In early 1515, a small Spanish expedition set sail for the province of Cumaná, located along the coast of what was then called Tierra Firme (an area spanning much of present-day Central and South America). Nominally, the squadron, led by Spanish scribe Gomez de Ribera, was sent to punish a group of “Carib” Indians who had recently attacked and killed two Spaniards on the small island of San Vicente.Footnote 1 Once caught, these “Caribs” would be enslaved and sold in the markets of Española, Puerto Rico, or Cuba. Caribs, though speakers of the Arawakan language, were inhabitants of the Lesser Antilles and were likely culturally and politically distinct from the Taíno of the Greater Antilles.Footnote 2 Inhabitants of the Lesser Antilles first received the ethnic label of Carib during Christopher Columbus's second voyage in 1493. Over time, Europeans exacerbated the pre-Columbian divide between Caribs and Taínos, creating a colonial dichotomy that helped the Spanish to expand the indigenous slave trade. By the third decade of colonization, or the time of Ribera's expedition, the Spanish had begun labeling all rebellious Indians as Caribs or cannibals so as to legally enslave them.Footnote 3

Whether or not Ribera and his crew reached San Vicente and attacked or punished the group of Caribs in question remains unclear. However, we do know that in early 1515 they anchored off the coastline of present-day Venezuela, near Cumaná, within the territory controlled by Dominican friars. There, Ribera made contact with the indigenous peoples of the area, inviting a group of 18 to come aboard his ship to engage in trade. At this point, Ribera should have realized that the Indians he had on board his vessel were connected with the friars, as they all spoke at least some Spanish and trusted that the Spanish merchants meant them no harm.Footnote 4 It is likely that the Indians believed that Spanish slavers would leave them alone, so long as they stayed within the bounds of the recently established Dominican missions. However, this was not the case.

Instead of trading with the 18 Indians, Ribera ordered the anchor lifted and the sails hoisted, taking the Indians prisoner. He and his crew then set sail for Española where he quickly sold his captives to various judges and encomenderos, all of whom conveniently ignored the fact that Ribera did not possess the license required to purchase or take Indian slaves from Tierra Firme.Footnote 5 Although Ribera's was only one of many illegal slave raids for which little or no documentation remains, this raid was an exception because one of the captives was the cacique don Alonso. A native of the Paria peninsula, Alonso had developed a close relationship with the friars over the time since their arrival in 1514. Additionally, he had been baptized—hence the Spanish name and title—and therefore could not be enslaved according to the laws of the Indies. It was this trust and friendship that Ribera and his men took advantage of to lure the cacique, his wife, and 16 of his subject Indians aboard their ship.

Ribera's actions damaged not only don Alonso and his family but the Dominican mission as well. The Dominican friars of Tierra Firme depended upon the friendship and cooperation of indigenous leaders like Alonso for the mission's support and survival. With his capture, the friars lost both an important ally and the support of much of the local indigenous population. Many Indians even believed that the friars had helped or at the very least sanctioned Ribera's slaving expedition. Realizing their precarious situation, the friars immediately dispatched a letter to Pedro de Córdoba, the Royal Inquisitor of the Indies and a Dominican friar living in Santo Domingo. In the document, they demanded the return of Alonso and his family within four months, explaining that they had been enslaved illegally. The friars pleaded not only for the freedom of the Indians, but for the safety and survival of their mission in Tierra Firme.Footnote 6

The friars were right to be concerned. Despite denunciations of Ribera's actions by Córdoba and other religious officials in Española, don Alonso and his people were never returned to Tierra Firme.Footnote 7 In fact, their fate is unknown. More than likely, they all perished within a few months of their enslavement in the gold mines or burgeoning sugar plantations of the island.

With Alonso and his family suffering in captivity in Española, the Indians of Tierra Firme grew more and more frustrated with the friars, especially as slave raiding continued.Footnote 8 Eventually, the tension exploded into an attack. What exactly transpired is a mystery, but we do know that by mid 1515 the Dominican friars Francisco de Córdoba and Juan Garcés had been murdered by the Indians of Tierra Firme.Footnote 9 Whether the attack was meant to avenge the taking of Alonso, as Pedro de Córdoba argued, or was carried out by a different group is uncertain. Some claimed that it was “Caribs” from the interior who attacked the vulnerable mission.Footnote 10 Either way, the Dominican experiment ended in a flurry of violence within only a few months of its founding. And despite several more efforts in the following decade, the other missions planted in Tierra Firme would meet a similar fate.

Although several other factors contributed to the failure of the settlements, it was the growing Indian slave trade that made the survival of the missions impossible. With slave raiders and merchants (both legal and illegal) regularly assaulting the region, the friars were unable to create and maintain stable relationships with Tierra Firme's indigenous inhabitants. Seeking safety from the slavers, some fled the coast, and consequently the missions, while others were enslaved and shipped to the Greater Antilles. The Indians who remained demonstrated their frustration by assaulting the very friars who tried to protect them.

A Window into the Developing Spanish Empire

By the third decade of colonization, the Indian slave trade was one of the most profitable and fastest-growing economies of the Spanish Caribbean. Its importance can be seen in the fight between the friars, the Indians of Tierra Firme, the Crown, and the Spanish colonists. While Queen Isabela (and later Cardinal Cisneros) attempted to slow the Indian slave trade, the Crown by the early 1520s was siding against the religious orders in favor of Spanish slavers and secular officials who had set about legalizing the Indian slave trade along much of the coast of Tierra Firme. The legalization of the trade was the last nail in the coffin for the small missions, effectively ending the indoctrination of much of the indigenous population of present-day Colombia and Venezuela.

The missions provide us with a window into the developing Spanish empire, showing the economic, legal, political, and religious, realities of a society in flux. They also show us the links between the “spiritual conquest” and the economic and/or military conquest of Latin America.Footnote 11 At times the two conquests worked together, and most early modern Iberians (including the Crown and the Pope) would not have separated them, especially given that Spain's earliest claims to the Americas rested on papal bulls. Thus, the Crown actively supported missionary activity in the New World, for example, the missions that are the subject of this article. Nor did Iberians separate spiritual from military conquest: one of the goals of war and pacification was the conversion of the conquered people.Footnote 12 In other words, the Sword was to enable the victory of the Cross.Footnote 13 Economic exploitation was also linked to the Christianization of Americas' native peoples, in the institutions of the encomienda and repartimiento. While the Spanish colonists could extract labor and tribute from their commended Indians, they were also obligated to provide them with protection and religious instruction.Footnote 14 Many abused these systems, but the revenue collected from indigenous labor also served to fuel the continuance of the “spiritual conquest.”

Nevertheless, in the case of Tierra Firme, the two conquests did not facilitate one another. While the friars fought to conquer indigenous souls, they did so without the full support of the rest of the Spanish empire, particularly the local secular rulers and merchants of the Caribbean. The divide between the two groups was both intentional and inadvertent. On the one hand, the taking and purchasing of indigenous slaves on the coast of Tierra Firme benefited many Spanish colonists, and the Crown as well, but gravely harmed the delicate alliance between the friars and their indigenous flocks. However, the friars themselves, in an effort to protect the Indians, made the division even greater by trying to isolate their communities from the larger colonial enterprise. By separating the two conquests, the friars and their missions were left exposed to both slave raids and indigenous attacks.

The division between the friars and the majority of colonists in the Americas, as well as the inherent contradictions of the twin “spiritual” and military conquests, are revealed in the few and fragmentary sources that remain for the missions. Through friars' correspondence, court cases, royal decrees, and colonists' narratives we can witness the dual struggle over tangible power and ideas as these notions crossed the Atlantic during the early years of Spanish colonization. While these documents do paint a partial picture of the growing empire, they do not afford much insight into the indigenous perspective, despite the fact that many of the letters' central themes are the fate of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. Here, we find an important silence, in both the story of the missions and the larger tale of Spanish colonization in the Caribbean.Footnote 15 Even the friars' writings shed little light on the lives of the various Indian tribes they encounter, focusing instead on how many Indians came to church, or their “bellicose” nature.

In most of the documents, the Indians appear as one-dimensional figures that the Spanish act upon, given agency only when they rebel. It is this rebellion that brought the missions and the Indians of Tierra Firme to the attention of Spanish authors. Had Indians not rebelled, we might never have heard even the little of their voice that comes through to us. When we do hear an indigenous voice, it is the voice of an indigenous elite. We have the words—though filtered through Spanish officials—of such caciques as don Alonso, Anaure, and Maraguey, but we do not have the experiences of the women, children, or subject Indians. While these glimpses of the indigenous perspective do give us clues as to why they rebelled or how they viewed the Spanish, we may never uncover the complex economic, social, and political realities of the Indians of Tierra Firme in the early sixteenth century. Nevertheless, the documents still provide historians with important insights into the early years of Spanish colonization.

This was a time when the success of the Spanish was not yet an accomplished fact and had no future assurance. Here we see colonists struggling to find laborers, friars barely surviving on the edges of the empire, the Crown attempting to garner control of his subjects, and Indians actively fighting both slavers and friars—effectively rejecting the Spanish, at least for a time. These fragmentary records then provide us with a rare opportunity to witness the complexity of the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Paradoxically, it may be that this very scarcity of sources has worked to keep the story of the missions of Tierra Firme silenced. It may be that because the Franciscan and Dominican missions of Tierra Firme ended in failure, few historians have examined the experiments in depth, moving on instead to more positive outcomes of the spiritual endeavor. The few scholars who include the missions in their works usually relegate them to a single paragraph or footnote in their much larger histories of Venezuela, or profiles of Bartolomé de Las Casas.Footnote 16 Only one scholar, Lawrence A. Clayton, has followed the friars from Española and Spain to Tierra Firme, in his masterful biography of Bartolomé de Las Casas.Footnote 17 Yet, even Clayton's focus was not on the missions themselves, nor the indigenous people of Tierra Firme, but on Las Casas's actions, beliefs, and manipulations in both Spain and the Caribbean. While Las Casas is no doubt the most famous friar to visit Tierra Firme, many other clergy journeyed there and spent more time in the territory, including the equally influential Pedro de Córdoba and Antonio de Montesinos. Their time in Tierra Firme influenced all these men and their future evangelical endeavors.

First and foremost, the missions provided the Dominican and Franciscan friars with a firsthand look at the many difficulties and obstacles of converting indigenous peoples in the Americas, even those far from Spanish-controlled mines or villages, which might have interests of their own in regard to the Indians. These barriers originated with Indians themselves, as well as fellow Spanish colonists. Tierra Firme, then, served as a kind of testing ground for future (more successful) evangelical efforts in Mexico, Peru, and Florida.Footnote 18

The brief treatment of the missions by historians minimizes their historical significance and removes them from the larger narrative of colonial Latin America. Despite their short duration, they were inextricably linked to many larger conquest patterns and institutions, most clearly to the developing “spiritual conquest.” The royal allowances and support received by the friars demonstrates how committed the Crown was to the conversion of the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas. The religious goals and practices of the friars and royal officials as implemented in Tierra Firme would resonate through the future of missions, schools, and churches across Latin America.

By examining the history of the missions we can also see how power and law operated (or did not) in the burgeoning Spanish Empire. The disparity between the royal provisions and instructions and what actually happened in both Santo Domingo and along the coast of Tierra Firme is striking. Here we see the stirrings of the soon-to-be-common policy of “Obedezco pero no cumplo,” or “I obey but I do not comply.” This statement became common among both conquistadors and colonists who remained loyal to the Crown but refused to comply with a particular order or decree for pragmatic reasons. For many, Spain and the Crown were so far away that obedience to them in the face of practical needs and circumstances in the Americas did not make good sense.Footnote 19 The continuance of the Indian slave trade in Dominican and Franciscan controlled Tierra Firme is a perfect example. Nevertheless, and regardless of distance, King Charles I (later Emperor Charles V) did actively move to consolidate control over the growing colonies from the 1520s forward. And as Crown control solidified, meaningful reform was created, culminating in the New Laws of 1542 that outlawed Indian slavery. However, during the interim the Indian slave trade thrived, crushing the hopes of the Franciscan and Dominican friars in Tierra Firme.

While the “spiritual conquest” was central to the creation of the Spanish Empire, the colonial elite could not afford to place the missions' needs above those of the struggling colonies, especially as conditions deteriorated in Española and Puerto Rico near the end of the third decade of colonization. As death and disease stalked the native inhabitants of the Caribbean, the need for Indian slaves could not be ignored, even by religious leaders like the Jeronymites. Thus, while evangelization continued at the core of the empire, the frontier missions and indigenous populations were often sacrificed. Ultimately, the missions serve as an example of the fate of larger Latin America. At the edges of the Spanish empire, economic and political goals would often win over spiritual ones. Similar episodes would be repeated in Spanish colonies like Florida, Chile, and Río de la Plata.

Nor were the Spanish the only Europeans to missionize to the indigenous peoples of the New World. The French, Dutch, Portuguese, and the English all endeavored to convert Indians to Christianity and built missions of varying success. An important distinction between the Spanish “spiritual conquest” and that of other European powers is that only the Spanish missions received Crown sponsorship. In contrast, efforts to missionize Indians in French, Dutch, English, and Portuguese colonies were supported only by the Pope and had to act independently of the larger state, adding another layer of difficulty to their work.Footnote 20 Nevertheless, the various missions did share some elements, with a few even meeting fates similar to that of the missions of Tierra Firme. For example, in the Portuguese colony of Brazil we find Jesuit, Franciscan, and Calvinist missions during the 1550s and 1560s. While the various priests were hopeful regarding the Tupinamba's capacity for conversion, despite their demonstrated practices of vengeance and ritual cannibalism, the missions faced challenges presented by secular Portuguese colonists, particularly slave raiders.Footnote 21 Jesuits in New France in the first half of the seventeenth century met like obstacles in their missions, as both secular colonists and the diverse indigenous groups depended upon slavery for economic and social gain.Footnote 22 Even the English colonists of New England, who were the most adamant about maintaining their distance from Americas' indigenous peoples for fear of losing their own Christian and English identity, had embarked on missionizing efforts by the second half of the seventeenth century. The Puritan missions were known as praying towns, where Indians were taught to read and write as well as steeped in the Protestant faith. While these missions did enjoy some success— by 1670 there were at least 14 praying towns in the colony of Massachusetts—they ultimately succumbed to the stresses of disease, war, and the Indian slave trade. In fact, many Christian Indians were enslaved and shipped to the English Caribbean in the wake of King Philips' War in 1676.Footnote 23

While these diverse experiences across the Americas and across European empires provide us with insight into the spiritual and military conquests of the New World, those of Tierra Firme, home of the first missions, demonstrate the birth of these patterns and policies. Additionally, they highlight how the Indian slave trade impeded the earliest efforts of the “spiritual conquest.” By the 1520s, the friars were forced to admit defeat. Soon after, the area became a grangería de indios, an enterprise providing Indian slaves for the more profitable areas of the Empire.Footnote 24

How the Missions Came to Tierra Firme

One might well ask why the Dominicans and Franciscans were so intent on forming religious communities along the coast of Tierra Firme, an area at the very edge of the Spanish empire. The answer reveals much about the progress of both secular and religious conquests in the Americas during the first three decades of colonization. By 1513, Spanish explorers and settlers had wreaked havoc on the Taínos of Española through warfare, enslavement, and the encomienda system.Footnote 25 As early as 1511, Dominican friars, recently arrived under the leadership of Pedro de Córdoba, began calling for reform after witnessing the plight of the Taínos of Española. In a fiery sermon on the morning of December 21, 1511, friar Antonio de Montesinos condemned the actions and behavior of the Spanish colonists, going so far as to question their right to enslave and wage war on the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Following the sermon at the nascent cathedral of Santo Domingo, controversy enveloped the colony and incited a debate on the humanity of America's indigenous peoples that continued for nearly half a century.Footnote 26 Among the many issues addressed by Montesinos's sermon was the recent dramatic increase and expansion of the Indian slave trade. He also emphasized the right of the Taínos to be converted on the grounds of their humanity and accused the encomenderos of preventing conversion by overworking them.Footnote 27 Debates erupted after the sermon, throughout the Indies and in the Spanish court. Dominicans, Franciscans, and encomenderos were all present at these deliberations, which took place in Burgos from 1512 to 1513.Footnote 28 Though Montesinos journeyed to Spain to argue for the salvation and freedom of the Indians, his case and arguments were largely ignored. Instead, the Crown sided with the more moderate Franciscans who sought amelioration for the Taínos within the existing Spanish structures on the island, including the encomienda system.

On December 27, 1512, King Ferdinand promulgated the Laws of Burgos, the first concerted legal effort to address the relationship between Spanish colonists and the native peoples of the New World. To limit the suffering of the Indians, the Laws of Burgos attempted to improve the working conditions in the mines, limit the number of Indians any encomendero could possess, and ensure that Indians received sufficient food, clothing, and religious instruction.Footnote 29 Nevertheless, the laws also validated the institution of the encomienda and the legality of the Crown's exploitation of the native peoples of the Americas. In fact, along with the laws attempting to help the natives of Española, there was simultaneous confirmation of the status of foreign Indian slaves. Although naborías (similar to indentured servants) and Taínos of the Greater Antilles had to be indoctrinated in Christianity and treated with “love and gentleness,” any Indian declared a slave could be “treated by their owner as he pleases.”Footnote 30

It follows then that the Laws of Burgos, although they were the first step in reforming Indian policy, were riddled with inconsistencies and limitations, and ultimately did little to change the situation of America's indigenous peoples. This was especially true at the edges of the empire. Thus, the Dominicans, and many Franciscans, harshly criticized the law code. It was also at this point that the Dominicans, and a group of Franciscans, turned their attention to helping and converting indigenous peoples who lived far from the centers of Spanish settlements. They believed that conversion to the Catholic faith was nearly impossible within the encomienda system. As they searched for a territory suitable for the creation of the first religious communities, their gaze turned to the coast of Tierra Firme, more specifically present-day Venezuela.

Located on the edge of the burgeoning Spanish empire, the coast of Tierra Firme with its large indigenous populations remained largely untouched by Europeans in 1513. The Dominican friars, again led by Pedro de Córdoba, viewed the region and inhabitants as the perfect place to begin Catholic missions, far from exploitative Spanish colonists. Perhaps to quiet the friars, or due to genuine interest in the project, King Ferdinand issued Córdoba a royal license to settle and control a vast expanse of Tierra Firme. Here the Dominicans, soon followed by groups of Franciscan friars, were to establish small settlements to educate and indoctrinate the local Indians in the Catholic faith.Footnote 31 Córdoba and his cohorts firmly believed that they would be able to colonize territories using only peaceful methods, so long as those colonies were isolated from other Spanish settlers. According to the friars, regular settlers molested, abused, and scandalized America's indigenous peoples. Further, Indians' rebellion and refusal to adopt the Catholic faith could be directly blamed on the indignities they suffered. Thus, the influence of the larger Spanish population had to be controlled if not altogether prevented. As of 1513, the coast of Tierra Firme remained relatively isolated from the growing Spanish empire, and its “scandalizing” settlers.Footnote 32 Here, the friars hoped, their efforts would not be undermined by secular Spanish colonists and officials.

But, as we saw with the experience of don Alonso, and will see in other examples, all the friars' efforts and plans would be in vain. Many factors contributed to the failure of the missions of Tierra Firme, but the largest obstacle standing in the friars' way was greed.Footnote 33 The secular leaders, officials, and residents of the colonies fought with all their might to maintain their rights and privileges to extract labor and tribute from both the Caribbean land and its peoples. Of utmost importance during this period was the increasingly profitable circum-Caribbean Indian slave trade.Footnote 34 Many viewed Tierra Firme as one of the best sources for this trade.

The First Religious Mission in the New World, 1513–1515

In planning the settlements, Pedro de Córdoba sought to ensure the isolation of indigenous missions from larger Spanish colonies and industries, which relied on Indian labor and exploitation. This vision can be seen in the asiento (grant) he negotiated with the Crown for the missions in Tierra Firme. To preclude other Spaniards' interests from contaminating the relationship between Venezuela's indigenous peoples and the friars, Córdoba's royal license forbade secular Spanish colonists from settling in the province of Paria.Footnote 35 In fact, no other Spaniards could legally conduct business or trade in the territory without permission and license from the Dominicans or their designated representative. The royal order even prohibited any unauthorized communication between the Indians of Tierra Firme and Spanish colonists.Footnote 36 Any Spaniard caught disobeying the order and mistreating an Indian, intentionally or unintentionally, would face confiscation of one-half of their possessions by the Crown.Footnote 37 Interestingly, the Crown would keep only half the confiscated revenue, distributing the rest to deserving colonists of Española. This clause may have served to encourage colonists to report one another's illegal activities. In this way, the king ensured that the royal agenda would be served, whether by colonists' obedience or defiance of the law. Either the friars would succeed in saving the souls of Tierra Firme's Indians and make the territory profitable at the same time, or he would be able to collect monies and goods from defiant colonists.

But the Crown did much more than issue Córdoba and his fellow friars control over much of Tierra Firme's coastline. The king also tried to ensure the settlement's success, or at least its survival, by providing the missionaries with necessary supplies. The Crown promised to pay for the passage of up to 15 friars and to secure all provisions they would need, including mats and blankets, for their journey to Española.Footnote 38 As theirs was chiefly a religious endeavor, the priests and friars were also supplied with a variety of sacred objects, including a very large crucifix, a copper cross, two silver chalices, several copies of the Bible, a religious calendar, images of several saints, and 30 grammar books.Footnote 39 The inclusion of grammar books shows that friars not only intended to practice their Catholic faith among the Indians of Tierra Firme, but likely planned on teaching them both the sacraments and the Spanish language. In this way the missions would be similar to the newly established school for hijos de caciques in Española's nascent settlement of Verapaz.Footnote 40

Once the friars arrived in the Caribbean, the governor of Española, Diego Colón, was to provide them with all the provisions and supplies they needed for the settlement itself. This included ships, food, and even four or five Indian guides. Here we see evidence of the Indian slave trade that already existed between Tierra Firme and the Greater Antilles. In his orders to Colón, King Ferdinand specified that the residents of Española were to locate some of the Indians brought from Tierra Firme who could serve as guides and translators for Córdoba's mission. King Ferdinand further instructed that if the Indians in question were slaves, which was more than likely, that Miguel de Pasamonte (the treasurer of the island) should purchase the slaves from their owners and confiscate their bills of sale.Footnote 41 These slaves, now belonging to the king, would then accompany the friars.

Beyond providing a window into the slave trade, the royal order also underscores the importance of Indian intermediaries, or go-betweens, for Spanish missions of exploration and colonization.Footnote 42 Governor Colón was also to supply the friars with large quantities of wine and flour within a few months of their journey to Tierra Firme. In fact, the residents of Española were to check up on and continue to provision the friars every three to four months.Footnote 43 In theory then, the friars had all they needed to create and maintain a successful settlement: supplies, indigenous allies, and Crown support. However, as in other matters, the king had little power to enforce his orders and decrees once they were delivered to the Indies. Nor, as we shall see, would Ferdinand fight for the Dominican missions or indigenous reform when faced with other obstacles and demands in the growing empire.Footnote 44

Having gathered their supplies, instructions, and licenses, three priests set sail for the Caribbean in late summer of 1513. The chosen men were the friars Antonio de Montesinos, Francisco de Córdoba, and Juan Garcés.Footnote 45 In Española, Pedro de Córdoba met the men and gave them additional supplies for the settlement, including the Indian guides that were to be their slaves.Footnote 46 After some time in Española, the friars moved on to Puerto Rico, where Montesinos fell gravely ill. He did not finish the journey, but stayed behind. He planned to join Garcés and Córdoba within six months, when additional provisions were to be sent to the mission.Footnote 47

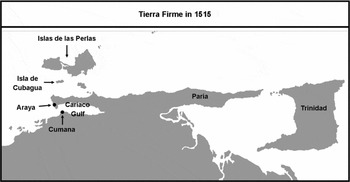

In late 1514, Garcés and Córdoba arrived in the province of Paria, 200 leagues from Puerto Rico. According to such chroniclers as Bartolomé de Las Casas and Antonio de Herrera, the friars received a warm reception from the local Indians. After a few days of hospitality, the pilots who had escorted the friars to Tierra Firme returned to Puerto Rico, leaving the two men alone to begin their mission. It was to be called Santa Fe en Píritu, near to Araya and Cumaná.Footnote 48 For the mission's location, see Figure 1.

Figure 1 Tierra Firme in 1515

Unfortunately for the friars, the amicable relationship between the clergy and Indians was not destined to last. Whether it endured only a few days, or some months, is unknown, but it is clear that their alliance had faltered by early 1515. If there was discord between the Indians and the friars over issues of conversion, we have no documentation of this type of conflict. Nonetheless, it appears that tensions rapidly escalated (or were instigated) by the Spanish merchants who continued to violate the Crown's orders prohibiting them from conducting business along the coast of Tierra Firme. The worst offenders of these ordinances were the Spanish slavers.

Regardless of the royal instructions or allowances given to the friars, Tierra Firme was becoming incorporated more and more into the larger Spanish orbit. Not only did the coast of Tierra Firme provide the Spaniards with pearls, but by 1515, the salt mines of Araya were fueling the movement of settlers to the region.Footnote 49 Still, the region's premiere resource during much of the second decade of the sixteenth century remained indigenous slaves. Flotillas and squadrons constantly attacked the coastline and its nearby islands, capturing and enslaving all the Carib Indians they could find. It was on one of these expeditions that the aforementioned Spanish scribe Gomez de Ribera captured don Alonso and his family from Cumaná.

Despite the friars' pleas for the return of Alonso, and the support that they received in Santo Domingo from both Córdoba and Montesinos who denounced Ribera publicly, their requests for the immediate return of Alonso and his family were ignored by the secular officials of the island in 1515. Whether it was too difficult to locate Alonso and his people after their sale, or if it simply was not considered worth the trouble by Española's colonists, they were never returned to Tierra Firme, and their fate remains a mystery.Footnote 50 However, the Crown pursued the issue for some time: as late as January 1518, the newly anointed King Charles I ordered Judge Alonso de Zuazo of the royal Audiencia of the Indies to find the merchant responsible for the illegal capture of Alonso and his family. Of paramount importance to Charles was the location of Alonso's wife, the cacica. Why the Crown was more concerned with the return of Alonso's wife is unclear, unless they already had knowledge of Alonso's death. In any case, the order stated that the cacica and any other surviving relations of Alonso were to be found and immediately returned to the coast of Tierra Firme. The Spanish sailor guilty of the crime would then be forced to pay for all the costs incurred during the Indians' return.Footnote 51 Here we see evidence of Charles's early support of Las Casas and reform, which would increase over time.Footnote 52 However, despite the Crown's orders, there is no evidence that any of the Indians in question ever returned to their homeland. Meanwhile, left unprotected, and without the promised support from the government and colonists of the larger Caribbean, the friars were at the mercy of the Indians of Tierra Firme. Ultimately, the friars and mission paid the price for Ribera's capture of Alonso and his family.

Cisneros's Intervention: A Second Chance for the Missions, 1517–1519

Despite the violent end of the Dominican missions, the religious orders did not give up on their project. In fact, the new leader of Spain, Cardinal Cisneros, was even more committed to a Dominican/Franciscan presence in Tierra Firme.Footnote 53 Like Pedro de Córdoba, he believed that separation from secular Spanish subjects would be the key to the missions' success. In his royal order of September 1516 Cisneros prohibited any Spaniard, except for the friars, from trading or engaging in rescate, along the entire coast of Venezuela, from Cariaco to Coquibacoa.Footnote 54 In the place of Spanish merchants, the Dominican missionaries, or more specifically their representative, would conduct and supervise all trade and rescate throughout the zone.Footnote 55 Any Spaniard found disobeying this law faced confiscation of all goods in their possession at the time.Footnote 56 In theory, these regulations would end all slave raiding or purchasing of indigenous slaves along the coast of Tierra Firme, the practice that Córdoba blamed for the failure of the first mission.Footnote 57 In practice, they would be much harder to enforce.

This is especially true when one considers Cisneros's choice to enforce the legislation: a group of Jeronymite friars.Footnote 58 In addition to the rehabilitation of the missions, three Jeronymites were tasked with investigating and then reforming the entire government of the Indies. Their long-range goals were the salvation of the land's native peoples and the resurrection of Española's failing economy. To achieve them, the Jeronymites planned to gradually replace the faltering, labor-intensive gold-mining industry with sugar production. They also sought to substitute the Taíno labor force with African slaves and to end the Indian slave trade.

With the support of both Cisneros and the Jeronymites, another group of Dominican friars embarked for the coast of Tierra Firme in late 1516 to establish the mission Santa Fe in Chichiriviche. This time, both Pedro de Córdoba and Antonio de Montesinos accompanied the group.Footnote 59 As before, the officials of Española were to provide the friars with all necessary supplies, including Indian guides. Also, the friars were to continue to receive all their provisions from Española to ensure that they would not become a burden to the Indians of Tierra Firme. Additionally, Cisneros charged the Jeronymites with securing all of the coastline inhabited by the missionaries from both Spanish colonists and Carib Indians.Footnote 60 How exactly the Spanish colonists and their soldiers were to patrol the territory, which expanded over 1,000 kilometers, without interacting with any Indians unless authorized by the friars, was not specified.Footnote 61 Figure 2 shows the coastline given to the friars in 1516, in relation to the indigenous provinces where the missions were to be built.

Figure 2 Friars' Territory, 1516

This time, Córdoba's group of friars was not the only one to try their hand at building a mission in Tierra Firme with the help of Cisneros and the Jeronymite reforms. Following Córdoba's example, a party of 14 Franciscan friars received orders to create a settlement in Cumaná in November of 1516, only two months after Córdoba received his instructions and concessions.Footnote 62 They built their mission at the mouth of the river Manzanares, just outside of Cumaná.Footnote 63 Put together, these small missions, populated by a handful of friars, were to lead the conversion, indoctrination, and civil colonization of the indigenous peoples of Tierra Firme and the Pearl Islands.

Upon arriving in Española in January of 1517, the Jeronymites began working to reform the relationship between the Spaniards and the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. First, they interviewed the 14 most powerful colonial officials and encomenderos on the island, men who had every reason to contradict Las Casas and the other friars' tales of indigenous abuse. As one might expect, their descriptions of the Indians were not positive, with most characterizing the Indians as “lazy,” “enemies of work,” “liars,” “drunkards,” and “inclined only to vices, not virtue,” arguing further that the Indians did not possess the capacity to govern themselves in a civilized manner.Footnote 64 In spite of such objections, the Jeronymites immediately prohibited the continuation of the Indian slave trade along the coast of Tierra of Firme and removed all Indians from encomiendas whose owners were absent, basically fulfilling the Laws of Burgos.Footnote 65

Briefly, it looked as if the reformers would succeed. With the power invested in the friars, and an end to the legal slave trade in Tierra Firme, the missions seemed to have a much better chance of success in 1517. However, two problems soon presented themselves. First was the basic inability of the small groups of friars to effect their trade monopoly: hundreds of other Spanish merchants sought to engage in both rescate and other, less invasive exchanges, just as they had before. Second, and perhaps more unexpectedly, many indigenous groups of Tierra Firme were dissatisfied with the arrangement. Not only were they forbidden to trade with multiple Spaniards, taking advantage of competition to gain the best product or price, but also they could no longer legally sell Indian slaves themselves. Indigenous slavery pre-dated the Spanish in Tierra Firme, and slavery was a common outcome of Arawak warfare.Footnote 66 In fact, many wars were fought for the purpose of gathering slaves, perhaps even to exact vengeance on a community that had enslaved members of one's own. The slaves could be exchanged for other goods, used as laborers, or be adopted into the society.Footnote 67 Thus, while indigenous groups did not want their own people to be enslaved, as happened to don Alonso, they had no problem with the institution itself nor with the profit they received from selling “Caribs” to Spanish merchants.Footnote 68 Neither the Indians of Tierra Firme nor the Spanish slavers wanted the slave trade to end, leaving the few missionaries fighting an uphill battle.

Within months after their return to Tierra Firme, the friars began to complain about new slaving expeditions to nearby Trinidad and even into Paria, territory nominally controlled by the religious orders. Córdoba even reported slaving raids entering into Chichiriviche, the province recently settled by the Dominican friars.Footnote 69 By early 1518 the territories under assault by slave traders included the valley of Chichiriviche, the provinces of Cumaná, Paria, Cariaco, and Maracapana, and the areas that formed part of Castilla del Oro (present-day Colombia).Footnote 70 Virtually the entire region governed by the friars was being frequented by slavers. Whether the merchants obtained their slaves through peaceful or violent methods, the removal of indigenous peoples from Tierra Firme left the region generally unsettled, as the demand for Indian captives provoked increasing conflict between indigenous groups. Because the majority of the slaving expeditions were at least nominally illegal, it is difficult to be sure of the number of raids, how the slaves were obtained, or how many Indians were taken to Santo Domingo and San Juan. We do know that at the very least the slaving was substantial enough to seriously preoccupy the friars throughout 1517 and into 1518.

Smallpox, Defining Carib Lands, and the Consequent Growth of the Slave Trade

In early 1518, disaster of another kind struck. Just as the Jeronymites were attempting to reform the relationships between Spaniards and Indians across the Caribbean, and as the friars began to make headway in Tierra Firme, Española faced the first outbreak of smallpox in the New World. According to officials on the island, the illness devastated the remaining indigenous population, killing up to one-quarter of the Indians in Española in a few months.Footnote 71 The huge loss of population caused the Jeronymites to turn their attention to finding new sources of laborers for the island. Ideally, this would not be foreign Indians. From the beginning the Jeronymites had promoted the use of African slave labor over indigenous, as evidenced by their outlawing of the Indian slave trade upon their arrival in the Caribbean. In early 1518, they issued a decree that allowed for the purchase and transportation of Bozal African slaves to the island of Española.Footnote 72 However, they quickly realized that the drastic labor shortage on Española would not be solved by the arrival of a few thousand African slaves—that it would be necessary to import both Africans and Indians.Footnote 73

Thus it was that only a year after the Jeronymites made the Indian slave trade illegal they officially lifted the prohibition on trading for slaves in the Pearl Islands and along the coastline of Tierra Firme.Footnote 74 They then went a step further by granting licenses for Spaniards to take or trade in any Indian slaves throughout Tierra Firme that were already held as slaves by the local Indians.Footnote 75 The Jeronymites also revitalized the war on Carib Indians and in addition labeled the majority of Indians living on the coasts of Tierra Firme as Caribs, thereby opening the territory to legal slave raids. Many of the slaving licenses issued by the Jeronymite government included permission to capture Caribs and to engage in rescate for Indian slaves. For example, Treasurer Miguel de Pasamonte received a license allowing him to go to Tierra Firme to enslave any Caribs he might find to labor in his expanding sugar mill.Footnote 76 The Jeronymites even sponsored at least one slaving caravel under the command of Diego de Caballero, which returned to Santo Domingo with between 150 and 200 Indians from Paria.Footnote 77 It appears that when the survival of the Spanish enterprise in the Caribbean was in question, the Jeronymites could quickly refocus on secular and economic concerns, pushing the “spiritual conquest” to the side.Footnote 78

Slaving expeditions from June to October of 1519 captured and registered over 500 Indian slaves in Santo Domingo. Over half of these Indians were women.Footnote 79 The Jeronymites also issued licenses for the residents of Española to purchase Indian slaves, specifically Caribs from the coast of Brazil, from Portuguese traders.Footnote 80 In or before 1520, Rodrigo de Figueroa, a judge of the royal court in Santo Domingo, reported to the king that the majority of ships docking in Santo Domingo carried only Carib slaves from Tierra Firme.Footnote 81 In two months alone, 600 Indian slaves were sold publicly in Santo Domingo for 13 pesos each.Footnote 82 The judge Alonso Zuazo confirmed Figueroa's observations, claiming that up to 15,000 Indians from the Lesser Antilles and the coast of Tierra Firme had been captured and enslaved in 1518 alone.Footnote 83 To distinguish these slaves easily from the naborías or from the few free Indians, they were branded with a large “C” for Carib on their upper arms.Footnote 84

This unrestricted slaving of Carib Indians caused many to question whether or not those labeled as Caribs were truly cannibals or even enemies of the Spanish. One of the loudest opponents was none other than Bartolomé de Las Casas, who began petitioning the new King Charles I (he took the crown upon Cisneros's death in late 1517) immediately upon his arrival in the Spanish court.Footnote 85 Charles I responded in 1520 by ordering Rodrigo de Figueroa, the newly appointed Justice of Española, to conduct an ethnographic inquiry into the inhabitants of the Caribbean. Figueroa was to determine exactly which territories were inhabited by Caribs and in which lived peaceful Indians allied with the Spanish (for example those close to the friars), otherwise known as aruacas or guatiaos.Footnote 86

In his official report to the Crown, Figueroa made the purpose of his project clear: he was to “indicate in which territories Carib Indians live and as such can and should be taken as slaves by the Christians.”Footnote 87 His report was based solely on interviews with “pilots, captains, and sailors, and other persons who are accustomed to travel to the islands and coast of Tierra Firme.”Footnote 88 Essentially, Figueroa's sources were slavers or traders who themselves would benefit from the expansion of the legal definition of Carib lands, but not from the reduction. Figueroa's investigations also coincided with a new low in the labor supply of Española, following the smallpox epidemic but before the African slave trade had reached a critical mass. With the loss of the indigenous population, many Spanish colonists began seeking opportunities in other islands or the mainland, leaving many towns abandoned.Footnote 89 The Crown would have thus experienced a drop in revenue, due both to a lower production of Española's crown-owned gold mines and to the fact that fewer colonists had any taxable profit.

In this context, Figueroa's wide designation of Carib lands makes sense and may have been what the Crown intended. Figueroa declared that all islands in the Caribbean not inhabited by Christians, other than Trinidad, Barbuda, the Lucayos, Los Gigantes, and Margarita, were Carib lands.Footnote 90 In addition to those islands, much of the coast and interior of Tierra Firme were defined as Carib. These were some of the most densely populated regions, most of which had yet to be fully explored. Slaving licenses to these areas could have served a double purpose then: to supply labor to the Greater Antilles and to instigate and fund new exploratory ventures. From all of these lands, licensed Christians could legally “enter and take, seize and capture, and make war and hold and possess and trade as slaves those Indians who in the designated islands, lands, and provinces are judged as caribes, being permitted to do so in whatever manner, so long as they are first given permission by the justices and officials of your Majesty.”Footnote 91 While the Indians living in the lands surrounding the Dominican and Franciscan missions were designated as friendly, or guatiaos, the proximity of the missions to Carib lands made it difficult to distinguish between the areas where one could enslave Indians and where one could not.

After the publication of Figueroa's report, the number of slaving licenses, already on the rise after the Jeronymite's change in legislation in 1518, grew rapidly. By August 1520, Lucás Vázquez de Ayllón, Juan Ortiz de Matienzo, Marcelo de Villalobos, Rodrigo de Bastidas, García Hernández, Miguel de Pasamonte, and Diego Caballero had all received licenses to conduct both rescate and slave raiding in Carib territories.Footnote 92 In addition to issuing licenses to individuals, the Crown provided some colonists with much broader slaving authorizations. Juan de Cardenás, a resident of Sevilla, received one such license in August of 1520: it allowed him to prepare and arm two caravels in Santo Domingo. The ships were to travel to Barbados, Isla Verde, Trinidad, and the province of Paria to conduct rescate for gold, pearls, precious stones, and Carib slaves. These slaves were to be branded as Caribs and sold in the markets of Santo Domingo.Footnote 93 The Crown would receive taxes on all the slave sales.

Indigenous Rebellion and the End of the Missions of Tierra Firme

By 1520, the Indians of the coastal region of Tierra Firme that lay near the province of Chichirivichi were in rebellion against the numerous slave raids. The Spaniards then designated all Indians who took part in the uprising as Caribs, though those so named adamantly denied the charges of cannibalism.Footnote 94 The indigenous resistance only solidified the Spanish legal and political designations, as any Indian who opposed the Spanish was labeled as a Carib and could legally be captured and enslaved.Footnote 95 According to both the Franciscans and Dominicans, the constant presence and threat of Spanish slaving flotillas prevented, or at least limited, the number of Indians who joined the Spanish missions. For example, by 1519 the seven Franciscan friars living on the coast of Cumaná had attracted only 40 Indian followers, many of them indigenous children. The fact that there were so many children may mean that parents were using the missions as a type of protection for their offspring. Fray Juan Vicente worried about the very survival of the missions. He complained that the officials of Española were slow to send supplies, even the most basic, like cazabe (bread made from the roots of the manioc plant). Additionally, he worried that few new friars were coming to Tierra Firme, further stunting the growth of the missions.Footnote 96

However, the most pressing issue for Vicente was the slave raids that were steadily increasing tension between the friars and the coastal indigenous groups.Footnote 97 This loss of nearby indigenous allies, who had earlier fought against the Caribs of interior South America, isolated the largely defenseless religious communities from their attacks. By 1520, even fray Pedro de Córdoba confessed to the difficulty of getting the Indians of Tierra Firme to church regularly, let alone convincing them to renounce their own religious beliefs and cemíes.Footnote 98 Córdoba himself left the coast in 1520, perhaps due to his disillusionment.Footnote 99 Other friars complained of the Indians' belligerent nature.Footnote 100

Despite the friars' pleas to end all legal slaving in the region, officials ordered that the Spanish armadas and expeditions focus on enslaving only Caribs. For an example, we can look to Juan de Ampiés, the royal factor.Footnote 101 Ampiés issued a proclamation prohibiting slavers from assaulting the peaceful indigenous groups who resided along the coast 40 leagues east of the Gulf of Venezuela.Footnote 102 Indians living outside this region, or caught there, could be legally enslaved. These prohibitions were not only ambiguous but nearly impossible to enforce: because officials relied on the slavers themselves to account for where they encountered and captured their Indian slaves, slaving continued. Things only worsened in 1521 when Anaure, an important local cacique, Christian, and ally of the friars was captured during a slave raid. His daughter also fell victim to the raid. This time the mistake was recognized immediately by the factor Juan de Ampiés in Santo Domingo. Anaure was the leader of a power and populous territory close by the Spanish town of Coro. Apparently Ampiés had dealt with Anaure personally in the past and considered him a loyal ally.Footnote 103

As in the case of don Alonso, a Spanish captain, Gonzalo de Sevilla, took advantage of the friendly relationship between Anaure and the local Spanish population (especially the friars). Gonzalo engaged Anaure, along with several other caciques, in conversation while a group of armed, hidden Spaniards snuck up on the group and captured half of them in a violent assault. These Indians they loaded on board their ships and then sailed to Española. Upon their arrival in Santo Domingo, Anaure was able to appeal his case to Ampiés, who immediately began working toward the return of the cacique and his daughter.Footnote 104 During his stay with Ampiés, the cacique told him of the almost constant slave raids that assaulted the coastline of Tierra Firme, disregarding which Indian groups were at peace with the Spanish and which were actual Caribs.Footnote 105

Even soldiers ostensibly sent to help and protect the friars, including a group sent by Bartolomé de Las Casas to reinforce the Franciscans near Cumaná in July of 1520, deserted the missions.Footnote 106 Earlier, Las Casas had received an enormous grant of 270 leagues on the peninsula.Footnote 107 Nonetheless, the soldiers invaded this area to conduct slave raids of their own along the coast.Footnote 108 Others, from both Española and Puerto Rico, focused their slaving expeditions in Maracapana, only five leagues distance from the Dominican missions.Footnote 109 The friars were losing any control they may have had in Tierra Firme, something Las Casas had to admit. In an effort to limit the impact of the slavers, Las Casas tried to make a compromise with the colonists of the Caribbean, even agreeing to allow the enslavement of Indians in the interior in exchange for monetary support from Santo Domingo and a promise of no coastal raiding.Footnote 110 Here again, we see the tension between the secular and spiritual conquests, as well as the two faces of Las Casas: entrepreneur (pragmatist) and reformer.

By late 1520 it seems that the constant slave raids had taken their toll—the friars' concerns were correct. On September 3, 1520, cacique Maraguey entered the Dominican monastery during a mass. Maraguey was a neighbor of the mission and had friendly relations with the friars. On this day though, Maraguey brought with him many Indians from his own territory and a nearby one called Tagares. Once inside the church, they killed two friars in addition to nine others who were residing in the monastery, including one Indian serving as a translator for the friars.Footnote 111 Next, the Indians robbed the monastery, stealing all the religious ornaments, valued at up to 1,000 pesos. Finally they burned down the monastery buildings and killed the friars' horse, dog, and cow. Only one Indian survived the attack, a servant of the friars from the coast of Tierra Firme. The survivor travelled to Cubagua, where he reported the attack to Antonio Flores, the governor of the island.Footnote 112

Simultaneous with the assault on the monastery were several other attacks against secular Spanish traders throughout the region, from Maracapana to Cuanta and Cumaná.Footnote 113 Finally, in early 1521, the Indians of Tierra Firme attacked the Franciscan monastery of Cumaná. The Indians killed two friars, along with five or six Indian servants taken from Española; here again, they attacked while the friars were celebrating mass.Footnote 114 Why the Indians chose to assault both monasteries during mass is uncertain, but it is possible that they wanted the attack to be a clear, public statement against the Spanish friars. Why they killed the indigenous servants at Cumaná, when they had let others go in the past, is also unknown. Perhaps they targeted the Indian servants because they were foreign Indians, or because they had converted to Christianity. In any case, after murdering the friars and servants, the attackers robbed the church, stealing all the religious ornaments including the friars' robes and chalices. They then burned down the friars' huts (bohios) and the storehouse with all of the mission's supplies and weaponry.Footnote 115 Finally, they broke the church bell, and killed the friars' horses and one mule.Footnote 116 It seems the Indians were rejecting all links to the Spanish, even the livestock that could have been of use.

Whether these attacks were orchestrated or isolated incidents is uncertain, but their similarities are striking. So are the Spanish responses to them. When Spanish officials received word of the series of rebellions, beginning with the assault on the monastery near Maracapana, the governor of Cubagua gathered five ships with 40 men to journey to Santa Fe to punish the Indians.Footnote 117 Then, in January 1521, the royal court of Santo Domingo organized a much larger expedition, led by Captain Gonzalo de Ocampo, to attack and declare war on the Indians of Cumaná, Santa Fe, Tagares, and Maracapana.Footnote 118 Ocampo was specifically ordered to locate and capture the cacique Maraguey and his brother, to make an example out of them. The avengers were allowed to do much more than arrest those guilty of attacking the friars and other Spaniards: Ocampo and his men were also permitted to make war on and enslave any Indian who resisted their advance. However, any Indian who helped the Spaniards to located Maraguey or others implicated in the deaths of the friars was to be forgiven and pardoned. This strategy, it was hoped, would make peace in the region while also providing indigenous slaves for the Greater Antilles.Footnote 119

It was at this moment that Bartolomé de las Casas finally arrived in the Indies, prepared to journey to Tierra Firme and establish more settlements. Upon hearing of the rebellions and Ocampo's expedition of vengeance, he was appalled. The priest even tried to stop Ocampo, who refused to recognize Las Casas's control over the entire region.Footnote 120 Instead, Ocampo sailed to Maracapana where he and his crew attacked and enslaved Indians all along the coastline. The fate of Maraguey and the other rebellious caciques is unclear. However, within two months of Ocampo's expedition at least 600 Indian slaves from Tierra Firme were sold in Santo Domingo.Footnote 121 Presumably at least some of the culpable Indians were among the captives.

Conclusion

As one can imagine, the reprisal on the Indians of Tierra Firme only served to ruin whatever goodwill might have remained between the surviving friars and the indigenous groups of present-day Venezuela. Whatever Ocampo may have accomplished in 1521–22, the Dominican and Franciscan missions did not return to Tierra Firme.Footnote 122 Instead the Crown took control of the region, parceling out governorships to secular officials in Spain and the Indies. It was at this point that the pearl fisheries of Cubagua and Margarita began to produce larger quantities of pearls; now the Indians of the coast were needed as slaves in both the Greater Antilles and the Pearl Islands. Slaving expeditions and raids increased throughout the 1520s, and in response more Indians responded violently. Again, more indigenous groups were labeled as Caribs. And the cycle repeated itself, year after year.

In fact, slavers of the Caribbean continued to use the destruction of the missions as rationale to enslave the Indians of Tierra Firme for some time. As late as 1528, letters to the Crown detailed the massacres and used them as evidence to support the enslavement of the Caribs of Tierra Firme and Castillo del Oro.Footnote 123 As the need for labor throughout the Caribbean grew, in both the pearl fisheries and the increasingly productive sugar mills of Española, the Crown began issuing more licenses to engage in trade and rescate along the coast of Tierra Firme. By 1528, the number of licenses had increased so greatly that hundreds of slaving squadrons assaulted the coast of Tierra Firme, many under the guise of legal trading fleets.Footnote 124 The licenses of rescate essentially facilitated the legal and illegal enslavement of hundreds of Indians along the coast of Tierra Firme. Also in 1528, the Crown declared a royal monopoly on the pearl trade, making the need for laborers in the pearl fisheries of utmost importance to the royal purse. The Crown then had even more incentive to ignore the illegal slave trade.Footnote 125

In these massive expeditions of rescate during 1526–28 we see the origins of the grangerías de indios. From these so-called ranches, which comprised much of Tierra Firme, Spaniards would gather and harvest thousands of Indian slaves for the next decade. These massive operations, augmented by smaller expeditions, would bring the indigenous slave trade to its climax and devastate many of the native populations of present-day Venezuela and Columbia. Ultimately, the drive to find and supply Indian slaves would create its own enterprise, with Spaniards living solely from the capture and sale of Indian slaves. In fact, the indigenous slave trade was already considered by 1528 to be the second-best way to profit from Tierra Firme, just behind the pearl fisheries.Footnote 126

In a little over a decade, the Spanish vision of the Indians of Tierra Firme had been transformed. In 1513, Tierra Firme had appeared to be an untouched region, with thousands of peaceful Indians ready to convert to Catholicism, if only they could be spared from the negative influence of secular colonists. Whether this dream could have been realized will never be known, as the friars were never able to keep the Indians of Paria or Cumaná or Maracapana isolated from the larger and steadily expanding Spanish Empire. As the missions grew, so did the trading and slaving expeditions. And after the discovery of the pearl fisheries, which attracted hundreds and then thousands of Spanish colonists, the hope to keep Tierra Firme separate from the rest of the Caribbean was permanently lost. While indigenous rebellions did not initially cause the friars to lose confidence in their missions, they did lead to further legalization of indigenous enslavement. With more slaving came more disruption of indigenous communities, leading to more indigenous unrest and revolt. In the end, the missions could not survive the constant slave raids and the violence they entailed. In the failure of the missions we can see a microcosm of the larger impact of the earliest Indian slave trade.

By the mid 1520s, the Dominican and Franciscan dreams were over, and Tierra Firme had become a harvesting ground for Carib Indians. At the end of the sixteenth century, English, Dutch, and French explorers and settlers had mounted their own Indian slave trading operations in the region.Footnote 127 Meanwhile the Dominicans and Franciscans (and later the Jesuits) had moved on, concentrating their efforts in places like New Spain, Guatemala, Florida, and Río de la Plata.Footnote 128 Nevertheless, for a brief moment the coast of Tierra Firme was at the center of the Spanish evangelizing mission, an attention that forever altered the indigenous landscape of present-day Venezuela and Colombia and the shape of the Spanish empire.