Introduction

Temperature largely determines the manner in which glaciers move, erode, and deposit sediment (Hambrey Reference Hambrey1994). Glaciers are identified as polar, temperate, or polythermal (Hooke Reference Hooke1998). The base of temperate glaciers is at the pressure-melting point of ice and, therefore, these glaciers are wet-based. Temperate glaciers are effective in eroding their substrates and transporting large masses of sediment. In contrast, the colder polar glaciers are dry-based. They achieve little erosion and transport smaller masses of sediment. Polythermal glaciers have variable temperatures and are wet-based in some parts and dry-based in others.

Wet-based glaciers played a key role in sculpting the Transantarctic Mountains prior to and during the Miocene (Stroeven & Kleman Reference Stroeven and Kleman1999, Atkins et al. Reference Atkins, Barrett and Hicock2002, Denton & Sugden Reference Denton and Sugden2005, Atkins & Dickinson Reference Atkins and Dickinson2007). Dry-based glaciers are common today in the Transantarctic Mountains (Lorrain et al. Reference Lorrain, Fitzsimons, Vandergoes and Stievenard1999, Cuffey et al. Reference Cuffey, Conway, Gades, Hallet, Lorrain, Severinghaus, Steig, Vaughn and White2000, Davies & Fitzsimons Reference Davies and Fitzsimons2004, Atkins & Dickinson Reference Atkins and Dickinson2007, Marchant & Head Reference Marchant and Head2007). Landforms associated with dry-based glaciers in Antarctica include boulder-belt (drop) moraines, sublimation tills, and rock glaciers (Marchant & Head Reference Marchant and Head2007).

Former dry-based glaciers have been reported on Svalbard (Wadham et al. Reference Wadham, Hodson, Tranter and Dowdeswell1997), northern Scandinavia (Kleman Reference Kleman1994, Stroeven & Kleman Reference Stroeven and Kleman1999), and other regions. Landforms such as eskers, drainage channels, and boulder fields have escaped destruction in Antarctica (Näslund Reference Näslund1997) as well as in Fennoscandia (Kleman Reference Kleman1994) despite complete overriding of ice.

During investigations of the glacial history of the Transantarctic Mountains, several unique features of landforms modified by glaciers were observed that provide clues as to glacial mechanisms. The objective of this study is to relate the mode of glaciation, i.e. dry-based vs wet-based, to the occurrence of buried soils and the recycling of clasts.

Methods

The study has focussed on the glacial history of the Transantarctic Mountains from north Victoria Land through southern Victoria Land (Bockheim et al. Reference Bockheim, Wilson, Denton, Andersen and Stuiver1989, Denton et al. Reference Denton, Bockheim, Wilson, Leide and Andersen1989) (Fig. 1), with an emphasis on the McMurdo Dry Valleys (Fig. 2), utilizing a glacial reconstruction scheme that considers the interaction of outlet glaciers from the East Antarctic ice sheet, alpine glaciers along valley walls, and advances of grounded ice in the Ross embayment into the mouths of valleys. In addition to radiometric dating, it relies heavily on soils as stratigraphic markers and for relative dating (Bockheim et al. Reference Bockheim, Wilson, Denton, Andersen and Stuiver1989).

Fig. 1 Location of the study areas in the Transantarctic Mountains.

Fig. 2 Location of sampling site place names in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Satellite image courtesy of National Aeronautics & Space Administration.

So far nearly 1000 pedons have been described and sampled in the Transantarctic Mountains. Data from 482 sites are available in the University of Wisconsin Antarctic Soils Database (http://nsidc.org/data/ggd221) from the McMurdo Dry Valleys. The database includes site information, air and soil temperature measurements, soil profile features, and surface boulder weathering features. We have incorporated these data into a geographic information system (GIS) for addressing issues such as the distribution of soils along latitudinal and altitudinal gradients (Bockheim Reference Bockheim2008), whether or not high-level lakes existed in the McMurdo Dry Valleys (Bockheim et al. Reference Bockheim, Campbell and McLeod2008), and other issues.

Various kinds of glacier regimes have been identified in Antarctica, including polythermal glaciers that overrode the Transantarctic Mountains prior to 15 Ma and achieved wet-based conditions in deep troughs but yielded dry-based conditions at most high-elevation sites (Sugden et al. Reference Sugden, Denton and Marchant1991, Marchant et al. Reference Marchant, Denton and Swisher1993a, Reference Marchant, Denton, Sugden and Swisher1993b, Prentice et al. Reference Prentice, Bockheim, Wilson, Burckle, Hodell, Schlüchter and Kellogg1993, Stroeven & Kleman Reference Stroeven and Kleman1999, Denton & Sugden Reference Denton and Sugden2005, Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Marchant, Ashworth, Hemming and Machlus2007). Since the Miocene, polar conditions have existed in the Transantarctic Mountains, yielding a dry-based regime that includes alpine and outlet glaciers (Denton et al. Reference Denton, Sugden, Marchant, Hall and Wilch1993, Wilch et al. Reference Wilch, Denton, Lux and McIntosh1993, Prentice & Krusic Reference Prentice and Krusic2005, Staiger et al. Reference Staiger, Marchant, Schaefer, Oberholzer, Johnson, Lewis and Swanger2006, Atkins & Dickinson Reference Atkins and Dickinson2007). However, thicker portions of outlet glaciers occupying troughs may be wet-based. Grounding of ice in the Ross embayment has resulted in a third type of polar glacier that has deposited lake-ice conveyor deposits and “indicates a frigid environment with very little melt” (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Hendy and Denton2006).

The glacial thermal regime was estimated from the landform, sediment, and erosional features (Table I). Massive overriding of the Transantarctic Mountains from wet-based glaciers was identified by the presence of large-scale stoss and less topography, scablands, sub-glacial channel systems, glacial flow direction, and the existence of thin, irregular patches of silt-rich drift (Denton & Sugden Reference Denton and Sugden2005). Dry-based glaciers were identified from the presence of boulder-belt moraines with a sandy matrix texture in sharp contact with the underlying sediments or bedrock. Sediments from dry-based glaciers lack abundant glacial striations, polish, and moulding. Lake-ice conveyor deposits are typically stratified and massive and make up landforms such as mounds and moat line, cross-valley, and longitudinal ridges, moraine banks, and deltas and shorelines (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Hendy and Denton2006). We noted that although these deposits are from what is recognized as a polar glacier, they are not always dry-based.

Table I Evidence for differentiating dry-based from wet-based glaciers in Antarctica.

1Hall et al. 2000, Reference Hall, Hendy and Denton2006, Hendy et al. Reference Hendy, Sadler, Denton and Hall2000.

Buried soils were identified by lithologic (texture and provenance) discontinuities and sharp breaks in weathering parameters such as staining, presence of decomposed clasts (pseudomorphs or “ghosts”), salt morphology, and buried in situ desert pavements (Bockheim & Ackert Reference Bockheim and Ackert2007). Buried ventifacts resembling those on the surface were detected on the basis of having one to three, well developed, smooth, and broadly convex surfaces. In Antarctica ventifaction is strongly related to lithology, with diabase, sandstone, and quartzite most often featuring wind-abraded facets. However, other rock types such as diorite and dolerite may show ventifaction.

Soil pits were excavated to a depth of at least 100 cm, unless ice-cement or large boulders prevented this. Detailed soil descriptions were taken using standard techniques (Schoeneberger et al. Reference Schoeneberger, Wysocki, Benham and Broderson2002). Soil colours were taken with Munsell charts, and the colour-development equivalent was determined as the product of the coded hue and value (Buntley & Westin Reference Buntley and Westin1965). Soil textures were estimated in the field with c. 25% of these validated in the laboratory. The six-stage sequence of salt morphology developed by Bockheim (Reference Bockheim1990) was used; 0 = no visible salts, 1 = salt encrustations beneath clasts, 2 = salt flecks covering < 20% of the horizon area, 3 = salt flecks covering > 20% of the horizon area, 4 = weakly cemented salt pan, 5 = strongly cemented salt pan, and 6 = indurated salt pan. Soils were tested for carbonates with 10% HCl. The masses of stones (> 30 cm), cobbles (7.6–30 cm), and gravel (0.2–7.6 cm) were determined in the field.

Results and discussion

Distribution of soils in relation to glacial regime

Of the 590 pedons containing glacial materials of reasonably known glacial thermal regime, 480 (86%) were derived from dry-based glaciers (Table II). One of the characteristic features of the Transantarctic Mountains is the presence of boulder-belt or drop moraines in association with alpine glaciers and outlet glaciers such as the Taylor Glacier and the Ferrar Glaciers (Staiger et al. Reference Staiger, Marchant, Schaefer, Oberholzer, Johnson, Lewis and Swanger2006), respectively. For example, there are as many as 38 boulder-belt moraines ranging from 1–3 m in height that span the period 117 ka to 2.1–3.5 Ma in Arena Valley (Bockheim Reference Bockheim1982, Brook et al. Reference Brook, Kurz, Ackert, Denton, Brown, Raisbeck and Yiou1993) (Fig. 3). In the Hatherton Glacier region, there are as many as 16 boulder-belt moraines at some locations, which range from 10 ka to ∼2 Ma (Bockheim et al. Reference Bockheim, Wilson, Denton, Andersen and Stuiver1989) (Fig. 4). These moraines are up to 5 km long and commonly are 0.5–2.5 m high. They are comprised primarily of boulders and cobbles with a matrix of gravel and sand.

Table II Number of sites investigated at three regions in the Transantarctic Mountains by glacier regime. Number of sites with buried soils are shown in parentheses.

Fig. 3 Aerial photograph showing boulder-belt moraines in Arena Valley (77°50′S, 151°00′E).

Fig. 4 Aerial photograph showing boulder-belt moraines near Lake Wellman (79°55′S, 156°55′E) in the Hatherton Glacier area.

Our observations suggest that dry-based glaciers are able to drop boulder-belt moraines and isolated boulders over minimally disturbed landscapes. When observed in plan view, the boulder belts in some cases are separated by drift of the same age; in other cases the boulder belts overlie older drift. For example, in Arena Valley Quaternary-aged Taylor 3 and 4 boulder-belt moraines are separated by Miocene-aged Quartermain and Altar tills (Figs 3 & 6a).

Buried soils

There are 64 buried soils in our dataset (10% of total pedons). The majority (78%) of the pedons derived from glacial materials and containing buried soils are from dry-based boulder-belt moraines from the Taylor, Hatherton, and Beardmore glaciers. On the Bellum Platform in the Hatherton Glacier region (79°54′S, 155°15′E), we observed a sequence of buried soils beneath boulder-belt moraines that includes Britannia I over Britannia II, Britannia II over Danum, and Danum over Isca drift (Fig. 5). These drifts range from 10 ka to ∼2 Ma in age (Bockheim et al. Reference Bockheim, Wilson, Denton, Andersen and Stuiver1989).

Fig. 5 A chronosequence of buried soils on the Bellum Platform (79°54′S, 155°15′E) in the Britannia Range (Bockheim et al. Reference Bockheim, Wilson, Denton, Andersen and Stuiver1989).

Examples of buried soils are shown in Fig. 5. In Fig. 6a Taylor 4a drift of early Quaternary to late Pliocene age (Brook et al. Reference Brook, Kurz, Ackert, Denton, Brown, Raisbeck and Yiou1993, Marchant et al. Reference Marchant, Denton and Swisher1993b) buries Miocene-aged Quartermain 2 till in Arena Valley. An in situ diabase ventifact occurs in the desert pavement buried at 30 cm. In Fig. 6b from the Hatherton Glacier area, Isca drift with a possible age of 2 Ma (Bockheim unpublished) overlies pre-Isca drift. The buried pre-Isca drift has a desert pavement with in situ ventifacts and a thin saltpan with strongly oxidized soil at a depth of 35 cm. In Fig. 6c Asgard till (< 15.2, > 13.6 Ma; Marchant et al. Reference Marchant, Denton, Sugden and Swisher1993a) overlies Sessrumnir till (> 15.2 Ma) in Njord Valley of the Asgard Range. Asgard drift contains pulverulent (powdery) sandstone-rich material. The buried soil in Sessrumnir drift occurs at 50 cm and is derived primarily from dolerite. Most of the buried soils show an increase in colour development equivalent (CDE) compared with the overlying drift. Some of the pedons show an increase in salt morphology. Buried soils also may have sharp differences in clast size from overlying materials.

Fig. 6 Examples of buried soils in the Transantarctic Mountains: a. Pedon 75-19, Taylor 4b drift over/Quartermain 2 drift, Arena Valley (79°51′S, 160°59′E). The scale extends to 60 cm depth. A buried in situ ventifact occurs to the left of the scale half way down the photo. b. Pedon 78-33, Isca drift over pre-Isca drift, Lake Hendy area, Darwin Mountains (79°58′S, 156°19′E). The scale extends to 45 cm. The buried soil can be identified by the thin salt-rich, buried desert pavement (Db) underlain by a strongly stained Bwzb horizon. c. Pedon 83-22, Asgard drift over Sessrumnir drift, Njord Valley, Asgard Range (77°36′S, 161°07′E). Asgard drift contains pulverulent (powdery) sandstone-rich material. The buried soil in Sessrumnir drift occurs at 50 cm and is derived primarily from dolerite.

Buried soils are not limited to drift deposited by dry-based glaciers. Massive overriding of the Transantarctic Mountains during the Miocene by wet-based glaciers (Sugden et al. Reference Sugden, Denton and Marchant1991, Marchant et al. Reference Marchant, Denton and Swisher1993a, Reference Marchant, Denton, Sugden and Swisher1993b, Prentice et al. Reference Prentice, Bockheim, Wilson, Burckle, Hodell, Schlüchter and Kellogg1993, Stroeven & Kleman Reference Stroeven and Kleman1999, Denton & Sugden Reference Denton and Sugden2005, Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Marchant, Ashworth, Hemming and Machlus2007) has left buried soils. About a third (37%) of the buried soils were buried by non-glacial mechanisms, including wind and volcanic ash deposition, mass wasting, and fluctuation of lake levels.

Buried soils and recycled ventifacts are found in drifts ranging from the Last Glacial Maximum to Miocene (> 15 Ma) in age (Table III). They are especially prevalent in drifts from dry-based portions of outlet glaciers, which tend to be thin, ranging from < 1 to about 5 m in thickness. With each subsequent glacial advance, the drift with its soil mantle is either overridden by a dry-based glacier or is incorporated into the most recent drift. For this reason, a young drift may contain clasts that range from fresh to highly weathered. We have observed boulders with fresh striations etched into a strongly developed desert varnish. Similarly, we have noted clasts at the base of alpine glaciers that reveal previous weathering cycles and fragile weathering features, such as taffoni, entrained within dry-based glaciers. This phenomenon may lead to problems when cosmogenically dating boulders that are spatially in-between boulder-belt moraines.

Table III Age, thickness, number of pedons with recycled ventifacts, and solum thickness for drifts in the McMurdo Dry Valleys.

1 lQ = late Quaternary (< 0.13 Ma), m-lQ = late to middle Quaternary (0.13–0.30 Ma), mQ = middle Quaternary (0.30–0.79 Ma), e-mQ = early to middle Quaternary (0.5–1.3 Ma), eQ = early Quaternary (1.2–1.8 Ma), P = Pliocene (1.8–5.3 Ma), M = Miocene (5.3–24 Ma).

2Glaciation and age from Bockheim et al. (Reference Bockheim, Wilson, Denton, Andersen and Stuiver1989), Denton et al. (Reference Denton, Bockheim, Wilson, Leide and Andersen1989), Brook et al. (Reference Brook, Kurz, Ackert, Denton, Brown, Raisbeck and Yiou1993), Marchant et al. (Reference Marchant, Denton and Swisher1993b), Wilch et al. (Reference Wilch, Denton, Lux and McIntosh1993), Higgins et al. (Reference Higgins, Hendy and Denton2000b), Ackert & Kurz (Reference Ackert and Kurz2004), Hall & Denton (Reference Hall and Denton2005).

3 Till thickness: Marchant et al. (Reference Marchant, Denton and Swisher1993a, Reference Marchant, Denton, Sugden and Swisher1993b), Wilch et al. (Reference Wilch, Denton, Lux and McIntosh1993), Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Denton, Lux and SchlŰchter1997, Reference Hall, Denton and Hendy2000), Higgins et al. (Reference Higgins, Hendy and Denton2000b), Ackert & Kurz (Reference Ackert and Kurz2004), Hall & Denton (Reference Hall and Denton2005).

4 Solum thickness: Bockheim & McLeod (Reference Bockheim and McLeod2006), Bockheim & Ackert (Reference Bockheim and Ackert2007), Bockheim (Reference Bockheim2007), Bockheim et al. (Reference Bockheim, Campbell and McLeod2008).

5 Recycling ratio = mean till thickness (m), divided by mean solum thickness (cm).

Recycled clasts

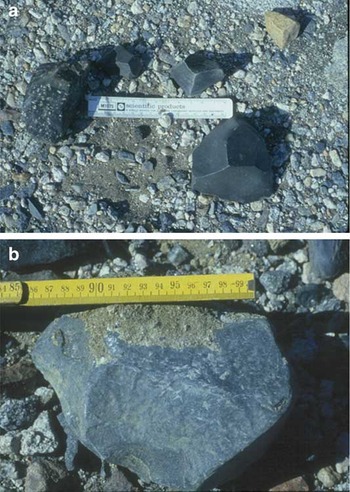

Eighteen percent of the pedons included in the dataset contain recycled and/or buried ventifacts. The majority (84%) of the pedons containing recycled ventifacts originated from dry-based glaciers (Table III). Examples of recycled ventifacts recovered from Pliocene-aged Onyx and Loop drifts (dry-based) in central Wright Valley (Hall & Denton Reference Hall and Denton2005) are shown in Fig. 7. In addition, numerous pedons contained highly varnished clasts below the zone of staining, providing further evidence of recycling of clasts, primarily by dry-based glaciers.

Fig. 7 Examples of recycled ventifacts recovered from a. Onyx drift (pedon 83-31), and b. Loop drift (pedon 83-33) in central Wright Valley. In both photos the scale is 15 cm in length.

Non-glacial mechanisms were involved in recycling clasts in less than 25% of the pedons, including wind sorting, mass wasting, and stream deposition.

To evaluate the influence of glacier regime on soil burial and clast recycling, we calculated the “recycling ratio”: the mean solum thickness to mean drift thickness for different-aged drifts in the McMurdo Dry Valley. Drift thicknesses and ages were determined from reports by Marchant et al. (Reference Marchant, Denton and Swisher1993a, Reference Marchant, Denton, Sugden and Swisher1993b), Wilch et al. (Reference Wilch, Denton, Lux and McIntosh1993), Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Denton, Lux and SchlŰchter1997, Reference Hall, Denton and Hendy2000), Higgins et al. (Reference Higgins, Denton and Hendy2000a), Ackert & Kurz (Reference Ackert and Kurz2004), and Hall & Denton (Reference Hall and Denton2005). Solum thickness, which includes only D and B horizons and not BC and C horizons, is based on data from Bockheim & McLeod (Reference Bockheim and McLeod2006), Bockheim (Reference Bockheim2007), Bockheim & Ackert (Reference Bockheim and Ackert2007) and Bockheim et al. (Reference Bockheim, Campbell and McLeod2008). We recognize that the recycling ratio is not a robust parameter as deflation of old deposits, prior to burial beneath younger tills, might reduce initial till thickness considerably (Bockheim & Ackert Reference Bockheim and Ackert2007). In addition material derived from hillslopes and carried along the glacier surface would be more apt to contain recycled ventifacts that material derived subglacially.

Recycling of ventifacts is most common where the recycling ratio is narrow (Table III), suggesting that thin drifts, especially those manifested by boulder-belt moraines, most commonly contain high amounts of recycled clasts. In thick drifts such as those in eastern Taylor and Wright valleys, any buried ventifacts would be “diluted” with unweathered clasts.

Conclusions

Buried soils and soils containing recycled ventifacts are common in the Transantarctic Mountains. Some of the soils contain burials with the desert pavement intact. These features are not limited to, but occur primarily in, boulder-belt moraines dropped by dry-based glaciers. Drifts containing recycled ventifacts and buried soils range from late Quaternary to Miocene in age, suggesting that a drift deposited by dry-based or wet-based glaciers may contain reworked clasts from several glaciations. These results have important implications for selection of boulders for cosmogenic dating. Using the “recycling index,” which is the ratio of mean solum thickness to mean thickness of a drift, a narrow ratio implies that the drift could contain a high proportion of recycled clasts.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs, Antarctic Division. More recent support was provided by Antarctica New Zealand. The author appreciates working with G.H. Denton and the field assistance of S.C. Wilson, M. McLeod and many other individuals. Three anonymous reviewers provided helpful/constructive comments for revizing this paper.