INTRODUCTION

The working of representative democracy depends on political parties and on a number of functions they fulfil, the most important one being the structuring of the vote. The ideal type of representation through the mechanism of party competition sees parties offering alternative policy choices based on which citizens mandate them and hold them accountable. Representative democracy is thus primarily party government in which political parties represent—i.e., respond to people's preferences—and govern.

It is commonly accepted that, in recent decades, this mechanism came under strain. On the one hand, parties are blamed for having lost interest and capacity in representing the people and lost touch with their problems. On the other hand, parties are accused of having lost interest and capacity in governing responsibly focussing instead on short-term electoral gains. It is often claimed that parties’ difficulty at representing and governing originates from the radical transformations of politics and economy, particularly economic globalization, the nonstate character of governance, and the mediatization of political communication.

The consequent “crisis” of representation and government has been used by a number of observers to explain the challenge to parties by populism and its forceful claims to restore responsiveness in the political system.Footnote 1 Few, however, have so far analyzed a second type of challenge: technocracy and its claims to restore responsibility and effectiveness in the political system. After major but isolated contributions such as Centeno (Reference Centeno1993); Fischer (Reference Fischer1990); and Meynaud (Reference Meynaud1969), it is only recently that a renewed attention has been devoted to it (Dargent Reference Dargent2015). Yet a conceptual discussion of technocracy and populism is so far missing. To compare analytically both alternative forms of representation and juxtapose them to party democracy is the contribution of this article.Footnote 2

People or experts? First, the article aims to stress the analytical commonalities between the two forms of representation. Both alternatives are examples of “unmediated politics” dispensing with intermediate structures such as parties and representative institutions between a supposedly unitary and common interest of society on the one hand and elites on the other. Second, the article aims to identify the fundamental conceptual differences between the two, with populism stressing the centrality of a putative will of the people in guiding political action and technocracy stressing the centrality of rational speculation in identifying both the goals of a society and the means to implement them.

The analysis of populism and technocracy as alternative ideal forms to party democracy is addressed theoretically allowing for wide-ranging temporal and geographical illustrations. Both have continuously sided party democracy since its inception in the second half of the 19th century and turn of 20th century (Hicks Reference Hicks1931). Populist movements emerged in the United States as well as with the narodnik movement in Russia, and in Europe as Bonapartism first and fascism later. Right-wing populism has for long characterized Latin American politics after World War II. The last two decades have witnessed the rise of both right-wing populism through parties such as UKIP in Britain, National Front in France, Danish and Swiss People's Parties, and the Tea Party in the United States (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Skocpol and Coggin2011), and left-wing populism in Bolivarian clothes in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky, Roberts, Levitsky and Roberts2011; Weyland Reference Weyland2001), as well as in parties like the Five-Star Movement in Italy, Die Linke in Germany, Syriza in Greece, and Podemos in Spain. Noting this tide, some have spoken of a “populist Zeitgeist” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004) while others have related it to changing class structures and migration patterns (Betz Reference Betz1994; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012).

Technocratic and scientific ideals of societal management emerged from the organizational transformations that followed industrialization and Taylorism in the 1920s and 1930s in the United States and Europe. Today, “expertocratic” positions aimed at neutralizing political conflict as well as the regulatory state (Majone Reference Majone1994; O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994) are addressed in a broad literature on nonstate forms of governance, networks, and supranational agencies underlying the technical nature of policy making. Such accounts are complemented by the analysis of more specific expressions of technocracy such as nonpartisan executives in South European and Latin American countries (Centeno Reference Centeno1994; Centeno and Silva Reference Centeno and Silva1998; McDonnell and Valbruzzi Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014; Pasquino and Valbruzzi Reference Pasquino and Valbruzzi2012).

However, a systematic conceptual comparison of the analytical relationship between populism and technocracy from the perspective of political representation has not been attempted so far. Populism and technocracy are treated as ideal types in this article. Populism is defined as a form of representation claiming that political action must be guided by the unconstrained will of the people. Under this broad definition, the empirical referents can be (1) specific actors (leaders, movements or parties), (2) discourses and ideologies, (3) specific institutions or whole regimes that translate the populist conception of democracy into sets of institutions. The term “unconstrained” refers to the secondary role played in this form by checks and balances, procedures, and the constitutional protection of minorities (and of the opposition) against majoritarian or plebiscitarian decisions. Similarly, technocracy is defined as a form of representation stressing the prominence of expertise in the identification and implementation of objective solutions to societal problems. Again, empirical referents may include actors, discourses, or sets of institutions. While, strictly terminologically, the term “technocracy” refers to a form of power (whereby the competent, in identifying the means, is not necessarily neutral and impartial in identifying the goals) rather than to a form of representation, it is nevertheless maintained in the article.

The more or less explicit claim to rule according to different conceptions of representation are made sometimes explicitly by specific actors and sometimes in a more diffuse manner. Sometimes these actors do participate in the very representative institutions they challenge. Sometimes they create new institutions or regimes. In all cases, however, populism and technocracy offer alternative forms of representation to representative government as practiced through political parties. Both are defined in this article by their forms of political representation and legitimation of political action rather than by being protest movements or relying on a given style of communication (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007). The article has therefore a theoretical-analytical focus on political representation and treats party democracy and the two alternative forms of representation largely as ideal types.

The core argument of the article is that populism and technocracy present two alternative ideal forms of representation to party government. Both criticize a specific conception of representative democracy and, obviously, they challenge also one another in a triangular relationship. The article outlines the main features of representative democracy and the main dimensions of political representation in the first section. In the second section, it presents the broad shortcomings of party democracy at the origin of the critique from populism and technocracy. In the third and main section, the analytical comparison between the forms of representation is presented. It considers both similarities and differences between populism and technocracy, and how the two relate to the principles of party government.

THE PARTY MODEL OF REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY

The birth of representative democracy—indeed, its “invention” (Manin Reference Manin1997; Morgan Reference Morgan1988; Urbinati Reference Urbinati2006)—is an unprecedented attempt of incorporating increasingly vast segments of society into politics and state matters eventually leading to mass democracy with the full enfranchisement of national resident adults (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2005; Dahl Reference Dahl1956; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1970). As a new and original form of government (in the broad English meaning of the term), representative democracy has also proved extremely resilient to critiques (from elitist theorists such as Michels, Ostrogorski, Mosca, and Schmitt) and attacks from totalitarian (fascist and communist) mass mobilization between World War I and II.

The accounts by influential politically active thinkers such as Burke, Madison, and Siéyès, among many others, in the countries in which representative government appeared first are early examples of “institutional engineering” of a new type of government. In England, the United States, and France representation became formally organized through a vote (as opposed to the lot or direct democracy) for a parliament of a certain size, in territorial constituencies and without the imperative mandate. Even though in many countries estate bodies were initially maintained (for the aristocracy and clergy in particular), in the course of the 19th century general, individual and equal representation imposed itself over plural voting based on wealth and education. The vote became the central institution linking represented and representatives and thus the core feature of institutions we still call representative government or, simply, democracy 200 years later.

While classical political philosophers like Rousseau thought democracy workable only in small city-state settings, more pragmatic theorists were able to establish a link between citizens (as principals or “constituents”) and representatives (as elected agents) workable also in large populations. While not “government by the people” strictly speaking, this form of government was considered as having the advantages of a specialized and more competent elite in Schumpeter's terms (a “democratic aristocracy” as Manin has labelled it) able to devote time to state functions in the social division of labor.Footnote 3 In addition, debate and deliberation (in, as it were, “parliaments”) would lead to superior decisions in the general interest of the nation. Precisely this requirement of expertise and competence is one of the arguments that led institutional engineers to dismiss the lot as a mechanism for the selection of representatives—the other reason being that only through the vote can there be the necessary formal expression of consent authorizing representatives to act on behalf of citizens.Footnote 4

To address the ideal-typical representative features of populism and technocracy in alternative to the party model of representation, it is useful to start from Pitkin's conceptualization (Reference Pitkin1967), according to which political representation can be separated into three types:

-

• Through descriptive representation the diversity of society is represented. Governmental bodies should roughly correspond to, if not perfectly mirror, the demographic and socioeconomic composition of society for which sampling could in fact be a more efficient method. Emphasis is placed on “being” rather than “doing.”Footnote 5

-

• Through symbolic representation the unity of society is represented. Symbols embody the identity or “essence” of peoples and nations, and involves the construction of myths through various narratives. It is a top-down process fostering legitimacy for the superiority of the “whole” over its parts with emotional and irrational elements of socialization and indoctrination. Such processes can be observed in totalitarian and mass-democratic regimes (nation-building).Footnote 6

-

• Through active representation the interest of society is represented. Elections are the expression of interests and preferences, as are the actions of representatives. The emphasis is placed less on “being” than “doing,” i.e., an authorized action on behalf of citizens. Such action does not require being similar to citizens sociologically. On the contrary, the complexity of state matters may require higher intellectual qualifications on the part of representatives compared to the population.

Of particular relevance in regard to the question addressed in this article are the debates revolving around this last point, namely the scope of such authorization: “acting on behalf” can be interpreted more or less restrictively.

At one extreme of the continuum, one finds the delegate model of representation in which representatives act on grounds of a mandate on the part of the constituents.Footnote 7 The mandate assumes that citizens are able to make judgements and instruct representatives to act accordingly. The focus is less on accountability (after all, politicians do as instructed and cannot be blamed for citizens’ decisions) and more on responsiveness in that politicians act congruently with citizens’ preferences. At the other extreme, one finds the trustee model of representation in which representatives act independently from a mandate. Independence assumes that citizens have neither the necessary expertise nor the time to make informed decisions and thus authorize experts to decide for them. The choice of representatives is therefore not primarily based on the contents of a “promise” but rather on perceptions of competence and trust. The focus is less on responsiveness (after all, politicians cannot be expected to act congruently with preferences that are not expressed in a mandate) and more on accountability in that politicians are judged on their performance retrospectively. Table 1 summarizes these two extremes.

TABLE 1. Delegate and Trustee Models of Representation

The table highlights the tension of the party model of representative government between demands for responsiveness and demands for responsibility noted by various authors starting with Dahl (Reference Dahl1956) and continuing, among others, with Birch (Reference Birch1964) who notes the gap between responsive and responsible government in Britain, and leading to Scharpf's (Reference Scharpf1999) distinction between democratic and efficient government.Footnote 8 The core of this tension lies in the difficulty—under democratic conditions—to optimize the dimension of responsibility while at the same time be responsive to citizens which may have preferences that are not aligned to such decisions.

As famously noted by Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1942), political parties have long been ignored both in philosophy (the “orphans of political philosophy” according to the more recent assessment by Rosenblum (Reference Rosenblum2008)) and legal studies (focussed on state institutions and their formal procedures). Yet “modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties” (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1942, 1). Similarly, Sartori argues that “citizens in modern democracies are represented through and by parties” (Reference Sartori1968, 471).Footnote 9 Political parties—which originated within and outside parliaments to run elections, organize campaigns, and form political personnel—assume the primary function of structuring the vote in that they articulate interests and preferences, aggregate demands from various sectors of society, in more or less coherent ideologies, and formulate policy programs.

First, it is the parties that operate these aggregations. Second, it is the differences between party programs that offer alternative choices which they prospectively promise to enact and on which they are retrospectively held accountable. Party government thus constitutes a weaker variant of the mandate model whereby citizens choose between proposals made by representatives who are to a large extent bound by them if asked to translate them into policies. While the imperative mandate has been ruled out from the legal framework in Western democracies, outside the legal circuit of representation political parties enabled citizens to “mandate” representatives by voting or not voting for alternative platforms.Footnote 10

This arrangement came to be known as the responsible party model following an influential publication by the American Political Science Association (APSA 1950). The linkage between citizens and politicians is assured by having two or more parties in competition offering distinct packages of policy alternatives, so that voters can make a meaningful choice based on the proximity with their own preferences in an ideological space. The vote for a platform is seen as a “contract” that binds the party vis-à-vis the electorate. Based on this competition a party or coalition controls the executive and public policy is determined by parties in the executive. The “contractual relationship” (Pierce Reference Pierce, Miller, Pierce, Thomassen, Herrera, Holmberg, Esaiasson and Wessels1999, 9) between party and electors is thus strongly defined and the responsible party model implies “an intense commitment to a mandate theory or representation” (Converse and Pierce Reference Converse and Pierce1986, 706). It is also clear that such a model finds its application mostly in political systems defined by proportional representation in Western Europe and less in the United States, where parties are less structured and cohesive, less nationalized and where competition is prevalently district based.

THE POPULIST AND TECHNOCRATIC CRITIQUE TO PARTY GOVERNMENT

It appears that political parties play a central role in the democratic representation mechanisms. On the one hand, parties fulfill the function of structuring the link between citizens and representatives by articulating interests, values, and cleavages, and by offering alternative and coherent proposals for the aggregation of society's plural interests and preferences (ideological proximity, congruence, and responsiveness). This assures input legitimacy with contractual and binding promissory elements. On the other hand, parties fulfill the function of governing responsibly and competently by forming political personnel through the rank-and-files of party organizations and by providing societal projects, Weltanschauungen (in a word, ideologies) which aggregate the plurality of interests and values. This assures output legitimacy.

The analysis of populism and technocracy should therefore start with their critique of the alleged shortcomings of parties. Their transformation from “mass” to “cartel” (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995) has been used to stress the widening gap between parties’ representative and government functions. As parties relocate from close to society to close to the state, their executive role is strengthened—that is, the function of government at the expense of the function of representation (Bardi et al. Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2014a; Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2014b; Mair Reference Mair2009; Saward Reference Saward2010). In their relationship to the electorate, parties are out of touch because they find it difficult to read and aggregate preferences, the external constraints on policy alternatives are considerable (in particular from supra- and transnationalization) and changing communication patterns diminish parties’ capacity to foster loyalty. Parties become representatives of the state rather than the people.

This view highlights the populist critique to party democracy. Yet it neglects the technocratic critique. From this perspective, parties are not out of touch with electoral demands in an age of constant monitoring of public opinion through increasingly sophisticated means including polls, marketing tools, and social media. Similarly, in spite of having lost mobilization capacity through dense organizational networks and active membership, parties have an array of other means to persuade voters and foster loyalty through innovative channels of communication and information. Therefore, to the argument that parties are busy governing and thus change from being an agency of social mobilization to an agency of the state, it is countered that parties are busy winning elections by following public opinion and, once election is secured, disregard governmental functions or, at best, tailor policies to the goal of re-election. In this view, only competition matters and therefore parties become over-responsive, not less responsive.

The critique to party representation must therefore consider both the populist and technocratic sides. On one side, parties are presented as less responsive to the public especially during periods of high corruption and economic crises. This is the view taken by populist mobilization. On the other side, however, parties are also presented as less responsible by acting predominantly to seek popular consent. This is the view calling for experts to take over. In both cases, parties are seen as noncredible. In the first case, parties are considered as nonresponsive because they are accused of shifting from society to government. In the second case, they are seen as irresponsible because of the need to run after the moods of public opinion and short-term responsiveness dominated by media's needs and the requirement to display immediate results in high-frequency electoral cycles in multilevel arenas.

What are the elements on which populism and technocracy base their critique of party democracy? Three broad factors can be mentioned.

The first factor is “electoralism.” Parties are accused of abandoning many of their representation and governing roles in favor of the goal of increasing electoral support, winning governing positions and distributing the spoils of victory. Such priorities involves patronage, monitoring electorates through increasingly sophisticated polling instruments as well as—in the case of incumbents—policies aimed at short-term (usually economic) results to secure re-election. As only electoral competition matters, this strategy involves a high degree of responsiveness or, to put it in a less positive light, running after the populace's moods.Footnote 11 Programmes’ and policies’ prime goal is not responsible decision making in the terms defined above but rather capturing electoral support by bending their action to electoral advantage. Technocracy is then invoked as the solution insofar as it involves decision makers who are not subject to the tyranny of popular consent.

Viewed from a technocratic perspective it is thus limiting to consider parties as having simply morphed into governing parties and therefore challenged by populist movements that aim to re-establish the centrality of people. Parties are first and foremost seen as electoral machines.

The second group of factors comprises of a critique of “governance.” Already this term evokes a higher degree of complexity—indeed, technicism—than “government.” The governance structures that go under the label of type II governance (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2003) involve intersecting cross-territorial jurisdictions at all levels of the multilevel state structure (Kohler-Koch and Rittberger Reference Kohler-Koch and Rittberger2006). They include international organizations and courts, transgovernmental networks and agencies, independent regulatory authorities, think tanks, etc. These modes of governance provide a fertile soil for populist critique. Citizens are presented as feeling distant from processes that are complex, nontransparent and lacking democratic legitimacy, all of which justifies malaise and antiestablishment discourses.

From a technocratic view, however, complexity calls not simply for more popular participation but also for less and for entrusting its management to experts. Not only are parties presented as unable to deal with complexity through their diminished capacity to form expertise, but also as bound to supra- and non-national governance which involves a number of policy constraints that limit anyway the possibility for them to act beyond a merely managerial role which the political personnel may as well leave to experts. Not only populist protest, therefore, but also calls for technocratic management.

The third group of factors can be labelled “mediatization.” For the most part, mediatization has been analyzed in its effects on the style and professionalization of political communication by parties, governments and leaders (Esser Reference Esser and Kriesi2013; Krämer Reference Krämer2014; Mazzoleni et al. Reference Mazzoleni, Stewart and Horsfield2003; Voltmer Reference Voltmer2012). This has reduced the significance of party apparatuses, militants, and the traditional channels in favor of new and social media in which direct possibilities of communication between leadership and audience personalizes politics.

Mediatization supports the critique that parties and leaders have increased their capability to keep in touch with electorates and that new media strengthen the responsiveness to people's preferences. This, however, does not seem to mitigate the critique. In spite of the opportunities offered by new media, politicians and parties are presented as nonresponsive. Rather than allowing parties to stay in touch with the electorate, mediatization has made it possible for populists, sometimes individual mavericks, to justify bypassing parties, raise critique, and continuously bring up new issues which parties themselves are not aware of and do not foresee. Political parties and their leaders should not have the monopoly of the agenda and give up one of their core but “distortive” functions, namely that of “gatekeepers.” The public sphere is encouraged to become more assertive and to mobilize large groups of citizens. It has become easy to stage protests and present parties as distant. What the populist critique encourages is a politicization beyond, outside, and independently of partisan cannels, which parties should not control, should not anticipate and, consequently, to which they cannot be responsive.

Mediatization affects also responsible government. The constant scrutiny of parties’ actions forces them to focus on short-term results, policies, and proposals that can be easily sold on the media market place. In a context in which parties control the agenda and are gate-keepers, necessary but unpopular policy programs can be pushed through and explained. In a context of immediate criticism by a plethora of independent media sources such attempts are suicidal. Furthermore, communication skills and efforts in “self-mediatization,” rather than governing expertise in various policy areas, take the fore in the traits leaders must display. Under these conditions responsible (“backstage”) government retreats in political parties’ priorities.

The representation model of party democracy is thus criticized from two sides. On the one hand, mediatization undermines their ability to respond to electorates’ demands in spite of electoralist efforts to court them by being over-responsive. On the other hand, the very electoralist strategies undermine their ability to govern responsibly and navigate the complexity of network governance. Consequently, from one side their role as crucial actors of representative democracy is attacked by populist ideologies. From the other side, their governing role is attacked by calls for technocratic expertise. The main section of the article addresses the way in which these alternatives are articulated in different understandings of representation in populism and technocracy.

THE POPULIST AND TECHNOCRATIC ALTERNATIVE FORMS OF REPRESENTATION: AN ANALYTICAL COMPARISON

While the populist theory of democracy has often been juxtaposed to liberal constitutional government, the technocratic alternative view has been largely neglected. Authors have compared populism and liberalism (Riker Reference Riker1982), popular and constitutional democracies (Mény and Surel Reference Mény and Surel2002), delegative democracy and polyarchy (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994), democracy and populism (Urbinati Reference Urbinati1998), populist and party democracy (Mair Reference Mair, Mény and Surel2002), or, most famously, populistic and Madisonian democracy (Dahl Reference Dahl1956). All stress the illiberal and unmediated character of populism, and its strongly majoritarian nature deprived of checks-and-balances and constitutional protection of minorities, the unitary conception of the demos, and the prominence of people's will over procedures and the rule of law.

In this section, it is not claimed that such an opposition does not exist but rather that it is incomplete as the alternative to representative democracy as expressed in party government comes also from technocracy as a form of representation. The relationship is triangular. While the two alternative forms have a great deal in common, there are also a number of crucial differences and therefore must be analyzed as form of representation.

As already mentioned in the Introduction, populism and technocracy are neither new concepts nor new phenomena. Both have antique intellectual and institutional origins, and for both it is possible to find utopian writings up to the present time. As illustrations, one can think of Plato's conception of politics as technique to be handled by philosophers-kings, Francis Bacon's New Atlantis and the tribunes of the plebs in the Roman republic. More importantly, populism and technocracy emerged in parallel to, and coexisted with, representative democracy and party government after the National and Industrial Revolutions of the 19th century.Footnote 12 Ever since, they have been constant political and philosophical features of mass politics.

Populist movements and parties emerged in places as distant as Russia (the narodnik movement around 1875), North America (the People's Party in the South and Midwest between 1891 and 1912), Europe in the form of Bonapartism in the 19th century, fascist movements after World War I, Poujadism and the Uomo Qualunque in France and Italy, respectively, after World War II. In Latin America populism appeared in various ideological forms and sometimes with the transformation from movement into regime in the course of the 20th century as in the case of Vargas in Brazil, Peron in Argentina, and the APRA in Peru.

Technocratic movements appeared as a consequence of the organizational revolution that industrialization brought with itself (Taylorism and scientific management) and the general bureaucratization of state and market. In part it is in response to agrarian populism that technocratic soviets or committees on technocracy have been theorized in the United States by Thorstein Veblen, Walter Rautenstrauch, and others. Scientific Marxism and the role of the vanguard can also be seen in this light (with its strong reliance on reason). In sociology it is possible to follow a similar thread from Saint-Simon to Comte and Karl Mannheim (Fischer Reference Fischer1990; Reference Fischer2009), to more recent contributions on “expertocracy” and “problem solving” approaches aimed at neutralizing conflict (O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell1994) and on the “regulatory state” based on rule making, monitoring, and implementation by the state (Majone Reference Majone1994), which some consider as associated to a neoliberal agenda (Crouch Reference Crouch2011).Footnote 13

Both, ultimately, are forms of power—in the populist case the power of the people, in the technocratic case the power of experts. Power in technocracy derives from abandoning neutrality or impartiality (Rosanvallon Reference Rosanvallon2011) by setting the goals of political action beyond merely establishing the means, with stronger or weaker manifestations—from dirigisme and planning to meritocracy and consultancy of experts. While the former places its emphasis on popular will as the ultimate justification of political action, the latter places it on knowledge and expertise. Not only liberal constitutional democracy vs. populist democracy, therefore, but also “democracy versus guardianship” (Dahl Reference Dahl1985).

While the literature has extensively analyzed populism and technocracy as forms of power, little has been devoted to the systematic analysis of their conception of political representation. The analytic comparison of the populist and technocratic forms of representation—their commonalities and differences—is the goal of this section.

What Populism and Technocracy Have in Common

Populism and technocracy see themselves as antipolitics and, more specifically, antiparty. Whether in their actor (movements and parties), discourse and ideology, or regime and institutional versions, both forms of representation claim to be external to party politics. In fact, the more precise claim of these forms of representation is that they are above party politics, which is seen in negative terms for various reasons. Parties are carriers of particular interests rather than the interests of society as a whole and even pursue the interests of the “part”—as it were—to the detriment, when necessary, of the general interest.Footnote 14 Parties, rather than being perceived as capable of formulating visions and projects for the common good of the society (albeit alternative ones), are seen merely in terms of individualistic and self-interested (ultimately irresponsible) factions that articulate particularistic interests.

Furthermore, as seen in the critique above, parties’ main goals are identified with electoral competition and the occupation of government positions rather than political action for the common good. They are seen as a distortive element in the link between people's interests and decision makers. The first studies of political parties have stressed the negative impact of both “factionalism” and “compromise” (Michels Reference Michels1911; Ostrogorski Reference Ostrogorski1902) echoing the classical tradition from Rousseau to Schmitt but that was contested by Kelsen and, later, Schumpeter who argued against the organicistic view of society and the idea of a common good.

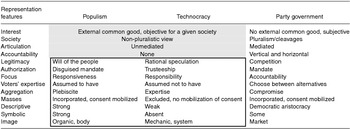

Four ideal-typical common representation features are at the root of populism and technocracy (common elements between the two appear in the shaded area in Table 2).

TABLE 2. Party government, populism and technocracy: similarities and differences

Legend: shaded area = commonalities between populism and technocracy; bold box = differences between populism and technocracy.

First, in both populism and technocracy there is the idea of a unitary, general, common interest of a given society (a country).Footnote 15 In these views, there are things that are either good or bad for the whole of society and political action can be either good or bad for a society in its entirety. There is a homogenous and organic vision of the people and the nation. It is furthermore possible to “discover” this common or general interest. While populism and technocracy—as is discussed below—have fundamentally different views on how to identify the unitary interest, they are confident that it exists and can be found out.Footnote 16

Second, both populism and technocracy have a nonpluralistic view of society and politics. Politics is doing what is good for all, not articulating, allocating and deciding between diverse interests, or aggregating them. To be more precise, an aggregation does indeed take place. However, rather than having competing proposals of aggregation (as this is the case in parties’ ideologies) given to people to choose from, the true solution is manifest and indisputable. In this sense, both pretend to be, and present themselves as, anti-ideological. There are no party platforms needed (for a prospective decision) and, when and where these are available, they should not be binding. To be sure, mass political parties, too, present a unified vision of the public interest. This is precisely their function of “aggregation” of various interests from diverse constituencies. However, differently from populism and technocracy, several visions are present in the system, they compete with one another and compromise is sought—either through majority-opposition alternation over time or consensual institutions.

While party government is mainly based on a prospective “mandate” view (input counts and parties are bound to what they promise), populism and technocracy are based on a retrospective “independent” view (output counts) as they operate through vagueness rather than through a precise program or mandate.Footnote 17 Both populism and technocracy thus follow a trustee model. In technocracy, people cannot give a mandate because they do not possess the faculty of identifying society's interest. In populism, it could be argued that the leadership determines people's interests through a strong identification with them (embodiment)—by being “one of them.” This can be seen as a form of mandate. Yet there is a complete transfer of decision making to the leadership that is unquestioned. Questioning the leadership is automatically questioning the will of the people. In the party government conception of democracy, on the other hand, voters are assumed to have some degree of expertise.

Third, both populism and technocracy—in their vision of a unitary society and refusal of plurality—see the relationship between people and elite as “unmediated.” All that comes in-between is a source of distortion of the general interest.Footnote 18 As a consequence, populism and technocracy rely on an independent elite to which the people entrust the task of identifying the common interest and the appropriate solution. In spite of presenting themselves as antielite and antiestablishment, the populist model is as elitist—if not more—than party government with leaders being uncontested and unquestioned over protracted periods and enjoying vast spaces to manoeuvre and freedom to interpret people's interest. It is no accident that populist parties—be it in the past or recently in Austria's FPÖ, France's National Front, Italy's Northern League, or Britain's UKIP among others—have lasting leaderships that are largely uncontested and based on acclamatory and plebiscitarian mobilization. In fact, both types of ideologies have often found their application in nondemocratic regimes, most notably in Latin America, be it the populist-plebiscitarian regimes or the technocratic-military regimes.Footnote 19

Fourth, both forms of challenges dispense with accountability. Usually, two dimensions of accountability are distinguished. Vertical accountability refers to the possibility of voters to sanction representatives. As is mentioned below, the populist conception of representation is based on elites and people being “one”, while the technocratic conception is based on elites being separate from the people. In both cases, however, the idea of people sanctioning elites does not apply. In the populist case it would mean a self-sanction. In the technocratic case people do not have the capabilities to judge the action of elites and thus should not be in the position to sanction them. Horizontal accountability, on the other hand, refers to the possibility of constraining elites’ action through the rule of law and human rights, checks-and-balances, and international treaties. For both populism and technocracy the interest of the whole of society has priority and therefore should not be constrained by procedures.

What Makes Populism and Technocracy Different

Contrary to the pluralist vision of democracy as party government interprets it, populism and technocracy believe—as just seen—in the existence of an “objective” interest of society which can be determined independently of the expression and channelling of “subjective” interests. While party government relies on voicing and aggregating plural attached interests, populism and technocracy rely on other mechanisms for the identification of the objective and comprehensive interest of society. This is where both differ from party government. This is also where they start differing from one another.Footnote 20

How do populist and technocratic forms of representation establish what the objective interest of society are? How, in other words, can they establish what is good for citizens if they distrust the articulation of plural interests and competing party proposals for societal projects? After all, as seen above, both forms believe in an “external” interest, detached from the specific group interests and their aggregation. To this question populism and technocracy give radically different answers.

For populism, the general interest can be identified through the will of the people. For technocracy, the general interest can be identified through rational speculation and scientific procedures. In populism, therefore, the claim of responsiveness is at its maximum and in technocracy at its minimum. The people, in the technocratic view, do not have the time, the skills, or the information to be able to determine what is best in their interest. Representation defined as “acting for,” on behalf of, the people (substantive representation) thus requires a full trustee/fiduciary model in which responsiveness takes a second-order position vis-à-vis responsibility and governing functions. Objective solutions refer here to the independence of such solutions from citizens’ preferences and to their “general” nature, namely for the whole of society.Footnote 21 In the populist view it is the other way around with responsibility giving way to responsiveness. However, while the claim of responsiveness would in theory require a full mandate model from the will of the people to the action of leaders, in practice the very “will of the people” is often determined by the leaders themselves or, at least, interpreted by them on behalf of the people. It is in this sense that the “will” is putative (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010).Footnote 22 This is particularly the case when the will of the people is extrapolated from a majoritarian or plebiscitarian vote whereby the majority is equated with society as a whole and thus not requiring the protection of minorities, various devices of checks-and-balances, control of constitutionality and international law – i.e. the horizontal accountability.

A number of consequences follow from this first difference. In the populist form descriptive representation (the degree of correspondence between the demographic and socioeconomic features of represented and representatives) plays an important role insofar as “being one of them” helps the symbiosis with the “common men,” understanding their needs and moods and embodying them. The strong element of incarnation of the popular will by leaders relies precisely on descriptive similarity. This probably explains to a large extent populist communication strategies and styles by populist leaders stressing similarity to the people in clothing, speech, and lifestyles on which so much of the literature on populism insists. On the contrary, in the technocratic form descriptive representation should be minimized. Technocrats are supposed to be better educated, more knowledgeable, and possess expertise that common people do not have. Under populism, therefore, a maximum of descriptive representation is required while, under technocracy, a minimum of it is desirable. The trust on which the delegation to representatives is grounded has different foundations: in populism people trust them because “they are like us” while in technocracy precisely because “they are not like us.”

The literature on political representation has discussed the point about descriptive representation at length. Importantly, the “to be” (standing for as in descriptive representation) does influence the “to do” (acting for as in substantive representation). Burke himself, who was opposed to suffrage extension and insisted on the qualities of the elite, acknowledges that a certain degree of correspondence between represented and representatives is necessary as this presence informs the assembly about the needs and the views of the population (as in the case of Irish Catholics and American colonist in the time of Burke's writing).Footnote 23

Repeatedly, in this article, it has been mentioned that for populism the legitimacy of political action is derived by an organic notion of the people's will, yet that such a will is “putative,” namely constructed by actors and, where populism became a regime, by a state that fosters a comprehensive totality and unity in which social and political pluralism as well as class or ideological differences are denied. This organic notion of the body politic strongly relies on symbolic representation and the emotional and affective attachment, and thus on a conspicuous element of irrationality, blind belief, and uncritical predispositions. A strong reliance on the concept of an organic, comprehensive totality of the people, necessarily involves socialization, even indoctrination, to push the integration of the group and uncontested loyalty to it. It is in this “top-down” flow typical of symbolic representation, that populism makes a more direct use of distinctive and exclusionary ethnocultural, historical and mythological traits.Footnote 24

Being legitimized by “output,” does technocracy need a comparable reliance on symbolic representation? This is more difficult to answer but probably technocracy does not need the symbolic mobilization of citizens to the same degree as populism. To be sure, the image of society that technocracy puts forward is no less constructed than the one populism creates, even if less explicit and presented in the cold light of objective rationalism. The image can vary but always refers to something that can be steered, regulated, managed, and “fixed.” This image alternatively refers to society and politics in particular as machine, system, network, and so forth. It is a different image than the populist one because it allows for greater complexity (in a way, it allows for pluralism, though it is not a pluralism of interests but rather of roles and functions). In this image efficiency is predominant and pervades the goals technocratic government sets beyond the means it identifies to reach them as, for example, in the case of economic and monetary policy, immigration policy but also, in extreme cases, demographic policies such as eugenics.Footnote 25 Yet, in spite of relying on a clear image of society, technocracy does not seem to require the same effort of people's emotional mobilization through symbolic top-down representation.

Populism and technocracy further differ in their relationship to the mass citizenry and electorate. The distinctive feature of populism is the direct and continuous mobilization of the people either institutionally through—typically—direct votes such as plebiscites or via noninstitutional channels (polls, new social media, acclamation, etc.). These “votes” serve the purpose of renewing consent, not express preferences. In this sense, it is a trustee model—so, a maximum of inclusiveness even if practically this is often not possible (or not desired) and therefore replaced by stratagems of impersonification through a charismatic leader. The distinctive feature of technocracy, on the contrary, is the indirect and at best intermittent involvement of the people. So, a minimum of inclusiveness.

Table 2 summarizes the arguments schematically and allows us to wrap up the article. Populism's core representation feature is responsiveness (albeit referring to a putative popular will). If leaders fully respond to people's preferences and, in fact, simply implement them in a fully fledged mandate there is little need for accountability. People should blame themselves, not politicians who did what they were “instructed” to do.Footnote 26 In other words, accountability is simply on the input side in case politicians betray the putative mandate. In party government, on the contrary, accountability is on the input side (if parties betray their promises) but also on the output side since parties are supposed to provide the alternatives for choice from which people choose. In proposing these programs they are also selectively responsive (to their core constituencies in particular). People cannot blame themselves if parties are unable to provide good programs.Footnote 27 In technocracy, finally, government does not act on a mandate—it is, ideal-typically, the exact opposite of responsiveness—but rather claims to act in the best interest of society. Neither is technocracy accountable because people do not have the competences to evaluate its performance on any indicator (and obviously not on the basis of betrayal of a program since there is no promise or mandate).

Technocrats act according to a trustee model. Populists act, in the ideal type, according to a delegate model. In reality, populists are asked to interpret and form the popular will so that ultimately they also act according to a trustee model. In Table 2 this is labelled “disguised mandate.” The vote is plebiscitarian and serves uniquely the purpose of mobilizing support and renewing consent, not to mandate. Formally, there is no mandate also in party government but parties are supposed to govern according to a promise/program. The vote for this promise/program constitutes a mandate.Footnote 28 It was mentioned above that parties are selectively responsive. This points to the pluralist nature of representative democracy and party government. There is no unitary vision of a volonté générale nor is there a unitary vision of a society's common interest. There are societal cleavages that must be articulated and aggregated.

The table mentions that the aggregation of diversity occurs through compromise. This is meant in broader terms than consensus, centripetal or “consociational democracy” as intended by Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1977; Reference Lijphart2012) or Horowitz (Reference Horowitz1985). Compromise refers here to the a broader set of possible arrangements between majority and minority(ies), or oppositions. Such arrangements can occur to different degrees. What one usually labels majoritarian democracy (Westminster) is one extreme in which minorities are largely (albeit not totally) excluded from the governing function (Powell Reference Powell2000). Yet they do have rights and there is legal protection. Their opposition is legitimate and a degree of involvement in policy exists. However, compromise occurs mainly through the alternation over time between government and opposition. Consociational or proportional democracies are the other extreme in which minorities are continuously included in decision making and consensus is actively sought. For this, the mediation through parties and representative institutions is necessary.

Majoritarianism under populism should not be considered authoritarian because it stems from the majority, but it is “illiberal” as, in its ideal form, it is unconstrained by checks-and-balances, procedures, international conventions, and other features of horizontal accountability. This vision of democracy is inimical to liberty as it equates the will of the majority with the comprehensive totality of the people. Technocracy in its extreme form is authoritarian as it does not involve the support of the majority of the population. The so-called “democratic deficit” of the European Union, for example, is imputable to the technocratic perception of it. Furthermore, it is expected that technocrats are demographically very different from the majority of the population.Footnote 29 On the contrary, since populists are supposed to impersonate the people it is expected that they are like them. In party government, descriptive representation is intermediate. There should be expertise but descriptive representation has an important informative (in Burke's sense of informing a rational deliberation between experts) and egalitarian function (a “democratic aristocracy” in Manin's sense).

Finally, legitimacy. The article has discussed at length that legitimacy in populism derives from being based on the affirmation of people's will and that legitimacy in technocracy derives from being based on rational speculation. What about legitimacy in party government? There is, as in populism, the legitimacy coming from the vote of the people. However, in representative government, this would be void if competition did not exist. Incorporation (universal suffrage) must be accompanied by the dimension of liberalization (competition). This involves not only competing parties but also alternative sources of information, and freedom of association and expression. In one word, civil liberties. In this, representative democracy is liberal and similar to other sectors of society that derive their effectiveness from competition: the trial in law, the market in economy, critique in science, and so on. Competition then simply refers to the mechanism through which the common good emerges from the pursuit of private interests.Footnote 30

CONCLUSION

A number of fundamental transformations in the past decades have reinvigorated the need to define analytically two alternative forms of representation to the party model of representative government that have been present since the development of mass politics in the 19th century in Europe and the Americas. This article has shown that, while populism and technocracy are in many respects opposite ideal forms of representation, they also share a number of commonalities. In doing so, it has combined the dimensions of representation with the theoretical discussion of the role of political parties in democracy.

To conclude a theoretical article, one may ask how radical is this double challenge in reality and whether or not it is an antisystem one? In different ways, populism and technocracy are both antipolitical forms of representation. While politics is competition, aggregation of plurality and allocation of values, populism and technocracy see society as monolithic with a unitary interest. While populism and technocracy aim at discovering the common good, parties compete to define it. Both populism and technocracy do not conceive of a legitimate opposition insofar as that would involve conceiving of “parts” being opposed to the interest of the whole. In the case of populism, plurality is reduced to the opposition between people and elite. In the case of technocracy, plurality is reduced to the opposition between right and wrong. In the former, opposition is corrupt; in the latter it is irrational.

For the sake of the theoretical argument, the article has presented the populist and technocratic alternatives to party government through ideal types rather than empirical cases. For sure, the technicization of political decision making is undermining democratic sovereignty and the popularization of politics and the public sphere is undermining the informed and respectful participation of citizens in favor of mob-type attitudes. However, in recent times this challenge has so far remained within the frame of the liberal democratic state. In contrast, between World War I and II many West European countries experienced a breakdown of democracy and many countries in Southern/Eastern Europe and Latin America had protracted periods during which regimes based on either or both populist and technocratic principles ruled. Today, populists mobilize as political parties themselves and participate to the electoral competition as well as national executives. Experts are co-opted by parties (often from think tanks linked to them) that rely on their expertise and delegate the task of taking unpopular decisions especially at the transnational level. There have been cases, as in Italy after the Monti cabinet of 2011−12, of experts creating political parties. By participating in elections, they offer precisely the kind of “agonistics” that legitimize the system and, when they enter government, movements and experts morph, vindicating party democracy.Footnote 31 Populism and technocracy therefore operate as “correctives” of—not only alternatives to—party government (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012).

The article has also shown the difficult current position of parties in this “stranglehold” between populist and technocratic challenges calling for more responsiveness and responsibility respectively. The party model of representative government, in fact, has long been successful in bridging these two crucial dimensions of representation and striking the necessary, if imperfect, balance between them. Today, parties are stretched between these dimensions and struggle to respond to the unbundling of the nation-state's boundaries as a political and economic unit. Ultimately, however, representative government requires a balance between people's mandate, competition, and expertise—what liberal constitutionalism has achieved by complementing people's will with procedural safeguards for pluralism and with representative democracy.

To strike this balance political parties play a crucial role even if they have lost their shine both among the public and political scientists. Some parties will succeed while others will fail in fencing off the double challenge they are confronted with and in balancing demands for more responsiveness and expertise. A convergence is not unconceivable. Populists acquire expertise as they assume institutional roles while technocrats cannot ignore voters’ preferences. What the past teaches is that articulated party organizations, the formation of competent political personnel, familiarity with state matters, experience with campaigns and communication, public funding and—perhaps most importantly—broad societal visions addressing all parts of society are, in the long term, great assets to strike the balance. This gives established parties an advantage over newcomers and sectoral experts but it is not excluded that new actors acquire similar assets and become the future established parties. This gives the system its flexibility and adaptability. Ultimately, therefore, these are assets for the entire democratic system, which it would be costly to squander. Since their appearance with mass democracy, parties have been successful in adapting to change. There are good reasons to believe that this form of representation will weather also the current challenge.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.