncle, Thomas Lyte of New Inn (1673–1748), a wealthy London attorney, who acquired the portrait, the jewel and the remaining family papers. The importance he attached to them is shown by their prominence in his will, where the portrait and the jewel are the first movables to be bequeathed, before plate and other furnishings:

I also give unto my said daughter, Silvestra Blackwell, during her life, the possession and use of my great grandfather’s picture, and of the jewell which is set round with diamonds, and hath also some other diamonds on the top thereof, and in the inside hath the picture of King James the First (the same being given by him to my said great grandfather) and of which jewell there is also a picture under my said great grandfather’s picture.Footnote 109

Both objects passed by family descent to Laura Dunn Monypenny (1832–94), who sold the Lyte Jewel after the death of her father in 1854. It was acquired by the 11th Duke of Hamilton (1811–63), a keen collector of Stuart relics, who lent it to the South Kensington Exhibition along with other Stuart miniatures in 1862.Footnote 110 At the sale of the Hamilton Palace collection in 1882 it was bought for £2,835 by the dealer E Joseph for Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild.Footnote 111 The Jewel had a prime position in the New Smoking Room at Waddesdon Manor. On Baron Ferdinand’s death in 1898, it was bequeathed to the British Museum as part of the cabinet collection known as the Waddesdon Bequest.Footnote 112 The portrait was bequeathed by Miss Monypenny to Sir Henry Maxwell Lyte, and remained in family hands until it was sold at Sotheby’s, London, on 3 February 1960 (lot 70) and acquired by Somerset County Museum through the National Portrait Gallery.Footnote 113

The Genealogy had a more chequered history. Its damaged condition, with the four corner panels missing, suggests that it might have remained at Lytes Cary after the sale of the house and been salvaged at a later date. Sir Henry Maxwell Lyte was unaware of its existence when he published his detailed history of The Lytes of Lytescary in 1892, but at some point before 1918 it was sold by the firm of Bernard Quaritch to the collector Howard Coppuck Levis (1861–1935), who illustrated it in a privately printed monograph on Bladud, the legendary founder of Bath.Footnote 114 Levis sold it to Sir Henry Maxwell Lyte at the price he had paid for it – £152 – and it remained in the family until 1954, when Walter Maxwell Lyte, on behalf of his son J W Maxwell Lyte, offered it to the British Museum for £325 on account of its integral connection with the Lyte Jewel. The initial response was unenthusiastic. It was rejected by the Department of Prints and Drawings and passed on to the Department of Manuscripts, where C E Wright reported that it was ‘remarkable only as an antiquarian curiosity, the illustrative material being derived from the stock-in-trade of the engraver of the period’. A J Collins, the Keeper of Manuscripts, recommended that the offer be declined, but he was overruled by the Trustees, probably at the prompting of Sir Thomas Kendrick, the Director, who had written about Henry Lyte in his book British Antiquity only a few years earlier.Footnote 115 Following its exhibition at the British Museum in 2012, the Genealogy underwent treatment in the British Library’s Centre for Conservation, and its five panels have now been separated and individually mounted.Footnote 116

The time has now passed when the Genealogy could be dismissed merely as an antiquarian curiosity. Together with the Jewel, it is a product of the intellectual ferment and creative flowering that resulted from the Stuart succession and the conceptual shift from the history of England to the history of Britain. Shakespeare’s Jacobean plays – particularly his two Ancient British plays, King Lear and Cymbeline, and his Scottish play, Macbeth – belong to the same cultural moment. Lear, as already noted, is typically Jacobean in its preoccupation with the dangers of a divided kingdom; Cymbeline ends with the reunification of Romans and Britons and the convergence of their claims to political legitimacy; while Macbeth famously traces the line of succession through a show of eight kings summoned up for Macbeth by the three witches.Footnote 117 Ever since the time of Malone, Shakespearean scholars have recognised that these three plays hang together both chronologically and thematically. Shakespeare and Lyte both drew their history from a common source – Holinshed’s Chronicles – and there is no reason to suppose that they were influenced by each other. But if Shakespeare visited Whitehall with the King’s Men after 1610, he would have seen the Lyte Genealogy on display, with the names of Lear and his three daughters (fig 19), as well as those of Banquo and Fleance in the now-lost panel showing the succession of the Scottish kings. It would have been a reminder that the legendary history of Britain still had potent political resonance.

Fig 19 Detail from the Lyte Genealogy, showing King Lear and his three daughters, ‘Ragan’, ‘Gonorilla’ and ‘Cordeilla’ (BL, Add ms 48343). Photograph: © The British Library Board

The Lyte Jewel too has its Shakespearean echoes. Shakespeare was aware of the fashion for jewelled miniatures in tablet form: when Olivia gives a jewel to Viola in Twelfth Night, the gift is clearly glossed as a tablet: ‘wear this jewel for me, tis my picture’. In Shakespeare and Middleton’s Timon of Athens (c 1604–6), the giving and wearing of jewels creates bonds of honour and allegiance. Timon, like James, is continually spending and giving to maintain his popularity and position. At dinner he summons a servant to bring him a casket, and presents a jewel to one of his companions: ‘look you, my good lord, / I must entreat you honour me so much / As to advance this jewel – / Accept it and wear it, kind my lord.’ The recipient responds gracefully, ‘I am so far already in your gifts’, to the general murmur, ‘So are we all’, while Timon’s servant, aside, frets about his master’s extravagant generosity: ‘More jewels yet? / There is no crossing him in’s humour.’ It is possible, as some scholars have suggested, that Shakespeare and Middleton intended their audience to draw a direct parallel between Timon’s profligacy and James’s lavish expenditure.Footnote 118 What is certain is that they were well aware of the importance of jewellery, and its display, in the gift economy of the Jacobean court.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Edward Town for our initial discussions on the Lyte Genealogy and its making, and for help with the archival research in the National Archives. We are also grateful to Natasha Awais-Dean for allowing us to cite her PhD thesis, which is soon to be published by the British Museum.