The introductory map in the Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens contains locations of numerous Classic period (a.d. 300–950) sites in the central Maya region that mark hieroglyphic accounts (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:10). While there is much evidence of political interaction between the southeastern sites of Copán and Quiriguá, in contrast, there is an absence of epigraphic knowledge within the zone between the southern lowland site of Cancuén and the highland site of Kaminaljuyú (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Prufer, Macri, Winterhalder and Kennett2014:339, Figure 1). This unfortunate lack of information pertaining to elite political or historical occurrences is most likely the result of the combination of not encountering ancient large-scale stela—altar cult practices in the region during ancient times—and/or recent civil war activities that have hindered late twentieth-century archaeological exploration within the Alta Verapaz region. Small events, therefore, can take on major significance.

A glimpse into the epigraphically recorded history of the Alta Verapaz occurred in May 2018, when a bulldozer extending a road-cut on private land located east of Cobán demolished a well-hidden earthen mound (Figures 1 and 2). This chance event, appearing in the press as an “inadvertent uncovering” of a ceramic figurine workshop (Brown Reference Brown2019; Chun Reference Chun2019; Wade Reference Wade2019), nonetheless provided a unique opportunity to investigate the interaction of “external communities” with an epicenter that is no longer present because of the current growth of the regional capital city of Cobán. These discoveries allow new perspectives from both context and the non-archaeologically documented objects within a small valley zone. Following the landowner's notification to official Ministry of Culture officials within Cobán, Woodfill and colleagues were able to obtain emergency National Science Foundation funding to excavate briefly on the eastern side of the property (Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019b). The team's efforts focused roughly 20 m to the east of the destroyed mound; the excavations revealed a separate residential section that provided contextualized comparative material of ceramic, lithic, and ceramic figural assemblages. The combined discoveries at this small valley site, named “El Aragón,” will allow for new perspectives in comparison to historic non-excavated ceramic collections residing in international museum collections. Analysis of the figural material is continuing by the senior author. Our objective in this article is to highlight a specific set of objects whose significance was recognized during laboratory processing of the non-excavated collection during August 2019.

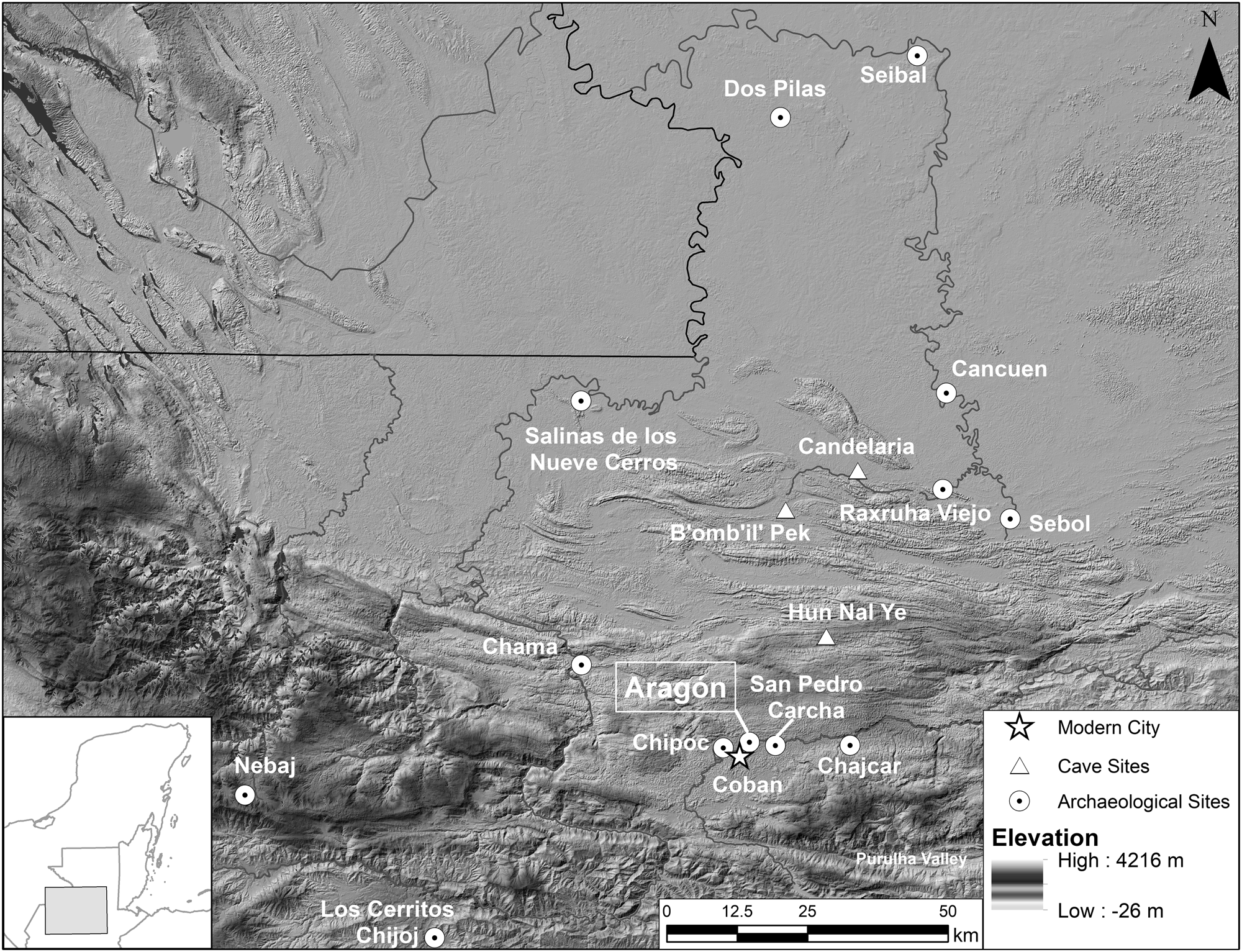

Figure 1. Map of the Transversal region, location of El Aragón, and the edge of the southern lowland zone, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Map created by Rivas.

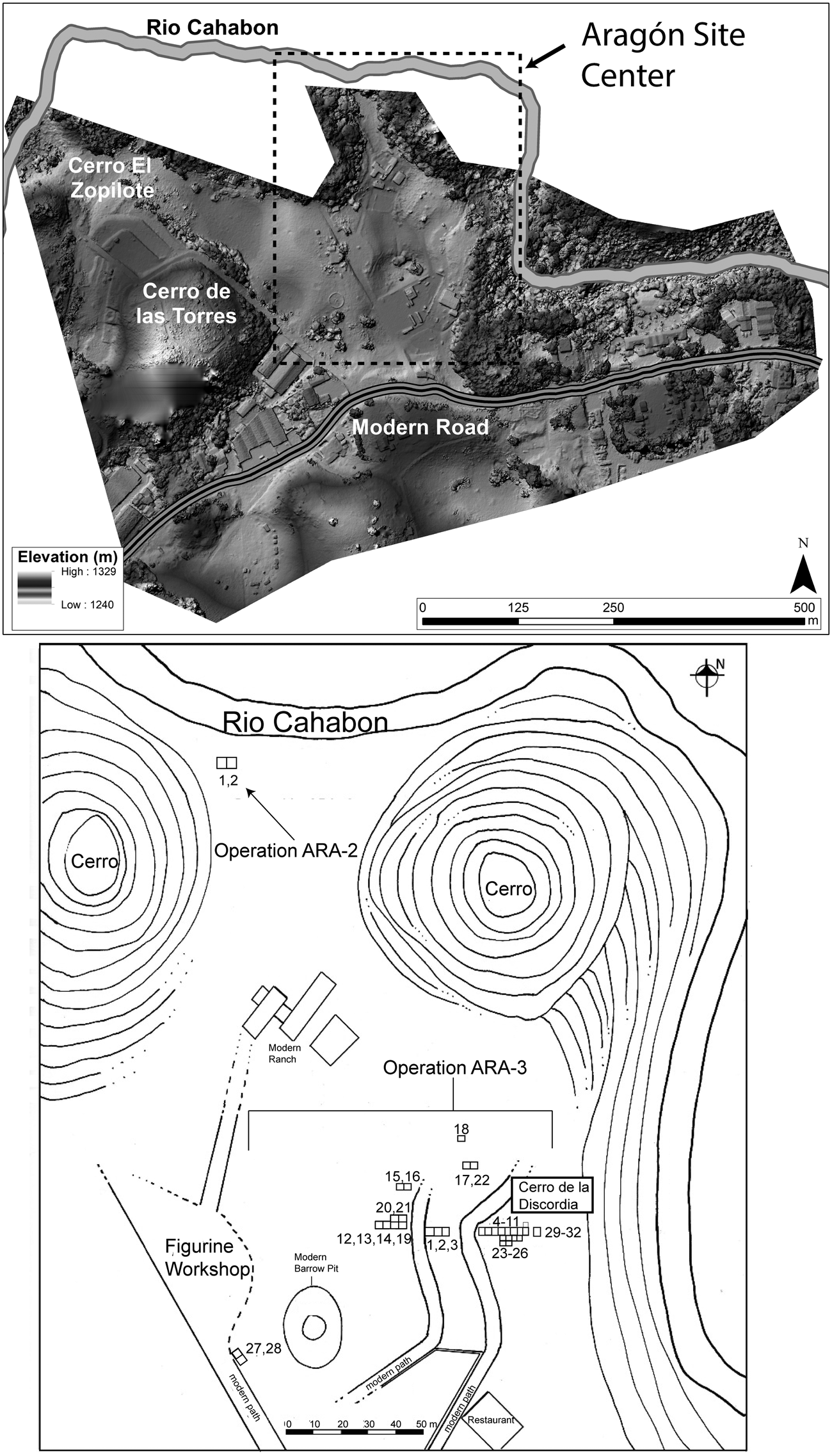

Figure 2. The currently known layout of the site of El Aragón: (top) orthophoto and (bottom) digital elevation model with the archaeological units arranged within the inset illustration. Maps created by Rivas, courtesy of the Nueve Cerros project.

THE DISCOVERY AND INVESTIGATION OF EL ARAGÓN

Like most archaeological “discoveries,” the archaeologists came on board well after the fact. In February 2018, contractor Pedro Archila was working to level a hill and build a road on one of his family's landholdings, in order to convert it into a housing development at the edge of the sprawling city of Cobán. After noticing artifacts coming out of a fresh cut, Archila stopped work and contacted his cousin, Julio Archila, the archaeological inspector for the region. Julio, in turn, contacted Woodfill, who visited the site in May and led a survey and salvage excavations two months later.

The fieldwork consisted of several interlocking parts. Woodfill flew a DJI Inspire 2 over the region to create a digital elevation model (DEM) and other products of aerial photogrammetry. Alexander Rivas mapped archaeological, geographic, and hydrologic features with a handheld Trimble GeoXH unit. Woodfill led excavations by local workmen and an archaeological team composed of members of the Cancuén and Nueve Cerros projects. All of the excavated material was then sent to the Nueve Cerros laboratory in Guatemala City and analyzed by project specialists.

Unfortunately, by the time the project began, the remnants of the workshop had been buried in approximately 3–4 meters of artificial fill. As a result, the excavations focused on four main contexts: concentrations of artifacts visible on the surface in locations slated for development, hilltops, buried cultural strata made visible by road-cuts, and a looted housemound near the Cahabón River. Project members conducted a sweeping surface collection project in sectors that were damaged by new and older construction.

In addition to the recent damage to the site, the land had already been extensively modified, as is visible in Figure 2. There is an automotive workshop, a restaurant, four graded roads for use by family members and employees, a horse stable, two residences, a cellphone tower, and a large collection of shipping containers that are currently in use, and excavations revealed the extent of earlier modifications. In the latter part of the twentieth century, the land was leased by a paving company that built temporary structures atop two of the smaller hilltops, and a densely packed gravel road that connected them to the primary road, which forms the southern edge of the family land. The landowner additionally excavated near the workshop to extract a level of white sand/soil for construction purposes. Excavations confirmed the location of the older gravel road and revealed the extent of modification of the hilltops, including a cement foundation, later reused by a family who leased the land for residence, although the house was taken down and moved off-site in recent years.

In spite of these limiting factors, project members were able to recover a significant amount of material from the excavations, which included 429 mold and figurine fragments and 3,165 sherds. We partially excavated one deep midden (ARA-3-15 and 16), one looted structure near the river (Operation 2), a second mound atop a hill that had been bulldozed by the paving company (ARA-3-5 to 3-10), and the remaining floor of a probable shrine located about halfway up the same hill facing west (ARA-3-1).

PREVIOUS INTERPRETATIONS

The Pre-Columbian history of occupation in the Cobán plateau is largely unknown, with most extant research based in ethnohistory and beginning around the time of the Spanish conquest (Escobar Reference Escobar1841; Las Casas Reference Las Casas1909; Sapper Reference Sapper1936; see King Reference King1974 for comparative twentieth-century patterns). The Maya here were largely responsible for harvesting the majority of large, green feathers of the resplendent quetzal, an essential symbol of kingship, for the entirety of the Mesoamerican economy (Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019a). In addition, highland Verapaz was known at the time of the Spanish conquest for providing a variety of other commodities—liquidambar, white honey, jasper, sarsaparilla, freshwater shrimp, maguey fiber, alabaster, and cotton (Feldman Reference Feldman1985:78, 94, 103; Gage Reference Gage and Thompson1958:209; Patch Reference Patch2002:25; Saint-Lu Reference Saint-Lu1968; Viana et al. Reference Viana, Gallego and Cadena1955:210; Ximénez Reference Ximénez1967 [1722]:114, 115; Zuñiga Reference Zuñiga1608). Due to the abundance of these commodities, and the proximity to other valuable resources such as cacao, achiote, and salt in the neighboring lowlands of the Northern Transversal and the Polochic, the position of the regional magistrate (alcalde mayor) of Verapaz was one of the most sought-after in colonial Latin America (Patch Reference Patch2002:28–29).

While scholars assumed that the region had similar economic importance during earlier times, there was no direct evidence to support such a perspective during the Classic and Early Postclassic periods. The identification of a glyphic sentence u-na-ka-wa ta-ba JOLOM-mi ko-ba-na-AJAW, u nakaw tab joloom koban ajaw “he attacks Tab Joloom, the Koban Ajaw” on Step 2 from Hieroglyphic Stairway 2 (east) from Dos Pilas (Grube and Schele Reference Grube and Schele1993) might suggest that Koban was a key location from as early as the Classic period (Figure 3). This sentence, dated to a.d. 662, credits the king of Dos Pilas, Balaj Chan K'awiil, with this battle with the Koban polity. We cannot, however, be absolutely sure that the Koban toponym mentioned in Dos Pilas indeed identifies the actual Cobán of the Verapaz. According to Tovilla et al. (Reference Tovilla, Scholes and Adams1960), the place where the Dominicans founded their monastery in a.d. 1544 was already known as Cobán to the local Maya groups. Like many other Maya toponyms, it most likely has a great time depth. Until now, there was little archaeological evidence to assess whether this was the case (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Inscription on Step 2 from the Hieroglyphic Stairway (east) of Dos Pilas, indicating interaction between the site with the toponym “Koban” (Grube and Schele Reference Grube and Schele1993:Figure 1). Drawing by Grube after a drawing by Ian Graham.

Although four archaeological sites were identified atop the Cobán plateau by A. Ledyard Smith in the mid-twentieth century (Smith Reference Smith1955), most of our knowledge of this earlier history came from a single, short, contemporaneous report written by Robert E. Smith (Reference Smith1952). Robert Smith described Late Classic ceramic material recovered from a road-cut that nicked the corner of a mound within city limits at the site of Chipoc (see Figure 1). The modes he described were later identified as part of a larger ceramic sphere that includes archaeological sites in a wide region of the northern highlands—the Purulhá Valley and Los Cerritos Chijoj to the south (Arnauld Reference Arnauld1986, Reference Arnauld and de Hatch1999a, Reference Arnauld and de Hatch1999b; Ichon Reference Ichon1992), Nebaj to the west (Becquelin et al. Reference Becquelin, Breton and Gervais2001), and the Cave of Hun Nal Ye to the north (Woodfill et al. Reference Woodfill, Guenter and Monterroso2012). Such materials are also common to sites beyond the highlands, such as Cancuén, Raxruha Viejo, Sebol, and Salinas de los Nueve Cerros. Here they often appear alongside standard lowland types and the well-defined local ceramic tradition, referred to in the literature as “Transversal” (Woodfill Reference Woodfill2010, Reference Woodfill2011).

The El Aragón ceramic assemblage from the rescue project (described in more detail below), is exciting for several reasons. Not only does it triple the Cobán area ceramic collection with exceedingly well-preserved examples, but it allows us to refine the settlement chronology of the area, as well as documenting interregional ties through the inclusion of non-local materials that were not reported in another near-contemporaneous salvage operation in downtown Cobán (Perla-Barrera Reference Perla-Barrera, Valenzuela and Garrido2018). The new material includes multiple sherds that date to the Early Postclassic period (a.d. 850–1200; e.g., Figure 4), pushing the occupation of the site beyond the collapse of Cancuén around a.d. 803. The material includes at least a few Fine Orange sherds (Figure 4), a ceramic type typical of the Gulf Coast that became increasingly prestigious as a status good in the southern lowlands as trade to the central Petén was interrupted during the early years of the Classic collapse (e.g., Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, Andrieu, Torres, Forné, Barrientos and Wolf2014).

Figure 4. Examples of Late Classic ceramics from the non-excavated collection: (a) Nispero Trichome, (b) Hinojo Negative, (c) Early Postclassic zoomorphic plate support, (d) Altar and Pabellon Fine Orange. Photographs by Sears.

The ceramic figures and molds are identifiable in the “Alta Verapaz” style—referred to as one of the eight “subareas of the Maya figurine tradition” by Rands and Rands (Reference Rands, Rands and Willey1965) for their high quality of artistry. The figures are made with the help of elaborate molds—often with two interlocking mold pieces to create a truly three-dimensional object. Similar smaller-scale figurines have been noted using this manufacturing technique from Chamá, Cancuén, Raxruha Viejo, and Salinas de los Nueve Cerros, but in smaller proportions (Sears Reference Sears2016). The current excavations from Salinas de los Nueve Cerros contain a small collection of this front-back mold production technique associated with an oven feature (Mijangos Panteleón Reference Mijangos Panteleón, Valle, Mijangos, Woodfill and Tox2013). What is strikingly different about the ceramic imagery recovered from the rescue project and the private collection at El Aragón is that there are far more examples of initial manufacturing products here than at other sites in northern Alta Verapaz. At Cancuén, for example, even with its large palace and surrounding sections of elite residences producing intricate jade products, nearly two decades of investigations have recovered only six ceramic figurine production molds (Sears Reference Sears2016). Previous work in the northern Alta Verapaz (unlike what is discovered in Cobán) with ceramic figural portraiture has noted the range of production styles that trend toward what is an acceptable presentation of Late Classic Maya lowland standards (Sears Reference Sears2016). The general pattern that was used in this region was to create ceramic figurines by manufacturing a mold for the frontal design, removing the positive side from the mold, and then building a triangular-shaped ceramic backing that contains a whistle mouthpiece and ocarina holes at shoulder height. This figurine form would indicate a side-seam where the front was joined to the back and has a tripod-support shape. A secondary figurine production design uses joined mold parts (arms, legs, torsos, heads) to build a ceramic humanoid figure whose limbs were arranged apart from the body and supported the figure on two legs. The mold-made triangular-shaped figurine is the common pattern (with site/artist preference of ocarina hole placement at different points on the object; Sears Reference Sears and Insoll2017:224, Figure 11.3). Future work with the private and rescue collections at El Aragón will attempt to discern the valley preferences of imagery, manufacturing sequences, and the range of production variation.

Previous Iconographic and Epigraphic Evidence in the Region

With notable exceptions, the Alta Verapaz region of the Guatemala highlands lacks large stone monumental stelae with inscribed epigraphic information (Rands Reference Rands1968). Among the exceptions are those sites at the most northern designation described by Karl Sapper and Brian Dillon at Salinas de los Nueve Cerros (Dillon Reference Dillon1977; Sapper Reference Sapper1936), La Linterna (Gronemeyer Reference Gronemeyer, Demarest, Torres, Sion and Andrieu2020; Torres and Tuyuc Reference Torres, Tuyuc, Demarest, Torres, Sion and Andrieu2020), and the distinctive Late Classic notched-top stelae at Cancuén (Demarest Reference Demarest2013; Dillon Reference Dillon1977; Maler Reference Maler1908). Another significant epigraphic discovery was the stone box from the Hun Nal Ye cave (Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019a:139–143; Woodfill et al. Reference Woodfill, Guenter and Monterroso2012). Even if monumental inscriptions do not exist in the Alta Verapaz, the presence of uninscribed stelae and altars in various sites, such as Chich'en at San Juan Chamelco (Arnauld Reference Arnauld1986; Smith Reference Smith1955), B'omb'il Pek Ruinas (Woodfill, personal observation), Chikoy (Van Akkeren Reference van Akkeren2012), and Raxruha Viejo (Andrieu et al. Reference Andrieu, Sion, Torres, Demarest, Aldan, Cambranes, Díaz, Estrada, Quiñonez, Saravia, Tox, Arroyo, Salinas and Alvarez2018), is evidence of the existence of this ritual complex in the Verapaz.

Of course, epigraphic rendering is not restricted to only monumental forms. Information pertaining to the political organization within the region has been inferred through assemblages of elite ceramic polychrome vessels with primary standard sequences and mold-made ceramic fragments. Polychrome pottery with hieroglyphic texts was produced in large quantities in Chamá (Butler Reference Butler1940). Elin Danien identifies four style groups in the ceramic material excavated by Burkitt (Reference Burkitt1930) at the sites of Chamá, Chipal, Kixpek, Tambor, Chiutal, and Ratinlinxul (Danien Reference Danien1998). Numerous Chamá ceramics bear dedicatory texts, but many are also decorated with pseudo-hieroglyphs. Another pottery production site where ceramics with hieroglyphic inscriptions were made is Chipoc (Saravia Orantes et al. Reference Orantes, Francisco, Garay, Saravia, Arroyo, Salinas and Álvarez2018; Smith Reference Smith1952). A fourth group of ceramics with hieroglyphic texts is the mold-made pottery from the Cobán and Chajkar region.

Notable among these are the ceramic collections made by Erwin P. Dieseldorff during the height of German interests in the Cobán region at the turn of the nineteenth century (Náñez Falcón Reference Náñez Falcón1970), the Castillo collection at the Museo Popol Vuh, and the donated/repatriated objects within the Fundación Ruta Maya, the so-called whistle boxes. These unique ceramic objects are created from mold-made production techniques that allow the sides of the box and four support feet to include raised imagery (such as ajaw or deity figures), as well as hieroglyphic phrases that fill the middle spaces (Houston Reference Houston2016; Peréz Galindo Reference Pérez Galindo2007). In 2004, Pérez Galindo carried out an inventory of the remainder of the Dieseldorff fragments that were not exceptional enough to be shipped to Berlin and currently reside in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología (MUNAE). In her report, she indicates 13 examples of whistle-box fragments, three that contain examples of the word “Ajaw” or Lord within the script (Pérez Galindo Reference Pérez Galindo2007:Table 2, Design 4, 8, 12, and Figures 20–32). Houston (Reference Houston2016) expands upon this set, combining the MUNAE Dieseldorff pieces with the intact example that is at the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin. He notes that there are deeper levels of kinship-related titles that are within these Terminal Classic examples. While the glyphs on the foot support from the Dieseldorff Berlin example first indicate ownership of the whistle-box (baah tz'am) as the “head person” of the throne, the successive glyph (y-ichaak) denotes nephew or cousin (Houston Reference Houston2016:Figures 2 and 3). This is an unusual reference to courtiers who are not indicated through standard material references on ceramics, stone, or wood. Additionally, Dieseldorff remarked in his own writings that his workers found many ceramic fragments with hieroglyphic inscriptions, including fragments of incised clay “Tonplatte” or “tablets” in places in the immediate vicinity of Cobán, such as Chipolem (Dieseldorff Reference Dieseldorff1931:28, 29), Petet (Dieseldorff Reference Dieseldorff1931:29), Chipoc (Dieseldorff Reference Dieseldorff1926:14), Chajcar (Dieseldorff Reference Dieseldorff1926:22, Tafel 32), Sanimtacá, and Sabalám (Dieseldorff Reference Dieseldorff1926:23). Of his illustrations, Figure 6 from Dieseldorff's (Reference Dieseldorff1931) report, contains an image of a ceramic sherd appearing similar in style and execution to the new ceramic objects with raised glyphs found at the site of El Aragón.

THE 2018 EL ARAGÓN COLLECTIONS

Two different collections of ceramic materials at the valley site of El Aragón were made during 2018. The first was the original discovery of the hidden mound by the landowner (the private collection). The second was from the brief, stratigraphically controlled excavations conducted in July 2018 by members of the Salinas de los Nueve Cerros archaeological project. While the excavated areas lent context, the downside of working with this dataset is that the number of examples with figural forms were fewer in number and highly fragmented, prohibiting a complete understanding of the entirety of the objects. In contrast, the remains from the plowed mound were collected by the landowner while removing dirt to widen the road-cut. This collection contains many programmatically intact, but broken ceramic objects. The material was gathered in large milk-crates, without a record of context or the archaeological standards to retain each specimen or design in separate bags (currently estimated at over 2,000 fragments). There will be many hours spent in the future to rejoin numerous pieces from the private El Aragón collection to determine overall designs and separate modes of production. All these actions will continue for many months during the following season, and hopefully additional design features of the selected examples further discussed will be added.

Briefly, the most common ceramic pottery recovered by the archaeological team represented local Late Classic types. The biggest proportion of the collection consisted of utilitarian wares—unslipped bowls and comales from the Chatillas ceramic group (Chatillas Smoothed and Celidona White types) and zoned red-slipped and unslipped jars (Mozote Red-on-Natural and Cebada Porous). For the decorated ceramics, the Mozote group predominated, from incised white- and grey-slipped cylinders and bowls (Nitro Incised and Chucho Grey Incised) to black/brown-on-white resist ware (Hinojo Negative). The rest of the material was split largely among brown-slipped plates (Chichicaste Brown) and various orange- and red-slipped types (Olola Orange, Escobilla Orange-Brown, Gladiola Red, and Eneldo Red-on-Orange).

The team recovered a small quantity of probable Early Classic material (Chipilín Red), as well as some Early Postclassic zoomorphic plate supports. A small amount of Late Postclassic material was found in each of the operations, predominantly Fortaleza White-on-Red, Manzana Striated, and Mamey Red jars. Imported wares or styles found at the site were largely Late and Terminal Classic and draw from many other parts of the highlands, from the lower Río Negro valley around Los Cerritos Chijoj (Cusulá Black jars and diverse forms and types from the utilitarian Pasaquil group) to the Ixil triangle (Turanza Negative, Chemalá Polished Red, and Bisán Brown Red). Several examples of Altar Orange ceramics point towards lowland connections as well (Alvarado et al. Reference Najarro, Silvia, Castellanos, Lee, Molina Luna, Bárbara, Méndez Salinas and Ajú Álvarez2019), echoing the presence of other lowland types, such as Saxche-Palmar Orange Polychrome recovered from a tomb at Chich'en (Montoya Reference Montoya and Demestre2020:Figure 3).

The Design Features of the Ceramic Plaques

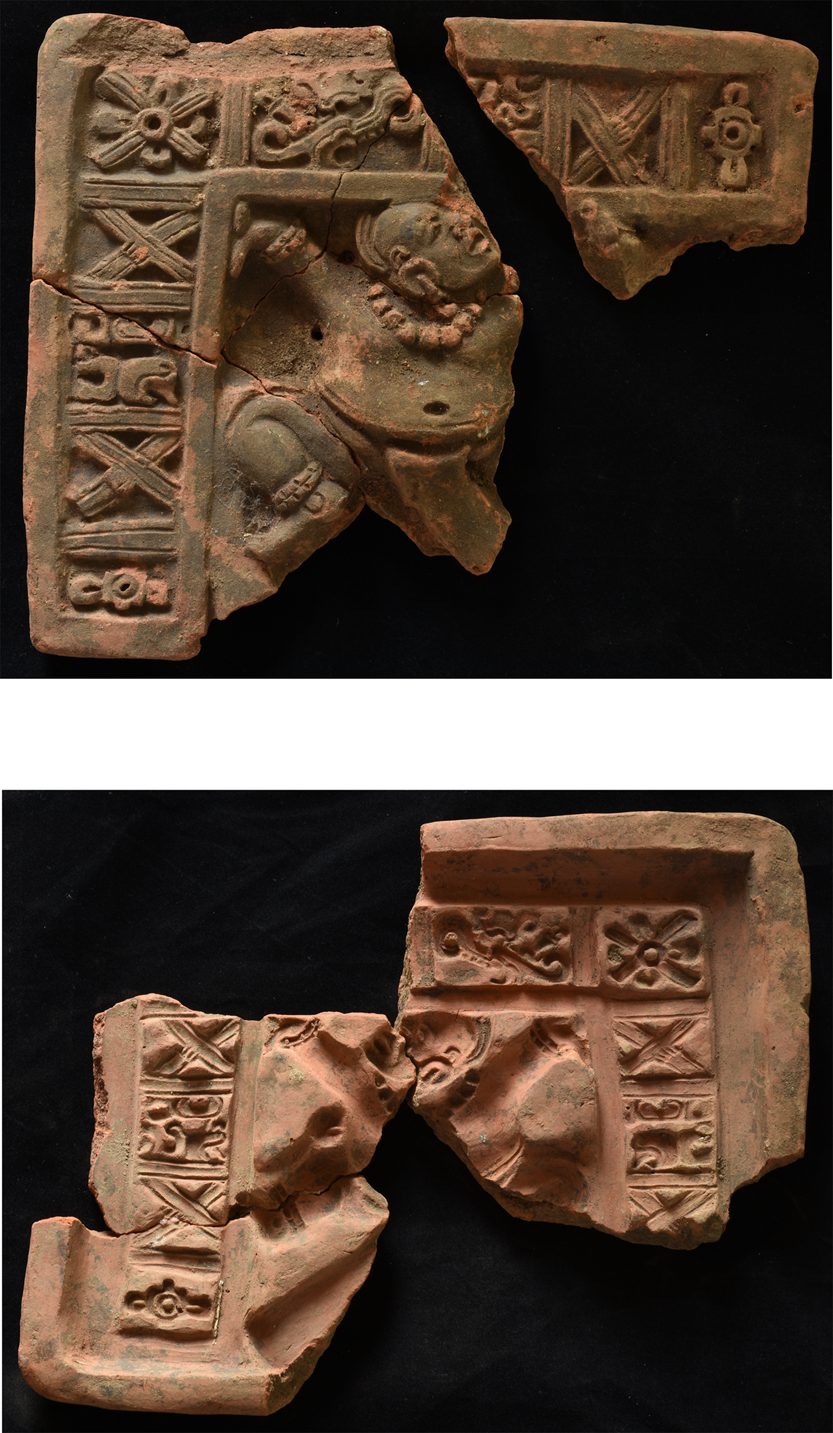

The collection from both El Aragón studies contains production materials (ceramic molds) and the final products that were created for the local ancient constituents. What is new in this corpus of Late-Terminal Classic Maya ceramic remains is that the inhabitants of this valley created rectangular, square, ovoid, and irregular-shaped flat objects that are first to be characterized here as plaques (Dieseldorff considered these objects clay tablets; Dieseldorff Reference Dieseldorff1931:Figure 5). These examples are mold-made, thin-shaped with fantastic designs, and deeply stamped frontally with a flat back. Additional larger examples of ceramic plaques (not discussed in this article) within the original Aragón private collection have appliquéd U-shaped ceramic attachments, with centered hollow apertures placed in the back of the object to allow for a string to be attached for suspension. These particular forms could be easily suspended from thatched roof supports or a post with a banner crosspiece.

The announcement of the initial discovery in North American news made the 2019 July/August issue of Archaeology and included the illustrations of a misidentified fragment of a ceramic plaque that contained molded glyphs organized in two columns on the right side of the object (Brown Reference Brown2019:16). The brief summer 2019 laboratory season allowed for more design features to be attached to this example. The ceramic pieces have individual inventory numbers that were assigned by the first author to discern what was private collection (FA#s) versus those found from the July 2018 excavation season (AGN#s).

The two most important ceramic plaque fragments originate from the private collection, FA0256 and FA0257 (Figure 5); they are similar in layout and with two columns of glyphs, but are divided in appearance in a left/right arrangement. Both examples have the potential in the future to have additional pieces match as the laboratory analysis continues, but the interior image attached to both glyph panels consists of thin, flat deity visages that are left or right profiles from the two glyph columns. There is an additional intact copy of the right profile of the deity face (FA0270, Figure 6, albeit with a square earspool) that is a potential exemplar of what is the design feature to the left of the glyph panel in FA0257. The goal is to find and attach additional corresponding glyph columns next season so that there is another right profile example to demonstrate production capabilities. Hypothetically, there would be a similar deity face attached to FA0256 (as indicated by the upper portion of the headdress).

Figure 5. The ceramic plaque fragments (left) FA0256 (h. 21 cm × w. 7.8 cm) and (right) FA0257 (h. 16.4 cm × w. 17.5 cm), both indicating the Long Count discussed in the text. Photographs by Sears and drawings by Luis F. Luin.

Figure 6. From the private collection, a right profile example (FA0270; h. 18.4 cm × w. 12.5 cm) of the deity visage that is not fully present in FA0257. Photographs by Sears and drawings by Luis F. Luin.

The representation of the deity is an amalgamation of three deities, the Sun God, the Fire God, and the Wind God. In Taube's analysis of the Early Classic Stela 31 of Tikal dated at a.d. 445, the belt of ruler Sihyaj Chan K'awiil combines aspects of these three gods in order to meld fundamental beliefs concerning life, death, and rebirth (Taube Reference Taube, Grube, Eggebrecht and Seidel2001:266–267, Figure 418). The Late Classic example from El Aragón contains the same markings (Figure 6)—the pupil of the day sun, the eye surrounded by the twisted “cruller” line forming the night sun, the truncated flower sign above the eye to signal the Wind God, and the elongated serpentine nose of the K'awiil. The X-incised earspool is an elite feature found in other examples of ceramic figures in the Aragón collection. The recent El Aragón deity visage is not the singular example from Cobán. Pérez Galindo records a similar ceramic example from the Dieseldorff collection at MUNAE. She designates the object as a “flat face” that appears to be similar in design to the El Aragón piece; however, this example contains more cut-outs of smoke/breath scrolls on the right side of the design and a truncated face. Unfortunately, the Dieseldorff example is incomplete without the corresponding right-sided glyph composition (Pérez Galindo Reference Pérez Galindo2007:Figure 8, MUNAE drawer 96-3). The two different visages add an interesting west/east Cobán directional pattern in documenting elite imagery within the valley. Additionally, a different ceramic cut-out deity visage was recovered in 1894 at the site of Chich'en, a colonial finca at the southern outskirts of the city of Cobán, and found its way to the University of Ghent collections (Montoya Reference Montoya and Demestre2020:79, Figure 3, fifth row, first object on left).

When considering other potential functions of the mold-made ceramic designs, the cut-out features of the ceramic plaques FA0256 and FA0257 do not assist elegantly in creating a ceramic vessel or a whistle-box, since producing four copies of the same imagery and joining them together would allow liquids or air to escape. Therefore, the arrangement of the objects may give a better understanding towards a different fit within the ancient community. Since the amalgamated deity visages can be arranged in such a way that they are looking at each other, and the imagery is flanked by the same glyph column design, new potential functional arrangements could be imagined. The thin objects could have been engaged into a stucco façade in a left–right manner on opposite sides of an ancient exterior doorway. Another speculative arrangement could place the two pieces in a side-by-side fashion on either side of an entrance (see Figure 5). Both design arrangements would indicate the accomplishments of this ancient elite family to all who passed through the public doorway of the home. This functional hypothesis of the El Aragón plaques would be considered minor in scale in comparison to the incised stone tablets engraved into palatial architecture found at sites such as Palenque. An explicit example is the stone oval tablet of Lady Sak K'uk and her son K'inich Janaab Pakal (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:161).

Another plausible interpretation is that the plaques (especially the suspended variety) were part of an interior altar setting for a wealthy household in the area. Domestic altars are both an ancient and current feature within Maya households. They serve as an important ethnographic reference of similar religious elements in pre-Hispanic times. Ancient and modern Maya usage of altars includes material items that form the ritual assemblages imbued with defining the most revered space in traditional Maya houses. Modern wooden crosses imbued with ancient interpretations hold their places next to figures of local saints, along with pre-Hispanic ceramic sherds, figurine fragments, lithic materials, stalagmites or stalactites coming from sacred caves, and other kinds of culturally significant materials (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Scott, Neff and Glascock1997; Brown Reference Brown2000; Schele and Freidel Reference Schele and Freidel1990). From the recent ethnographic information detailing Maya ritual practices, there is room to interpret that many of the ceramic objects found in El Aragón could correspond to similar ritual patterns in ancient times. The painted figures of saints on modern altars can easily be seen as replacing the ancient ceramic plaques that depict gods and other supernatural beings that were once produced in the central region of Cobán, and later distributed to its neighboring areas.

If modern altars can be used as some exemplar to ancient traditions, they are usually placed in a corner of the house or close to the center of the house, next to the main and largest wall, facing the front door in the case of one-room houses. Most of them are composed of the following elements: (1) a wooden table, which serves as the base for the altar, where all the objects are placed; (2) censers and/or candleholders, which may or may not be placed on the table, as sometimes they lie in the area in front of it, which is specifically designated for the burning of offerings, which include but are not limited to: candles, incense, and ocote; and (3) sacred objects, which come in different forms and belong to various traditions, and could include saints’ effigies (ceramic and wooden), prints of saints, wooden crosses, archaeological artifacts (e.g., ceramic sherds, obsidian flakes, vases), natural objects (e.g., stalagmites, rock crystals), photographs of family members (including deceased relatives), and recently, objects alluding to Maya spirituality and calendars (e.g., print Maya calendars) (Deuss Reference Deuss2007:39–41, 50–52; La Farge Reference La Farge1947:114–117; Siegel Reference Siegel1941:69–70; Termer Reference Termer1957:162–164, 170, 181–182). It is useful to highlight that the nature and shape of the altars vary from household to household, meaning that there is no single uniform typology that can be applied to all of them throughout the Maya area, but most of them conform to the three elements mentioned above. The domestic altars in pre-Hispanic times must have followed a quite similar pattern, albeit with the absence of all the Christian imagery and modern Maya print calendars. Today, in many of the most traditional regions in Guatemala, like the Cuchumatanes area (Deuss Reference Deuss2007) or the Momostenango region (Tedlock Reference Tedlock1982), there is a widespread presence of this kind of domestic sacred space.

Another production aspect from El Aragón is that the molds that make the positive parts of the large ceramic idols, figurines, plaques, and whistle-boxes are largely represented in both the private and rescue collections. At times, the broken molds match the positive parts, indicating that the valley between the two hills was used as a manufacturing zone. The two molds FA0258 and FA0259 (Figure 7) are fragments that match portions of the glyph panels in FA0256 and FA0257. Specifically, FA0258 is a mid-section match to FA0256, including additional three glyph rows that are not found at the end of the positive example. FA0259 is also a mold match to FA0257, which contains the second, third, and fourth row of glyphs.

Figure 7. The manufacture molds (top) FA0258 (h. 22.7 cm × w. 7.8 cm) and (bottom) FA259 (h. 12.5 cm × w. 8.7 cm) that match the positive ceramic plaque fragments (FA0256 and FA0257) from the bulldozed area at El Aragón. Photographs by Sears and drawings by Luis F. Luin.

The Epigraphic Features of the Ceramic Plaques

For a long time, evidence of the existence of hieroglyphic texts in the Maya highlands of Guatemala has been restricted to just a couple of sites, such as Kaminaljuyú or El Portón (Fahsen Reference Fahsen, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010), even though evidence of writing in the latter is not completely clear. During the Late Preclassic, monumental texts appear in different sites along the Pacific littoral (Tak'alik Ab'aj, El Baúl, Chalchuapa, El Trapiche) which made use of the same iconographic and sign repertoire as early inscriptions from the central lowlands, suggesting the existence of intellectual networks that somehow connected the two areas and allowed for the flow of information and technologies between them, including the notion of a writing system. The lack of written texts in the highlands is possibly only an accident of limited archaeological research.

Although it seems that the elites of some highland Maya polities were acquainted with the Maya writing system during the Late Classic, as is demonstrated by the existence of painted ceramics presumably coming from the Ixil region, like the Fenton Vase and other pieces by the same artist or workshop (Beliaev Reference Beliaev2005; Saravia Orantes et al. Reference Orantes, Francisco, Garay, Saravia, Arroyo, Salinas and Álvarez2018), the lack of certainty about provenance makes it hard to claim a highland origin for many of them, a fact that is especially troublesome when associated with hieroglyphic texts that are not usually present in the ceramics from that region. The discovery of a series of ceramic fragments that includes at least some hieroglyphic texts in an archaeological context in the Finca Aragón, Cobán, Alta Verapaz has proven pivotal to demonstrate the fact that at least in the last centuries of the Classic period, the highland Maya from the bordering regions to the lowlands did actually acquire some literate knowledge of the Maya writing system, maybe as the result of the movement of lowland Maya populations to the region. It is likely that the Alta Verapaz region always represented a transcultural contact zone between the highlands and lowlands, where populations from both regions interacted for a long time. The varied collapse cycles of the Classic Maya polities in the lowlands to the north certainly intensified migrations of populations.

There is a notable set of at least five ceramic fragments that include hieroglyphic writing coming from Finca Aragón: FA0256, FA0257, FA0258, FA0259, and AGN036 (Figure 8). There is another fragment containing hieroglyphic elements, FA0253 with its corresponding mold (FA0269), but the arrangement is used as part of the iconography of a celestial band and therefore the symbols are considered associated with the sky—not as actual writing (Figure 9). The five fragments mentioned above each contain one extant hieroglyphic text that repeats the same information throughout them all. It corresponds to a date in the Maya Long Count system (Table 1) and is actually the first one ever registered in the highlands of Guatemala. The date is written using the so-called Head Variants for the periods and numbers in the date. A comparison of the molds and the fragments of the hieroglyphic panels that emerged from them leave no doubt that they were all made from the same template. None of the fragments contains all the components of the original. Nevertheless, the original text can be reconstructed by comparing the different fragments, since the hieroglyphs of the fragments overlap (Figure 8). If all the fragments are put together, the hypothetical template can be reconstructed. The template was a Long Count date consisting of six hieroglyphs arranged in a single column (1–6). Both the coefficients of the date and the periods are written with head variants; in the case of the period Winal, likewise as a full-figure variant.

Figure 8. Illustration indicating the overlap of epigraphic information amongst the ceramic examples. Drawings created by Nikolai Grube and Luis F. Luin. Photographs by Sears.

Figure 9. Ceramic plaque fragments (top) FA0253 (h. 19 cm × w. 20 cm) and (bottom) the matching mold FA0269 (h. 21 cm × w. 21 cm), indicating a celestial band with various glyphs used as symbols representing elements of the sky. Photographs by Sears.

Table 1. Reconstructive transcription/transliteration/translation of the original inscription.

The date begins, as usual, with an Initial Series Introductory Glyph (1). A calligraphic peculiarity is the substitution of the usual T121 superfix, consisting of three little hooks, by a sign which, although also three-part, is otherwise clearly different from the usual superfix found on top of the ISIG. Under it is usually the patron of the month, flanked by two ka-syllables (Thompson Reference Thompson1950:Figure 23). The two ka-syllables are indeed present, but the patron of the month is only a circle and therefore cannot be assigned to a specific month. The main sign of the hieroglyph is the sign T548 HAAB in a simplified version, in which the lower half of the sign seems to be missing and only the upper part appears with two or more horizontal bars. Such reduced Haab variants can be found in other texts of the Terminal Classical period (Sacchaná Stela 2; Chichén Itzá, Temple of the Initial Series) and also appear in the El Aragón Long Count date in four (the Tun period of the Long Count) and in the head variant of the number 15 in A5. The three elements below the Haab sign are regularly present in the ISIG (Thompson Reference Thompson1950:Figures 23–35, 34–37, 34–38). The absence of the month patron in the center of ISIG leaves the impression that it is a kind of “neutral” introductory hieroglyph without any reference to a particular month, similar to the ISIG on early monuments from Copán (Stela 15; Motmot marker; Margarita step).

In Glyph 2 there is the period 10 Bak'tun, written with the head variant for the number ten, a skull, and the head variant for the Bak'tun period, which was read PIK HAAB and shows an avian head. The following unit is one K'atun. The number one JUUN is written with the head variant showing the young, tonsured maize god, whose characteristics include a long curl of hair that frames his face. The sign was the portrait of the maize deity known as Juun Ixiim and could therefore communicate both values, juun “one” and ixiim “maize” (Zender Reference Zender2014:5, 9). The sign for the K'atun period, which was read WINIK HAAB, consists of a bird's head with the same sign on its head that appears in ISIG. In well-executed classical texts, the central element of this sign is the so-called Kawak sign (T528), which, here, is replaced by a simple circle.

The Tun period in Glyph 4 has a head variant as coefficient, the identification of which is problematic. The head is that of a male with an earspool and a round bead in his forefront; the lack of any clearly identifying attributes leaves the identification of this character ambiguous, but because of the lack of any other defining characteristics of the numbers between one and nine, it can be deduced that it should be a head variant for number three or eight, which represents a youthful man who carries an earspool. It is evidently not a number between 13 and 19 since it lacks the bone mandible characteristic of those numbers (compare with the examples in Thompson Reference Thompson1950:Figures 24 and 25). The animal head that accompanies the human portrait can be easily identified as a form of the Waterlily Serpent, which is used to annotate the tun (haab) period in various examples (compare with QRG St. D, west text: A07–B08 or QRG Mon. 26: A4–B4).

In Glyph 5 we encounter the head variant of the number 15, which consists of the head for the number five in combination with a fleshless lower jaw that marks all numerical values from 13 to 19. Curiously, the WINAL glyph is the only one that is registered in a full-figure form throughout all the examples, with slight variations among them (compare FA0256 and FA0257), but always representing a seated, animal-headed creature with a collar of round beads (Figure 8). The differences in the heads of these creatures could be the result of the addition of minor details by distinct artisans before the pieces were finally fired.

At the last position of the column is the hieroglyph 12 K'in. The head variant for the number 12 is a youthful head with the sign for sky, CHAN, on its head (Thompson Reference Thompson1950:Figure 25, Examples 3–7). It is combined with the head variant for K'IN “day,” which shows the head of the sun god with a large, prominent nose, protruding front teeth, and an oversized eye. Attached to it is the phonetic complement -ni for K'IN-ni. This small detail is of great importance in that it gives us an indication of the linguistic identity of the scribes of this date. They must have been Cholan speakers and not speakers of highland languages, where the word for day is *q'iij. The scribes of this date who lived in the region of present-day Cobán used either Cholan as their written language, even though they had a different first language, or they were scribes from the lowlands who had come to the highlands of Verapaz and thus brought their mother tongue with them. This interpretation is further suggested by the Cholan vocabulary detected on the ceramic thrones from the Dieseldorff collection by Houston (Reference Houston2016). The inscriptions on the painted ceramics in the Nebaj style and from the Chamá region in the highlands are clearly based on Cholan, although they show a certain infiltration of vernacular vocabulary, probably reflecting proto-Ixhil and proto-K'iche' (Beliaev Reference Beliaev2005; Saravia Orantes et al. Reference Orantes, Francisco, Garay, Saravia, Arroyo, Salinas and Álvarez2018). It seems that the Cobán region, and the northern highlands in general, had become a new center of power in the aftermath of the fall of Cancuén and the population movements associated with the collapse of the neighboring polities in the lowlands.

Depending on which number is expressed by the head variant of the Tun period, the following alternatives are possible for reading the date:

10.1.3.15.12 6 Eb 15 Mak September 18, 853

10.1.8.15.12 12 Eb 10 Kej August 23, 858

The dating confirms the ceramic chronology that is demonstrated for the sherds of the excavated El Aragón collection. Unusual with regard to the date is the complete lack of further information. There is neither a Calendar Round date nor a Secondary Series which otherwise accompany Long Count dates. It is quite remarkable that we learn anything about the event that made this day so critical that it became immortalized. While the plaques probably registered a historical event, the continued research and future discovery of hieroglyphic texts in the area may provide contextual clues to the larger history of the region.

All in all, the Long Count on the El Aragón ceramic plaques is one of the few Long Count dates from the 10th Bak'tun and is therefore a notable document from the Late Classic period, despite the lack of historical context. It is interesting that of the 15 existing Long Count dates from the 10th Bak'tun, five come from the western/southern peripheries of the lowlands (El Aragón, Sacchana, Tonina) and six are from places in Campeche and the northern lowlands (Oxpemul, Ek Balam, La Muñeca, Chichén Itzá). Perhaps this observation reflects the conscious withdrawal of the surviving scribal communities and intellectuals to regions of the Maya world less affected by the apocalyptic processes of the collapse. (The fifteen Long Count dates from the 10th Bak'tun are: Xunantunich Stela 9 (10.0.0.0.0), Oxpemul Stela 7 (10.0.0.0.0), Ek Balam Column 1 (10.0.0.0.0), Xultun Stela 8 (10.0.0.0.0), Xultun Stela 3 (10.1.10.0.0), El Aragón Long Count (10.1.3/8.15.12), Walter Randall Stela (10.1.14.0.0?), Sacchana Stela 1 (10.2.5.0.0), Chichén Itzá, TIS (10.2.9.1.9), Sacchana Stela 2 (10.2.10.0.0), La Muñeca Stela 10 (10.2.10.0.0), La Muñeca Stela 1 (10.3.0.0.0), Xultun Stela 10 (10.3.0.0.0), Tonina Monument 158p (10.3.12?.9.0) and Tonina Monument 101 (10.4.0.0.0). For an extended regional list of Long Count dates, see Ebert Reference Ebert, Prufer, Macri, Winterhalder and Kennett2014:342–344, Table 1.)

DISCUSSION

The El Aragón plaques will continue to be of value in future interpretations as they have been sampled for neutron activation analysis within a larger study that incorporates ceramic sherds from the site. The chemical patterning will hopefully assist in establishing the continuities in the valley versus interregional patterning. For the moment, these new examples demonstrate different aspects. The collections indicate that the ancient Maya in this region had a knowledge base that used a new mold manufacturing technique to create a different version of ceramic design and functional intent. Unlike Pabellon molded-carved vessel molds, or figurine mold production in other parts of the southern Maya lowland region, which are deeply concave-shaped in mold design (Halperin Reference Halperin2014; Sears Reference Sears and Insoll2017; Triadan Reference Triadan2007; Werness-Rude Reference Werness-Rude2003; and see Rice Reference Rice2015:138, for an explanation of manufacturing methodology), the new technique to create the El Aragón plaques results in relatively flat and/or shallow designs. This new form of manufacturing indicates that there is an aspect of production tradition that is different from what was occurring in communities in the Late Classic northern Alta Verapaz region, as well as along the Pasión/Usumacinta riverine systems. This new mold-making design may be a reflection of functional preferences, as elites within the Cobán valley could display the plaques in public venues by placing the objects within architectural features (such as stucco walls of homes or ritual spaces) and/or have the ceramic plaques suspended from roof rafters or interior house altars.

The inscriptions and designs contained in the El Aragón plaques are a reflection of this highland community's connections to the larger concepts and standards within the greater Maya region. The appearances of the conflated god visages and the use of iconographic symbols to illustrate the sacred sky as an architectural element are found within other material references in the Maya region.

The glyphs on the El Aragón plaques are an example of changing scribal practice towards the end of the Classic period. The production of text in molds is a widespread phenomenon during the Late Classic period across much of the Maya lowlands, particularly in relation to the three most widely documented types of molded-carved ceramics, Pabellon, Sahcaba, and Ahk'utu' (Bishop and Rands Reference Bishop, Rands and Sabloff1982; Foias and Bishop Reference Foias and Bishop2013; Helmke and Reents-Budet Reference Helmke and Reents-Budet2008; Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975:32; Smith Reference Smith1955). Molding technology made mechanical reproduction of texts possible. This enabled potters who were themselves illiterate to produce objects with texts. The fact that such texts circulated widely in the Late Classic and that moreover they were found in richly decorated elite tombs suggests that such mechanically produced texts were held in the same esteem as hand-painted or carved artifacts (Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2018:301). The mechanically reproduced texts have a wider distribution and therefore a less specific local content. Apart from a few exceptions, the texts made in molds do not represent concrete historical events (Helmke Reference Helmke2001:21; Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto2018:307–308). Pseudo-glyphs are very common on molded ceramic vessels and indicate that writing was considered to be of high prestige even by individuals who were not familiar with the writing system (Calvin Reference Calvin2006).

With regard to the reproduced Long Count date on the El Aragón plaques, we can assume that the date itself and the event associated with it were probably less critical than the mere existence of script, which was associated with prestige and courtly culture. This can be further deduced from the fact that on two of the fragments (FA0256 and AGN036A) the date is only incompletely reproduced. On FA0256, the hieroglyphs are arranged so that the last two periods are at the top, followed by the ISIG, the Bak'tun, and the K'atun. Fragment AGN036A is modeled so that a frame is visible above the Winal hieroglyph, cutting off the four preceding hieroglyphs. Obviously, the incompleteness and rearrangement of the glyph sequence has not diminished the intrinsic value of El Aragón plaques for their users.

The El Aragón plaques offer key insights into the writing practice in a region where otherwise inscribed artifacts are rare. The mechanical reproduction of texts seems to have been more widespread in the peripheral and non-writing regions of the Maya world (for example, in Lubaantun in Belize, Tenam Rosario, Los Cimientos, and Lagartero in Chiapas, Zaculeu in Huehuetenango, and Acasaguastlan in the Motagua Valley), perhaps as a way to participate in the highly prestigious courtly culture of the lowlands. In these peripheral areas, people from the lowlands met and interacted with those from the highlands. El Aragón could have been such a meeting place, a place where Chol speakers from the lowlands interacted with people from the highlands, either in the context of economic interaction, or as a result of migrations into the valley, as has been examined extensively from the colonial-rendered mythologies (van Akkeren Reference van Akkeren2012).

Two notable facts about the El Aragón texts need to be highlighted: they have the first Maya Long Count date ever recorded in the Maya highlands, and their clear archaeological provenance makes them unique in helping to provide a better context for many similar pieces that have been previously brought to light concerning the ritual patterning used within the valley. The new objects recovered from El Aragón reinvigorate and create a dialogue of comparison to similar ceramic material found in early twentieth-century collections that are currently curated in Guatemalan and international museum collections. These new design features, in relation to museum examples, widen the understanding of the diversity of design and the regional context within the ancient Cobán system.

CONCLUSION

One aspect of the new ceramic and figural material is that residents of El Aragón were closely tied to major trade nodes and economic centers in the southern lowlands. Chamá was located at a strategic “choke point” along the Chixoy River, where any canoe traffic would have to portage a dangerous set of rapids (Woodfill et al. Reference Woodfill, Valle, Burgos, Carcúz, Luna, Mijangos, Ortíz, Urquizú, Velásquez, Wolf, Arroyo, Salinas and Rojas2014). Salinas de los Nueve Cerros was located atop the only non-coastal salt source in the Maya lowlands and was a major production center for salt, salted fish, and a variety of agricultural goods (Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019a; Woodfill et al. Reference Woodfill, Dillon, Wolf, Avendaño and Canter2015). Cancuén was located near the headwaters of the Pasión River and was the largest producer of jade objects in the Maya world (Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, Andrieu, Torres, Forné, Barrientos and Wolf2014). As a result, it appears that all of these polities were closely allied during the economic florescence of the region, and the reflection of shared imagery, hieroglyphic knowledge, figural mold tradition, and prestige ceramics would have served as a mechanism to cement these alliances.

As lowland society declined, it appears that elites in the peripheral regions of the Maya world obtained greater influence and access to trade and communication routes. This process can be observed on the Cobán plateau, whose residents began to use lowland symbols of elite power, such as hieroglyphic inscriptions with Long Count dates. The Cobán plateau and much of the northern Verapaz had been zones of intense contact with the Maya lowlands well until the colonial period. These contacts are manifest in ceramic modes/styles, shared imagery, lithic materials, and a variety of perishable goods (e.g., salt, achiote, quetzal feathers). The intense interaction between Ch'olan and Q'eqchi' speakers has left traces in Q'eqchi' vocabulary, especially that regarding cultural-specific content (Justeson et al. Reference Justeson, Norman, Campbell and Kaufman1985:9–10). The linguistic influence, however, was reciprocal, for as Gates notes in his commentary concerning Morán's Manche-Chol manuscript, the Manche-Chol word for Huipil was pot, a word originating from Q'eqchi', and perhaps an indication that the Q'eqchi' traded in weaving and fabrics (Morán Reference Morán and Gates1935).

Much like the Gulf Coast iconography added to stelae at Altar de Sacrificios and Seibal (Graham Reference Graham and Patrick Culbert1973), foreign traits were incorporated into local modes of expression, here typified by portable, mold-made ceramic objects. Although Aragón appears to have been abandoned before a.d. 1000, material from nearby sites recovered by Arnauld (Reference Arnauld1986, Reference Arnauld, Rice and Sharer1987, Reference Arnauld1990), and observed in private collections by Woodfill, lacks the lifelike figurines, painted vessels, and hieroglyphic texts found within the nexus of the current city of Cobán, suggesting that subsequent communities focused their attention on maintaining alliances with other parts of the northern highlands.

This shift to highland-style material culture was seen in the adjacent southern lowlands as well. Postclassic material recovered in caves in the Candelaria system and around Salinas de los Nueve Cerros was exclusively in northern highland style (Woodfill Reference Woodfill2010, Reference Woodfill2019a), illustrating the extent to which the political economic core and periphery reversed after the Classic collapse. As recorded in colonial period documents, the Transversal communities that survived the collapse (or formed in its wake) were essential largely as producers of cacao and achiote for the booming highland markets (Caso Barrera and Aliphat Fernández Reference Caso Barrera and Fernández2006, Reference Caso Barrera and Fernández2012; Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Van Akkeren Reference van Akkeren2012; Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019a). The Cobán plateau likely served as a broker for many of these goods, even as it continued to provide the quetzal feathers that made its residents wealthy and powerful (Feldman Reference Feldman1985).

RESUMEN

El descubrimiento inicial de un taller de producción cerámica en el terreno de un valle al este de Cobán, la capital del departamento de Alta Verapaz, en Guatemala, ha reavivado el interés por explorar las asociaciones político-económicas interregionales al interior de estas comunidades mayas. Existe un mosaico de rastros de información proveniente de las colecciones de los museos y de las exploraciones previas de principios del siglo veinte relativas a la zona del valle de Cobán que ayudan a comprender mejor la historia de la región. El inicio de excavaciones por bulldozer en el sitio de El Aragón durante febrero de 2018, cuando el propietario del terreno estaba preparando sus tierras para proyectos de construcción, resultó en la recolección de productos cerámicos provenientes del taller cerámico instalado antiguamente en la zona, que más tarde dio lugar a las subsecuentes excavaciones de emergencia por parte de los arqueólogos para recuperar información contextual adicional de las piezas.

Este artículo documenta el descubrimiento y el establecimiento del nombre de una nueva tipología de cerámica que tiene diseños figurativos. Las placas de cerámica tienen información epigráfica excepcional ya que mencionan la única fecha de Cuenta Larga que se conoce hasta la fecha en esta región (correspondiente al 853 ó 858 d.C.). Desde la temporada inicial de análisis en laboratorio, los tiestos de cerámica provenientes de las excavaciones corroboraron esta fecha por la tipología general. Las placas de cerámica también forman parte de una técnica de fabricación única que comienza con un molde plano y poco profundo, para crear con él el diseño de la deidad en relieve y la información epigráfica que se encuentra en el frente de la pieza. Desde el punto de vista de la producción, esta es una preferencia que no es un patrón que se encuentre en las comunidades del norte de Alta Verapaz. Sin embargo, las imágenes y la información que se presentan indican que los antiguos mayas que residían en este valle también conservaban los estándares de presentación de la élite y la información ritual de sus conexiones con las Tierras Bajas.El descubrimiento reciente de un antiguo taller de producción de cerámica del clásico tardío en el terreno de un valle al este de la actual cabecera departamental de Cobán en Guatemala revela nuevas formas de cerámica y proporciona nuevos datos sobre la cronología regional. Entre los restos hay fragmentos delgados, hechos de molde, identificados como placas de cerámica que tienen información epigráfica que proporciona una fecha de Cuenta Larga por primera vez en la región de Alta Verapaz. Estos datos se correlacionan con las secuencias cerámicas preliminares y ayudan a comprender las interacciones político-económicas que se produjeron en un momento de colapso social en la región sur de las Tierras Bajas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their appreciation for their inclusion with the efforts to preserve and interpret the collections that were discovered on the Archila homestead. Future directions will hopefully create a center that will assist with the understanding of ancient culture and natural history within the region. Foundational and administrative support was assisted with a RAPID-NSF grant (#1840898), the Alphawood Foundation, members of the Salinas de los Nueve Cerros project, Winthrop University, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology. Academic efforts would not have been possible minus a supportive student grant from the DAAD–German Academic Exchange service. Additionally, the authors wish to acknowledge the swift administrative assistance from members of the Departamento de Monumentos Prehispánicos y Coloniales; the time between rescue and research could have been further delayed without the support of this cultural institution. This article is enhanced by two strong reviewers; we are grateful for their time and objectivity during the mid-stage efforts towards publication.