INTRODUCTION

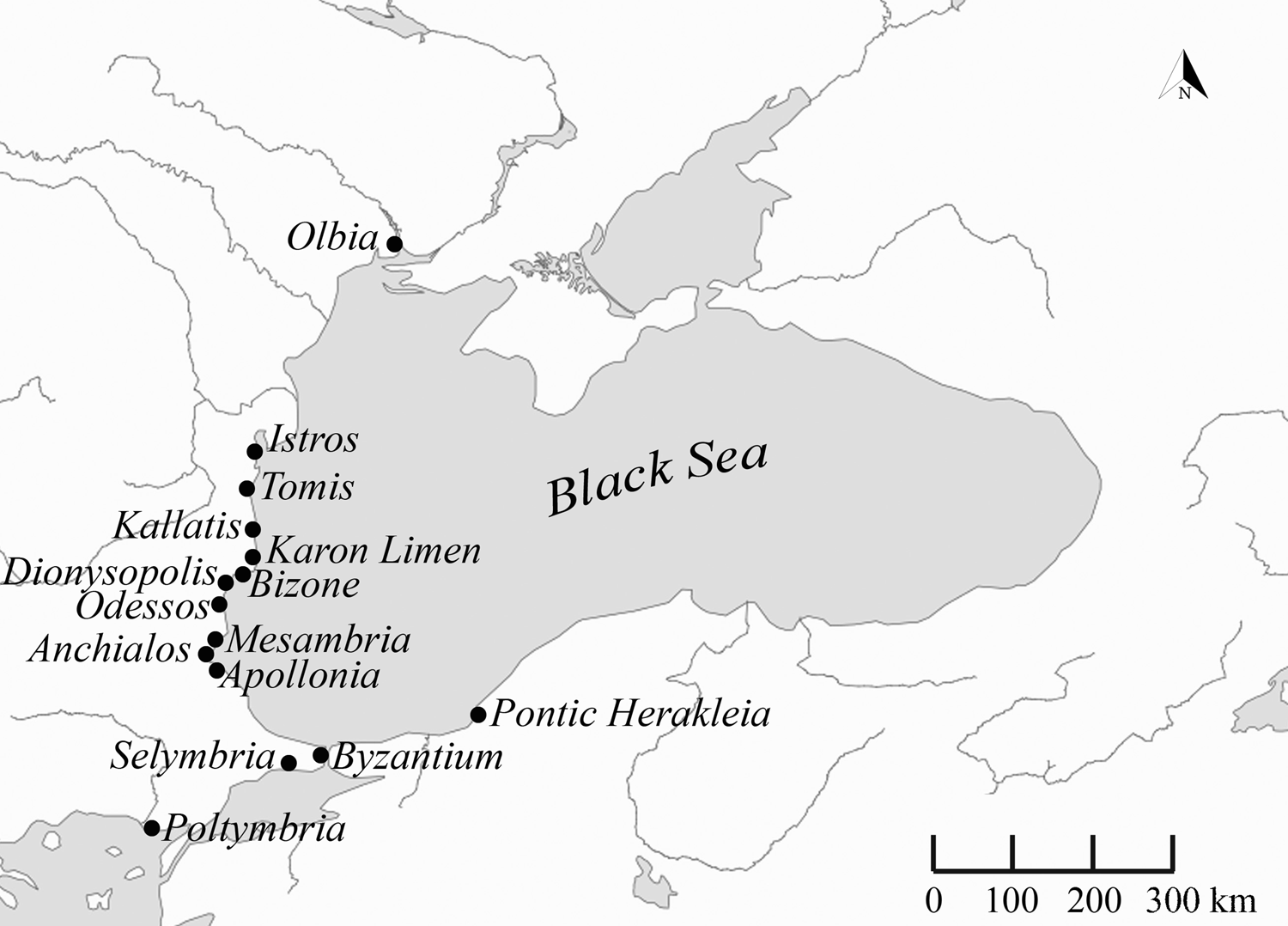

The conventional image of Greek colonisation sees a group of settlers from one polis, led by an aristocratic oikistes, undertaking a dangerous overseas voyage and founding an apoikia either with the consent of the local population or through the use of force. Whether this was the case in the Western Pontus, the area from Apollonia in the south to Istros in the north, remains unknown due to a lack of adequate sources (Fig. 1). This area is conspicuously absent from the interests of early Greek historians, while local inscriptions never record the word οἰκιστής.Footnote 1 The process of setting up the Western Pontic cities has been reconstructed on the basis of archaeological evidence and, in most cases, on much later literary accounts, from Strabo to Ps.-Scymnus and the anonymous Periplus Ponti Euxini, with passing remarks from Herodotus, Aristotle, Memnon, Ovid, Pliny, Aelian, Eustathios, Eusebius and the late antique and Byzantine lexica (Etymologicum Magnum, Stephanus of Byzantium) (for references, see Nawotka Reference Nawotka1997, 16–27; Musielak Reference Musielak2003, 13–24). The colonial age of the western coast of the Black Sea has been dealt with profusely by many modern historians, and this paper does not aim to add anything further.Footnote 2 In the Western Pontus, perhaps more than anywhere else, interest in the founders of local Greek cities and the etymology of their names is rarely attested before the Imperial period, with most evidence dating to the Antonine and Severan age. This paper will review this evidence, trying to establish whether anything in it reflects the authentic colonial tradition, what patterns of foundation stories are detectable, what local strategies were used in promoting foundation stories, and whether we can say anything about the role they played among the elites of the Western Pontic cities. I shall begin with the ‘second foundation’, a phenomenon of the early Imperial age which demonstrates how important the issue of foundation/refoundation was to local elites hundreds of years after the Western Pontic cities were established for the first time. There follows a section concerned with the foundation stories of Kallatis, Dionysopolis, Anchialos and Apollonia, all being of a quite conventional nature, relating the names and foundation stories to gods and major heroes of Greek mythology. The next two sections deal with the well-attested cases of the purported founders of Tomis and Mesambria. The evidence for them comes from different periods, and the stories of the mythological founders of these two cities vary in type. They will be juxtaposed since both were deeply anchored in the self-perception of local elites, although reaching a different level of official recognition. An attempt will be made to trace the development of the foundation myth of Mesambria over much of the Hellenistic age, using a newly published coin and reassessing the existing epigraphic and literary evidence. The last section sums up the discussion, trying to show what patterns of story-telling are discernible in the Western Pontus and what local strategies were employed.

Fig. 1. The Western Pontic cities. Map by Joanna Porucznik.

SECOND FOUNDATION

A phenomenon that could occur after the original foundation of a city is the ‘second foundation’, known from two inscriptions from Istros which mention δευτέρα κτίσις (‘second foundation’)Footnote 3 and one from Kallatis which names a certain Ariston, the ‘second founder of the city': δεύτερος κτίστας τᾶς πόλιος.Footnote 4 The ‘second foundation’ was a historical event, surely preceding the earliest of these inscriptions, ISM III 44 of 12–15 ce, by not much more than one generation, as the honorand is the son of the second ktistes of Kallatis. Although both οἰκίζω/οἰκιστής and κτίζω/κτίστης (‘to found/founder’) may refer to the setting up of a city, in the Hellenistic and the Roman ages, the second term was used more often in the sense of building or re-building a city rather than founding one (Leschhorn Reference Leschhorn1984, 3–5; McEwan Reference McEwan1988; Follet Reference Follet and Létoublon1992). Bearing in mind the calamitous destruction inflicted in the mid-first century bce on Greek cities ranging from Apollonia to Olbia by Burebista, the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82 bce to 44 bce, and the ensuing shortage of population,Footnote 5 the rebuilding of them in the following century is best qualified as their ‘second foundation’ (Pippidi Reference Pippidi1968; Nawotka Reference Nawotka1997, 50; Reference Nawotka2000, 33–4; Musielak Reference Musielak2003, 95–6; Avram Reference Avram, Grammenos and Petropoulos2003, 318). If this is so, an early third-century ce inscription from Olbia, which refers to the ancestors of an euergetes named Kallisthenes, son of Kallisthenes, as the person ‘whose ancestors were distinguished, known to the Emperors and founders of the city’ (προγόνων ἐπισήμων τε καὶ σεβαστογνώστων̣ καὶ κτισάντων τὴν πόλιν), may also refer to the second foundation of this city (IPE I2 42). It took place, it seems, about a generation after Burebista's invasion, and its date may have symbolically coincided with the activities of P. Vinicius, the legate of Augustus in Thrace (Ivantchik Reference Ivantchik2017, 199–201). To the category of ktistes, as a builder/rebuilder of a city, belongs an inscription from Odessos dated to the age of Tiberius which reads: ὑπὲρ τῆς Αὐτοκράτορος / Τιβερίου Καίσαρος θ̣εοῦ / Σεβαστοῦ υἱοῦ τύχης / κτ<ί>στου τοῦ/ καινοῦ περιβό<λ>ου (ʻto the good luck of the divine Emperor Tiberios Klaudios, the founder of the new city walls'; IGB I2 57). It records the restoration in Odessos of a section of the city walls by a local benefactor named Apollonios. The restoration was conducted after regular civic life was re-established in c. 45/44 bce after the destruction inflicted by Burebista.Footnote 6 Apollonios is known from another inscription which contains a list of eponymous priests that reads μετὰ τὴν κάθοδον (ʻafter the return'). In this inscription, which commemorates the restoration of the city walls, the honour of being the (second) ktistes went, however, to the Emperor.

FOUNDATION STORIES AND ETYMOLOGY OF THE NAMES OF KALLATIS, DIONYSOPOLIS, ANCHIALOS AND APOLLONIA

The ‘second foundation’ apart, there is evidence referring to the names and original founders of the Western Pontic cities. An attempt at explaining the etymology of the name Kallatis is recorded, after an unknown source, by Stephanus of Byzantium: Κάλλατις, πολίχνιον ἐν τῇ παραλίᾳ τοῦ Πόντου, Στράβων ἑβδόμῃ. ὡς κάλαθος εὑρέθη ἐοικὼς τοῖς θεσμοφοριακοῖς (ʻKallatis, small town on the coast of the Black Sea. Strabo in book VII. [Named so] because a basket was found [there] similar to those used on Thesmophria').Footnote 7 Explaining that the name Kallatis, which in fact was never spelled with a θ, as derived from kalathos, a sacred basket paraded around on Thesmophoria, is a Greek pseudo-etymology applied to the name which is certainly non-Greek, perhaps Thracian or Lykian.Footnote 8 Six series of coins from Kallatis bear the image of Herakles inscribed as κτίστης.Footnote 9 Kallatis was a Doric city, so the association with Herakles, whose cult is well attested in this city, is not unexpected (M. Dana Reference Dana, Cojocaru, Coşkun and Dana2014, 136–7; Radu Reference Radu2018, 13–15). On top of that, Herakles was the divine founder of Pontic Herakleia, the metropolis of Kallatis, noted for close ties with its Pontic colonies.Footnote 10 One may say, therefore, that Kallatis took over the Herakleote foundation story. Herakles was the most popular mythological founder of Greek cities from Libya to India;Footnote 11 among mortals he was rivaled only by his descendant Alexander the Great, who was credited with founding 70 cities.Footnote 12 Since Herakles appears as ktistes on coins from Kallatis, he may be classified as the official founder of the city.

A third-century ce marble plaque with the Thracian Horseman in relief bears the inscription Ἥρωι κτίστῃ (‘to the founder hero’; ISM III 93). This is the only known example of the Thracian Horseman being addressed as ktistes,Footnote 13 yet it is not the only attestation of the Horseman as a founder, since in Selymbria he was commemorated as archegetes (Leschhorn Reference Leschhorn1984, 373, cat. no. 90). Excluding the very unlikely identification of the Horseman with Herakles, it may attest a parallel tradition attributing the founding of Kallatis to the Thracian Horseman, or the word ktistes may simply be an honorific epithet afforded to the Horseman, without any reference to his role as the actual founder of the city.

The southern neighbour of Kallatis, Dionysopolis, bears a theophoric name whose obvious meaning is explained in a mid-first-century bce decree praising a local benefactor for taking up the onerous duty of priest of Dionysos: τοῦ τε ἐπωνύ̣[μου τῆς πόλεως Διον]ύσου οὐκ ἔχοντος ἱερῆ (ʻwhen Dionysos, after whom the city is named, did not have a priest').Footnote 14 It is no surprise, therefore, that Dionysos was also celebrated as the founder of the city, as we learn from an early-third-century ce titulus honorarius for his priest: ἱερέα τοῦ κτί<σ>το<υ τῆς πόλ>ε[ως] θεοῦ Διονύ<σ>ο<υ> (ʻfor the priest of the god Dionysos, the founder of the city').Footnote 15 The etymology of the name Dionysopolis is first attested in the anonymous Periegesis ad Nicomedem regem, also known as Ps.-Scymnus, and dated to c. 135 bce. The passage in Ps.-Scymnus tells the story of how the city was once named Krounoi, but was renamed as Dionysopolis after a statue (ἄγαλμα) of Dionysos washed up on its shore.Footnote 16

Anchialos, a small town to the south of Mesambria, coined briefly but profusely (284 series) in the first half of the third century ce; one of its coins has a portrait of a young man and is inscribed ΑΝΧΙΑΛΟΣ.Footnote 17 Since the coin bears the identification of the city (Ἀνχιαλέων) on its reverse, the image on its obverse belongs to the eponymous hero Anchialos, almost certainly as his mythological ktistes.Footnote 18 Two more coins bear the same inscription but with a bust of Serapis (Münzer and Strack Reference Münzer and Strack1912, 408–9). Because these coins are the only attestation of Anchialos, we cannot say with certainty how this eponymous hero sprang to life. The Iliad and the Odyssey mention three characters with the name Anchialos: Anchialos a Greek warrior killed by Hektor at Troy; Anchialos father of Mentes impersonated by Athena; and Anchialos a Phaecian.Footnote 19 The name of Anchialos as a Homeric hero is spelled Ἀγχιαλός, not like ΑΝΧΙΑΛΟΣ on the coins. But the name of the city was also spelled with -γ- in stone inscriptions (IGB I2 369, 369bis, 378, 388bis; IGB V 5134; IByzantion S58), while in coin inscriptions three spellings are attested: ANXIAΛEΩN, AΓCIAΛEΩN and AΓXIΛAEΩN.Footnote 20 Surely to the inhabitants of Anchialos during the Imperial age variant spellings of the name of their city made no difference, even if spelling with -γ- was the most common. In terms of spelling, there was no obstacle preventing the association of Ἀγχιαλός from the Iliad and the Odyssey with the city of Anchialos. Since, as is well known, Greek cities took pride in being associated with figures from the heroic age if this association could be plausibly explained (see e.g. Scheer Reference Scheer and Erskine2003), one can easily imagine linking Anchialos on the Black Sea with a travelling hero of the Trojan war, or with a Phaecian sailor.

Aelian, in a section concerned with philosophers participating in the political life of various poleis, usually as law-givers, names Anaximander as the founder of Apollonia: ᾿Αναξίμανδρος δὲ ἡγήσατο τῆς ἐς ᾿Απολλωνίαν ἐκ Μιλήτου ἀποικίας (ʻAnaximander led colonists from Miletos to Apollonia'; Aelian Variae Historiae 3.17). No source is quoted, and this foundation story, although attractive at first glance, is hard to reconcile with Ps.-Scymnus’ evidence regarding the foundation of Apollonia 50 years prior to the beginning of the reign of Cyrus the Great, i.e. c. 609 bce (Ps.-Scymnus 730–3; also Periplus Maris Euxini 85–6). Since the earliest pottery found in Apollonia (Reho Reference Reho and Fol1986; Bouzek Reference Bouzek, Kacharava, Faudot and Geny2005, 66–7; Nikov Reference Nikov and Avram2009), as well as the earliest graves (Panayotova Reference Panayotova and Tsetskhladze1998; Baralis et al. Reference Baralis and Manoledakis2016, 156), can be dated to the end of the seventh century bce,Footnote 21 a foundation date that falls roughly in this timeframe is acceptable (Musielak Reference Musielak2003, 15–16; Avram, Hind and Tsetskhladze Reference Avram, Hind, Tsetskhladze, Hansen and Nielsen2004, 931; Kacharava Reference Kacharava, Kacharava, Faudot and Geny2005, 12). The earliest inscription from Apollonia is a sixth-century bce boustrophedon epitaph, and this archaic monument lends support to the late-seventh-century date of the foundation of the city (IGB I2 404). Anaximander, born most probably in 611 bce, could not have led the Milesian colonists to Apollonia c. 609 bce.Footnote 22 Aelian's story is hardly a reflection of the authentic tradition on the foundation of Apollonia, but rather an attempt to augment the spectrum of Greek philosophers’ benevolent involvement in public life.

TOMIS: ETYMOLOGY AND MYTHOLOGICAL FOUNDERS

Two Western Pontic cities stand out in the field of foundation stories: Tomis and Mesambria. In both cases, the evidence is ample and in some way distinguished. Tomis is the only city in the region that claimed the attention of a world-class ancient author, Ovid, relegated by Augustus to this city for an unknown crime.Footnote 23 Among the minor themes of his exiled written poetry is the aitiological story regarding the name Tomis, included in the Tristia.Footnote 24 In Ovid's rendition, the etymology of the name Tomis is anchored in the myth of the Argonauts, who fled from King Aietes to the western shores of the Black Sea. In order to slow down the pursuing party, Medea killed her younger brother Absyrtos and dismembered his body, she then placed his head and arms on a hill and scattered the rest of her brother in adjacent fields. This indeed bought time for the Argonauts as Aietes, father of the poor Absyrtos (and Medea), stopped to gather the body parts of his son and bury him properly. Ovid goes on to offer an explanation of the name Tomis by using a play on the Greek word τόμος (ʻslice'), derived from τέμνω (ʻto cut’, hence consecuisse, in Latin): inde Tomis dictus locus hic, quia fertur in illo | membra soror fratris consecuisse sui (‘so this place was called Tomis, because they say it was here the sister cut up her brother's body’; Ovid Tristia 3.9.33–4, trans. Kline Reference Kline2003).

Without going into details, this is a little-known version of the myth, quoted only by Ovid and Ps.-Apollodoros. It was no doubt selected by Ovid, the poeta doctus, precisely because it allowed him to present the place of his exile as cursed from its inception and hence unfit for a cultured human being, like the poet himself.Footnote 25 The Bibliotheke is almost certainly dated later than the Tristia, but nothing indicates that Ps.-Apollodoros might have accessed Ovid.Footnote 26 The story of Absyrtos, abducted and killed by Medea, who scattered his dismembered limbs around, is derived ultimately from Pherekydes (Pherecydes FGrHist 3 F32a and F32b); yet some important details known to Ovid and Ps.-Apollodoros are absent from the surviving fragments of Pherekydes. Unless devised independently by Ovid and Ps.-Apollodoros, they must have been borrowed from a Hellenistic source unknown to us (Nawotka Reference Nawotka and Deroux1994b). The story of the name Tomis is one of the few aitiological myths that explain Black Sea toponyms by referencing Absryrtos’ sorry end, and all of them belong to the realm of antiquarian scholarship.Footnote 27 As far as we can say, neither is reflected in local sources that originated in places whose names are explained in these stories.

Local sources from Tomis record two ktistai. An inscription of the late second to early third century ce reads: [Δ]ιοσκόρους κτίστ[ας τῆς πόλεως τῇ φυ]/λῇ Βορέων ἀνέ̣[θηκεν — — —] (ʻto the Dioskouroi founders of the city, it was set up by the phyle of Boreis'; ISM II 122). In principle, the restored reading [τῆς πόλεως] is not impossible, although it will remain hypothetical until further evidence for the Dioskouroi as founders of Tomis is available.Footnote 28 Far better attested is a youthful hero Tomos, who appears in coin inscriptions called κτίστης Τόμος (‘Tomos the founder’),Footnote 29 ἥρως Τόμος (‘Tomos the hero’),Footnote 30 or simply Τόμος.Footnote 31 Tomos belongs to the company of mythological founders whose names were borrowed from the appropriate toponyms, e.g. Byzas of Byzantium, Pergamos of Pergamon, Mytiles of Mytilene, Romos of Rome, and Xanthos of Xanthos.Footnote 32 These eponymous heroes crop up first in the Hellenistic age, including Pergamos of Epeiros, the eponymous hero of Pergamon who served the Attalid dynasty's need to find ancestors among the great figures of the Trojan war (Scheer Reference Scheer and Erskine2003, 223). Eponymous city heroes became enormously popular under the Roman Empire, in Asia Minor and elsewhere (Mitchell Reference Mitchell1984, 130–1; Strubbe Reference Strubbe1984–6, 258, 279–80).

Tomos is also attested directly in two inscriptions. One, recently published by Avram and Jones and dated to the second half of the second century ce is a metric epitaph for an Euelpistos from Byzantium buried in the city of Tomos: ἄστυ Τόμοιο.Footnote 33 The second, perhaps dated to the second century ce, absent from both the ISM II and the Packard Humanities Institute: Searchable Greek Inscriptions database, is also a metric epitaph, which merits reprinting on account of its near absence in the academic discussion:Footnote 34

The evidence presented in these epitaphs is important: their poetic form far exceeds the minimum standard for a tombstone inscription, in terms of both cultural sophistication and expense for whoever commissioned them.Footnote 36 These were elite tombstones, yet documents of a private nature, unlike coins with the effigy and inscription of the hero/ktistes Tomos, which are strictly public. The epitaphs allow us to catch a glimpse of how the local elite viewed themselves and their city. These two epitaphs show that the metonymic ‘city of Tomos’ (ἄστυ Τόμοιο) for Tomis became, in the second century ce, an expression of choice among some poets working for the local elite members, which marks a willing adoption of the hero Tomos into the perception of self and their city in the Antonine age.

To this evidence, one may perhaps add another inscription from Tomis, a damaged third-century ce list of philotimoi, which reads: [Ἡρα]κλᾶς Τόμου (‘Heraklas son of Tomos’; ISM II 31, col. II, l. 1). The name Tomos is extremely rare, almost unattested outside of Tomis,Footnote 37 and in Tomis it applied almost exclusively to the eponymous founder hero. Hence its presence in this list of philotimoi is significant within the cultural milieu of second- to third-century ce Tomis. The patronymic ‘son of Tomos’ in this inscription stems from the decision (taken two generations prior to the date of this inscription) made by the father of our Tomos to give to his son the name of the founding hero of Tomis. Thus, it strengthens the impression of the importance of the ktistes/hero Tomos, as viewed by the elites in Tomis during the second century ce. Alexandru Avram (Reference Avram2018, 460) wants to provide additional evidence for Tomos, restoring a heavily damaged line 7 in an elegiac epitaph of the first or second century ce as: [πατρί]δος ἔκ τε̣ Μ̣υ[σῶν? δ᾿ ἦλ/θο]ν ἐς ἄστυ Τ[όμου] (‘I came to the city of Tomos from my native Mysia’), rather than the [πατρί]δος ἐκ Τε̣μ̣ύ[ρας δ᾽ ἧλ/θο]ν ἐς ἄστυ τ[όδε] (‘I came to this city from my native Temyra’) of the first editor of the inscription, Werner Peek (StudClas 6, 1964, 132–3 = SEG 25.807). Both readings are conjectural, hence it is not possible to use any of them as evidence for Tomos.

The last issue to be addressed is the date and probable circumstances of the introduction of the legend of Tomos ktistes in Tomos itself. All of the evidence for Tomos is dated to the second and third centuries ce, and the earliest coins date no earlier than the reign of Marcus Aurelius; therefore in an earlier paper, I opted for the age of Antoninus Pius as the earliest possible date for when the story of Tomos was born (Nawotka Reference Nawotka and Deroux1994b, 414–15). According to Avram and Jones, the date is much earlier. They quote a dedication of a heroon of the first half of the second century ce which commemorates the restoration of freedom (i.e. the status of civitas libera et immunis) to Tomis ([ἀποκαθ]εσταμένης τῆς ἐλευθερίας [‘when freedom was restored’]), which they convincingly link with Hadrian due to another inscription from Tomis that reads Eleutherios, Olympios, and Soter.Footnote 38 The dedication mentions an altar of the heroon ([π]ρὸς τῷ βωμῷ τοῦ ἡρῴου), which according to Avram and Jones must be the heroon of Tomos. If their reading of the intention of the dedicators of the heroon is correct, this inscription would push the date of the inception of the myth of Tomos ktistes to the age of Hadrian, when indeed similar foundation stories proliferated in the Greek world (Avram and Jones Reference Avram and Jones2011, 132–3). This reconstruction is probable, but not certain, on account of a dearth of solid evidence for Tomos (not just for a hero) preceding Marcus Aurelius. Avram and Jones's idea that what happened under Hadrian amounted to a reinvigoration and official recognition of the long-existing foundation myth of Tomos borders, however, on the speculative. In his later papers, Avram (Reference Avram, Cojocaru and Schuler2014, 165; Reference Avram, Grammenos and Petropoulos2018, 458–9) is more inclined to attribute the birth of the legend of Tomos, the founder of Tomis, to the age of Hadrian. In the light of currently available sources, this date is as likely as the age of Antoninus Pius.

MELSAS, THE FOUNDER OF MESAMBRIA

In terms of the amount of evidence, Mesambria has the most impressive dossier of literary sources on its toponym, often combined with a foundation story. It was noticed long ago that literary and documentary evidence regarding city founders rarely overlaps, and that in most cases only local documentary evidence provides proof for a founder cult (Di Segni Reference Di Segni1997, 147). In the Western Pontus, the only foundation story to enjoy the support of both literary and documentary evidence is that of Melsas, the founder of Mesambria. The story is first mentioned by Nikolaos of Damascus and Strabo, whose accounts were near contemporary and most probably independent of each other:

Nikolaos:

Μεσημβρία, πόλις Ποντική. Νικόλαος πέμπτῳ. ἐκλήθη ἀπὸ Μέλσου. βρία γὰρ τὴν πόλιν φασὶ Θρᾷκες. ὡς οὖν Σηλυμβρία ἡ τοῦ Σήλυος πόλις, Πολτυμβρία ἡ Πόλτυος [πόλις], οὕτω Μελσημβρία ἡ Μέλσου πόλις, καὶ διὰ τὸ εὐφωνότερον λέγεται Μεσημβρία. (Nicolaus of Damascus FGrHist 90 F43, ap. Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Μεσημβρία)

Mesembria, a Pontic city. Nikolaos (says so) in the fifth book. For Thracians say bria for city. As Selymbria is a city of Selys, Poltymbria a city of Poltys, so Mesembria is a city of Melsos, which is pronounced Mesembria on account of more pleasant sound.

Strabo:

εἶτα Μεσημβρία Μεγαρέων ἄποικος, πρότερον δὲ Μενεβρία, οἷον Μένα πόλις, τοῦ κτίσαντος Μένα καλουμένου, τῆς δὲ πόλεως βρίας καλουμένης θρᾳκιστί⋅ ὡς καὶ ἡ τοῦ Σήλυος πόλις Σηλυμβρία προσηγόρευται, ἥ τε Αἶνος Πολτυμβρία ποτὲ ὠνομάζετο.

then Mesembria, a colony of the Megarians, formerly called ‘Menebria’ (that is, ‘city of Menas’, because the name of its founder was Menas, while ‘bria’ is the word for ‘city’ in the Thracian language. In this way, also, the city of Selys is called Selymbria and Aenus was once called Poltymbria).Footnote 39

The etymology of the name Mesambria also appears in the work of four Byzantine authors, three times in Strabo's version,Footnote 40 and once without any clear reference to the name of the alleged founder (Constantinus Porphyrogennitus, De thematibus, 2.1 [934–44]). The authors who followed Strabo must have consulted Nikolaos and/or Stephanus, since they convey the same information, absent in Strabo, that the alleged original name of Mesambria was changed to facilitate pronunciation. None of these late sources contain any information about the founder of Mesambria, which likely originated outside of Strabo and Stephanus; thus their value as a source on the origin of the story of Melsas/Menas is negligible. We have, however, one more piece of evidence, a second-century ce epitaph from Mesambria which reads: Ἰουλία Νεικίου | θυγάτηρ μεγαλέτορος ἀνδρός, | Μεσεμβρία δέ μυ πατρὶς ἀπὸ [Μ]έλσα καὶ βρία (ʻIoulia daughter of Neikios a man of great heart. My hometown is Mesambria (whose name is derived) from Melsa and bria'; IGB I2 345, ll. 4–7). First, this swings the balance regarding the spelling of the name of the founder of Mesambria in the direction of Nikolaos; Strabo's text is almost certainly corrupt, with the original -λσ- becoming -ν- due to a scribal error in an early stage of transmission.Footnote 41

A quarter of a century ago I argued that the assimilation of -λσ- into -σ- in the name of Melsambria into Mesambria alleged by Nikolaos of Damascus is linguistically impossible due to the Doric dialect of Mesambria (Nawotka Reference Nawotka1994a). This assimilation theory is also superfluous, as names with -λσ-, although not very common, are quite well attested in the Pontic and Thracian regions, e.g. Δοιδαλσης, घάλσις, घβελσουρδος, Κέλσος, Κελσῖνος, Μελσέων, Τυρελσης (IGB Ι2 47bis, 308sexies; II 737; ΙΙΙ.1 1317; III.2 1478, 1496, 1516, 1517, 1593, 1666, 1690, 1741; IV 2017, 2074, 2216, 2217; V 5103; IPE I2 200; SEG 35.832; Slavova Reference Slavova and Vottéro2009, 214–16; Stoyanov Reference Stoyanov, Tzochev, Stoyanov and Bozkova2011, 193, 198–9; Castelli Reference Castelli2015, 97–8; cf. D. Dana Reference Dana2014, 155, 382). The ΜΕΛΣΑ coins (below) give additional support to the existence of the name Melsa(s) in Hellenistic Thrace; so there is now even less doubt that the alleged assimilation of the putative Melsambria into Mesambria ever occurred.

A small bronze coin bearing the inscription ΜΕΛΣΑ has surfaced in recent years (Fig. 2). This inscription appears on three specimens that form part of museum collections in Varna and Athens (KIPKE collection, Benaki Museum), as well as on a number of specimens held in private collections, reportedly totaling 28 specimens altogether (Stoyas Reference Stoyasforthcoming). The coin in question has been published by Topalov and Stoyas.Footnote 42 Reportedly, there is also a larger coin with the same inscription, but in Stoyas’ view, the denomination of all ΜΕΛΣΑ coins was the same, despite their weight varying between 2.5 and 6.8 grams (Stoyas Reference Stoyas, Paunov and Filipova2012, 158). The smaller coin has a filleted bucranium on the obverse and a fish above the inscription ΜΕΛΣΑ on the reverse. To my knowledge, no doubt has ever been expressed regarding the authenticity of these coins. On the contrary, important circumstances speak to the authenticity of ΜΕΛΣΑ coins: almost all known specimens come from a well-defined area between Cape Shabla (нос Шабла) and the town of Shabla (Шабла) on the Bulgaria coast of the Black Sea; some specimens are worn, which indicates their long circulation; and the existing specimens were struck with more than one pair of dies.Footnote 43 The archaeological context of the coins is unknown; most of them are kept in Bulgarian museums and private collections. At least six specimens contain overstrikes: of Philip II, Alexander the Great, Kassander, and one unidentified ruler. The overstrikes on Kassander's coins would give 316–305 bce as the terminus a quo of the whole series unless the unidentified specimen was issued by Antiochos II. Based on iconographic evidence and his reconstruction of the political situation on the south-western coast of the Black Sea, Stoyas (Reference Stoyasforthcoming) tentatively dates ΜΕΛΣΑ coins between 313 and 291 bce.Footnote 44 The area from which the ΜΕΛΣΑ coins reportedly come from corresponds to the ancient location (an emporion?) of Karon Limen, which is located to the north of the town of Kavarna on the Black Sea coast, i.e. approximately midway between ancient Bizone and Dionysopolis (Stoyas Reference Stoyasforthcoming).

Fig. 2. ΜΕΛΣΑ coin. Courtesy of the KIPKE Foundation, Athens.

The coin inscription is probably, in keeping with Greek standards of numismatic epigraphy, in the genitive and states the name of the minting authority; in other words, it is a coin of a Melsas. A conventional identifier on the coin would represent either the city that housed the mint or a king/tribal leader who was named as the minting authority. Topalov (Reference Topalov1998; Reference Topalov2007, 289–302) raised a number of contradictory hypotheses as to who or what ΜΕΛΣΑ signifies: a Thracian chieftain or a city called Messa or Melsa, which in his opinion was located in the place where Anchialos later stood. After his thorough analysis of source-based and circumstantial evidence, Stoyas rightfully rejects Mesambria (Melsambria of Nikolaos), Anchialos (Messa of Pliny), Karon Limen, Naulochos, and Bizone, which were all located on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast, as places that housed the mint which issued the ΜΕΛΣΑ coins (Pliny Historia Naturalis 4.45; Stoyas Reference Stoyasforthcoming). His earlier hypothesis (Stoyas Reference Stoyas, Paunov and Filipova2012, 161–6) placing the mint in the area of Byzantium is untenable when one considers the place where most ΜΕΛΣΑ coins were found; Stoyas correctly no longer subscribes to this view. If ΜΕΛΣΑ does not refer to the toponym of the place (city) where the coins were minted, it most probably refers to the name of an official from the mint, a ruler, or a mythological figure. According to Karayotov, Melsas was the Thracian oikistes of Mesambria. Apart from referring to Strabo and Nikolaos of Damascus, Karayotov, following in the footsteps of Gerasimov, seeks to identify a portrait of Melsas on the coins. He theorises that Melsas is the figure that appears in profile wearing a helmet on bronze coins that also include a pelta and the inscription ΜΕΤΑ on their reverse, and that he also appears on an uninscribed fifth-century bce drachma coin, wearing a Corinthian helmet.Footnote 45 Karayotov (Reference Karayotov2009, 99–102) also makes Melsas a Thracian king-priest in the manner of Getan Zalmoxis. There is no supporting evidence for anything in this interpretation, and since ΜΕΤΑ is surely an abbreviation of the name of the city (with the letter Τ [sampi] having the phonetic value of -σσ-) and not the name of the founder (Nawotka Reference Nawotka1994a; Slavova Reference Slavova and Vottéro2009, 200; Castelli Reference Castelli2015, 97–8), in addition to the image on the obverse generally being interpreted as Athena (Head Reference Head1911, 278; Robu Reference Robu2014, 320–1), it is better to leave Karayotov's hypothesis alone.

Stoyas (Reference Stoyasforthcoming) shows that the iconography of the ΜΕΛΣΑ coin has no adequate parallel that would allow it to be attributed to a king/chieftain. In his opinion, certain features of the coin's iconography, the filleted bull's head in particular, would better suit a mythological figure than a king. And if so, the issuing authority of ΜΕΛΣΑ coins might be a non-urban sanctuary of the hero Melsas. Stoyas further tries to link ΜΕΛΣΑ coins with the political events of the late fourth century bce, in particular the war fought by Lysimachos in this area. This is an attractive explanation of the circumstances regarding the minting of ΜΕΛΣΑ coins and the meaning behind their iconography and inscription(s), but without supporting evidence it remains a hypothesis only.

From the point of view of this paper, the most important issue is whether the Melsas associated with the coin can be construed as the historical founder of Mesambria. The chronology of this coin, convincingly established by Stoyas as early Hellenistic, speaks against it, since Mesambria was founded in the late sixth century bce, i.e. some 300 years prior to the minting of the coin. Archaeology provides another reason for rejecting this hypothesis. A Thracian settlement was found beneath the earliest strata of the Greek city, but a hiatus precluded the continuation of habitation from the Thracian to the Greek city (Alexandrescu and Morintz Reference Alexandrescu and Morintz1982; Petrova Reference Petrova and Manoledakis2013, 125; Robu Reference Robu2014, 319; Damyanov Reference Damyanov, Valeva, Nankov and Graninger2015, 301). Without continuous habitation and the gradual transformation of the city from native to mostly Greek, there is little chance that the story of a Thracian king (or founder) would survive the age of Greek domination in Mesambria. As I pointed out earlier, Melsas of the foundation myth known from Nikolaos and Strabo is a literary figure whose story was most likely penned by a local historian of the late Hellenistic age (Nawotka Reference Nawotka1994a, 325–6; Dana and Dana Reference Dana and Dana2001–3, 104–5; Mainardi Reference Mainardi2011, 6–7).

Where then does this leave the Melsas that appears on the coin that was surely minted close to Mesambria in the late fourth or early third century bce? It is hard to believe that the early-Hellenistic Melsas from the coin may have gone unnoticed in Hellenistic Mesambria. The opposite is almost certainly true, especially when one considers that the Melsas-derived name Melseon is well attested in Hellenistic Mesambria;Footnote 46 it appears in amphora stamps dated to the third and second centuries bce and represents a magistrate or a potter (Garlan Reference Garlan2007, no. 104; Slavova Reference Slavova and Vottéro2009, 214–16; Stoyanov Reference Stoyanov, Tzochev, Stoyanov and Bozkova2011, 193, 198–9; cf. Petrova Reference Petrova and Manoledakis2013, 125; Robu Reference Robu2014, 318–19; Castelli Reference Castelli2015, 97–8). Melseon also appears in fourth- and third-century bce stamps on amphorae of an unknown origin found in Seuthopolis (SEG 35.832, nos 42, 43), but possibly originating from Mesambria (Balkanska and Tzochev Reference Balkanska, Tzochev and Gergova2008; Stoyanov Reference Stoyanov, Tzochev, Stoyanov and Bozkova2011, 192–3). Stone inscriptions attesting this name in Mesambria begin in the third century bce,Footnote 47 continuing in the second and first centuries bce.Footnote 48 The name Polyxenos, son of Melseon, an euergetes of Dionysopolis, is known from a late second or early first century bce honorific decree from Dionysopolis (SEG 59.730). This person may, in fact, be identified with a strategos of Mesambria.Footnote 49 Attestations of the Melsas-derived name Melseon in stone and pottery inscriptions exclusive to Mesambria (or related to the city) are significant with regards to the discussion concerning the symbolic presence of Melsas in Hellenistic Mesambria. This concentration of evidence suggests that the memory of Melsas, either as a historical or mythological figure from a neighbouring tribe, was still alive in late-Hellenistic Mesambria when the aitiological story of Melsambria becoming Mesambria was born.

FOUNDATION MYTHS OF THE WESTERN PONTUS

The late-third-century ce author Menander Rhetor states that one way of praising a city is through its founder, concluding: οὐσῶν δὲ τούτων τῶν αἰτιῶν καὶ τοιουτοτρόπων εἰδέναι σε χρὴ ὅτι ἐνδοξόταται μὲν αἱ θεῖαι, δεύτεραι δὲ αἱ ἡρωϊκαί, τρίται δὲ αἱ ἀνθρωπικαί (ʻSo these and of this kind are the origins of cities and you should know that the most honourable are divine foundations, the second best are heroic, and the third human'; Menander Rhetor, in Spengel Reference Spengel1856, 358–9). He further elaborates that among the original settlers, the most honourable are the Greek tribes, next, the famous barbarians (to whom the Thracians surely belong, even if Menander does not mention them by name), with the least honourable being the Romans, on account of their foundations being the most recent (Menander Rhetor, in Spengel Reference Spengel1856, 354, 358–9). The foundation and aitiological stories from the Western Pontus fit perfectly with Menander's recipe for praising a city: most recorded founders are either gods or heroes-turned-gods (Dionysos, Herakles, Dioskouroi, Thracian Horseman); there are also regular heroes (Tomos and Melsas and perhaps Anchialos), and one mere mortal (Anaximander).Footnote 50 None of these accounts relate to a genuine tradition regarding foundation; most are just stories that are similar to their counterparts in Asia Minor and elsewhere, with the possible exception of the tale of Melsas, which probably preserves elements of non-Greek tradition.

The two best-documented foundation/aitiological stories, i.e. those concerning Tomos and Melsas, share certain characteristics but differ in other respects. The most obvious common characteristic is that, as we know from inscriptions, they both had a life outside of the official propaganda that appeared on municipal coinage. The time and circumstances of their introduction were quite different. The story of Tomos belongs to the most common type of foundation myth of the Antonine age, that of a hero named after the relevant toponym. Its introduction in the second century ce coincides with the time when Tomis was most prominent in the region. The city, endowed with enviable honorific titles such as λαμπροτάτη (‘most splendid’; ISM II 92, 96, 97, 105), πρώτη (‘first’; ISM II 97), and μητρόπολις (‘metropolis’ or ‘capital city’),Footnote 51 was the seat of the Western Pontic koinon and host to scores of Roman magistrates, although probably not to the praefectus orae maritimae.Footnote 52 The introduction of the aitiological story of ktistes Tomos, and its broad acceptance among the local elite, was a manifestation of the same civic pride that emanates from the honorific titles and leadership position Tomis enjoyed in the Western Pontus during the Antonine and Severan periods. The late-Hellenistic – as it seems – story of Melsas, the founder of Mesambria, is much earlier than other foundation myths in the Western Pontus and uniquely preserves an early-Hellenistic, non-Greek tradition, although in a much-transformed form. It is also quite uncommon in attributing the genealogy of a Greek city to a non-Greek, other than a Hellenistic king.Footnote 53

For all his attestations in literary and epigraphic sources, Melsas is conspicuous for his absence from the coinage of Mesambria. This is in stark contrast to some other well-documented cases in the region, where the founding heroes of Tomis, Kallatis and Anchialos were celebrated on coins. Building a case on the silence of sources is always tricky, especially since one can never be sure whether a yet-unknown coin from Mesambria may surface on the market. This is of course possible but not very likely, bearing in mind how well published the coinage of Mesambria is (Karayotov Reference Karayotov2004; Reference Karayotov2009). If no coin with a portrait and inscription of Melsas, the founder of Mesambria, comes to light, the evidence will point to divergent approaches being used to craft foundation stories in Mesambria and most other Greek cities in the region. Placing the effigy of its founder on its coins, accompanied by his name and the title κτίστης, signified a policy-statement by the polis; the same is true of referring to the mythological founder of a city in inscriptions carved in the name of the demos/patris, as is the case with Dionysos, the founder/namesake of Dionysopolis and perhaps with the Dioskouroi in Tomis.Footnote 54 The official founders were a Greek god (Dionysos in Dionysopolis), a great hero (Herakles in Kallatis), a lesser figure of impeccable Homeric credentials (Anchialos in Anchialos) and an etymological hero (Tomos in Tomis), all of whom testified to the strong Greek credentials of the colonial cities founded on the margins of the Greek world. This was the most common strategy, in the Western Pontus and elsewhere.Footnote 55

It seems that sometimes an alternative approach to the foundation story can be identified. The prime example is that of the Thracian hero Melsas of Mesambria, so far known from non-official sources only. The Thracian Horseman celebrated as ktistes in the private dedication from Kallatis may belong to the same realm (ISM III 93): of accommodating local Thracian figures, surely perceived as autochthonous, into image-building of a Greek city on Thracian shores. With the striking absence of the recognition of Melsas by the polis as founder/namesake of Mesambria, we cannot be sure if he was indeed part of the official image-building of the city as is generally, if tacitly, assumed. If this was so, we may try to identify reasons why the people of Mesambria chose a (semi-)legendary Thracian figure as their official founder. Was it meant to form an ideological counterpart to the relative political success of late-Hellenistic Mesambria, which, quite uniquely in the region, managed to preserve independence and prosperity in the age of Burebista's and other invasions (Nawotka Reference Nawotka1994a, 326)? Or was it created to accentuate the property rights of Mesambria to the surrounding land (Petrova Reference Petrova and Manoledakis2013, 127)? Or was it an attempt by Mesambria to integrate itself into the world of local mythological genealogies (Robu Reference Robu2014, 320–1)? Or was it to make political gains over the Thracian tribes (Castelli Reference Castelli2015, 98)?

The alternative version is also possible: there are no official attestations of Melsas in Mesambria simply because Melsas was not an officially recognised founder of the city. Our evidence may suggest that the story of Melsas was devised by a private individual, drawing from tales of a mythological Thracian figure (hero?) present in the Western Pontus from the early third century bce at the latest. This happened in an age that, in general, saw the Western Pontus gradually accepting, on an ideological level, its Thracian neighbours, which is demonstrated by the introduction of local cults such as those of the Thracian Horseman, Karabazmos, Manimazos and Darzalas (Danov Reference Danov and Descoudres1990, 155; Gočeva Reference Gočeva1996; Nawotka Reference Nawotka2001, 129–30; Damyanov Reference Damyanov, Valeva, Nankov and Graninger2015, 304). Thus the case of Melsas is another example of the well-known phenomenon of cultural transfers between Western Pontic Greeks and the majority Thracians.Footnote 56 The story of Melsas proved attractive to some members of the local elite over the next 200 years, as we learn from the verse epitaph of Iulia, daughter of Neikos (IGB I2 345 of the second century ce).

At present this is as far as one can proceed in explaining the phenomenon of Melsas strictly on source-based grounds. If indeed, as I try to argue here, Melsas was not an official founding hero of Mesambria, his case strengthens the argument for cultural transmission in the Black Sea area in the Hellenistic age. Certainly, it was not a one-way phenomenon, conventionally called Hellenisation, amounting to the spreading of Greek culture, religion, and language over local peoples. The adoption in Mesambria of the story of Melsas in the early Hellenistic age and its longevity, attested by the constant usage of Melsas-derived names in this city and the late-Hellenistic status of Melsas as a founding hero, seem to point to a parallel process: the Greek-writing inhabitants of Mesambria being aware of cultural and religious development in neighbouring Thracian lands and willing to borrow from them to the point of grounding their identity in a made-up story of a Thracian founder of their city. The case of Melsas, the Thracian founding hero of a Greek city, further proves the complexity of cultural contacts and building identity in a seemingly uniform world of Greek colonies on the western shores of the Black Sea.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My research on this paper was supported by a grant from the National Science Centre, Poland: UMO-2014/14/A/HS3/00132. I would like to thank Mr Lucas Griffin for undertaking the laborious task of correcting my English. I would like as well to acknowledge the friendly assistance of Dr Małgorzata Eder-Dusza, who translated my abstract into Greek, and of Dr Joanna Porucznik, who drew the map for this paper. An earlier (and shorter) version of this paper was presented in July 2018 at the conference ‘Power, status and symbols in the Black Sea area in antiquity’, Wrocław, Poland. I would like to thank the participants for their friendly criticism, which has helped me to make my point clearer. My greatest thanks go to Yannis Stoyas of the KIPKE Foundation in Athens, who shared with me his remarkable knowledge on the Melsas coin and Thracian numismatics in general, and who supplied me with a picture of this coin and allowed me access to his paper on Melsas, still awaiting publication in the conference acts.