1. INTRODUCTION: GREECE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE IMPERIAL PERIOD

The new power system established by Augustus after his victory at Actium (31 bc) changed the form of the ancient world in many different ways. The Roman state, expanding from Britain to Mesopotamia, included regions of different cultures, histories, social systems and organisations. The various ways in which the establishment of this new system affected life in the different regions of the empire is an issue which still causes a great deal of discussion among historians and archaeologists, mostly due to its similarity to modern phenomena like globalisation or imperialism (Hingley Reference Hingley2000). Modern research has tried, through different (and often alternative) approaches, to redefine the term Romanisation and reinterpret the political, cultural and ideological phenomenon of the Roman empire (Hingley Reference Hingley, Webster and Cooper1994, 41; Freeman Reference Freeman1993, 438–45; Woolf Reference Woolf1998, 1–23). Acculturation (Mitchell Reference Mitchell, Mitchell and Greatrex2000, 17–50), resistance (Dommelen Reference Dommelen, Laurence and Berry1998, 25–48) or even creolisation (Webster Reference Webster2001, 209–25) have quite often been used as alternative terms in order to define a very specific process, that of the incorporation of independent communities, city states, kingdoms and people into the Roman state, especially at the end of the first century bc, when it was transformed into the mild autocratic system that today is referred to as the Roman empire. Research has gradually started to focus not only on the different ways in which local societies reacted to this new socio-cultural reality, but also on the various ways in which Roman principles adapted to, and were shaped by, local situations. As a consequence, a new view of the Roman world has sprung up, in which diversity rather than homogeneity played the most important role.

Contrary to the old scholarly idea of a Greece that was left unaffected by any external influence, modern research has managed to show that incorporation into the Roman empire was a process which affected local Greek societies on many levels and in different ways (Alcock Reference Alcock1993). The early years of conquest, with the presence of large armies and the often quite destructive impact of Roman power (e.g. the destruction of Corinth), must surely have been dramatic for many Greek cities and towns. This, among other factors, must have led to a level of decadence, which, as shown by field surveys (at least in south Greece), is manifested in rural and urban decline (Bintliff Reference Bintliff2012, 313–18). It was only after the establishment of the Augustan regime that a new reality started to emerge, to the creation of which many different elements (nostalgia, archaism, conservatism, rediscovery of the past) contributed equally. In this context, a hybrid culture gradually prevailed, in the formation of which elements from both Greek and Roman material culture contributed reciprocally (Millar Reference Millar and Hansen1993, 238).

As in previous periods, urban life and the institution of the city continued to play a fundamental role in social structure. Cities, as the main theatre of action (then as now) of different institutions, persons and social groups, are not static entities but contain a dynamic aspect, which is best reflected in the development of their public spaces.

A new theoretical framework for the study of space, as proposed by B. Hillier and J. Hanson (Reference Hillier and Hanson1984), includes the revolutionary idea that society and space were not simply interrelated, but were similar concepts. The way that buildings are placed in space, their relationships as well as their architectural contexts, reflect the processes and the elements that shape society. In archaeology the social logic of space has been applied in the study of public spaces as a means to understand deeper changes in the structure of ancient societies. Since as early as the 1950s, when R. Martin published his study of the development of the Greek agora (Martin Reference Martin1951), it has become evident that the multifunctional centre of the ancient city was something more than just a public space. As noted by J.B. Jackson (Reference Jackson1984), the agora was the place where social hierarchy, social networks and relationships were reflected in the most dramatic way. Thus, the study of its development during a period in which the Greek world underwent a series of changes can prove to be very important in our attempt to understand the process of the incorporation of the cities of Greece into a political and cultural entity, which for the first time became transregional.

As previously demonstrated in depth (Evangelidis Reference Evangelidis2010), the agora of the ancient Greek city during the Imperial period was not left unaffected by this process, but it developed in a variety of ways towards a new kind of monumental public space. It is clear that as in every living city, past and present, the renovation of public spaces (modernisation, enhancement of infrastructure, monumentality) is a process inherently connected to the functionality and public image of the city. Although Roman presence – as an external power that replaced the civic autonomy of the Greek cities – had already been established in Greece since the mid-second century bc, the disturbance, the political unrest and the financial difficulties that the civil wars brought about made the undertaking of public works in the cities very difficult. Only after the victory of Augustus and the restoration of order can we trace the first clear attempts at urban development through great public works – attempts that continued very hesitantly during the first century ad and had reached a peak by the end of the first and beginning of the second century ad, when Greece became the focal point of Hadrianic and (later) Antonine imperial propaganda. Certainly the embellishment or modernisation of the cities was by no means a homogeneous process, but one that depended on a variety of factors, such as the political and financial status of each city (Rizakis Reference Rizakis and Alcock1997), the ability to attract great donors or imperial interest and the activity of the members of the local elites who, as donors and builders, enhanced their public image as pillars of social coherence and representatives of Roman authority. From the small provincial island city of Thera to cosmopolitan Athens, almost every city that managed to survive the difficulties of the first century bc and the transition to the imperial system tried gradually during the first and second centuries ad to renovate the urban landscape of the agora and its surroundings.

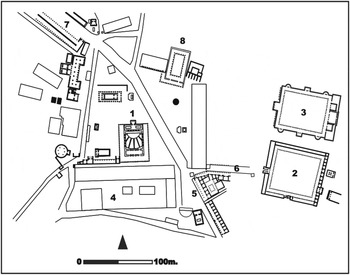

The developments in the organisation of space and architecture that will be presented in the following pages are based on research (Evangelidis Reference Evangelidis2010) which has taken into account archaeological and textual evidence from a number of sites (situated on the territory of the modern Greek state) where systematic excavation (at Athens, Argos, Thera, Thessaloniki, Mantinea, Thasos, Sparta, Corinth, Dion, Philippi, Patras, Knossos) has provided a more or less complete view of the development of their main public spaces during the Roman period (late first century bc – third century ad), as well as from a number of other sites where evidence is more fragmentary (Fig. 1). Although important, particular aspects of the development of public space, such as the establishment of imperial cult, the will of the local elites to promote themselves through the donation of public works and the transformation of many agoras to a memorial space through the careful reconstruction of the past, will not be discussed here, as they are outside the scope of the article.

Fig. 1. Sites mentioned in the text.

2. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PLANNING AND ORGANISATION OF SPACE

The organisation scheme of the early and classical agora was magnificent in its simplicity: an open space, usually located in the centre of the city, dotted with small shrines or ancestral monuments and surrounded by civic and religious buildings (Hölscher Reference Hölscher1998). Monumental architecture played only a secondary role to the central open space, where many of the daily religious, civic and commercial activities took place. The urban landscape was organised according to this basic spatial plan until the Hellenistic period, when, in many of the great cities of the Greek-speaking east, the agora started to be transformed into an architecturally defined monumental space, following developments in contemporary architecture (Hesberg Reference Hesberg1990, 231–41).

The concept of treating public space as a single architectural unit (the Ionian agora) was applied (Coulton Reference Coulton1976, 173) in many of the Greek cities that were founded or renovated during the fourth century bc, like Pella in Macedonia – which might actually have been one of the leading examples of this style (Hoff Reference Hoff1988, 248–50) – or Tegea in the Peloponnese, the agora of which was described by Pausanias (8.48.1) as having the rectangular shape of a πλίνθος. For many others, however, the transformation of the old open court to an ‘enclosed’ space was a process that remained incomplete until the beginning of the Imperial period. In the agoras of Thasos, Mantinea, Athens, Gortyna (Crete), Hierapytna, Corcyra, Maroneia, Thessaloniki, Thebes and many other large or small cities and towns the addition of a three- to four-sided portico or of free-standing buildings with columnar facades around a central court became the basic spatial organisation scheme in the Roman period. New finds, such as the portico (late first century bc) found in the area of the agora of the small Macedonian city of Kalindoia (Sismanidis Reference Sismanidis2006, 249–62) or the small tetrastoon (late first century bc) found in modern Stratoni (possibly ancient Stratonike) in Eastern Chalkidiki (Trakasopoulou and Papastathis Reference Trakasopoulou, Papastathis and Giannikouri2011, 239 ff.), indicate that the scheme was adopted by many cities of various sizes all over Greece. Elis, with its asymmetrically placed free-standing buildings, such as the stoa of the Corcyreans or the stoa of the Hellanodikai that made such a vivid impression on Pausanias,Footnote 1 is an indication that the application of this spatial scheme was clearly not a panacea for every city. The archaeological evidence seems to verify the description of Pausanias (Mitsopoulos-Leon Reference Mitsopoulos-Leon and Mitsopoulos-Leon1998, 182–5). The agora of Elis in the Roman period kept its older, more haphazard form of spatial organisation, something which probably emphasised the traditional character of the place as a training ground for horses destined to compete in the Olympic Games.

With the exception of Roman colonies, the most archetypical spatial feature of Roman urban design, the presence of an axially placed central building (usually a temple), is rare. Unique, of course, is the case of Athens, where the Odeion of Agrippa (Fig. 2. no. 1), an enormous roofed theatre that exceeded in height all other buildings in the Agora, occupied the largest area of the central square and provided a spectacular vista for all visitors entering the space through the northern entrances. H.A. Thompson (Reference Thompson, MacReady and Thompson1987, 7–9) argued that the Odeion of Agrippa in Athens played a similar role to the central Roman temple as a ‘temple’ dedicated to philosophy and arts. By contrast, T.L. Shear (Reference Shear1981, 361) saw the construction of the enormous odeion and also the transfer of the Classical temple of Ares to the centre of the Agora as a clear attempt to downgrade the site of the Agora as an assembly point for the citizens (contra Dickenson Reference Dickenson and Giannikouri2011, 50). It is undeniable that such a dramatic intervention in the spatial organisation of the Agora is open to many different explanations. A conscious attempt on the part of the central authority to emphasise the loss of the political autonomy of the city (Shear Reference Shear1981, 361), influence from Augustan Rome (Thompson Reference Thompson, MacReady and Thompson1987, 7–9; Walker Reference Walker, Hoff and Rotroff1997, 72), the transformation of the site into a memorial space (Alcock Reference Alcock2002, 53–4), or simply the result of a building programme that exploited every inch of an already overcrowded space are some of the different theories developed. Although Thompson's proposal is tempting, in reality there are no sound data to support the theory that the Athenians or the imperial patron of the building deliberately followed a Roman spatial scheme. It is, however, clear that the addition of the building in an iconic position in the centre of the Athenian Agora, which is also evident in other monuments and buildings of the Augustan programme, such as the monopteros on the Acropolis (Kavaja Reference Kavaja and Salomies1999, 88), marks a radical change in the traditional character of the old space, a change that was undeniably an immediate result of the incorporation of the city into the Roman empire.

Fig. 2. The Agora of Athens in the second century ad. 1 Odeion of Agrippa, 2 Agora of Caesar and Augustus, 3 Library of Hadrian, 4 South Square, 5 Library of Pantainos, 6 Colonnaded street connecting main Agora with Agora of Caesar and Augustus, 7 Long stoas framing the Panathenaic street, 8 Roman basilica.

Two Early Imperial temples held a central position in the organisation scheme of the agora of Mantinea (Fig. 3), a city that throve in the Early Imperial period due to its commitment to the Augustan cause during the power struggle. There, behind the skene of a large theatre that dominated the west side of an elongated agora (surrounded by an L-shaped portico), the foundations of what seems to be a pair of twin temples were discovered. G. Fougères (Reference Fougères1890, 252–4) proposed that the remains belonged to the temples (ναοὺς) mentioned in a long dedicatory inscription (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1913, no. 268), which lists the donations made by a couple of local notables (Euphrosynos and Epigone) who undertook the renovation of the agora at the time of Augustus. Besides the temples the programme included the construction of a large exedra (ἐξέδρα), a lavishly built makellos (μάκελλος), dining halls (δειπνιστήρια), public offices (ταμεῖα) and a building named βαίτης, which probably indicates the existence of a heating system. It is unknown which deities were worshipped in the temples since the cult is not mentioned in the inscription. However, a passage of Pausanias,Footnote 2 describing the agora of Sparta, might provide an indication of the nature of the cult. The temples of Augustus and Caesar in the Spartan agora were probably built early in the Imperial period (Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth1992, 127–8). Their type and position remain unknown but they are likely to have been twin temples (Clinton Reference Clinton, Hoff and Rotroff1997, 161–83: Eleusis) or a temple with a double cella (Thompson Reference Thompson1966, 171–87: stoa of Eleutherios Zeus, Athens), and to have occupied a prominent position. Mantinea and Sparta shared a special bond as the sole supporters of the Augustan cause in the Peloponnese during the fight against Anthony (Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth1992, 99) and therefore the connection of the Mantinean temples with the imperial cult is not impossible. Undoubtedly, the placement of the temples cannot be coincidental, and indicates the important position of the deities of the temples in the religious landscape of the city. Although Mantinea offers a unique case study for the development of a medium-sized city during the Imperial period, the only available evidence comes mostly from the old reports of Fougères (Reference Fougères1890). These reports do not provide much information about the architecture of the site or the succession of the different phases, and therefore should be treated cautiously.

Fig. 3. The agora of Mantinea during the Roman period.

Thessaloniki, the provincial capital of the Roman province of Macedonia, reached a peak during the Early Imperial period, and after the late first century ad its urban landscape was enriched by a series of monumental buildings, among them a new agora. The complex (Fig. 4), the impressive remains of which still dominate the centre of the modern city, started being built during the Antonine period, when an enormous three-sided portico surrounded an oblong square with dimensions of 146 × 97 m (Adam-Veleni Reference Adam-Veleni and Adam-Veleni2001, 15–38; Reference Adam-Veleni and Grammenos2003, 121–76). Large public buildings, among them an archive, a mint and an elaborate odeion, were found behind the east stoa, while a large double cryptoporticus supported the south stoa of the complex (Adam-Veleni Reference Adam-Veleni and Lane Fox2011, 556). Archaeological research in the centre of modern Thessaloniki has provided evidence that the agora was part of a monumental civic centre, which extended in successive terraces from the lower level of the via Regia (main decumanus) in the south to the rockier and steeper area in the north, where the Basilica of St Demetrius was later built. Archaeological and textual evidence shows that the area south of the agora might also have held monumental buildings, such as the Chalkeutike Stoa (Stoa of the Coppersmiths) or complexes such as the Gymnasion-Bath to which the monumental facade known as ‘Las Incatandas’ (The Enchanted) possibly belonged (Adam-Veleni Reference Adam-Veleni and Lane Fox2011, 557).

Fig. 4. The agora of Thessaloniki (source: Stefanidou-Tiveriou Reference Stefanidou-Tiveriou2001, 404 fig. 13).

The north side of the agora opened towards a raised terrace (separated from the agora by one of the decumani of the city), which originally was thought to have supported the stadium. The excavations revealed two important buildings of Roman Thesssaloniki grouped together in the south-east corner of the terrace, opposite the east wing of the agora. The larger eastern building, a long (23 × 16 m) rectangular building with a niche in its north side, was originally identified as a library. Inside the building, embedded in Late Roman walls, fragments of inscriptions and statues were discovered, among them the colossal heads of the acrolithic statues of Athena and the emperor Titus (Stefanidou-Tiveriou Reference Stefanidou-Tiveriou2001). Next to it, to the west, stood a small cultic edifice (8.50 × 9.20 m) with three large niches opening in each one of its three walls. The recent and new interpretation of the buildings of the north terrace as temples of the imperial cult (Stefanidou-Tiveriou Reference Stefanidou-Tiveriou2009, 620–3) indicates that this raised terrace could have been an area sacra bearing a series of religious buildings facing onto the open square in the south. It is unknown whether a great temple, like the Capitolium that M. Vickers (Reference Vickers1970, 251) imagined at the site of the Basilica of St Demetrius, stood in the centre of this terrace, but the resemblance to the plan of the forum of the Roman colony of Philippi (Sève and Weber Reference Sève and Weber1986) is so obvious that it has even been suggested that both complexes were the work of a single architect (Velenis Reference Velenis1990–5, 129–42). In Philippi, the public square, which was also surrounded by a three-sided portico, was orientated towards a monumental terrace bearing at least three frontal temples (possibly dedicated to the Capitoline triad). The clear division between the public square and area sacra that is often apparent in the plan of the fora of the Roman cities in Italy or the provinces (Todd Reference Todd, Grew and Hobley1985, 58), such as Philippi, is a feature that in many ways reflects the Roman spatial logic of a hierarchically structured space.

There is no doubt about the Greek character of Thessaloniki, which was so proudly attested by its participation in the Panhellenion of Hadrian (Spawforth and Walker Reference Spawforth and Walker1985, 79–81). At the same time, however, it is also certain that, due to its geographic position and its character as the base for Roman administration, Thessaloniki attained a rather more cosmopolitan character. This character is reflected not only in its large-scale architecture, such as the impressive building for spectacles (theatre–stadium) which was discovered in the eastern part of the intra muros city (Adam-Veleni Reference Adam-Veleni and Lane Fox2011, 558), but also in the axial layout of the broader area of the agora. As the monuments of Roman Thessaloniki have gradually come to light, thanks to the ongoing Metro excavations, it is becoming clear that the cosmopolitan centre of Macedonia reflects in many ways the mixed Graeco-Roman culture of the east (Yegül Reference Yegül and Fentress2000, 140–1). In this framework, the tradition of Hellenistic architecture survives everywhere (for instance in development on successive terraces), but also present are spatial and architectural elements, such as the cryptoporticus of the agora, of contemporary Roman architecture.

A development which also relates to changes in spatial organisation is the growing tendency to remove many of the commercial or manufacturing activities from the main area of the agora. These activities, which for hundreds of years were an inseparable part of the civic function of the site, gradually found shelter in new complexes (quite often in the form of colonnaded courts) built around the main complex of the agora. Nothing reflects this trend better than the so-called Roman Agora that the Athenians built at the end of the first century bc as a base for wholesale or even retail commerce (Hoff Reference Hoff, Walker and Cameron1989, 1–8). The Agora (it should be noted that the term is used indiscriminately for both commercial and civic agoras) gave monumental character to an area where quite probably an open market already existed (Fig. 2. no. 2). Although Hellenistic in origin (Coulton Reference Coulton1976, 174–5), the idea of extending the functionality of the agora through the construction of surrounding complexes which sheltered different aspects of urban life (food selling, manufacturing, recreation and leisure, etc.) was now becoming a standard urban feature of all the cities and towns of the empire. In Athens the application of this concept took a monumental form with the construction of another large-scale building, the Library of Hadrian (second century ad), which upgraded the region east of the Agora (Fig. 2 no. 3) as a second important civic nucleus of the city (Spetsieri-Choremi Reference Spetsieri-Choremi1995, 137–47). The addition of the luxurious new building to the east of the old Agora has been compared with the construction of the imperial fora around the Forum Romanum (Shear Reference Shear1981). However, in reality it seems more likely that it is the result of the constant pressure on Athens to provide services to citizens and visitors through new public spaces. S. Walker (Reference Walker, Hoff and Rotroff1997, 68) detected a similar pattern in other great cities of the east, like Ephesos and Kyrene, and in that group we should probably add Thessaloniki, since there is evidence that the area south of the agora was occupied by similar great complexes of commercial or recreational character (Mentzos Reference Mentzos1997, 383). It is undeniable that the urban centre of Athens during the Imperial period attained a monumental character that was unrivalled by the rest of the Greek cities (Vlizos Reference Vlizos2008). This is as much due to the importance of the city as a cultural capital as to the ability of the Athenians to attract great donors. However, the trend was by no means restricted only to the large urban centres. On the contrary, even smaller cities tried to follow this path of urban development in order to maximise the functionality and monumentality of the urban centre. In Thasos (Grandjean and Salviat Reference Grandjean and Salviat2000, fig. 21, nos. 6 and 38) small courts were added behind the stoas of the agora in order to shelter different public activities (religious or commercial). In Argos the area north of the agora became a second important urban nucleus (Fig. 5) with large-scale buildings like the monumental religious complex (Asklepieion, later Thermal Baths) and the odeion (Etienne et al. Reference Etienne, Aupert, Marc and Sève1994, 189; Aupert and Ginouvès Reference Aupert, Ginouvès, Walker and Cameron1989, 151–5), while in Thera the need to extend the mountainous agora led to the construction of a new north terrace which held monuments commemorating the great families of the city (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1899–1902 vol. 3, 124; Quéré Reference Quéré and Giannikouri2011, 332–3). The new trend is even more clearly reflected in the construction of a specialised building designed to shelter vegetable and meat markets or even retail commerce. This building, which is mentioned in a number of inscriptions (Mantinea, Sparta, unidentified Laconian city, Andros, Tegea) as μάκελλος, seems to be the Greek version of the Latin macellum (Cartledge and Spawforth Reference Cartledge and Spawforth1992, 130–1), a specific building type that was originally developed for food selling activities (Ruyt Reference Ruyt1983, 230–5). Commercial markets, along with baths, reflect the kind of social logic that regards the city as an institution designed to offer specialised services to citizens and the inhabitants of surrounding areas (Engels Reference Engels1990, 121–31). In contrast to the itinerant character of the open markets, the μάκελλος or macellum served the daily needs of the citizens in a controlled environment, where public hygiene and state control were secured (Ruyt Reference Ruyt1983, 177–86).

Fig. 5. The agora of Argos (source: Marchetti and Rizakis Reference Marchetti and Rizakis1995, 495 fig. 13 and Aupert and Ginouvès Reference Aupert, Ginouvès, Walker and Cameron1989, fig. 57).

Naturally the process described above does not necessarily imply that every manufacturing or retailing activity was completely removed from the agora. Despite the rapid monumentalisation, the agora still retained areas where, for instance, retailers, bankers, manufacturers or metal workers produced and sold products or provided services. For many years after the destruction of Sulla and at least until its renovation in the second century ad, the abandoned Hellenistic south square in the Athenian Agora (Fig. 2 no. 4) was a base for small workshops (Thompson Reference Thompson1960, 359–63), while the ‘Library of Pantainos’ (Fig. 2 no. 5) at the south-east entrance included a sculptor's workshop (Shear Reference Shear1973, 144–6). Similar manufacturing activities were also housed at Argos in Building K, a large renovated building on the north side of the agora (Fig. 5), which had small rooms with wells arranged around a central court (Moretti, Aupert and Pariente Reference Moretti, Aupert and Pariente1989, 710).

The transformation of the agora into an architecturally framed space was followed in many cases by the trend to give monumental character to the entrances or main accesses. The idea of an enclosed space requires the existence of points of entrance or exit, which quite often were marked by monumental gates. The addition of monumental entrances to a previously open space enhances the notion that the agora was becoming an autonomous enclosed space isolated from the rest of the city. In the Athenian Agora the exit to the east (Plateia Street), towards the great Agora of Augustus and Caesar (Fig. 2 no. 6), was marked by a single-bay arch, built late in the first century ad (Shear Reference Shear1975, 385–9). A similar single-bay arch (fourth century ad) marked the entrance to the north side of the agora of Argos (Croissant Reference Croissant1970, 788–93), indicating a clear decision to give monumental character to this previously open area of the agora. A triple-bay arch, which was a donation of the Spartan notable C. Iulius Eurycles Herculanus, was added to the south entrance of the agora of Mantinea (Fig. 3) at the beginning of the second century ad (Fougères Reference Fougères1890, 267–9), while a large propylon with three openings was built at the time of Hadrian in the coastal Thracian city of Maroneia (Kokkotaki Reference Kokkotaki2003, 13–16), at a point which has recently been identified as the entrance to the agora.

Τhe monumentality of the entrances is best manifested in the agora of Kos (late fourth – early third century bc), where after a devastating earthquake in the mid-second century ad (ad 142) the north stoa of the complex was remodelled (Rocco and Livadiotti Reference Rocco, Livadiotti and Giannikouri2011, 401–20) as an elaborate propylon which allowed the connection between the agora and the area of the harbour where an old fish market (Rocco and Livadioti Reference Rocco, Livadiotti and Giannikouri2011, 394) existed. The central part of the propylon had the form of a large (20.69 × 20 m) and lavishly built temple of the Corinthian order which was possibly dedicated to the imperial cult (Rocco and Livadiotti Reference Rocco, Livadiotti and Giannikouri2011, 416). Curiously, the temple did not open towards the interior of the agora but towards the harbour, functioning as the central temple in the north agora (fish market), which was also monumentalised by the addition of marble paving. The rear part of the temple, which looked towards the long court of the agora, took the form of a nymphaeum, with an elaborate facade articulated by three niches. On either side of the central hall there were four vaulted opus caementicium passageways, the facade of which had the form of an arch framed by half columns. The propylon stood on top of a raised terrace, paved by marble slabs and accessible by a staircase more than 50 m wide, which enhanced the monumentality of the facade. The project, which is reminiscent of other great facades at religious and urban sites in the Roman east, such as the sanctuary of Bel at Palmyra or the entrance to the agora of Apamea (Rocco and Livadiotti Reference Rocco, Livadiotti and Giannikouri2011, 417), was designed in order to have a strong visual impact on visitors coming from the harbour.

Closely related to the monumentality of entrances was the trend to frame the main arteries leading to the agora with stoas, a form of colonnaded street that from the Early Imperial period appears in every major urban centre in the east (Ball Reference Ball1994). In Athens this type was introduced at the end of the first century bc, when two long stoas (Fig. 2 no. 7) framed the Panathenaic street near the Agora (Nikolopoulou Reference Nikolopoulou1971). Although the materials used came from older buildings (mainly buildings destroyed by Sulla), it is obvious that from very early on Athens started to develop a monumental framework in imitation of the large metropoleis of Asia Minor. Τhe colonnaded street combined the functionality of long stoas with the formal – quite often ceremonial – character of the great arteries that crossed the cities (like the Panathenaic street). Moreover, they emphasised the central position of the agora as the nucleus of the city, connecting it with other complexes such as the city gates. Once more the most typical example of this urban feature comes from Athens (Fig. 2 no. 6) where a small colonnaded street (length 75 m) was built in the late first century ad in order to connect the main Agora to the Agora of Caesar and Augustus to the east (Shear Reference Shear1975, 385–9). The same trend towards monumentalising the main thoroughfares can also be noticed in cities that never attained the metropolitan character of Athens. In rural Mantinea, for instance, a large stoa, which was probably a donation from C. Iulius Herculanus (Fig. 3), framed the south access to the agora. In this case, and bearing in mind the role of Herculanus as a patron of the Roman colony of Corinth (Spawforth Reference Spawforth1978, 251–2), where a large colonnaded street (the Lechaion road) led to the forum (Fig. 6), it is not impossible to assume that Corinth was the source of inspiration. A similar attempt to achieve the effect of the colonnaded street has been seen by C. Witschel (Reference Witschel and Hoepfner1997, 39) in the columnar buildings that stood on either side of the south entrance in the agora of Thera, while in Thasos the main thoroughfare (although not a colonnaded street in the strict sense) had a ceremonial character, enhanced by the great arch that marked the entrance to the civic centre (Marc Reference Marc1993, 585–92). Although in Elis the agora was not transformed into an enclosed space, the road that led to the agora from the south took the form of a colonnaded street during the Early Imperial period (Andreou Reference Andreou and Αndreou2004, 22). The recent finds from the Metro excavation in Thessaloniki (Makropoulou and Tzavrani Reference Makropoulou and Tzavrani2013) indicate that the part of the main decumanus of the city which passed near the complex of the agora also had the form of an enormous colonnaded road, which approached the monumentality of the great urban centres of the east.

Fig. 6. The forum of Corinth in the first century ad.

The developments (introduction of the enclosed agora, monumentality of entrances and accesses, removal of food selling and manufacturing activities) that we examined briefly above are by no means novelties of the Roman period. Instead many urban centres in the east as well as in Greece (Pella, Demetrias, Kos) applied the same urban model on a monumental scale during the Hellenistic period. For many cities of Greece, however, it was the integration into the empire and the stability that the new situation brought that for the first time allowed the modernisation of the urban plan and the monumentalisation of the urban landscape.

3. ARCHITECTURE

In the field of architecture, the adaptation of the urban landscape to the new needs of the Imperial period was a process that differed greatly from city to city and from region to region. In many small cities and towns, due to limited financial resources or the inability to attract great donors, building activity was limited, with the greatest effort being directed to repairs, alterations, modifications or even additions to older buildings in order to meet the new civic needs. Among the many repair works attested for the period between the first century bc and the second century ad,Footnote 3 the most characteristic example is probably the case of the city of Thera, where an old building of the agora (third century bc) in the rare form of a closed stoa was first repaired and then renovated in order to reach the standards of a multifunctional civic building. The project, which was funded by the notable local benefactor, T. Flavius Cleitosthenes (Nigdelis Reference Nigdelis1990, 100–1) included the replacement of the roof, the transformation of the northern part of the building into an imperial cult temple, decoration with statues and imagines clipeatae and the addition of a small Roman-type bath outside the south end. The new lavish character of the building is best manifested in its new title, that of the Βασιλική Στοά (Witschel Reference Witschel and Hoepfner1997, 25–9), which appears for the first time during this period.

For many small cities or towns like Thera, which could not afford expensive building projects, the repairs, alterations and conversions of pre-existing buildings, such as the one attested in Sikyon where the house of the old Hellenistic tyrant Kleon (Kantiréa Reference Kantiréa, Rizakis and Camia2008) was converted to a temple of the imperial cult (Pausanias 2.8.1), were more than important for the development and renovation of public space.

Naturally the construction of new buildings, either as a result of a donation from a member of the local elite or, even better, as a result of an imperial donation, was a matter of civic pride (especially when the new building was donated by a member of the imperial house) and an embellishment to the monumental character of the urban landscape. Most of the new buildings of the period were constructed in order to meet the demands of ‘Roman’ life, like the ability to provide specialised services, many of which related to water abundance. Buildings of public amenities (baths, latrines, fountains), religious buildings (many of which were built in order to house the imperial cult), civic buildings (stoas, civic offices and even basilicas) and buildings for culture and spectacles (odeia, theatres) were some of the new additions to the urban landscape of the agora.

A significant number of the new buildings seem to belong to the long-established tradition of Greek architecture (Classical and Hellenistic). Hence, the architectural landscape of the agora retained, to a large extent, an appearance that was, or seemed to be, archetypically Greek. Nostalgia, or even the deliberate promotion or reconstruction (as in the case of the ‘itinerant temples’ in Athens) of the Classical past, was after all one of the most interesting reactions of local societies to incorporation into an antique-loving empire (Alcock Reference Alcock and Fentress2000, 222). Extensive repair works οn ancient buildings (like the Augustan restoration of the monuments of the Acropolis) may also have inspired a trend towards classicism that is reflected especially in architectural details (Shear Reference Shear1997, 495–507).

Despite the preservation (and frequent enhancement) of this Classical setting, which greatly attracted Roman visitors, the architectural framework of the agora was also open to influences from contemporary Roman architecture, following a trend towards monumentality that characterised the urban landscape in many Roman cities. The expansion of Roman power, originally in the Italian peninsula and later in Gaul and Spain, challenged Roman architects to create a series of new building types which very soon became the basic (and quite often standardised) repertoire for provincial urban architecture. The standardisation of certain building types played a significant role in the creation of an architectural landscape which contained elements easily recognisable by visitors and characteristic of an urban lifestyle that gradually prevailed throughout the empire. Thus, it is clear that the adoption of Roman building types was a process relevant to the gradual prevalence of an architectural framework that in many cases proved to be the most characteristic expression of the Roman character (‘romanitas’) of a city. As this new urban model developed across the empire, the Greeks accepted elements that, in a sense, modernised the traditional architectural landscapes of their cities.

This new urban framework is best reflected by the Roman bath (Fagan Reference Fagan2001, 403–26), a building that became a basic addition to the infrastructure of all the important public spaces of the ancient city. Although there is no doubt that the original concept of a public bath was Greek (Ginouvès Reference Ginouvès1962; Gill Reference Gill2004), the Roman-style bath, due to its advanced hydraulic and heating engineering, upgraded the experience of public bathing and therefore became one of the Roman building types that were successfully introduced into the traditional framework of the Greek city. Public bathing in a luxurious environment was one of the fundamental amenities of Roman life, and therefore the construction of a bath near major public spaces was a necessary step towards modernisation for all Greek cities. Even in remote Thera, which was devastated by earthquakes and dependent on local benefactors for simple restoration works, a small bath (an addition to the above-mentioned Βασιλική Στοά) was deemed necessary in the renovation programme of the second century ad (Hiller von Gaertringen Reference Hiller von Gaertringen1899–1902 vol. 1, 237). A larger, more typical example appears in Sikyon, where a well-preserved bath dominates the north side of the civic centre, while in Argos two large-scale bath complexes (both of which replaced older buildings) exploited the abundance of water that the Roman aqueduct brought into the city (Etienne et al. Reference Etienne, Aupert, Marc and Sève1994, 194). In almost every case the plan of the building follows the conventional Roman plan with its succession of rooms of different temperatures and auxiliary spaces. Even when an old building was used, as in Athens (Artz Reference Artz2010) where an old Hellenistic bath (βαλανεῖον) located outside the south-west corner of the Agora was converted to a Roman-style bath in the late first century bc, the interior was converted in such a way as to follow the typical plan of Roman baths. The same Roman influence can also be traced in the construction of monumental fountains, like the elaborate fountain that the family of Tiberii Iulii donated in Argos (Touchais et al. Reference Touchais, Marchetti, Feissel, Thalmann, Piérart and Aupert1978, 784) or latrines (like the one at the eastern entrance of the Athenian Agora), buildings that exploited Roman know-how in hydraulic engineering (Neudecker Reference Neudecker1994). The stability of the empire secured the existence and maintenance of long aqueducts, and the abundance of water that these brought to many waterless cities like Argos added a new note to the monumentality of the urban centre, while at the same time securing public hygiene (Scobie Reference Scobie1986, 399–433).

In examining the introduction of Roman building techniques in the traditional architectural framework of the agora special attention should be given to the Roman basilica (Fig. 2 no. 8) which, during the early years of the reign of Hadrian, was built on the north side of the Agora of Athens (Shear Reference Shear1973, 134–8). The building, part of which is still visible next to the rail tracks, was built at right angles to the main square, next to an older (end of first century bc) luxurious columnar civic building, possibly of imperial donation (Shear Reference Shear1971, 261–5; Schmalz Reference Schmalz1994, 75–9). The two buildings together comprised a large civic complex, the importance of which has not yet been fully evaluated (Burden Reference Burden1999, 139–40). The plan is reminiscent of the great elongated basilicas in Verona, Pompeii and Tarraco or, even more so, the great basilica in Corinth (dominating the north entrance of the forum) that was built at approximately the same time (Fowler and Stillwell Reference Fowler and Stillwell1932, 193–211). The basilica of the Athenian Agora is a very interesting aspect of the great Hadrianic building project that changed the form of Athens during the second century ad. The basilica was the archetypical building of Roman architecture, sheltering different administrative, social, juridical or even financial activities (Gros Reference Gros1996, 235–60). The construction of such a typically Roman building in the centre of Athens, especially during a time of cultural renaissance, raises some interesting questions. Which part of the Athenian population did the building address? Was it built in order to cover the needs of a specific group with Roman profile, or were the civic needs of Roman Athens such that the construction of a Roman basilica was deemed necessary? A new thorough study of the building might reveal much about the social meaning of the basilica in the Hadrianic context of the Athenian Agora. Until then we can only speculate. P. Zanker (Reference Zanker and Fentress2000, 35) has argued that the basilica reflects nothing other than the Roman character (romanitas) of a city. Based on his observation, it is quite possible to assume that Hadrianic Athens (despite its Classical allure) was obviously a city with social and public needs that demanded the construction of such a building. Imperial interest and the foundation of the Panhellenion had upgraded Athens to the level of a Roman metropolis (Boatwright Reference Boatwright2003, 144–57), and in such a city the need for a building related to the basic functions of Roman public life is obvious.

Far from Athens, in north Greece, in the Roman province of Macedonia, a large basilica of the second–third century ad has been discovered at the archaeological site of Terpni in the plain of Serres (Karamperi Reference Karamperi1994, 607). The building was a donation from a local Iulia (Samsaris Reference Samsaris1980, 1–7) and dominated (along with a complex of public baths) the centre of a small fortified city (πόλις), which has not yet been securely identified. It is clear that this small city in the agrarian heartland of Macedonia lacked the metropolitan character of Athens which would have justified the existence of a large Roman public building. It is, however, also clear that the degree of Romanisation in Macedonia and Thrace differed greatly from that of the cities of Achaea, and Roman-type buildings were more common. Recently the excavations in Argos Orestikon, a tribal centre in Upper Macedonia, have revealed another great public building of the Roman period, which might have functioned as a curia or assembly hall (Damaskos Reference Damaskos2006, 911–22).

As in other parts of the empire, the introduction of new building techniques and materials (in particular, opus caementicium ) into the traditional architectural framework of the Greek-speaking world before the end of the first century ad was limited. Undoubtedly the expertise of local craftsmen in ashlar masonry, as well as the lack of the necessary raw material (the volcanic sand) that produced the Italian mortar, were decisive factors in the delay (or even hesitance) in adopting Roman building techniques. After all, the realisation of the potential that the new material offered was not an instant epiphany, but came gradually through a long process of development and experimentation during the first century ad. The turning-point for the widespread use of the new material was probably the end of the first century ad, when Roman architects finally mastered the new techniques and the quality improved. At the same time, the new building methods started – hesitantly at the beginning – to find their way into the architecture of the Greek cities. As shown by M. Waelkens (Reference Waelkens, MacReady and Thompson1987, 102), the adoption of Roman building techniques, especially in the east, was a complicated process that involved a lot of experimentation, which often resulted in mixed types – hybrids that combined elements from both Hellenistic and Roman traditions (for instance the technique known as opus mixtum). At the end of the first century and the beginning of the second century ad, brick- and mortar-built buildings appeared in the agora of every major city and town in southern Greece: baths (the agoras of Sikyon and Corcyra), elaborate fountains (Argos, the Nymphaeum at Athens), latrines (Athens), μάκελλοι (Mantinea), stoas (the Roman stoa in Sparta) or odeia like the one in Gortyna (Di Vita and Englezou Reference Di Vita and Englezou2006, 671–701). Unique among them stands the great religious complex that was built at the end of the first century ad on the north side of the agora of Argos (Fig. 5). The plan consisted of an elongated central colonnaded court, which on its north side had an axially placed central temple dedicated to Asklepios and quite possibly the imperial cult. On the roof of the cella of this central temple a pitched brick vaulting technique, an old Egyptian practice executed with Roman material, was used for the first time in Roman architecture (Aupert and Ginouvès Reference Aupert, Ginouvès, Walker and Cameron1989, 155). The building is of extreme importance for the study of the architecture of Roman Greece, not only because it was a major construction project (possibly a Domitian imperial donation) but also because it is proof that Roman Greece was (occasionally) in the avant garde of architectural developments (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2010, 447–67).

Different reasons, including the superiority of Roman building techniques, the need for specific upgraded building types (like Roman baths), modernisation or even the will of a donor to promote a more Roman profile, led to the gradual adoption of elements of Roman architecture. However, the extent to which the systematic use of new materials can be regarded as a sufficient indication of Romanisation is debatable. Cases like the enormous cryptoporticus that supported the south side of the agora of Thessaloniki (Boli and Skiadaresis Reference Boli, Skiadaresis and Adam-Veleni2003, 150) show that the use of opus caementicium allowed the architects to apply a framework of monumental architecture that could overcome all difficulties of terrain and create a monumental urban landscape. The use of the new materials for the first time also allowed the appearance of great roofed buildings like odeia or thermae, where the emphasis was placed on internal space. These new buildings possibly marked a change in the traditional hypaethral character of the agora. An intriguing issue is, of course, the influence that these new materials might have had on an aesthetic level. The great Roman stoa of Sparta, in the facade of which archaising capitals were used (Waywell and Wilkes Reference Waywell and Wilkes1994, 410), possibly offers an indication that the degree to which the new materials changed the architectural landscape must have been limited. After all, bricks and caementicium were materials that were not visible and quite often covered by the use of marble or ashlars or even by archaising and classicising architectural elements.

5. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE FORUM IN THE ROMAN COLONIES

The formation and development of public space followed a different path in the Roman colonies which were founded during the Late Republican period (second half of the first century bc) in Achaea and Macedonia. These new cities were part of a Caesarean and later Augustan plan to create peripheral centres that would have controlled people, territories and routes (Rizakis Reference Rizakis and Alcock1997, 17). In contrast to Roman foundations in the west, many of these colonies (Corinth, Patras, Philippi, Dion and Knossos in Crete) replaced pre-existing cities with long histories and already developed urban environments.

Numerous reasons, such as abandonment after the war (Corinth), decline in population (Philippi), strategic location (Patras) or roles as military and religious centres that opposed Roman authority (Dion, Pella, Knossos, Corinth), played equal roles in the decision to settle Latin-speaking colonists in these areas. The change in political status was followed in every case by changes in the traditional landowning scheme (Rizakis Reference Rizakis1996, 225–34), since the confiscated land became public property which was distributed to the first body of colonists. As more evidence emerges for these Roman cities in Greece (Sweetman Reference Sweetman2011), it is becoming clear that the foundation of the colony was not just a constitutional change but made a drastic intervention in social, financial and cultural life on many different levels. How, however, is this Roman presence reflected in the development of the urban environment and, more specifically, in the organisation and architecture of the forum?

Archaeological evidence from a number of sitesFootnote 4 where systematic excavations have provided a more or less complete view of the area of the forum (Corinth, Dion, Philippi and to a lesser extent Patras and Knossos) indicates that the first colonists as well as their descendants, who became the elite in the local hierarchy, gradually changed the old urban landscape on the basis of a characteristically Roman architectural and spatial model. In the Caesarean colony of Corinth, the development of a large space (c.13000 m2) in the centre of the city (upper Lechaion road valley), which was levelled and landscaped in order to become the forum of the colony (Romano Reference Romano, Williams and Bookidis2003), started soon after the first settlement, while the first large Roman-type buildings, such as the podium temple E on the west side of the forum (Walbank Reference Walbank1989) or the Julian Basilica (Weinberg Reference Weinberg1960) on the east, appeared in the Augustan period. In the Roman colony of Philippi in Macedonia the first forum (Sève Reference Sève1996) was not developed until the mid-first century ad (the time of Claudius), while in Dion the transformation of the city centre occurred late in the second century ad (Pantermalis Reference Pantermalis2002). Unfortunately, there is a significant gap in our knowledge concerning the early development of the Roman colonies in Greece, especially the process of creating a new urban environment. Of special importance would have been to ascertain the relationship between new (forum) and old (agora) public spaces, an issue which still remains open due to different approaches and interpretations, since, in many cases, as in Phillipi, the old agora itself has not been securely identified. Nevertheless, by starting to follow the process of developing the forum of a colony it becomes clear that a number of questions can be raised – questions that basically reflect the complexity of the creation of a new cultural environment. Did the settlers transform the urban environment of the old agora to meet the new demands of Roman public life? How and in what context were the old buildings used? Were old agora and Roman forum two different public units of the Roman city and, if so, what kind of public needs did they cover? Corinth can provide answers to some of these questions, especially the reuse of old buildings and their incorporation into the new urban framework. Even though the colonists levelled and covered many of the small shrines and monuments that existed in the space where the forum later developed (Fig. 6), they preserved two important buildings of the pre-Roman city: the South Stoa (fourth century bc) and the Archaic Temple (sixth century bc). The South Stoa, which actually determined the length of the forum (Williams Reference Williams and Gregory1993, 33), seems to have served many of the public needs of the early colony (Broneer Reference Broneer1951, 100–60).

In Philippi the investigation in the deeper strata of the central court of the forum has shown that this was built in an area which was not the agora of the pre-Roman city (Sève Reference Sève1985, 870), while under the forum of Dion foundations of buildings that might have belonged to the agora of the pre-Roman city have been traced. From one such early Hellenistic building (Christodoulou Reference Christodoulou2000, 105), which has been identified as a bouleuterion, come a number of architectural members and a large frieze depicting shields and cuirasses that were incorporated into the basilica of the second century ad (Christodoulou Reference Christodoulou2007).

Hopefully, new evidence (especially geomagnetic and spatial technologies) in the near future can provide sounder answers concerning the topography and development of these cities (Provost and Boyd Reference Provost and Boyd2003). However, given the importance of the forum in Roman public life, it is very possible that the construction of a Roman-type forum belonged to the original plan of these cities, even if the actual construction was not completed until much later. After all, Roman planning and architecture were largely based on the repetition of successful types, which not only could be applied on every terrain but were also ideologically laden as symbols of Roman identity.

As in many other Roman cities and towns, the development of the forum in the Roman colonies in Greece seems to follow a specific path, the most characteristic features of which can be summarised in the following points.

-

• The application – depending on local conditions – of an axial grid plan that was based on cohesion and symmetry. Public buildings and the main public square (forum) were normally located in the centre of the grid, where the two main roads (decumanus maximus and cardo maximus) met. Evidence of this spatial design has been traced in Corinth (Romano Reference Romano, Williams and Bookidis2003), where the Roman planners adapted the new city grid to the pre-existing urban environment (Fig. 6). The place chosen by the agrimensores for the site of the forum was at the centre of the city, with monumental buildings ready for use and an abundance of water. The site was apparently the topographical centre of the colony, the single point (locus gromae) from where the city plan was drawn (Romano Reference Romano and Gregory1993, 15). The development of the grid started immediately after the first settlement and the colonists managed, after a great deal of levelling and depositions, to create a large rectangular space that was not fully developed until the second century ad. In Philippi, where the elongated city plan was determined by the course of the old Hellenistic wall and the steep acropolis that dominated the site, the forum was built in the centre of the grid next to the Via Egnatia, which crossed through the city acting as the main decumanus (Poulter and Strange Reference Poulter and Strange1998, 453–63). In Dion (Fig. 7) an extensive project of the late second century ad renewed the city centre, which occupied a large terrace over the main cardo with the forum located on the north side of this insula (Pantermalis Reference Pantermalis2002, 417–24). Unfortunately, the evidence is more fragmentary for the rest of the colonies (Patras, Knossos, Kassandreia). The Roman colony of Pella, which was founded as it seems on virgin soil (2 km to the west of the old Pella), could provide valuable information about Roman planning in the east, but hitherto only a round building has been securely identified in the area of the forum (Chrysostomou Reference Chrysostomou, Lilimbaki-Akamati and Akamatis2003, 95).

-

• Emphasis was placed on a building or group of buildings (normally temples dedicated to the official deities of the city or the Capitoline triad) with a prominent position in the spatial scheme (Barton Reference Barton and Temporini1982, 259–340; Hesberg Reference Hesberg1985, 127; Todd Reference Todd, Grew and Hobley1985, 61; Quinn and Wilson Reference Quinn and Wilson2013). This was achieved either through the central position of the building in the middle of one of the sides of the square, like the ‘Sebasteion’ (Fig. 7) in the forum of Dion (Pantermalis Reference Pantermalis2002, 417–24), or through its placement on a high terrace overlooking the square, as in the forum of Philippi (Sève and Weber Reference Sève and Weber1986, 579–81). The division of space into area sacra and a public square, which is so characteristically attested in Corinth and Philippi, is one of the basic morphological features of the Roman forum and one of the greatest differences from the Greek agora. The forum–area sacra complex, which dominated the urban centre in hundreds of Roman cities and towns in Italy, Gaul, Spain, Germany, Britain and Africa, was not an imitation of the Forum Romanum but an attempt to create a new kind of strictly organised public space, which would have embodied the principles of Roman society (Zanker Reference Zanker and Fentress2000, 33–4). The Greek agora, despite the monumentalisation and other changes, remained mostly an open space designed for gathering and exchange. Instead, the Roman forum was a closed space, hierarchically organised, where each architectural unit had a specific functional and symbolic role (Zanker Reference Zanker1990, 328). This spatial logic is clearly present in the organisation of the surviving fora in the Roman colonies of Greece.

-

• The construction of Roman-type buildings, some of which, like the basilica or curia, were inherently related to the practice of Roman public life. As already mentioned, these building types never found a wide distribution in the east and were only occasionally and selectively adopted by the Greeks (baths, arch and basilica). By contrast, Roman-style public buildings or monuments, like the rostra (Corinth, Philippi), the curia (Philippi, Dion), the basilica (Corinth, Philippi, Dion, Knossos), the arch (Corinth, Philippi), the macellum (Corinth, Philippi, Dion) and the Roman podium temples, like the first temple E in Corinth (Walbank Reference Walbank1989, 361–94) or the three temples in Philippi (Sève and Weber Reference Sève and Weber1986, 579–81), are present in the colonies, creating an urban landscape that differed greatly from that of the Greek cities. Since in most of the cases – except Corinth – the evidence is fragmentary, we cannot be certain how soon after the foundation of the colony the settlers started to build Roman-style buildings. Corinth indicates that this might have happened relatively early, in the period of Augustus, but the conditions seem to differ from site to site.

Fig. 7. The forum of Dion in the late second century ad (source: Christodoulou Reference Christodoulou2007, 178 fig. 1).

The degree to which the architecture of the Roman cities influenced architectural developments in the Greek cities is still open to investigation. Although it is possible that the introduction of Roman architectural elements in the traditional architectural framework of the Greek cities could have been influenced by more than one source (for instance by itinerant Roman architects or even by Greek architects working in Italy), it is difficult to ignore the role that some of the colonies (especially the ones with the size and stature of Corinth) played as a source of inspiration.

For many years any attempt to approach the Roman colonies in Greece was based on the idea of their gradual Hellenisation. It is beyond any doubt that, in many of these eastern Roman foundations, a mixed Graeco-Roman civilisation gradually prevailed, which included elements (linguistic, artistic, architectural) from both traditions. However, we should not underestimate the fact that, at least until the Constitutio Antoniniana, the title of Roman citizen held by birthright by the Latin-speaking citizens of these cities drew a clear distinction between them and the Greeks. This difference was expressed in every instance of public or private relationships (for instance, in patronage or in juridical matters), as well as in material culture. The obvious Roman orientation that is so vividly attested in the archaeological record was related to the ideological framework of the Roman colony as well as to the aesthetic, functional and ideological preferences of the persons who held the power and title of Roman citizen. This ‘romanitas’ finds its best manifestation in the forum, which, as the basic civic, religious and (most importantly) symbolic centre of the Roman settlement, was developed in such a way so as to express (through its architecture and plan) the Roman character of the city. After all, as remarked by P. Zanker (Reference Zanker and Fentress2000, 35), the forum was nothing less than the architectural reflection of the principles that ruled Roman society (strict hierarchy, pietas, social stratification).

5. EPILOGUE: GREEK AGORAS AND ROMAN FORA

Despite the loss of political autonomy and the abandonment or decline of many settlements with long histories, the cities of Greece enjoyed a relatively long period of peace and prosperity. Behind the standard image of degradation and fall that was so eloquently described by ancient Roman historians, a new political, financial and cultural reality had emerged, which Greeks gradually adopted as part of a new identity. The historical and cultural accomplishments of the past became one of the pillars upon which was built the vision of the Roman world, and this tradition ensured that many Greek cities avoided oblivion. The cities retained their autonomy, but at the same time became part of a new world extending much further than the boundaries of the Greek peninsula. Free movement of people and ideas in the security of the Roman domain allowed cultural interaction and mixture but also the existence of an almost globalised urban material culture.

In this period of change and transition the agora preserved its importance as a multifunctional public centre, which was visited daily by citizens and travellers for public or private work. It was not until Late Antiquity, when public practice changed radically, that the nucleus of civic life moved from public spaces to parishes and churches. As previously, the agora of the Roman period continued to attract a varied audience of people who sought to fulfil a variety of purposes, ranging from religious practice to commerce (Alcock Reference Alcock2002, 65). In spite of the loss of political autonomy the agora continued to function as the political and administrative centre of the city. It was there that the officers who dealt with local issues, established relationships with the central authority and secured the welfare of the citizens were based. As observed by S. Walker (Reference Walker, Hoff and Rotroff1997, 72) and others (Evangelidis Reference Evangelidis2008; Camia Reference Camia2011), special emphasis was given to the religious character of the place through the construction of new temples and altars, a trend which might reflect the introduction of the imperial cult into the traditional religious framework of the Greek city as well as the Augustan and imperial ideology of religious pietas.

The spatial organisation and architecture of the agora and its surroundings were not left unaffected during the long period of Roman imperium. On the contrary, a series of changes outline a development towards a new kind of public space, which was defined by monumentality and functionality. The most characteristic manifestation of this framework can be found in the description of a city that lacked all those features that comprised urban monumentality. When Pausanias (10.4.1) visited the small Phocian city of Panopeas he was astounded that a settlement with no basic public buildings, public spaces or infrastructure still held the status of a city (πόλις). In spite of the lack of monumental architecture and agora, Panopeas was, and still remained, a city, similar to Athens or Sparta. However, for Pausanias, a Greek who was raised in the monumental environment of the cites of Asia Minor, it is clear that the title πόλις referred not so much to the concept of an independent political entity as to a specific urban environment which was easily recognisable and therefore familiar to visitors.

Naturally the question which is raised is whether (and to what degree) these developments can be attributed to the incorporation of the Greek cities into the Roman empire. M. Waelkens (Reference Waelkens, MacReady and Thompson1987, 81), examining the spatial and architectural developments of the cities of Asia Minor, has observed that many building projects, like the great colonnaded plazas or the colonnaded streets, did not necessarily owe much to Roman influence. It is also obvious that Roman building types never achieved a widespread distribution and acceptance in the east and, whenever such Roman buildings were constructed, they were integrated into a basically Hellenistic architectural environment. If so, on what must any discussion concerning Romanisation of the urban environment be based? It is obvious that, if we regard the term as synonymous with a continuous flow of building types and other architectural elements from the west, the answer must be negative. The Greek-speaking east, and Greece in particular, were areas with a long architectural tradition and skilled architects or builders, who worked superbly with ashlar masonry. Instead, the term can be used in order to describe a process of urban development that transformed public spaces so as to adapt to the new demands of urban life. Architectural development was based predominantly on the existing repertoire of Classical and Hellenistic architecture, but gradually – after the end of the first century ad – it included elements derived from the contemporary architecture of the Roman world. More than anything else, the substance of Romanisation lies in the attempt of the cities to adapt their public spaces to a new urban model that required modern infrastructure, monumentality and realistic use of space. In some cases, as in Athens, factors relating to collective memory or the deliberate promotion of the glorious past might have played an equally important role in this process (Alcock Reference Alcock2002). Undoubtedly the agora of the Imperial period is a product of its era, an era based not only on the Classical civilisation of Greece but also on a widespread material culture that prevailed in every corner of the empire.

Roman colonies were the newest addition to the settlement pattern of Greece. Although they were established mostly over pre-existing Greek cities, they were surrounded by Greek cities and their population eventually consisted mostly of Greek-speakers, their material culture remained distinctively Roman. This identity is most characteristically reflected in the plan and architecture of their forum, which, as in many other Roman cities and towns in the west, was a space with great symbolic meaning as an ideological and physical extension of Rome. What remains to be considered is the degree to which these colonies functioned as vehicles of Romanisation for the rest of the Greek cities.