By virtually all accounts, the international human rights regime is deeply politicized. Generally speaking, politicization describes a situation in which principled neutrality is compromised in favor of political discretion. In the human rights regime, this occurs when decisions to “name and shame” human rights violations do not reflect the impartial application of central values and agreements (e.g., the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) but rather the political interests of individual states (Donnelly Reference Donnelly1988). The regime is “politicized” insofar as governments condemn human rights violations selectively based on their strategic relationship with the violator. United Nations (UN) forums are especially prone to allegations of bias and double standards. “Politicization,” Valentina Carraro writes, “is Geneva’s worst kept secret” (Reference Carraro2017, 965).

That human rights are politicized in this way is hardly surprising for many international relations scholars. As E. H. Carr taught us, because states act primarily to further their own interests under anarchy, “supposedly absolute and universal principles [are] not principles at all” but rather “the transparent disguises of selfish vested interests” (Reference Carr2001, 80). From this realist perspective, politicization is an expected and invariant fixture of the international human rights regime: for any given violation, states will turn a blind eye toward strategic partners while inflicting harsh punishments on rivals.

In this paper, we show that politicized enforcement is not a fixed attribute of the human rights regime but rather a dynamic phenomenon that varies markedly across different norms. For example, we find that states are more likely to punish abuses related to physical integrity, civil and political rights, and migration when the violator is a geopolitical adversary, all else being equal. But other norms—including socioeconomic rights, women’s rights, and children’s rights—are enforced more frequently between geopolitical friends. Thus, not only are some norms more politicized than others are, states are actually more likely to condemn their friends and allies for certain violations. Such patterns defy the conventional account of politicization, which envisions interstate human rights enforcement as a simple function of geopolitical relationships.

We develop a theory of politicization that accounts for variation in the effect of geopolitics on human rights enforcement. When deciding whether to punish a violation abroad, states face a dilemma between their image as global human rights promoters and their interests in important political relationships. Although states can collect social rewards by signaling a consistent dedication to universal norms, they also want to spare their strategic partners from damaging human rights pressure. To navigate this dilemma, states enforce various human rights norms discriminatively based on how sensitive they are for the target state. Shaming on some issues is more sensitive by directly threatening the target regime’s political legitimacy, survival, or control. Safer issues are those that are perceived as less threatening and thus more tolerable to target authorities. The upshot is that politicization—that is, the effect of geopolitical ties on the likelihood of norm enforcement—is conditional on the perceived sensitivity of the specific norm in question.

We evaluate the argument using data from the most elaborate multilateral human rights enforcement process in the international system: the UN Universal Periodic Review (UPR). In the UPR, governments voluntarily subject their human rights record to the scrutiny of their peers, who offer feedback in the form of specific recommendations. We examine over 57,000 recommendations from the first two cycles of UPR (2006–2018), tracking the influence of geopolitical relations in this process. Consistent with our theory, we find that reviewing states enforce human rights norms against both friends and adversaries, but exercise selectivity on the kinds of issues they address. States push adversaries on highly sensitive human rights issues, such as those that could potentially undermine the regime’s legitimacy or ability to suppress political competition. Safer issues, including socioeconomic rights and protection of vulnerable populations, are reserved for friends and allies.

This article offers several contributions to the study of human rights, international norms, and global governance. First, our study offers the most detailed quantitative mapping of politicization patterns in the human rights regime to date. The analytical leverage afforded by our approach allows us to measure the influence of geopolitical interests on enforcement across 54 human rights issues. The granularity of our findings dispels the notion that politicized enforcement maps uniformly onto patterns of geopolitical affinity and hostility. States not only shame their strategic partners quite regularly; they are also more likely to do so on a number of issues, relative to adversaries. Because some human rights issues are more damaging and sensitive than others, governments handle them very differently in the day-to-day practice of world politics.

Second, we introduce a novel theory of politicization that resolves many of the empirical and theoretical puzzles that bedevil conventional wisdom. Notably, the same realists that characterize the human rights regime as hopelessly politicized also tend to dismiss international human rights shaming as politically inconsequential “cheap talk.” The result is a logical puzzle: why bother with selectivity—condemning adversaries while coddling friends—if shaming is inconsequential for the target country? By delineating how states address tensions between politics and norms, particular interests and universal principles, maintaining friendships and reputations for fairness, we resolve this and other puzzles within a unified theoretical framework. Together, our findings have important implications for policy debates surrounding the effectiveness of the international human rights regime. More broadly, a deeper understanding of the strategic logic of shaming opens new avenues for thinking productively about the relationship between norms and power politics in IR theory.

Politicization in the International Human Rights Regime: Received Wisdom and Lingering Puzzles

While human rights are “political” in innumerable ways, we use the term “politicization” to refer to a specific phenomenon: the effect of geopolitical relationships on the likelihood of punishing violations.Footnote 1 We are particularly concerned with politicization within the international human rights regime—that is, the norms and institutions originating in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and subsequent conventions (Donnelly Reference Donnelly1986, 606). Today, a global framework has emerged to define, promote, and monitor human rights, encompassing numerous organizations, multilateral treaties, and mechanisms. And yet, in an inescapably anarchic world, enforcing compliance in this regime largely depends on the discretion of other states (Simmons Reference Simmons2009, chap. 4). The most common tool in this regard is “naming and shaming”—identifying violators, condemning abuses, and urging reform (Franklin Reference Franklin2008; Hafner-Burton Reference Hafner-Burton2008; Lebovic and Voeten Reference Lebovic and Voeten2006). Although some states occasionally consider other tools such as economic sanctions or military intervention, shaming is by far the most common mode of enforcement, practiced by virtually all UN member states since the regime’s inception (Donnelly Reference Donnelly1986, 608).

In our discussion, politicization happens when shaming patterns are influenced by the shamer’s political relationship to the target regardless of the nature of the violating behavior itself (e.g., its severity or credibility). More formally, if X represents the degree of geopolitical affinity between a potential shamer and target and Y equals the likelihood of shaming on a given violation, then the extent of politicization refers to the effect of X on Y, independent of other factors. When this effect is substantial, we characterize the norm as “politicized.” Numerous empirical studies find that politicization, defined as such, is rampant within the human rights regime: states shame violations selectively, harshly condemning their adversaries while going easy on friends and allies for comparable abuses (Donno Reference Donno2010; Lebovic and Voeten Reference Lebovic and Voeten2006; Terman and Voeten Reference Terman and Voeten2018).

Why is the international human rights regime so politicized? The standard explanation follows a realist logic: states enforce some norms some of the time—namely, when they find it in their national interest to do so (Krasner Reference Krasner1999; Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer1994). By this reasoning, leaders have little to gain by enforcing broad adherence to human rights norms in the international system. Unlike domains such as nuclear nonproliferation—where states have a direct stake in the compliance of other countries (Gavin Reference Gavin2015)—leaders rarely have a compelling interest in regulating other governments’ human rights behavior. That is because the main stakeholders of human rights are domestic citizens in the target state, not other countries (Donnelly Reference Donnelly1986, 619; Simmons Reference Simmons2009, 126). Consequently, protecting human rights abroad is typically demoted in favor of other foreign policy goals that are more salient to national interests, such as security or trade. Even if leaders are ideologically inclined to promote human rights, they nonetheless face a persistent free-rider problem, disincentivized to enforce compliance when others are available for the job.

In addition to bearing few direct benefits, enforcing human rights can potentially sabotage important geopolitical relationships.Footnote 2 Human rights encroach on sensitive issues surrounding state legitimacy and sovereignty, and criticism in this area could potentially upset a valuable strategic partner, leading to alienation or retaliation. For example, the United States chose not to sanction Saudi Arabia over the death of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi due to their critical geopartnership. “There isn’t an issue in the Middle East where we don’t need [the Saudis] to play a role,” one veteran official explained, “if you sanction the crown prince directly you basically create a relationship of hostility” (Sanger Reference Sanger2021). Similarly, many Muslim nations stayed silent on China’s abuse of the Uighurs due to fears of “possible retribution” (Perlez Reference Perlez2019). In contrast, states are eager to condemn their geopolitical adversaries as human rights violators. Not only is there no valued relationship to protect in this context, but shamers can potentially benefit from damaging their rivals’ international and domestic legitimacy by casting them as abusers (Lebovic and Voeten Reference Lebovic and Voeten2006, 871–2; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000, 221–2). In effect, when it comes to shaming adversaries, states tell themselves “the more it hurts them, the more it helps me.”

Together, these insights culminate in a straightforward empirical prediction. With few incentives to engage in across-the-board human rights enforcement, states will shy away from condemning strategic partners while eagerly shaming adversaries for the same conduct. Politicization should thus be endemic to the human rights regime—a fixed attribute that maps neatly onto patterns of geopolitical affinity and enmity. Even scholars who are critical of broader realist conclusions on human rights promotion tend to agree with this basic prediction. “If we are looking for emphatic enforcement from other countries,” Beth Simmons writes, “we will be looking in vain for a long time” (Reference Simmons2009, 116).

Despite its intuitive logic, the realist account of politicization nonetheless leads to empirical anomalies and theoretical contradictions. One problem is the prediction that leaders will rarely, if ever, condemn violations perpetrated by geopolitical partners. The fact of the matter is that states do sometimes shame their friends for human rights abuses. Indeed, we show below that states are more likely to shame friends and allies on certain human rights practices, relative to adversaries. This pattern fits uneasily with a frugal realist theory explaining enforcement patterns as a simple function of geopolitical hostility.

The other problem is theoretical. Many of the same scholars who characterize the human rights regime as invariably politicized also underscore its inability to impose meaningful costs on violators. Shaming, in their view, is toothless “cheap talk”: too weak and frivolous to impose a meaningful coercive effect (Krasner Reference Krasner1999; Simmons Reference Simmons2009, chap. 4). It is important to clarify that politicization and toothlessness reflect two distinct problems; the former relates to the distribution of penalties, the latter to the strength of those penalties. Yet many observers lament both in the same breath, such as when US Congresswoman Illeana Ros-Lehtimen characterized the UN Human Rights Council as “a weak voice subject to gross political manipulation” (Gedda Reference Gedda2007).Footnote 3 But if shaming is uniformly irrelevant to its targets, then it is unclear why states should bother discriminating between geopolitical partners and adversaries at all. What exactly do leaders think they are sparing their friends from—and inflicting on their adversaries—if shaming always imposes negligible political costs on the target? The realist conventional wisdom thus underspecifies the mechanisms that drive states to inject their political interests into the human rights arena in the first place.

Overcoming the Dilemma of Shaming

The decision to enforce human rights norms is more complex than a simple realist story would suggest. We argue that states face a thorny dilemma when choosing to punish abuses abroad. On the one hand, governments strive to demonstrate their dedication to the global human rights project, collecting social rewards for promoting human rights in a fair and impartial way. On the other hand, shaming could provoke a negative reaction from the target, potentially undermining a valuable strategic relationship. The solution to this dilemma is to recognize that shaming on some issues is more damaging to the target country than it is on other issues. States pressure allies and adversaries selectively based on how threatening that pressure is perceived to be for the target regime. As a consequence, different norms display different patterns of politicization.

The Problem: Metanorms vs. Geopolitical Interests

Realists are right to be skeptical of international human rights enforcement based solely on the desire to protect human rights abroad. However, compliance is not the only goal states pursue when shaming violations. Governments can accrue other benefits for publicly enforcing norms even if they care little about human rights practices per se. These rewards pertain to “metanorms,” or social pressure to enforce norms by punishing violators. Here, states shame not because they think shaming will deter violations but because they want to signal their commitment to the human rights project and appease third-party audiences.

A large body of research in economics and sociology suggests that metanorms serve a critical role in the reinforcement and continuity of normative orders (Axelrod Reference Axelrod1986; Horne Reference Horne2009). Individuals bear the costs of punishment in order to demonstrate that they themselves subscribe to a given norm and are thus good, reputable, and trustworthy (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Hoffman, Bloom and Rand2016; Posner Reference Posner2000). Like actors on a stage, the shamer is ostensibly speaking to the target, but in reality their performance is directed to an audience who witnesses the display and confers social rewards onto the shamer.

Metanorms provide strong incentives for states to establish a reputation as a principled defender of global human rights. Numerous scholars observe that human rights represent a “new standard of civilization” (Donnelly Reference Donnelly1998) and a “script of modernity” (Krasner Reference Krasner1999, 122) that states must respect if they are to retain domestic and international legitimacy. Governments want to be seen as embracing human rights, even if they harbor no interest in human rights per se (Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005). One primary way leaders can signal such commitments is by shaming other countries for their human rights performance (Horne Reference Horne2009). Criticizing foreign abuses satisfies domestic and international audiences who genuinely believe in the human rights project and wish to see governments promote such principles on the world stage.

Once we consider the social rewards tied to metanorms, it is no longer puzzling why states engage in human rights enforcement even if they may not care about human rights compliance. Unlike a preference for compliance—which arises from the consequences of punishment and benefits the entire group—metanorm rewards follow from the act of punishment itself and benefit only those who perform such acts, making free-riding less tempting. Human rights shaming would be vastly underproduced if not for the incentives generated by metanorms.

Yet, even as states recognize the benefits of paying homage to universal norms, they must also protect their geopolitical interests. Leaders are particularly wary of undermining important strategic relationships on which their security or economic interests depend. Publicly condemning friends and allies can potentially alienate a valued partnership or provoke retaliation. As a result, governments are incentivized to be lenient toward abuses committed by strategic partners (Terman and Voeten Reference Terman and Voeten2018). By the same token, states are eager to defame their adversaries as human rights abusers. Given the baseline relationship of competition and conflict, sanctioning violations among rivals is not only costless for the shamer but also potentially rewarding insofar as it stigmatizes the target.

These conflicting incentives produce a dilemma. On the one hand, metanorms drive states to condemn foreign abuses fairly and consistently, displaying their identity as “good citizens” of the international human rights regime. On the other hand, leaders must secure their geopolitical interests by refraining from offending their partners while inflicting as much damage as possible on adversaries. How do states resolve the tension between metanorm pressures to fairly enforce “universal” human rights norms while at the same time securing their narrow geopolitical interests?

The Solution: Variations in Sensitivity

We argue that states navigate the shaming dilemma by selectively shaming human rights violations based on how “sensitive” they are for the target state. We start from the premise, contra skeptics, that shaming can impose some costs onto target states and thus affect their behavior (Barry, Chad Clay, and Flynn Reference Barry, Clay and Flynn2012; Hendrix and Wong Reference Hendrix and Wong2013; Krain Reference Krain2012; Lebovic and Voeten Reference Lebovic and Voeten2009; Murdie and Davis Reference Murdie and Davis2012). Importantly, we also propose that such costs vary across different types of violations. While human rights are commonly described as “indivisible, interrelated, and interdependent,” the reality is that some norms are more threatening than others are because they directly challenge the power or legitimacy of the ruling regime. Shaming on these issues is more damaging for the target state and therefore provokes greater resistance and opposition.

Researchers of human rights and democracy promotion commonly invoke the idea of “sensitive” issues or cognate concepts reflecting a similar intuition. In her study of international democracy assistance, for example, Sarah Bush defines “regime-compatible” programs as those that “target-country leaders view as unlikely to threaten their imminent survival by causing regime collapse or overthrow” (Reference Bush2015, 60). In contrast, “regime-incompatible” programs are those that endanger the political livelihoods of incumbents by fostering political competition and dissent. Bush’s conceptualization allows her to distinguish between various democracy-promotion programs and their likely reception by target governments (Reference Bush2015, 68–72). Insofar as democracy organizations advocate for regime-incompatible issues, they face greater opposition and barriers to access. A similar logic holds for human rights shaming. From the perspective of leaders in the target country, some accusations are more damaging to the regime’s legitimacy, power, and/or control. We refer to these issues as “sensitive” because they generate stronger defensiveness and negative reactions from target countries. “Safer” issues are those that are perceived as less threatening and thus more tolerable to authorities.

Broadly speaking, human rights shaming varies in sensitivity for two analytically distinct (but frequently overlapping) reasons. First, shaming is highly sensitive when it accuses the target regime of highly stigmatized, “gross” human rights violations that tarnish the regime’s legitimacy and reputation. In their canonical study of transnational advocacy networks, Keck and Sikkink observe that “issues involving bodily harm to vulnerable individuals” with “a short and clear causal chain” of responsibility appear particularly reprehensible to global publics, generating widespread moral outrage and condemnation (Reference Keck and Sikkink1998, 27). Torture, disappearances, and other “physical integrity” violations provide the clearest examples: they typically involve grievous bodily harm while directly implicating state authorities as willful abusers. Because it is widely accepted that legitimate governments respect these rights at minimum, being shamed on physical integrity violations is more embarrassing and reputationally costly compared with other issues. For targeted regimes, such accusations risk sabotaging both international benefits such as foreign aid (Esarey and DeMeritt Reference Esarey and Jacqueline2017; Lebovic and Voeten Reference Lebovic and Voeten2009) and domestic legitimacy and support (Krain Reference Krain2012).

Second, shaming is highly sensitive when it involves norms that are costly to comply with, typically for domestic political reasons. For example, scholarly consensus holds that incumbent regimes view open competition and dissent as threatening to their political survival, motivating repressive measures (Davenport Reference Davenport2007; Ritter and Conrad Reference Ritter and Conrad2016). Civil-political rights such as free speech, free assembly, and political participation could endanger incumbents by fostering political competition or mobilizing independent groups that are likely to challenge those in power (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2016; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Snyder and Ballentine Reference Snyder and Ballentine1996).Footnote 4

Migrant rights also typify norms that carry high compliance costs. International migration has become a source of increasing stress for governments, particularly in advanced economies. As Jeff Colgan and Robert Keohane argue, “almost everyone agrees that there is some limit to how rapidly a country can absorb immigrants,” which presents political leaders with “tough decisions about how fast people can come in and how many resources should be devoted to their integration” (Reference Carraro2017, 44). Meanwhile, as the recent migrant crisis grows more volatile and rich countries strain under burgeoning anti-immigrant sentiments, the domestic political risks surrounding migrants’ rights have become a major liability for many governments. Protecting migrant rights thus implies significant political as well as financial costs for these governments.

Other types of human rights enforcement are considered relatively safe by target states for corresponding reasons. Criticisms involving socioeconomic rights are especially nonthreatening to the target state’s legitimacy and reputation. Historically, failure to secure access to health or education has attracted less moral outrage compared with physical integrity violations, as authorities can easily displace responsibility onto exigent circumstances such as poverty and underdevelopment. As recognized by the executive director of Human Rights Watch, economic and social rights violations “naturally [reduce] the potential to stigmatize any single actor” (Roth Reference Roth2004, 68).

Socioeconomic rights also pose little threat to target regimes’ domestic political interests, at least in the short term. Unlike civil-political liberties that constrain the state, these “positive” rights require an active and expansive role from government authorities, who are often happy to oblige. Most regimes hold a vested interest in improving conditions related to public health, poverty, education, and natural resources. In China, for example, Jessica Teets documents how government officials not only allow but actively cooperate with nongovernmental organizations working on such issues. Far from being costly, embracing such norms aligns with the ruling regime’s interest in meeting development goals and ensuring “social stability” (Reference Teets2014, 65).

Women’s and children’s rights likewise exemplify the core qualities of safe norms. Historically, much of the international women’s rights movement has foregrounded abuses committed by private citizens, such as domestic violence or sex trafficking (Bunch Reference Bunch1990). Unlike physical integrity rights, social problems like domestic violence and trafficking do not involve abuses committed by state actors and are therefore less likely to damage the legitimacy of ruling regimes. In addition, women’s and children’s rights rarely threaten the survival of incumbents (Ottaway Reference Ottaway, Carothers and Ottaway2005). On the contrary, they provide authorities with a means to demonstrate their compassion for weak and vulnerable populations, extend their reach into private life (e.g., increased policing), or bolster their reformist credentials. Of course, some countries like Saudi Arabia or Iran are routinely condemned for state-sponsored discrimination against women. However, as we detail in later sections, even these regimes see women’s rights as relatively unthreatening insofar as they can fold such reforms under the monitoring and control of “state feminism.”Footnote 5 While feminist movements may challenge hegemonic masculinity undergirding state power in the long term (Hooper Reference Hooper2001), contemporary discourses on women’s and children’s rights are quite compatible with, and often entrench, existing power structures.Footnote 6

Our conceptualization of “sensitive” and “safe” human rights enforcement is far from indisputable. Although we rely heavily on existing theory and empirical findings, some designations are clearer cut than are others. Later, we validate our descriptive inferences through statistical analysis, bolstering our confidence in their conceptual robustness. However, we acknowledge the possibility that some norms that we regard as generally safe, such as women’s rights or socioeconomic rights, can be deeply threatening to target regimes in particular cases. Ultimately, our claim is a general and relativist one: overall, shaming on certain human rights issues is more damaging, relative to other issues. These variations matter, both for the likely reception of foreign shaming from target governments and the decision to shame violations in the first place.

Empirical Implications

Once we recognize that certain kinds of criticism are more sensitive than others, it stands to reason that states can overcome the shaming dilemma by exploiting the variant sensitivities of different human rights norms. Just as scholars undergoing peer review would much rather have their manuscripts critiqued for typographical mistakes than for plagiarism, countries reviewed on their human rights performance typically prefer to be shamed on safer issues over those that are more damaging. Recognizing this preference among their peers, shaming states will shy away from sensitive issues when criticizing geopolitical friends and allies. Instead, they will gravitate toward safer topics such as those involving socioeconomic development or the protection of women and children. This strategy allows shaming states to present themselves as genuine defenders of global human rights while at the same time safeguarding valued strategic partnerships from awkward confrontation.

The calculus is inverted when addressing geopolitical adversaries. Here governments benefit from inflicting maximum political damage onto the target’s domestic legitimacy or international reputation. Therefore, they are more likely to punish adversaries on highly sensitive issues, including violations associated with physical integrity, freedom of speech and expression, and political participation. By applying such pressure, shaming states can collect metanorm rewards from third-party audiences while potentially defaming the target as an egregious human rights violator.

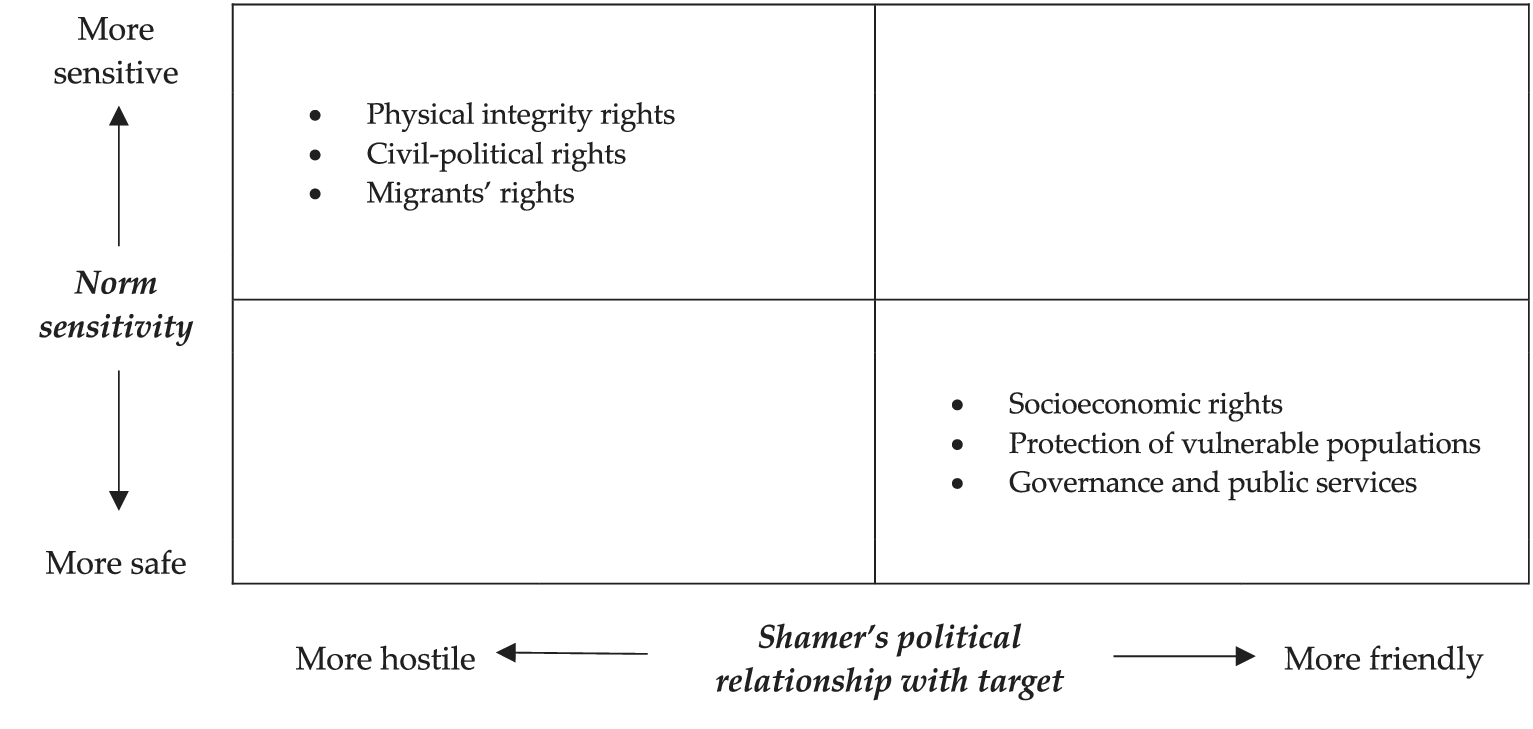

Together, these insights produce an intriguing empirical implication: not only should we see politicization in the human rights regime overall, but politicization patterns should vary across different issues. As visualized in Figure 1, the effect of geopolitical relations on human rights criticism is conditional on how politically sensitive that criticism is to the target state, all else equal. Shaming on sensitive issues is more likely to occur when the shamer and target are adversaries. Shaming on safer issues is more common when the shamer and target share a strategic partnership. Note how this contrasts with the conventional wisdom wherein states are simply expected to shame their adversaries and coddle friends. In our theory, states not only shame friends regularly but also are more likely to enforce certain norms (i.e., those that are relatively safe) when the violator is a strategic partner.

Figure 1. Predicted Relationship between Politicized Enforcement and Sensitivity

The Universal Periodic Review

We test the argument using newly available data from the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), a process conducted by the United Nations Human Rights Council wherein states “peer review” one another’s human rights records.Footnote 7 Reviews take place through an interactive dialogue between the state under review (SuR) and all other UN members (and permanent observers Palestine and the Holy See). First, the SuR presents a self-assessment of its human rights practices. All other states then have the opportunity to provide feedback in the form of specific recommendations. Each UN member can issue zero, one, or more recommendations per review. The SuR must then publicly decide whether to support or reject each recommendation it receives. Once complete, an outcome report of the review is compiled, and the SuR has 4.5 years to implement the recommendations it supported before undergoing another review in the next cycle.

The UPR presents an ideal empirical laboratory for examining patterns of punishment and politicization in the human rights regime. While delegations are mandated to be objective in their reviews, the reality is that state representatives have broad leeway in what they choose to address and how. As a result, recommendations vary widely in both content and tone—spanning the spectrum of potential human rights concerns—even when directed to the same country. Some admonish the SuR in scathing terms, representing shaming par excellence. Others resemble relatively gentle (if banal) commentary or even praise the SuR for improved conduct.

Cuba’s experience in the UPR illustrates these variations. During its 2013 review, North Korea urged Cuba to “[p]romote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among the peoples of the world” and “continue with its positive efforts.” In contrast, the United States lambasted Cuba’s repression of political dissidents and journalists and demanded that it “[e]liminate or cease enforcing laws impeding freedom of expression” (United Nations General Assembly 2013a). Cuba, for its part, has used the UPR to accuse the United States of genocide, war crimes, and the repression of African Americans and indigenous peoples (United Nations General Assembly 2011).

We take advantage of the UPR’s natural variation in review content to examine the politicization patterns of different norms. Regardless of valence, all UPR recommendations promote specific norms, providing useful information on the reviewer’s normative concerns vis-à-vis the target state. For example, some recommendations might condemn the SuR for violating women’s rights while others commend it for improved practices. In all instances, however, the reviewing state is reaffirming women’s rights as a matter of legitimate concern for the target state. Thus, by examining how patterns of geopolitical affinity condition the kinds of norms states choose to address in the UPR, and how they choose to address them, we can observe our hypothesized enforcement dynamics at work.

We analyze data compiled by UPR Info, a nonprofit organization monitoring the process (UPR Info 2015).Footnote 8 The sample includes all recommendations made during the first two cycles of the UPR working group (n = 57,867). During this time, 193 countries were each reviewed twice, once per cycle. For each recommendation, data were collected on the state offering the recommendation (the Reviewer), the SuR receiving the recommendation (the Target), and the SuR’s response to the recommendation (the Response). UPR Info researchers also hand labeled each recommendation according to the kind of action demanded on the part of the SuR (Severity), and the specific Issue(s) involved, from a set of 54 nonmutually exclusive categories (e.g., “Women’s Rights,” “Detention,” “International Instruments”).Footnote 9 Table 1 provides sample observations.

Table 1. Examples of UPR Recommendations

Identifying Politicized Issues

We argue that the effect of geopolitical relations on peer review varies across different human rights issues. To test this claim, we transformed the UPR data into a directed dyadic structure. The sample consists of all dyads between states undergoing a review in a given year and states that offered at least one recommendation in that review, totaling 20,130 observations. Among those states that did participate as reviewers, delegations offered an average of 2.8 recommendations per review.

We estimate 54 models, one for each of the 54 issue categories. For each model, the dependent variable records the count of recommendations addressing a particular issue offered by a given reviewer. The main explanatory variable is the degree of geopolitical affinity between reviewer and target. We measure Geopolitical Affinity by taking the absolute distance between country ideal-points that are estimated by using votes in the United Nations General Assembly and multiplying this distance by minus one (Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017).Footnote 10 Higher numbers indicate greater levels of affinity between the reviewer and target, and lower numbers indicate more hostility.

We also consider several potentially confounding variables that could affect the likelihood of criticism. One straightforward possibility holds that the number of recommendations about any given issue is proportional to the number of total recommendations offered by a given reviewer. France may issue numerous recommendations to the United States about the death penalty because France offered many recommendations to the United States in general. To account for this possibility, we control for the total number of recommendations issued by a given state during a review.

Second, we control for the mean level of severity in recommendation(s) exchanged in a given dyad.Footnote 11 UPR Info coded each recommendation based on the first verb and the overall action contained in the recommendation. Following Terman and Voeten (Reference Terman and Voeten2018), we transformed these action codes into a three-point ordinal measure of recommendation Severity, with higher levels denoting severe or demanding recommendations.Footnote 12

Another potential confound involves the tendency for norm-abiding states to shame norm-violating states in harsher terms. Given that some of the hypothesized explanatory variables are plausibly correlated with human rights records, we include a measure of physical integrity rights protections for both reviewer and target (Fariss Reference Fariss2014).Footnote 13 The models lag time-variant relational variables by one year to mitigate simultaneity issues and reduce any incorrect direction of inference.

We also include an indicator for whether the reviewing country was undergoing a review during the same session as the target. Reviewing states who themselves undergo a UPR in the same session may wish to be seen as participating, but they might shy away from politically sensitive commentary due to expectations of reciprocity.Footnote 14 In addition, many observers note that coregionals face more pressure to deal tactfully with one another. Shared region is strongly correlated with UN voting patterns and may thus confound relationships between our variables of interest. Therefore, the models control for whether the target and reviewer countries come from the same region using classifications from the Correlates of War (COW) project.

Finally, there are likely unobserved characteristics of reviewer and target states that affect their propensity to send and receive recommendations. The models include fixed reviewer and target country effects, which control for unobserved and stable state characteristics. They also include fixed effects for the year in which the UPR review took place in order to account for possible learning effects or unobserved contextual factors. We report results from ordinary least squares (OLS) models for ease of interpretation, though we replicate the analysis using zero-inflated Poisson and hurdle count models in Appendix 7.

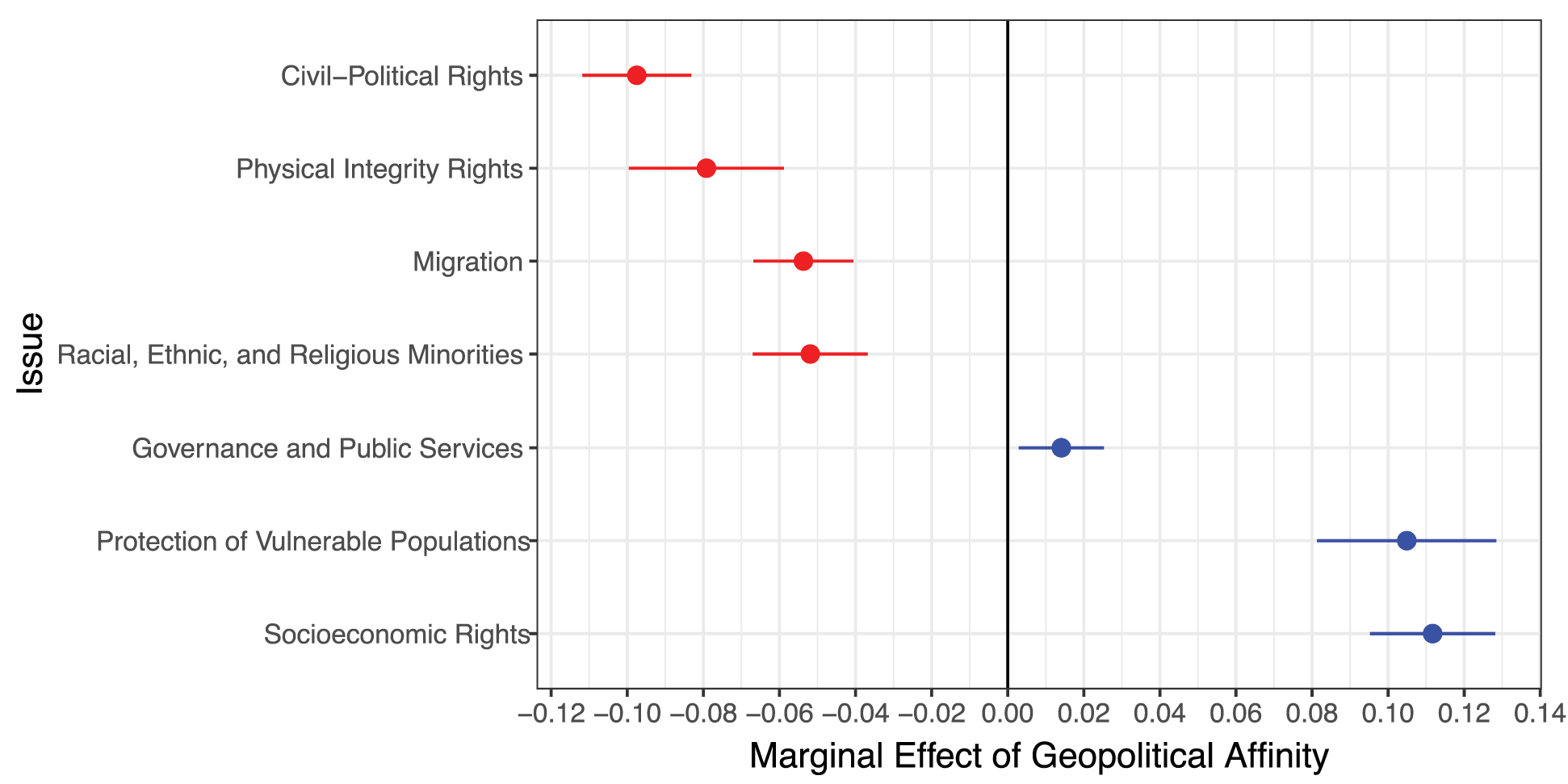

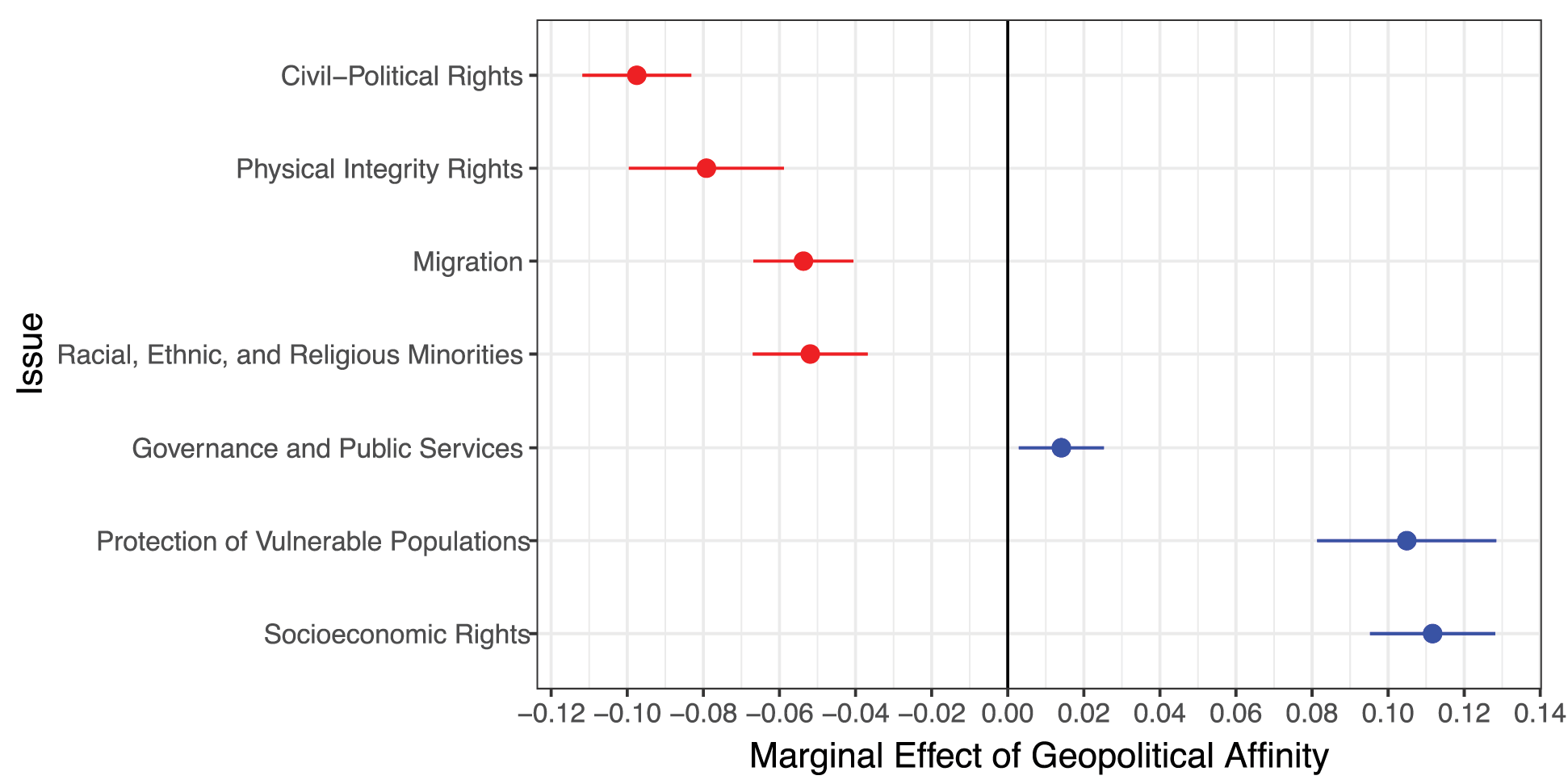

Figure 2 reports the marginal effect of Geopolitical Affinity on the number of recommendations offered by a given reviewer in each issue category, controlling for other factors. To summarize these findings, we grouped the 54 individual issues into seven thematic clusters: (1) civil-political rights; (2) governance and public services; (3) migration; (4) physical integrity rights; (5) racial, ethnic, and religious minorities; (6) socioeconomic rights; and (7) protection of vulnerable populations.Footnote 15 We then repeated the statistical procedure described above on each cluster (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Effect of Geopolitical Affinity on Recommendation Counts, by Issue

Note: The x-axis denotes the marginal effect of Geopolitical Affinity on the number of recommendations offered by a given reviewer for each issue category, controlling for other factors. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Issues are ordered top to bottom by corresponding point estimates on the x-axis. Colors indicate sign and significance of the effect of Geopolitical Affinity on number of recommendations.

Figure 3. Effect of Geopolitical Affinity on Recommendation Counts, by Theme

Note: The x-axis denotes the marginal effect of Geopolitical Affinity on the number of recommendations offered by a given reviewer for each thematic category, controlling for other factors. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Issues are ordered top to bottom by corresponding point estimates on the x-axis. Colors indicate sign and significance of the effect of Geopolitical Affinity on number of recommendations.

Overall, we find that states moderate their criticism of human rights conditions depending on their geopolitical relationship with the target. When evaluating a strategic partner, representatives tend to avoid highly sensitive human rights issues in favor of topics that register as safer and less threatening to target regimes. Meanwhile, reviewers reserve their most stigmatizing commentary for their geopolitical rivals, whom they push particularly sensitive or politically damaging human rights issues.

Specifically, higher levels of Geopolitical Affinity are associated with safer topics such as socioeconomic rights (e.g., right to education, right to health) and the protection of vulnerable populations (e.g., women’s rights, rights of the child, trafficking). These substantive domains typically involve abuses that take place in the private sphere, absolving state actors as the perpetrators of human rights abuse while envisioning their role as protectors and providers. Such rights not only pose low risks to regime survival but also may enhance regime power by legitimating state expansion and capacity. By gravitating toward safer issues, shaming states can claim they are promoting human rights by participating in the UPR—thus satisfying metanorm pressures—while simultaneously protecting their geopolitical relationships from damaging confrontation.

In contrast, lower levels of Geopolitical Affinity (i.e., greater hostility) are associated with more politically sensitive issues, such as those concerning civil-political liberties (e.g., freedom of opinion and expression, elections) and physical integrity violations (e.g., torture, human rights violations by state agents). These issues tend to be more threatening to target countries because they attribute abuse to state actors (e.g., torture, impunity), promote open political competition and dissent (e.g., freedom of opinion and expression, elections), and/or impose demanding constraints on domestic rule (e.g., migration—including citizenship and refugee issues).

Substantively, conditional on participating in a review, a one-point (one standard deviation) increase in Geopolitical Affinity is associated with 0.047 more recommendations about the right to education but 0.06 fewer recommendations on freedom of opinion and expression. Although these effects appear to be small, note that they indicate changes relative to a modest baseline. The average number of recommendations addressing freedom of opinion and expression across all reviewers is only about 0.083 per review. A change of 0.06 is therefore quite substantial; it nearly nullifies (in one direction) or doubles (in the other direction) the average amount of criticism in this area.Footnote 16

Our findings both affirm and expand on those of Terman and Voeten (Reference Terman and Voeten2018), who find that states are more lenient toward strategic partners in the UPR (though any criticism they do offer is more likely to be accepted by the target state). More specifically, holding constant the specific issue involved, recommendations exchanged between geopolitical partners were found to be less severe on average (i.e., with lower Severity ratings). Our findings extend this basic intuition by observing systematic patterns in the substantive topics reviewers choose to address. Not only are states more lenient with friends; they also focus on safer and less threatening content. Meanwhile states tend to shame their rivals both on particularly sensitive issues and in a more demanding fashion.

These patterns hold across a number of specifications (Appendix 7). First, we examine potential selection bias resulting from voluntary participation. In our data, participation is identical for states qua targets (each country was reviewed twice) but highly uneven for states qua reviewers. While all UN states are invited to offer feedback in every review, they are not forced to do so. A potential reviewer offered at least one recommendation in 27% of the cases.Footnote 17

We examine potential selection bias in two ways. First, we replicate the analysis on a larger sample including all dyads between an SuR and a potential reviewer (i.e., all UN member states) using zero-inflated count models. Second, we exploit membership on the Human Rights Council (HRC) as a plausible instrument for participation. Only comments presented orally during UPR working group sessions are entered into the record. When states sit on the HRC, they typically have human rights delegations in Geneva that are expected to participate in sessions. Thus, HRC members are much more likely to participate in the UPR overall, but there is little reason to expect HRC members to issue more or less politicized recommendations, all else being equal. We replicate the analysis on a subsample of reviewing states sitting on the HRC during the time of the review, finding that our primary results remain consistent.

In addition, because some reviews focus more on praising improved practices than shaming violations, we repeated the analysis on a subsample of the most critical recommendations (i.e., those with Severity level 3).Footnote 18 We also estimated models with an alternative measure of Geopolitical Affinity using formal alliances. Finally, we employ hurdle count models to lend further insight into the effect of Geopolitical Affinity on recommendations counts. The overall results are consistent with our main findings.Footnote 19

Identifying Sensitive Issues

In our theory, geopolitical relations influence human rights enforcement insofar as some issues are more politically sensitive than others are. In the previous section, we observed that states were more likely to evaluate their friends on certain dimensions (e.g., women’s rights) while confronting their adversaries on others (e.g., migrants). But how do we know these discrepancies are driven by variation in sensitivity? In other words, is migration really more politically sensitive than women’s rights? Earlier, we applied existing research and substantive knowledge to assess how shaming in these domains is likely to be interpreted by target governments. In this section, we corroborate these intuitions through additional analysis of UPR interactions—namely on target Response.

Unlike the previous analysis, which examined reviewer behavior, the following analysis explores the behavior of the target. The goal is to ascertain which human rights issues are more or less tolerable for states, thereby approximating a measure of sensitivity. To do so, we exploit the fact that the SuR must publicly declare whether or not it supports each recommendation received during a given review. Target support offers a helpful, if imperfect, proxy for recommendation sensitivity. In institutional terms, supporting a recommendation forces the SuR to follow up on that item during its next review. In theoretical terms, supporting a recommendation involves a public commitment that may entrap governments in their own rhetoric, leaving them vulnerable to normative pressure from transnational and domestic advocacy groups (Ropp, Sikkink, and Risse Reference Ropp, Sikkink and Risse1999; Simmons Reference Simmons2009). As a result, states are less likely to support a recommendation if it threatens their political control or imposes other prohibitive costs.

In the following analysis, the unit of observation is an individual recommendation (n = 57,867). The dependent variable is a dichotomous Response variable indicating whether the target state supported the recommendation. We expect that countries are more or less likely to support recommendations based on the issue entailed. Therefore, we include all 54 Issue categories as dummy variables in the model. We also control for the recommendation’s Severity, described above. Not surprisingly, states are more likely to support recommendations that involve vague or congratulatory language over those involving specific demands.

We also include several controls pertaining to the relationship between reviewer and target. Critically, the model controls for Geopolitical Affinity between reviewer and target, as strategic ties affect both the content and reaction to recommendations.Footnote 20 We also control for the shamer and target’s physical integrity rights protections and shared region. Again, we include fixed effects for reviewer, target, and year. Although all results are robust to a logit estimation, we report estimates from an OLS model in order to facilitate interpretation.

Figure 4 plots the marginal effects of each Issue category on the likelihood of target support, controlling for other factors (including Geopolitical Affinity). Figure 5 repeats the analysis by grouping individual issues into thematic clusters. Of all recommendations, 73% were eventually supported, but we observe wide variation by issue. Notably, recommendations addressing the death penalty are more than 36 percentage points less likely to be supported, all else being equal. In contrast, recommendations addressing disabilities are more amenable, all else being equal. Indeed, 89% of the recommendations concerning disabilities were eventually supported by the state under review. In contrast, only 22% of the recommendations concerning the death penalty were supported.

Figure 4. Effects of Issue on Probability of Recommendation Support

Note: The x-axis denotes the marginal effect of recommendation issue on the likelihood of target support, controlling for other factors. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Issues are ordered top to bottom by corresponding point estimates on the x-axis. Colors indicate sign and significance of the effect of recommendation issue on the likelihood of target support.

Figure 5. Effects of Issue Theme on Probability of Recommendation Support

Note: The x-axis denotes the marginal effect of recommendation theme on the likelihood of target support, controlling for other factors. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Issues are ordered top to bottom by corresponding point estimates on the x-axis. Colors indicate sign and significance of the effect of recommendation issue on the likelihood of target support.

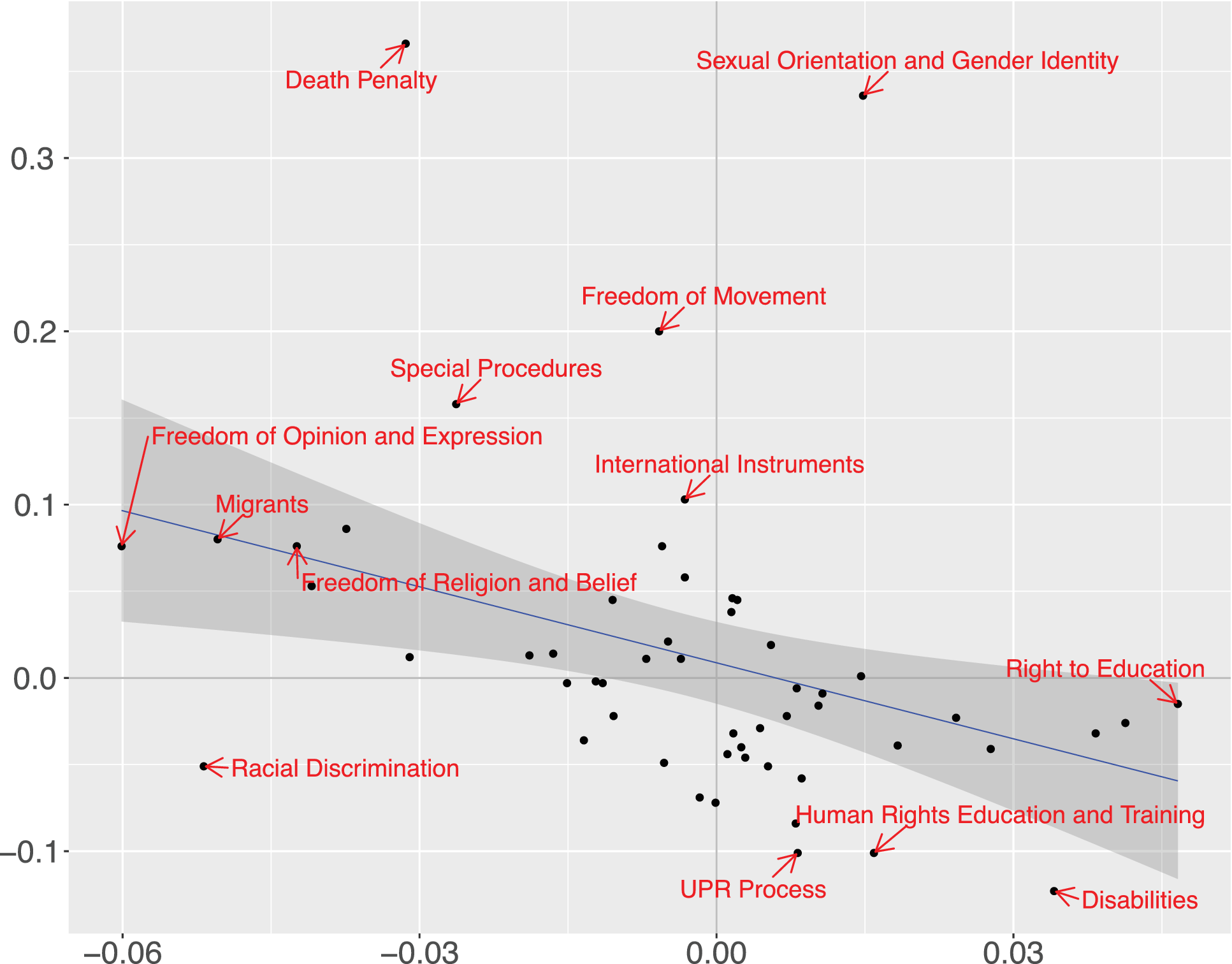

Importantly, issues that are most likely to be scrutinized by a geopolitical adversary are also the least amenable to the target state. To demonstrate this pattern, Figure 6 shows the correlation between politicization and sensitivity in human rights shaming (Pearson’s correlation = 0.36, p = 0.006).Footnote 21 The plot maps each of the 54 issues onto two dimensions. The x-axis captures the degree of politicization—that is, the effect of Geopolitical Affinity on a reviewer’s tendency to shame the target on a given issue—using coefficient values reported in Figure 2. The y-axis captures the degree of sensitivity—that is, the likelihood a target state will support or reject a recommendation addressing that issue regardless of who sent it—using coefficient values reported in Figure 4 (sign reversed).Footnote 22 The figure provides the clearest evidence of our primary claims: states enforce sensitive issues against their adversaries and safer issues against their friends.

Figure 6. The Relationship between Politicization and Sensitivity

Note: The x-axis captures the degree of politicization using model coefficients reported in Figure 2. The y-axis captures the degree of sensitivity, using the model coefficients reported in Figure 4 (sign reversed). The shaded line indicates the 95% confidence level of the fitted linear relationship.

Specifically, recommendations involving civil-political rights, physical integrity rights, and migrants’ rights are both more common between geopolitical adversaries and highly sensitive to target states. Meanwhile, recommendations exchanged between geopolitical friends tend to address topics that are independently amenable to target governments, such as socioeconomic rights and protection of vulnerable groups. Regarding institutional governance, states tend to demand that their rivals submit to strong international mechanisms (i.e., special procedures) while allowing their friends to retain domestic control through national plans of action, national human rights institutions, and human rights education.

While the results generally match our predictions, we find two exceptions to the overall trend: (1) Racial Discrimination, which is more likely to be addressed by states against their adversaries but also more likely to be supported by the target, and (2) Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, which is more likely to be directed at allies but less likely to be supported by the target. Also notable is the Death Penalty, which falls in direction predicted by the theory but is anomalous in magnitude. These exceptions provide intriguing avenues for further research. Nonetheless, they should not raise serious doubts about our main theoretical claims, which are probabilistic and not determinative in nature. Indeed, we should expect some topics to fall “off the diagonal” due to local dynamics or circumstances that fall outside the scope of our theory. For example, some leaders may hold strong preferences regarding behavioral compliance with a particular norm (e.g., sexual orientation and gender identity). If such preferences are sufficiently strong, countries may be compelled to shame their allies despite the geopolitical risks.Footnote 23

These caveats notwithstanding, the overall pattern is clear: variation in the politicization of human rights largely maps onto variation in their attendant sensitivity for the target. States spare their strategic allies in the review process, avoiding sensitive topics while providing safe and easily digestible recommendations. Adversaries, on the other hand, tend to confront one another in particularly offensive ways, on precisely the kinds of issues that register as sensitive and evoke defensiveness.

Illustration

Canada’s reviews of Iran and Saudi Arabia provide a useful illustration of these dynamics. Canada issued five recommendations to Iran during its 2014 review, highlighting sensitive issues such as freedom of speech, the death penalty, and abusive detention conditions. At times, Canada’s recommendations explicitly demanded punishment for Iranian state actors or the rollback of their authority. For example, it urged that Iran “[i]nvestigate and prosecute all those responsible for the mistreatment or abuse of detained prisoners” (United Nations General Assembly 2015, 23) and “[a]mend its press law to define the exceptions to article 24 of its Constitution in specific terms and that do not infringe upon freedom of expression” (United Nations General Assembly 2015, 24).

By contrast, Canada’s recommendations to Saudi Arabia during the same cycle highlighted the plight of vulnerable groups such as women, children, and religious minorities. Canada also refrained from directly incriminating the Saudi government. Instead, its recommendations were noticeably indeterminate, such as when it urged “necessary measures to ensure the effective enjoyment and protection of the right to freedom of religious belief, with a view to promoting the equality of all peoples and respect for all faiths,” a recommendation Saudi Arabia supported (United Nations General Assembly 2013b, 17).

It is difficult to ascribe these contrasts to differences in Iran and Saudi Arabia’s human rights records. Although Canada criticizes Iran more than Saudi Arabia for violations of civil and political rights, widely used human rights metrics tend to evaluate the former more favorably than the latter.Footnote 24 Canada’s discriminating approach is better explained by its cooperative relationship with Saudi Arabia and adversarial relationship with Iran. Saudi Arabia not only cooperates with Canada on important issues such as counterterrorism and refugees; it is also Canada’s second-largest foreign supplier of oil (Kaplan, Milke, and Belzile Reference Kaplan, Milke and Belzile2020). By contrast, as a member of NATO and a close ally of the United States, Canada has long been hostile to the Iranian regime, going so far as to sever formal diplomatic relations in 2012.

For the Saudi regime, criticisms on issues like women’s rights and social freedoms are relatively easy to embrace, especially compared with overtly political demands like free speech. In fact, shortly after assuming the throne, crown prince Mohammad bin Salman eagerly implemented such reforms as cracking down on corruption and lifting the ban on women driving, for which he was lauded as a modernizer and revolutionary by Western pundits (Friedman Reference Friedman2017; O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2018). Meanwhile, experts warned that such changes amounted to little more than a “smokescreen” and “women-washing” palliating a repressive regime (Bayoumi Reference Bayoumi2018; Mahdawi Reference Mahdawi2018). Even as the monarchy co-opted the rhetoric of women’s rights under the control of state feminism, it arrested independent feminist activists, along with journalists, intellectuals, and others posing a political challenge. Furthermore, allowing women to drive was widely viewed as a strategic move to bolster the Saudi economy by bringing women in the workforce (Hvidt Reference Hvidt2018). “The crown prince offers limited advancements in women’s rights,” writes Nermin Allam, “to appeal to the Western audience and to consolidate his power amid a shifting economic and political landscape” (Reference Allam2019).

Given this situation, it is not surprising that Western allies, including Canada and the United States, appear unafraid to pressure Saudi Arabia on women’s rights issues, in both public venues such as the UPR and bilateral diplomatic settings. Not only do such demands fail to pose a serious democratic challenge to the monarchy; they are welcomed as a means to project a reformist image, attract foreign business to a struggling economy, and distract from more sensitive issues such as domestic repression and brutality in Yemen. By focusing on safer issues, Western states can appear as though they are holding their allies accountable while simultaneously shielding important geopolitical interests from genuine confrontation.

It is also worth noting how Syria’s approach in the same UPR cycle reverses these patterns. Syria admonished the Saudi government for “preventing Syrian pilgrims from practicing their religious duties as it constitutes a flagrant violation of freedom of belief and religion” (United Nations General Assembly 2013b, 24). Meanwhile, it encouraged Iran to “[c]ontinue efforts to highlight the negative repercussions of both terrorism and unilateral coercive measures [imposed by the United States] on national development plans and on the enjoyment of basic human rights by its citizens” (United Nations General Assembly 2015, 14). Again, these differences are attributable to geopolitical relations: Syria’s relationship with Saudi Arabia has long been strained due to bitter regional disputes, whereas it has often cooperated with Iran on an array of important interests.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to systematically map politicization in the international human rights regime using quantitative analysis. We observe that different human rights issues display different politicization patterns. Rights that are perceived as especially threatening to target regimes—such as free expression, physical integrity, and migration—are wielded by states to tarnish their geopolitical rivals. In contrast, safer issues—including education, women’s rights, and trafficking—are enforced more often between geopolitical friends and allies. In explaining this variation, we substantiate an intuition that is widely invoked but rarely explicitly theorized: that some human rights issues are more sensitive than others, with governments handling them differently on both the giving and receiving ends of international enforcement.

In addition to our substantive findings, we advance the theoretical literature by presenting a novel theory of politicized enforcement. Our theory overcomes several empirical and theoretical challenges vexing the conventional wisdom. For one, standard realist logic has difficulty explaining why states shame friends at all. We provide an answer by emphasizing metanorms: even if leaders care little about human rights compliance per se, they can still benefit from publicly enforcing norms in a way that appears fair and impartial, leading them to criticize friends.

In addition, many scholars dismiss human rights shaming as simultaneously politicized and toothless, engendering a paradox: states supposedly go to great lengths to protect their friends from—and inflict their enemies with—something that is politically inconsequential. We argue that shaming can, in fact, inflict considerable damage on target regimes. Importantly, however, some kinds of human rights pressure are more damaging than others. When states view certain criticisms as particularly embarrassing or threatening to the target state, they are less likely to impose those criticisms on their geopolitical friends and more likely to impose them on adversaries. Thus, human rights shaming becomes politicized by virtue of its normative ability to impose costs on target regimes.

Our findings have a number of implications for important theories on shaming, human rights, and international norms. First, our research adds to the literature on shaming in world politics by elaborating its strategic logic as well as the importance of metanorms. Despite its reputation as a tool to deter abuse, shaming is not always designed to secure compliance with global norms. Rather, leaders shame as a way to bolster their own reputation as “good citizens” of the international community. One implication is that it is rational for leaders to shame even if their efforts fail to change the target’s behavior or result in backlash.

This research also has implications for work on human rights. While our investigation brackets the target government’s initial decision to violate human rights—instead focusing on international reactions to apparent violations—potential violators may very well anticipate this politicized enforcement and adjust their human rights behavior accordingly. Previous research suggests that target governments treat shaming from their geopolitical partners more seriously while brushing off criticism from adversaries (Carraro Reference Carraro2017; Terman and Voeten Reference Terman and Voeten2018). We provide the additional insight that shaming states are reluctant to punish their geopolitical partners on sensitive norm violations. As a result, are governments paradoxically emboldened to engage in violations that are perceived as more sensitive? If so, this implication would directly challenge the hypothesis that states strategically substitute highly sensitive violations (i.e., those attracting significant international pressure) with those that are less sensitive or harder to monitor.Footnote 25 Future research is needed to untangle the complex strategic interactions involving human rights practices and politicized enforcement; formal modeling will be especially useful in this respect.

Our conceptualizations of politicization, metanorms, and sensitivity provide new analytic tools to understand normative change. In particular, politicized enforcement has important consequences for the legitimacy of international norms and institutions. Highly sensitive norms, such as the prohibition of genocide or war crimes, may come to be associated with geopolitical conflict insofar as they are enforced more frequently between international rivals. When governments are shamed by their adversaries, domestic audiences and other observers may plausibly assume that it was motivated by cynical intentions—a reflection of political bias and hostility rather than an impartial application of universal principles. If so, patterns of biased enforcement may provide rhetorical resources for leaders wanting to discredit all criticism about a given issue, even those enacted by well-meaning, impartial actors (Gruffydd-Jones Reference Gruffydd-Jones2019). This insight could help explain recent crises of legitimacy faced by international courts and other institutions (Voeten Reference Voeten2020). Inversely, norms enforced mainly between political allies—such as women’s rights or rights to education—may have their legitimacy diminished insofar as they are appropriated by existing powers to bolster control.

More broadly, this research addresses a core issue in international relations theory: the relationship between norms and power politics in global governance. A burgeoning literature highlights the ways in which states use and manipulate international norms (as well as laws, rules, and organizations) instrumentally in pursuit of their strategic interests (Bob Reference Bob2019; Búzás Reference Búzás2018; Dixon Reference Dixon2017; Hurd Reference Hurd2017; Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2001). While this literature offers an important corrective to the liberal-constructivist approach to norms as an antidote to naked power, it has also been criticized for evacuating norms of any independent substantive content or regulatory purchase that might resist appropriation. In doing so, it ultimately risks conceding to the realist account of international institutions as nothing more than power politics in disguise (Peters Reference Peters2018). Our theory occupies a middle ground, emphasizing both the causal powers of norms (i.e., their substantive content) and their use and manipulation in the service of state interests. The politicization of international institutions is a consequence of political and normative logics that motivate states to respect the rules while protecting their geopolitical interests. It is by virtue of their normative powers that international institutions are subject to political manipulation. Acknowledging this mutual reliance invites us to reexamine the link between norms and politics in the international order.

Last, our findings offer important lessons for policy debates surrounding the effectiveness of the international human rights regime. For many observers, the root problem ailing the regime lies in its toothlessness: enforcement is too weak, abuses go unpunished, and governments violate with impunity. The solution, in this view, is to attach greater political costs to violations in order to incentivize compliance. For instance, Donnelly argues that while the regime’s activities “largely reflect underlying political perceptions of interest,” this may be remedied as the regime develops stronger “monitoring and enforcement procedures” (Reference Donnelly1986, 619). However, we suggest that attempts to strengthen penalties for noncompliance may engender unintended consequences by exacerbating states’ incentives to disproportionately inflict those penalties on their adversaries. Inversely, weaker penalties are necessary if we want states to regularly enforce human rights norms on their allies and partners. The result is a systematic trade-off between strength and selectivity in norm enforcement: human rights enforcement can be stronger, imposing harsh consequences for noncompliance; enforcement can also be fairer, directed at friends as well as enemies. But as long as states are judge and jury, it cannot be both.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001167.

Data Availability Statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/K0XBXX.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article were presented at Dartmouth University (2021), Duke University (2020), Georgetown University (2020), Princeton University (2020), University of Chicago (2021), University of Pittsburgh (2020), University of Wisconsin-Madison (2020), and Washington University in St. Louis (2021). For helpful comments, we thank the participants at those workshops, as well as Lotem Bassan-Nygate, Zoltán I. Búzás, Valentina Carraro, Austin Carson, Miles Evers, Robert Gulotty, Mariya Grinberg, Dustin Tingley, Andrea Vilan, Erik Voeten, the journal editors, and three anonymous reviewers. We are grateful to Giácomo Ramos for excellent research assistance.

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.