INTRODUCTION

The chronological synchronisation between Late Minoan/Late Helladic IIIA1 and the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III has been well known since the finding of a scarab bearing his name in Tomb 4 at Sellopoulo near Knossos together with Late Minoan IIIA1 pottery and a Late Helladic IIIA1 jug (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974).

However, that this is ‘one of the best Aegean–Egyptian synchronisms’ (Warren and Hankey Reference Warren and Hankey1989, 148)Footnote 1 has recently been challenged as part of the ongoing controversy about the radiocarbon absolute dating of the Minoan Thera eruption and its implications for the conventional archaeological–historical chronology of the Aegean (Manning Reference Manning1999, 220–2).Footnote 2 The attempt to disassociate Late Minoan IIIA1 from Amenhotep III so as to allow an earlier date for this period plays down the importance of the scarab from Sellopoulo by suggesting that it was old at the time of its deposition, and, worse, that it was not a product of Amenhotep III's workshops and may have been produced after his reign (Manning Reference Manning1999, 222).Footnote 3

In the present article we introduce new data that corroborate the chronological synchronisation between Amenhotep III and Late Minoan IIIA1, at least until the last decade of Amenhotep III's reign. First, we present a recent find of an Amenhotep III scarab discovered together with two rare Late Minoan IIIA1 cups in the destruction layer of an early Late Bronze Age IIA (first half of the fourteenth century bc) public building currently under excavation at Tel Beth-Shemesh, Israel (for the cups and their Knossian comparanda see Bunimovitz, Lederman and Hatzaki Reference Bunimovitz, Lederman and Hatzaki2013).Footnote 4 The scarab is interpreted as a commemorative scarab produced on the occasion of Amenhotep III's celebration of his first Jubilee or Sed festival. Second, in light of this reading of the new Beth-Shemesh scarab we re-examine the scarab from Sellopoulo Tomb 4 and suggest that it too relates to Amenhotep III's first Sed festival. We then discuss the important implications of the new information and observations on Aegean chronology.

THE NEW AMENHOTEP III SCARAB FROM TEL BETH-SHEMESH

Archaeological context

In the companion article (Bunimovitz, Lederman and Hatzaki Reference Bunimovitz, Lederman and Hatzaki2013), the circumstances of the recent discovery at Tel Beth-Shemesh of two Late Minoan IIIA1 cups and an Amenhotep III scarab in the same context are fully detailed. We therefore recount here only the main contextual and stratigraphic information.

The main architectural complex exposed in Level 9 (late Bronze IIA – fourteenth century bc) of the current excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh is a large edifice – a ‘palace’, due to its size, construction and rich contents. The ‘palace’ was discovered completely destroyed and sealed under a mantle of fallen mud bricks fired by a heavy conflagration. It is in one of this building's rooms (L1556/1530) that the scarab of Amenhotep III (Reg. No. 5901.03) was found, next to a large assemblage of pottery and a variety of other artefacts. The pottery assemblage and the two Late Minoan IIIA1 cups seem to have comprised feasting paraphernalia stored together. A group of handmade human and animal figurines found among the feasting vessels hints at the ceremonial/ritualistic context of the feast.

Other notable finds from the room (Fig. 1) are a unique plaque figurine, presumably of a female ruler presented as a male (Ziffer, Bunimovitz and Lederman Reference Ziffer, Bunimovitz and Lederman2009), and three bronze arrowheads that may attest the violent circumstances in which the ‘palace’ came to its end.

Fig. 1. Finds from context L1530 at Tel Beth-Shemesh: Scarab 5901.03, plaque figurine, Cypriot Base Ring I juglet, three bronze arrowheads and a bronze drinking-straw tip.

The pottery assemblage contextually related to the Amenhotep III scarab and the Late Minoan IIIA1 cups is but part of a larger pottery collection exposed all over the ‘palace’ under its destruction debris. The study of this assemblage, which includes dozens of local vessels accompanied by some Cypriot imported ware (Base Ring I juglets and White Slip II bowls), shows that it spans the Late Bronze IB–IIA period, namely, the late fifteenth and first half of the fourteenth century bc. This dating is corroborated by the reading and interpretation of the Amenhotep III scarab discussed below.

Description and analysis

Scarab: Reg. No. 5901.03, Area A, Square B22, Layer 1530 (Fig. 2).Footnote 5

Fig. 2. Scarab 5901.03 from Tel Beth-Shemesh: photographs, drawings and reconstructions.

Material: Glazed steatite,Footnote 6 traces of green glaze on the base and the right side (Fig. 2 a, e); the rest has faded into ivory-white (cf. Keel Reference Keel1995, 153 §406).

Dimensions: Length 43.5 mm, width 31 mm, height 9.75+ mm (estimated 22 mm).

Method of manufacture: Carving, abrading, drilling, incising and glazing.

Workmanship: Excellent.

Technical details: Perforated, drilled from both sides (Fig. 2.3 and c). Linear and hollowed-out engraving with hatching (Fig. 2.1 and a ).

Preservation: Broken through the perforation; the entire back, i.e. the upper half, is missing (Fig. 2.2–6 and b–f ).

Scarab shape: Since the entire upper half of the scarab is missing there is no justification for referring to any typology relating to New Kingdom scarab shape details.Footnote 7 However, a reconstruction of the four sides of the scarab is given as a visual guide to its overall shape (Fig. 2.2, 2.4–6).

Base design: Within a horizontal oval (that served as a frame) is depicted on the right an Egyptian vertical cartouche containing a royal name, with additional hieroglyphic signs that are usually identified as an epithet: Nb-mAat-Ra mrj Jmn-Ra = ‘Neb-Maat-Ra [the prenomen (Throne Name) of Amenhotep III] beloved of [the god] Amun-Re’ (Fig. 2.1 and 2 a , Fig. 3.1).

Fig. 3. Parallels for the formula appearing on the Tel Beth-Shemesh scarab. 2: Macalister Reference Macalister1912, vol. III, pl. 205 a 12 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 288–9, no. 274; 3: Hornung and Staehelin Reference Hornung and Staehelin1976, 261 no. 350; 4: Hall Reference Hall1913, 180 no. 1792; 5: Petrie Reference Petrie1932, pl. 8.128 = Keel Reference Keel1997, 214–15 no. 331.

Excavated and provenanced scarabs with the same formula are known from Gezer (Macalister Reference Macalister1905, 188 no. 13, 189 pl. 1.12 = 1912 vol. II, 321 no. 194; 1912 vol. III, pl. 205a.12) (Fig. 3.2) and Tell Basta (Hornung and Staehelin Reference Hornung and Staehelin1976, 261 no. 350, pl. 36.350) (Fig. 3.3), while a vertical variant with additional hieroglyphic signs (phonetic complement) was excavated at Tell el-Ajjul (Keel Reference Keel1997, 214–5 no. 331 with earlier bibliography) (Fig. 3.5). A very close, but unprovenanced, parallel – where the only difference is the opposite direction of the lexeme mrj – is kept in the British Museum (Hall Reference Hall1913, 180 no. 1792) (Fig. 3.4).

Typology: According to conventional typology the scarab would have been attributed to the category ‘scarabs that bear royal names’; see, however, the discussion below.

Origin: Egyptian product, imported to Canaan.

Date: The scarab should be dated to the ruling years of Amenhotep III, 1391–1353 bc (Kitchen Reference Kitchen and Åstrom1987; Reference Kitchen and Åstrom1989), 1390–1353 bc (Hornung, Krauss and Warburton Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006, 492).

SEARCHING FOR INNER CHRONOLOGY AMONG AMENHOTEP III SCARABS

The usual time span given to scarabs bearing the names of Amenhotep III or his Great Royal Wife Tiye are the entire 38 regnal years of the pharaoh.Footnote 8 This time span is quite long and one would like to refine the inner chronology of these scarabs.

The size, the inner design and the nature of the formula of the new Beth-Shemesh scarab enable us to pursue further its analysis with the aim of establishing a more precise date for its manufacture. Eventually, this analysis led us to re-investigate the Amenhotep III scarab from Sellopoulo, with illuminating results.

Large commemorative scarabs (LCS)

Since there were no changes in Amenhotep III's nomen or prenomen (Beckerath Reference von Beckerath1999, 140–3),Footnote 9 the only effort to find chronological criteria for dating his scarabs has concentrated on the series of Large Commemorative Scarabs (with length range between 52 and 110 mm), since many of them bear reference to some of the pharaoh's regnal years (Blankenberg-Van Delden Reference Blankenberg-Van Delden1969, 4). The scarabs are usually divided into five types:Footnote 10

-

Type A – ‘Marriage’/Boundaries scarabs. Although lacking any regnal year, these scarabs have been ‘pushed’ into Regnal Year 1 or the very beginning of Regnal Year 2, since Tiye – the ‘Great King's Wife’ – is mentioned with this title already on Type B scarabs (Blankenberg-Van Delden Reference Blankenberg-Van Delden1969, 4–5).

-

Type B – Wild bull-hunt scarabs = Regnal Year 2.

-

Type C – Lion-hunt scarabs = Regnal Year 1 to Regnal Year 10, i.e. the first 10 years.

-

Type D – Gilukhepa/Kirgipa scarabs = Regnal Year 10.

-

Type E – Irrigation Basin/Lake scarabs = Regnal Year 11.

Table 1. Excavated and some only provenanced* large commemorative scarabs of Amenhotep III. Blankenberg-Van Delden Reference Blankenberg-Van Delden1969, 194–5 [D. Concordance of Provenance]. Additional items: A: Meroe – Török Reference Török1997, 235 inscription 4, fig. 118 inscription 4; C: Jaffa – Sweeney Reference Sweeney2003, 54–9, fig. 1; C: Qal'at et-Twal (Petra) – Ward Reference Ward1973; C: Palaepaphos-Skales – Clerc Reference Clerc and Karageorghis1983, 389–92, fig. 7, pl. 190.17; D. Beth Shean – Goldwasser Reference Goldwasser2002; 2009 = Keel Reference Keel2010, 202–3 no. 234.

This scheme is based on the assumption that each type of the LCS was produced separately and in a chronological order – following the regnal years of Amenhotep III. However, that assumption was challenged by Lawrence M. Berman with the claim that technically speaking it seems that all the LCS were produced in one workshop and at the same time, ‘sometime, then, in the eleventh year of his [Amenhotep III's] rule or thereafter’ (Berman Reference Berman, Kozloff and Bryan1992, 68).

We will later refer to this suggestion, which still stands on a maximal time span of 28 years for the LCS group, between Regnal Years 11 and 38. Here, we just want to note that ‘Type A’ scarabs could not be dated to Regnal Year 1 since there are too many scarabs – of lesser sizes (Fig. 4.4–7 and Fig. 5.4–6) – where Tiye appears only as ‘King's Wife’,Footnote 11 i.e. she received the title ‘Great King's Wife’ after some time, perhaps after having a son that seemed to fit the status of an heir to the throne. A date before Regnal Year 10, i.e. before Amenhotep III's marriage with Gilukhepa/Kirgipa (Type D), has been suggested by Gundlach (Reference Gundlach and Schmitz2002, 33 and 45).

Fig. 4. Medium-size commemorative scarabs Type A: royal colossi of Amenhotep III and Tiye. 1: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 190 no. 485; 2: Wiese Reference Wiese1990, 31 ill. 54; 3: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 190 no. 486; 4: Petrie Reference Petrie1889, pl. 42.1309; 5: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 190 no. 489; 6. Petrie Reference Petrie1889, pl. 42.1305; 7: Newberry Reference Newberry1906, pl. 30.28; 8: Petrie Reference Petrie1889, pl. 42.1308; 9: Pier Reference Pier1906, pl. 19.148; 10: Vincent Reference Vincent1903, 606 no. 5 = Keel Reference Keel1997, 690–1 no. 5.

Fig. 5. Medium-size commemorative scarabs Type B: cartouches of Amenhotep III/Tiye. 1: Macalister Reference Macalister1912, vol. III, pl. 207.31 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 330–1 no. 376; 1a: Petrie Reference Petrie1889, pl. 41.1267; 2: Murray Reference Murray and Tufnell1953, pl. 45.156; 3: Macalister Reference Macalister1912, vol. II, 320 no. 184, fig. 454 [top] = Keel Reference Keel2013, 186–7 no. 46; 4: Petrie Reference Petrie1932, pl. 8.127 = Keel Reference Keel1997, 214–15 no. 330; 5: Dunand Reference Dunand1950, pl. 197.13411; 6: Nunn Reference Nunn1999, 100–1 no. 252; 7: Petrie, Wainwright and Mackay Reference Petrie, Wainwright and Mackay1912, pl. 50.31.

Additional series of commemorative scarabs of Amenhotep III

Two more series – or groups – of commemorative scarabs were identified among those related to Amenhotep III and his ‘Great King's Wife’, Tiye. According to Ludwig Keimer (Reference Keimer1939, 117) these are ‘minor historical scarabs’ – of regular size, and ‘medium sized historical scarabs’ – of a length between 40 and 55 mm.

This division relies on the identification of some regular-sized scarabs of the earlier rulers of the 18th Dynasty (Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV) as commemorative, or as ‘minor historical scarabs’ (Keimer Reference Keimer1939, 112–17).Footnote 12

In spite of the extension of the use of the term ‘commemorative scarabs’ to scarabs of reduced size and no regnal years, none of these has been related to a specific date. Moreover, many such scarabs are often overlooked, or merely identified as bearing a royal name with an additional epithet. As we will show below, medium-size commemorative scarabs of Amenhotep III and Tiye can be categorised into certain series or types and – even more importantly – these series or types can be dated.

Categorising the medium-size commemorative scarabs (MSCS)

Keimer's definition of the medium-size commemorative scarabs can be elaborated on two aspects: the size range and the inner design.

The size of many such scarabs is less than 40 mm (especially of the ‘faience group’ – MSCS Type D – to be discussed below); it is therefore suggested to extend the size span of the MSCS into between 34 and 55 mm.

The inner design of the MSCS – supposedly restricted to a cartouche with the prenomen and an epithet (Jaeger Reference Jaeger1982, 139–42 ills. 368–85, 142–44 ills. 387–97) – should be considered much more varied and richer, as apparent from additional designs and formulae identified and discussed below. These are the key for subdividing the MSCS mentioned in this work into three categories or types (A–C). An additional type is the ‘faience group’ (Type D), where the prenomen appears without a cartouche.

1. Medium-size commemorative scarabs – Type A: royal colossi of Amenhotep III and Tiye (Fig. 4)

The groundbreaking type is a neglected group of scarabs that show different royal statues: of the king alone, with his famous consort, and even of her alone – but always followed by cartouches with their names (Fig. 4.1–3, 4–7 and 8–10 – respectively).Footnote 13 In most cases when Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye appear alone they are sitting on a throne. This new phenomenon on scarabs follows earlier visual descriptions of raised pairs of obelisks depicted on the scarabs of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III and Amenhotep II (Hari Reference Hari1974, figs. 11–13).

Such a development leads us to the interpretation that this group commemorated a small number of statues of colossal size – or colossi. Most of these colossi stood in the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III at Kom el-Hetan, Thebes West.Footnote 14 Later, during Ramesses II's period, scarabs describing his own colossal statues were issued following those of Amenhotep III (Hall Reference Hall1913, no. 2225; Yoyotte Reference Yoyotte1949, 87 no. 17; Wiese Reference Wiese1990, 38 fig. 61, cf. p. 30).

2. Medium-size commemorative scarabs – Type B: cartouches of Amenhotep III/Tiye (Fig. 5)

This type includes scarabs bearing one cartoucheFootnote 15 (Fig. 5.1 from Gezer) or both cartouches of Amenhotep III (Fig. 5.2 from Lachish), scarabs bearing his and Tiye's cartouches together (Fig. 5.3–6 from Gezer, Tell el-Ajjul, Byblos and Ras-Shamra/Ugarit, respectively), and even scarabs with only the cartouche of Tiye (Fig. 5.7 from Mazghuneh, Egypt) – all of them without any graphical addition.

Since the previous group of MSCS (Type A) already contains the cartouches of Amenhotep III and his Royal Wife Tiye depicted in relation to their sculptured images, the appearance of their cartouches without adjacent images demands a different explanation.

The scarabs found in Canaan may be compared with the Brick Stamps found at Malkata, the compound built near Kom el-Hetan for the stay of Amenhotep III and his entourage in Thebes West while participating in his Jubilees (see Kemp Reference Kemp1989, 203 fig. 71, 213–17). There, the bricks stamped with both cartouches of Amenhotep III were found exclusively in the ‘Palace of the King’ (Fig. 6.I–II), while those stamped with cartouches of the king and his wife were found exclusively in the ‘South Palace’ – the palace of Tiye (Fig. 6.III–IV). It seems, therefore, that five of the scarabs in the group under discussion commemorate two defined palaces at Malkata that were also connected to the Jubilee. The first Gezer scarab (Fig. 5.1) and the scarab from Mazghuneh, Egypt (Fig. 5.7) may refer to buildings at other sites.

Fig. 6. The association of stamped bricks with various buildings at Malkata. Hayes Reference Hayes1951, figs. 1, 30 I–X.

3. Medium-size commemorative scarabs – Type C: cartouche of Amenhotep III prenomen and an epithet

The general definition of the original type of medium-size commemorative scarab follows a large number of regular-size scarabs. It was related to scarabs with Amenhotep III's prenomen depicted in cartouche, accompanied by a few hieroglyphs that have been generally identified as epithets.

Such combinations – where the cartouche is perpendicular to the scarab's orientation and is located on one of its edges – were invented already during the reign of Thutmose I, but their number increased dramatically during the reign of Amenhotep III.Footnote 16

The main problem is the identification of the epithets. Some of those may refer to boat names (see below), others to various architectural elements such as small sanctuaries, pylons, naoi, obelisks etc.

One subgroup among these scarabs that contains more than a dozen variants deserves special attention. In this subgroup – to which the Beth-Shemesh scarab also belongs – the lexeme mrj ‘beloved by’ always appears, together with a name of a deity, i.e. ‘Amenhotep III beloved by [god's or goddess's name]’.Footnote 17 Since these formulae did not appear among the regular titular of Amenhotep III (Beckerath Reference von Beckerath1999, 140–3), they require a different explanation.

The enigma of the special formulae is solved by referring to an additional group of sculptures, not of the royal colossi, but of a variety of deities. Each such sculpture bears – on top of its base and near the deity's feet – the sculpture's name within a framed rectangle (Fig. 7.1 a, 7.2 a ). In this group the name of the deity is related to the first Jubilee or Sed festival (Bryan Reference Bryan and Quirke1997, 57–8), together with both the cartouches of Amenhotep III and the lexeme mrj (beloved) (Bryan Reference Bryan and Quirke1997, pls. 10 c, 14, 15 a–b, 20 a, 22 a, 29 c). In other words, the complete names of these sculptures do not refer directly to the deities they represent. The names are composed into the formula: ‘Amenhotep III, beloved of [god or goddess related to the Jubilee or the Sed festival of the pharaoh]’.

Fig. 7. Medium-size commemorative scarabs Type C: cartouche of Amenhotep. III with the prenomen and the epithet ‘beloved’ by a god or goddess as a shortening of sculpture's name. 1: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 188 no. 455; 1a: Bryan Reference Bryan and Quirke1997, pl. 29 c; 2: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 188 no. 454; 2a: Bryan Reference Bryan and Quirke1997, pl. 15 b.

All these sculptures originated in the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III at Kom el-Hetan, in Thebes West, but later some were transferred to other sites and even usurped by later pharaohs.

This exceptional complex, megalomaniac in its size, which contained more than a thousand sculptures made of four different stones, and which seems to present a sky map of the entire universe (Bryan Reference Bryan and Quirke1997), was designed on purpose to overshadow the famous nearby mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri.

We suggest that the formulae on Amenhotep III scarabs containing the lexeme mrj should be understood as shortenings of the larger texts incised on some of the divine sculptures' bases. The scarabs bearing the epithets ‘Amenhotep III, beloved of Bastet’ (Fig. 7.1) or ‘… of Weret-Hekau’ (Fig. 7.2) seem each to commemorate an individual surviving statue (shown beneath them – Fig. 7.1 a, 7.2 a ). Moreover, since all these sculptures were related directly to the first Jubilee of Amenhotep III, the same could be said about the scarabs.

This deduction means that the production date of these scarabs (Type C), as well as of the scarabs depicting colossi (Type A) and those commemorating a certain palace at Malkata (Type B), is close to the first Sed festival (the Jubilee held during Regnal Year 30) – a few years before or after that event – i.e. between Regnal Year 28 (since the statues and palaces were finished before the celebrations) and Regnal Year 34 (which is already the date of the second Jubilee).

A similar connection to Sed festivals has been ascribed to scarabs of Thutmose III commemorating the raising of obelisks (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2008, 41 no. 45). Additional support may be also found in the fact that only one fragment of a scarab of Type C (a subgroup not discussed here) was found at Tell el Amarna (Petrie Reference Petrie1894, 28 §65, pl. 14.7).Footnote 18

4. Medium-size commemorative scarabs – Type D: ‘faience group’ with Amenhotep III prenomen (Fig. 8)

While the three types of commemorative scarabs (Types A–C) previously discussed were all made of glazed steatite, the fourth type is made exclusively of faience. Most of these scarabs contain only the prenomen of Amenhotep III, depicted freely without any cartouche.Footnote 19 In a very few cases, a different variant of the prenomen (Nb-MAat-Ra) was used (Nb-MAat-Ra tjt-Ra Footnote 20 and Nb-MAat-Ra mrj.[n]-Ra) (Beckerath Reference von Beckerath1999, 142–3 T5 and T11; see Fig. 8.2–3, 8.5 and Table 2, respectively).

Fig. 8. Excavated medium-size commemorative scarabs Type D: faience group with Amenhotep III prenomen. 1: Petrie Reference Petrie1932, pl. 8.126 = Keel Reference Keel1997, 214–5 no. 329; 2: James Reference James1966, fig. 100.15 = Keel Reference Keel2010, 122–3 no. 55; 3: Loud Reference Loud1948, pl. 153.224; 4: Macalister Reference Macalister1912, vol. III, pl. 202 b 1 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 238–9 no. 159; 5a: Cline Reference Cline1987, pl. 4.10; 5b: Keel and Kavoulaki Reference Keel, Kavoulaki, Karetsou, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Papandakis2001, 320 no. 329.

Table 2. Excavated medium-size [length 34–40 mm] faience commemorative scarabs (MSCS) of Amenhotep III in relation to large commemorative scarabs (LCS).

Vertical: Gurob – Petrie Reference Petrie1891, pl. 22.17; Kahun – Petrie Reference Petrie1891, pl. 8.22; Malkata – Hayes Reference Hayes1951, fig. 31 R28; Dakka – Firth Reference Firth1915, pl. 41.3; Tell Abu Hawam – Keel Reference Keel1997, 10–13 nos. 17–18 – with previous bibliography; Aphek – Giveon Reference Giveon1988, no. 50 = Keel Reference Keel1997, 88–9 no. 27; Tell el-Ajjul – Keel Reference Keel1997, nos. 270, 329, 432, 445, 555 – with previous bibliography; Ashkelon – Keel Reference Keel1997, 696–7 no. 22; Beth Shean – James Reference James1966, 316, fig. 100.15 = Keel Reference Keel2010, 122–3 no. 55; Gezer – Macalister Reference Macalister1912, vol. III, pl. 207.39 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 334–5 no. 385; Hazor – Yadin et al. Reference Yadin, Aharoni, Dunayevsky, Dothan and Dothan1961, pl. 283.2; 1989, 341 H 124/1 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 610–11 no. 64; Jaffa – Sweeney Reference Sweeney2003, 59–60, figs. 2–3; Lachish – Tufnell, Inge and Harding Reference Tufnell, Inge and Harding1940, pl. 32.37; Megiddo – Loud Reference Loud1948, pl. 153.224; Tell es-Safi – Giveon 1978, 99–100, fig. 50 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 108–9 no. 32; Byblos – Dunand Reference Dunand1950, pl. 201.9896; 1954, 323 no. 9896; Ialysos (Rhodes) – Cline Reference Cline1987, pl. 4 fig. 11; 1994, pl. 4.12.

Horizontal: Malkata – Hayes Reference Hayes1951, fig. 31 R31,R32; Gezer – Macalister Reference Macalister1912, vol. III, pl. 202 b 1 = Keel Reference Keel2013, 238–9 no. 159; Hazor – Keel Reference Keel2013, 616–7 no. 78: Lachish – Tufnell, Inge and Harding Reference Tufnell, Inge and Harding1940, pl. 32.36,38; Khania/Kydonia – Cline Reference Cline1987, pl. 4 fig. 10; Keel and Kavoulaki Reference Keel, Kavoulaki, Karetsou, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Papandakis2001, 320 no. 329.

At this stage, no specific candidate for the commemoration by the faience scarabs is suggested.

The importance of the faience MSCS (Type D) can be deduced from their distribution in Egypt itself. There, these scarabs were excavated in the palatial complexes of Amenhotep III at Gurob and Malkata (for the significance of their material see further below).

This group of MSCS is the most common in the eastern Mediterranean. In Greater Canaan (which includes Transjordan and the Phoenician coast) (Table 2 – ‘Canaan’) 21 scarabs were found at 12 sites (for some of these, see Fig. 8.1–4). Five of these sites acted as harbours.Footnote 21 At some of the sites both MSCS and LCS were found. Moreover, some of the sites are linked to the Egyptian correspondence with their vassals, as revealed through the Amarna tablets/letters (Moran Reference Moran1992: xxvi–xxxiii) (Table 3 – ‘Canaan’).

Table 3. Excavated MSCS, RSCS and LCS in relation to el Amarna letters (EA) and Kom el-Hetan Aegean List (KeH). MSCS D Faience – see Table 2; MSCS B Cartouches – see Fig. 5; MSCS C A.III ‘Beloved by …’ – see Fig. 3.1–2,5; MSCS A Colossi – see Fig. 5.10; RSCS – see Fig. 9.1–5.

Two medium-size commemorative faience scarabs (Type D) were found in the Aegean – at Kydonia/Khania (Crete – Fig. 8.5 a–b ) and Ialysos (Rhodes). Interestingly, the names of both sites are depicted on the base of a colossus found in the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III at Kom el-Hetan (Cline Reference Cline1987, 2–13).

Since no other types of LCS or MSCS were found in the Aegean, while in Canaan all types were found at the same sites (Table 3 – ‘Canaan’), the obvious conclusion is that the production of the medium-size commemorative faience scarabs (Type D) started before the production of the other three MSCS types (Types A–C). As shown above, the latter are connected to Amenhotep III's first Sed festival, and so are the associated MSCS of the ‘faience group’ (Type D) that may have been produced already from the king's Regnal Year 25 onwards.

MYCENAE AND SELLOPOULO: ADDITIONAL FINDS WITH THE NAMES OF AMENHOTEP III AND TIYE IN THE AEGEAN

Two additional Aegean sites – Mycenae in mainland Greece and Sellopoulo (Knossos) in Crete – that yielded finds bearing the name of Amenhotep III, are also included in his ‘Aegean List’ on the base of a colossus from Kom el-Hetan.

Mycenae

Eleven faience ‘plaques’ bearing the cartouches of Amenhotep III were found in various locations at Mycenae.Footnote 22 Two faience scarabs bearing the name of Tiye were also found at the same site (Cline Reference Cline1987, 8, 24–5, table 1 D–E, pl. I.3–4). In addition to these finds one should note also a vase with the name of Amenhotep III made of Egyptian blue frit (Cline Reference Cline1994, 216 catalogue II no. 734, pl. 3.10), a material favoured by the Mycenaeans.Footnote 23 It is the consideration of all these inscribed finds made of faience (and Egyptian blue frit that resembles faience) as one group (see already Cline Reference Cline1990, 210 n. 51) that leads us to conceive of these Mycenaean finds, together with the above-mentioned medium-size commemorative faience scarabs from Khania and Ialysos, as a pan-Aegean assemblage. Such a conception allows a better understanding of the circumstances of their arrival in the region than the study of the Mycenae ‘plaques’ alone.

Objects made of faience were highly appreciated by the Egyptians (Friedman Reference Friedman1998, 15). Faience finger-rings bearing the cartouches of a pharaoh and sometimes also of his wife were considered as very special, and were given as presents to participants in various festivals, banquets and the like (Hayes Reference Hayes1951, 231). The presence of faience objects bearing the royal names of Amenhotep III and Tiye at Aegean sites that also appear in the ‘Aegean List’ should therefore be considered as very meaningful, especially since these objects (except for the ‘plaques’) could never serve as raw materials (cf. Cline Reference Cline, Laffineur and Greco2005, 47–8). Apparently, both the Egyptians and the Aegeans appreciated faience objects, especially with royal names, as highly prestigious presents to donate or receive.

The original suggestion that the ‘Aegean List’ from Kom el-Hetan should be interpreted as an itinerary of a single journey made by an Egyptian official embassy during the days of Amenhotep III still seems very convincing, especially in light of the archaeological evidence from the Aegean supporting it (Hankey 1981, 45–6; Cline Reference Cline1987; Reference Cline, Laffineur and Greco2005, 47).Footnote 24 As long observed, the Amenhotep III/Tiye faience objects in the Aegean are not travellers' trinkets, bric-a-brac, or the product of casual trade (Hankey 1981, 45; see also Cline 1998, 246–7). Nor do they seem to have arrived in this region by means of intermediary merchants, since it is hard to perceive the ‘Aegean List’ as based on random information gathered from such sources.Footnote 25 Notably, not even one additional faience scarab of any size with the prenomen of Amenhotep III was found in Crete, other Aegean islands or mainland Greece in addition to those already registered by Cline almost two decades ago (Cline Reference Cline1994, 144–50 nos. 104–53).

Sellopoulo (Knossos)

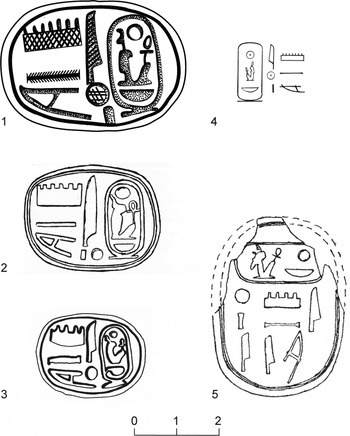

The only regular-size commemorative scarab (RSCS) of Amenhotep III in the Aegean – originally said to be made of faience – was found at Sellopoulo (Knossos) Tomb 4 dated to Late Minoan IIIA1 (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, 203, 216–17, 224 no. J 14, figs. 10.J14, 14.F, pl. 38 g–i; our Fig. 9.1–5). As mentioned previously, this site is also included in the ‘Aegean List’ of Kom el-Hetan.

Fig. 9. Top: Sellopoulo (Knossos) scarab and a ‘real’ ‘Star of the Two Lands’ scarab. 1: Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, pl. 38 g; 2: Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, pl. 38 h; 3: Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, 218 fig. 14 F; 5: Keel and Kavoulaki Reference Keel, Kavoulaki, Karetsou, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Papandakis2001, 321 no. 330; 6: Pier Reference Pier1906–7, 91, pl. 8.1346. Bottom: The complete god's name – ‘Amun, the primeval God of the Two Lands’ – a: Lepsius Reference Lepsius1849–1913 V 3, 72 line 13; b: Helck Reference Helck1957, [1674] – inverted, c: Davies Reference Davies and Helck1992, 12 [1674].

I.E.S. Edwards proposed that the epithet attached to the cartouche with the prenomen of Amenhotep III should be read as sbA tAwj – ‘star of the Two Lands (i.e. Upper and Lower Egypt)’. He noted, however, that ‘the first sign is almost certainly the five pointed or rather rayed star inverted (sbA). As a rule the vertical ray points upwards, whereas in this case it points downwards’. The inversion of the star suggested to Edwards that ‘it was made by someone who was not familiar with the hieroglyphic script, perhaps a foreigner’ (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, 216–17).

The first to suggest an alternative interpretation concerning the hieroglyphic sign of the ‘inverted star’ was Eric Cline. He proposed the reading ‘“Nb mAat Ra pA tAwj” – “…he/the one of the Two Lands”, in which there is no need to invert the first sign of the epithet, … but there are no other examples or direct parallels immediately apparent for such reading.’ (Cline Reference Cline1987, 12 n. 56). Cline repeated this idea later, describing the scarab as ‘inscribed with prenomen and epithet of the pharaoh: “Nb mAat Ra sbA [pA] tAwj” (“Neb-Ma’at-Re Star [He] of the Two Lands”)' (Cline Reference Cline1994, 147 catalogue II no. 128 with detailed bibliography).

We would like to add two additional observations that support Cline's alternative identification of the ‘inverted star’ hieroglyphic sign:

-

1. The photograph of the inscribed base of the Sellopoulo scarab used in the report (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, pl. 38 g; our Fig. 9.1) is highly misleading.

The diagonal lighting used from behind the upper-left corner had actually blurred the hieroglyphs of the epithet that occupies the entire left side of the scarab's base, or its sphragistic surface. At the same time it nicely emphasised the cartouche located on the right side.Footnote 26

It is only with the publication of an additional photograph of the same scarab – with lighting from a different angle – that the epithet is shown correctly (Keel and Kavoulaki Reference Keel, Kavoulaki, Karetsou, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Papandakis2001, 321 no. 330; our Fig. 9.5), yet now the cartouche is less clear.Footnote 27

Since the original drawings of the scarab and its modern impression (Fig. 9.3) were affected by the lighting of the first photograph, a new drawing, based on the best parts in both photographs, is required and presented here (Fig. 9.4).Footnote 28

The pointed wings, the legs, the tail and the typical duck's head penetrating the frame are all clear,Footnote 29 and point to its identification with the flying pintail duck that appears in Egyptian writing as the hieroglyphic sign pA used as the phonogram ‘the’ (Gardiner Reference Gardiner1973, 472 sign-list G 40; Allen Reference Allen2000, 432 sign-list G 40; Hannig Reference Hannig1997, 1052 Zeichenliste [Gardiner] G 40).

Flying pintail ducks appear in Egyptian art both on small finds – such as on a scarab from Memphis (Petrie Reference Petrie1909, pl. 34.25), and on a painted pavement at Tell el Amarna (Petrie Reference Petrie1894, pls. 2–4).Footnote 30 The pointed wings of this hieroglyphic sign depicted on one of the jar sealings found at Tell el Amarna (Petrie Reference Petrie1894, pl. 21.52) comprise an exact parallel to those on the Sellopoulo scarab.

The shape of the hieroglyphic sign tA, which serves as the ideogram ‘earth’, ‘land’, and its duplication that creates the name tAwj ‘Two Lands (i.e. Upper and Lower Egypt)’, is now also clear. It shows the ‘flat alluvial land with grains of sand’ (Gardiner Reference Gardiner1973, 487 sign-list N 16) or ‘strip of land with sand’ (Allen Reference Allen2000, 436 sign-list N 16 – variant N 16d, i.e. with two instead of three grains of sand). Although correctly identified, its original drawing is erroneous (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, 218 fig. 14 F; our Fig. 9.3).

-

2. A scarab with the epithet sbA tAwj – ‘star of the Two Lands (i.e. Upper and Lower Egypt)’ – was already published by Garrett Chatfield Pier more than a century ago (Pier Reference Pier1906–7, 81 no. 1346, pl. 8.1346; Jaeger Reference Jaeger1982, 157 ill. 446, 308 ill. 722) (Fig. 9.6). This scarab clearly exemplifies how the first sign (sbA) in a case of such a ‘genuine’ epithet was depicted.

Following our support of Cline's alternative identification of the ‘inverted star’ hieroglyphic sign on the Sellopoulo scarab we would like to address four additional aspects related to this scarab: a) Who made it? b) What does it commemorate? c) What is the meaning of the epithet appearing on it? d) When was it made?

a) Who made the Sellopoulo scarab?

Edwards' claim that the Sellopoulo scarab was made by a foreigner unfamiliar with the hieroglyphic script (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974, 216–17; followed by Lilyquist Reference Lilyquist and Hachmann1996, 146 n. 120 and Manning Reference Manning1999, 222 n. 1072) seems rather questionable. The carving of the small details in the design of the flying pintail duck, and of the two grains of sand, attached to each of the strips of land (Fig. 9.4), clearly demonstrates that the engraver of this glazed steatite scarabFootnote 31 was a literate Egyptian well entrenched in Egyptian art (contra Phillips Reference Phillips1991, 597 n. 252: Reference Phillips2008, 136 n. 765 with reservations; Manning Reference Manning1999, 222 n. 1073; Keel and Kavoulaki Reference Keel, Kavoulaki, Karetsou, Andreadaki-Vlazaki and Papandakis2001, 321 no. 330).

b) What does the Sellopoulo scarab commemorate?

In his description of the ‘genuine’ ‘Star of The Two Lands’ scarab (Fig. 9.6), Pier added a note that the epithet is the ‘name of the royal barge’ (Pier Reference Pier1906–7, 81 no. 1346). Apparently, more regular-size commemorative scarabs commemorate special royal boats, and the scarab from Sellopoulo may be one of them.

The seminal work concerning the names given to Egyptian war boats and royal boats was published more than a century ago by Wilhelm Spiegelberg (1896, 81–6), who collected 22 ship names.Footnote 32

-

• The epithet sbA tAwj ‘Star of the Two Lands (i.e. Upper and Lower Egypt)’ depicted on a regular-size commemorative scarab of Amenhotep III (Figs. 9.6, 10.1) – previously appeared as the name of a war and royal boat during the days of Thutmose III (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 81 no. 4 = Casson Reference Casson1986, 349 n. 26 = Jones 1988, 238 no. 36) (Fig. 10.1 a ).

-

• The epithet sbA m mn-nfr ‘Star in Memphis’ depicted on a regular-size commemorative scarab of Thutmose IV (the father of Amenhotep III) (Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 79 [no. 411 = 488], 186 no. 411, 213 no. 488 = Jaeger Reference Jaeger1982, 157 ill. 445) (Fig. 10.2) – appears as a name of an undated New Kingdom boat (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 86 no. 22 = Schulman Reference Schulman1964, 137 no. 325a, c–d, 165 no. 495b = Casson Reference Casson1986, 349 n. 25 = Jones 1988, 238 no. 38) (Fig. 10.2 a ).

-

• The epithet xa m mAat ‘Appearing in Truth’ depicted on a regular-size commemorative scarab of Amenhotep III (Śliwa Reference Śliwa1985, 22 no. 11, pl. 2.11 with bibliography for parallels) (Fig. 10.3) – appears as a name of a war and royal boat during the days of this pharaoh (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 83 no. 9 = Schulman Reference Schulman1964, 136–7 nos. 321a, 325b, 166 nos. 494f and h, 495b = Casson Reference Casson1986, 349 n. 22 = Jones 1988, 237 no. 33) (Fig. 10.3 a ), and also as the name of the temples he had built at Karnak and Soleb (Sudan).

Fig. 10. Five scarabs commemorating boat names. 1: Pier Reference Pier1906–7, 91, pl. 8.1346; 1a: Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 81 no. 4; 2: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 186 no. 411; 2a: Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 86 no. 22; 3: Śliwa Reference Śliwa1985, 22 no. 11; 3a: Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 83 no. 9; 4: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 191 no. 496; 4a: Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 83 no. 9 – variant; 5: Matouk Reference Matouk1971, 191 no. 497; 5a: Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 83 no. 10.

Two boat names appear also on the large commemorative scarabs:

-

• The name of Amenhotep III's boat just mentioned – ‘Appearing in Truth’ (Fig. 10.4 a ) – also appears on large commemorative scarabs ‘Type B’ – Wild bull-hunt scarabs = Regnal Year 2Footnote 33 (Fig. 10.4). This is a good opportunity to show that this epithet is also part of the pharaoh's ‘Horus Name’ (kn xaj-m-MAat) (Beckerath Reference von Beckerath1999, 140–1 Amenophis III H1a and H1b) ‘Strong Bull who appears/rises in Truth’ (see lines no. 2 on scarabs in Fig. 10.4–5).

-

• A boat named Jtn THn ‘Aton Gleams’, ‘Aton Glitters’ or ‘The Dazzling Sun Disc’ (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 83 no. 10 = Schulman Reference Schulman1964, 165 no. 495b, 168 no. 509a = Casson Reference Casson1986, 349 n. 32 = Jones 1988, 231 no. 4) (Fig. 10.5 a ) – is mentioned on large commemorative scarabs Type E – Irrigation Basin/ Lake scarabs = Regnal Year 11Footnote 34 (Fig. 10.5 and also in Fig. 11) (see further discussion below).

Fig. 11. The appearances of the name ‘Dazzling Sun Disc’ from Amenhotep III's Regnal Year 32 and later. Hayes Reference Hayes1951, figs. 5:21, 9:108, 25:E–G, 27:HH, 31:S24–S26,S30–S31, 32:S59,S64, 34:R44.

c) What is the meaning of the epithet appearing on the Sellopoulo scarab?

Cline's reading of the first hieroglyphic sign in the epithet of the Sellopoulo scarab as pA was an important step in deciphering the epithet. However, his suggestion – pA tAwj, ‘he/the one of the Two Lands’ or ‘[He] of the Two Lands’– raises grammatical difficulties, since pA – while independent – is used only as one of the demonstrative pronouns ‘this’ or ‘the’ (Gardiner Reference Gardiner1973, 85–86 [§§110–11]; Allen Reference Allen2000, 53–4 §5.10). We would like to propose two alternative interpretations of the epithet, both based on the assumption that the original name was shortened due to space limits on such a small scarab.

-

• The first alternative suggests that the missing hieroglyphic sign is the determinative for ‘boat, ship’ (Gardiner Reference Gardiner1973, 498 sign-list P 1). This is based on the comparison with the boat name ‘The Ship of the North’ (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 81 no. 2 = Casson Reference Casson1986, 349 n. 38 = Jones 1988, 235 no. 22). If accepted, the name of the commemorated boat might be ‘The Ship of Egypt’.

-

• The second alternative suggests that the hieroglyphic sign pA is a shortening of the word pAw.tj ‘primeval god’ (Hannig Reference Hannig1997, 271). The combination pAw.tj tAwj ‘A primeval god of Egypt’ refers to the Eighteenth Dynasty epithet of the Egyptian sun-god Amun (cf. Erman and Grapow Reference Erman and Grapow1926–63 vol. 1, 497 2/3).Footnote 35 This suggestion may be supported by other boat names incorporating deities' names, such as ‘Amun’ (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1896, 85 no. 17 = Jones 1988, 231 no. 2) and ‘Aton’ (Schulman Reference Schulman1964, 165 no. 493a, 168 no. 509b = Casson Reference Casson1986, 349 n. 32 = Jones 1988, 233 no. 14).

Additional search through the digitised slip archive of the Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache has culminated in finding a crucial clue for dating the Sellopoulo scarab – the Granite Stele that lies behind the Colossi of Memnon at Kom el-Hetan.

According to ‘Slip 12’ which refers to the word pAw.tj, the words Jmn pAw.tj tAwj – ‘Amun, the primeval God of the Two Lands’ – are preceded by the words ‘my father’ ending with a determinative of an enthroned god holding a flagellum. The same hieroglyphic sign appears in the same line (13) a few words earlier.Footnote 36 According to Wolfgang Helck's collection of Amenhotep III's historical inscriptions (Helck Reference Helck1957, 1674) the first hieroglyphic sign is part of the word ‘nobility’ (Fig. 9 b and c).

Since the words ‘noble’ and ‘nobility’ (cpsi/cpss) appear with ‘man of rank seated on chair’ (Gardiner Reference Gardiner1973, 447 sign-list A 51) and not with an enthroned god we turned to the original publication by Lepsius (1849–1913 III, 72 lines 12–13 = Haeny 1981, Falttafel 5b) (see Fig. 9 a). There this strange situation came to its solution. The word ‘nobility’ is with the chair (indicated by the triangles, and by purple shading online), while the words ‘[my] father Amun, the primeval God of the Two Lands’ include the determinative of the enthroned god (indicated with an arrow).

We suggest that line 13 on the Granite Stele of Amenhotep III refers to the actual sculpture of ‘Amun the primeval God of the Two Lands’. Since this god was worshipped in the area of Medinet Habu (Otto Reference Otto1975, cols. 245–6), it is proposed here that his statue stood in the ‘Temple of Amun’ at Malkata (see Fig. 6 [upper-right corner]) – the temple that was built for Amenhotep III's Jubilees.

d) When was the Sellopoulo scarab made?

Our discussion so far allows us to suggest two dating options for the production of the Sellopoulo scarab: the one based on its interpretation as commemorating a royal boat and the other based on its interpretation as commemorating the placing of a deity statue:

-

1. The time frame for the production of the regular-size commemorative scarabs of Amenhotep III may have been longer than that of the medium-size commemorative scarabs, since following the Eighteenth Dynasty tradition (see above) their production could have started already in the pharaoh's first regnal year and continued to his last.

However, based on the understanding that the scarab could have arrived at Knossos in the course of the renowned Aegean journey, we suggest applying the production date assigned above to the medium-size commemorative faience scarabs (Type D), i.e. Amenhotep III Regnal Year 25 and onwards, also to the Sellopoulo scarab.

-

2. Our new reading of the epithet may provide a somewhat later terminus post quem for the Sellopoulo scarab. The epithet was shown to relate to a statue of ‘Amun the primeval God of the Two Lands’ that stood in a temple at Malkata built by Amenhotep III for his Jubilees. We can therefore determine that the scarab must have been produced in relation to Amenhotep III's first Jubilee [Regnal Year 30], between his Regnal Year 28 and Regnal Year 34 (like MSCS Types A–C).

Thus, the above two independent dating options lead to the following conclusion: the regular-size commemorative scarab from Sellopoulo commemorating either a boat named after the god Amun or its statue was most probably produced between Amenhotep III Regnal Year 25 and Regnal Year 28. This dating harmonises with the assumption that the scarab must have reached Knossos by means of the Egyptian embassy to the Aegean before the erection of the statue with the ‘Aegean List’ at Amenhotep III's temple in Kom el-Hetan (most probably during Regnal Year 28).

AMENHOTEP III LARGE COMMEMORATIVE SCARABS – A NEW DATING

As already mentioned, the first challenge to the inner chronology of the large commemorative scarabs of Amenhotep III was introduced by Berman (Reference Berman, Kozloff and Bryan1992, 68) advocating that, although bearing different regnal years, the entire group was produced in one workshop at the same time. However, his suggestion was still bounded by the 11th regnal year of Amenhotep III – the latest to appear on the LCS.

Before suggesting a new production date for the LCS series, we would like to begin with a new interpretation related to Type A – ‘Marriage’/Boundaries scarabs, and Type D – Gilukhepa/Kirgipa scarabs.

-

1. The mention of Tiye's parents Yuia and Thuia on Types A and D scarabs may hint at the exceptional phenomenon that a special tomb was quarried for them in the Valley of Kings (KV 46), despite the fact that their roots were not of royal origin (Romer Reference Romer1981, 197–210 Yuya and Tuya; Grajetzki Reference Grajetzki2005, 58).

-

2. The mention of the number of women (317) that accompanied the Mitannian princess Gilukhepa/Kirgipa (Type D) may hint at the size of the harem at Malkata (Stevenson Smith Reference Stevenson Smith1958, 160–72, figs. 54–5) or alternatively at Gurob (Kemp Reference Kemp1978, esp. 132; Lacovara Reference Lacovara and Phillips1997; Shaw Reference Shaw2012).

If our suggestion is sound, then the above LCS types could join the Irrigation Basin/Lake scarabs (Type E) and therefore these three types of large commemorative scarabs would share the same meaning as the medium- and regular- size commemorative scarabs, i.e. commemoration of architectural elements.

Since LCS are known from sites in Canaan and Cyprus, but not from Aegean, Babylonian or Mitannian contexts (Table 1), their production may have been closer in time to the Sed festival, much like the suggested production date for the MSCS of the three non-faience types (A–C) – i.e. between Amenhotep III regnal years 28 and 34.

This time span for LCS manufacture can be further narrowed on the basis of the following observations:

-

1. If the only known Thutmose IV large commemorative scarab is indeed a fake (Blankenberg-Van Delden Reference Blankenberg-Van Delden1969, 166 with previous bibliography), then it is logical that the innovative idea of producing LCS first appeared in the later days of Amenhotep III, closer to the days of Amenhotep IV – of whom at least three scarabs are known (Blankenberg-Van Delden Reference Blankenberg-Van Delden1969, 166–7 with previous bibliography).Footnote 37

-

2. The name of the royal boat ‘Aton Gleams’ (see above) – mentioned on large commemorative scarabs of Type E, or Irrigation Basin/Lake Scarabs (see Fig. 10.5 and Fig. 11) – points to the possibility that all the series was manufactured even after the first Jubilee, i.e. after the Regnal Year 30 of Amenhotep III.

This is based on two or three stamped wine jar stoppers from Malkata where the rebus writing of the name of Amenhotep III is inserted in the dazzling sun disc sailing on boat (Hayes Reference Hayes1951, 157–8, 170 fig. 25 E–G) (Fig. 11 E–G). These stamped stoppers are not dated, but the wine and ale jars coming from the royal or temple estate ‘The House of Splendour-of-Aten’ (Hayes Reference Hayes1951, 96 g), 178–9, figs. 5.21 and 9.108) are dated exclusively to Regnal Year 32 (Fig. 11: wine 21, ale 108), i.e. they were stored at Malkata for the second Jubilee held in Regnal Year 34.Footnote 38

This suggestion could be supported by three additional observations.

-

• ‘Aton Gleams’ was related to Amenhotep IV by seal impressions from Amarna and a scarab from Sesebi (Kuckertz 2003, 89–90 no. 35, n. 892, 136).

-

• Several items of the LCS were found in places where some of the Amarna Letters were sent from. And ‘… the correspondence begins around Regnal Year 30 of Amenhotep III and ends no later than Tutankhamen's Regnal Year 1, when the pharaoh and his court left Amarna’ (Moran Reference Moran1992, xxxiv–xxxv; Weinstein Reference Weinstein, O'Connor and Cline1998, 225 n. 8 = Campbell 1964, 134–5 Chart E).

-

• It would be very strange if the production of those scarabs – which carry texts that are recognised as small literary works (Meltzer Reference Meltzer1989/90) – had stopped during the early years of the reign of Amenhotep III. Moreover, two such scarabs were found at Amarna (Table 1, Types C and E).

As described above (Table 1 and Table 3) such a scarab was uncovered during earlier excavations at Tel Beth-Shemesh, but unfortunately found in a secondary and later context.Footnote 39

CHRONOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

In the traditional archaeological–historical chronology of the Aegean Late Bronze Age, Sellopoulo Tomb 4 is considered as a linchpin for the synchronisation between Late Minoan/Late Helladic IIIA1 and Amenhotep III (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974; Warren and Hankey Reference Warren and Hankey1989, 146–8; Betancourt Reference Betancourt, Balmuth and Tykot1998, 293; Hatzaki Reference Hatzaki and Momigliano2007, 222–3). Following this synchronism and an assumed date for the beginning of Late Helladic IIIA2 about 1370/1360 bc, Warren and Hankey (Reference Warren and Hankey1989, 148–9, 169 table 3.1) correlated the Late Minoan IIIA1 period with the first twenty to thirty years of Amenhotep III's reign.Footnote 40 It should be remembered that, though indicating that Late Minoan IIIA1 must synchronise at least with the beginning of Amenhotep III's reign, the scarab from Sellopoulo was supposed to provide no clue for a more precise date of the synchronisation. Indeed, a variety of opinions can be found concerning the span of Late Minoan IIIA1 or the beginning of Late Minoan IIIA2 as implying the end of the former.Footnote 41 In any case, the traditional prevalent opinion is that Late Minoan IIIA1 was a short period lasting no more than a generation (e.g. Warren and Hankey Reference Warren and Hankey1989, 147; Popham 1990, 27–8; Mountjoy Reference Mountjoy1993, 4 table I).

Wishing an earlier date for Late Minoan IIIA1, adherents of the radiocarbon-based Aegean high chronology criticised the evidence from Sellopoulo in order to ‘distance’ Amenhotep III from Late Minoan IIIA1 and minimise the assumed overlap between this period and his reign (Manning Reference Manning1999, 220–2). For that reason it was suggested that the scarab of Amenhotep III found with the last burial of Tomb 4 was already old when deposited. Moreover, building on the view that some supposed peculiarities in the hieroglyphic inscription of the scarab may hint at its manufacture by a foreigner rather than by Amenhotep III workshops, the scarab was considered to postdate this pharaoh's reign (above). With the traditional Sellopoulo linkage between Late Minoan IIIA1 and Amenhotep III removed, the way opens to set the end of Late Minoan IIIA1/beginning of Late Helladic IIIA1 shortly before, or at the latest very early in, the reign of Amenhotep III (Manning Reference Manning1999, 223, 229, 338).Footnote 42 Notably, the lack of a clear date for Sellolpoulo's scarab and a Late Minoan IIIA1/Amenhotep III synchronism is reflected also in recent modified traditional chronological schemes, whereby Late Minoan IIIA1 has ended already during the early years of Amenhotep III, c.1375/1370 bc (Cline Reference Cline, Aruz, Benzel and Evans2008, 453, fig. 14.5; Tartaron Reference Tartaron2008, 84 table 1).

What are the implications of the new finds from Beth-Shemesh and of our revisit of the Sellopoulo scarab for the chronological issues reviewed above?

The analysis of the Amenhotep III scarab from Beth-Shemesh involved a broader study of Amenhotep III scarabs aiming at refining their chronology. The study has identified a number of categories or types of commemorative scarab (MSCS Types A–C) referring to colossal statues of Amenhotep III and Tiye, palaces, statues of deities and even boats. All this intensive building activity is related to the first Jubilee – the Sed festival – celebrated in the 30th regnal year of Amenhotep III. Most of the royal colossi and deities' statues depicted or referred to by the medium-size commemorative scarabs were erected in Amenhotep III's magnificent mortuary temple at Kom el-Hetan. One of the important insights gained by the study of this neglected category of commemorative scarabs – which includes the new scarab from Beth-Shemesh – is that they were produced at a date close to the first Sed festival, presumably between Amenhotep III's Regnal Year 28 and Regnal Year 34 (the date of the second Jubilee). An earlier terminus post quem – Regnal Year 25 – is assumed for the beginning of manufacturing faience medium-size commemorative scarabs (Type D).

Our investigation of the Sellopoulo scarab led to similar conclusions. Contrary to some previous views that diminished the importance of the scarab, in the wider framework of Amenhotep III scarabs we categorised it as a regular-size commemorative scarab – the only one of its kind found in the Aegean. Apparently, the scarab was engraved by a literate Egyptian rather than by an unprofessional foreigner as argued before. A new reading of its epithet as related to ‘Amun the primeval God of the Two Lands’ that stood in a temple at Malkata built by Amenhotep III for his Jubilees indicates that the scarab commemorates either a boat named after this god or the statue itself. Following these two alternative interpretations it seems that the Sellopoulo scarab was produced between Amenhotep III's Regnal Years 25 or 28 and up to his Regnal Year 34, most probably around Regnal Year 28.

Students of Aegean archaeology have long been troubled by the date of the envisioned Egyptian voyage or embassy to the Aegean during the reign of Amenhotep III. Our new dating of the medium-size commemorative faience scarabs (found among others at Khania and Ialysos) and the regular-size scarab of Sellopoulo (Knossos), which relates their production to the first Jubilee (Sed festival) of Amenhotep III, helps in narrowing the possible time span for such a voyage. It seems that the Egyptian embassy, carrying a load of faience objects bearing the royal names of Amenhotep III and Tiye, took a mission to the main centres of the Aegean during Regnal Year 28 of this pharaoh. The itinerary of the mission was carved not much later on the base of a statue in the magnificent mortuary temple of the king.

The discovery at Tel Beth-Shemesh of an Amenhotep III scarab together with two Late Minoan IIIA1 cups strongly supports the synchronisation between the two, long acknowledged from the finds at Sellopoulo Tomb 4 yet recently questioned. Importantly, the Late Minoan IIIA1 pottery and the Amenhotep III scarab from Beth-Shemesh were found in a sealed context (destruction layer) independently dated to Late Bronze IIA (first half of the fourteenth century bc) by the local and imported Cypriot pottery assemblage. Moreover, the identification of the Beth-Shemesh scarab as a commemorative scarab dated to the last decade of Amenhotep III's reign provides a firm testimony that Late Minoan IIIA1 continued at least to these days, if not to the very end of his reign (since the scarab gives a terminus post quem for its deposition with the Minoan pottery).

This conclusion is further confirmed by the new reading and interpretation of the Sellopoulo scarab as a commemorative scarab from the mid-third decade of Amenhotep III's reign. Though the archaeological context of Sellopoulo Tomb 4 may seem less secure than that of Beth-Shemesh due to its funerary character, it should be recalled that the last burial with the Late Minoan IIIA1 pot and the Amenhotep III scarab was not disturbed by later interments (Popham, Catling and Catling Reference Popham, Catling and Catling1974).

In their seminal work on Aegean Bronze Age chronology Warren and Hankey (Reference Warren and Hankey1989, 137) bring forth an important truism in chronological studies: find contexts only provide termini ante quos for the use of imported objects in these contexts; that is, the objects could be older than their contexts. In other words, when considering Aegean goods found abroad their manufacture is unlikely to be precisely contemporary with their final archaeological context. Furthermore, pottery deposited in a tomb at Knossos or Mycenae is likely to be nearer the date of its manufacture than identical pottery found in a deposit where distance alone imposes a time lag (Hankey Reference Hankey and Åstrom1987, 41). This being said, it should be emphasised that when several pots of a particular ceramic style occur in different places, yet are contextually datable to a single Egyptian reign, it is unlikely that they were all heirlooms or had all been used for a long time. In such cases, approximate synchronism of the Aegean ceramic style with the Egyptian reign is reasonable (Warren and Hankey Reference Warren and Hankey1989, 137).

As we have seen, the latter insight concurs with our double case. While it is certainly possible that the Late Minoan IIIA1 pottery from Sellopoulo and Beth-Shemesh was produced earlier than the associated scarabs of Amenhotep III, it should be noted that no pottery of the subsequent Late Minoan IIIA2/Late Helladic IIIA2 horizon was found in either context. Apparently, two culturally different and geographically remote contexts – a tomb in Crete and a destruction layer in Canaan – tell the same story: Late Minoan IIIA1 was in vogue at least until the last decade of Amenhotep III's reign in the mid-fourteenth century bc. It is only then that the dividing line between Late Minoan IIIA1 and Late Minoan IIIA2 should be drawn. This conclusion has important implications for the political and cultural history of Knossos and may anchor the sequence of events of the Final Palatial period in a more solid chronological framework.