INTRODUCTION

The manipulation of archaeological agendas by the Nazi regime in Germany (1933–45) and Austria (1938–45), as a means of endorsing its ideology during the Third Reich, has featured prominently in the reassessment of archaeology's past (Bollmus Reference Bollmus1970; Kater Reference Kater1974; Arnold Reference Arnold1990; Halle and Schmidt Reference Halle and Schmidt2001, 270–4; Altekamp Reference Altekamp2016 for extensive bibliography).Footnote 1 The role of organisations, such as the SS-Ahnenerbe (Ancestral Heritage) and the Amt Rosenberg (Rosenberg Office), or military institutions in implementing the Nazi-era archaeological projects has also been critically evaluated after the release of World War II archival records in the early 1990s (e.g. Arnold and Hassmann Reference Arnold, Hassmann, Kohl and Fawcett1995; Härke Reference Härke2002; Hassmann Reference Hassmann2002; Kuhnen Reference Kuhnen2002; Arnold Reference Arnold2006, 11–15, 21–2; Altekamp Reference Altekamp, Elvert and Nielsen-Sikora2008; Krumme Reference Krumme2012; Vigener Reference Vigener2012a). Following a paradigmatic shift of emphasis from collective to personal narratives many studies have recently outlined the need to study the personal biographies of archaeologists and their methodological legacy in conjunction with information from contemporary sources (Steuer Reference Steuer and Steuer2001, 1–2; Eickhoff Reference Eickhoff2005, 73–5; Brands and Maischberger Reference Brands and Maischberger2012; Bernbeck and Pollock Reference Bernbeck and Pollock2013, 4–5).Footnote 2 On the other hand, most of the aforementioned studies have been only marginally concerned with the recruitment of young professionally trained archaeologists into the Wehrmacht (the German armed forces), their motivations and their impact on the development of research agendas. Thus, it is necessary to examine more closely their individual paths of professional advancement, especially as it has been demonstrated that the scenario of the ‘political entrapment’ of archaeologists during the Third Reich does not stand up to close scrutiny (Halle and Schmidt Reference Halle and Schmidt2001). This paper starts from the premise that discussion should be grounded in an understanding of the social and ideological background prevailing in Germany and Austria during the pre-World War II era (Schlanger Reference Schlanger2004, 165). We essentially need to explore how the core values of the National Socialist New Order (Neuordnung), namely the ideas of ‘people's community’ (Volksgemeinschaft) and racial exclusion, were filtered through personal worldviews and individual interests in this time of social conflict (Föllmer Reference Föllmer2013, 1109–11, 1131–2). A generation of archaeologists pursuing or already holding academic posts were confronted with the challenge of adapting to the political system, especially in the period after 1933 and 1938 when the radicalisation of German and Austrian universities, respectively, intensified (Schücker Reference Schücker, Van der Linde, Van den Dries, Schlanger and Slappendel2012, 165). With the exception of a minority of scholars, not exclusively of Jewish decent, who migrated to the United States or England (Davis Reference Davis2010, 134–42; Manderscheid Reference Manderscheid2010, 47–8; Lorenz Reference Lorenz2012; Obermayer Reference Obermayer2014), the ideological stances taken by most German and Austrian academics were not always clear. Accordingly, individual case studies can help to create a more nuanced exploration and to detect degrees and channels of political radicalisation (Altekamp Reference Altekamp, Elvert and Nielsen-Sikora2008, 267; 2016, 23–8).

The intention of this paper is to document, through primary sources, the biography and archaeological activity of the Austrian archaeologist August Schörgendorfer (1914–76) during the World War II occupation of Greece. In the years 1941–2, Schörgendorfer served on Crete as a junior officer of the Kunstschutz, the ‘Art Protection’ unit of the Wehrmacht that was dedicated to prohibiting any seizure or destruction of cultural heritage (Kott Reference Kott2007, 137–41). Acting in this capacity, he illicitly excavated Tholos Tomb A and a small part of the neighbouring Minoan settlement at Apesokari without authorisation or supervision by the Greek Archaeological Service (Platon Reference Platon1947, 630). According to Schörgendorfer's account, the exploration of Tholos Tomb A bore the characteristics of a rescue excavation, as the tomb had been looted ‘by local tomb robbers and some of the finds had found their way into the Heraklion illicit antiquities market’ (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1951a, 14). This statement reflects his stance that as a representative of the Kunstschutz he had assumed the responsibility for protecting the Cretan antiquities, which lay exclusively with the Greek Archaeological Service. Thus, he presents an example of the ‘embedded archaeologist’ who collaborates with the military in order to rescue antiquities in times of war, characteristic of archaeology as a social discipline from its beginnings to the present day (Teijgeler Reference Teijgeler, Stone and Farchakh Bajjaly2008; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2009, 43). This case study does not contradict this view, but aims to address the interplay between Schörgendorfer's agency and institutional structures, exploring the implications for the Greek archaeological sites under his responsibility.Footnote 3 Both themes – personal and institutional – will emerge through the combined study of official and personal archival testimonies kept in Austria and in Greece, according to the method advocated by Maischberger (Reference Maischberger2002) and Eickhoff (Reference Eickhoff2005).

The strategy of the individual Kunstschutz units to conduct archaeological research in the occupied European lands for the sake of promoting the agenda of Germany's geopolitical expansion evolved in different ways (e.g. Klinkhammer Reference Klinkhammer1992, 483–549; Junker Reference Junker1998, 288–91; Fehr Reference Fehr and Gillett2002, 193; Leube and Hegewisch Reference Leube and Hegewisch2002; Altekamp Reference Altekamp, Elvert and Nielsen-Sikora2008, 199–202). In some cases, this strategy ultimately ended up as organised looting (Heuss Reference Heuss2000; Kowalski Reference Kowalski and Góralski2006). Relevant narratives of the activity of the ‘Referat Kunstschutz’ on occupied Crete are so far grounded either on German (Hampe Reference Hampe1950; Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 475–81; Jantzen Reference Jantzen1995; Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011; Vigener Reference Vigener2012a) or on Greek sources (Petrakos Reference Petrakos1994; Petrakos Reference Petrakos2013; Tiberios Reference Tiberios2013). In order to produce a more balanced reassessment of Schörgendorfer's illicit excavations, I will try to situate his involvement with the Kunstschutz within the wider social, political and disciplinary context. A historical approach to this question is enabled by integrating the historiography of archaeological research with findings from Schörgendorfer's personal file in the Austrian State Archives, as well as from the archives of the German Archaeological Institute and the Greek Archaeological Service. The comparative treatment of these testimonies has the potential to further illuminate the cultural policies of the Wehrmacht and the German Archaeological Institute during the war. This approach seeks also to underline the view that ‘at each of its moments archaeology is practiced in the present’ (Schlanger Reference Schlanger2004, 165). Following the lead of recent relevant studies (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2009), it offers a critical discourse on the connection between politics and scholarship.

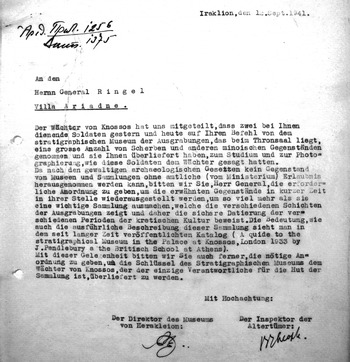

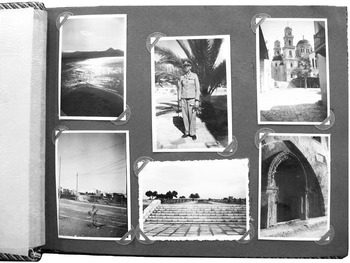

Moreover, Schörgendorfer's contested archaeological itineraries during his service for the Kunstschutz will be reconstructed on the basis of his unpublished photo album of Crete (dimensions 26 × 20 cm), which was kindly made available by his widow. The album comprises 20 reused sheets, as suggested by Schörgendorfer's notes on them that predate the years 1941–2 (Flouda Reference Flouda and Mitsotaki2012). Sixty-six small black-and-white photos, carefully filed and, occasionally, annotated by the archaeologist himself (most probably after the end of the war), supplement the archival evidence on his excavations and autopsies of archaeological sites (Fig. 1). Imbued with emotional significance, these snapshots arguably reveal how Schörgendorfer evoked his past itineraries on the island and, thus, constitute his personal narrative about the place and the people with whom he interacted.

Fig. 1. August Schörgendorfer's photo album (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

AN UNKNOWN ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSONALITY: SOCIAL AND IDEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND

August Schörgendorfer was born on 27 January 1914 at Waizenkirchen near Linz (Upper Austria), into a Catholic family of farmers. The last of 14 children, he followed his parents’ aspirations for him by entering, in 1926, the private Gymnasium Dachsberg in Prambachkirchen in order to become a friar of the Salesian Order Die Oblaten des heiligen Franz von Sales (Flouda, Pochmarski and Schindler Kaudelka Reference Flouda, Pochmarski, Schindler Kaudelka, Casari and Magnani2015, 95). However, the physical and psychological demands of this education took their toll on his health. Despite this fact, his decision to leave the Gymnasium and the order in 1928 at the age of 14 was not approved by his parents, who disowned him (Gerlinde Schörgendorfer, pers. comm.). As they never accepted him back into the family, Schörgendorfer was forced to stop attending classes and started working in the linen and laundry business of the Ammerer family, which was based in the nearby city of Ried im Innkreis. The lack of prospects for social advancement and the years of hardship between 1928 and autumn 1933, during which he changed school three times and finally passed the graduation test at the Bundesgymnasium at Ried (1 June, 1935), provided the background to his future military aspirations (cf. Personal-Nachweis; also Flouda, Pochmarski and Schindler Kaudelka Reference Flouda, Pochmarski, Schindler Kaudelka, Casari and Magnani2015, 95). Α caption written by him in ink on one of the sheets in his photo album, and dated ‘autumn of 1933’, notably reveals that Schörgendorfer may have visited the former Royal Prussian Cadet Academy in Berlin at the time he was a student attending the Bundesgymnasium. This old academy for senior military officers in the district of Gross-Lichterfelde was used between autumn 1933 and spring 1934 for training the members of the paramilitary wing of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (hence NSDAP), the Sturmabteilung (Assault Division) or SA, also known as ‘Storm Troopers’ (Roche Reference Roche2013). This strictly hierarchical, although not elitist, activist organisation expanded rapidly from 1933 until its demotion within the Nazi system in 1934 (Campbell Reference Campbell1998, 179 n. 12). It then continued to indoctrinate and conduct voluntary pre- and post-military training in basic military skills until 1939 (Campbell Reference Campbell1993, 660–2; Grant Reference Grant2004).

At any rate, Schörgendorfer's political affiliation as an extreme-right student is revealed from the fact that in 1934 he officially became a member of the Fatherland Front (Vaterländische Front) (Flouda, Pochmarski and Schindler Kaudelka Reference Flouda, Pochmarski, Schindler Kaudelka, Casari and Magnani2015, 96–7). This was the Austrian fascist political organisation founded in 1933 by the chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, who with the May Constitution of 1934, finally established an authoritarian dictatorship (Ständestaat) and outlawed political parties (Rohsmann Reference Rohsmann2011, 71-5; Emmerich Reference Emmerich2013). Despite its Catholic outlook and its differences from the Nazi rhetoric, the Fatherland Front placed more value on adherence to the notion of Volksgemeinschaft (‘people's community’), namely solidarity based on kindred social values, than to a social class or stratum (Föllmer Reference Föllmer2005, 203, 217–18). This ideological framework, which claimed to offer the potential for self-empowerment (Föllmer Reference Föllmer2013, 1107–9), seems to have appealed to Schörgendorfer. His childhood education under the auspices of the Catholic Church which opposed pan-German ideology (Thorpe Reference Thorpe2011, 85–6) probably played a large role in shaping his patriotic feelings. Nevertheless, his decision to ally himself with the Fatherland Front may also have been driven by the fact that under the regime by Dollfuss only members of this party could advance into university positions (Tálos and Manoschek Reference Tálos, Manoschek, Tálos and Neugebauer2005, 145–6).

EPISTEMOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS AND EARLY IDEOLOGICAL TRAJECTORIES

Schörgendorfer was raised and educated in a transitional period for Austria, as World War I and the 1918 downfall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and empire caused a severe identity crisis for its population (Black Reference Black and Braham1983, 184). In the early 1930s, the discipline of Volkskunde, namely the study of folklore, gained a new political meaning in Germany and Austria through its focus on Germanic mythology and ethnology with racial overtones (Dow and Bockhorn Reference Dow and Bockhorn2004, 24–56). Notions of glorifying Germanic antiquity or ‘Germanicness’ (Germanentum) became a leading feature of ‘völkisch’ groups and academics before Hitler rose to power in 1933 (Arnold Reference Arnold2006, 10–11); this phenomenon was similar to the notion of ‘Romanness’ (Romanità) that prevailed during the Italian fascist regime (Mees Reference Mees2004, 255–6). Thus, the works of the leading German figure of prehistoric archaeology, the Berlin professor Gustaf Kossina, propagated the ‘racial principle’. The latter meant the equation of cultural areas, as defined by homogeneous archaeological typologies, with the presence of certain races throughout the ages (Grünert Reference Grünert2002, 72–3). Through this methodology all achievements of Greek or Roman origin were attributed by Kossina to a Germanic influence (Mees Reference Mees2004, 257–60). Ethnocentric studies like these also fuelled propagandistic or populist publications. For example, in the March 1935 issue of the educational magazine Der Schulungsbrief (‘The Training Dispatch’, cf. Mühlenfeld Reference Mühlenfeld, Swett, Ross and d'Almeida2011, 209) most ethnic groups – including the Etruscans, the Greeks and the ‘Indo-Europeans’ – were stated to have their origins in Germany and south Scandinavia (Pape Reference Pape, Hausmann and Müller-Luckner2002, 340–2, fig. 11). In this way, archaeology was instrumentalised and transformed into an ideological tool for Germany's aggressiveness.

The destruction of German federalism and democracy was also enthusiastically endorsed by many historians teaching at German universities, who dreamt of an authoritarian alternative to the Weimar Republic (Schönwälder Reference Schönwälder1997, 134; Beller Reference Beller2001, 314). As noted above, in Austria – which followed a separate path – an authoritarian state became a reality in 1934, when Dollfuss banned all political parties and political opponents were victimised, persecuted or eventually driven into exile (Fleck Reference Fleck, Marks, Weindling and Wintour2011, 194; Rohsmann Reference Rohsmann2011, 82-7). It was with such developments in the background that Schörgendorfer graduated on 1 June 1935. He received a general education in the humanities; his classification as ‘Excellent’ in all philological classes paved his road to further Classical studies (G. Schörgendorfer, pers. comm.). Even so, it is hard to infer from written testimonials whether his decision to study archaeology can partly be accounted for by the political propaganda of the time before the rise of Nazism and by the political ideas that it may have inspired.

In the autumn semester of the academic year 1935/6, Schörgendorfer was enrolled at the Philosophical Faculty of the Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, the first Austrian university where the nationalistic Volkskunde scholarship flourished (Dow and Bockhorn Reference Dow and Bockhorn2004, 15–16). He also became involved in the local Catholic student fraternity CV-Verbindung Glückauf Graz, a part of the ‘Union of Catholic German Student Fraternities’ (Cartellverband) that was friendly to the Austrian fascist regime (Flouda, Pochmarski and Schindler Kaudelka Reference Flouda, Pochmarski, Schindler Kaudelka, Casari and Magnani2015, 97; Lenk Reference Lenk, Mitchell and Ehmer2015, 582); moreover, he distinguished himself academically. His supervisor, Professor Arnold Schober (1886–1959),Footnote 4 a member of the National Socialist Lecturers’ Association and of NSDAP since May 1938, singled out Schörgendorfer as one of his most gifted students, and encouraged him to follow an academic career (Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 202–3; Wlach Reference Wlach, Ash, Niess and Pils2010, 349, n. 27; 2014, 460–1). With this enthusiastic support, and owing to financial hardship, Schörgendorfer in January 1937 became the institute librarianFootnote 5 at the Department of Archaeology at Graz (Flouda, Pochmarski and Schindler Kaudelka Reference Flouda, Pochmarski, Schindler Kaudelka, Casari and Magnani2015, 96; Wlach Reference Wlach and Trinkl2014, 461 n. 51).Footnote 6 A four-month period of study leave from his duties, from 1 October 1937, until the end of January 1938, allowed Schörgendorfer to study at the University of Vienna (Fig. 2) as a visiting student (Flouda, Pochmarski and Schindler Kaudelka Reference Flouda, Pochmarski, Schindler Kaudelka, Casari and Magnani2015, 96). It was during this period that he volunteered for military service, as revealed by his own letter that is kept at the Austrian State Archives – Archive of the Republic. The long tradition of the University of Vienna in Germanic scholarship, expressed through the so-called Wiener Ritualisten cycle (Dow and Bockhorn Reference Dow and Bockhorn2004, 57–109), may have inspired him to enlist for duty prematurely.

Fig. 2. August Schörgendorfer wearing the Austrian folk costume as a visiting student in Vienna, 1937 (source: © Austrian State Archives 2008 – Archive of the Republic, file PA-Schörgendorfer, 27.01.1914).

On returning to Graz, Schörgendorfer was dismissed from his library post on 13 March 1938, namely just one day after the Federal State of Austria was annexed to the Nazi Third Reich. The fact that nearly all Austrian academics who had some connections to the authoritarian government or the Catholic church lost their jobs (Fleck Reference Fleck, Marks, Weindling and Wintour2011, 198), suggests that the reason for Schörgendorfer's dismissal was his membership of the Fatherland Front, which was considered as unacceptable by the new regime. Schörgendorfer's prior status as a ‘Senior’ of his Catholic student fraternity was also politically controversial in the new circumstances, because of the active engagement of most fraternity members against the National Socialists in the 1934 coup attempt against Dollfuss (Stitz Reference Stitz1970).Footnote 7 This new political reality left Schörgendorfer probably with no other option but to become a member of the Sturmabteilung (‘Assault Division’ or Storm Troopers, hence ‘SA’) in March 1938, as documented by his Military Service Card (Wehrstammkarte No. 563, Graz) (Fig. 3). Among the incentives for recruitment into the ‘SA’, the possibility to enter the officer ranks through the organisation must have had the greatest appeal to Schörgendorfer, who had a lower social background.Footnote 8 He did not participate in decision making or policy setting, though, since he belonged to one of the lowest ranks of the ‘SA’.Footnote 9 Like many members of the ‘SA’ who in 1938 joined the new army reserves and started training in order to become reserve officers (Campbell Reference Campbell1993, 663), Schörgendorfer passed the army recruitment test and enlisted in the Wehrbezirkskommando (Military District Command) Graz on 6 September 1938, as is suggested by his Military Service Card and his 1940 Curriculum Vitae.Footnote 10 He was assigned to the Ersatzreserve I, which consisted of all conscripts who had not completed their basic military service, with the specification that he should be called for duty a year afterwards.

Fig. 3. August Schörgendorfer's military identity card (Wehrstammkarte) (source: © Austrian State Archives 2008 – Archive of the Republic, file PA-Schörgendorfer, 27.01.1914).

Although his sense of revolutionary purpose impinged on his academic interests, his academic trajectory was not disrupted. In October 1938, Professor Schober ensured that Schörgendorfer was given a post as a scientific assistant at the University of Graz (Wlach Reference Wlach and Trinkl2014, 461 n. 52).Footnote 11 Building on an extensive handwritten essay on the topography of the Roman province of NoricumFootnote 12 he had written for the seminar of Rudolf Egger, the Professor of Roman History and Epigraphy at the University of Vienna (Wlach Reference Wlach2012, 80), he embarked upon systematic research on the Roman pottery of the eastern Alps region. For the needs of studying material in local collections he visited numerous sites, among which was Carnuntum, where the best-financed excavation project of the National Socialist era was undertaken under Hitler's aegis (Wlach Reference Wlach, Ash, Niess and Pils2010, 348; Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 82–4). He finally completed his extensive PhD dissertation under the supervision of Schober in Graz and graduated on 24 June 1939, as ‘Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Classical and prehistoric archaeology’. The thesis was published by the Austrian Archaeological Institute during the war in 1942 with the title Die römerzeitliche Keramik der Ostalpenländer. In the ‘Foreword’ of the book, Camillo Praschniker (1884–1949), also a former member of the Fatherland Front (Wlach Reference Wlach2012, 80 n. 50), addressed thanks to the military supervisors who granted the author leave in order to correct the manuscript. The study was well received (Behrens Reference Behrens1943, 334–5; also Goessler Reference Goessler1943, 774–9), and along with Eva von Bonis’ (Reference Bonis1942) book on the Roman province of Pannonia initiated the study of the Roman artefacts in association with the local Celtic culture (Schindler Kaudelka Reference Schindler Kaudelka, Erath, Lehner and Schwarz1997, 233, fig. 106; Wlach Reference Wlach and Trinkl2014, 461). Following a cultural-historical approach, Schörgendorfer grouped the 600 types of pottery vessels he studied from Noricum within an evolutionary scheme (R. L. 1946, 168–9). His interpretative narrative was built upon the historical continuity he deduced, and was also reinforced by his discussions of the Early Iron Age Hallstatt culture and the Late Iron Age La Tène culture. His ethnocentric argument on the continuation of burial in tumuli without interruption from the Hallstatt period to the Roman domination (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1942, 214–15) was notably criticised by the Dutch archaeologist H. van de Weerd (Reference Weerd1944). Schörgendorfer's focus on ethnicity and the presence of Celtic groups that can be inferred from material culture also seems to have its roots in Kossina's settlement-archaeology. However, his discussion did not reach the level of racial hierarchisation that serves as a criterion of a complete acceptance of National Socialist ideology (Altekamp Reference Altekamp2016, 23–5). Similar issues of ethnicity were still valid as a research question in the 1950s (Saria Reference Saria1950, 473), but recent developments in the field have reassessed the process of Romanisation in the region of the Eastern Alps under the light of acculturation (Stuppner Reference Stuppner2012).

Nonetheless, Schörgendorfer's research interests went far beyond the archaeology of the Roman provinces, since he was awarded the German Archaeological Institute's travel grant for the next academic year 1940/41, in order to visit Classical sites in Greece (Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 203, n. 41). However, preparations for the outbreak of World War II radically changed his agenda. He was finally called for service on 17 August 1939, as is demonstrated by his army passbook (Wehrstammbuch). All the same, he was possibly allowed to attend the 6th International Conference of Classical Archaeology in Berlin from 21 to 26 August 1939, organised by the German Archaeological Institute as a propaganda venue (see Bericht … 1939 [1940]). This is suggested from his personal copy of the guidebook to the official conference exhibition, Das Deutsche Archäologische Buch. Den Teilnehmern am VI. Internationalen Kongreß für Archäologie Berlin 1939, a review of the latest archaeological publications that was given to all conference participants (Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 90). Among the distinguished foreign archaeologists who had been invited directly by the German government (Kirsten Reference Kirsten1940, 328–44; Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 86–90 figs 21–3) was Spyridon Marinatos (1901–74), the influential General Director of Antiquities of Greece (1937–40), who represented the authoritarian Ioannis Metaxas administration; Marinatos’ presentation on the protection of monuments during wartime seems very prophetic in retrospect (Dyson Reference Dyson2006, 204; Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 90 fig. 24; Petrakos Reference Petrakos2013, 338).Footnote 13

After that point, we can follow Schörgendorfer's gradual advancement in military rank through his army passbook and the Curriculum Vitae he personally submitted in 1940, along with his application to the rank of officer. After entering active service in the Panzerjäger Ersatz-Abteilung 48 of Graz on 3 March 1940, and attending the academy for officers at Wünsdorf outside Berlin, as we learn from a letter by Arnold Schober,Footnote 14 Schörgendorfer was appointed as a candidate ‘reserve’ officer on 21 June 1940. He travelled also to Yugoslavia and Italy (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1942, IX), presumably before he presented himself to the corps after war broke out in September 1940. While he was in military service, he continued holding the post of Arnold Schober's academic assistant in the University of Graz (Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 206). His active involvement, though, in the ‘project for the collection and publication of all stone monuments in the eastern Alps lands’, initiated under the direction of Camillo Praschniker, was hampered by his continuing presence on the war front; in 1943 he was eventually replaced by Erna Diez.

On 26 October 1940, Schörgendorfer was finally sent to Norway and assigned to the anti-tank battalion Panzerabwehr-Abteilung 55 of the 2nd Mountain Division (2. Gebirgs-Division), which was used as an occupation force (Niebuhr Reference Niebuhr1941, 48–9). After he was upgraded to the rank of sergeant on 25 April 1941 (Fig. 4), and left northern Norway, we can follow his movement and archaeological activity through documents from the archive of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens, regarding the excavations on occupied Crete. This island was the last part of Greece to be affected by the war. ‘Operation Mercury’, an airborne invasion unprecedented in history, started on 20 May 1941 (Beevor Reference Beevor1991, 72–81; Richter Reference Richter2011). Among the numerous German military forces that finally seized the island after nine days of battle was a select infantry corps of alpinists, the 5th Mountain Division (5. Gebirgs-Division). This was led by the Austrian Major General Julius Alfred Ringel (1889–1967), who, with a reputation for ferocity, exerted control over central Crete and initiated the illegal archaeological excavations of the Wehrmacht at Knossos (Ringel Reference Ringel1994; Williamson Reference Williamson2005, 43–5). His antiquarian interest may have been rooted in an institutionalised respect of educated Austrians and Germans for aspects of ancient Greek culture (Marchand Reference Marchand1996). After a request by the acting Ephor of Cretan Antiquities Vasileios Theophanides,Footnote 15 Ringel notably donated to the Heraklion Archaeological Museum a fragment of a Minoan steatite conical rhyton depicting a peak sanctuary scene, which he had allegedly bought from a Cretan (Platon Reference Platon1951, 154–6 fig. 5). The fragment (HerMus. Inv. no. L2397) was joined in 1959 to another specimen found near the excavation of ‘Hogarth's Houses’ on Gypsades (Alexiou Reference Alexiou1959, 346, pls. LD–LE). A post-war report by the representative of the British School, Thomas Dunbabin (Reference Dunbabin1944, 86), which refers to small-scale illicit German excavations in the area of Gypsades, suggests that Ringel's fragment may have been recovered from these excavations.

Fig. 4. August Schörgendorfer wearing the ‘peaked cap’ and the ‘Wehrmacht eagle’ insignia, 1941 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Ringel was keen also on supporting the foundation of a Research Institute of Crete by the University of Graz because of his friendship with Arnold Schober (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 475; Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 204). In any case, this endeavour brought August Schörgendorfer to the fore, and also caused a dispute between the university, the German Archaeological Institute at Berlin and its Athens branch. Ringel met Professor Schober in July 1941 and reached a personal agreement with him (Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 204). The details are revealed by a letter of Schober (DAI Athens archive, Box K7 – old no. 43, 44, dated 30 October 1941). Schörgendorfer was accordingly assigned to an infantry regiment of the Wehrmacht, namely the Gebirgs-Panzerjäger-Abteilung 95 of the 5th Mountain Division. His task was to supervise on behalf of the University of Graz the excavations Ringel had already started at Knossos in the summer of 1941 (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 476). As deduced from his military documents, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in October 1941, and served on Crete from 14 October 1941 to 15 December 1942. A letter of reference by Schober to the commander of the Military District Division Graz (Austrian State Archives – Archive of the Republic/file PA-Schörgendorfer, 27.01.1914, letter of 15 November 1941) portrays him as

an aspiring, seriously committed person, whose first scientific work showed a marked talent. About his character and attitude nothing adverse is known to me. Regarding his social position and his economic standing I have to say that despite being impecunious, he has, as long as I have known him, lived in good conditions from personal earnings.

With these credentials, Schörgendorfer was, subsequently, summoned by Ringel as an officer of the military Referat Kunstschutz.

This special unit was founded shortly after Greece's occupation under the Supreme Commander of South Greece (Befehlshaber Südgriechenland), Eduard Wagner, as a group of the military administration of the Army High Command (Günther-Hornig Reference Günther-Hornig1958, 63–4; Petrakos Reference Petrakos2013, 323–4). Martin Schede, the director of the German Archaeological Institute at Berlin who initiated plans for excavations in Greece immediately after its occupation,Footnote 16 recommended specific archaeologists, conscripted to military service, as officers of the Kunstschutz (Hilller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 465, n. 8). Hans Ulrich von Schoenebeck (1904–44) was appointed as the chief of the Kunstschutz in April 1941 (Steimle Reference Steimle2002, 293 n. 11) and Wilhelm Kraiker (1899–1987) was assigned to it officially from 4 October 1941. From a letter of von Schoenebeck to the archaeology professor Andreas Rumpf (dated 4 July 1941), we learn that the former had personally dispatched Kraiker, so that he would function as a prospective military administrator after the reformation of the Kunstschutz (Petrakos Reference Petrakos1994, 117–18, 121, 124).Footnote 17 Kraiker, along with the archaeologists F. Brommer, W. Darsow and G. Kleiner, had also been suggested by von Schoenebeck as potential members of the aerial reconnaissance project of archaeological sites, initiated by the German Archaeological Institute (Petrakos Reference Petrakos1994, 119, 122–4).Footnote 18

The most important directive of the Kunstschutz was to protect antiquities and function as a link with the Archaeological Directorate of the Greek Ministry of Education. This was not a straightforward role, since the Kunstschutz was ideologically aligned with the German Archaeological Institute against the Special Command Force Prehistory of the Amt Rosenberg (Junker Reference Junker1998, 288). This particular office of the Nazi Party was headed by Hans Reinerth, the theorist of the reorganisation of German pre- and protohistoric archaeology according to the National Socialist dogma (Fröhlich Reference Fröhlich2008). Claiming exclusive competence over prehistoric archaeology (Hassmann Reference Hassmann2002, 78–83), the Amt Rosenberg undertook excavations in Greece at the beginning of the war with Lieutenant Hermann von Ingram at its head, without being subjected to control by any other German organisation (Hampe Reference Hampe1950, 8). Finally, thanks to the intervention of von Schoenebeck and of the Foreign Office (Petrakos Reference Petrakos1994, 119–20; Krumme Reference Krumme2012, 172), and possibly also due to an agreement with the SS-Ahnenerbe (Junker Reference Junker1998, 290), the Athens branch of the German Archaeological Institute was granted from September 1941 almost sole responsibility for undertaking and supervising excavations in occupied Greece. Walther Wrede (1893–1990), a high-ranking member of the NSDAP acting as the First Secretary of the Institute at Athens from April 1937 to 1944,Footnote 19 and Roland Hampe (1908–81), an assistant since 1936 and the official interpreter of the Wehrmacht towards the end of the German occupation (Hölscher Reference Hölscher1981, 621; Lullies and Schiering Reference Lullies and Schiering1988, 307–8), were obviously responsible for this change of politics.Footnote 20 In any case, this did not prevent casual problems arising from the interaction of the German Archaeological Institute with the Kunstschutz, as will emerge from the discussion of the latter's activity on Crete.

On 22 August, 1941, Ringel had undertaken the occupation of Sir Arthur Evans’ Villa Ariadne at Knossos, property of the British School at Athens, and used the villa as the headquarters of the 5th Mountain Division.Footnote 21 Taking advantage of the absence of the Knossos Curator, Richard W. Hutchinson, since April 1941 (Merrillees Reference Merrillees and Huxley2000, 34), Ringel selected an unspecified number of archaeological artefacts from the British School excavations and sent them to the University of Graz, thus fulfilling Schober's wish to enrich its Archaeological Collection. Schober himself in a letter to Wrede confessed: ‘My institute has no sherd from Crete at all and naturally I did not want to let this favourable opportunity go by’ (DAI Athens archive, Box K7 – old no. 43, 44, dated 30 October 1941).

Two unpublished reports submitted to the Greek Ministry of Education by the Ephor of Antiquities Nikolaos Platon and by Vasileios Theophanides via the Fortress-Division-Crete at Chania reveal hitherto unknown details regarding the confiscation, which preceded Schörgendorfer's appointment as an officer of the local Kunstschutz office.Footnote 22 In early September 1941, Ringel took the key from the local guard and opened a locked room near the Throne Room at the palace of Knossos, where the Stratigraphic Museum was based.Footnote 23 The Major General and some of his guards confiscated many objects in spite of the reaction of von Schoenebeck, who happened to be present. This is confirmed by another unpublished report by Platon (Heraklion Museum archive, document with protocol no.1567/1641) written on 11 December 1944, which attests that

eleven Minoan clay vases, a bronze hydria, a stone tripod vessel, 6–7 glass beads, a few sherds of ‘eggshell ware’ and a metal box containing small vases were stolen; only one wooden crate containing antiquities was returned.

The same report also specifies that not just pottery sherds, as previously reported by R. Hampe (Reference Hampe1950, 6: no. 8),Footnote 24 but also a number of antiquities from the Villa Ariadne, including a headless Roman statue, were airlifted to Graz (Works of art in Greece 1946, 25, prepared by Dunbabin, cf. Merrillees Reference Merrillees and Huxley2000, 36; Tiberios Reference Tiberios2013, 176, n. 54). A formal protest written in German on 12 September 1941, and addressed by Platon and Theophanides to Ringel (Heraklion Museum archive, document protocol no.1256/1375), throws some light also on the active opposition of the representatives of the Greek Archaeological Service to the occupation forces and to their compulsory cooperation with the Kunstschutz (Fig. 5):

Since, according to the great laws of archaeology, no object may be taken out of museums and collections without an official permit (by the Ministry), we ask you, Herr General, to give the necessary order, so that the aforementioned objects be shortly redisplayed at their place, especially given that they constitute an important collection.

Fig. 5. Letter by N. Platon and V. Theophanides to Major General J. Ringel (source: © Heraklion Museum archive/Department for the Administration of the Historical Archive of Antiquities and Restorations, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, document protocol no. 1256/1375 of 12.9.1941).

The Kunstschutz officers later tried to recall the objects back to Greece without success; some material was subsequently given by the Rector of the University of Graz to the Archaeological Institute (Christidis et al. Reference Christidis, Dourdoumas, Lehner, Lorenzutti, Morak, Neuhauser, Pochmarski and Müller2013, 232–3, Inv. Nos. G213–G232).Footnote 25 Recent attempts to identify and catalogue the material of the ‘Ringel collection’, which is now housed at the Universalmuseum Joanneum in Graz, confirm that the finds date from the Neolithic up to the Roman periods (Koiner and Lehner Reference Koiner and Lehner2015).Footnote 26

This violation of archaeological ethics by Ringel sanctioned the role of the Kunstschutz as a counterweight to the arbitrariness of the Major General. Nevertheless, in November 1941, Hans Ulrich von Schoenebeck announced to the Amt Rosenberg the official occupation of Villa Ariadne ‘in accordance with a request of the Sonderkommando Rosenberg in favour of the Reich’; the Führer would allegedly decide after the war who would ultimately own the villa (Fig. 6).Footnote 27 In the same month, Schörgendorfer (Fig. 7) and Ulf Jantzen (1909–2000), who had by then been dispatched to the commander of the Fortress-Division-Crete and served as the officer in charge of the Cretan Kunstschutz office,Footnote 28 were ordered by Ringel to excavate at Knossos (Fig. 8) (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 476 n. 69). From 27 October to 12 December 1941, they excavated part of a Roman house (20 × 20 m) above the north end of the Unexplored Mansion behind the Little Palace (Fig. 9) with a team of Greek captives.Footnote 29 Accordingly, Schörgendorfer submitted his first report to the Kunstschutz on 20 November 1941 (DAI Athens archive, Box 43, ‘3. Bericht über die Tätigkeit des Kunstschutzes in Iraklion’). Jantzen (Reference Jantzen1995, 494, pl. 98:3) later claimed that he developed a collegial relationship with his Greek colleagues. Still, the Greek Ministry of Education was officially informed of this illicit excavation on 29 November, 1941, by Platon (document prot. no. 1291/1395), who specified that ‘as orally stated by the excavators, the purpose of the excavation was to reveal Minoan buildings, which supposedly lie in the deeper strata’.Footnote 30

Fig. 6. Letter by H.U. von Schoenebeck to the Amt Rosenberg (source: © DAI Athens/D-DAI-ATH-K7-Villa Ariadne. All rights reserved).

Fig. 7. August Schörgendorfer as a Lieutenant of the Wehrmacht at Knossos, 1941 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 8. Schörgendorfer's photos of Villa Ariadne and the excavations at Knossos (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 9. The site of August Schörgendorfer's and Ulf Jantzen's excavation at Knossos, 1941 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Jantzen, who became the second post-war director of the German Archaeological Insitute in Athens after Emil Kunze (Fittschen Reference Fittschen2000, 1, 4), elaborated on the special circumstances of this excavation, explaining that both he and Schörgendorfer felt uneasy at digging a site which until then was the research territory of the British School at Athens (Jantzen Reference Jantzen1995, 494–5, pl. 99:3; for a different opinion see Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 95, n. 371). Thomas Dunbabin's post-war report confirms their claim that they intentionally did not penetrate deeper than the Roman stratum, in order to protect the site until Ringel should order them to stop (Dunbabin Reference Dunbabin1944, 86, n. 19, following a report by Nikolaos Platon). Nonetheless, a letter of protest by the Greek Minister of Education, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos, was sent to von Schoenebeck in early January 1942.Footnote 31 In a strict tone, the minister stressed that no application for an excavation permit had been made to the Ministry. He additionally requested that measures be taken so that the excavators respect the Greek archaeological law:

as specified by the latter, excavations are permitted to the foreign archaeological schools provided that an excavation permit of the Ministry is granted after the agreement of the Archaeological Council.

Ringel's excavation also caused the immediate reaction of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens. Wrede tried to manipulate the support of the Reich's Ministry of Education, which had supervised the German Archaeological Institute since 1934, for his cause (Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 60). His plan was to succeed in detaching the Classical archaeologist Gabriel Welter (1890–1954) from his military service in Aegina and sending him to Crete to ‘safeguard the urgent scientific German interests’, as he wrote to von Schoenebeck in November 1941 (DAI Athens archive, Bb.Nr./75/41, letter of 12 November 1941). Contrary to what has been claimed previously (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 464), Wrede's statement betrays that the strategic philosophy of the institute was not to reinforce archaeological ethics but to widen its sphere of influence by excavations in a new region:

The Institute has for its part an urgent cultural-political interest in beginning academic work on Crete, where up to now excavations have been conducted exclusively by the British, French, Italians and Greeks.

The case reminds us of the wider dispute between the German Archaeological Institute at Berlin, the Römisch-Germanische Kommission and the Amt Rosenberg for the control of excavations (Junker Reference Junker1998, 287–8; Halle Reference Halle2002, 447–8).

Wrede's request was not granted by the military commander of Aegina, because Welter was indispensable for the occupation of the island, and also had no particular interest in moving to Crete.Footnote 32 Accordingly, Friedrich Matz (‘the Junior’, 1890–1974) and von Schoenebeck were sent on a mission to Crete on 12 November 1941, in order to oversee and coordinate the excavation by Schörgendorfer and Jantzen.Footnote 33 Wrede reported to Schede that he himself would fly to Crete when the next opportunity for a flight arose. In this way, the German Archaeological Institute managed to impose its institutional control over the Wehrmacht excavations and even over the Kunstschutz representatives. Still, Platon could not personally supervise the excavation at Knossos, because Matz and Wrede – both adherents of the National Socialist status quo (Manderscheid Reference Manderscheid2010, 60 n. 138–40, 54–5) – on visiting it stated that the excavation was run by Ringel.Footnote 34 At any rate, according to Platon's 1944 report the excavation finds ‘were said to have mainly consisted of sherds and insignificant objects of the Roman era which were never handed over to the Heraklion Museum.’Footnote 35

Schörgendorfer's archaeological activity on Crete was meant to be institutionalised through a letter addressed by Bernhard Rust, the Minister of Education, to General Alexander Andrae (1888–1979), the commander of Fortress-Division-Crete (Foltmann and Möller-Witten Reference Foltmann and Möller-Witten1957, 173). The letter (DAI Athens archive, Box K7, ‘document WO 1535’, dated 26 January 1942) was also forwarded to the German Archaeological Institutes at Berlin and Athens, as well as to von Schoenebeck (Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 95 n. 373). It reveals that Rust personally urged Matz to go to Crete again in order ‘to examine the scientific prospects and conditions for a great German excavation’. The minister himself interestingly aspired for a new and great excavation target, and not for starting excavations at Knossos or Phaistos:

A precondition for this is that the archaeological specialists Dr Kirsten and Dr Schörgendorfer, who up to now have been assigned to me by the Wehrmacht in an obliging way, be available to us and that Dr Jantzen be again dispatched from his corps.

This also explains the involvement of the archaeologist Ernst Kirsten (1911–87), a corporal in the Luftwaffe and a member of the NSDAP since 1937 (Olshausen Reference Olshausen2014, 329–30), in the Kunstschutz projects on Crete from May 1942 to 1943. At the same time, Rust declared his support to Ringel through a letter to him by offering to finance the continuation of his excavation at Knossos.Footnote 36 It is unclear whether the minister was also indirectly supportive of Ringel's idea of a ‘Crete-Institute’ at the University of Graz. The rest of the correspondence between the Minister of Education Rust, Wrede, and the officers of the Kunstschutz rightly gives the impression that the latter primarily formed a closed club of archaeologists with scientific ambitions (Petrakos Reference Petrakos1994, 120–1). The degree to which Kirsten and Schörgendorfer were sympathetic to the aspirations for a ‘Crete-Institute’ at Graz cannot be inferred from the available archival evidence. A short article in the 18 March 1942 issue of Cottbuser Anzeiger shows that particular politicised circles were strongly supporting these plans:

For the first time in this war, a District Students’ Day was organised by the National Socialist German Students’ League for the students of the Styrian universities and colleges. The main theme of the scientific session was ‘Germany and the South East’. As announced, a Crete-Institute will be founded at the university. Excavations have already started on the island.

Kirsten himself, in his autobiography, makes only a passing mention of his important excavations on Crete (Kirsten Reference Kirsten1990, 106): ‘So … an involvement in the German protection of monuments in 1942 brought about the possibility of active archaeological excavation.’

THE EXCAVATIONS AT APESOKARI/MESARA

Following the legacy of Ringel, General Alexander Andrae founded in early 1942 a special Kunstschutz department within the ‘Group Interior Administration’ with Jantzen in charge.Footnote 37 From that moment onwards all relevant documents of the Greek Interior Administration were to be forwarded to it by the Athens-based Referat Kunstschutz. From 26 February to 18 April 1942, when Jantzen was again dispatched to the department, Schörgendorfer acted as the sole Kunstschutz officer in charge in Heraklion. The reports addressed by him to the Fortress-Division at Chania illustrate his manifold activities and his key role in documenting the state of the ancient monuments through frequent autopsies.Footnote 38 His main duties were the reinstallation, surveillance and safety of the museums at Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion, as well as the protection of the archaeological sites, the local collections, and the occasional finds discovered through building operations.

Schörgendorfer's responsibility is indicated also by the fact that he was charged by the German Archaeological Institute with submitting a proposal on excavation projects for the post-war era in the sense that Minister Rust had discussed. With his letter of 20 April 1942, he suggested the following projects: a systematic ‘Topography of Knossos exploration project’, the rescue excavation of the looted tholos tomb at Apesokari that he had already started, and test excavations at the sites of ancient Aptera and Chersonesos, as well as research in West Cretan sites, such as Monastiraki/Kharakas and Apodoulou/Gournes.Footnote 39 It is noteworthy that the last two sites had originally been traced by the archaeologist John Pendlebury in the 1930s, before he was summoned in June 1940 by the Military Intelligence – Research (hence ‘MI(R)’) in order to prepare future guerilla bands on Crete (Dunbabin Reference Dunbabin1947, 188; Hammond Reference Hammond, Hammond and Dunbabin1948, 50–1, 55–6, 58). The greatest emphasis, though, was placed by Schörgendorfer on a prospective excavation of the city of Knossos, which he described as

one of the most urgent and successful explorations which have to be undertaken by the German scientists, and which does not lie in the shadow of the surveys undertaken up to now by foreign schools.

Schörgendorfer's proposal was met with enthusiasm by Bernhard Rust, who stated that this kind of exploration initiated the potential for a new era of active archaeological engagement of the Institute on Crete (Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 95). Besides, the German Archaeological Institute was then financed by the Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt); therefore, it identified with the prevalent foreign policy of the Nazi regime (Jansen Reference Jansen2008, 164–6). Apparently, Schede, in a letter addressed to Wrede, also left the possibility open that in the post-war era Schörgendorfer and Fritz Schachermeyr (1895–1987), at that time a professor at the University of Graz, should engage in excavations on the island.Footnote 40 Schachermeyr's selection by the director of the German Archaeological Institute obviously aimed at satisfying the demands of an influential network; this consisted of professors Arnold Schober and Karl Polheim, the Rector of the University of Graz, as well as of Julius Ringel, who was associated with Minister Rust. On the other hand, Schachermeyr had been involved in research on east Crete since 1938 (Schachermeyr Reference Schachermeyr1938, 466–80). As a member of the NSDAP since 1933, he adhered to the dogma that Classical archaeology was obliged to serve as a valuable witness of ancient Nordic/Aryan studies (Schachermeyr Reference Schachermeyr1933, 593 n. 8; Chaniotis and Thaler Reference Chaniotis, Thaler, Eckhart, Sellin and Wolgast2006, 403). During his professorship at Graz, he not only lectured on racial-biological themes, but was also associated as a ‘free collaborator’ with the SS-Ahnenerbe, which financed some of his research travels to the Balkans (Pesditschek Reference Pesditschek2007, 55–6 n. 111, 58).

Despite the priorities set by Rust, Schörgendorfer's proposal, which was submitted to General Andrae through the Kunstschutz at the end of May 1942, was only partly accepted by Jantzen and Welter. The proposed excavation of Knossos was rejected by Jantzen as politically incorrect and potentially inconclusive, as suggested by his letter to the military authorities.Footnote 41 Schörgendorfer's interest in Knossos is further manifested by his photo of the supersized cuirassed statue of the Roman emperor Hadrian (Fig. 10), which is still on public display opposite the entrance to the Villa Ariadne (Karo Reference Karo1935, 241; Gergel Reference Gergel and Chapin2004, 372–3, 375 n. 30, 388 fig. 19:5). In any case, he was allowed to continue his study of the Knossos area, which did not depend on the potential of a prospective excavation there. For this reason, Jantzen demanded that Rudolf Stampfuss of the Amt Rosenberg return to Schörgendorfer the British topographical drawings he had confiscated from the library of the Villa Ariadne in the summer of 1941; there is no indication, however, whether these were ever returned. Still, it was particularly specified that Ernst Kirsten would carry out the topographical survey after his arrival.

Fig. 10. Cuirassed statue of the Roman emperor Hadrian opposite the entrance to the Villa Ariadne (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

After Welter was sent by Wrede to Crete despite his initial reservations,Footnote 42 he reported directly to the German Archaeological Institute at Berlin (DAI Athens archive, Box 7, ‘Lagebericht No. 1’, 1 August 1942). His first report reveals that Schörgendorfer had also personally applied to excavate the Roman site of Chersonesos from 1 August onwards, a research project more suitable to his specialisation. This application was not approved by Welter, who wanted Schörgendorfer to explore instead the settlement associated with the already excavated Tholos Tomb A at Apesokari. Welter's second and third reports highlight his instrumental role in aligning the excavation plans of General Andrae with the research interests of the German Archaeological Institute. In particular, he persuaded the General that all projects should be carried out under the authority of the Institute and not of the ‘Crete-Institute’ which the University of Graz strived to found (DAI Athens archive, Box 7, ‘Lagebericht No. 2’, 8 August 1942; also ‘Lagebericht No. 3’, 15 August 1942).

In the end, a project of small-scale excavations was agreed upon by General Andrae and the Institute, and Welter became the excavation coordinator (Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 95). Apparently, this was a violation of the previous German Archaeological Institute policy to ask for excavation permits from the Greek State. By August 1942, four excavations had already been initiated: Heinrich Drerup's excavation at Aptera in collaboration with Theophanides, the Greek Ephor of Chania, Jantzen's cave excavation at Koumarospilio on the Akrotiri peninsula, Kirsten's excavation at Apodoulou, Schörgendorfer's excavation at Apesokari, and Welter's excavation at Cape Spatha/Diktynnaion (Matz Reference Matz1951; Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr1952, 219–20). Moreover, Ernst Kirsten's and Kimon Grundmann's excavation at Monastiraki/Kharakas took place from 14 September to 10 October 1942 (Grundmann Reference Grundmann1951, 62; Kirsten Reference Kirsten1990, 66–7 n. 28). An article by Jantzen reported on these excavations in the local German language newspaper of the Wehrmacht, Veste Kreta, of 18 February 1943 (Merrillees Reference Merrillees and Huxley2000, 35–6).

The excavation of Tholos Tomb A at Apesokari was conducted by Schörgendorfer in the period from April to May, as shown by the ‘12th Report’ and ‘Anlage 1’ to the Fortress-Division-Crete submitted on 29 May 1942; it finished in August (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1951a, 13). Again, the representatives of the Institute justified this as a decision of General Andrae due to his wish to initiate an excavation project on behalf of the Kunstschutz (Vigener Reference Vigener2012a, 95). In his letter of 20 April, 1942, Schörgendorfer informed General Andrae that he had already started the excavation; he also planned to publish his findings in the Archäologischer Anzeiger issue of the same year. An unpublished report by E. Gavaletakis, the local Guard of Antiquities at Gortyn, submitted to the Greek Ministry of Education through the Ephor of Antiquities at Heraklion, clarifies that Schörgendorfer's excavation was carried out at the instigation of the president of the modern village at Apesokari, George Sifakis; it is also noted that the Guard was not allowed to supervise.Footnote 43

Schörgendorfer may also have read John Pendlebury's report that he had traced a Minoan settlement at Apesokari, where the latest interments of a tholos tomb had been partially looted by local tomb robbers (Pendlebury, Money-Coutts and Eccles Reference Pendlebury, Money-Coutts and Eccles1934, 88; Grundon Reference Grundon2007, 174). Pendlebury had visited the site in 1934 accompanied by Edith Eccles and Mercy Money-Coutts; both he and Money-Coutts photographed the site (Fig. 11). A classified document by George Anagnostopoulos, the Director of the Foreigners’ Centre at Piraeus, reveals that as a Kunstschutz officer, Schörgendorfer had access to German intelligence information originating from Pendlebury's confiscated personal archive on Greek private collectors, like Michael Eliadis (Grundon Reference Grundon2007, 51), the former British Consul on Crete.Footnote 44

Fig. 11. Photo of the looted Tholos Tomb A, 1934, captioned ‘Vigla above Apesokari (Mesara) near Platanos’ (source: © British School at Athens Archive, Mercy Money-Coutts Seiradakis Personal Papers, photo MCS-32 no. 290).

A more pragmatic explanation for the excavation may be inferred from the fact that a line of guarded German outposts was established along the southern coast of Crete in order to prevent the landing of British assistance to the Cretan resistance (Beevor Reference Beevor1991, 239). One of these outposts was based at Apesokari, not far from the excavation sites, as inferred from first-hand memories narrated by the villagers to the author and from a Word War II anti-aircraft vehicle still preserved as a memorial at the centre of the village. Therefore, the excavation at Apesokari may have also served to mask intelligence purposes. Information kindly supplied by local residents confirms the evidence deduced from Schörgendorfer's photo album, namely that the excavator appropriated for his stay the house of the teacher Michael Hassourakis, which still stands today at the south edge of the village (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1995, 475). One of the three consecutive sheets of photos, which deal with the excavation, depicts four staged photos of the archaeologist with the family of the house owner and Wehrmacht soldiers in the house's courtyard (Fig. 12). The same two soldiers (Fig. 13), as well as a local villager and his son, who are also depicted in the previous photos (Fig. 14), helped Schörgendorfer to excavate the burial chamber and the intact built annexes before the entrance of the tholos tomb (Fig. 15). The plan of the monument was drawn by the draughtsman of the German Institute at Athens, Nikolas Zografakis (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1951a, 13), and the excavation was visited by German military officers as well as by locals. Kirsten, Jantzen and Josef Foltmann (1887–1958), the military commander of the 164th Infantry Division of the Fortress-Division-Crete, on mules as well as the draughtsman and a local boy en route to the excavation, are depicted in one of the photos (Fig. 16). This visit most probably took place during the first of Kirsten's survey campaigns to south-central and south-west Crete from 20 to 31 May 1942 (Kirsten Reference Kirsten1951, 122–3, 132).

Fig. 12. August Schörgendorfer with the family of Michael Hassourakis at Apesokari, 1942 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 13. August Schörgendorfer wearing the Wehrmacht uniform and his team during the excavation of Tholos Tomb A at Apesokari, 1942 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 14. Local villager and boy who participated in Schörgendorfer's excavation of Tholos Tomb A at Apesokari, 1942 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 15. View of the Tholos Tomb A Annex from the east – Apesokari, 1942 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 16. Local boy, Ernst Kirsten, Ulf Jantzen, Nikolas Zografakis (?) and Josef Foltmann on a visit to the Apesokari excavations, 1942 (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Schörgendorfer also excavated a part of the Minoan settlement on Vigla Hill in September 1942. Despite the small scale of the project, the Greek daily newspaper Cretan Herald, which served as a medium of German propaganda (Skalidakis, Reference Skalidakisforthcoming), tried in February 1943 to generate publicity for this and other excavations of the Kunstschutz. An extended report on the tomb finds by Schörgendorfer was finally published in 1951 in the collective volume Forschungen auf Kreta 1942, commissioned by the military authorities and edited by F. Matz from 1945 to 1951 (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1951a, 13–22).Footnote 45 A preliminary report on the settlement was also included therein, but contained no photos or drawings of any finds, and created more puzzles than it solved (Schörgendorfer Reference Schörgendorfer1951b, 23–6). In two so far unpublished reports, Nikolaos Platon comments upon the professional care with which Schörgendorfer conducted the excavation of the Minoan settlement; he also specifies that Schörgendorfer was in constant communication with him and that after the end of the excavation he handed over all finds to the Heraklion Museum.Footnote 46

Following the publication of the two preliminary reports on Apesokari in 1951, only the 25 stone vessels from the tomb were inventoried in the Heraklion Museum Catalogue by Platon himself and formed part of the so-called Scientific Collection. When the majority of the finds mentioned by Platon were rediscovered in 2010, collectively labelled as ‘of unknown provenance – probably from a German excavation’, they were inevitably connected to Schörgendorfer's excavations, since all finds recovered during the occupation from the excavations in west Crete and the Amari valley were deposited in the Chania Museum. A few paper notes found in specific boxes proved essential in identifying the relevant material as provenanced mainly from the Apesokari settlement and in pinpointing the exact findspots. They are written in the Old German calligraphic (Sütterlin) handwriting of Schörgendorfer himself, as demonstrated also in his early manuscripts and by the captions on his photo album. Subsequent study of the finds has confirmed Platon's view that Schörgendorfer was a careful excavator. He paid close attention to the empirical data and, remarkably for his era, took the trouble to collect all sorts of archaeological finds, including skeletal remains, shells and a pumice stone (Flouda Reference Flouda2011, Reference Flouda2014). His two reports also reveal that he had achieved a quite thorough understanding of his Minoan material, which he tried to approach through issues of architecture, chronological classification and typology of the material artefacts, and without applying any National Socialist ideas.

SCHÖRGENDORFER'S TRAVELS ON CRETE AND BEYOND: 1942–4

Schörgendorfer's service for the Referat Kunstschutz also entailed travels around Crete, as his tasks included the inspection of excavations as well as the protection of archaeological finds and of historical monuments from German soldiers or others. The photos in his photo album were arranged by the archaeologist in a thematic sequence and, possibly, according to chronological order. This fact allows the possibility of building a narrative of Schörgendorfer's tours around the Heraklion, Chania and Lasithi prefectures. His itineraries are introduced through a photo shot from the aeroplane during his arrival on Crete (Fig. 1). Most of the following photos record the monuments for the needs of his Kunstschutz service. Nevertheless, the ethnographic value of many shots lies specifically in the fact that they document not only sites and persons related to military matters or archaeological sites, but also towns and landscapes, which have rapidly changed ever since. An intriguing parallel is offered by the numerous photographs and sketches of monuments and the Cretan landscape made by Private Rudo Schwarz, a German artist who served on Crete in 1943 as a Wehrmacht soldier and who kept also a Cretan Diary (Mamalakis and Mitsotaki Reference Mamalakis and Mitsotaki2010, 5–7).

In contrast, few of Schörgendorfer's photos were annotated by the archaeologist himself on their reverse side, allowing us to easily recognise the topographical context. With the eye of a specialist who is interested in architecture, Schörgendorfer has taken snapshots of important cultural heritage monuments of the Venetian period, such as the walls (Fig. 17), the Morosini fountain and Saint Mark's Basilica in Heraklion. One of the photos features Chersonesos, the site of one of his autopsies in central Crete, as evidenced by one of his Kunstschutz reports. Architectural landmarks, such as the monastery of Gonia, near Kolymbari, as well as the Byzantine church at the entrance of Saint John the Hermit's cave (Faure Reference Faure1958, 498), near Marathokefala, depicted on two successive pages of the photo album, most probably reflect a travel itinerary Schörgendorfer made through west Crete from 11 to 21 May 1942 (DAI Athens archive, Box 43, ‘12. Bericht über die Tätigkeit des Kunstschutzes auf der Insel Kreta’, dated 29 May 1942, and also ‘Anlage 1’). Popular landmarks and mnemotopoi – locales evoking the collective memory of a particular social group (Assmann Reference Assmann1992), in this case the German occupying forces – are also represented: the colossal ‘German bird’ (Fig. 18), a memorial built at the German war cemetery at Maleme, near Chania, and a distant view of the village of Kandanos, which was totally annihilated in 1941 by the Germans as an act of reprisal. In other cases, further archival research is needed in order to verify our speculations with regard to the location or the persons involved. For example, in one of the photos a group of soldiers pose in front of what should be the building of the Archaeological Collection in Hierapetra, by then the archaeological warehouse of the Italian occupation force, which Schörgendorfer inspected on 9 March 1942.

Fig. 17. Schörgendorfer's photo of the south-east part of the Venetian fortification, Heraklion (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

Fig. 18. Schörgendorfer's photo of the colossal ‘German bird’ (source: © A. Schörgendorfer's photo album, author's archive).

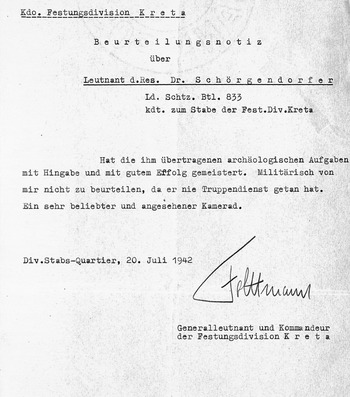

Despite Schörgendorfer's valuable service for the Kunstschutz, a formal request by him to prolong his stay on Crete was rejected by Josef Foltmann, the commander of the Fortress-Division-Crete, ‘because he had not done active military service so far’ (Fig. 19). On 15 December 1942 Schörgendorfer was transferred to the 3rd Mountain Division and sent to the Gebirgs-Panzerjäger-Ersatz-Abteilung 48, which was stationed in Cilli (Celje) in modern Slovenia (see Wehrstammbuch; Christidis et al. Reference Christidis, Dourdoumas, Lehner, Lorenzutti, Morak, Neuhauser, Pochmarski and Müller2013, 232 n. 40). Moreover, from 1 March until 14 October 1943, when he was seriously injured, he had to serve on the southern sector of the Russian front (Mius-Donez, Donez and Dnjepr) with the Panzerjäger Abteilung 335 (see Wehrstammbuch). On 14 December 1943, he was finally transferred to the Panzerjäger-Ersatz- und Ausbildungs-Abteilung 5 near Karlsruhe. For his military achievement, he was awarded the Iron Cross (2nd class) medal and two other badges of honour (Sturmabzeichen and Verwundetenabzeichen in schwarz).

Fig. 19. Document of the military commander of the Fortress-Division-Crete, Josef Foltmann (source: © Austrian State Archives 2008 – Archive of the Republic, file PA-Schörgendorfer, 27.01.1914).

Despite his period of active service and injury, his continuing preoccupation with Minoan archaeology after he left Crete is indicated by the submission of his Habilitationschrift thesis, entitled ‘Die Rundgräber des minoischen Kreta’, in May 1944 (Lehner Reference Lehner1998, n. 18). It was awarded on 7 July 1944 by the Rector Karl Polheim. This unpublished 100-page study, a copy of which is kept at the University of Graz, suggests that Schörgendorfer had personally visited the Mesara tholoi which he discusses. It also attests to his deep understanding of the subject. Unfortunately, he specifically refrained from giving any additional details on his excavation of Apesokari Tholos Tomb A, thus making a fresh look at the site inevitable (Flouda Reference Flouda2011; Reference Flouda2014).

THE END OF THE WAR AND THE DENAZIFICATION PROCESS

At the end of the war Schörgendorfer was interrogated by British forces while stationed at Graz, as the region of Styria was within the British zone of the Four Power occupation, which began in the summer of 1945 (Bader Reference Bader1966, Introduction).Footnote 47 The British Civil Censorship seal impressed upon the photos included in his Cretan photo album reveals that he was carrying them with him at that point. A stamp on his Wehrstammbuch, which states ‘dismissed by the British Military Government on 15.11.1945’ (file no. 1684)’, also reveals that he was released by the British Military Government as a prisoner of war on 15 November 1945.

He had also to suffer the political consequences. The specific circumstances that led to him being deprived of his institutional affiliation in 1945 and of his Habilitation title in 1948 are particularly obscure, as he never became a member of the NSDAP (Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 209–10). More archival work is needed in order to deduce whether it was a side-effect of intra-university rivalries or a result of the denazification process at the University of Graz. Besides, Schober, Schachermeyr and two thirds of the teaching personnel were dismissed by the university in 1945 (Pesditschek Reference Pesditschek2007, 59; Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 207–8). In any case, after Schörgendorfer's contract with the university expired on 30 November, it was not renewed by the office of the dean (Mindler Reference Mindler, Schübl and Heppner2011, 206, 209 n. 80). Unable to continue with his archaeological career, Schörgendorfer started anew as a tax advisor in Ried im Innkreis, where he lived until his death in 1976.

In general terms, differences in the denazification procedures followed in Austria and Germany have already been the focus of scholarly discussion (Arnold and Hassmann Reference Arnold, Hassmann, Kohl and Fawcett1995, 75; Altekamp Reference Altekamp2016, 46–7), and should be further explored in future studies.Footnote 48 In the framework of this study, it should be stressed that Schachermeyr and the rest of the Cretan Kunstschutz unit, such as Kraiker and Kirsten, who had adhered to the nationalist ideology and were members of the NSDAP, managed to have very successful careers after the end of the war (Pesditschek Reference Pesditschek2007, 62; Chaniotis and Thaler Reference Chaniotis, Thaler, Eckhart, Sellin and Wolgast2006, 401–2, 404–5, 412, table 1).Footnote 49

ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE WAR ZONE: IMPLICATIONS

Archaeology of the recent past has to do justice to events that are still lived as a collective trauma in the present (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2008, 251), and the period of World War II is no exception. Critical discourses on the connection between politics and culture have reiterated the fact that in order to approach past scholars of the humanities we need to develop an understanding of their social and scientific context. I have therefore striven to reconstruct Schörgendorfer's biography without overlooking the social networks and institutional structures in which his actions were embedded. The evidence presented here on his political background and activity demonstrates that he was fully enmeshed within both the ideological turmoil of Austria's fascism and also his own academic ambition. His early alignment with the totalitarian regime of the Fatherland Front and his formative experiences in his Catholic student fraternity indicate that he adhered to the extreme-right patriotic ideology promoted by chancellor Dollfuss. Naturally, after 1933, affiliation with the regime was one of the repressive mechanisms for academics and students alike, who were otherwise threatened with exclusion from the universities (Lenk Reference Lenk, Mitchell and Ehmer2015, 583). Nevertheless, Schörgendorfer's involvement in the paramilitary ‘SA’ of the NSDAP from March 1938 suggests his conformity with the National Socialist regime, despite its ideological differences from the Austrian fascist agenda. Like many German historians of this era,Footnote 50 Schörgendorfer's opportunistic attitude may have led him to follow the current trend in pursuit of his dream of individual achievement. This dream also laid the path to his military career and his participation in excavation projects in Crete. Even so, Schörgendorfer's wish to volunteer for the army at an early stage of his doctoral research clearly manifests his activism. Although it contrasts with the eagerness of prominent American archaeologists and philologists, such as Henry B. Dewing, Carl W. Blegen, and Bert Hodge Hill, to be involved in a political emergency by serving as members of the American Red Cross mission to Greece in the 1920s (Davis Reference Davis, Davis and Vogeikoff-Brogan2013, 18), it was also motivated by genuine and strong political commitment.

My effort to assess whether Schörgendorfer's archaeological interpretations were also affected by the National Socialist ideology is limited to his dissertation and his two preliminary excavation reports. As a doctoral student Schörgendorfer demonstrated careerism, mostly through his attachment to Professor Schober, who had clearly aligned himself with the National Socialist apparatus. However, although Schober's theories for the evolution of the art had a racial colouring (Wlach Reference Wlach and Trinkl2014, 464), Schörgendorfer's doctoral thesis is only minimally infiltrated with such ideas. The academic value of his study today lies in the fact that although it reflects an ethnocentric view, it deviates from the narrative of ‘Germanic’ nation-building imposed by National Socialism, such as the one connected with the Late La Téne period by the archaeologists W. Buttler and H. Schleif (Reference Buttler and Schleif1939) (see Arnold Reference Arnold2006, 19).

Schörgendorfer's incentive to excavate an important Minoan site may possibly be connected to an understanding of the Minoan culture as representing the ‘authentic past for Europe’. This paradigm was introduced by Arthur Evans (Preziosi Reference Preziosi and Hamilakis2002, 32; Hamilakis and Momigliano Reference Hamilakis, Momigliano, Hamilakis and Momigliano2006, 25–6) and later enhanced and manipulated by Nazi rhetoric. Nonetheless, the two papers by Schörgendorfer on the excavations at Apesokari do not offer any insights on how he personally perceived the Minoan past or his views on the ethnic identity or cultural uniqueness of the Minoans. Indeed, they do not demonstrate his personal adherence to racial discourses, such as Siegfried Fuchs’ diffusionist suggestion that ancient Greek culture developed from the Corded Ware of the Germanic heartland (Vigener Reference Vigener2012b, 224). Schörgendorfer's attitude is, therefore, in marked contrast to the earliest archaeological treatises of Fritz Schachermeyr, who followed the racial classification introduced by the racist eugenicist Hans F.K. Günther (Reference Günther1929a; Reference Günther1929b). In his discussion of the ‘racial position of the Minoan culture’, Schachermeyr (Reference Schachermeyr1939) assigned the Minoans to the Mediterranean race, which was distinguished from the superior Nordic/Germanic race (Bichler Reference Bichler2010, 83–5), and drew sharp criticism from F. Matz (Reference Matz1941, 346–50).Footnote 51 However, it cannot be inferred whether Matz himself, who edited the essays of Schörgendorfer and the other excavators in the post-war volume Forschugen auf Kreta 1942, should be held responsible for ‘purging’ the texts of the National Socialist directives.

With regard to issues of archaeological practice, Schörgendorfer did not use forced labourers at Apesokari, as his photographic record suggests. Except for a few photos with a political dimension, his photo album mostly offers a romanticised visual narrative through its focus on archaeological sites and the Cretan rural landscape. The omission of war themes by the photographer–annotator captures his detached emotional reality during his presence on Crete and, in my opinion, transcends the colonial – non-colonial dichotomy. Therefore, the photo album should be further studied as a ‘mnemonic trace’ of the events experienced by Schörgendorfer that was meant to engender active remembering and forgetting (Carabott, Hamilakis and Papargyriou Reference Carabott, Hamilakis, Papargyriou, Carabott and Papargyriou2015, 10–11).

On the other hand, the loss of Schörgendorfer's excavation notebook or notes, possibly during his period of active military service, and the concomitant result of the separation of his excavation finds from their stratigraphic setting, make their re-contextualisation an imperative. In any case, the appreciation of the Ephor of Cretan Antiquities, Nikolaos Platon, for Schörgendorfer's archaeological work and the fact that the latter handed over all finds from his personal excavations in the Mesara to the Heraklion Museum show that he paid due respect to archaeological ethics. Evidently, his name does not appear in the Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU) Reports and the ALIU Red Flag Names List and Index, issued by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), as the names of von Schoenebeck, Kraiker and Kirsten do.Footnote 52