INTRODUCTION

Despite much research effort, the importance of Social Capital (SC) determinants is not fully understood and its main mechanisms of formation remain largely untested. In the literature, SC formation is linked to individuals’ characteristics, such as gender, race, age, and education, as well as to contextual variables including inequality, racial diversity, institutions, and political designs (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000; Freitag Reference Freitag2006; Hero Reference Hero2007; Putnam Reference Putnam2000). Building on these insights, we construct and estimate an eclectic empirical model, taking into account several parameter identification and statistical issues generally overlooked. Our setup opens the black box of aggregate data indices, often used in empirical analysis, to portray the multiple aspects of SC formation, recognizing their heterogeneity and interrelation. Using the model, we test hypotheses advocated by various strands of the literature in two applications. First, using unusually rich contextual data, we estimate a model for Chile to understand what determines participation and trust at the municipal level. Second, we estimate comparable models of SC formation for the USA, Mexico, Brazil, and Chile. From our empirical exercises, we reconceptualize certain aspects of SC formation.

We highlight multiple aspects of SC formation. First, we focus on participation in social organizations (Putnam Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000) as a rational-choice individual SC investment, given personal and contextual characteristics. Second, we consider social effects of individual decisions, i.e., participation externalities on associative life, an aspect mentioned by Coleman (Reference Coleman1990) and formalized by Durlauf (Reference Durlauf2002). Third, we introduce general trust (Coleman Reference Coleman1990; Newton Reference Newton2006; Putnam Reference Putnam1993) as a key determinant of social participation, and explicitly deal with its endogenous nature. Fourth, we consider the political and institutional designs in the process of SC formation, as driving forces for associative life and trust (Freitag Reference Freitag2006). Fifth, we study other aspects highlighted in the literature such as income inequality (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000), and make international comparisons (Klesner Reference Klesner2007; Rossteutscher Reference Rossteutscher2008). Finally, we consider several arenas of social participation (religious, parental, community, professional, and political associations), acknowledging their heterogeneity and mutual influences.

Our model is based on a utility maximization problem of participation intensity, given individual and contextual variables. To identify the causal effect of trust on participation, we use crime victimization as an instrumental variable (IV), employing the framework of Angrist, Graddy, and Imbens (Reference Angrist, Graddy and Imbens2000). We borrow from Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008) to build a linear model amenable to standard IV techniques that appropriately traits the ordinal nature of empirical measures of participation and trust. Finally, we allow for free cross-equation correlations across multiple kinds of participation and trust intensities.

Our first application estimates a model for the SC formation process in Chile, a country with solid economic and institutional performance in Latin America (Kalter et al. Reference Kalter, Phillips, Espinosa-Vega, Luzio, Villafuerte and Singh2004). With rich information at the municipal level, we study key factors for individual SC formation at the municipal level (Freitag Reference Freitag2006). We address the role of government institutions on SC formation that other papers neglect (Oxendine et al. Reference Oxendine, Sullivan, Borgida, Riedel, Jackson and Dial2007). We choose this focus because municipalities are the primary link between people and government (Hiskey and Bowler Reference Hiskey and Bowler2005). Moreover, Chilean municipalities are comparable to one another in a single unitary political and economic national context. Municipal data sources are the CASENFootnote 1 household survey; the SINIMFootnote 2 database with institutional, budgetary, and performance measures at the municipal level; and the SERVELFootnote 3 electoral database. Both of our applications use the LAPOPFootnote 4 database, which provides individual data on participation, trust, and other personal characteristics.

For the detailed Chilean case, all mechanisms of SC formation are relevant. The importance of each element varies from one kind of participation to another, confirming the inner heterogeneity of the SC formation process. Only religious participation and trust are explained by social effects. Political-institutional factors seem relevant in all categories, except parental and professional. The mayor's political party affects parental and community participation. Inequality within educational groups has a negative impact for community participation, while inequality between groups negatively affects religious, professional, and political participation. Community and political participation are lower for middle-class municipalities. The Chilean earthquake of 2010 promoted more intense community and professional participation, but individual experiences of vandalism and neighborhood damages hurt trust.

Our second application estimates SC formation models for comparisons across the three most populated democracies in the Americas (USA, Brazil, and Mexico) and Chile. This exercise uncovers relevant individual-level features for multiple kinds of participation and trust, controlling for geographical and time effects. The comparisons show few regularities among the countries studied. To some extent, the SC formation in the USA is the most distinctive. Female participation in religious and parental categories is greater in all cases, except the USA. Compared to the other countries, the USA age profiles show relatively higher participation and trust among the elderly, except for the parental category. Schooling increases all kinds of participation and trust in the USA, and all except religious in Mexico, but has considerably lower impact in Brazil and Chile. Race/ethnicity is also a stronger factor behind SC formation in the USA. Married individuals participate more in religious and parental organizations in all cases.

In both applications, a trust reduction triggered by being a crime victim (or receiving a bribe request) generates an increase of participation, except for nonsignificant effects in Chile for some categories. Presumably, due to the loss of trust, individuals become involved more in organizations to interact with people sharing similar values and interests. Nevertheless, the evidence also shows that unobserved participation and trust factors, probably psychological or cultural features, are strongly positively correlated. Together, these results suggest that (1) in Chile, SC formation is largely determined by individual observable traits, with contextual factors playing a secondary role (except for political); (2) in both applications, exogenous negative shocks to trust spur participation, at least among people more sensitive to crime, suggesting that self-interest actions may generate SC formation; and (3) unobserved idiosyncratic traits jointly produce higher trust and participation, inducing a noncausal positive correlation that could be misunderstood as a “virtuous circle” of SC creation. Thus, our empirical approach to SC formation uncovers factors hidden by assumptions in some of the previous literature.

LITERATURE BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTUALIZATION

The SC research agenda, starting with Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1980) and Coleman (Reference Coleman1990), highlight the complex relationship among individual and collective decisions, social structures, and trust in general. For these authors, associative life is mainly driven by individuals’ rational decisions.

The SC literature presents little consensus on the relevant processes of originating SC (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2006; Hero Reference Hero2007), as well as its appropriate measurement (Bjørnskov Reference Bjørnskov2006; Newton Reference Newton2006). Instead, the prevailing focus is on the effects of SC on a variety of topics, such as civic engagement and democracy (Kim Reference Kim2005; Maloney, van Deth, and Roßteutscher Reference Maloney, van Deth and Roßteutscher2008; Putnam Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000), and a number of economic outcomes (David, Janiak, and Wasmer Reference David, Janiak and Wasmer2010; Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004; Knack and Keefer Reference Knack and Keefer1997). SC formation is usually measured as participation in organizations, associative life, and related indicators (Putnam Reference Putnam2000), usually linked to civic attitudes, trust, and social networks (Putnam Reference Putnam1993; Von Erlach Reference Von Erlach2005). Many studies consider associative life as a subject of study in cross national and subnational comparative research (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000; Freitag Reference Freitag2006; Wagle Reference Wagle2006), which justifies our focus on the investment in SC via involvement in organizations or participation. Consequently, we take participation in social activities as a quantification of the individual's involvement in social networks.

Like Putnam (Reference Putnam2000), many researchers construct indices of SC using ad hoc addition of categorical variables or factor analysis, imposing strong a priori constraints on multiple SC facets. These practices seem misaligned with the evidence (Bjørnskov Reference Bjørnskov2006), and complicate our learning about factors that explain SC formation. Moreover, the relation between trust and participation is weak or even negative in some individual-level studies (Rossteutscher Reference Rossteutscher2008; Rothstein and Stolle Reference Rothstein and Stolle2008). Similarly, the aggregation of different kinds of participation seems unfounded. Putnam (Reference Putnam2000) reports that individual factors (ethnicity, age, etc.) specifically affect kinds of participation. Organizations attract specific people, and offer particular networks, norms, values, and styles that may oppose or complement other groups. For instance, race and ethnicity explain involvement differences between “bonding” and “bridging” types of association (Manzano Reference Manzano2004, Reference Manzano2007).

A rational choice perspective on participation naturally entails an empirical individual-level approach. The SC literature considers individual socioeconomic and demographic variables to explain participation and civic engagement (Morjé and Gilbert Reference Morjé and Gilbert2008; Von Erlach Reference Von Erlach2005). Resources, tastes, and needs that determine participation vary with education, age, gender, marital status, race, and religion. Education provides skills useful for social interactions. Life-cycle and generational aspects shape social participation (Putnam Reference Putnam2000). Gender matters due to biological and socially defined cultural differences. Family characteristics simultaneously impact needs, tastes, and available resources for social participation. Race and religion affect a cultural background linked to individual choices, and interact with community characteristics (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000; Hero Reference Hero2007). Putnam (Reference Putnam2000, 94) highlights correlations among several forms of associative life: “doing any one of these activities substantially increases your likelihood of doing others.” We open the black box of ad hoc SC indicators by addressing the distinctiveness among types of participation, as well as their mutual connections.

Trust is key for achieving economic and political goals (Coleman Reference Coleman1990; Newton Reference Newton2006; Putnam Reference Putnam1993). The “virtuous circle” between trust and participation is seemingly a central conception in SC (Brehm and Rahn Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Putnam Reference Putnam1993). However, the direction of causality between trust and participation could run both ways. Instrumental variable (IV) techniques use quasiexperimental exogenous variation to disentangle one causality direction.

To study SC, researchers consider multilevel empirical strategies, comparing some components of SC across countries, or regions within a country. Some studies only deal with aggregate data, following the path of Putnam (Reference Putnam2000) and Keele (Reference Keele2005). Others focus on subnational explanatory factors, keeping an aggregate perspective (Freitag Reference Freitag2006; Hero Reference Hero2007; Hiskey and Bowler Reference Hiskey and Bowler2005). A third branch links individual and aggregate subnational data to study the influence of economic, political, and institutional context factors (Brehm and Rahn Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Glaeser, Laibson, and Sacerdote Reference Glaeser, Laibson and Sacerdote2002; Letki Reference Letki2006), or racial fragmentation and income inequality (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000, Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2002; Letki Reference Letki2008; Tesei Reference Tesei2012) on individual responses. This research helps us understand the SC formation at the microlevel, a perceived weakness of SC theorists (Hero Reference Hero2007; Rothstein and Stolle Reference Rothstein and Stolle2008). Here, we also present an international perspective along similar lines. Klesner (Reference Klesner2007) provides evidence for Latin American countries, showing that participation in nonpolitical organizations and trust are associated with greater civic engagement.

The idea that social behavior is more than the sum of individual participation choices is core in SC theory (Coleman Reference Coleman1990). Durlauf (Reference Durlauf2002) formalizes the empirical analysis of these issues, building on Manski (Reference Manski1993). The SC literature also associates the impact of political design and institutions in SC creation (McLaren and Baird Reference McLaren and Baird2006). Freitag (Reference Freitag2006) discusses that local government autonomy, efficiency of government policies, expenditure, and consensus democracy potentially influence SC formation.

MODELING PARTICIPATION USING UTILITY INDEX

Following Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1980) and Coleman (Reference Coleman1990), individuals obtain emotional, social, and monetary gains through their interaction in social networks, but also have pecuniary and time-use costs for associative life. In our model, individuals choose a continuous participation intensity in social activities to maximize their net benefit, given a vector of individuals’ characteristics X, and the political and institutional context variables vector Y,

Assuming that the benefit function B(P; X, Y) is increasing and strictly concave, and that the cost function C(P; X, Y) is increasing and convex, the optimal intensity equalizes the marginal benefit and the marginal cost of participation intensity. The latter condition implicitly defines an optimal choice of intensity depending on X and Y, P = G(X, Y), depicted in Figure 1 in terms of weekly hours devoted to participation. The net utility index obtained from participation activities has a bliss point, which defines the optimal individual behavior, given X and Y.

FIGURE 1. Determination of Optimal Participation Intensity

For various reasons presented in Valdivieso (Reference Valdivieso1998), individuals are naturally inclined to participate and cooperate, but face opportunity costs varying according to individual and contextual characteristics. We express P(X, Y) as a linear approximation,

Incorporating Social Effects

The seminal paper by Manski (Reference Manski1993) presents a model with social interactions to study how social behavior influences individual behavior. Thus, in our setup an individual participates more in a community with high participation of others because of benefits associated to large networks. Thus, we introduce aggregate participation as a right-hand side variable,

Individuals forecast using all information, assuming common knowledge of participation equation (1) and availability of the information set Ω m(i) = (X m(i), Y m(i)) for all i in m(i). A rational individual computes the expected participation value as

Substituting back into equation (1) yields

When population characteristics matter in individual choices, there are externalities in the process of SC formation, which allows testing for social effects (Manski Reference Manski1993). The individual participation intensity decision changes incentives for others’ choices. The model expresses an equilibrium in which (1) individuals make their decisions according to the aggregate participation intensity, and (2) individuals’ participation choices are consistent with aggregate behavior.

In a setup of continuous participation intensity with potential social effects and no endogenous regressor such as trust, the parameters are identified if there is at least one Xi whose municipality average level X m(i) does not affect participation intensity (Durlauf Reference Durlauf2002). This is not necessary in our detailed model for Chile because municipal averages X m(i) and individuals’ Xi variables come from different sources (CASEN and LAPOP datasets, respectively). Moreover, we can test for social effects in equation 2 by studying the joint significance of the parameters associated with X m(i) (Manski Reference Manski1993).

Introducing Social Trust

Our conception of trust is a continuous latent variable observed in discrete categories, a standard approach in empirical models of discrete choice (Train Reference Train2009). To some extent, it resembles the amount of money players give in the first round of trust games (Glaeser et al. Reference Glaeser, Laibson, Scheinkman and Soutter2000; Migheli Reference Migheli2012). However, experimental information is generally unavailable, and inappropriate to study participation behavior, especially when the context is important.

On one hand, an individual's trust in others influences social participation by changing the expected payoff that a person could obtain in his or her local network. On the other hand, trust depends on the interaction with reliable people in social networks, what Uslaner (Reference Uslaner2002) calls strategic trust. Due to the mutual causation, identifying a causal effect of trust on social participation is hard, and its sign is uncertain. While the most popular rationale indicates a positive relationship (Putnam Reference Putnam2000), some evidence points in the opposite direction (Rossteutscher Reference Rossteutscher2008; Rothstein and Stolle Reference Rothstein and Stolle2008, and references therein). A shock to generalized trust may weaken ties to strangers but strengthens the ones to particular groups, a possibility supported by evidence showing that trusters have less interpersonal engagement in some dimensions (Uslaner Reference Uslaner2008). If we abstract from potentially heterogeneous responses and correlations between kinds of participation, the simultaneous determination of trust and participation is represented by these equations:

Estimating equation (3), without considering its simultaneous determination leads to a bias such thatFootnote 6

We use an instrumental variable Z, which provides a quasiexperimental source of variation for trust that allows us to disentangle its causal impact on participation. The modern literature on IVs emphasizes heterogeneous responses of the outcome (participation) to changes of trust, induced by changes of an instrument Z.Footnote 7 Heterogeneous responses make identification of average effects harder because individuals respond to the instrument in different ways. Angrist, Graddy, and Imbens (Reference Angrist, Graddy and Imbens2000) show the assumptions for estimating a local average treatment effect (LATE) for the case of a continuous treatment:

-

1. Independence: The instrument Z is independent of the outcome P conditional on observable individual and municipal information (Xi , Y m(i)), i.e., Z is as good as randomly assigned given observable exogenous variables.

-

2. Exclusion: Z is excluded from the equation of participation intensity, i.e., all variation of participation caused by Z comes through a trust variation T.

-

3. Relevance: The variable Z is significantly correlated with trust T.

-

4. Monotonicity: For any given pair of instrument levels (Z 1, Z 0), if Z 1>Z 0, then either all individuals i = 1, 2, . . ., I increase their trust, Ti (Z 1) ≥ Ti (Z 0), or reduce it, Ti (Z 1) ≤ Ti (Z 0).

Under the assumptions above, the estimated causal effect of trust T on participation P equals a weighted average of the marginal impact of trust on participation, across the population that changes trust in response to changes of Z. Large and sensitive-to-instrument groups are heavily weighted (Angrist, Graddy, and Imbens Reference Angrist, Graddy and Imbens2000, 504, Theorem 1).

A natural IV is being a crime victim,Footnote 8 conditional on individual and contextual factors. The empirical detrimental effect of crime on trust is established in the literature (Keele Reference Keele2005; Lederman, Loayza, and Soares Reference Lederman, Loayza and Soares2005). Assumptions 1 and 2 combined are usually called “validity.” Despite the crucial importance of these two assumptions for the method, they cannot be statistically tested, only defended on theoretical grounds (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009).

By conditioning on personal and municipal characteristics, we make individuals comparable in terms of observed variables. Hence, being a crime victim is likely to be driven by luck for individuals sharing the same gender, age, educational level, marital status, and racial background (among other traits), who live in municipalities sharing many common features. Moreover, spatial segregation is high and increasing in Chile and Latin America (Sabatini, Cáceres, and Cerda Reference Sabatini, Cáceres and Cerda2001). Indeed, Santiago ranks as the most segregated city among OECD countries, as other Chilean cities (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development 2013). In the case of the USA, despite a decreasing trend in racial urban segregation since the 1970s, segregation by income is on the rise (Watson, Carlino, and Ellen Reference Watson, Carlino and Ellen2006). Thus, individuals live and work in homogeneous neighborhoods, and hence, conditional on individual traits, being a crime victim is similar to a random assignment. A common assumption in the literature, weaker than independence, is the stable unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA), which means that the effects of a “treatment” for one individual do not affect another. Thus, independence may fail if we were to overlook social effects.

Exclusion requires that changes in participation intensity be due entirely to the impact on trust caused by the crime event, conditional on individual and municipality characteristics. A concern is that participation may drop due to the income loss generated by the crime. However, participation requires little resources, other than personal time. Moreover, controlling for municipal characteristics, age, and education, the individual socioeconomic status is held constant after being a crime victim. Intrinsic motivations also are fundamental to explain participation in associations (Degli Antoni Reference Degli Antoni2009).

Relevance (no weak instruments), a key issue in recent literature, can be tested, defining an acceptable bias level for IV estimates (Stock and Yogo Reference Stock and Yogo2005). We provide relevance tests in individual equations, such as Cragg and Donald (Reference Cragg and Donald1993) (homoscedastic random errors) and Kleibergen and Paap (Reference Kleibergen and Paap2006) (clustered variance matrix). Critical values are provided by Stock and Yogo (Reference Stock and Yogo2005).

The monotonicity assumption, which is not testable, should hold, conditional on observable characteristics and contextual variables. The IV estimator identifies a LATE for the complier subpopulation, i.e., individuals trusting less due to a crime or bribe request. Such events generate suspicious attitudes toward others’ actions and intentions. Psychological evidence shows that depression, anxiety, fear of crime, and avoidance appear as a consequence of a violent crime (Norris and Kaniasty Reference Norris and Kaniasty1994).

Considering Ordinal Responses

While we postulate a continuous participation intensity, the empirical counterparts are discrete variables. For instance, LAPOP data have four categories of meeting attendance to organizations (“Never,” “Once or twice a year,” “Once or twice a month,” “Once a week”). Because discrete categories are naturally ranked, a logical solution is an ordered probit model if there is a normal random component in the intensity. However, its nonlinear nature impedes the interpretation of the model estimates as a LATE and the formal testing of weak instruments, mostly developed for linear models. We still pursue the standard ordered probit in our Online Appendix.

Instead, our preferred approach transforms the ordinal probit into a linear setup, following the method of Terza (Reference Terza1987), further expanded by Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008), henceforth called linear ordered probit (LOP).Footnote 9 We exploit IV methods due to the linearity of the model. The additional assumption is that the latent variable participation (or trust) intensity is also normally distributed, besides the idiosyncratic error term. Hence, we map the intensity thresholds by defining categories on the normal standard distribution as follows:

\begin{eqnarray}

\widetilde{T}_{i}&\equiv& \mathbb {E}\left[T_i | C_{k(i)-1} \le T_i < C_{k(i)}\right]\nonumber\\

& =& \frac{\phi (C_{k(i)-1}) - \phi (C_{k(i)})}{\Phi (C_{k(i)}) - \Phi (C_{k(i)-1})},

\end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray}

\widetilde{T}_{i}&\equiv& \mathbb {E}\left[T_i | C_{k(i)-1} \le T_i < C_{k(i)}\right]\nonumber\\

& =& \frac{\phi (C_{k(i)-1}) - \phi (C_{k(i)})}{\Phi (C_{k(i)}) - \Phi (C_{k(i)-1})},

\end{eqnarray}

The variance matrix of the estimates of (7) and (8) requires an adjustment to account for measurement errors included in

![]() $\widetilde{u}_i$

and

$\widetilde{u}_i$

and

![]() $\widetilde{v}_i$

. Analytical results are hard to obtain due to endogenous regressors and cross-equation correlations. Hence, we compute a bootstrapped variance matrix to test our hypotheses, including participation and trust measurement errors in all repetitions (nearly 500).Footnote

10

$\widetilde{v}_i$

. Analytical results are hard to obtain due to endogenous regressors and cross-equation correlations. Hence, we compute a bootstrapped variance matrix to test our hypotheses, including participation and trust measurement errors in all repetitions (nearly 500).Footnote

10

Considering Multiple Participation Categories

There are five kinds of social organizations in LAPOP data: religious, parental, community, professional, and political. Since individuals simultaneously choose a participation intensity in each category, these choices are interrelated. These kinds may be complements or substitutes. Participation in certain activities may change the net benefit of participation in other types.

We allow for free contemporaneous correlations across participation and trust equations. Hence, we have a six-dimensional recursive LOP model, estimated via simulated LIML (SLIML). We use numerical integration with the GHK (Geweke, Hajivassiliou, and Keane) simulation method (Geweke and Keane Reference Geweke and Keane2001; Train Reference Train2009) and

![]() $3\sqrt{N}$

draws from Halton sequences, a quasi–Monte Carlo sampling method, where N stands for the total number of observations.Footnote

11

Fortunately, Roodman (Reference Roodman2011) code cmp for Stata (Version 12.1) suits our needs. The full structure of the likelihood of this model is in our Online Appendix.

$3\sqrt{N}$

draws from Halton sequences, a quasi–Monte Carlo sampling method, where N stands for the total number of observations.Footnote

11

Fortunately, Roodman (Reference Roodman2011) code cmp for Stata (Version 12.1) suits our needs. The full structure of the likelihood of this model is in our Online Appendix.

DATA SOURCES AND VARIABLES

Individual-Level Variables

The source for measurements of individual participation are LAPOP surveys for 2008, 2010, and 2012 for Chile and the USA. In the case of Brazil, we add the 2006 survey. For Mexico, we can also include the 2004 survey. Interpersonal trust is measured through the following question: “Would you say that people in your community are very trustworthy, somewhat trustworthy, not very trustworthy or untrustworthy?” We order categories from low to high intensity. Descriptive statistics are displayed in Table A1 in the Online Appendix. Individual characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, religion, schooling, and urban status are also in LAPOP.Footnote 12 In addition, we include geographic dichotomic variables (states for the USA, Brazil, and Mexico, and regions for Chile).

Municipal Demographic Variables

To test for social effects of participation in Chile, we obtain data on average demographic characteristics such as gender, education, etc., at municipal level from the 2006, 2009, and 2011 CASEN surveys, although the measures are not perfectly contemporaneous with LAPOP individual-level variables. In the case of measurement errors of these variables, finding significant social effects would be harder since our estimates would be biased towards zero (attenuation bias). Part of Table A3 in the Online Appendix summarizes these data.

Institutional, Political, and Other Context Variables

The institutional, budgetary, and administrative data of municipalities are obtained from SINIM 2008, 2010, and 2012. Among these variables in Table A3, we consider contextual data including the population density (thousands of inhabitants per square kilometer), and the log of average per capita municipal household income. We also report statistics on the effects of the 8.8 Richter earthquake that occurred in Central Chile on February 27, 2010. The LAPOP 2010 survey contains individual-level reported vandalism or neighborhood physical damages due to the earthquake, as well as the Mercalli squared intensity scale in the region of residency, to allow for a marginal impact increasing in Mercalli intensity.Footnote 13 An event of such magnitude exposes individuals to unusual situations that change their beliefs in the community and their behaviors.

Table A3 in the Online Appendix presents basic Chilean local government statistics on the log of social organizations per capita (including sport, women, parental, community, and other municipal organizations); the log of expenditure in social organizations per capita (including transfers to social organizations, and expenditures in the community, and volunteer organizations); and log municipal average subsidies. While the first two variables are expected to increase participation, subsidies may generate different effects on categories, depending on the impact of additional income on individual decisions, and associated incentives. We expect that budgetary self-funding capacityFootnote 14 increases the autonomy of municipalities, focusing on local priorities, and spurring participation.

Managerial efficiency of municipalities may also affect participation. The quality of public policies influences democratic governance and sustainability, affecting participation (Hagopian and Mainwaring Reference Hagopian and Mainwaring2005; Kim Reference Kim2005). We measure efficiency as the gap between the actual average of language and math test scores (SIMCE) of fourth-grade students in municipal schools, and a theoretical benchmark because people may evaluate mayors through their managerial efficiency of local public schools. The measure is constructed as a predicted value of a regression of the average SIMCE test score on variables capturing socioeconomic status (averages of log family income, schooling, age, and poverty), scale and congestion effects (log of population, density of population), and regional dummies.

The literature highlights that consensus democracy fosters participation more than majority democracy does. When majority and minority citizens are involved in policy decision making and monitoring, participation increases (Freitag Reference Freitag2006). To measure voting consensus in each municipality, we construct a Herfindahl index of voting concentration. Used as a measure of industry concentration, it is computed as the sum of squared voting shares of each candidate in the last mayoral election. We also consider the impact of the political party of the mayor, counting the five most important Chilean parties.Footnote 15 We hypothesize that some parties may affect certain social organizations of citizens due to their ideologies. We also include the voting share of the mayor in office, since it captures local political leadership on citizen participation.

Inequality Measures

Income inequality and racial diversity empirically discourage participation and trust levels (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000, Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2002; Hero Reference Hero2007). While racial composition is homogeneous in Chile, the country is socially and spatially segregated (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development 2013). Following Tesei (Reference Tesei2012), who finds that inequality between racial groups affects trust in the USA, we consider inequality between and within educational attainment groups, resembling high and low socioeconomic classes. A Theil municipal inequality index equals the sum of “within” and “between” Theil indices for each class. These two sources of inequality may have different impacts on participation categories. We also explore the municipal and regional Gini coefficients as measures of inequality, as well as the municipal poverty rate in our Online Appendix.

ESTIMATION AND RESULTS

Detailed Model for Chile

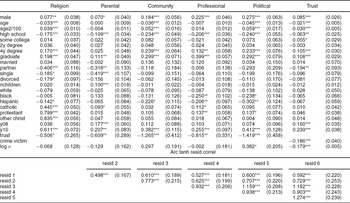

Tables 1 and 2 display the SLIML estimates of the multivariate LOP model for five types of associational life and trust. Because linear ordered models assume a continuous participation intensity with a standard normal distribution, a coefficient represents the standard deviations of participation (or trust) intensity generated by a marginal change of the related explanatory variable. For instance, the effect of being male is −0.182 standard deviation (SD) for participation in religious organizations, being significant at 1% (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. Full Model SLIML Linear Ordered Probit Model for Chile (Part 1)

TABLE 2. Full Model SLIML Linear Ordered Probit Model for Chile (part 2)

Notes: Observ = 4,430; Log Likelihood = −25,693; McFadden pseudo R 2 = 0.04702; Cragg-Donald test = 19.398; Kleinbergen-Paap = 18.111. Linear ordered probit estimates (Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008) using cmp Stata 12.1 code (Roodman Reference Roodman2011). Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses with approximately 500 repetitions. Significance: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. UDI = Democratic Independent Union Party, RN = National Renovation Party, PDC = Christian Democratic Party, PPD = Party for the Democracy, PS = Socialist Party.

To learn about relevant factors, we compute several p-value of Wald tests to assess (1) overall significance of a factor; (2) factor significance for a particular kind of participation; and (3) equal effects for all kinds of participation, a fair comparison since intensities are standardized. The first column of Table 3 shows that all individual factors are significant, except race. The last column shows significant differences across kinds of participation, except income inequality (in the margin) and individual race. These findings empirically justify the study of the SC formation process considering heterogeneous participation types.

TABLE 3. Hypothesis Testing: Full Model for Chile

Notes: 100 × p-values of Wald tests reported using bootstrapped variance matrix. P-values lower than 5% are highlighted. In the first column, we test joint significance of corresponding variables. We test significance by kind of participation in columns 2–7. In the last column, we test for the equality of impacts across participation types.

We report the McFadden R 2 = 0.047 as a standard goodness-of-fit measure for maximum likelihood models. While this magnitude may seem modest, the whole contribution of explanatory variables increases the joint likelihood by roughly 1268%.Footnote 16 Equation measures of goodness of fit are the log of standard deviation of the equation's error term log σ. In Table 2, we can see that religious participation has the poorest fit, while political participation has the best. Correlations between error terms are shown as their hyperbolic arctangent that monotonically maps the interval [−1, 1] into the real line.Footnote 17 Finally, we report the Cragg and Donald (Reference Cragg and Donald1993) and Kleibergen and Paap (Reference Kleibergen and Paap2006) tests for weak instruments. Both compare favorably to critical values of Stock and Yogo (Reference Stock and Yogo2005), suggesting that equation-by-equation IV estimator biases are substantially lower than 10% of OLS estimates.

Religious

The first columns of Tables 1 and 2 show that males participate significantly less than women in religious organizations. Tables 1 and 3 jointly show a significant increasing convex age profile. This is consistent with a life-cycle hypothesis, in which individuals find psychological alleviation in religious beliefs as they grow older. We cannot rule out an alternative cohort explanation: the elderly are more religious than the young. While family (marital status, and number of children) matters for religious participation, race does not (see Table 3). All Christian groups participate more, led by Protestants and Evangelicals. Table 3 shows that social effects are significant for this category. Time effects show a declining trend in religious participation over time.

Political-institutional factors are significant in the baseline model, as shown in Table 3. Among these variables, an increase of 1% in municipality real family average subsidies raises religious participation by 0.183 SD, suggesting specialization in obtaining government assistance by religious associations. An increase of 1 SD of SIMCE test score with respect to the benchmark increases the participation intensity in 0.139 SD, supporting claims linking the quality of public policy to participation (Freitag Reference Freitag2006). Inequality between socioeconomic groups (college vs. noncollege) significatively reduces religious participation, and average income per capita raises it. Thus, religious participation is stronger in high and relatively homogeneous socioeconomic-level municipalities. Remarkably, a trust reduction due to a crime experience significantly increases religious participation, for individuals shifting their trust intensity (LATE effect, as in Angrist, Graddy, and Imbens Reference Angrist, Graddy and Imbens2000). This result is highly significant and robust across additional specifications in our Online Appendix as well.

We interpret that religious organizations attract individuals with a trust loss who seek a network sharing moral precepts that signal trustworthiness. This agrees with evidence of leery individuals having more frequent interactions with their relatives (Uslaner Reference Uslaner2008, and references therein). We estimate the model assuming that trust is exogenous in Tables A4 and A5 of our Online Appendix, yielding a positive nonsignificant coefficient. Equation (5) suggests that there may be a positive marginal impact of participation on trust, in line with SC (trust) formation through participation. To some extent, our evidence supports Uslaner (Reference Uslaner2002, Reference Uslaner2008) instead of the “virtuous circle” of Putnam (Reference Putnam2000).

Cross-equation correlations show that unobserved factors behind religious participation are significantly positively correlated to unobserved factors spurring participation in parental centers, community organizations, and trust. Christian churches (in particular Catholic) own many schools in Chile and actively influence local communities, linking religious, parental, and community associations.

Parental

Participation intensity in school parent associations is lower for non-Christians and “mestizos.” Gender differences are large: males’ participation intensity is 0.339 SD lower than females’. Married individuals participate somewhat more than partners or divorcés; in turn, these categories surpass singles’ intensity. There is also a significant life-cycle age profile, implying a peak at 27.7 years old, similar to previous evidence (Glaeser, Laibson, and Sacerdote Reference Glaeser, Laibson and Sacerdote2002; Putnam Reference Putnam2000). Trust LATE is negative but nonsignificant for this kind of participation. Aggregate demographic variables at the municipality level, as well as factors related to the 2010 earthquake, are not individually significant.

Among political-institutional factors, an increase of 1% in the number of organizations per capita raises parental participation intensity in 0.05 SD, which suggests that institutional support matters. In addition, a Party for Democracy (PPD) mayor in office reduces parental participation by 0.15 SD. This may be interpreted as a substitution of parents’ efforts in communities ruled by a leftist mayor advocating greater government influence on educational policies.Footnote 18 Table 3 shows that institutional factors affect parental participation at 10% of significance. There is no evidence of trends, nor influence of unobserved factors related to other categories.

Community

Participation in “Committee meetings to improve community” is significantly lower for males and higher for Catholics. Urban individuals in low population density areas participate more, indicating that the suburban lifestyle promotes community associativity. The significant participation age profile is hump shaped, peaking at age 86.2, suggesting either a generational decline, or a genuine life cycle of community participation. We also find nonsignificant social effects. The evidence shows larger intensity in 2008, a drop in 2010, and an increase in 2012. Estimations suggest that the 2010 earthquake intensified community participation. For instance, the Maule and Biobío regions (Mercalli intensity of 9) had an increase of 0.194 SD.

Institutional variables jointly matter for this sort of participation, as shown in Table 3. Subsidies significantly increase participation. Having a National Renovation Party, Socialist Party, or Christian Democrat Party mayor significantly increases community participation. This could be partially explained by parties’ organizational structure, a hypothesis raised by Joignant (Reference Joignant2012). Income distribution has a complicated effect on community participation. While the poverty rate has a large and significant impact on community participation intensity (an increase of 1% of poverty rate increases intensity by 0.017 SD), the average income also increases this intensity. In addition, Theil inequality index within socioeconomic groups deters community participation. Together, this evidence suggests that community participation is stronger in poor or rich but relatively homogeneous municipalities. Conversely, middle-class heterogeneous municipalities participate less, possibly due to difficult coordination among individuals pursuing conflicting goals. In this case, the marginal local average impact of trust does not generate significant changes in participation. Finally, the unobserved factors of other kinds of participation are jointly significant to explain community participation.

Professional

Participation intensity in “professional, merchants, producers, and farmers associations” is significantly higher for male and urban individuals. The effect of age describes a significantly hump-shaped profile peaking at age 58.1. Education also shows a significant increasing and convex profile for six or more years of schooling. The earthquake significantly revitalized professional associations in the most affected areas (measured through the Mercalli index squared). After the disaster, professional organizations received an unusual demand for their collective specialized action. Among contextual variables, only inequality between educational groups negatively impacts professional participation. Idiosyncratic factors of other categories, especially community, increase this professional participation.

Political

Gender and marital status are not statistically significant in this category. Catholicism negatively affects participation intensity. Political participation shows a hump-shaped age profile, peaking at age 52.4. The education profile is significantly increasing and convex for individuals with more than 6.7 years of schooling. In addition, the estimates show a significant decreasing trend since 2008. Table 3 shows that political participation is the less influenced category by individual factors in relative terms. Aggregate composition of age and education significantly impacts political participation, reflected into social effect, significant at 12.5% (see Table 3).

Among institutional and contextual variables, the availability of organizations and a greater population density significantly decrease political participation intensity, perhaps by facilitating people engaging in alternative social networks. Moreover, a mayor of the rightist UDI party increases intensity participation. High and low classes seemingly participate more as per capita family income and poverty rate positively affect this category. Inequality between socioeconomic groups has a negative effect, suggesting more difficult political coordination under a mixed composition of social classes. Unobserved factors behind professional participation are significant explanatory factors for political intensity. Income, inequality, political-institutional features, and idiosyncratic factors are the most important factors for this category.

Trust

Among individual variables, urban origin increases 0.188 SD of trust intensity, while being married increases by 0.11 SD with respect to widows. Table 3 shows a significant hump-shaped age profile, peaking at age 30.5. The education effect on trust intensity has an increasing and convex profile for schooling higher than 4.9 years. Religion, family, and gender seem not to affect trust intensity overall. During the municipal election year 2008, trust was 0.269 SD higher than other years. Some aggregate demographic variables are individually significant, aligned with significance of social effects in Table 3. The earthquake significantly affected trust intensity. In municipalities suffering a Mercalli intensity of 9 (Maule and Biobío), individuals increase their trust intensity by 0.218 SD. In contrast, witnessing vandalism or neighborhood damage after the earthquake decreased trust by 0.221 and 0.108 SD, respectively. This suggests that the earthquake impact depended strongly in personal experience. While Chong, Fleming, and Bejarano (Reference Chong, Fleming and Bejarano2011) find a negligible effect of the earthquake on trust, their experiments do not consider personal consequences of earthquakes.

Political-institutional factors significantly explain trust in Table 3. Expenditure in social organizations reduces trust intensity, whereas an increase in income subsidies generates a large increase of trust intensity. This suggests that citizens trust less when government funds are spent in intermediate organizations. Among political variables, an increase of 0.01 units of the Herfindahl index increases trust by 0.113 SD. Together with a negative effect of incumbent mayor voting, trust grows when the political scenario shows few, but electorally strong, candidates. A rise in municipal average income, with significance at 10%, increases trust intensity by a large amount, while income inequality measures do not matter. Trust is greater for individuals participating in religious and community associations. Importantly, being a crime victim decreases trust intensity by 0.159 SD, which confirms that the theoretically and statistically relevant mechanism of the instrument works as hypothesized (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009).

Multiple Countries Model

In this section, we present individual variable effects on participation and trust intensity, displayed in Tables 4–7. Formal hypothesis testing in Table 8 shows that all specific aspects (family, race, religion, age, education, gender, state/regional, time, dependence) are jointly relevant in the SC formation process, with a partial exception of racial aspects in Brazil and Mexico. In addition, the null hypothesis of equal impact of factors on all participation types is strongly rejected in almost all cases, exceptions being racial aspects in Chile, Brazil, and Mexico.

TABLE 4. State Fixed-Effects SLIML Linear Ordered Probit Model for the United States

Notes: Observ = 4,490; Log Likelihood = −24,578; McFadden pseudo R 2 = 0.04274; Cragg-Donald = 26.777; Kleinbergen-Paap = 22.707. Linear ordered probit estimates (Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008) using cmp Stata 12.1 code (Roodman Reference Roodman2011). Controls for state dummy variables are not reported. Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses with approximately 500 repetitions. Significance: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

TABLE 5. Regional Fixed-Effects SLIML Linear Ordered Probit Model for Chile

Notes: Observ = 4,915; Log Likelihood = −28,540; McFadden pseudo R 2 = 0.04616; Cragg-Donald test = 24.546; Kleinbergen-Paap = 41.693. Linear ordered probit estimates (Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008) using cmp Stata 12.1 code (Roodman Reference Roodman2011). Controls for regional dummy variables are not reported; Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses with approximately 500 repetitions. Significance: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

TABLE 6. State Fixed-Effects SLIML Linear Ordered Probit Model for Brazil

Notes: Observ = 6,320; Log Likelihood = −39,383; McFadden pseudo R 2 = 0.03665; Cragg-Donald test = 18.761; Kleinbergen-Paap = 13.207. Linear ordered probit estimates (Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008) using cmp Stata 12.1 code (Roodman Reference Roodman2011). Controls for state dummy variables are not reported. Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses with approximately 500 repetitions. Significance: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

TABLE 7. State Fixed-Effects SLIML Linear Ordered Probit Model for Mexico

Notes: Observ = 7,626; Log Likelihood = −50,430; McFadden pseudo R 2 = 0.03459; Cragg-Donald test = 37.185; Kleinbergen-Paap = 16.275. Linear ordered probit estimates (Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2008) using cmp Stata 12.1 code (Roodman Reference Roodman2011). Controls for state dummy variables are not reported. Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses with approximately 500 repetitions. Significance: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

TABLE 8. Hypothesis Testing: Multiple Countries

Notes: 100 × p-values of Wald tests reported using the bootstrapped variance matrix. P-values lower than 5% are highlighted. In the first column, we test joint significance of corresponding variables. We test significance of variables by kind of participation in columns 2–7. In the last column, we test for the equality of impacts across participation types.

State/regional effects (capturing local idiosyncratic institutional effects) have significant explanatory power for all kinds of participation in Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. In sharp contrast, geographic variation is only important for trust in the USA. Remarkably, unobserved idiosyncratic aspects are significantly positively correlated among categories (see bottom panels of Tables 4–7). This suggests that individual personality or cultural traits simultaneously motivate participation of various kinds in all countries studied, linking different manifestations of SC. Time effects show an overall increase in all kinds of participation and trust in 2010 for the USA, coincidental with several elections; Mexico shows a declining trend in many categories. Brazil and Chile seem more stable. In Tables 4–7, both Cragg and Donald (Reference Cragg and Donald1993) and Kleibergen and Paap (Reference Kleibergen and Paap2006) show relevant instruments, indicating that IV estimator bias should not worry us.

Religious

Among studied countries, religious participation is atypical for the USA. Male participation intensity is significantly higher than female's in the USA, a pattern reversed for the other countries. Figure 2 depicts the U-shaped age profile of the USA for religious participation; in contrast, Chile, Brazil, and Mexico show profiles increasing with age. Wald tests in Table 8 shows that age is a significant factor in all cases. Education also increases religious participation in the USA, but is nonsignificant in Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. USA individuals with a graduate or college diploma exhibit higher than average participation intensity, while high school graduates participate less than average. Participation intensity in the USA is lower for partner, single, and divorced individuals, a result similar to Brazil and Mexico. We found no effect of number of children, as opposed to Alesina and La Ferrara (Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000). Hispanic origin decreases by 0.142 SD of participation intensity with respect to other ethnic groups (omitted category) in the USA. Religious participation in the studied countries is significantly higher for Christian religions compared to non-Christians. Among Christians, Catholics show lower intensity. Trend patterns are quite different in the four analyzed countries.

FIGURE 2. Age Profiles of Participation and Trust: USA, Chile, Brazil, and Mexico

A decrease of trust intensity of one SD significantly increases religious participation intensity by 0.3–0.6 SD for different countries. Our estimates neglecting endogeneity in our Online Appendix (Tables A6–A9) show either positive significant effects (USA, Brazil) or nonsignificant ones (Chile, Mexico). These results confirm endogeneity between trust and participation. Correlations across equations are particularly strong in the USA, less remarkable in Brazil and Mexico, and even milder in Chile.

Parental

For this category, females show significantly greater intensity in all the countries, except the USA. Age profiles in Figure 2 show hump-shaped profiles, except for the USA, which is decreasing and not significant according to Table 8. Education significantly increases parental intensity only in the USA and Mexico. Family aspects are important for all countries, showing that married/partner status (compared to singles) and the number of children increases intensity. Racial factors are nonsignificant. Religious affiliation has distinct impacts: in the USA and Mexico, Catholics participate the most; in Brazil, protestants and evangelicals prevail; in Chile all Christian groups are similar. As in religious participation, a negative impact on trust generated by a crime experience locally increases participation, with the exception of Chile. When endogeneity is neglected (Tables A6– A9 in the Online Appendix) there are positive significant effects for the USA and nonsignificant ones for the rest. There are significant cross-equation correlations for all countries, with lower strength in Chile.

Community

This participation is significantly higher for males, except in Chile. Urbanization deters participation in Brazil and Mexico, but the opposite occurs in Chile. Figure 2 portrays a similar age profile for Chile, Brazil, and Mexico, but suggests a stark rise in community participation among the elderly in the USA. Education significantly raises intensity in the USA, Brazil, and Mexico, but not much in Chile (see also Table 8). Family issues matter little in most countries, with the partial exception of Mexico (joint significance in Table 8). Racial aspects suggest that Hispanics have lower participation in the USA; in Chile and Brazil, these issues are not relevant; in Mexico, aboriginal individuals and whites participate more. For Chile and Mexico, Catholics exhibit greater participation in community, while in the USA and Brazil, religion plays no significant role. As in the other categories, a reduction in trust due to crime experience generates a significant local increase in community participation for individuals more sensitive to crime, except in Chile. Not accounting for endogeneity, this misleads us to a positive impact of trust on participation in community issues (among trust changers) as shown in the Online Appendix, Tables A6– A9, except for a nonsignificant effect in Brazil. Cross-equation correlations are significant in all cases.

Professional

This category of participation exhibits greater intensity for males, especially in the USA. While urbanization promotes this category in Chile, the opposite occurs in Brazil and Mexico. Age profiles look similar for Chile, Brazil, and Mexico in Figure 2, but the elderly participate relatively more in the USA. Higher schooling spurs participation in the USA, Chile, and Mexico, but not in Brazil. Family aspects do not jointly matter in all countries, but a negative impact of the number of children shows up in Chile and Mexico, similar to the Alesina and La Ferrara (Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000) results. Race is an important determinant for intensity only in the USA, as whites surpass intensity of blacks and Hispanics. Catholics and Protestants participate more in the USA, a feature not shared in other countries. A drop in trust induced by crime experience leads to a significant increase in professional participation, except in the case of Chile. Cross-equation correlations are significant and positive in most cases, the exception being Chile.

Political

Males show greater participation intensity in the USA and Brazil, but not in Chile or Mexico. Urban residents participate less in Brazil and Mexico, but not in Chile. The age profiles shown in Figure 2 are similar to those in community and professional categories for all countries. Family issues are not relevant, as shown in Table 8. Race/ethnic differences are only important in the USA, showing blacks and especially Hispanics as low intensity groups. The impact of Catholicism is significant only for Chile (negative) and Mexico (positive). Political participation has no time trend in Chile and Brazil, in contrast to the USA and Mexico. As in other categories, an exogenous trust change is negatively related to political participation, except in Chile.

Trust

Males trust more in all cases, except Chile. Urbanization affects trust negatively in Brazil and Mexico, but positively in Chile. In Figure 2, we see that older individuals significantly trust more, especially in the USA. We find a positive effect of education on trust levels for all cases but Brazil, as also found by Borgonovi (Reference Borgonovi2012) and van Oorschot and Finsveen (Reference van Oorschot and Finsveen2009). Married people exhibit larger trust intensity than partners (nonmarried couples) and divorced individuals, except in Mexico. The number of children negatively affects trust in Mexico, too. While religion seems not to play a role in the USA, Catholics and Protestants/Evangelicals trust more in Mexico. Finally, being a crime victim shows a large negative impact on trust, as expected. Besides the standard weak instrument tests (Cragg and Donald Reference Cragg and Donald1993; Kleibergen and Paap Reference Kleibergen and Paap2006), this result shows that the instrumental variable works as expected (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009).

Robustness Checks

We consider several variations of our baseline assumptions for our two applications. The detailed results are found in our Online Appendix.

Regular Ordered Probit

In the subsection we explain our preference for the LOP approach instead of a more conventional ordered probit. Since LOP relies on the assumption of normally distributed participation and trust intensities, we estimate and test hypotheses in a multivariate ordered probit to see if our results remain (see section F of the Online Appendix). No major conclusions change from our baseline analysis.

Alternative Instruments

We assess the possibility of alternative instruments satisfying conditions enumerated in the Introducing Social Trust subsection of the Modeling Participation using Utility Index section. Bribe requestFootnote 19 is a variable, reported in LAPOP, serving as a valid source of exogenous variation for trust. In the Online Appendix, section G, we show that its joint use with criminality works in the expected way (i.e., a bribe request deters trust). We also consider the interaction between crime victim experience and gender, as an alternative IV set. A priori, women may be more affected by crime experiences, but this only holds for Mexico. Introducing this additional instrument reduces Cragg and Donald (Reference Cragg and Donald1993) and Kleibergen and Paap (Reference Kleibergen and Paap2006) tests, but the main conclusions do not change, as the tests of hypothesis show in Tables A22, A27, and A32 in the Online Appendix. In all cases, the induced reduction of trust generally spurs participation types. As in the baseline case, we find nonsignificant effects in some categories for Chile.

Municipal Fixed Effects

We formulate and estimate a model with municipal fixed effects for the detailed Chilean case to assess the robustness of contextual factors. We only consider municipalities with more than

![]() $\sqrt{N}$

individuals, N being total number of observations. This specification is a harsh test on the empirical relevance of variables X

m(i), Y

m(i), since their impacts only come from temporal variation of municipal characteristics. However, this test may be too stringent because all cross-sectional contextual variation is taken away. In our Online Appendix, we display the results in section H. Conclusions are quite robust, but some contextual factors become nonsignificant.

$\sqrt{N}$

individuals, N being total number of observations. This specification is a harsh test on the empirical relevance of variables X

m(i), Y

m(i), since their impacts only come from temporal variation of municipal characteristics. However, this test may be too stringent because all cross-sectional contextual variation is taken away. In our Online Appendix, we display the results in section H. Conclusions are quite robust, but some contextual factors become nonsignificant.

Alternative Inequality Measures

In section I of the Online Appendix, we present our results for more conventional measures of income inequality as SC determinants (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000; Hero Reference Hero2007), using Gini indices at the municipal and regional level in Chile. Using these measures, inequality becomes nonsignificant to explain participation types and trust in Chile, in line with complications reported by Hero (Reference Hero2007) for the USA. The rest of our results remain roughly unchanged. This result shows that using a decomposable Theil index allows us to uncover interesting effects of income inequality in Chile.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

Our model provides a better understanding of the mechanisms behind SC formation. With a multiequation empirical model, we acknowledge the connections among aspects emphasized in the literature. Individuals evaluate the costs and benefits of participation in arenas with distinct motives and purposes. Nevertheless, the most common approach assumes that participation choices are a single entity, an aggregate index. We open this black box to learn how these categories are determined and interrelated one to another. We present two applications. First, we jointly assess the role of individual, social, and institutional factors on participation and trust in Chile. Second, we study individual factors motivating participation and trust in the USA, Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. In both applications, we consider often overlooked aspects of identification, endogeneity, ordinal variables, and interrelated decisions. We introduce and test several competing or complementary hypotheses on SC formation advocated in the literature.

What did we learn from these results? First, participation in organizations (SC formation) is a multidimensional and heterogeneous phenomenon. Each kind of associative life is influenced by distinct factors in particular ways. Benefits and costs of different kinds of activities exhibit a substantial interpersonal variation due to individual and contextual factors. We find robust empirical evidence against equal effects of main determinants across different kinds of participation. The diversity of factors and their varying relative importance show that SC formation responds to practical dimensions of life, which is consistent with a rational decision approach. Thus, our empirically based view highlights individual considerations and tones down a communitarian perspective.

Second, we learn which contextual factors explain more across different participation categories, controlling for individual traits, in our first application. Political-institutional factors matter. Since mayors’ political affiliations influence parental, community, and trust categories, ideological or organizational partisan elements transmitted through local governments impact associational life. Monetary subsidies, interactively assigned by central and local governments, impact religious, community, and trust categories. Resources may be targeted to foster certain kinds of participation since religious and social-class cleavages explain Chilean politics (Torcal and Mainwaring Reference Torcal and Mainwaring2003; Valenzuela, Scully, and Somma Reference Valenzuela, Scully and Somma2007). The evidence also suggests that an election with few strong candidates increases trust. Social effects (Durlauf Reference Durlauf2002; Manski Reference Manski1993) influence trust and religious categories, probably spread by moral/ethical precepts of role models. Community and political participation flourish in high- and low-income municipalities. Inequality between educational groups deters professional, political, and religious participation, probably due to coordination obstacles for individuals with conflicting interests. We also show that the 2010 earthquake increased community and professional participation, but had a negative impact on trust if a person witnessed vandalism or neighborhood damages. Therefore, the focus on the impact of contextual factors on individuals emerges as an alternative approach to aggregate visions of SC.

Third, we learn the impact of individual traits on participation decisions, controlling for geographic and time fixed effects in our multicountry model. All countries, except Chile, exhibit greater male participation intensity in community, professional, political, and trust categories. Religious and parental categories show greater female participation intensity in all cases but the USA. Age profiles of participation look similar for Chile, Mexico, and Brazil; the USA shows a much greater relative increase for the elderly in all kinds except parental (see Figure 2). Education is important for almost all types of participation in the USA and Mexico, but this influence is lower in Chile and Brazil. The effect of race is larger in the USA than in the other countries studied. The effect of family factors is similar across studied countries, with married individuals showing greater intensity, in line with Putnam (Reference Putnam2000, 277). In addition, geographical variation within countries is relevant for all participation categories and countries but the USA.

Fourth, we estimate the effect of trust on participation, a perennial issue in SC literature, recognizing endogeneity, heterogeneous causal responses, and the ordinal nature of the data. The evidence, with some exceptions for Chile, indicates a negative local average causal effect on participation due to a negative trust shock (crime or bribe request experience). Our findings are somewhat close to Uslaner (Reference Uslaner2002) and disregard Putnam's virtuous circle, a seemingly predominant view in the literature. Large differences between estimations that consider endogeneity and those that neglect it may be rationalized by a large effect of participation on trust. In response to a negative trust shock, individuals intensify participation in associations with people sharing similar interests and values.

The study of SC formation would be enriched by a Hobbesian conception of human social behavior, since the increase in participation is presumably motivated by higher insecurity and self-interest. This contrasts with a Tocquevillian emphasis on intrinsic cooperative motivation as a source of SC. We highlight rational individual choices, motivated by particular personal features, conditional on contextual factors, which are justified on empirical grounds with fewer restrictive assumptions.

Fifth, we also find positive correlations among idiosyncratic factors, uncorrelated to all observable variables. Presumably, these psychological or cultural individual factors motivate people to trust and to engage in social interactions. Hence, participation and trust may appear positively correlated because some individuals are idiosyncratically prone to participate and trust. However, an adverse exogenous shock to trust generates a participation increase, probably a greater attachment to reliable networks, and a reduction of interpersonal trust. Our deconstruction of SC capital formation disentangles the local causal effect of trust on participation, from factors simultaneously generating them. The former is a true causal effect; the latter is just correlation induced by a third unobserved variable. These concepts are summarized in Figure 3. While we have no estimate of the causal effect of participation on trust, it is probably positive according to results in the Introducing Social Trust subsection of the Modeling Participation using Utility Index section.

FIGURE 3. Schematic Relations of Social Capital Formation

Finally, we merge several considerations in a multidimensional yet interpretable model. Our model tries to take apart SC formation elements like a mechanic disassembles an automobile engine. We know what the engine does, but we need to identify its critical parts and understand how they relate one to another, keeping in mind that they function together. Hopefully, our work provides a deeper understanding of SC formation and helps systematize our knowledge with a rigorous empirical basis.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000658

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.