INTRODUCTION

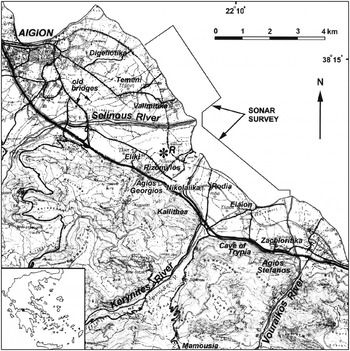

Helike, the principal ancient city of Achaea on the south-western coast of the Gulf of Corinth, was founded in the Bronze Age and destroyed by an earthquake and tsunami in 373 bc. This remarkable catastrophe was reported by many ancient sources both contemporary with the event and later, down to Late Antiquity (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou2005a). Geoarchaeological investigations to locate the ancient city were carried out by The Helike Project between 1988 and 2000, first underwater and from 1991 onwards on dry land in the coastal plain 7 km south-east of Aigion (Fig. 1). Archaeological excavations since 2000 have been very fruitful and have brought to light, mainly in the broad zone between the Selinous and Kerynites rivers, rich ancient remains covering a long chronological range from the Early Bronze Age down to late Byzantine times. The work has also provided abundant data on geomorphological changes which have affected the Helike plain from prehistoric times.

Fig. 1. The environs of the Helike search area, including the 1988 sonar survey. Asterisk and letter R indicate the location of the Rizomylos Early Helladic site. From the Greek Army Geographic Service 1:50,000 map.

Geoarchaeological work conducted in the centre of the plain, in the area of modern Rizomylos (Fig. 1, R), led to the unexpected discovery of a planned Early Bronze Age coastal town. Rich archaeological finds such as potsherds, burnt bone, charcoal and sun-dried clay fragments, found in samples recovered from borehole B75, drilled in 1998 at Rizomylos, led to the inclusion of this location among the first to be tested by excavation in the year 2000 (Soter and Katsonopoulou Reference Soter and Katsonopoulou2005). Unexpectedly, in test trench H7, opened near borehole B75 (Fig. 2) to investigate and identify the borehole data, significant architectural remains and associated pottery dated to the Early Bronze Age (EBA) period were discovered at a depth of 3–4 m below the surface (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou2005b, 38–9, 56–7 figs 22, 23 and 24). Continuing excavations in this area between 2001 and 2011 brought to light, in a total of nine trenches (H7, H21, H22, H26, H38, H43, H51, H61 and H65) (Fig. 3), the well-preserved remains of an extensive coastal Early Helladic (EH) II–III centre, built once on a low hill (about 3 m high), only a few hundred metres from the sea. In fact, it lay on the seaward side of a lagoon which has existed intermittently in this part of the plain from the Late Neolithic period (Soter and Katsonopoulou Reference Soter and Katsonopoulou2011; Koutsios Reference Koutsios2009). Combined data from our geoarchaeological work and excavations suggest that the settlement occupies a territory of about 30 ha. A number of boreholes drilled in the area have shown expansion of the buried EH occupation horizon further to the north and south-west of the excavated trenches (Soter and Katsonopoulou Reference Soter and Katsonopoulou2011, 589, 592, 588 fig. 3; The Helike Project Archives 2011, 2012). Also, further east and south-east, more structures were detected via geophysical investigations using electrical resistivity tomography, buried at depths corresponding with the EH buildings found in the excavated trenches and lying under the discovered Roman road through the area (Tsokas et al. Reference Tsokas, Tsourlos, Stampolidis, Katsonopoulou and Soter2009, especially 257 fig. 7, 258 fig. 8, 260 fig. 10 and 262 fig. 12: locations H21 and H51). Analysis and radiocarbon dating on material retrieved from boreholes drilled in the area of the settlement and inside trench H61 have revealed that occupation actually extends back as early as EH I (see core HEL 22 in Engel et al. Reference Engel, Jacobson, Boldt, Frenzel, Katsonopoulou, Soter, Alvarez- Zarikian and Brückner2016, 7–8, 9 fig. 4; Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 65 fig. 2, 72).

Fig. 2. Composite stratigraphic profile from borehole B75 and trench H7 in the Rizomylos Early Helladic site. MSL indicates mean sea level c.1950 (from Alvarez-Zarikian, Soter and Katsonopoulou Reference Alvarez-Zarikian, Soter and Katsonopoulou2008, 121 fig. 6).

Fig. 3. Plan of archaeological trenches excavated in the Rizomylos Early Helladic site between 2000 and 2011.

Excavation data have shown that the EBA settlement was destroyed by an earthquake, accompanied by fire, and was immediately abandoned, thereby leaving its contents intact, sealed under thick clay deposits (Fig. 4). Environmental analysis of sediments covering the EH ruins showed a mixture of freshwater, brackish and marine microfauna, indicating that the site was buried under the sediments of a lagoon (Alvarez-Zarikian, Soter and Katsonopoulou Reference Alvarez-Zarikian, Soter and Katsonopoulou2008), which in fact protected it from subsequent human intervention, such as is commonly the case at other prehistoric sites, which have continued to be used over many centuries with consequent repairs to and reshaping of the earlier buildings. Subsequent sedimentation and uplift resulted in the re-emergence of the surrounding area as dry land (Soter and Katsonopoulou Reference Soter and Katsonopoulou2011), reoccupied in the Hellenistic–Roman periods as indicated by the presence of Hellenistic remains and a main Roman road in this area (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou, Kissas and Niemeir2013; Tsokas et al. Reference Tsokas, Tsourlos, Stampolidis, Katsonopoulou and Soter2009).

Fig. 4. Stratigraphy of the east side in trench H38 representing the 3 m silt/clay deposits on top of the EH ruins (The Helike Project 2002).

ARCHITECTURE AND THE METAPHORS OF POWER

Buildings and individual features

The architectural remains of EH Helike have been exposed in nine excavation trenches measuring 10 × 5 m within the broader area of about 30 ha occupied by the site. They belong to a sequence of stratified occupation phases of EH II–III, the final one dating to early EH III, bringing to an end the long sequence of continuous rebuilding witnessed at the site over generations in the mid-third millennium bc. In this final phase, on which this article focuses, the town consisted primarily of large rectangular buildings arranged along cobbled streets and following an overall architectural plan. In terms of specific house plans, however, we should note the exception of at least one apsidal structure partly unearthed in one of the trenches (H22 Building 3, Fig. 5). However, the latest phase of the settlement as an organised town seems to have emerged as a result of an extensive reorganisation following a formal plan structured on the basis of square insulae, where the long rectangular buildings would generally be oriented north–south and east–west, alongside cobbled streets and open paved areas (see especially plans of H22, H43 and H51, Fig. 3). There is evidence that the town was probably surrounded by a fortification, given that one of the walls, revealed in the southernmost part of the two adjacent trenches H7 and H21, reaches a width of 3.50 m, and is probably within the size range for an enclosure wall indicating the boundary of the town at this location.

Fig. 5. Plan of trench H22. Diamonds indicate the finding spots of the depas cup in Building 2 and of gold and silver items in Building 3 (from Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 79 fig. 16).

In terms of their interior spatial arrangement, the buildings discovered form groups of a number of spacious rooms, including areas specifically designed for food preparation and storage served by a good number of large pithoi (some of them arranged in fixed positions inside the house plan) for the long-term storage of agricultural products and supplies. In one of the trenches (H61), workshop areas for tool manufacture were also found. Generally, the walls of the buildings uncovered are preserved above the lower foundation level to a height of 0.30–0.40 m, although in several cases they reach 0.60 m high, and in one case (H65) almost the height of 1 m. Their width usually ranges between 0.40 m and 0.60 m, although a significant number of walls are 0.70–0.80 m wide (H43, H51, H61, H65); in certain cases they may reach or even exceed 1 m, as in trench H61, where one of the earliest walls dated to the EH II period is 1.25 m wide.

The wall construction technique follows the standard building conventions observed on the mainland throughout the EBA and beyond (Wiencke Reference Wiencke2000; Banks Reference Banks2013; Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 194), regardless of the size, scale and organisation of the sites. Foundations at Helike are made of cobblestones and are built according to two basic types: (a) two rows of larger stones set lengthwise with smaller stones in the middle, (b) four rows of stones of the same size or with smaller stones in the middle two rows. Certain walls show herringbone masonry (Cosmopoulos Reference Cosmopoulos, Laffineur and Basch1991, 156). The upper part of the walls was built with sun-dried mud bricks coated with clay, as witnessed by a good number of clay lumps and wall fragments excavated in various trenches. The building material employed shows that in the construction of the houses local stone types were mainly used: grey limestone, red, green and orange psammite, grey conglomerate and, less commonly, reddish-brown chert (Doutsos and Piper Reference Doutsos and Piper1990; Xypolias and Doutsos Reference Χypolias and Doutsos2000; Koukouvelas et al. Reference Koukouvelas, Stamatopoulos, Katsonopoulou and Pavlides2001). More rarely, black dolomite originating from the adjacent region of Arcadia (Xypolias and Koukouvelas Reference Xypolias and Koukouvelas2001; Trikolas and Alexouli-Livaditi Reference Trikolas and Alexouli-Livaditi2004) was procured as a special choice for building walls at Helike.

Paved streets and house floors

The town had open areas for circulation and gathering, with carefully paved surfaces, as indicated by the cobbled streets revealed in three of the trenches excavated so far (H22, H43, H51, Fig. 3); their sides were flanked by large rectangular buildings and in one case (H22) by an apsidal building as well. The streets run both north–south and east–west following the square grid of the settlement and their width ranges 1.20–2.50 m. One of them, in trench H22, running north–south seems to terminate at its southern end in an open cobbled area, perhaps a square, which extends to its west. This street is bisected by another running east–west, flanked to the north by the apsidal Building 3 and to the south by the rectangular Building 1 (H22, Fig. 5).

In terms of building interiors, an exceptional number of paved floors were revealed inside the buildings. Well-preserved parts of floors, made of small to medium size pebbles and/or small cobbles, were discovered in four excavation trenches (H21, H43, H51, H61). More specifically, part of a paved floor made of fine, grey pebbles can be taken as representative for the whole of the floor surface of the house lying in H21, whereas in H51 the preserved part of an exquisite pebble floor of carefully selected small, black and red-brown chert pebbles reveals a very sophisticated taste in home decor and a quite demanding level of skilled craftsmanship. Trench H61, however, is even more extraordinary in preserving a striking number of interior paved floors made in almost every different size of pebble and cobble from small to medium to large, and associated with all the building phases discovered in the trench. Of these floors, basically of light-grey pebbles, seven date to the EH III period (upper level), three to the transitional II–III period (middle level) and five to the EH II period (lower level) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Plan of trench H61 with EH walls and preserved pebbled floors (The Helike Project 2007).

The rise of the private in an urban context

The remains discovered demonstrate that the site hosted a sequence of superimposed occupation phases in EH II, continuing into the next phase with a flourishing town of early EH III, which had developed public and private architecture, including the construction of buildings using advanced plans and techniques, and the storage of conspicuous wealth, goods and provisions. The indications of centralised functions, craft specialisation and the emergence of elites in EH Helike generally illustrate the proto-urban character of the settlement and the central economic and social role it seems to have played on the south-western coast of the Gulf of Corinth.

The extent, in the final settlement phase of Helike, of open areas between the building plots and their alignment in accordance with the long houses laid out on the square grid are strongly indicative of the interplay between communal and private interests in the town's architectural strategies. The new settlement plan emphasises the display of private houses overlooking wide paved streets, and displaying increased wealth and prestige within. And although our picture of the full social make-up of the town is not yet complete, we may argue that the coexistence of rising and competitive private sodalities, probably indicating that the town was not necessarily governed via a central or hierarchical scheme, finally functioned to produce a strongly cohesive communal value and prestige. The development of Helike, at the transition from EH II to III, into a formally organised town may indeed reveal the final result of internal social transformations which had long been developing in the context of the very particular line of interaction between town space, on the one hand, and the house as an emerging institution, on the other. In the Greek mainland, these transformations were set on course at the end of the Neolithic (Renfrew Reference Renfrew1972; Tomkins Reference Tomkins2004; Wright Reference Wright2004), and mark a gradual change in society, against the background of inter-household and inter-individual competition and community-based priorities attested in the Greek Neolithic. We may, then, infer a gradually increasing emphasis on the private during the transition from the earlier phases of settlement at EH Helike which achieved its most marked expression during the final phase in EH III.

Indeed, in terms of the indoor sphere, the elaborate pavements seem to have been part of an old tradition of house design and fashion at Helike since EH II. Their occurrence in various buildings of the final phase across the settlement indicates that house styles ran in parallel at this stage, and that at any one time a room could be modified according to the personal taste of its residents, their identity or symbolic expression, or even their degree of access to unusual raw material and maybe also to skilled labour. These factors seem to have been driven mainly by personal taste and special meanings rather than by simply functional, economical or physical priorities. With regard to the social context, these elements of sophistication may arise from the private within the competitive inter-household/house arena, and had probably played this role constantly since the earlier settlement phases in Helike. For this reason, they do not provide a clear-cut statement about the social transformations observed in the settlement all the way through to EH III, the larger-scale modifications being a feature only of the final phase in EH III.

The Corridor House

Let us now turn to the most significant element in our assessment, namely the Helike Corridor House (HCH), whose architectural remains were discovered mainly in trench H38 (Fig. 7) and partly in H43. In the trenches excavated, the western part and central sections of the building have been revealed; the corridors assumed to mirror the plan along the east side as well would extend into the next private field beyond the limits of the excavation. In trench H38, the part of the HCH exposed consists of two narrow, side corridors preserved on the western long side; the southern corridor measures 2.25 × 1.20 m, and the northern 3.10 × 1.80 m. The middle part of the southern narrow corridor is occupied by a platform almost square in shape, measuring 0.75 × 0.65 m, constructed of successive layers of large pottery fragments and flat cobblestones; it belonged to the final occupation phase of the building. Part of a central tripartite area came to light to the east of the corridors, its continuation extending outside the trenches, under neighbouring properties. Several complete or half-complete vessels were recovered from this area, especially in the south-western part of the house and along the northern wall, including two black tankards, at least three black and deep Bass bowls, a one-handled cup, one jug, and fragments from cooking pots, pithoi and other vessels, alongside a light-coloured jar with a narrow low collar and horizontal handles, and one broad-mouthed jar (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7. Architectural remains of the Helike Corridor House excavated in trench H38 (The Helike Project 2002).

Fig. 8. Cups, Bass bowl, pyxis, tankards, jug, amphora and pithos jar from the interior of the Helike Corridor House (photo: S. Katsarou).

In the rest of the southern part of the building, revealed in the adjacent trench H43 excavated to the south of H38, was found a large, specially made storage area containing a group of at least three big pithoi, over 1 m high (Fig. 9), standing along one of the walls. The rest of the room was packed with a great number of smaller black-burnished jars and tableware, many of them preserved complete or half-complete: two shouldered-tankards, several double-handled and one-handled cups, one mottled and one dark Bass bowl, a kantharoid cup, a coarse jug and at least one medium-sized jar, together with an impressive narrow collar-necked painted amphora with horizontal handles, and a globular amphoriskos with vertical handles and pierced horizontal lugs on a roped band (Fig. 10). In the eastern part in this section of the HCH, was uncovered a segment of another elaborately paved floor, laid with pebbles of brown-red chert.

Fig. 9. Restored pithos from trench H43 (The Helike Project 2011, drawing by Y. Nakas).

Fig. 10. Cup, Bass bowls, tankards, amphoriskos and painted amphora from the storage room of the Helike Corridor House (photo: S. Katsarou).

The Corridor House, an example of a standardised architectural plan found at a number of EBA settlements, is much discussed, for it is thought to imply centralised administration and a hierarchical social order; this debate is, to a large extent, generated by the large assemblage of sealings found at Lerna (Wiencke Reference Wiencke1989, Reference Wiencke2000; Maran and Kostoula Reference Maran, Kostoula, Galanakis, Wilkinson and Bennet2014). In fact, putting aside their architectural monumentality, most of the other Corridor Houses have yielded a fairly standard set of portable finds and accessories (Shaw Reference Shaw2007), and in fact no solid evidence for large-scale and long-term storage (Pullen Reference Pullen2011b). Consequently, the discovery of the HCH in the heart of the town has a great potential for the exploration of issues, such as surplus management and social stratification in the EBA, in the context of the whole settlement rather than just of the house itself. The history and life of the HCH, as well as its social character, can be better clarified when compared and paralleled with the history and life of the town.

To start with the account of data from the structure itself, the HCH resulted from modifications applied in early EH III to an earlier (late EH II) building of a simpler long rectangular plan, in order to accommodate additional peripheral rooms on the ground floor (including the corridors), and an upper floor that would be accessed by a stairway, thereby achieving increased space and monumental height. Side corridors are, in any case, a frequent and increasingly commonly recurrent feature in various types of EBA buildings, and can be associated with the rapidly increasing need for larger storage areas and more spatial comfort for the residents of the period. The HCH revealed in the early EH III Helike and its type dependency on ‘architectural remnants of the preceding EH period’ is noted in relation to another such corridor building uncovered at early EH III Tiryns (Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 189).

In order to further explore the building choices employed for the construction of the HCH, and with an eye on the social insights of this architecture, The Helike Project performed structural integrity modelling and simulation studies with special focus on the building materials and the overall plan of the House. More specifically, the analysis addressed the technical choices made for the addition of the corridors and the arrangement of staircases inside the stairwells, and the estimation of loads exerted on the side walls from the addition of a second floor. The results have demonstrated (Kormann et al. Reference Kormann, Katsarou, Katsonopoulou and Lockforthcoming; Kormann et al. Reference Kormann, Katsarou, Katsonopoulou, Lock, Campana, Scopigno, Carpentiero and Cirillo2016) the dynamic and technically sophisticated practices observed during the implementation of the project, which implies extensive experience of building techniques and relevant advances (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. 3D model of the Helike Corridor House (M. Kormann 2015).

In particular, a series of claims can be made about the design and choices in its implementation:

-

1. earlier walls were strengthened to make the foundations of the HCH capable of supporting a second floor;

-

2. the doubling of the external walls to accommodate the corridor-stairway on their interior made the long side considerably more rigid than if they were single and the staircase was free-standing inside, thus totally removing the possibility of buckling on the ground floor;

-

3. risk of buckling was averted by adding cross walls at 90° to the long side corridors;

-

4. in addition to just providing access to the second floor, some of the corridors may have accommodated supplementary rooms on the outer part of the ground floor and a more complex entrance, and may possibly have supported one or more upper storey balconies;

-

5. the facade wall which would be most susceptible to buckling was built with increased thickness compared with the other sides; the suitability of the building materials assumed to have been used has been validated by successful structural integrity tests for their loads under normal circumstances.

To sum up, the observations on the basis of the simulations have proved that the designers and builders of the HCH were able to identify the static load risks in the house; they were capable of securing the structural integrity of the building by solving any risk of buckling in the long side wall which would arise from the addition of a second floor through the employment of their technique for building the corridor together with the accommodation of the staircase or balcony as required. Considering the technical innovation in its social dimension, the simulation results have provided a glimpse into the dynamic social world of the town of Helike. The HCH is a monumental house hosting domestic functions on the ground floor including very characteristic household activities such as cooking and dining, as well as large-scale storage of staple foodstuffs, which would fill the shelves with a wide variety of tableware in the same rooms.

The HCH is, however, not the only building in the whole town to house very large jars. Several of the nearby houses contain an equal or even larger number of storage containers standing on floors in rows against their long side walls, as well as smaller jars and amphorae among the other contents of the same rooms. Some of the rooms containing the jars appear to have been intended primarily for storage, although most of them seem to have served various other functions at the same time. The record from Helike suggests serious reconsideration of Pullen's (Reference Pullen2011b) argument for small-scale household consumption and storage or limited centralised control of staple goods in the EH Peloponnese, which is based on the low number and capacity of the pithoi recorded at other sites (i.e. House of Tiles and other buildings at Lerna, Petri at Nemea). In fact, the HCH enables us to explore more refined approaches than the automatic inference that it served a hierarchical role and its function was as the seat of a chief; we can assess the building in association with the overall architecture of the town rather than simply its construction as a monumental achievement and as a large storage place. Without denying its collective and possibly administrative character, we would also like to take a closer and more reflective look at the aspect of private ownership, which seems to be corroborated by the HCH itself, implying that the town was flourishing under a regime which saw collaboration among a number of private entities, whose rise ultimately led to the town's growth and an enhancement of its status. This approach can find further support from the arguments recently put forward for the development of hypaethral spaces in the interior of Corridor Houses, as demonstrated on the basis of the building at Lerna, as a means to promote encounters of a social and political nature, not to say ritual communication between various members or groups in the community rather than for hosting just one person's or a specific kin's residence or seat (Peperaki Reference Peperaki2004, Weiberg Reference Weiberg2007, Pullen Reference Pullen2011b and Reference Pullen, Terrenato and Haggis2011c; Maran and Kostoula Reference Maran, Kostoula, Galanakis, Wilkinson and Bennet2014).

Sophisticated devices

The interiors of the buildings in EH Helike are furnished extensively with features exhibiting an advanced technological level, such as specially made stone platforms inside the rooms to support large storage vessels (H22) or platforms paved with alternating layers of flat stones and large pottery fragments, most probably used as benches (H38, Fig. 7), although we would also suggest an alternative function for this particular feature in H38 as being associated with ritual purposes. Equally noteworthy is another impressive clay structure, 1.75/1.70 m long and 0.55/0.65 m wide and preserved to an average height of 0.65 m, discovered in one of the rooms of the north-western part of trench H65 (Fig. 3) during the 2011 excavation campaign. The structure, of brown-orange colour, with an opening to the west 0.50 m wide and three sides with thick walls in the shape of the Greek letter pi, occupies almost the centre of the room (Fig. 12). The exceptional number of medium and large pithoi found near this feature, and especially on its eastern and northern sides, indicates the possible use of the room for communal storage.

Fig. 12. Clay structure discovered in trench H65 (photo: D. Katsonopoulou).

To better define the character of this unique construction, for which no close parallels are known from excavated sites of the same date, selected samples were taken both from the structure itself and from the surrounding soil to study its consistency and technological features based on petrographic, mineralogical and geochemical analyses. The preliminary results of this work conducted at the Laboratory of Mineral and Rock Research of the Department of Geology, University of Patras, showed a calcareous consistency in the clay mass, with limestone forming a large proportion of its constituents, as well as microfossils and in a lesser degree chert and mudstone, thus suggesting that the raw materials for building the construction were collected from the local area. Although elements in common with those characterising one of the Helike pottery fabrics were observed (group B; Iliopoulos, Xanthopoulou and Tsolis-Katagas Reference Iliopoulos, Xanthopoulou, Tsolis-Katagas and Katsonopoulou2011), the clay feature cannot altogether be compared with the pottery groups. Inclusion of calcite and clayey minerals further indicates either that its firing temperature was kept very low (as was also the case in the firing of the large pithoi from the settlement) or that it had not been fired at all. Although the evidence is not strong, the possibility that the feature may have been used as a container for raw material in the manufacture of pithoid jars cannot be excluded.

OBJECTS INDICATING WEALTH AND STATUS

The Depas Amphikypellon, gold and silver items

One of the most exceptional material assemblages from EH Helike was recovered from the long rectilinear building flanking one of the town streets excavated in trench H22 in 2001, where quite a number of unexpected finds came to light. Restoration (by our conservators at the Helike Conservation Laboratory) of the fragments of a vessel collected from the interior of Room 1 in Building 2 (Fig. 3) enriched our EH Helike pottery collection with a rare vase – an exceptional type of drinking vessel related to particular customs, even associated with ritual drinking, a depas amphikypellon of late EH II date. The almost completely preserved Helike depas cup has a tubular body preserved to a height of 19 cm and with a diameter of 5.2 cm almost throughout its height except for the rim (5.7 cm) and base (3 cm). Two vertical arched handles are attached at two points of the body, the higher under the rim and the lower above the base (Fig. 13). Its outer surface is covered with a lustrous red–brown slip and is decorated with an incised floral ornament placed above the base. The ornamentation consists of small leaves sprouting from a long, thin branch incised vertically on the left front side above the base, near the left handle, and a second thin but shorter branch next to and parallel with it (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 76–7, 80–1 figs 17, 18). The Helike depas is of a markedly different texture from the rest of the Helike assemblage in terms of fabric and surface finish: it is fine-grained, covered with a light but homogeneous slip which has been polished vertically and fired red-brown. In the sections of its fragments, the very light colour of the core can be observed. Its difference from the coarse fabrics and unslipped surfaces, and the black-fired cups, of the Helike assemblage can be attributed to a large extent to its chronological priority in late EH II rather than EH III. Until non-destructive provenance analysis of the item becomes possible, macroscopic observation shows features quite distinct from the local contemporary pottery, supporting a non-local origin.

Fig. 13. The Helike depas amphikypellon cup from trench H22 (photo: D. Katsonopoulou).

The depas cup is a prestigious type of vessel with a broad geographical distribution over the Aegean and western Anatolia (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu, Şahoğlu and Sotirakopoulou2011, Reference Şahoğlu and Lebeau2014), with few examples or imitations on the Greek mainland. More specifically, the closest parallels for the depas from Helike can be found in similar cups from Αyia Irini on Keos (Wilson Reference Wilson1999), Pevkakia (Christmann Reference Christmann1996, pl. XVII:2), Troy (Aruz and Wallenfells Reference Aruz and Wallenfells2003) and Küllüoba in western Anatolia (Efe and Ay-Efe Reference Efe and Ay-Efe2001). In particular, the high raised, arched handles of the Helike cup, with the arc flexed more sharply than usual, find the closest parallel in examples from Keos, Pevkakia and Troy. We should note, however, that the Helike depas has an even sharper arc (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 77). Its discovery changes the distribution map of this unique cup in the Aegean world, extending its dispersal to the western Greek mainland as far as Achaea. In particular, within the region of southern Greece only three other examples are known: from Tiryns (Müller Reference Müller1938, 77), Lerna (Rutter Reference Rutter1995, 86 fig. 6) and Kolonna on Aegina (Walter and Felten Reference Walter and Felten1981, 122 fig. 107); the depas from Helike adds the region of Achaea and the south-western coast of the Gulf of Corinth to the map of trading activities and contacts with various centres in Asia Minor and the eastern and north-eastern Aegean (Rahmstorf Reference Rahmstorf2006).

The depas represents the only example of the ‘Kastri Group/Lefkandi I’ assemblage at the site so far, and stands apart within the context of local ceramic features. The cup, no doubt a prestige object for its owner, is most likely an imported vessel, either a gift offered or an exotic item brought over in distant voyages, in any case an object inscribed with a particular symbolic value for its owner and raising their personal status within the town's society. Its social value becomes even greater, considering that the incised motif above its base may actually represent an ‘ideogram’ (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 80) which would invest the cup with the significance of carrying a communication, in addition to its function as a cup and its prestige as an exotic possession to own and display.

The importance of this outstanding cup from Helike is further strengthened by the identification of the depiction of a similar depas on a clay object discovered in one of the southern rooms of the HCH in trench H43 (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 81 fig. 19). The find, of a grey clay including predominantly dark-brown, radiolarian chert fragments similar to the clay of many pithoi from our site, is preserved in two joining fragments displaying the incised depiction of a depas cup with a tubular body and two arched handles (Fig. 14), closely resembling the form of our actual depas found in Building 2 in trench H22 (Fig. 3), located about 20 m west of H43. The item evidently confirms some kind of link between the private house and the supposedly central HCH, but may even allude to some closer relation between either their residents/owners or the functions of the two buildings. It also underlines the value of the depas as a shared symbol of exotic connotation among different contexts in the town.

Fig. 14. Adjoining clay fragments with incised depiction of a depas cup from trench H43 (photo: D. Katsonopoulou).

The discovery of two other luxurious finds, of a kind extremely rare in EH settlements, in the same building complex of trench H22 where the depas was also found, raises more directly questions about the accessibility of wealth for the residents of the houses, quite apart from objects of exotic origin and prestige status, and offers a stronger argument for the rise of elites. The items, a circular, gold ornament pierced by four perforations symmetrically placed in its centre apparently to be attached to valuable clothing (Fig. 15a ), and a fragment of another ornament in silver (Fig. 15b ), were found inside the apsidal Building 3 (Fig. 5) adjacent and just to the east of the rectilinear Building 2, where the depas cup was discovered (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 81 fig. 20). Items made of precious metal are generally rare in EH sites and come almost exclusively from graves. Their presence in one of the Helike houses is thus of special importance for highlighting the status of the owners in the context of the town, as a matter of wealth, prestige and overseas contacts or travel.

Fig. 15. Gold ornament (a) and silver fragment (b) from Building 3, trench H22 (photo: D. Katsonopoulou).

DRINKING AND STORING

Pottery

The advanced social setting attested in EBA Helike is also echoed in the wide range and number of ceramic containers obtained to meet the functional needs of the houses. In terms of form, they align with the new pottery repertoire on the mainland, which demonstrates a marked shift in EH III from the styles of the preceding phase (Rutter Reference Rutter1995; Pullen Reference Pullen2011a), and, as elsewhere, at Helike their provenance is predominantly local.

Detailed petrographic and provenance analysis conducted by the Laboratory of Mineral and Rock Research of the Department of Geology, University of Patras (Iliopoulos, Xanthopoulou and Tsolis-Katagas Reference Iliopoulos, Xanthopoulou, Tsolis-Katagas and Katsonopoulou2011, 129–32; Katsonopoulou et al. Reference Katsonopoulou, Iliopoulos, Katsarou, Xanthopoulou, Photos-Jones, Bassiakos, Filippaki, Hein, Karatasios, Kilikoglou and Kouloumpi2016) has attested to the use of raw materials procured from the local fluvial and alluvial sources, as testified by their geological characteristics and their predominantly rounded and subrounded grain form: mainly mudstone and radiolarian chert, quartz, calcite, clay-slate and meta-conglomerate rocks were crushed to grits, covering almost the entire size range from fine sand to pebble, in order to temper the local clay material. Two main fabric groups were defined which are compositionally similar and vary in terms of grain size frequency and size of particles. This implies the employment of standardised fabric mixing with regard to the forming of certain shapes and the modification and firing choices applied. It seems that these distinct practices were targeted to manufacture certain categories of containers that were distinct in terms of style and function, possibly also in terms of their significance (Katsarou-Tzeveleki Reference Katsarou-Tzeveleki and Katsonopoulou2011, 89–106).

Pottery from the EH II context is considerably fragmented. It is of fine-grained texture and lighter colours and shows oxidised firing through the core. Main macroscopic groups include dark Urfirnis ware, as well as brown- or red-slipped and orange ware with porous texture and highly eroded surfaces. Shapes include saucers, sauceboats, deep hemispherical bowls and medium-sized jars with inverted, triangular rims or thickened rounded rims on incurving walls (Fig. 16). Wide vertical strap handles on closed bodies, incised horizontal handles, ledges, and ring-bases are the most usual features, comparing with Lerna III (Wiencke Reference Wiencke2000). Several jars carry roped bands manufactured by overlaying discs rather than finger-impressing on the shoulder, finger-impressed rims (Fig. 16e , h , j , l ), or have scored surfaces.

Fig. 16. Selection of EH II vessels (illustrations and photos: S. Katsarou).

In the EH III, the red-brown/dark/black fired polished style (commonly mottled) predominates. It applies mainly to tableware for the serving and consumption of food and drink, which includes the larger number of the containers excavated from the settlement: to these types belong rim- and shoulder-handled tankards, one- or two-handled flat-based cups, and also the typical type of Bass bowl (Fig. 17; also Figs 8, 9 and 10). They also include medium-sized, wide-mouthed and narrow-necked jars (Fig. 18a ), pyxides, amphorae including some with a dark-on-light patterned decoration (Fig. 18c ), cooking pots, deep bowls (Fig. 18b ) and some rare vessels such as the collared and squat globular amphoriskos and the multiply perforated, pedestal-footed lamp (Fig. 18d ; also Figs 8, 9, 10 and 17).

Fig. 17. The depas cup (1) and the range of EH III table, cooking and storage vessels (illustrations: Y. Nakas).

Fig. 18. EH III vessels: (a) amphora, (b) krater, (c) dark-on-light patterned amphora and (d) footed lamp (photos: D. Katsonopoulou and S. Katsarou).

The vessels have in common, in terms of the proportions, range and variance of their minor constituents, the same main composition; some of them show angular inclusions that point to sources other than fluvial. A few, small drinking tankards show very elaborate working of their paste, to produce a fine fabric with the employment of silty fraction. On the other hand, the conspicuous, large, standing pithoi (Fig. 9) fired to a red-brown, constitute a class of their own. The bimodal distribution of their mudstone component is a typical feature along with the frequent use of calcite.

Possibly one or more pottery workshops would have existed in the town, although not yet recovered by excavation, where these local types of pottery were produced and from where they were then distributed. The evidence for the use of wheel-fashioned manufacturing techniques in the ceramic record of EH III Helike is comparable with similar evidence recently recognised in the pottery from contemporary Lerna IV (Choleva Reference Choleva2012), and Ayia Irini (Gorogianni, Abell and Hilditch Reference Gorogianni, Abell and Hilditch2016) and implied for other EBA contexts as well (Knappett Reference Knappett1999). The diagnostic signs include parallel striations and a micro-relief of grooves and ridges, as well as symmetrical wall thickness, which point to the employment of rotative manufacturing practices, mostly for finishing off coil-built vessels among the fine and coarse shapes of Helike tableware. The mastery of the new potting techniques at this period implies increased investment of time and labour. This points to a workshop organisation of production, in other words to the development of potting production to a full-time specialised undertaking driven by economic considerations (Gorogianni, Abell and Hilditch Reference Gorogianni, Abell and Hilditch2016); these would favour the advancement of skills and expertise of the potters to achieve greater productivity in order to meet the increased consumption needs of the town, at the lowest cost in raw materials and time.

From the social side, this specialisation is another indication that the community was organised on the basis of defined groups; the rise of an elite and the concentration of wealth is a demarcation relying on the privileged access to the exotic, while craftsmanship relies on personal skills. Although we may not yet be able to fully understand if there is any connection between the two levels, we may infer that mastery of the new forming technology presupposes fundamental feedback from widely distributed techniques of manufacture and extensive interaction between potters (Choleva Reference Choleva2012), and perhaps also non-local masters.

The large pithoi from Helike, in particular, may provide a better guide in this approach. They consist of the very tall jars set on the floor, which combine the quality of a container with that of a permanent architectural feature indoors, given their large size and their special location inside the house, evidently decided as part of the building plan, in order to provide a special area for the provision of the long-term storage of staples. They are widespread in almost all the houses of the settlement, although their number may vary from one building to another, and depending on whether the room served one or many functions. In total, there were over 15 such jars standing more than 1 m high.

In a recent study (Katsonopoulou et al. Reference Katsonopoulou, Iliopoulos, Katsarou, Xanthopoulou, Photos-Jones, Bassiakos, Filippaki, Hein, Karatasios, Kilikoglou and Kouloumpi2016, 15–16), we have developed the challenging argument that the large pithoi may have been manufactured by a distinct group of specialised artisans who would be capable of handling the demand for extra size. We have also extended this concept to allow for itinerant pithos makers, in the way the case has long been made for itinerant ceramic craftsmen in the Argive plain and Minoan Crete in the same period (Wiencke Reference Wiencke1970, 103; Christakis Reference Christakis, Rutkowski and Nowicki1996; Cummer Reference Cummer and Betancourt2015). The masonry at Helike has revealed the use of a particular stone imported from elsewhere in the Peloponnese; given that, we have proposed a possible interconnection between itinerant potters making big jars and the house builders who would have undertaken some of the building projects in the town.

Returning to the subject of the influence attested from other Aegean cultures on the local pottery of Helike, we would further contend that the sophistication of local craftsmen may have offered an opening for their patrons to project social display and personal prestige. In fact, inside the houses of Helike, the apparently contrasting qualities of practical function and display should not be thought of as mutually exclusive. Here, we may assume that alongside the ceramics physically imported there also existed a trend towards the imitation of non-local products to create social values and construct social strategies inside the town. This Broodbank has expressed as ‘uneven values for non-local goods and superior knowledge that forms an avenue to power’ (Broodbank Reference Broodbank1993, 315). The features imitated may include the elaborated and decorative characteristics marking the pots as well as their practical and usable features. These qualities seem to apply to a number of locally made and prominent vessels from the Helike settlement, including drinking sets of tankards and Bass bowls and the vessels with potter's marks. The Helike tableware (cups, bowls and tankards) of the EH III, exhibiting angular outlines together with dark burnished surfaces, shares the strong metallic fashion which is one of the typical aesthetic features introduced in the period. At other sites, the stylistic trend has been discussed as indirect evidence of the widespread influence from the production and use of metallic tools, containers and accessories (Rutter Reference Rutter1983), whose imitation in clay may have increased the prestige and display value of pottery containers. Even more, the metallic appearance of clay cups and containers demonstrates the link between drinking and serving habits with the distribution of metals and, possibly, suggests the orientalising origin of both (Rutter Reference Rutter2008). This link, also evident in EH III Helike, further supports the town's predilection for the drinking culture as a connotation of prestige and display.

On an initial level, the drinking sets, which show a marked increase in Helike by the earliest EH III, follow the noticeable growth trend attested elsewhere in the Aegean (Wilson Reference Wilson1999; Day and Wilson Reference Day, Wilson, Halstead and Barrett2004, 48; Rutter Reference Rutter2008, Reference Rutter, Maran and Stockhammer2012). More specifically, beyond their local origin of manufacture, the pots show very close stylistic similarities to the material revealed in the contemporaneous settlement of Aegina-Kolonna (phases D and E) in particular (Gauss and Smetana Reference Gauss, Smetana and Bietak2003; Reference Gauss, Smetana, Bietak and Czerny2007, 457 fig. 4). This observation applies especially to Bass bowls with rounded or up-swung handles and a slightly everted rim, dark and mottled polished surfaces, occasionally pattern-painted decoration, and unpainted brown/dark burnished surfaces for most medium-sized deep bowls and jars. Imports from Corinthia and the Argolid have been identified in Kolonna phase E (Gauss and Smetana Reference Gauss, Smetana, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008, 326–9); therefore, although at first sight the distance between the Saronic Gulf and the north-west region of the Peloponnese might seem too great, coastal interaction along the Gulf of Corinth need not be out of the question as a channel for stylistic influence. It should be noted, however, that no pot of Aeginetan provenance has been identified within the material discovered in Helike.

In a wider context that goes beyond the cultural similarities between the two sites, certain fashionable ceramic attributes found at Helike, such as the black lustrous surfaces, the mottled effect, the increase in angular profiles, particularly with regard to the tankards with their long conical necks and flat bases, and more generally the cups and serving vessels, show an international aura. Their occurrence integrates the EH town into a cosmopolitan sphere, thriving throughout the Aegean and Crete, distinguishable through vases with a metallic appearance imitating metal prototypes (Day and Wilson Reference Day, Wilson, Halstead and Barrett2004, 53; Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu and Lebeau2014, 299–304). The prevalence of these trends at Helike, situated in the western region of the mainland, is strikingly similar to those found in its counterparts elsewhere in the Aegean, indicating that the local pottery craftsmen were trained in certain standardised techniques that were necessary to follow styles in fashion over a wide area. Alongside the drinking sets, the depas cup is itself one of the distinct vessels imitating metal prototypes, to be interpreted as a symbolic good distributed along the Anatolian trade network in metals (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu and Lebeau2014, 292).

In an attempt to acquire a thorough insight into the social background to this extensive material transformation towards a culture of drinking, scholars have imputed increased inter-household competition in a broader Aegean context in the Cycladic (EC IIb), Minoan (EM IIb) and Anatolian contexts (EB2). Day and Wilson (Reference Day, Wilson, Halstead and Barrett2004, 58–9) have argued for a possible increase in hospitality and formal convivial ceremonies, where the individualised sizes of drinking vessels – which are standardised to a given size and made in sets with serving vessels – operate in favour of individual performance. In EH III Helike, the abundant drinking cups found in the houses, usually together with serving vessels, and their standardised size attest to participation of the town in this symposiac culture. This arena of increased personal and family status, where the roles of host and guest might be played to distinguish a position of authority, should be considered as the social context also shared by the EH III town of Helike.

Furthermore, Helike has produced a good number of sherds with ‘potter's marks’; most belong to thick-walled vessels, presumably jars, and one is, very unequivocally, incised on the neck of a large, restored storage pithos from the Corridor House (Fig. 19a ). They feature clearly recognisable signs from the known repertoire such as parallel chevrons and stem-like symbols, as well as plain short lines. On a restorable vase from the Corridor House, a marking in the form of a thunderbolt was found (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsonopoulou2011, 75 fig. 13) (Fig. 19b ), comparable to a similar one from the site of Lithares (Tzavella-Evjen Reference Tzavella-Evjen1984, 167 fig. Zb). ‘Potter's marks’ are particularly common in the Cyclades – especially on Keos, Melos and Thera – and Aegina (Bikaki Reference Bikaki1984; Shepard-Bailey Reference Shepard-Bailey1996; Lindblom Reference Lindblom2001), in fact more common and earlier, by several centuries in the third millennium bc, than those found on the Greek mainland. From a morphological perspective, these pre-firing incised signs are interpreted as a kind of notification that is inscribed on the containers in the form of symbols deriving from a corpus of a widely ‘understandable’ proto-script. They have been thought to convey messages related to the production process in terms of the vase's volume, origin, final location and similar practical information. Recently, in the context of Late Bronze Age Anatolia, such marks have been seen as indications to record the individual effort of the manufacturer within a context of centrally managed pottery production (Glatz Reference Glatz2012). Their frequent presence on the pottery found at Helike further corroborates possible links with the Aegean. On the other hand, given the development of structured social identities, including that of the specialised potter producing within a specialised workshop, we may consider the possibility that they indicate the level of personal achievement as another expression of elitism and social recognition as a skilful potter. This is a useful angle to look at vessel production, actually an angle that strengthens the arguments for a demarcation of personal identities in EH III society, whether on the basis of wealth, as for the elites, or labour- and skill-dependent qualities as for the potters.

Fig. 19. ‘Potter's marks’ (a) on the neck of a large restored storage pithos and (b) on a restorable vase from the Corridor House area (photos: D. Katsonopoulou and M. Kormann).

Tools

Another interesting category of find from the buildings of EH Helike is tools. Excavations showed that the houses were equipped with an array of stone implements including spherical pounders/rubbers, made primarily from grey and red limestone, and trapezoidal or triangular celts fashioned from hard stone, and also pointed bone tools hardened through firing to be used for piercing, as well as a significant chipped-stone assemblage. The preliminary analysis of these artefacts suggests that tool manufacture was local, with significant parallels to the lithic industry at Lerna in terms of tool types and craft skills. The range of tools met the needs of agricultural and woodworking activities and provided weapons for hunting and warfare (Thompson Reference Thompson and Katsonopoulou2011). Although the industry at Helike seems to have relied primarily on local sources of material, we note the presence of tools and denticulates of Melian obsidian (Thompson Reference Thompson and Katsonopoulou2011, 149–50, 150 fig. 5). This imported component of the lithic assemblage need not simply point to adventurous seafarers originating from Helike and developing direct trading contacts with the Cyclades. It may possibly be better understood as positive evidence for the networking contacts of the town with the source from which the specific material and/or its finished products would be supplied. Itinerant lithic specialists have even been proposed for the distribution of this material (Karabatsoli Reference Karabatsoli1997; Pullen Reference Pullen2011a). Actually, the choice of a Cycladic raw material, however it was procured, may rather forcefully imply a link to the exotic and cosmopolitan Aegean world (Carter Reference Carter1999, Reference Carter2007), and present another part of the scene of the same play of prestige politics at home.

CONCLUSIONS

Following EH II, Helike in the early phase of EH III emerges as a conspicuous administrative, economic and trading centre on the south-western coast of the Gulf of Corinth, which had established advanced contacts with the East and was engaged in the long-distance networks of the time. In the third millennium bc, travel by sea extended to unprecedented long-range destinations, which associated the Levantine coast with south Italy and Mediterranean regions even further to the west (Broodbank Reference Broodbank2013a, 117), especially from the time of the orientalising cultures of ‘Kastri Group/Lefkandi I’ onwards (Rutter Reference Rutter1979; Manning Reference Manning1995; Pullen Reference Pullen2013; Renfrew Reference Renfrew1972). The technical advances in navigational skills and vehicles that would have enabled the long-range interconnections have been conjectured to lie behind these innovations and the appearance of the new social dynamics (Broodbank Reference Broodbank2013b). In the light of the fresh concrete evidence provided by the excavated data from Helike, and not just by mere reasonable conjecture on the basis of the geographical route only, this seafaring expansion can now be transferred even further west to include the western Greek mainland.

In an overall comparative assessment, at site level, the transformation of EH Helike as a whole to a proto-urban centre in the EH III through the implementation of a gridded town-plan, fortification, diversified monumental architecture as evidenced by the Corridor House, and specialised spatial functions to accommodate long-term storage (also Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 190), falls within the pattern of towns emerging by that time, and regarded as a precedent to the states and chiefdoms of the second millennium bc (Cherry Reference Cherry1984; Pullen Reference Pullen2011b, Reference Pullen, Terrenato and Haggis2011c). This new social form became possible through the employment of these innovations and their transformative potential (Maran and Kostoula Reference Maran, Kostoula, Galanakis, Wilkinson and Bennet2014). The house is the basic component of this new form, not simply as a physical locus, but as a stage where institutionalised and codified behaviours emerge as building blocks of the society (Kristiansen and Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005). Easy suppositions of a fixed hierarchy and the development of clear social ranking seem to need cautious reading here: the overall picture from architecture and distribution of material wealth raises instead the possibility for flexibility in power relations shared in the form of federations, coalitions and other structured relations that are not exclusively hierarchical (Kristiansen and Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005). The phenomenon has also been described for Protopalatial Crete, as a swing from short-term, household, storage to centralised storage and redistribution strategies managed through the authority of elites and their associates, who enjoyed access to luxury items and exotic valuables and later developed into the palatial dependants (Christakis Reference Christakis2011).

The institutional complexity witnessed at Helike constitutes the first ostensible testimony that the north-western Peloponnese also shared the formative background that generated the succeeding political entities in the Greek mainland. Little evidence on the EH III, limited principally to pottery, has come from a few other places in Achaea, including Teichos Dymaion and a very late EH III phase in Aigeira (Forsén Reference Forsén1992; Alram-Stern Reference Alram-Stern, Alram-Stern and Deger-Jalkotzy2006), and nearby Aigion (Papazoglou-Manioudaki Reference Papazoglou-Manioudaki1984); however, clear EH III architecture is almost exclusively limited to the Helike remains uncovered so far (also Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 188–90). Within this phenomenon of new power dynamics and their long-term consequences, the architectural innovations attested at Helike at the site level as well as at a house level should rather be regarded as accompanying, or in fact determined by, the emergence of centralised institutions in the town that regulated the management of the settlement, and perhaps also the production and redistribution of stored wealth, but with, at the same time, promotion of an emerging private ownership and household independence.

The shift to organised town planning witnessed at Helike between the end of EH II and early EH III is for that period an unusual phenomenon on the Greek mainland (see also Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 190). The general rule in EH III is actually for a decreasing size in settlements and their marked decline (Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 91 and 103) throughout the mainland; the same can be said about the EH II settlement attested in Aigion (Papazoglou-Manioudaki Reference Papazoglou-Manioudaki1984) and also at Derveni in neighbouring Corinthia, about 35 km east of Helike (Sarri Reference Sarri and Katsonopoulou2011). Outside Achaea, sites in Boeotia, Euboea, Attica, Phocis and the north-eastern Peloponnese (Weiberg and Finné Reference Weiberg and Finné2013) bear witness to a disorganised way of building houses and scarcity of building remains (Pullen Reference Pullen2011a), supporting the ‘gap’ theory long discussed by Rutter (Reference Rutter2013). Only a few mainland settlements are comparable with Helike after the chronological shift, Aegina-Kolonna being the most conspicuous (if considered as a mainland site) or at least the closest, on account of its planned layout, houses grouped into insulae that are separated by streets, fortification walls, apsidal house plan, and even a paved court, as well as metalworking installations. Aegina-Kolonna also parallels Helike in terms of its implications for social change, in terms of the emergence of elites and a major workforce administered through a management hierarchy. The assemblages of storage and pouring vessels likewise attest to distinct socio-economic distribution, and even ceremonial functions. Moreover, the metalworking activities and the jewellery hoard consisting of gold, silver, carnelian and crystal objects imply significant trade contacts between Aegina-Kolonna and the Cyclades and the Near East (Reinholdt Reference Reinholdt2008; Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 93). The other mainland sites of the period that deviate from the rule of decline are Pevkakia in Thessaly (Christmann Reference Christmann1996) and in a more modest way Tiryns in the Argolid (see discussion by Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 146), while nearby Lerna was disintegrating (Weiberg and Lindblom Reference Weiberg and Lindblom2014).

Thus any parallels for Helike, in terms of the town's extent and prosperity, would lie on the eastern coast of the Greek mainland and beyond. Further to the east, this profile of town arrangement links Helike with sites as far as Poliochni, Troy, and Liman Tepe in the Izmir region (Şahoğlu Reference Şahoğlu2008), which also features the typical attributes of architectural planning including a central building of the Corridor House type, together with rich contents. More specifically, in terms of fortification, which is probably evidenced at Helike, this feature is absent from other Greek mainland settlements at the time, while it is typical of the Aegean from the floruit of the late EH II citadels at Palamari on Skyros, Panormos on Naxos, Kastri on Syros, and Markiani on Amorgos. Further south, the accelerated political developments in the Prepalatial sites of Crete (Brogan Reference Brogan2013) paint a picture very different from the decline in EH contexts, while the east Mediterranean at the time is on the rise (Wiener Reference Wiener2013).

On a material culture level, the great variety of associations with places far beyond Achaea are evidenced at Helike either through the physical influx of imported items (depas, gold and silver accessories, Melian obsidian) or as the imitation of/influence from eastern exotic styles (tankards, ‘metallic’ ware) and symbols (‘potter's marks’). The value of the imported items need not depend on their intrinsic high-quality status alone, but also on the added value arising from their remote provenance and the associations surrounding their procurement. We may infer that the developed social organisational regime that would have administered the resources of the town integrated the non-local commodities into the local resources by activating various relations of dominance or dependency inside the town (Broodbank Reference Broodbank1993, 315).

In this context, we may think that the interplay between the local and the exotic would have been quite powerful between the members of a family, household or house or at an individual level at Helike. Houses of the time can be seen as the cradle for emerging institutions, which acquired their status precisely through long-established heritage and longevity. The various imports or foreign gifts and valuables, once introduced into the context of Helike, are translated into the local dialectics of power, which means that they are signified as precious items of personal wealth, status and ritual significance, for display in the social context of the town. This meaning acquired at home may be linked with very particular idioms and narratives for each house, but simultaneously it seems to stand for some structured symbolic connotation which is comprehensible across all social components of the town. The recurring appearance of these symbolic expressions is the backbone upon which these institutions develop and interact through political alliances or competition.

Aside from the precious furnishings, the sense of location is another key factor in this complicated system of symbolic values which are produced and reproduced: the reshaping and widening of older buildings on the same site not only signifies the broad shift in social relations, but also continues as an emphatic statement of their attachment to the very land. With special reference to the silver and gold items from Helike, apparently very particular and unusual personal accessories that were probably meant to serve as ornaments for clothes, they would prompt links with certain sites either in the Aegean or in the Ionian Sea and the Balkan area, where these precious raw materials could be obtained. The limited excavation at Helike so far has not revealed any metalworking installations of the sort known from Aegina-Kolonna, Tsoungiza and Pevkakia, and a few other mainland sites. The imports of gold and silver to this Achaean centre, however, suggest a link with distant areas, if we consider the evidence from provenance analysis conducted at other sites. Aegina-Kolonna had established connections with Attica for the procurement of raw materials; analyses have shown that Thorikos, in particular, should be considered the main source for silver, as well as lead and copper, as its products reached as far as Tsoungiza, Lerna and Nichoria in EH III (Wiersma Reference Wiersma2014, 101). This spread may actually explain why this site developed outstanding elite EBA graves, possibly as a result of exploitation of the mines (Papadimitriou Reference Papadimitriou2010). Lerna in the Argolid testifies to bronze and copper from Kythnos and Lavrion, but also from Cyprus (Kayafa, Stos-Gale and Gale Reference Kayafa, Stos-Gale, Gale and Pare2000). In terms of gold, however, the possible origins may include unexpected locations beyond the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean: for example, the gold items found in the EBA tombs of Levkas have raised the theory of a north–south route for gold from the Balkan area through the Ionian islands (Tomas Reference Tomas, Parkinson and Galaty2009, Reference Tomas, Laffineur and Nosch2011). Whatever the source is, as Kristiansen and Larsson (Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005) note with reference to metals, ‘communities of the time became dependent upon each other by maintaining open lines of long distance exchange in order to secure the distribution of metal from the few dominant source areas’. These networks are not physical and neutral; they constituted lines of exchange, information and cultural links between distinct local and regional traditions for millennia.

The same significance seems to have applied to maritime networks, to judge from the trade in Melian obsidian, another exotic commodity given the context of local flint knapping attested at Helike. Obsidian networks had certainly operated for millennia already (Perlès Reference Perlès1990; Torrence Reference Torrence1986) and probably the circulation of obsidian was still handled by the same long-established network. In this context, its limited occurrence at Helike so far may be due to the limited excavation of the site, and should not be taken to imply that the town was a backwater for the production and use of these ordinary tools. On the other hand, its limited presence could also signify the capability for certain households in the town to access another exotic import, sought for its functional qualities and easy availability (Carter Reference Carter1999). Distant origin, together with a material's peculiar qualities, are again here interpreted in terms of a cosmological perception of crossing boundaries between the town and the distant other, a perception which is far more powerful than any physical quality and availability of the chipped-stone artefact or the raw material. More than the material, the high technical requirements for the manufacture of the chipped-stone tools would have endowed them with connotations of power and would have made them another critical component in the service of the elite and the prestige sphere (Parkinson Reference Parkinson and Pullen2010).

This outward-facing social behaviour in EBA Helike, as viewed through its maritime connections, especially with the East, did not, at the same time, constrain this coastal centre on the Gulf of Corinth from being engaged with extensive contacts with the mainland and the interior of the Peloponnese via active land routes, for the circulation of people and artefacts. In terms of movement by land, we would emphasise the mobility of specialised artisans, in particular potters and builders, whose craftsmanship and skill, besides marking their personal identity, also defined their particular social role. It is, then, possible that expertise in crafts may have become associated with the rising elites and their personal identities, and thus also contributed to the growth of the new institutions at Helike. Specialised craft production in particular, in terms of building construction, pottery manufacture or chipped-stone production, has for long been proposed as the mobilising component for the rising social entities in the EBA, however they might be labelled: chiefdoms, institutions or early states (Parkinson Reference Parkinson and Pullen2010; Parkinson and Pullen Reference Parkinson, Pullen, Nakassis, Gulizio and James2014). This context of crafts which were socially highly valued is later evoked in the Homeric epics, where the elites are presented with the skills of master artisans themselves, as well as with the aura of advanced knowledge gained from distant travels.

The transportation of the artefacts attested at Helike indicates a constant flow of people, traders, intermediaries and itinerant craftsmen who moved along the established land and sea routes to and from the coastal town of Helike, to bring and also to obtain. Mobility as a key link for the enhancement of individual prestige and the rise of ranked societies or early chiefdoms (Maran Reference Maran1998; Nilsson Reference Nilsson2004; Pullen Reference Pullen and Shelmerdine2008) is a theme as old and as much of a landmark as Renfrew's Emergence (Renfrew Reference Renfrew1972; Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw2004; Kristiansen and Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005). Putting to one side the older theories of colonisation and movement, interaction within the ‘international spirit’ spread mainly over the Aegean and the Greek mainland; it marks the routes over which knowledge and fashion were widely transmitted, and these within the new domain would acquire a local ‘meaning’ once absorbed by the value systems of that particular settlement or region. Up to now the western mainland has been given little attention, and the account of western Greece has been limited mainly to the Ionian islands, and in terms of individual finds since there was no report of settlement centres.

Interaction in the advanced EBA has focused on certain morphological features: the apsidal house plan thought to be of northern derivation (Forsén Reference Forsén1992); herringbone masonry seen as an Aegean influence, given its frequency throughout the area of Troy, Thermi, Aghios Kosmas, Raphina, Lerna, Tiryns, Pevkakia (Cosmopoulos Reference Cosmopoulos, Laffineur and Basch1991, 156), both features represented in Helike. More particularly, Rutter has argued for increased mobility upon evidence for the increased imitation of basketry motifs on pattern-decorated pottery, in the form of fully covered or half-woven containers (Rutter Reference Rutter, French and Wardle1988, 85–6; Rambach Reference Rambach2000; Nakou Reference Nakou and Serghidou2007). Maran has also argued for increased mobility on account of incised Cetina wares originating from the Adriatic and found at Olympia (Maran Reference Maran, Galanaki, Tomas, Galanakis and Laffineur2007; Rambach Reference Rambach2010). The most striking material evidence for a widely shared culture lies in the adoption of the fashion for convivial gatherings and feasting. Already attested as an explosion of pottery features (serving and drinking ware) by EH II (Pullen Reference Pullen and Shelmerdine2008; Rutter Reference Rutter2008, Reference Rutter, Maran and Stockhammer2012) and the stage of ‘Kastri Group/Lefkandi I’ phase which was distributed over much of the Aegean, this fashion for house-based ritual performances plays an important role in the rise of interpersonal partnerships and competition which assimilated, reinforced and overlapped with all the other elements of value: long-distance connections, openness across personal and socially demarcated boundaries, prestige and status display in a house and town context, skilled craftsmanship and the rise of institutionalisation through the adoption of symbolism. Cups for drinking acquired a vital personal, social and ritual role which culminated in the palatial rituals within less than a millennium.

In this ‘international’ context, Helike, located in the western part of Greece, confirms that long-distance interaction does also include the region around the Gulf of Corinth to the west. The geopolitical picture of the region, later known as historic Achaea, as an area marginal to the core of the EBA needs to be thoroughly rethought on account of the nexus of evidence for an ordered settlement and artefact wealth from Helike. This is also true for the Late Bronze Age (LBA), when the region of Achaea, called Aigialeia or Aigialos before the arrival of the Achaeans at the end of the Mycenaean civilisation (Katsonopoulou Reference Katsonopoulou, Betancourt, Karageorghis, Laffineur and Niemeier1999, 411–12), was traditionally regarded by scholars as one of the regions peripheral to Mycenaean civilisation, one which did not give rise to full palatial states. However, the flourishing non-palatial culture of these regions has recently inspired a reassessment of the ‘palace dependence model’, and, most importantly, attributed to this area a political background which was constructed upon modes of political power dispersed to local elites and less centralised orders (Arena Reference Arena2015). So far, this general approach to LBA Achaea may be used as a projection of an older historical political background in the region, which may call for a reconsideration of the arguments about the unclear nature of the EH polities, their limited long-distance contacts and their circumscribed ability to manipulate the political economy (Pullen Reference Pullen2011b).

Finally, the full account from EH III Helike, integrating architecture and material culture, not only corrects the balance of research that has so far relied on scanty material remains, but in fact enables a good insight into the social context of this early urban centre, situated near the exit of the sea route to the West via the Gulf of Corinth. To conclude, the emerging picture of the social context at EH Helike, in the second half of the 3rd millennium bc, is one of rising elites who developed institutional means to exercise their power based on an ostentatious display of their cosmopolitanism, but at the same time also favouring some kind of collaboration or interdependence in the administration of the town.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the INSTAP and the Municipalities of Diakopton and Aigion for their contributions to the excavations of The Helike Project. Constructive reviews by Bill Cavanagh and two anonymous referees are much appreciated. Stella Katsarou would like to specially thank the Margo Tytus Program for a fellowship at the Classics Department and Library of the University of Cincinnati in 2016, where she has conducted the final part of this research. The Helike Project conservators Konstantinos Kioussis, Maria Siatra, Demetra Balafa and Aimilia Nifora are thanked for their excellent work on conservation of the Helike Early Helladic pottery. Finally, thanks also go to the EH excavation trench supervisors, archaeologists Melanie Fillios, Maria Stefanopoulou and Dimitris Palaiologos.