I. RESEARCH IN THE REGION OF AGIOS VASILEIOS, CHALANDRITSA

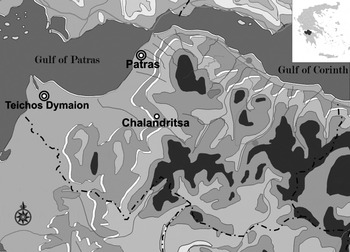

The earliest research in the area of Chalandritsa was carried out in 1928 by N. Kyparissis, who excavated on the Troumbes hill ‘a cemetery with three tumulus-like constructions that included tombs built with slabs’ (Kyparissis Reference Κyparissis1928, 110–19) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 no. 2). One tomb yielded finds that indicated a Mycenaean date for the initial construction and use, followed by reuse in the Late Geometric period.Footnote 2

Fig. 1. Achaea.

Fig. 2. The Chalandritsa region. 1 Agios Vasileios; 2 Troumbes; 3 Stavros; 4 Kamini; 5 Skoros; 6 Ai Lias; 7 Katarraktis.

In the years that followed, Kyparissis excavated chamber tombs in the cemetery at Agios Vasileios, c.700 m south of Troumbes hill (Kyparissis Reference Κyparissis1929, 89–91; Reference Κyparissis1930, 85) (Fig. 2 no. 1). From 1989 onwards, sporadic rescue excavations were carried out by the 6th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities following repeated incidents of looting (Stavropoulou-Gatsi and Petropoulos Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi and Petropoulos1989, 134–6; Petropoulos Reference Petropoulos1990, 504–5; Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1991, 147; Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1993, 123; Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1994, 234; Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1995, 217; Petropoulos Reference Petropoulos1999, 262). In 1985, a Mycenaean settlement was located in the same region, at Stavros, Chalandritsa, 1.5 km east of the cemetery; much of it has now been excavated (Kolonas Reference Kolonas1985, 136–8; Reference Kolonas and Rizakis2000, 93–8; Kolonas and Gazis Reference Kolonas, Gazis and Kazakou2006, 25–30; Kolonas Reference Kolonas2008, 7–13) (Fig. 2 no. 3). Today Chalandritsa, with the cemetery to the west and the settlement to the east, is one of the most significant Mycenaean sites in western Achaea.

In the Geometric period, activity is attested at a number of sites in the broader region (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, passim; Reference Gadolou and Vlachopoulos2012, 40–5). A Late Geometric tomb was found at Kamini, near Platanovrysi, 4.5 km west of Chalandritsa (Mastrokostas Reference Mastrokostas1964, 186; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 138 oinochoe no. 131 AMP 653a) (Fig. 2 no. 4).

Nearby, at Skoros, to the south-east of Troumbes hill, further Late Geometric tombs were located (Mastrokostas Reference Mastrokostas1961–2a, 129; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 125–8 nos. 105, 106, 106a, figs. 98–9) (Fig. 2 no. 5), and a plain pithos burial was found in Marnolakka gorgeFootnote 3 (Yialouris Reference Yialouris1960, 138; Mastrokostas Reference Mastrokostas1961–2a, 129). Finally, south-east of Chalandritsa, investigation of a looters' pit in the hill of Ai Lias revealed numerous black-glazed and a few Geometric sherds (Petropoulos Reference Petropoulos1991, 157) (Fig. 2 no. 6). A number of other Geometric sites have been located beyond Chalandritsa, along the road to and around Katarraktis, where the terrain becomes more mountainous and rugged (Zapheiropoulos Reference Zapheiropoulos1952, 401–6; 1956, 196–7; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 128–37 nos. 107–28, figs. 100–12)Footnote 4 (Fig. 2 no. 7).

The pottery presented in this article, which came to light during study of the Mycenaean chamber tomb cemetery at Agios Vasileios, is assessed on the basis of parallels from the area of the ‘western koine’ (predominantly Achaea, also Aetoloakarnania, Elis, Ithaca and Messenia). It is dated according to the chronological subdivisions proposed by Gadolou (Reference Gadolou2008, 26–7), namely: Protogeometric (975/950–850 bc), Early Geometric (850–800 bc), Middle Geometric (800–750 bc), Late Geometric (750–700 bc).Footnote 5 Thus, certain finds which evidently belong to the Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric transition are dated to the mid-ninth century bc.

Study of the Submycenaean and Protogeometric periods in Achaea is ongoing, and publication of new data from stratified Mycenaean settlements, such as that at Stavros, Chalandritsa, is awaited. The prevailing view is that the settlement was abandoned during the Submycenaean–Protogeometric transition (Moschos Reference Moschos, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009, 243, phase 6a or early 6b). The present article provides new data from the cemetery for Early Geometric, a period previously unknown in the region of Chalandritsa.

II. SURFACE FINDS OF POST-MYCENAEAN DATE WITHIN THE MYCENAEAN CEMETERY

Notes in the excavation diaries and excavators' reports of Hellenistic and Roman sherds and tile fragments, along with remains of mud brick walls, suggest the existence of a post-Mycenaean settlement within the limits of the cemetery (Stavropoulou-Gatsi and Petropoulos Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi and Petropoulos1989, 136; Petropoulos Reference Petropoulos1990, 505). In addition, surface finds collected very close to the tomb cluster investigated by Kyparissis include sherds of cooking pots and coarse ware, sherds in brown fabric with signs of black paint, tile fragments, a pyramidal loomweight, and flint flakes. A small number of Geometric sherds was also collected, though far fewer than those found within the tombs.

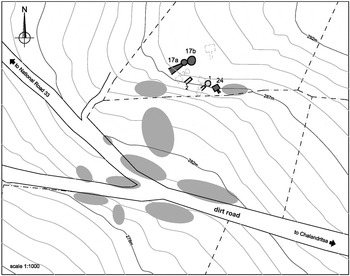

Further finds were made in the area of Tombs 1 and 2 (Fig. 3), which lie very close to Tombs 17 and 24 (to the south and west of these respectively), the larger volume of evidence from which is presented below.

Fig. 3. Topographic plan of the cemetery showing Tombs 1, 2, 17 and 24. The light grey areas indicate the location of other Mycenaean tombs in the cemetery.

Tomb 1: despite the fact that the dromos fill contained almost exclusively Mycenaean pottery, a large pithos fragment found during the removal of the final level was, according to the excavator, not of Mycenaean date. In addition, a number of black-glazed sherds, plus one sherd of a Geometric kantharos, were found in a hollow in the bedrock above Tomb 1.

Tomb 2: a north–south wall of limestone and thick roof tile fragments (1.9 m long × 0.52 m wide × 0.35 m high) built on the face of Tomb 2, just above the entrance, was brought to light when the bedrock was first exposed in order to locate the chamber tombs. The wall had cut and partly destroyed the face of the tomb (Fig. 4), and is thus later, although no indications of its date were found.

Fig. 4. The later wall that ‘cut’ the face of Tomb 2. Top left: view from the south-west. Bottom left: view from the south-east. Right: ground plan and elevation of the tomb.

In 1999, a small Archaic black-glazed oinochoe was found in a deposit from a looted tomb chamber (Petropoulos Reference Petropoulos1999, 262),Footnote 6 on the north side of the dirt road within the limits of the Mycenaean cemetery (Fig. 3).

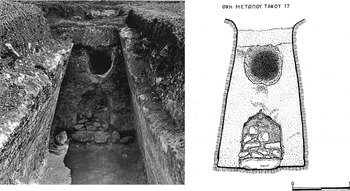

III. CHAMBER TOMB 17Footnote 7

Excavation of Tomb 17 began in 1989 from the 7.05 m long dromos, the fill of which was excavated down to the floor in 11 levels (the first 0.3 m thick and the remaining 10 c.0.2 m thick). A shaft dug by looters reached down to the fourth level (0.7–0.9 m from the surface); hence the first four levels were considered to be disturbed (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, looters' shaft a΄). Finds in those four levels included mainly Mycenaean sherds with some Geometric, flint flakes, part of an obsidian blade, a whetstone, a large fragment of roof tile, and a very few pithos fragments. The excavation diary records that from the fourth level down ‘the deposit does not seem to be disturbed’.

Fig. 5. The facade of Tomb 17 with its blocking wall and above it the looters' shaft a΄, as found. The drawing (right) is based on the excavation diary, sketches and photographs.

Fig. 6. Section of Tomb 17. From the left: the unexcavated part of the dromos fill, Burial I in front of the facade, the looters' shaft a΄ on the facade and the looters' shaft b΄ through the chamber roof, the row of stones on the chamber floor and the three stones found on top of one another below the niche, where the small hydria, catalogue no. 24, was found. The horizontal dotted line inside the chamber indicates the height of the fill.

From the fifth level down, excavation was confined to the three metres in front of the facade (Fig. 6) due to time constraints and the rescue character of the investigation. The first signs of human Burial I appeared at the transition between levels four and five (c.0.90–0.95 m below the surface). The diary notes that ‘the skeleton [is] apparently inside a pit’. Fragments of the skull were found 1.05 m from the facade, with the remains of the skeleton 0.30–0.35 m closer to it. Objects among the bones included: a kantharos (catalogue no. 1, Π1 / ΑMP 16516), a skyphos (catalogue no. 2, Π2/ΑMP 16517), fragments of a handmade jug (catalogue no. 3, Π3 / ΑMP 16518), and a kantharos (catalogue no. 4, Π4–Π5 / ΑMP 16534). Directly below Burial I, a pile of haphazardly placed stones (0.6 m long × 0.28 m wide × 0.3 m tall) lay at the bottom of level five and throughout level six, immediately above the tomb entrance.

Between the stones were the remaining finds belonging to Burial I: a skyphos (catalogue no. 5, Π6 / ΑMP 16533), a kantharos (catalogue no. 6, Π7 / ΑMP 10612) and a conical base from another similar kantharos (catalogue no. 7, AMP 17050). In addition to the pottery presented here, the pottery groups from levels four to six contained numerous Geometric and several Mycenaean sherds.

Levels six to eleven (1.10–2.25 m below the surface) contained much Mycenaean pottery (including sherds of large amphorae, stirrup jars, kraters and coarse wares) plus flint flakes. A few Geometric sherds (with thick and thin walls) were present in level seven (at a depth of 1.3–1.5 m). The dromos floor was reached at a depth of 2.25 m below the surface.

The tomb entrance (1.05 m high) became apparent in level seven: the upper section of the blocking wall was missing and only the four lower rows of stones were in place (Fig. 5).Footnote 8 Sherds from the blocking wall were mainly Mycenaean (from large amphorae, an alabastron, a kylix body and several small open vases), but a few Geometric fragments were also found, from which the kantharos (catalogue no. 8, ΑMP 10610) is restored.

Although the looters failed to gain access to the tomb chamber via the shaft in the facade, they did so by opening a hole in the roof (Fig. 6, looters' shaft b΄). However, they were then able to disturb and loot only an area in the north-west side of the chamber because they were impeded by the sediment and debris which had accumulated in antiquity (the 2 m-high chamber contained 1 m of fill). The ‘looters’ debris' (group OM13), and the first three 0.2 m-deep levels (OM14, OM15 and OM16) which were also partly disturbed by the looters, contained Mycenaean as well as Geometric sherds, some coarse ware, and a number of flint flakes. A few human bones were also found in the third level, higher than the chamber floor.

The succeeding, fourth, level comprised, from top to bottom, a layer of mudFootnote 9 with Mycenaean and Geometric sherds (OM17) and a layer of randomly placed stones, which appeared next to the entrance and reached the opposite east side of the chamber. The upper part of the burial stratum was also revealed at the bottom of the fourth level, mixed with the layer of stones. Level five (0.8–1 m) included the burial stratum, with accompanying Mycenaean vases, snails, flint flakes, stone buttons, a few pieces of charcoal, sherds (OM18) and a bronze fragment (X1). Two probably secondary Mycenaean burials (Burials II and III) were found in the southern part of the chamber (Fig. 7 inside the chamber). These finds were made among, but mainly beneath, the layer of stones, which was removed in order to recover the artefacts and skeletal remains. One final, very thin, level, removed during cleaning of the burial stratum, included exclusively Mycenaean material.Footnote 10 Pottery in the burial stratum dates to Late Helladic ΙΙIA2 – Late Helladic ΙΙΙC middle.

Fig. 7. Ground plan of Tomb 17. Burial I in the dromos and the Mycenaean burial layer with Burial II in the chamber are not at the same level (see Fig. 6 section). Also shown is the niche with vase catalogue no. 24 at the eastern end of the chamber.

As the excavator notes, the stones in layer 4 had not fallen from the blocking wall (they were not found near the wall inside the chamber), but formed an unusual row on the floor leading from the entrance towards the back of the chamber to the north-east to east, where they were found ‘stuck’ against the chamber wall. Three stones were almost on top of each other c.0.85 m above the chamber floor. At this point (0.92 m from the floor) there was a niche in the chamber wall opposite the entrance, which contained the small hydria (catalogue no. 24, Π17 / ΑMP 14677, Fig. 8: Stavropoulou-Gatsi and Petropoulos Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi and Petropoulos1989, 136) along with some Geometric sherds and a bronze fragment (X2). Further investigation of the niche revealed that it also contained stones (including bedrock fragments), sherds (OM20), a fragment of a Mycenaean stirrup jar and four small fragmented and poorly preserved bone fragments (ΟΣ12), plus dark brown earth. Preliminary analysis of the bones by Olivia A. Jones indicates that one appears to be a shaft fragment of a human distal radius. Further study is required to determine whether the other pieces are animal or human. The vases (catalogue nos. 25, Π21 / AMP 16535, and 26, Π22 / AMP 16536) were restored from a selection of the sherds. Because the niche proved difficult to excavate from inside the chamber, a trench was dug down from the surface to the point where it was calculated that it would encounter the niche (Fig. 6). Since no bedrock was encountered at this point, six 0.2 m-thick levels were excavated until the expected depth of the niche was reached. Almost all levels contained flint flakes, small fragments of roof tile, and Mycenaean and Geometric sherds. Notable finds in the fourth level include fragments of the neck of an amphora (catalogue no. 27, ΑMP 16530), and of miniature vases (catalogue nos. 28–31, ΑMP 16531 a, b, c, ΑMP 16537, ΑMP 16538, AMP 16539).

Fig. 8. The small hydria, catalogue no. 24, as found inside the niche. Bottom left: two stones, one on top of the other.

The general picture led the excavator to conclude that the niche could be a side chamber of Tomb 17: it was thus numbered 17b in the excavation diary (Fig. 3). Further systematic research was planned, but unfortunately did not proceed, for reasons beyond the control of the Ephoreia. The tombs have since been reburied and are no longer visible.

Another interesting artefact – to quote the excavation diary, ‘a marble fragment … that looks like a statue leg’ – was found in the disturbed soil from the dromos (Fig. 9). It is reported as 0.27 m long, but cannot now be located in the Ephorate's storerooms. Its discovery in this location is problematic unless we assume that the loose soil on the surface originated from other pits opened by the looters, who were very active and destructive throughout the cemetery.

Fig. 9. The excavation diary (left). The marble artefact as found during the excavation (right).

IV. CHAMBER TOMB 17. DROMOS – BURIAL I. SKELETAL ANALYSIS (BY OLIVIA A. JONES)Footnote 11

The skeletal remains excavated from the dromos burial of Tomb 17 in the Chalandritsa-Agios Vasileios cemetery were poorly preserved and heavily fragmented. The assemblage consisted of approximately 175 human bone fragments and 35 animal bone fragments. The animal remains consist of sheep/goat, hare and bird. Of the human material, the larger bone fragments (one third of the total) could be confidently identified. Apart from a whole right talus (foot bone), the remains were only small fragments; no bone fragment is larger than eight centimetres in length, width or diameter. Due to this high degree of fragmentation and poor preservation, an incomplete picture of the individual buried in the dromos must suffice. Fifteen human teeth in fair condition provide the bulk of data for interpreting this skeletal material.

The fragmentary nature of the human skeletal material prohibited any assessment of sexual traits and permitted only minimal studies of pathology. Estimation of age at death based on the post-cranial skeletal elements indicated that the individual was an adult due to the fused epiphyses. The dental material shows a moderate degree of attrition (tooth wear), indicating that the individual was an adult between 24 and 35 years old, according to Don Brothwell's dental ageing system (Hillson Reference Hillson1996, 240). The overall health of the individual is also shown in the dental remains: three cases of small and moderate caries, three cases of mild calculus, three cases of mild horizontal bone loss and three cases of enamel hypoplasia. The calculus, horizontal bone loss and caries show a normal amount of dental pathology for an adult during his/her lifetime. The enamel hypoplasia indicates that a certain degree of nutritional or pathological distress occurred during the formation of the tooth enamel when the individual was a small child. This osteological evidence shows that the individual buried within the dromos of Chamber Tomb 17 was an adult exhibiting normal health conditions, but the fragmentary nature of the material limits further study to microscopic and chemical analyses.

V. CHAMBER TOMB 17. DROMOS / BURIAL I – CATALOGUE OF FINDS

Sections V and VI present the catalogued pottery from the dromos and chamber of Tomb 17. See also sections XI and XII below for further parallels and discussions of shape and date.

-

1. T17 / Dromos / Π1 / AMP 16516 (Fig. 10) Kantharos, mended and restored in small parts of the rim, body, handle, and part of the base. Out-turned rim, making an angular junction with the shoulder; vertical strap handles with slightly concave back run from the lip to the maximum diameter of the belly. Gradual transition from upper to lower body. Flat base; slightly concave underside. Interior and exterior fully painted, except for the underside. Black to brownish-black paint, unevenly fired, faded and flaking in parts. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Height: 0.095 m, maximum diameter: 0.111 m, rim diameter: 0.092 m, base diameter: 0.05 m.

Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 114 no. 79, fig. 85.

-

2. Τ17 / Dromos / Π2 / ΑMP 16517 (Fig. 10)

Part of a skyphos, mended. Parts of the rim, the body and one handle preserved. Out-turned rim with a broad and flattened upper surface. Vertical sides on the upper body, tapering towards the missing base. Horizontal round handle on the shoulder. Fully painted interior, paint missing in parts. Small vertical lines on the horizontal surface of the rim, and a wide band below it. Reserved handle zone with traces of a horizontal wavy line (zigzag). Fully painted handles. Horizontal thin band runs below the reserved panel, followed by another wide band and a group of thin bands. Black-brownish paint, mostly faded and flaking. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.083 m, rim diameter (based on the drawing): 0.222 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 153, fig. 135στ.

-

3. Τ17 / Dromos / Π3 / ΑMP 16518. Not illustrated. Fragments of a handmade jug with fire marks most visible on the upper part. Coarse clay with many inclusions. Exterior surface smoothed with traces of slip. Straight, vertical sides; rim integrates with vertical neck, slight curve on the junction with the body. Side thickness: 0.005 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 113 no. 75, fig. 83; Dekoulakou Reference Dekoulakou1973, 15, fig. 1:1-I, pl. Iγ.

-

4. Τ17 / Dromos / Π4–Π5 /ΑMP 16534 (Fig. 11) Kantharos mended from several fragments; parts of the body and one handle restored in plaster. The base is not preserved. Thin, slightly out-turned rim; angular strap handles with slightly concave ridge; broad S-shaped body with very thin walls. Black painted ‘sausage’ motif in the top zone on both sides. Horizontal wavy line/zigzag in the reserved handle zone. Black paint over the rest of the exterior and interior. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Preserved height: 0.107 m, rim diameter: 0.104 m–0.093 m, maximum diameter: 0.115 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 284–5 no. 3, fig. 203, pl. 7.

-

5. Τ17 / Dromos / Π6 /AMP 16533 (Fig. 11)

Skyphos: sections of the rim, body and base restored in plaster. Out-turned rim with flat upper face; vertical shoulder and upper body, tapering from the horizontal round handles towards the flat base. Fully painted interior, small vertical lines on the horizontal surface of the rim; fully painted exterior except for the reserved handle zone containing a poorly executed horizontal wavy line/zigzag, mostly faded and difficult to identify. Matt brownish-black paint, faded and mostly flaking, perhaps due to firing conditions. The wavy line seems better executed on the other side of the vase, although not as well preserved. The upper part of the vase is warped due to poor control during shaping. Fabric 7.5ΥR 6/6. Height: 0.097 m, maximum diameter: 0.17 m, rim diameter: 0.183 m, base diameter: 0.078 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, fig. 135στ.

-

6. Τ17 / Dromos / Π7 /ΑMP 10612 (Fig. 12) Kantharos, partly preserved. One mended vertical strap handle, out-turned rim, S-shaped body and conical base. Matt black paint partly faded over the exterior and interior, except for a very thin reserved band at the lower edge of the foot and the base. Traces of a reserved panel in the handle zone. Fabric 7.5YR 7/6. Base diameter: 0.060 m, height (based on the drawing): 0.111 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Eder Reference Eder2001a, 43–4 no. 3, pls. 8:3, 12c:a; Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1986, 119–20 no. 1934, plan 11, pl. 38στ.

-

7. Τ17 / Dromos / AMP 17050 (Fig. 12) Conical base of a kantharos, similar to catalogue no. 8 (Fig. 12). Interior and exterior of lower body painted, with a reserved zone on the junction of the body and base and a black band around the lower edge of the foot. Fabric 7.5YR 6/6. Base diameter: 0.066 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1986, 119–20 no. 1934, plan 11, pl. 38στ.

-

8. Τ17 / Dromos – entrance-removal of blocking wall / ΑMP 10610 (Fig. 12) Kantharos partially restored in plaster (other fragments of the vase are not included in the restoration). Out-turned rim; vertical strap handle from the rim to just below the maximum diameter; S-shaped body of the broad type; conical base. Fully painted interior and exterior, reserved handle zone containing a horizontal wavy line/zigzag. Poorly executed reserved zone on the junction of body and base. Black paint, partly faded. Fabric 7.5ΥR 6/6. Height: 0.106 m, base diameter: 0.065 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1986, 119–20 no. 1934, plan 11, pl. 38στ; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 113 no. 73, fig. 83; Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 284–5 nos. 2, 4, figs. 202, 204, pl. 7.

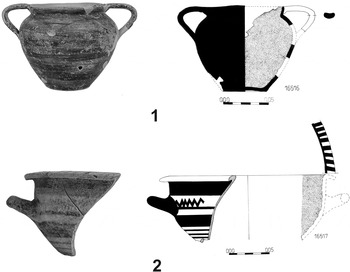

Fig. 10. Catalogue nos. 1–2.

Fig. 11. Catalogue nos. 4–5.

Fig. 12. Catalogue nos. 6–8.

VI. CHAMBER TOMB 17. CHAMBER FILL – CATALOGUE OF FINDS

Pottery groups from the chamber fill contained sherds of many different vessels, mainly kantharoi or skyphoi. Two body sherds with lustrous black paint and two rim and body sherds are similar to kantharos catalogue no. 4 (AMP 16534, Fig. 11): these were found in OM14 from excavation level one. Excavation level three (OM16) contained some black-painted sherds apparently from drinking vessels, and some rim fragments (including one decorated with small vertical lines). A selection of the most characteristic fragments found in the three levels (OM14, OM15 and OM16) is presented below.

-

9–12. T17 / Chamber / AMP 17007, 17008, 17009, 17010 (Fig. 13) Catalogue nos. 9 and 11 are thin-walled vessels while catalogue nos. 10 and 12 are thick-bodied vases. Their profile is either vertical or slightly curved, their interior unpainted and their exterior bears elaborate geometric decoration. Fabric 7.5ΥR 7/6. Maximum preserved height: 0.059 m (catalogue no. 9), 0.080 m (catalogue no. 10), 0.051 m (catalogue no. 11), 0.070 m (catalogue no. 12). Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–7 nos. 33, 36, 37, 38, 44, figs. 57, 60, 61, 62, 68.

-

13–14. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16519 a and 16519 b (Fig. 13) Sherds from the neck (13) and shoulder/body (14) of a large closed vessel with thick walls (possibly a large amphora). Unpainted interior; elaborately decorated exterior with horizontal bands and zigzags. Matt black, faded paint. Fabric 7.5ΥR 7/6. Maximum preserved height: 0.075 m (catalogue no. 13), 0.085 m (catalogue no. 14). Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–7 nos. 33, 36, 37, 38, 44, figs. 57, 60, 61, 62, 68.

-

15. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16520 (Fig. 13) Base and part of the lower body of a kantharos, restored (a few additional rim and belly fragments are not joined). Out-turned rim; round thin-walled body; low ring-base. Fully painted interior and exterior except for the rim and the underside of the base. Matt black, faded paint. Fabric 7.5ΥR 6/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.045 m, base diameter: 0.056 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 94 no. 9, fig. 39.

-

16. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16522 (Fig. 13) Part of the lower body and ring-base of an open vase. Fully painted interior; black band on the exterior at the junction of body and base. Matt brownish-black paint, faded. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.017 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 94–5 nos. 9, 11, figs. 39–40.

-

17–18. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16523, AMP 16524 (Fig. 13) Two parts of rim and upper body of drinking vessels, painted inside with a wide band on the junction of the rim and neck. Matt brownish-black paint, faded. Fabric grey (catalogue no. 17), 7.5YR 8/4 (catalogue no. 18). Maximum preserved height: 0.025 m (catalogue no. 17), 0.020 m (catalogue no. 18). Early Geometric? Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 153, fig. 135a.

-

19–20. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16525, 16526 (Fig. 13) Belly fragments of open thin-walled vessels: fully painted interior, horizontal bands on exterior. Brownish-black paint, faded. Fabric 7.5YR 8/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.053 m (catalogue no. 19), 0.054 m (catalogue no. 20). Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 122–5 (Troumbes, Chalandritsa).

-

21. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16527 (Fig. 13) Neck sherd of a thin-walled vase with a wide band on the interior and two bands on the exterior. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.043 m. Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 122–5 (Troumbes, Chalandritsa).

-

22. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16528 (Fig. 13) Two mended belly sections of a thin-walled drinking vase, fully painted on the interior and with three bands on the exterior. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.038 m. Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 122–5 (Troumbes, Chalandritsa).

-

23. T17 / Chamber / ΑMP 16529 (Fig. 13) Sherd of a thin-walled open vase, probably from the junction of rim and shoulder. Fully painted interior; radially arranged necklace on exterior. Fabric 7.5YR 8/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.030 m. Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 122–5 (Troumbes, Chalandritsa).

Fig. 13. Catalogue nos. 9–23.

VII. CHAMBER TOMB 17. POTTERY FROM THE NICHE

-

24. T17 / Niche / Π17 / ΑMP 14677 (Fig. 14) Small hydria with minor cracks on the body, one handle mended. Broad horizontal rim with inner rib; tall and wide cylindrical neck; one vertical grooved handle rising at the level of the rim to the lower shoulder; markedly curved transition from the shoulder to the roughly ovoid body. Two out-flaring horizontal roll handles are set at the point of maximum diameter (well above mid-body). Torus base. Wide band at the inner junction of rim and neck, one similar around the rim exterior; neck unpainted; painted vertical handle ridge; thin band around the junction of neck and shoulder with densely arranged long black tongues pendent from it; one pair of bands at the lower shoulder and a second around the belly below the handles; painted horizontal handle ridges; wide reserved zone on the lower body and a band around the junction with the base. Dark brown slip, black paint, faded and flaking in parts. Fabric 10YR 7/4. Height: 0.107 m, rim diameter: 0.056 m, maximum diameter: 0.078 m, base diameter: 0.043 m. Archaic. Cf. Caskey and Amandry Reference Caskey and Amandry1952, 197–9, pl. 55.

-

25. Τ17 / Niche / Π21 / ΑMP 16535 (Fig. 14) Oinochoe, restored: missing the handle, part of the rim, parts of the body and the whole base. Slightly out-turned rounded rim; tall wide neck; globular to ovoid body. Thin walls. The upper handle joint is visible on the rim. Band on the rim interior; exterior fully painted except for three narrow reserved bands at mid-neck and another group of five at the maximum diameter of the body. Matt black paint, faded and mostly flaking. Decoration hardly discernible due to uneven firing. Fabric 7.5YR 6/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.206 m, rim diameter: 0.104 m, maximum diameter: 0.203 m. Middle Geometric? Cf. Dekoulakou Reference Dekoulakou1982, 227, figs. 15–16; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 91 no. 2, figs. 35, 99–100 nos. 23–24, figs. 49–50.

-

26. Τ17 / Niche / Π22 / ΑMP 16536 (Fig. 14) The restored lower body and conical base of a closed vessel (oinochoe or lekythos). Unpainted interior; on the exterior a black painted band just above the maximum diameter, followed by a reserved zone with horizontal wavy line (zigzag) and a group of five bands beneath; junction of body and foot painted; unpainted underside. Matt brownish-black paint, faded and flaking. Fabric 7.5YR 6/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.065 m, base diameter: 0.057 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 94 no. 10, fig. 39.

-

27. T17 / Niche trench / AMP 16530 (Fig. 14) Six joined sherds from the neck and shoulder of an amphora with almost vertical walls. Signs of a black band on the rim interior. Poorly preserved decoration on the exterior, faded and flaking. Two horizontal black painted bands on the upper and lower neck flank the reserved panel, which contains a barely visible pictorial motif, part of which has flaked off. Vertical lines run down from the lower neck band towards the shoulder. Black paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.055 m. Late Geometric?

-

28. T17 / Niche trench / AMP 16531 a, b and c (Fig. 15) Three fragments of miniature vases. Their preservation does not permit secure attribution to a single vase. (a) part of the rim, shoulder and horizontal handle of a miniature skyphos; (b) part of the rim and shoulder and (c) a fragment probably from a conical base. All preserve signs of black paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.028 m (a), 0.022 m (b) and 0.015 m (c). Archaic. Cf. Payne Reference Payne1962, 290–1, 308–9, pl. 119; Pemberton Reference Pemberton1989, 169 no. 511, pl. 50.

-

29. T17 / Niche trench / AMP 16537 (Fig. 15) Fragment of miniature krater with an upturned horizontal roll handle in contact with the neck and rim. Signs of black paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.029 m. Archaic. Cf. Payne Reference Payne1962, 290–1, 308–9, pl. 119; Pemberton Reference Pemberton1989, 169 no. 511, pl. 50.

-

30. T17 / Niche trench / AMP 16538 (Fig. 15) Fragment of miniature vase, probably the base of a krater. No sign of paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.012 m, base diameter: 0.017 m. Archaic. Cf. Payne Reference Payne1962, 290–1, 308–9, pl. 119; Pemberton Reference Pemberton1989, 169 no. 511, pl. 50.

-

31. T17 / Niche trench / AMP 16539 (Fig. 15) Part of the lower body and base of a miniature krater or kantharos. A small plastic rib on the junction of the body and base; underside concave. Fully painted interior and exterior, including the underside. Black paint, faded and flaking. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.018 m, base diameter: 0.035 m. Archaic. Cf. Payne Reference Payne1962, 290–1, 308–9, pl. 119; Pemberton Reference Pemberton1989, 169 no. 511, pl. 50.

Fig. 14. Catalogue nos. 24–27.

Fig. 15. Catalogue nos. 28–31.

VIII. CHAMBER TOMB 24 (FIG. 16)

Rescue excavation was carried out in Tomb 24 in October 1991 following looting of the dromos (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1991, 147).Footnote 12 The disturbed deposit was first investigated, then the dromos fill in front of the facade was partially removed, and finally the chamber was excavated. No Geometric sherds were found in the dromos fill.

At the end of the dromos, the chamber entrance (0.65 m deep × 0.55 m wide × 0.83 m high) was found without a blocking wall.Footnote 13 Part of the chamber roof had collapsed, leaving a hole on the surface through which a metre of deposit had entered. Three excavation levels were removed: levels α΄ and β΄ (OM3 and OM4 respectively) were each approximately 0.25 m thick. Level α΄ consisted of deposits created by the hole in the chamber roof which post-dated the use of the tomb. A few black-painted Geometric sherds of open vases (OM3) plus bone fragments were found in this level. Level β΄ also seems to have been created by the hole in the roof, but the exact timing remains uncertain. The pottery (OM4) included various Mycenaean sherds, as well as Geometric sherds of black-painted vases. The disturbed burial stratum was found in the final 0.5–0.6 m-thick level γ΄ (OM5), where highly fragmented skeletal material and other finds were jammed among scattered stones (possibly belonging to the blocking wall). Along with the Mycenaean vases belonging to the burial stratum (which date to Late Helladic IIIA – Late Helladic IIIC middle), Geometric vases and sherds were also found, including kantharoi (catalogue nos. 44, Π1 / AMP 16540, 45, Π2 / AMP 16541, 46, Π3 / AΜP 16542, and 47, Π4 / AMP 16543).

IX. CHAMBER TOMB 24. SELECTED FRAGMENTS FROM LAYERS α΄, β΄ AND γ΄

A number of sherds and restored fragments, mainly from open vases, have been selected from those found in excavation levels α΄, β΄ and γ΄ (groups OM3, OM4 and OM5 respectively). Some have a greyish-brown fabric possibly due to firing conditions. Most characteristic are a conical base from a kantharos similar to catalogue nos. 7 and 8 (Fig. 12), a ring-base from a drinking vessel similar to catalogue no. 15 (Fig. 13) and a fragment of an oinochoe. Layer β΄ (ΟΜ4) included a small number of sherds of black (lustrous) painted vases, mainly of open shapes, some fully painted. The predominant fabric colour is 7.5YR 7/4. A selection of the most characteristic examples (from levels β΄ and γ΄) is presented below.

-

32. T24 / AMP 16544 (Fig. 17) Five joining fragments from the rim and body of a krater. Vertical lines on the upper surface of the outward rim, fully painted interior, on exterior two decorative zones with horizontal and vertical zigzags and metopes of vertical and oblique lines. Black faded paint. Clay colour: 10YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.110 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–12 nos. 33, 36, 38, 71, 72, figs. 57, 60, 62, 82; McDonald, Coulson and Rosser Reference McDonald, Coulson and Rosser1983, 258 P1617, pl. 3:73.

-

33. T24 / AMP 16545 (Fig. 17) Part of the belly of a vase with slightly curved walls, possibly an amphora. Unpainted interior. Three horizontal decorative zones with bands flanking a zigzag and vertical small lines. Black paint, faded and partly flaking. Fabric 7.5YR 8/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.113 m, width: 0.123 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–12 nos. 33, 36, 38, 71, 72, figs. 57, 60, 62, 82; McDonald, Coulson and Rosser Reference McDonald, Coulson and Rosser1983, 258 P1617, pl. 3:73.

-

34. T24 / AMP 16546 (Fig. 17) Belly fragment of an open vase with vertical walls, possibly from a krater. The interior painted black, on exterior a vertical zone flanking a vertical zigzag. Similar to catalogue no. 32. Clay colour: 7.5YR 6/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.039 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–12 nos. 33, 36, 38, 71, 72, figs. 57, 60, 62, 82; McDonald, Coulson and Rosser Reference McDonald, Coulson and Rosser1983, 258 P1617, pl. 3:73.

-

35. T24 / layer β΄ / AMP 16547 (Fig. 17) Belly fragment of a small thin-walled vase, possibly a small kantharos. Black-painted interior; on the exterior horizontal bands and a hatched triangle. Fabric 7.5YR 6/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.029 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 98 no. 19, fig. 46.

-

36. T24 / AMP 16548 (Fig. 17) Lower body and ring-base of a kantharos. Fully painted interior and exterior, except for the lower edge of the foot and the base. Thin walls. Lustrous black paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/6. Maximum preserved height: 0.029 m, base diameter: 0.058 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 94 no. 9, fig. 39. See also catalogue no. 15.

-

37. T24 / AMP 16549 (Fig. 17) Conical base of a kantharos, concave underside. Painted interior and exterior, reserved zone around the foot exterior. Black paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.027 m, base diameter: 0.059 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1986, 115 no. 1931, plan 8, pl. 38c. See also the base of the kantharos, catalogue no. 8.

-

38. T24 / ΑMP 16550 (Fig. 17) Part of the rim and upper body of an open vessel, possibly a skyphos. Out-turned rim with flattened upper surface decorated with vertical lines, rim perimeter painted. Reserved panel below the rim; the rest of the exterior and the interior fully painted. Lustrous black paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/3. Maximum preserved height: 0.040 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric.

-

39. T24 / AMP 16551 (Fig. 17) Part of the rim and shoulder of an open vase in a greyish-brown fabric. A black painted band covers the rim. Maximum preserved height: 0.035 m.

-

40. T24 / AMP 16553 (Fig. 17) Belly fragment of an open thick-walled vase. Painted interior; on the exterior, faded and partly flaking black paint, and traces of decoration with irregular curves. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.050 m.

-

41. T24 / AMP 16555 (Fig. 17) Belly fragment of a closed vase with vertical walls. Unpainted interior, exterior decorated with black bands. Fabric 7.5YR 7/6. Maximum preserved height: 0.028 m.

-

42. T24 / AMP 16556 (Fig. 17) Fragment of a skyphos, preserving parts of the rim, shoulder, body and root of the horizontal roll handle. Sharply down-turning rim decorated with small vertical lines. Fully painted interior; on the exterior, horizontal bands and circumscribed handle root. Black, faded and partly flaking paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.065 m. Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, fig. 135στ.

-

43. T24 / ΑMP 16557 (Fig. 17) Belly fragment of an open vessel. Signs of black paint on the interior; on the exterior, part of a leaf-shaped motif. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Maximum preserved height: 0.048 m.

Fig. 16. Ground plan and elevation of Tomb 24 (drawing: M. Philippopoulou-Petropoulou, 6th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, 1991).

Fig. 17. Catalogue nos. 32–43.

X. CHAMBER TOMB 24. THE FINDS FROM LAYER γ΄

-

44. Τ24 / Π1 / AMP 16540 (Fig. 18) Kantharos restored from sherds, missing most of one handle, part of the belly and part of the base. Rounded, slightly out-turned rim. Vertical strap handles from the rim to the maximum diameter; gradually curving transition from the upper to the lower body; thin walls and flat base. Fully painted interior and exterior, with only the interior of the handles and the underside of the base reserved. Black varied paint, faded and partly flaking. The vase is slightly misshapen, with an uneven base and oval rim due to poor potting. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4. Height: 0.090 m, belly diameter: 0.108 m, rim diameter: 0.082 m, base diameter: 0.059 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2007, 18–19, fig. 12; Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 290–1 no. 25, fig. 224.

-

45. Τ24 / Π2 / AMP 16541 (Fig. 18) Restored section of a kantharos preserving the base and half of the body. Similar to catalogue no. 44. Rounded, slightly out-turned rim; gradually curving transition from upper to lower body; flat base, slightly concave underside. Fully painted interior and exterior, apart from the reserved base. Black faded paint, partly flaking. Fabric 7.5YR 7/6. Height: 0.083 m, base diameter (based on the drawing): 0.055 m. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2007, 18–19, fig. 12; Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 290–1 nos. 22–5, figs. 221–4, pl. 9.

-

46. Τ24 / Π3 / AMP 16542 (Fig. 18) Part of open vessel, probably a kantharos, restored. Belly and most of the base preserved. Tall, flat base, slightly concave underneath. Fully painted interior and exterior. Black, mostly faded paint. Fabric 7.5YR 7/4, with small inclusions and greyish-brown patches caused in firing. Maximum preserved height: 0.048 m, base diameter: 0.053 m. Early Geometric?

-

47. Τ24 / Π4 / ΑMP 16543. Not illustrated. Fragment of a kantharos with partially preserved part of the rim, body and one handle. Rounded, slightly out-turned rim, gradual transition to the body. Vertical strap handle from the rim to the maximum diameter. Fully painted interior and exterior. Black-brownish paint, faded and partly flaking. Fabric 7.5YR 7/6. The fragment belongs to a kantharos similar to catalogue no. 44 and is not part of catalogue no. 45. Early Geometric. Cf. Gadolou Reference Gadolou2007, 18–19, fig. 12; Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 290–1 nos. 22–5, figs. 221–4, pl. 9.

Fig. 18. Catalogue nos. 44–46.

XI. THE POTTERY: FABRIC

A number of features of fabric common to both Mycenaean and Geometric pottery can be observed at Agios Vasileios. Most of the Mycenaean vases studied share a common fabric which lacks inclusions and falls around 7.5YR 7/4 and 7/6 on the Μunsell spectrum (Aktypi forthcoming a).Footnote 14 The pottery presented in this paper has a characteristic fine brown fabric, 7.5YR, with the majority of vessels ranging mainly between 7/4 (pink), 7/6 (reddish-yellow) and 8/4 (pink), followed by 6/4 (light brown) and 6/6 (reddish-yellow). Only the small hydria, catalogue no. 24 (Fig. 14), from the niche of Tomb 17, varies at 10YR 7/4 (very pale brown). Twenty of the 34 Geometric vases published by Gadolou (Reference Gadolou2008, 122–38) from the nearby Troumbes hill, Kamini and Katarraktis have a fabric in the 10YR range, between 8/4 and 7/4 (very pale brown), 7/6 and 8/6 (yellow) and 6/6 (brownish-yellow), while the remaining 14 belong in 7.5YR (ranging between 6/4, 6/6, 7/6 and 8/6).Footnote 15 In general, the slip on vessels from Agios Vasileios differs only slightly in colour from the body fabric; in fact, as Gadolou (Reference Gadolou2008, 291) remarks, it is simply a paler version. The surfaces of handmade vases (as catalogue no. 3) and certain cooking pot sherds from several groups and excavation levels are smoothed, with a very thin slip of a different colour discernible. Slip has not, therefore, been included in the vessel descriptions, with the exception of the small hydria, catalogue no. 24, where both fabric and slip colour are notably different. Paint is predominantly black or brownish-black and applied by brush (brush marks are evident in many cases, see e.g. the kantharos, catalogue no. 1 [Fig. 10]). The underside of the base usually remains unpainted. Variation in paint colour can be attributed to firing conditions (one should also note the thinness of the layer of paint usually applied), while the slightly twisted shape of a number of vases can be attributed to poor potting.Footnote 16 The most characteristic example is the skyphos, catalogue no. 5 (Fig. 11), which is obviously asymmetrical, where the paint is markedly inconsistent and the zigzag in the reserved panel also poorly executed.

XII. THE POTTERY: SHAPES AND CHRONOLOGY

Kantharos

The kantharos, catalogue no. 1 (Fig. 10), may be compared with the Early Geometric ΑMP 1061 from Priolithos, Kalavryta (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 114 no. 79, fig. 85). A further Early Geometric feature is the position of the maximum diameter of catalogue no. 1 above mid-height (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 291). Found together with catalogue nos. 2–7, catalogue no. 1 is conservatively dated to the Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric period on the following grounds.

Tomb 17 contains at least two examples of fully painted kantharoi with a horizontal zigzag in the reserved handle zone, a concave handle ridge and a conical base: catalogue no. 4 (Fig. 11), which also has a ‘sausage’ motif in the upper zone, and catalogue no. 8 (Fig. 12). Catalogue no. 6 (Fig. 12), which is similar in shape, may be a third example, but only traces of a reserved handle zone survive. Parallels from Achaea include examples from burial groups at Derveni (Vermeule Reference Vermeule1960, 16, pl. 5; Coldstream Reference Coldstream1968, 221, pl. 48c; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 151–5, fig. 135γ) and at 16 Kolokotroni Street in Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 113 no. 73, fig. 83). In Aetoloakarnania, two parallels come from Gavalou (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1986, 115 no. 1931, plan 8, pl. 38γ no. 1934, plan 11, pl. 38στ), three from Stamna (Christakopoulou-Somakou Reference Christakopoulou-Somakou2009, Τ55/19 [1998] 176, Τ122/4 [1999] 334, Τ150/4 [1999] 621) and four from Kalydon (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 283–4 nos. 1–3, 5, figs. 202–3, pl. 7:1–3). Further examples come from Ithaca (Souyoutzoglou-Haywood Reference Souyoutzoglou-Haywood1999, 110, pls. 31:S333, 37:S200a, 69:b, 71:a). All of these parallels are Late Protogeometric (early to middle ninth century bc). In her discussion of the Derveni burial, Gadolou comments that the horizontal zigzag in a reserved panel in the handle zone ‘…reflects one of the key elements of the transition of the Protogeometric to the Geometric period’ (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 152–5, 159, 284–8).

The kantharoi from Agios Vasileios, although close to the above parallels from Achaea (Derveni), Aetoloakarnania and Ithaca in both shape and decoration, present minor variations. Differences are most evident with published examples of the ‘tall type’, which has a strong vertical axis, out-turned rim and angular to almost biconical body (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 152; Christakopoulou-Somakou Reference Christakopoulou-Somakou2009, 1158–63). The recently published kantharoi from Kalydon with S-shaped body profile are defined as ‘broad type’ (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 293), and the kantharoi from Agios Vasileios seem also to belong to this type, having a softer outline (curved at the maximum diameter), lower conical base, thinner handles and delicate walls, while in general the overall shape appears lighter.Footnote 17 Kantharoi from Gavalou (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi1986, no. 1931) and Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, no. 73) are similar in size to catalogue no. 8 (0.105–0.109 m high – those from Stamna are 0.130–0.141 m high and those from Kalydon 0.120–0.159 m). The vases from Ithaca are smaller.

Catalogue no. 4 (Fig. 11), with a ‘sausage’ motif and horizontal zigzag in the handle zone, has a close parallel from Kalydon (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 284–5 no. 3 inv. 215, fig. 203, pl. 7) which is dated to the early ninth century, coincident with Coulson's Dark Age II period (975–850 bc) (McDonald, Coulson and Rosser Reference McDonald, Coulson and Rosser1983, 320; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 152). A trefoil-mouthed oinochoe from Kalydon (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 289 no. 18 inv. 210, fig. 217, pl. 8) has closely related decoration – a zigzag in a reserved band around the neck, four black discs on the shoulder forming a ‘sausage’ motif, and two overlapping discs around the root of the handle. The rare ‘sausage’ motif also appears on a few kantharos fragments from Ithaca (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1968, 227, pl. 49f; Souyoutzoglou-Haywood Reference Souyoutzoglou-Haywood1999, 114, pl. 37c,d), Palaiomanina (Mastrokostas Reference Mastrokostas1961–2b, no. 9, pl. 212a), and as early as Late Helladic IIIC late on the upper zone of a skyphos from Argos (Piteros Reference Piteros and Stampolidis2001, 113 AE 10043, fig. 39).Footnote 18 Finally, we note two unpublished kantharoi from Achaea of similar size, shape and decoration: a kantharos from a pithos burial at Drepanon,Footnote 19 and ΑMP 8465 from the Mycenaean tholos tomb at Kallithea (c.8 km north-north-west of Agios Vasileios), the base of which is fully restored (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1987, 69–72).Footnote 20 Presumably the base of catalogue no. 4 should be conical, like these examples. AMP 8465 was found in a similar context of reuse of a prominent tomb (the only tholos in a chamber tomb cemetery). The Kallithea tholos had been broken into via the west side of the vault and reused for multiple burials during the Protogeometric and later periods; in addition, a child burial without grave goods was found in the dromos. Parallels between the material from Kallithea and Agios Vasileios include, in addition to the two Protogeometric kantharoi, shared aspects of the fabric, decoration and local characteristics of the Mycenaean pottery.

Catalogue no. 6 (Fig. 12), while fragmentary, is an interesting shape that combines a straighter line in comparison with catalogue no. 8, and a higher conical base. It is similar to a Protogeometric kantharos from a pithos burial at Salmone in Elis (Eder Reference Eder2001a, 43–4 no. 3, pls. 8:3, 12c:a; Reference Eder and Mitsopoulou-Leon2001b, 233–43, pl. 6).

Catalogue nos. 44 and 45 (Fig. 18), and the fragmentary catalogue no. 47 from Tomb 24, have characteristic thin walls. Late Protogeometric parallels are four two-handled cups from Kalydon (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 290–1 nos. 22–5, figs. 221–4, pl. 9), and a kantharos from Derveni (Vermeule Reference Vermeule1960, 16–17, pl. 5, fig. 39 no. 55; Coldstream Reference Coldstream1968, pl. 48; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 153, fig. 135δ). Two Early Geometric kantharoi are also similar, one from Aegion (Dekoulakou Reference Dekoulakou1982, 224 no. 22, fig. 17; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 99, fig. 48) and the other from Trapeza near Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2007, 18–9 AMA 1874, fig. 12). These last two vessels are almost identical to catalogue no. 44 in shape, size and fabric colour (7.5 YR 7/6 as compared to 7.5 YR 7/4), while the remaining comparanda are smaller. Catalogue nos. 44 and 45 are paralleled in both shape and size by the Sub-Protogeometric kantharos 1976:5 from the Westhalle in the Agora of ancient Elis (Eder Reference Eder2001a, 38 no. 1, pls. 7b, 12c), as well as AMA 1841 from Erimo Chorio in the eastern Aegialeia (Kolia and Nestoridou Reference Kolia and Nestoridou1999–2001, 103–4), although the latter dates to the end of the Late Geometric period. The kantharos remained the most popular vase shape in Achaea throughout the Geometric period, evolving over time (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1968, 220–32; Reference Coldstream, Katsonopoulou, Soter and Schilardi1998, 325; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 291–6). However, the similarity of catalogue nos. 44 and 45 to the Late Protogeometric vessels from Kalydon (especially Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, no. 25) and the Early Geometric kantharos from Trapeza leads to a date just after Late Protogeometric, into the Early Geometric period.

Catalogue no. 46 (Fig. 18) has thicker walls and is larger than 44 and 45. A similar shape with a ‘raised’ base, which dates, however, to Late Geometric, is found in tombs in the Katarraktis region (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 136 no. 126, fig. 112). However, since catalogue nos. 44, 45 and 46 were found together, 46 should also date to the Early Geometric period.

Of the three ring-bases of kantharoi – catalogue nos. 15 (Fig. 13) and 16 (Fig. 13, possibly from a kantharos) from Tomb 17, and 36 (Fig. 17) from Tomb 24 – the first and third are of similarly fine quality with lustrous paint. Parallels are to be found at several sites, but the closest are the Early Geometric AMP 1195 and 1193 from Drepanon (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 94–5 nos. 9 and 11, figs. 39–40). AMP 1193 has a black band on the junction of body and base very close to that on catalogue no. 16. The Late Geometric AMA 840 from Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 102 no. 28, fig. 52) is similar, but its ring-base appears more developed.

Two conical kantharos bases are catalogued, with a third similar base found in the group of sherds from Tomb 24. Catalogue no. 7 (Fig. 12) from Tomb 17 and catalogue no. 37 (Fig. 17) from Tomb 24 are comparable to catalogue no. 8 and date to the Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric period.

Handmade jug

Handmade vases are known from tombs at several sites in Achaea (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 190–1). The coarse ware jug, catalogue no. 3 from Tomb 17, finds parallels in the Late Protogeometric jug AMA 1722 from Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 113 no. 75, fig. 83) and a jug from Drepanon (Dekoulakou Reference Dekoulakou1973, 15 no. 1, fig. 1:I, pl. Ι:γ). Three similar Protogeometric handmade jugs come from Kyparissia in Messenia (Chatzi-Spiliopoulou Reference Chatzi-Spiliopoulou1981–2, 321–47, figs. 13, 15), and a further late tenth-century parallel comes from the Makrygianni plot in Athens (Kalligas Reference Kalligas, Parlama and Stampolidis2003, 48, fig. 20; note his comments on the link between coarse ware jugs and Protogeometric women's tombs). Due to its fragmentary condition, catalogue no. 3 can only be dated on the basis of associated finds in Burial I, i.e. to the Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric period.

Skyphos

The skyphoi, catalogue nos. 2 (Fig. 10) and 5 (Fig. 11), from Tomb 17 follow the fashion for zigzag decoration in the handle zone of an otherwise monochrome vessel. Similar decoration appears on a skyphos from Derveni (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, fig. 135στ), although the shape differs (with a tall foot and raised handles), and the rims of the two skyphoi from Agios Vasileios are broad and decorated with short lines. Catalogue no. 2 is slightly larger than catalogue no. 5, and both are larger than the fragmentary catalogue no. 42 (Fig. 17) from Tomb 24. A horizontal handle in the sherd group from the chamber of Tomb 17 belongs to a fourth similar skyphos. All date to the Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric period.

Pottery from the niche of Tomb 17

The small hydria, catalogue no. 24 (Fig. 14), follows the general conventions of shape and decoration evident in the Archaic deposit at the Heraion of Argos: see especially the small hydria Caskey and Amandry Reference Caskey and Amandry1952, 197–9 no. 230, pl. 55. Although catalogue no. 24 has a roughly ovoid to almost biconical body, it is closely related in dimensions and outline. The numerous small hydriae found in Corinth differ in both shape and decoration (Blegen, Palmer and Young Reference Blegen, Palmer and Young1964, 172 no. 135–2, 187 no. 160–9, pls. 18:135–2, 24:160:9; Stillwell and Benson Reference Stillwell and Benson1984, 324 nos. 1872–9, pl. 70; Pemberton Reference Pemberton1989, 10–12, 168–9, pls. 18:164, 50:501, 505). This small hydria shape is closely related in form to the aryballos CP-2096 from the Lechaion cemetery (Amyx Reference Amyx1988, 25 with references, pl. 6:1a–e).Footnote 21 Catalogue no. 24 is well made and with minimalist decoration, giving it a simple yet elegant appearance. The dating of the parallels presented above ranges from the mid-seventh to the mid-sixth century bc, but on the basis of the closest parallel from the Argive Heraion, a date in the late seventh century bc is suggested.

Oinochoe

Catalogue no. 25 (Fig. 14) has a wide neck, globular body and characteristically thin walls. The exterior is monochrome, with groups of thin bands on the neck and at the maximum diameter. The paint is uneven and the decoration hardly discernible due to its firing. Parallels include the Early Geometric ΑΜΑ 525 and 515 from Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 99–100 nos. 23 and 24, figs. 49–50) and the Middle Geometric AMP 2010 from Ano Kastritsi (Dekoulakou Reference Dekoulakou1982, 227 no. 2, figs. 15, 16; Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 9, fig. 35). In Corinth, a similarly shaped globular oinochoe with a reserved neck panel filled with hatched meanders dates to the second half of the ninth century bc (Weinberg Reference Weinberg1943, 19 no. 69, pl. 11:69). Catalogue no. 25 is dated to the Middle Geometric period.

The lower part of the oinochoe or lekythos, catalogue no. 26 (Fig. 14), is similar to the oinochoe from the Derveni burial group (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 154, fig. 136θ), and to three vases from Kalydon (Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Stavropoulou-Gatsi, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 286–9 nos. 10, 12, 17, figs. 209, 211, 216, pl. 8:10,17). But it is best paralleled by the Early Geometric lekythos ΑMP 1140 from Drepanon (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 94 no. 10, fig. 39), which is richly decorated below the maximum diameter (the vases from Kalydon are fully painted). Catalogue no. 26 reflects a trend for decoration on a bright surface which develops through the Middle to Late Geometric (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 284–6). However, similarity to the Drepanon lekythos makes an Early Geometric date more likely.

Amphora

The decoration on the neck of catalogue no. 27 (Fig. 14) is too faded and flaking for any motif to be safely identified. What can be observed resembles part of an animal, possibly a horse head (or an attempt to depict one)Footnote 22 , but with insufficient detail to move beyond speculation. Pictorial motifs on the necks and shoulders of vases are well known in Late Geometric Achaea: three examples depicting three different types of animals have been found in the Chalandritsa area (two from Troumbes hill and one from Katarraktis) (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, nos. 102, 103, 109, figs. 96, 97 and 102).Footnote 23 Catalogue no. 27 is thus dated to the Late Geometric period.

Miniature vase

The miniature vases, catalogue nos. 28–31 (Fig. 15), belong to a long-lived tradition of sanctuary votives in the Aegean world. They are similar to published examples from Perachora (Payne Reference Payne1962, 290–1, 308–9, pl. 119) and Corinth (Pemberton Reference Pemberton1989, 169 no. 511, pl. 50). However, in western Achaea, over 21,000 votive miniature vases dating from the Geometric to the Hellenistic period are known from the rural sanctuary of Demeter Potiriophoros in Thea, not far from Agios Vasileios (Petropoulos and Rizakis Reference Petropoulos, Rizakis, Sklavenites and Staikos2005, 11–12),Footnote 24 and similar vessels have also been found at the sanctuary of Demeter Thesmophoros at Koupoulia, Petrochori further to the west (Petropoulos Reference Petropoulos, Leventi and Mitsopoulou2010, 164–6; Lakkaki-Marchetti Reference Lakkaki-Marchetti and Vlachopoulos2012, 353, fig. 713). There are also parallels from Kalydon in Aetolia, where a large number of Archaic miniatures were collected from deposits on the Acropolis (Bollen Reference Bollen, Dietz and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2011, 355–7, 455–518 nos. 280, 282, 284, 323, 324, figs. 256, 257). Based on these parallels, catalogue nos. 28–31 date to the Archaic period.

Fragments from Tomb 17

Catalogue nos. 9–14 (Fig. 13) mainly belong to large amphorae or oinochoae. Although their paint is poorly preserved, they were evidently richly decorated with horizontal and vertical zones of vertical small lines, hatched triangles and zigzags. This decoration resembles that of pottery from Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–7 nos. 33, 36, 37, 38, 44, figs. 57, 60, 61, 62, 68) and is characteristic of the Late Protogeometric and Early Geometric periods (see also on catalogue nos. 32–34 below).

The rim and belly sherds illustrated in Fig. 13 (catalogue nos. 17–18 and 19–23 respectively) are difficult to date exactly due to their fragmentary preservation and uncertain context. The rim sherds are similar to a kantharos rim from Derveni (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 153, fig. 135α). The belly sherds are all of high quality, with fine, thin walls. The horizontal black band decoration is found throughout the Geometric period, but in the region of Chalandritsa (at Troumbes and Katarraktis) it occurs on several vase shapes, mainly dated to Late Geometric (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 122–5). Catalogue nos. 17–18 are thus dated to the Early Geometric period and 19–23 more generally to the Geometric.

Fragments from Tomb 24

The krater and amphora sherds, catalogue nos. 32–34 (Fig. 17), are richly decorated in horizontal and vertical zones. They resemble Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric sherds from Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 105–12 nos. 33, 36, 38, 71, 72, figs. 57, 60, 62, 82) and Dark Age II sherds from Nichoria (McDonald, Coulson and Rosser Reference McDonald, Coulson and Rosser1983, 258 P1617, pl. 3:73). Further parallels are a kantharos from Derveni (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 155, fig. 135β) and two large kraters from Mesi Ayia, Patras, dated by Gadolou to the late ninth – early eighth century bc (Gadolou forthcoming). Gadolou (forthcoming) remarks that the sherds from Aegion, from smaller kraters, are an ancestral type and that the decoration, which continues throughout the Geometric period, develops and is enriched with further motifs on Late Geometric monumental vases.

Catalogue no. 35 (Fig. 17) is similar to the small Early Geometric kantharos AMA 186 from Aegion (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 98 no. 19, fig. 46).

Catalogue nos. 38–41 and 43 (Fig. 17), from various pottery groups, are fragmentary but of good quality and mostly with lustrous black paint. The rim, catalogue no. 38, is decorated with small vertical lines on the top surface, a motif used mainly on skyphoi and largely in the Late Protogeometric and Early Geometric periods (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 153, fig. 135στ). Catalogue nos. 39–41 and 43, however, can only be dated generally to the Geometric period.

XIII. CONCLUSIONS

The significance of the Geometric finds from the Chalandritsa region (Pharai) has been recognised by a number of scholars from Desborough (Reference Desborough1964, 97–101) and Coldstream (Reference Coldstream1968, 228–32; Reference Coldstream1977, 180) onwards. Most recently, Gadolou has studied the Geometric material culture and settlement of Achaea (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008; Reference Gadolou2012, 40–5), and the new evidence from Chalandritsa demonstrates all the features which she describes (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 323, 335). In terms of site location, the settlement and associated cemetery lie on low hills, overlook the gulf of Patras, have a ready outlet to the hinterland and are located near rivers and fertile valleys (the natural resources of which were exploited). Gadolou concludes that sites of this kind must have been small hamlets occupied by pastoralists, farmers and groups of potters. Chalandritsa probably played an important role in trade and communication, since it lay at a crossroads of a number of local and intra-regional routes to and from central Achaea, continuing a tradition that began in the Late Helladic period (Aktypi forthcoming b). In terms of material culture, in addition to shared ceramic traditions, the absence of metalwork among the Geometric finds at Agios Vasileios reflects wider Achaean practice. Gadolou (Reference Gadolou2008, 253) notes the virtual absence of metalwork (weapons in particular) in Achaean tombs, the exception being bronze rings from cist graves at Platanovrisi and Katarraktis (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 213, 250, 253). At Agios Vasileios, certain tiny bronze items found in levels which contained both Mycenaean and Geometric material should be considered Mycenaean rather than Geometric. They probably reflect later disturbance of Mycenaean deposits and the possible removal of bronze offerings.

The reuse of Mycenaean tombs has long been a matter of scholarly debate. Published lists of Mycenaean tombs with evidence of later intervention (Antonaccio Reference Antonaccio1995, with references) show that most examples come from the Peloponnese (the Argolid – Mycenae and Prosymna – and Messenia), with further cases e.g. in Boeotia, in Attica, on Kephallenia and on Crete. Examples within the ‘western koine’ are those excavated in Messenia by Choremis (Reference Choremis1973, 47; see also McDonald, Coulson and Rosser Reference McDonald, Coulson and Rosser1983, 266) and Chatzi-Spiliopoulou (Reference Chatzi-Spiliopoulou and Mitsopoulou-Leon2001, 293), whose work in the Mycenaean cemetery at Ellinika Antheias produced evidence for intervention during the Early Iron Age (Chamber Tomb 6). Many scholars have tried to analyse and explain the phenomenon as a whole, with varying results. Recent publications continue to present new cases of tomb reuse and ancestor worship at sites throughout the Aegean world, while discussion continues to highlight the considerations involved in different explanatory approaches.Footnote 25

As Mazarakis Ainian (Reference Μazarakis Ainian2000, 162) observes, Achaean burial customs in the Early Iron Age are similar to those of the Argolid and Corinthia, with inhumations in cists and, more rarely, pits, and the secondary use of Mycenaean tombs attested at Troumbes and Kallithea. Reuse of earlier cemeteries also occurred in other periods. At Kalamaki, Lousika, the entire area of the Early Helladic cemetery was reused during Late Helladic (Vasilogamvrou Reference Vasilogamvrou and Rizakis2000, 43–63); the case of the Kallithea tholos has already been noted; and Mycenaean Chamber Tomb 3 at Aegion (the roof of which had collapsed in antiquity) contained a Roman grave (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos1976, 6, pl. 17a–b). The small Late Geometric kantharos ΑΜΑ 453 was found inside a Mycenaean tomb on the Karogiannis plot in Aegion (Kallithea) (Gadolou Reference Gadolou2008, 102 no. 29, fig. 53); an Early Protogeometric cutaway neck jug with pointed base was found in the dromos fill of Chamber Tomb 19 at Voudeni (Kolonas Reference Kolonas1998, 225; Moschos Reference Moschos, Deger-Jalkotzy and Bächle2009, 252, fig. 9); and a similar Submycenaean jug was found in front of the entrance, and in contact with the facade of, Tomb 1 at Krini, Zoitada (Kaskantiri Reference Kaskantiri2012, 3).

The individual instances of later activity recognised in the Agios Vasileios cemetery present a diverse and complex picture. While some cases are straightforward to interpret, others remain problematic. This article has focused closely upon the descriptions given in the excavation diaries, in order to supply the fullest information for future study.

There are at least two cases of tomb reuse in the area of Chalandritsa. The first is at Troumbes, which lies on a low but imposing hill, overlooking the entire area including the neighbouring cemetery at Agios Vasileios.Footnote 26 It should, however, be noted that there is a lingering uncertainty about whether the structure concerned was indeed a tholos or some other type of construction. The second is Tomb 17 at Agios Vasileios, where the following individual episodes are observed.

-

a) Burial I: a single inhumation of an adult aged 24–35, with Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric offerings, in a pit in the dromos fill near the tomb facade, over a form of stone construction. This burial could be interpreted in terms of the community's attitude towards the sanctity of the location, and may also indicate the peaceful coexistence of ‘old’ and ‘new’ inhabitants. The deliberate choice of location may reflect the community's familiarity with its deceased ‘ancestors’ buried nearby in the cemetery. Given the morphology of the slope into which the Mycenaean chamber tombs were cut, it is probable that at least some of them remained visible during the period in question.Footnote 27

-

b) The presence of the Late Protogeometric – Early Geometric kantharos, catalogue no. 8, among the stones of the blocking wall remains difficult to interpret.

-

c) Geometric finds in the chamber fill can be interpreted either as later use of the chamber for one or more burials or as a disturbance above the Mycenaean burial stratum. Overlying (and thus later than) the latter, is the row of stones from the entrance to the back wall of the chamber, where the niche was found (and where the stones lay on top of each other). The stones seem to have been placed deliberately in order to cover the Mycenaean burial stratum.

-

d) Finds inside the chamber niche included both Mycenaean and Geometric pottery, and the same is true of the trench in the chamber floor. Excavation of the trench produced no evidence of solid bedrock, which may indicate that another entrance to the chamber of Tomb 17 was opened through a neighbouring chamber (17b) whose roof had collapsed. Where tombs are as densely arranged as they are at Agios Vasileios, it is not unusual for the walls of adjacent chambers to collapse, allowing direct access between them.Footnote 28 Since the excavation of the neighbouring Tomb 17b was never completed, this remains hypothetical. The Archaic pottery in the niche (the small hydria, catalogue no. 24, and the miniature vases, catalogue nos. 28–31) is of particular interest. Because of their size, small hydriae and other miniature vessels are interpreted as ritual/funerary offerings.Footnote 29 Their placement in the niche can thus be seen as a votive gesture. It should, however, be noted that the niche is not a closed context. Excavation, both from inside the chamber and down from the surface, produced pottery of different periods, and since the excavation was never completed, these results could not be fully investigated.

In the case of Tomb 24, the swift, rescue nature of the excavation meant that no stratigraphic study was made of the chamber, and the three excavation levels removed are hard to associate with archaeological strata. The tomb was probably reused or looted after its final Mycenaean use, resulting in disturbance of the burial stratum and its partial destruction when stones (probably from the blocking wall) were pushed inside the chamber. The discovery of a small bronze fragment in the burial stratum indicates the existence of at least one bronze artefact removed during the reuse or looting of the tomb. The pottery presented here was found in the upper part of the final excavation level (γ΄), and it is possible that the tomb was reused at this level in the Early Geometric period. All overlying fills probably entered through the partly collapsed chamber roof.

This article has presented the evidence for later activity in and around the Mycenaean tombs at Agios Vasileios in its wider regional context. It suggests that the Early Iron Age and Archaic population of Chalandritsa had ties with earlier inhabitants to the point that they felt it appropriate to venerate or honour them. The picture in Achaea echoes Papadimitriou's (Reference Papadimitriou, Deger-Jalkotzy and Lemos2006, 549) view of the Early Iron Age population of the Argolid ‘that they should not be necessarily considered as strangers and that they were finding opportunities to express their bonds with the past’. The pottery from Agios Vasileios indicates a Late Protogeometric and especially an Early Geometric phase of activity which partially bridges the gap in habitation that most scholars have acknowledged in the region. If such a gap did exist in the Chalandritsa (Pharai) area, it must have been short. Lemos (Reference Lemos2002, 195) remarks that, whereas in Laconia there is a lack of archaeological material between the Late Helladic IIIC and the Protogeometric period, in Messenia the chronological gap is smaller because of the greater number of finds. The situation in Achaea is still unclear, because the gradual publication of old finds is now enabling old questions to be addressed anew. Study of the Mycenaean cemetery at Agios Vasileios and of the neighbouring Mycenaean settlement at Stavros, combined with extensive research now being carried out in western Achaea, will soon provide new data with which to resolve the issue of continuity of settlement in the region.