Introduction

This work provides the second contribution resulting from the Czech Geological Survey Antarctic research project focusing on fossil wood from the Upper Cretaceous of James Ross Island, lying to the east of the Antarctic Peninsula in the Larsen Basin (Kvaček & Sakala Reference Kvaček and Sakala2012, Sakala & Vodrážka Reference Sakala and Vodrážka2014). During the January–February 2010 field season, almost 350 specimens of fossil wood were collected. The majority of the specimens originated from the vicinity of Brandy Bay and the area between Johann Gregor Mendel Czech Antarctic Station (63°48′5.6″S, 57°53′5.6″W) and Crame Col, situated in the northern part of James Ross Island (Fig. 1). The stratigraphic range covered by these fossils extends from the mid-Albian (base of the Whisky Bay Formation) through the Hidden Lake Formation (Coniacian) into the lower part of the Santa Marta Formation (uppermost Coniacian-Santonian), so the fossil wood represents a stratigraphically well-defined source of information. Previous studies of fossil wood from James Ross Island (Francis & Poole Reference Francis and Poole2002, Cantrill & Poole Reference Cantrill and Poole2005, Sakala & Vodrážka Reference Sakala and Vodrážka2014, Pujana et al. Reference Pujana, Raffi and Olivero2017, Reference Pujana, Iglesias, Raffi and Olivero2019) prove that this region was forested during the Early-Late Cretaceous crossover, which was possible due to the warm and humid climatic conditions prevalent then.

Fig. 1. a. Map showing the location of the James Ross Island region. Geological sketch map of the area in the box is shown in Fig. 1b. b. Geological sketch map of James Ross Island showing the Gustav, Marambio and Seymour island groups for the James Ross Island region. The area in the box is shown in more detail in Fig. 1c. c. Enlargement of the Cretaceous sediments outcropping in the north-western James Ross Island with the locality yielding the studied wood indicated. The dashed lines trace formation boundaries across sea and ice cover; modified from fig. 1 in Sakala & Vodrážka (Reference Sakala and Vodrážka2014).

Material and methods

Every sample of fossil wood was documented in the field during the 2010 season, including the regular use of the so-called ‘reference points’, to which GPS coordinates and lithological and stratigraphic data were attributed. Care was taken to preserve the identity of specimens. If specimens seemed to be splinters originating from one original piece of wood simply lying in close proximity, then the same sample number was given to all such pieces, suffixed by a letter.

Thin sections ~40 μm thick were prepared following standard techniques in three basic sections: transverse (TS), tangential longitudinal (TLS) and radial longitudinal (RLS). They were studied and photographed using optical microscopes (Olympus BX-51) in normal transmitted light. All measurements were made using Quick PHOTO MICRO 3.0 software. The anatomical description is in accordance with the IAWA Softwood List (IAWA Committee 2004). The research described a new genus of fossil wood, based on the first finding of this type of wood: specimen AN40. All specimens, as well as the corresponding thin slides, are housed in the Czech Geological Survey in Prague, Czech Republic.

Geological setting

The James Ross Basin contains a Mesozoic-Cenozoic sequence in the James Ross Island area (Fig. 1a), and it is interpreted as a small part of a larger sedimentary basin, Larsen Basin, which developed in Jurassic times as a result of continental rifting during the early stages of the Gondwana break-up (Hathway Reference Hathway2000 and references therein).

The silicified wood under study here (AN40d) is one of four splinters (AN40a–d), which all come from one sample (AN40), representing one small trunk. The fossil wood was collected from the extensive Lower-Upper Cretaceous sedimentary sequence exposed on the western and north-western margins of James Ross Island (Fig. 1b). This sequence comprises part of a regressive mega-sequence of volcanic arc-related clastic and volcaniclastic marine rocks, which has now been extensively studied and subdivided lithostratigraphically (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Pirrie and Crame2006 and references therein). The specimen was collected from the Lewis Hill Member of the Whisky Bay Formation (63°50′52.0″S, 58°00′59.4″W) of the Gustav Group (Fig. 1c), at reference point A43.

The Whisky Bay Formation consists of 720–950 m of clast-supported conglomerates and pebbly sandstones, interbedded with finer-grained sandstones and silty mudstones, representing a slope-apron and submarine fan deposit (Ridding & Crame Reference Ridding and Crame2002 and references therein). The Lewis Hill Member, at 552 m thick, is one of the three members of the Whisky Bay Formation, and it is characterized by various intercalations of mudstones, sandstones and pebble conglomerates (Crame et al. Reference Crame, Pirrie, Ridding, Francis, Pirrie and Crame2006). Crame et al. (Reference Crame, Pirrie, Ridding, Francis, Pirrie and Crame2006) also examined the mid-Cretaceous stratigraphy of the James Ross Basin using new macrofaunal and palynological data, the overlap of which indicates a late Albian age for the Lewis Hill Member.

Systematic palaeobotany

Order: Unknown.

Genus: Mixoxylon Chernomorets & Sakala, gen. nov.

Type species: Mixoxylon australe Chernomorets & Sakala, sp. nov. (Figs 2–5).

Fig. 2. Percentage of rays according to their height in Mixoxylon australe (based on holotype AN40d, slide 47 868).

Fig. 3. Sketch of a radial longitudinal section of Mixoxylon australe (based on holotype AN40d, slide 47 867): A = Abietineentüpfelung (distinct pitting of horizontal and tangential ray walls); AP = araucarioid cross-field pitting; EWT = earlywood tracheids; LWT = latewood tracheids; PP = podocarpoid cross-field pitting; R = rays; SP = scalariform pitting.

Fig. 4. Mixoxylon australe (holotype AN40d and transverse thin section): a. three consecutive growth rings (arrows show boundaries between growth rings) (47 866); b. sample AN40a, macroscopic view; c. macroscopic view of holotype AN40d.

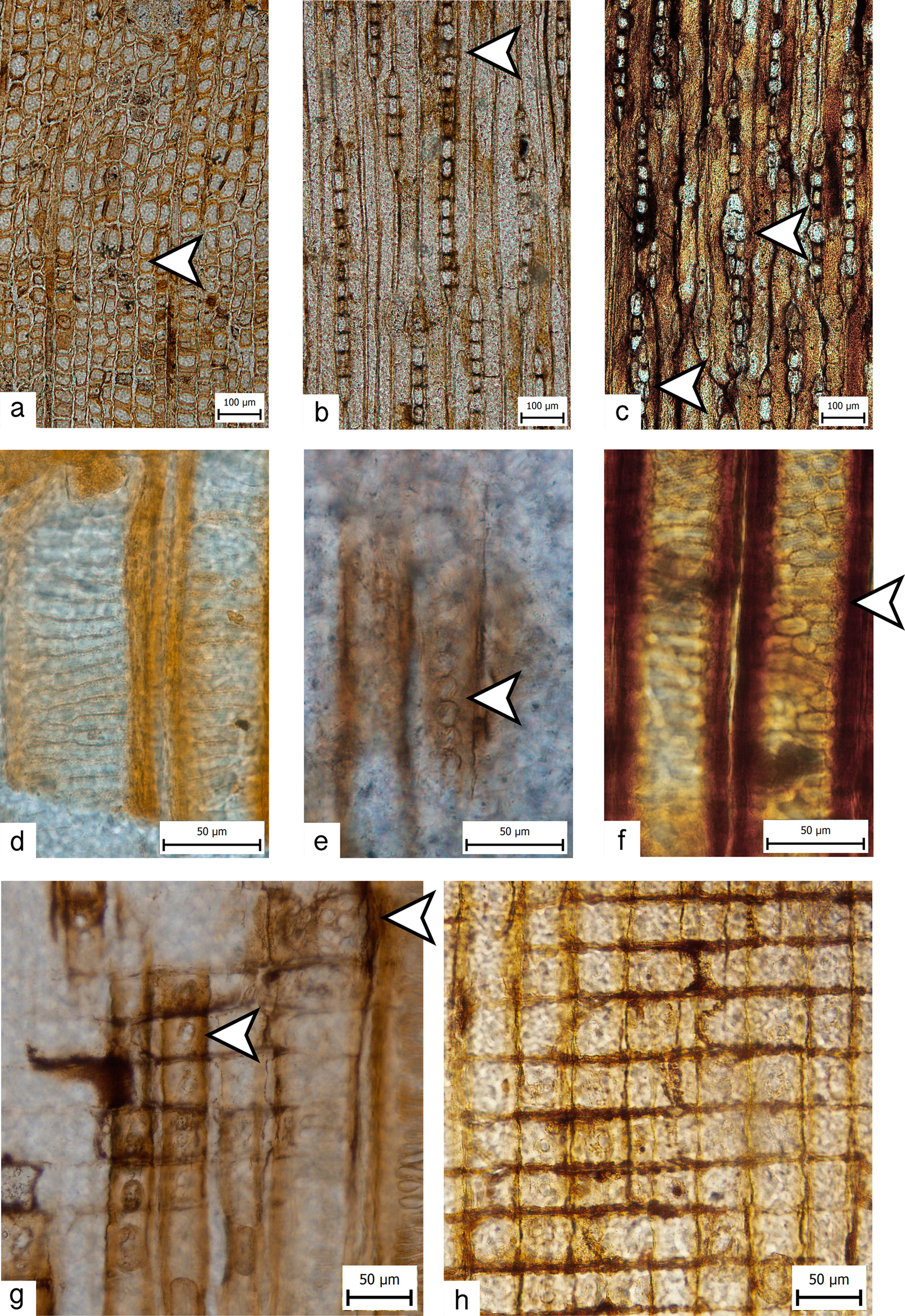

Fig. 5. Mixoxylon australe (holotype AN40d, three thin sections: 47 866 (transverse section; TS), 47 867 (radial longitudinal section; RLS), 47 868 (tangential longitudinal section; TLS)): a. growth ring boundaries (arrow) (TS); b. & c. very low to very high (2–35 cells) rays with few partly biseriate portions (arrows) (TLS); d. earlywood tracheids with scalariform pitting (RLS); e. araucarian pitting in the radial walls of latewood tracheids (arrow) (RLS); f. intermediate pitting in the radial walls of latewood tracheids (arrow) (RLS); g. araucarioid (top-right arrow) to podocarpoid (middle arrow) cross-field pitting (RLS); h. tangential and horizontal walls of ray parenchyma cells with distinct pitting (Abietineentüpfelung sensu Kräusel) (RLS).

Derivation of name: Named for the friend and head of the geological part of the Czech Antarctic project Petr Mixa; the name also points to a ‘mixed’ character of features, situated between Sahnioxylon Bose & Sah and Phoroxylon Sze.

Plant Fossil Names Registry Number (for new genus): PFN001850.

Generic diagnosis: Growth ring boundaries are indistinct, with the earlywood zone significantly wider than the latewood zone. Earlywood tracheids are characterized by scalariform pitting in radial walls. The latewood tracheid pitting in radial walls ranges from araucarian to an intermediate type. Cross-field pitting is araucarioid to podocarpoid. Tangential and horizontal walls of ray parenchyma cells both have distinct pitting (Abietineentüpfelung sensu Kräusel). Axial parenchyma and resin canals are absent. Rays are exclusively uniseriate.

Mixoxylon australe Chernomorets & Sakala, sp. nov.

Derivation of name: The ‘australe’ points to the southernmost occurrence of this type of wood.

Plant Fossil Names Registry Number (for new species): PFN001851.

Holotype designated here: Sample AN40d and three thin sections: 47 866 (TS), 47 868 (TLS) and 47 867 (RLS) (Figs 4 & 5).

Repository: The holotype is deposited in the palaeontological collections of the Czech Geological Survey.

Type locality: Western side of Bandy Bay, James Ross Island, locality A43 (63°50′52.0″S, 58°00′59.4″W) (Fig. 1c).

Stratigraphic horizon: Whisky Bay Formation, Lewis Hill Member, Lower Cretaceous, upper Albian.

Occurrence: known only from the type locality.

Specific diagnosis: Growth ring boundaries are indistinct, with a significantly wider earlywood zone than latewood zone; transition from earlywood to latewood is gradual. Earlywood tracheids are characterized by scalariform pitting in radial walls. The latewood tracheid pitting in radial walls ranges from araucarian to an intermediate type, with crowded pits. Cross-field pitting is araucarioid to podocarpoid, with predominance of the araucarioid type. There are 2–10 pits per cross-field, which are variable in size. Tangential and horizontal walls of ray parenchyma cells both have distinct pitting (Abietineentüpfelung sensu Kräusel). Axial parenchyma and resin canals are absent. Rays are exclusively uniseriate.

Macroscopic description: Petrified wood, preserved by calcite permineralization and light yellow to light brown in colour. The size of the biggest sample, AN40a, is 17.6 cm high, 13.5 cm wide and 8 cm long (Fig. 4b). The size and curvature of the growth rings (Fig. 4b & c) allow us to conclude that the samples (i.e. AN40a–d) come from a trunk, estimated to be 20–25 cm in diameter. The samples are well preserved.

Microscopic description: Transverse section: Growth ring boundaries are indistinct (Figs 4a & 5a), with a distinctly wider earlywood zone than latewood zone in the three observed growth rings; transition from earlywood to latewood is gradual. Tracheids are arranged in parallel radial rows, and their diameter does not change significantly. Their outline is polygonal to hexagonal in shape. The radial diameter of earlywood tracheids is 24–54 μm (mean value is 38 μm) and the wall thickness is 2–10 μm; the radial diameter of latewood tracheids is 23–50 μm (mean value is 33 μm) and the wall thickness is 5–18 μm (n = 30); tangential diameter of tracheids ranges from 24 to 84 μm (n = 40). Tangential longitudinal section: Rays are very low to very high (2–35) numbers of cells high and exclusively uniseriate, with a few rays that are partly biseriate (Fig. 5b & c). Most rays (15%) are medium (9) numbers of cells high (Fig. 2) (n = 134). There are 2–13 rays per tangential millimetre (mean value is 7) (n = 16). Pitting in tangential tracheids is poorly visible. Rays are exclusively homogeneous (i.e. without ray tracheids; Fig. 5h), and their marginal cell(s) are usually insignificantly higher than the central ones (Fig. 5b & c). Radial longitudinal section: Earlywood tracheids are characterized by scalariform pitting (Fig. 5d); latewood tracheid pitting in radial walls ranges from araucarian to an intermediate type (partway between araucarian and scalariform), with uniseriate to triseriate crowded pits (Fig. 5e & f). Cross-field pitting is araucarioid to podocarpoid, sometimes cupressoid; pits are predominantly araucarioid in earlywood tracheids and podocarpoid in latewood ones (Fig. 5g). There are 2–10 pits per cross-field, which are variable in size. Tangential and horizontal walls of ray parenchyma cells both have distinct pitting (Abietineentüpfelung sensu Kräusel) (Fig. 5h). Axial parenchyma and resin canals, idioblasts and storied tracheid tips are all absent.

Discussion

According to Philippe & Bamford (Reference Philippe and Bamford2008) and Philippe et al. (Reference Philippe, Cuny and Bashforth2010), there are five fossil homoxylous genera with scalariform pitting: Ecpagloxylon Philippe et al., Lhassoxylon Vozenin-Serra & Pons, Phoroxylon Sze, Sahnioxylon Bose & Sah and Scalaroxylon Vogellehner. The studied fossil wood cannot belong to Lhassoxylon due to the absence of axial parenchyma and resin canals (Vozenin-Serra & Pons Reference Vozenin-Serra and Pons1990). We cannot consider the studied wood to be Scalaroxylon (Vogellehner Reference Vogellehner1967) because our fossil has distinct pitting on both the horizontal and tangential walls of ray parenchyma cells (Abietineentüpfelung sensu Kräusel; see Mantzouka et al. Reference Mantzouka, Karakitsios and Sakala2017, p. 78). Nor can it belong to Ecpagloxylon - the wood specimens in this research have homogenous wood (tracheids similar in size and shape within two neighbouring radial rows), Abietineentüpfelung, exclusively uniseriate rays and absence of axial parenchyma, idioblasts or storied tracheid endings (Philippe et al. Reference Philippe, Cuny and Bashforth2010). The fossil genus Sahnioxylon is characterized by sharply marked growth rings, with a more developed latewood zone than earlywood zone, earlywood tracheids with scalariform pitting, latewood tracheids with uniseriate to multiseriate pitting in radial walls and one to four seriate rays (Bose & Sah Reference Bose and Sah1954, Lemoigne & Torres Reference Lemoigne and Torres1988, Philippe et al. Reference Philippe, Torres, Zhang and Zheng1999). Unlike Sahnioxylon, our wood has a strongly developed earlywood zone (i.e. significantly higher percentage of earlywood in comparison with latewood; Fig. 4a) and exclusively uniseriate rays. Finally, Phoroxylon is the most similar to the studied wood, in having earlywood tracheids with scalariform pitting, latewood tracheids with araucarian crowded pits in radial walls, exclusively uniseriate rays, two to six crowded pits per cross-field, horizontal walls of ray parenchyma cells with distinct pitting and distinct growth rings. However, Phoroxylon has a more developed latewood zone than earlywood zone. In addition, as Bose & Sah (Reference Bose and Sah1954), Sze (Reference Sze1954), Lemoigne & Torres (Reference Lemoigne and Torres1988) and Philippe et al. (Reference Philippe, Torres, Zhang and Zheng1999) consider a wider latewood zone for Phoroxylon and Sahnioxylon to be an essential characteristic for both genera, we cannot attribute sample AN40 to either of them. Based on this distinctive wood anatomy, we propose a new fossil genus Mixoxylon gen. nov. for this type of fossil wood with intermediate characteristics between these two fossil genera (Figs 3–5).

The systematic affiliation of Phoroxylon and Sahnioxylon is still unclear. In recent decades, some authors maintain that they belong to bennettitalean gymnosperms (Lemoigne & Torres Reference Lemoigne and Torres1988, Falcon-Lang & Cantrill Reference Falcon-Lang and Cantrill2001, Poole & Cantrill Reference Poole and Cantrill2001); other authors think they represent an evolutionary transitional type and ancestral plant of angiosperms without vessels (see Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Wang, Tian, Xie, Zhang, Li and Huang2019). The studied fossil wood is homoxylous and pycnoxylic. Moreover, the absence of vessels and exclusively uniseriate rays allows us to assign Mixoxylon to conifer-like wood. Unlike Sahnioxylon or Bucklandia A.T. Brongniart, its wood anatomy does not resemble that of cycad or bennettitalean stems because of the presence of exclusively uniseriate rays and a well-developed earlywood zone in growth rings, or in other words the general absence of manoxylic wood with abundant parenchyma cells and large and well-developed pith (Bose Reference Bose1953, Greguss Reference Greguss1968, Cantrill Reference Cantrill2000, Jud et al. Reference Jud, Rothwell and Stockey2010). Based on the abovementioned characteristics and overall similarity to conifers, we tentatively rank Mixoxylon among conifers. On the other hand, we cannot exclude a possible relation to some ‘pycnoxylic seed fern’, the wood of which is as yet unknown. As a whole, a clear systematic affiliation is not possible without further finds, where a closer or even organic association with leaves or reproductive organs will be present.

The Mixoxylon wood is different from earlier finds of fossil wood from the James Ross Island region (Cantrill & Poole Reference Cantrill and Poole2012, Sakala & Vodrážka Reference Sakala and Vodrážka2014, Pujana et al. Reference Pujana, Raffi and Olivero2017, Pipo et al. Reference Pipo, Iglesias and Bodnar2020), and its systematic position is not yet clear, even though we must note once again its similarity to Phoroxylon and Sahnioxylon woods. The occurrence of Phoroxylon is limited to the Northern Hemisphere, but previous finds of Sahnioxylon, with one Middle Jurassic exception from Liaoning, China (Philippe et al. Reference Philippe, Torres, Zhang and Zheng1999), were recorded in the Antarctic Peninsula and India (Bose & Sah Reference Bose and Sah1954, Lemoigne & Torres Reference Lemoigne and Torres1988, Philippe et al. Reference Philippe, Torres, Zhang and Zheng1999, Falcon-Lang & Cantrill Reference Falcon-Lang and Cantrill2001, Poole & Cantrill Reference Poole and Cantrill2001). This may indicate a common origin of these two taxa. In addition, the new find of Mixoxylon from James Ross Island represents the southernmost record of fossil gymnosperm wood with at least partly scalariform pitting in radial tracheid walls (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Mesozoic woods with at least some scalariform tracheid pitting (based on the table by Philippe et al. Reference Philippe, Cuny and Bashforth2010).

Finally, the difference in growth rings between the earlywood and latewood zones in Sahnioxylon was described both by Lemoigne & Torres (Reference Lemoigne and Torres1988) and Philippe et al. (Reference Philippe, Torres, Zhang and Zheng1999) as ‘endogenous’, related to the plant itself, and not ‘exogenous’, related to a specific adaptation strategy to the environment or climate. According to Lemoigne & Torres (Reference Lemoigne and Torres1988), a strongly developed earlywood zone, together with larger rays, indicates deciduous foliage and an active growing process at the beginning of the vegetation period. Given the fact that Mixoxylon and Sahnioxylon with different growth rings and rays lived in the same type of Early Cretaceous climate - warm, humid and with summer temperatures from 20°C to 24°C and winter temperatures not decreasing below 0°C (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Ashworth, Cantrill, Crame, Howe, Stephens, Cooper, Barrett, Stagg, Storey, Stump and Wise2008, Cantrill & Poole Reference Cantrill and Poole2012) - we cannot expect the same adaptation strategy and/or type of foliage for them.

Conclusions

The new southernmost gymnosperm wood with scalariform tracheid pitting, Mixoxylon australe Chernomorets & Sakala gen. et sp. nov., from the Whisky Bay Formation on James Ross Island cannot be accurately classified without further finds. However, we propose that Mixoxylon represents a conifer based on such anatomical features as earlywood tracheids with scalariform pitting, latewood tracheid pitting in radial walls ranging from araucarian to an intermediate type, exclusively uniseriate rays and a well-developed earlywood zone in the growth rings. Given this combination of characteristics, Mixoxylon and Sahnioxylon Bose & Sah represent two homoxylous types of wood with scalariform pitting from the Antarctic region. This observation allows us to potential gain a better understanding of the biodiversity and various adaptation strategies in the specific palaeoenvironmental conditions of high-latitude regions during a greenhouse type of climate, for which we have no modern analogues today.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marc Philippe and an anonymous reviewer for their remarks. We would also like to thank Petr Daneš for proofreading the English language of the latest version of the manuscript.

Author contributions

OC prepared the wood anatomy description, discussion, conclusions and all figures; JS worked on geological setting, supervision of wood anatomy and nomenclature and discussion (partly).

Financial support

This work was undertaken with the financial support of the Czech Geological Survey (grant No. 310380). The research was also partly supported by grants from Charles University (Progress Q45 and SVV).

Details of data deposit

The holotype AN40d and the three corresponding thin sections - 47 866 (TS), 47 868 (TLS), 47 867 (RLS) - are all deposited in the palaeontological collections of the Czech Geological Survey in Prague.