INTRODUCTION

The discovery that Russia executed a wide-ranging plan to influence the 2016 U.S. Presidential race has sparked a global debate about foreign involvement in democratic politics. Although countries have long interfered in each other’s elections (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2017, Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019; Levin Reference Levin2016, Reference Levin2019b),Footnote 1 the scope and sophistication of Russian activities signaled the arrival of a new era. Changes in information technology now make it possible for states to undertake ambitious influence campaigns in faraway countries, even when outmatched from a conventional military standpoint. Moreover, observers have struggled to identify effective strategies for stopping this potentially powerful form of foreign influence.Footnote 2 One can, therefore, expect more foreign efforts to shape elections in the future.

In this article, we use survey experiments to investigate three fundamental questions about how Americans would respond to revelations of foreign electoral intervention. First, when would U.S. citizens tolerate foreign involvement in American elections, instead of condemning external efforts to tip the scales? Polls conducted after the 2016 election show that Democrats and Republicans expressed different opinions about Russian interference. Democrats were more likely to believe that Russia interfered, more likely to think that Russia altered the outcome of the election, and more concerned about the potential for foreign meddling in the future.Footnote 3

It is difficult to draw general conclusions from this historical episode, however. We do not know, for instance, how Americans would respond if the shoe were on the other foot. If citizens learned that a foreign country had intervened on behalf of a Democratic candidate, would Democrats denounce the foreign intervention as an unacceptable attack on American democracy, or would they condone the foreign assistance? Would Republicans change their tune, as well, disapproving more strongly of foreign aid for a Democratic candidate than for a Republican one? Would public reactions depend not only on the intended beneficiary of the intervention but also on the form of meddling? Data from 2016 cannot provide the answers, but we can investigate these issues systematically through experiments.

This article also uses experiments to address a second fundamental question: when would news of foreign electoral intervention undermine confidence in democratic institutions? One ostensible goal of the 2016 Russian intervention was to make Americans doubt their own political system. Although Americans espouse less approval of domestic institutions now than before 2016, it is difficult to know whether Russian intervention caused public sentiment about democracy to slide, especially since the downward trend began long before the 2016 election. How much stronger would faith in American democracy be if foreign powers refrained from interfering in U.S. elections? This question is difficult to answer with historical data, but it becomes tractable with survey experiments.

Finally, we use experiments to shed light on a third fundamental question: when would Americans allow foreign intervention to pass instead of demanding retaliation? In the aftermath of 2016, some U.S. politicians denounced Russian interference as an act of war and likened it to the attacks of September 11, 2001, which precipitated the U.S. war on terror and military intervention in Afghanistan. Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) explained, “when you use cyber … to compromise our democratic, free election system, that’s an attack against America. It’s an act of war.”Footnote 4 Others countered that Russian behavior was neither “an initiation of armed conflict” nor “a violation of the U.N Charter” and would not justify a military response.Footnote 5 How does the revelation of election interference affect public support for diplomatic, economic, and military retaliation against the aggressor, and to what extent might retaliatory sentiments split along partisan lines?

To answer these questions, we embedded experiments in a large-scale survey of the American public. All respondents read a vignette about a future U.S. presidential election. In some vignettes, a foreign government verbally endorsed one of the candidates, threatened consequences if its preferred candidate did not win, or supported a candidate by providing funding, manipulating information, or hacking into voting machines. In other vignettes, the foreign country stayed out of the election entirely.

In addition to randomizing the existence and nature of the electoral intervention, we randomized which candidate—Democratic or Republican—the foreign country favored. Finally, we randomized information about the identity of the foreign country and confidence in that assessment. Having presented the vignettes, we measured three sets of dependent variables: condemnation of the intervention, faith in American democracy, and support for retaliation.

Our experiments revealed that news of foreign intervention polarizes the public along partisan lines. Instead of rejecting foreign involvement tout court, Americans exhibited a partisan double standard. Both Democrats and Republicans were more likely to condemn foreign involvement, lose faith in democracy, and call for retaliation when a foreign power sided with the opposition, than when a foreign power aided their own party.

Our experiments also revealed that even modest forms of electoral intervention can divide and demoralize the country. Although operations such as funding, defamation, and hacking were most corrosive, mere endorsements by foreign countries also provoked substantial public ire, undermined faith in democratic institutions, and split the nation along partisan lines. At the same time, Americans—including the victims of electoral intervention—were unwilling to retaliate harshly. These findings suggest that electoral interference can be a destructive offensive tool, sowing public discord and eroding faith in democracy without provoking the level of public demand for retaliation typically triggered by conventional military attacks.

HOW DOES FOREIGN ELECTORAL INTERVENTION AFFECT PUBLIC ATTITUDES?

In recent decades, it has become increasingly common for countries to involve themselves in foreign elections. Often, this involvement aims to enhance democracy without favoring a particular candidate or party. Before elections, foreign governments and NGOs assist with electoral reforms, and during elections, they monitor activities to detect and deter irregularities.Footnote 6 Given the growth of foreign election assistance, an expanding literature investigates how external observers affect domestic perceptions of the quality of elections (e.g., Brancati Reference Brancati2014; Bush and Prather Reference Bush and Prather2017, Reference Bush and Prather2018, Reference Bush and Prather2019; Robertson Reference Robertson2015).

In some cases, however, countries seek to tip the scales; they use rhetoric and/or resources to give specific parties or candidates an electoral advantage (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2017, Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019; Bush and Prather Reference Bush and Prather2020; Corstange and Marinov Reference Corstange and Marinov2012; Levin Reference Levin2016, Reference Levin2019b; Martin and Shapiro Reference Martin and Shapiro2019). We refer to these types of activities as foreign electoral interventions.Footnote 7 The Russian interference of 2016, which aimed to help Donald Trump defeat Hillary Clinton, exemplifies this form of intervention.

Past Research about Foreign Electoral Interventions

Researchers have recently begun to investigate the effects of foreign electoral intervention. In a pioneering study, Levin (Reference Levin2016) examined how interventions by great powers affected election outcomes in target states. He found that partisan electoral interventions by the United States and the USSR/Russia during the years 1946–2000 increased the vote share of the favored candidate by three percentage points, on average. Levin also showed that partisan electoral interventions contributed to political instability by encouraging the formation of domestic terrorist groups, increasing the risk of terrorist incidents, and raising the probability of a democratic breakdown (Levin Reference Levin2018, Reference Levin2019a).

We know less about how citizens would judge the act of foreign intervention itself. If citizens became aware of foreign involvement, when would they tolerate and when would they condemn efforts to influence their own elections? Only two studies, to our knowledge, have examined this important question. Both studies made significant strides, but as we explain below, they reached conflicting conclusions. Moreover, by focusing on specific episodes in Ukraine and Lebanon, the studies left open how citizens in mature democracies would react to foreign electoral intervention, how different modes of intervention would influence public reactions, and whether foreign interference would erode confidence in democracy and provoke retaliatory foreign policies.

In one groundbreaking study, Shulman and Bloom (Reference Shulman and Bloom2012) analyzed public approval of Russian and Western involvement in the 2004 Ukrainian presidential elections. During that election, Russia offered “nakedly partisan” support for incumbent Viktor Yanukovych (455). The Russian government contributed money to Yanukovych’s campaign, and Russian President Vladimir Putin backed him publicly throughout the election. Western efforts were not as openly one-sided. The United States, the EU, and Western organizations took care not to campaign for Yanukovych’s rival, Viktor Yuschenko, and they did not contribute money to his campaign. Western countries did, however, disproportionately fund opposition parties, and Western election monitoring and exit polling contributed to Yanukovych’s defeat by exposing electoral fraud.

To study how Ukrainians reacted to Russian and Western involvement, Shulman and Bloom analyzed public opinion surveys fielded approximately a year after the election. They found that the public disapproved of both Western and Russian activities, and concluded that “foreign influence over any aspect of a state’s political development, especially one that so closely symbolises self-rule such as elections, risks unleashing a backlash fueled by citizens jealously guarding their national autonomy and national identity” (470).Footnote 8

A second study, which focused on the 2009 parliamentary elections in Lebanon, reached a different conclusion (Corstange and Marinov Reference Corstange and Marinov2012). Corstange and Marinov innovated methodologically by running a survey experiment that randomly conveyed information about American or Iranian support for one side in the Lebanese election. They then measured the public’s desire to protect foreign relations with the United States and Iran, as well as satisfaction with the role the foreign country played.

Corstange and Marinov found that foreign intervention “did not provoke a nationalistic backlash against any meddling in domestic affairs” (667). Indeed, unlike Ukrainian voters who generally rejected foreign interference, Lebanese voters sometimes appeared to appreciate foreign intervention on behalf of their preferred candidate. When Lebanese citizens heard that the United States had favored one side, those who agreed with the American position increased their desire for cooperation with the United States, whereas those who disagreed with the American position downgraded the importance of U.S. relations. News of Iranian interference did not provoke a similar split reaction, however, raising questions about why some interventions would divide the public, whereas others would not.Footnote 9

Those two studies not only reached different conclusions but also left several fascinating questions unanswered. For instance, how would voters in a longstanding democracy such as the United States judge foreign electoral intervention? As Corstange and Marinov (Reference Corstange and Marinov2012, 659) argue, voters in “fragile and unconsolidated” democracies may tolerate interventions that help their side. When the future of democracy is in doubt, it could be rational to prioritize short-term political gains over the potential negative effects of foreign meddling. Consequently, voters in unstable democracies may react more positively on average, and in a more polarized way, than voters in longstanding democracies such as the United States.

Previous research also left unclear how voters would respond to different types of electoral interventions. Corstange and Marinov (Reference Corstange and Marinov2012) reminded respondents that the United States or Iran “made it clear that it strongly preferred one side over the other,” without specifying whether the intervention went beyond verbal endorsements. Shulman and Bloom (Reference Shulman and Bloom2012), in contrast, studied historical interference that included both endorsements and other measures, making it difficult to determine which actions provoked the most public ire. By experimentally randomizing what the foreign country did, one could compare reactions to various forms of interference.

Finally, previous studies did not reveal how foreign interference affected faith in democracy or support for reprisals. We develop hypotheses about these themes, thereby setting the stage for our survey experiments. In developing our predictions, we adapt previous work to the American context and extend it to cover a broader range of potential foreign intrusions.

Hypotheses about Tolerance versus Condemnation

We hypothesize that American tolerance of foreign intervention should depend on the type of intervention and the intended beneficiary. We distinguish three modes of interference: verbal endorsements, threats, and operations. Endorsements occur when foreign countries express their opinions about candidates. Threats combine an endorsement with a promise of future reward or threat of future punishment, such as threatening to downgrade future relations if the preferred candidate loses. Finally, we use the term operations when foreign powers undertake efforts such as spreading embarrassing information about a candidate, hacking into voting systems, or donating money to an election campaign.Footnote 10

One might suppose that Americans would disapprove equally whether a foreign country states its opinion about a candidate, issues a threat, or engages in operations. After all, each of these activities has the potential to influence the election and could be seen as inappropriate foreign involvement in U.S. domestic affairs.Footnote 11 We suggest, however, that operations should provoke more American disapproval than threats, and that threats should provoke more ire than endorsements.

First, operations such as information campaigns and hacking could be perceived as greater challenges to democracy. Polls show that Americans rate democracy as the best form of government and express overwhelming support for fair elections.Footnote 12 We anticipate that citizens will judge foreign intervention based on its practical consequences for the election, as well as its consistency with democratic norms. In terms of consequences, we expect citizens to object more strongly to interventions that they believe affected the outcome. Normatively speaking, citizens should recoil at behavior that seems inconsistent with democratic values, whether or not they think it shaped the outcome.Footnote 13 By this reasoning, we anticipate that many Americans would regard foreign endorsements as harmless and legitimate forms of free speech, while viewing operations as consequential and inherently antidemocratic. We expect threats to provoke an intermediate reaction.

Second, operations and threats may be regarded as greater violations of sovereignty. The norm of sovereignty—that countries should not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries—is well established in international law and a foundation of the U.N. Charter. Shulman and Bloom (Reference Shulman and Bloom2012, 470) found that the commitment to sovereignty was “alive and well” in Ukraine and helped explain why Ukrainians rejected foreign interference during the presidential elections of 2004. We anticipate that perceptions of consequences and norms will influence public judgments about whether the intervention violated U.S. sovereignty. We predict that citizens will be most concerned about operations such as hacking into voting systems or donating money, as these directly advantage the favored candidate and involve behavior the U.N. has classified as impermissible interference in the internal affairs of another nation.Footnote 14 Americans should be more tolerant of threats and most tolerant of endorsements, which could be seen as legitimate and harmless expressions of opinion that do not intrude on American sovereignty.

We also hypothesize that revelations of foreign intervention will generate polarized partisan responses. One might expect Americans to disapprove any time a foreign country becomes involved in a U.S. election, just as they recoil against conventional military attacks on U.S. troops, territory, or equipment. However, unlike traditional forms of foreign intervention, partisan electoral interventions create domestic winners and losers: they help one candidate or party at the expense of others.Footnote 15 Given the possibility of asymmetric partisan gain, we anticipate that American voters will disapprove more strongly of foreign meddling on behalf of political opponents, than of foreign meddling to assist their own party.Footnote 16

At least three mechanisms could contribute to this double standard. The first is consequentialist. In addition to valuing democracy and sovereignty, voters care about policy outcomes. Many voters believe that victory by their own party would produce better policies than victory by the opposition. Voters should therefore disapprove more strongly of interference on behalf of domestic political adversaries, since such interference could contribute to bad policy outcomes. Conversely, they should be more tolerant of assistance for domestic political allies, since foreign assistance could help domestic allies win and contribute to more desirable policies.

The second mechanism is perceptual. We argued that when voters judge whether an intervention undermines democracy and sovereignty, they consider how consequential the intervention was for the outcome of the election. Such perceptions are, however, prone to partisan bias. Psychological studies have shown that people overestimate the extent to which others share their opinions (Ross, Greene, and House Reference Ross, Greene and House1977). This “false consensus effect” is evident in many spheres, including politics, where members of a political party overestimate public support for their own side (Delavande and Manski Reference Delavande and Manski2012). Studies also show that citizens interpret data selectively, accepting news that portrays their party in a positive light while dismissing news that portrays their party in a negative light (Bush and Prather Reference Bush and Prather2017).Footnote 17 These types of cognitive biases could cause citizens to perceive foreign intervention on behalf of their own party as less consequential—and therefore less objectionable—than foreign intervention on behalf of the opposition.Footnote 18

The final mechanism is symbolic. In sports, people disapprove when fans cheer for the opposition, even when cheerleading does not affect the outcome of a match.Footnote 19 A similar logic applies to politics: expressing enthusiasm for one’s own party seems less objectionable than expressing support for the opposition, even when expressions of support would not undermine democracy or sovereignty or alter the outcome of an election. As such, even when foreign meddling has no real impact, we predict that citizens will disapprove more strongly of meddlers who took the wrong side than of meddlers who supported the right political team.

In summary, we suggest three reasons why citizens might exhibit a partisan double standard. Foreign intervention on behalf of the opposition could be seen as contributing to bad policy outcomes, be perceived as more likely to influence the outcome of the election, and/or be castigated as symbolic support for the wrong team. Of course, not all voters have firm partisan affiliations. We anticipate that independent voters will not discriminate based on which party the intervention aimed to help.

Hypotheses about Faith in Democracy

In addition to provoking disapproval, the discovery of foreign involvement in elections could change attitudes about democracy. Previous studies have found that meddling by domestic actors raises doubts about the integrity of elections, triggering a chain reaction that delegitimizes the political system, depresses voter turnout, and encourages mass protest (Norris Reference Norris2014; Tucker Reference Tucker2007; Wellman, Hyde, and Hall Reference Wellman, Hyde and Hall2018). Research has documented the prevalence and consequences of domestic threats to electoral integrity, including efforts to block opposition parties, censor the media, launder campaign funds, gerrymander districts, suppress turnout, buy votes, stuff ballots, and manipulate the rules that translate votes into seats (e.g., Ahlquist et al. Reference Ahlquist, Ichino, Wittenberg and Ziblatt2018; Birch Reference Birch2011; Simpser Reference Simpser2013).

We extend this line of inquiry to the international realm by assessing how foreign interference affects attitudes about democracy.Footnote 20 One might think that Americans would view foreign interference as a minor annoyance that would not shake their confidence in American democracy. We expect, however, that news of foreign interference will harm faith in U.S. elections and institutions. Interventions could raise suspicions about whether electoral outcomes reflect the will of the American people. Learning of foreign intervention could also sap faith in democratic institutions and depress future political participation (Norris Reference Norris2014), although we anticipate a bigger impact on proximate outcomes (such as distrusting the results of the immediate election) than on distant and diffuse ones (such as losing faith in democracy or abstaining from future elections).

We further predict that some types of intervention will inflict more damage than others. Although democracy is a contested concept, most would regard free and fair elections as the sine qua non of a democratic system (Dahl Reference Dahl1971). Foreign behavior that biases the outcome of an election should, therefore, heighten public concerns about the health of American democracy. Operations such as hacking, funding, and disinformation seem most likely to raise suspicions of bias, whereas endorsements seem least likely to cause bias, with threats somewhere in between. We therefore predict that operations will sow distrust and undermine public confidence in political institutions to a greater degree than threats, and that threats will inflict more damage than endorsements.

Finally, we hypothesize that foreign interference will have especially corrosive effects on the democratic confidence of citizens whose party was attacked. As explained earlier, motivated reasoning should lead citizens to perceive attacks on their own party as more consequential—and therefore more threatening to democracy—than attacks on the opposition. Moreover, research has shown that citizens on the losing side of an election exhibit less faith in democratic institutions than citizens on the winning side (e.g., Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson and Guillory Reference Anderson and Guillory1997).Footnote 21 Following this logic, foreign intervention should be especially demoralizing when it appears to help the opposition win.

To what extent would such reactions weaken American democracy? Luckily, researchers expect longstanding democracies to be resilient in the face of sporadic election irregularities (Norris Reference Norris2014). One or two instances of foreign meddling would, therefore, be unlikely to trigger a collapse of America’s seasoned democratic institutions. In recent years, however, Americans have expressed high levels of dissatisfaction with U.S. elections, citing problems with gerrymandering, voting rights, and unrestricted campaign contributions.Footnote 22 In that context, Americans might see foreign intervention as part of a systemic problem, rather than an isolated setback. Whether or not American faith in democracy reaches a crisis point, any downward trend would be worrisome because when citizens distrust political institutions, leaders find it more difficult to govern effectively (Levi Reference Levi, Braithwaite and Levi1998) and to rally public support for government activity (Chanley, Rudolph, and Rahn Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000; Hetherington Reference Hetherington2004). In addition, declining turnout is concerning from the standpoint of democratic representation, particularly when turnout falls unevenly across the political spectrum. Thus, dwindling faith in U.S. democracy could have important political and normative implications.

Foreign Electoral Intervention and Foreign Policy Preferences

Finally, foreign electoral intervention could spur demands for retaliation. We consider two broad categories of options. The United States could take nonmilitary measures such as severing diplomatic relations with the offending country or imposing economic sanctions, or military measures such as threatening to use force or even launching a military strike against the meddling nation.

Which measures would citizens support, and under what conditions? We expect lower public support for military options than for nonmilitary ones. This prediction may reflect not only prudential concerns about the human and economic costs of military engagement but also normative skepticism about whether violence would constitute an appropriate response to nonkinetic attacks (Kreps and Das Reference Kreps and Das2017; Kreps and Schneider Reference Kreps and Schneider2019). Although some American politicians characterized the Russian interference of 2016 as an “act of war,” election interference presumably does not qualify as an “armed attack” that would justify military retaliation under just war theory or international law.Footnote 23 To the extent that citizens share this view, they should prefer nonmilitary options over military ones.

However, support for retaliation of any kind should depend on the mode and partisanship of the foreign intervention. Previously, we explained why citizens would be most upset about operations and least upset about endorsements. We further argued that Americans would object more strongly to interventions designed to harm their own party. Carrying these arguments to their logical conclusion, citizens should be most inclined to retaliate against operations, followed by threats and verbal endorsements. They should also be more willing to punish attacks against their own party than attacks on the opposition.Footnote 24

Moreover, the desire for retaliation should increase with certainty about the identity of the perpetrator (Kreps and Das Reference Kreps and Das2017). In some cases, intelligence agencies may have a hard time inferring who was meddling, especially if the foreign power used covert tactics to launder campaign contributions, spread disinformation, or hack into voting systems. In other cases, it might be obvious which country carried out the electoral intervention. We expect that citizens will be more willing to retaliate if they are certain they are punishing the real offender, rather than a likely but unproven suspect.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To test these hypotheses, we administered a survey experiment to a diverse sample of 3,510 U.S. adults in March–April 2018. The sample was recruited by Lucid, which selected participants to resemble the gender, age, geographic, and racial distribution of the U.S. adult population.

We began by telling participants: “On the next few pages, we will describe a situation that could take place in the future. Please read the description carefully. After you have read about the situation, we will ask for your opinions.” All respondents then received a vignette about the U.S. Presidential election of 2024.

We randomly assigned each participant to one of four groups, which varied in the degree to which a named foreign country interfered with the election. Members of the endorsement group received a scenario in which the country publicly announced its preference for one of the candidates. Members of the threat group received a vignette in which the country not only announced its preference but also intimated that a disappointing outcome would prompt it to rethink its relationship with the U.S. Members of the operation group read a story in which agents from the foreign country used money, information, or hacking in an attempt to give their favored candidate an electoral advantage. Finally, members of the stay out group received a vignette in which the foreign country did not meddle in the U.S. election.Footnote 25

We now describe each treatment in more detail. Members of the endorsement group read the following vignette, with randomized components in italics:

In 2024, the government of [country] made several public statements during the U.S. Presidential election campaign. [Country] said that it strongly preferred [candidate] and hoped [candidate] would win the U.S. Presidential election. In the end, [candidate] won the U.S. Presidential election. Observers began debating whether [country]’s statements during the campaign might have affected the results of the election.

Country was assigned to be China, Pakistan, or TurkeyFootnote 26 and candidate was either “the Democratic candidate” or “the Republican candidate.”Footnote 27 In our survey, country and candidate were randomized independently, resulting in 3 × 2 = 6 variations.

Members of the threat group received the following vignette, which not only included an endorsement but also implied that victory by the opponent might have consequences for economic and military relations with the United States:

In 2024, the government of [country] made several public statements during the U.S. Presidential election campaign. [Country] said that it strongly preferred [candidate] and hoped [candidate] would win the U.S. Presidential election. [Country] said that, if [opponent] won, it would rethink its economic and military relationships with the U.S. In the end, [candidate] won the U.S. Presidential election. Observers began debating whether [country]’s statements during the campaign might have affected the results of the election.

We independently randomized country and candidate (leaving the other politician as the opponent), yielding 3 × 2 = 6 variations.

The operation scenario involved either giving money to support a campaign, spreading true or false information, or hacking into voting machines. Subjects read the following text:

In 2024, a foreign country developed a plan to influence the U.S. Presidential election. There was a [percent] chance that the foreign country was [country]. The plan was designed to help [candidate] and hurt [opponent]. According to the plan, agents from the foreign country would [type of operation]. The foreign country carried out its plan to help [candidate] and hurt [opponent]. In the end, [candidate] won the U.S. Presidential election. Authorities began investigating whether the foreign country might have affected the results of the election.

Country and candidate (and, by implication, opponent) were randomized as described earlier. Recognizing that citizens might not be sure which foreign country carried out the intervention, we randomized percent to be 50%, 75%, 95%, or 100%. Finally, we randomized the type of operation. The foreign country’s agents would give money (“give $50 million to support the campaign of [candidate]”), spread truth (“use social media to spread embarrassing but true information about [opponent]—accurately revealing that [opponent] had broken laws and acted immorally”), spread lies (“use social media to spread embarrassing lies about [opponent]—falsely claiming that [opponent] had broken laws and acted immorally”), or hack machines (“hack into voting machines and change the official vote count to give [candidate] extra votes”). Overall, the operation scenario included 3 × 2 = 6 combinations of country and candidate, crossed with 4 × 4 = 16 combinations of percent and type of operation. Below, we simplify the exposition and increase statistical power by analyzing some of these variations while averaging over the others.

Finally, in the stay out story, the named country never carried out an intervention. The text appears below, with randomized components in italics:

In 2024, there was a false rumor that [country] had developed a plan to influence the U.S. Presidential election. In fact, [country] never had such a plan. The election proceeded without any involvement by [country], and [candidate] won the U.S. Presidential election.

As in the other scenarios, country was China, Pakistan, or Turkey, and candidate was either the Democratic candidate or the Republican candidate. Thus, the stay out group involved 3 × 2 = 6 variations. Table 1 summarizes all experimental treatments.Footnote 28

TABLE 1. Experimental Treatments

After assigning each participant to one group and presenting them with one scenario, we measured opinions about three topics.Footnote 29 First, would they approve or disapprove of how the foreign country behaved? Second, how would such events affect their confidence in U.S. elections and American democracy more generally? Finally, what foreign policies would they support with respect to the country in the scenario? We organize the remainder of the paper around these three questions.

FINDINGS

Public Disapproval of Foreign Electoral Intervention

We first investigate when the public would condemn or condone foreign electoral intervention. We predicted that Americans would object most to operations and least to endorsements, and would express greater disapproval of foreign efforts to help political opponents than of foreign assistance to their own party.

To evaluate these predictions, we asked voters whether they approved or disapproved of how the foreign country behaved. There were five response options: approve strongly, approve somewhat, neither approve nor disapprove, disapprove somewhat, and disapprove strongly. For simplicity, we focus on a natural and easily interpretable quantity of interest, the percentage of respondents who disapproved, but the online appendix documents that our conclusions hold when we analyze the full five-point scale, as well.

Figure 1 shows the average rate of disapproval in each of our intervention treatment groups: endorsement, threat, and operations. The estimates in Figure 1 integrate over the other experimental conditions in Table 1, and therefore reflect average levels of disapproval regardless of the foreign country we mentioned, the level of certainty about the perpetrator, and the party of the candidate who was favored.Footnote 30 In this figure, the dots represent point estimates, and the horizontal lines are 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 1. Disapproval of Foreign Electoral Intervention

Note: The figure shows the percentage of respondents who disapproved. Sample sizes were 1,202 for endorsement, 996 for threat, and 751 for operations. Sample sizes for the four types of operations (spread truth, spread lies, give money, and hack machines) were 181, 209, 180, and 181, respectively.

When the foreign country endorsed a candidate, 37% of our subjects disapproved, even though the foreign country did no more than express its preferences. As predicted, disapproval was higher (55%) when the foreign country not only expressed a preference but also threatened to downgrade relations with the United States if its favorite candidate lost. These findings were not preordained. One might think that foreign countries, like domestic political actors, would be entitled to voice their opinions and engage with some partners more than others. However, many who read the endorsement scenario and most who read the threat scenario reacted with disdain.

As expected, disapproval was highest (77%) when the country implemented operations to bolster its favored candidate. The bottom portion of Figure 1 disaggregates the four types of operations in our experiment. Approximately 72% of respondents disapproved when the foreign country spread embarrassing but true information about a candidate. Reactions were even more negative when the foreign country spread lies, gave money for campaigning, or hacked into voting machines. In those situations, disapproval hovered between 78% and 79%.Footnote 31

The bottom portion of Figure 1 also suggests some surprising conclusions. Citizens apparently did not draw a sharp distinction between spreading truth and spreading lies. In the “spreading truth” scenario, agents from the foreign country used social media to spread embarrassing but true information about one of the candidates, accurately revealing that the candidate had broken laws and acted immorally. One might think that some Americans would welcome, or at least tolerate, information about actual improprieties by a U.S. presidential candidate. Instead, 72% of respondents disapproved when the foreign country disseminated true information. A higher proportion, 79%, disapproved of spreading lies, but the difference in reactions to these two treatments was only 7 percentage points.

Moreover, respondents reacted just as negatively to foreign campaign contributions as to spreading lies or hacking election machines. One might expect citizens to view campaign contributions as more legitimate than falsely scandalizing a candidate or rigging the electoral tally. On the contrary, Americans in our study viewed foreign money as no less objectionable than disinformation and cheating.

We also investigated how partisanship moderated reactions to foreign interference.In our sample, 36% of respondents were Democrats, 29% were Republicans, and the remainder were Independents who did not identify with either party. For each of these sets of respondents, we measured the percentage who disapproved of each mode of intervention, while holding the winner of the election constant.

Figure 2 summarizes how Republicans, Independents, and Democrats reacted to each type of foreign intervention. Consider how Republicans responded to foreign endorsements, shown in the top left corner of the figure. In our experiment, 50% of Republicans disapproved when the foreign country endorsed the Democrat (Country Favored D), whereas only 22% of Republicans disapproved when the foreign country endorsed the Republican (Country Favored R). This example fits our hypothesis that Americans react more negatively to foreign intervention on behalf of the opposition, than to otherwise equivalent intervention in support of their own party.

FIGURE 2. Disapproval of Foreign Electoral Intervention, by Partisanship

Note: The figure gives a partisan breakdown of the percentage of respondents who disapproved of the foreign country’s behavior. For each type of intervention, the figure shows how Republicans, Independents, and Democrats reacted when the foreign country favored the Republican candidate (Country Favored R), and when the foreign country favored the Democratic candidate (Country Favored D). For each of the six combinations of partisanship on the vertical axes, there were between 155 and 233 observations in the endorsement group, 144–193 observations in the threat group, and 99–148 observations in the operations group.

Reactions among Democratic voters were similarly partisan. As the lower left corner of Figure 2 shows, disapproval among Democrats was 53 percentage points when the foreign country endorsed a Republican, versus 28 percentage points when the foreign country endorsed a Democrat.Footnote 32 These examples illustrate a remarkable double standard that arose throughout our experiment. As expected, the reactions of Independent voters were far less sensitive to which party the foreign country endorsed.Footnote 33

We found similar patterns when the foreign country threatened that the outcome could affect future economic and military relations with the United States (middle column of Figure 2). Among Republicans, 71% disapproved when the country sided with the Democratic candidate, versus only 51% when the country sided with the Republican candidate. Democrats also responded in a partisan fashion; their disapproval was 71% when the foreign country backed the Republican, compared with 39% when the foreign country backed the Democrat. As expected, the effect of threats on Independent voters did not depend on which side the foreign country took.

The right side of Figure 2 shows the results when the foreign country undertook operations. Here, we found stronger bipartisan pushback: strong majorities of respondents disapproved of operations, including operations designed to help their own party. Nonetheless, partisan double standards persisted. Among Republicans, disapproval was 87% when foreign operations aimed to help the Democrat, compared with 67% when foreign operations aimed to help the Republican. Likewise, Democrats reacted more negatively (87%) when the foreign country sided with the Republican than when the foreign country sided with the Democrat (72%). Once again, the reactions of Independents were less sensitive to which side the foreign country took.Footnote 34

Figure 2 also shows how foreign electoral interference could split the American electorate. For example, when the foreign country issued threats on behalf of a Democratic candidate, most Republicans (71%) disapproved, but only a minority of Democrats (39%) objected. Likewise, when a foreign country privileged the Republican in this way, the vast majority of Democrats (71%) protested, but only half (51%) of Republicans balked. These results illustrate how foreign interference sows domestic divisions.

It is worth considering how our experimental design might have affected the magnitude of the partisan differences we uncovered. Our scenarios conveyed no ambiguity about whether the foreign country tampered with the U.S. election. On the one hand, the endorsements and threats we studied are by nature public, affording little opportunity for observers to disagree about what the foreign country said (Levin Reference Levin2016, 193). On the other hand, countries typically try to keep operations secret, creating uncertainty—at least initially—about what the foreign country did.Footnote 35 For example, after the 2016 U.S. election, some Republican elites, including President Donald Trump, dismissed Russian operations as a hoax that Democrats had fabricated to rationalize why their candidate lost. If we conducted experiments in which elites debated or questioned whether operations occurred, would we find even sharper partisan differences? We leave this as a topic for future research.

One might also ask whether the events of 2016 might have affected average disapproval in our scenarios. On the one hand, mainstream news media tended to portray Russia’s behavior in a negative light, potentially amplifying the disapproval we observed in our 2018 experiments. On the other hand, Russia’s interference in 2016 spurred Americans to develop reasoned opinions about foreign involvement in U.S. elections, potentially increasing the external validity of our experiments. Future research could evaluate these conjectures.

Finally, did Russian interference in 2016 affect our findings about partisanship? After 2016, Democrats and Republicans were exposed to different portrayals of Russian behavior. Democratic leaders and much of the news media tended to depict Russian interference as an unacceptable and consequential attack on the United States. By contrast, Republican opinion leaders often portrayed Russian meddling as fabricated or inconsequential. Our study suggests that, despite the markedly different messages Democrats and Republicans may have internalized about 2016, voters from both parties apply similarly biased standards when judging hypothetical future interventions. Future research could evaluate whether these partisan portrayals influenced reactions to our scenarios in subtle ways and, more generally, whether past experiences of intervention shape future reactions.

Foreign Electoral Intervention and Attitudes about Democracy

We next consider how foreign electoral intervention affected attitudes about democracy. We hypothesized that intervention would undermine trust in the election results, erode faith in democratic institutions, and depress future political participation. We further expected that operations would inflict more damage than threats, threats would cause more damage than endorsements, and voters would react more negatively if the foreign country sided with the opposition.

To gauge attitudes about American democracy, we asked respondents in each of the four treatment groups (stay out, endorsement, threat, and operations): “If the 2024 election happened just as we described, would you agree or disagree with the following statements?” The three statements were, “I would trust the results of the election,” “I would be unlikely to vote in future elections,” and “I would lose faith in American democracy.” We calculated the percentage of respondents who agreed or disagreed with each statement.

We found that foreign intervention greatly increased distrust in the results of the election (first graph in Figure 3). When the foreign country stayed out, 25% voiced distrust, reflecting preexisting cynicism about the integrity of American elections. But distrust increased to 38% when the foreign country offered an endorsement, 42% when the country coupled the endorsement with a threat, and 71% when the country carried out operations.Footnote 36

FIGURE 3. Attitudes about Democracy, by Mode of Foreign Electoral Intervention

Note: The figure shows, by treatment condition, the percentage of respondents who said they would distrust the results of the election (top panel), lose faith in American democracy (middle panel), or avoid voting in the future (bottom panel). Sample sizes were 561 for stay out, 1,202 for endorsement, 996 for threat, and 751 for operations, comprised of 181, 209, 180, and 181 for spread truth, spread lies, give money, and hack machines, respectively.

Foreign intervention not only sowed doubts about the current election but also eroded faith in U.S. democracy (second graph in Figure 3). Although 23% lost faith even when the foreign country refrained from intervening, that figure increased to 29% when the foreign country endorsed one of the candidates, 36% when the endorsement came with a threat, and 49% when the country undertook concrete operations.

Finally, foreign intervention modestly depressed future intentions to vote (third graph in Figure 3). When the foreign power stayed out of the election, 20% of subjects said they would abstain from voting in future elections. Avoidance of voting rose to 21% when the foreign country merely expressed its opinion, 24% when the country put future relations on the line, and 29% when the foreign country carried out operations.

Overall, these findings suggest that foreign involvement could have profoundly negative effects on American democracy. Interference in a presidential election would increase distrust in the immediate results, while also affecting—to a lesser degree—more distant outcomes such as faith in American democracy and participation in future elections. Moreover, our experiments indicate that foreign countries can adversely affect the American psyche through words alone. By verbally endorsing a Presidential candidate, with or without threats, foreign powers have the potential to undermine confidence in the American political system.

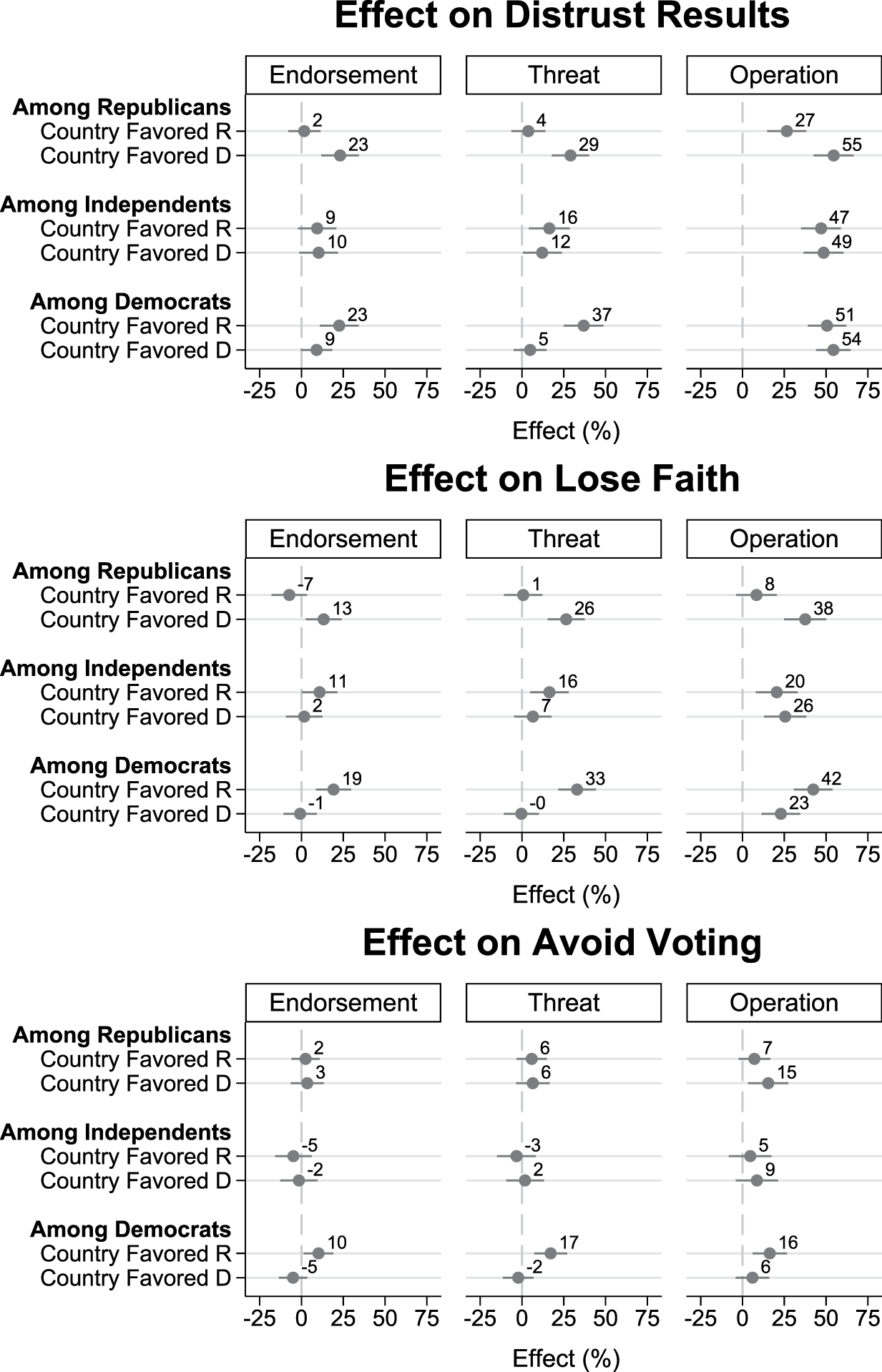

We hypothesized that intervention would not only be corrosive on average but also prompt different reactions depending on partisanship. Figure 4 shows the effect of intervention on attitudes about democracy among Republicans, Independents, and Democrats. We calculated intention-to-treat effects by taking attitudes about democracy in each treatment condition and subtracting attitudes in the baseline condition, when the country stayed out but the same candidate won.Footnote 37 The black dots are average intention-to-treat effects, and the thin lines are 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 4. Effects of Foreign Electoral Intervention on Attitudes about Democracy, By Partisanship

Note: The figure gives a partisan breakdown of intention-to-treat effects of foreign electoral intervention on the percentage of respondents who said they would distrust the results of the election (top panel), lose faith in American democracy (middle panel), or avoid voting in the future (bottom panel). In all cases, the effect is the change caused by intervening instead of staying out. For each of the six combinations of partisanship on the vertical axes, there were between 83–109 observations in the stay out (control) condition. Sample sizes for the intervention conditions were as in Figure 2.

Figure 4 shows evidence of a partisan double standard. Consider, for example, Democrats’ reactions to foreign endorsements, shown on the left-hand side of each of the three panels. When the foreign country endorsed the Republican (Country Favored R), Democrats became substantially more likely to distrust the results (23-point effect), lose faith in democracy (19-point effect), and avoid voting in the future (10-point effect). But when the foreign country endorsed the Democrat (Country Favored D), Democrats were typically indifferent, exhibiting no statistically significant changes in attitudes about democracy.

Republicans displayed a double standard, as well. Republican distrust of the outcome and skepticism about democracy swelled to a much greater degree when the foreign country endorsed a Democrat than when the foreign country endorsed a Republican. (By contrast, endorsements did not elicit a double standard in Republican willingness to vote.) Finally, endorsements caused Independents to sour on democracy, but not to the same degree as citizens who witnessed interference against their own party. Foreign threats produced similar patterns, as shown in the middle column of Figure 4.

The right side of Figure 4 presents intention-to-treat effects when the foreign country carried out operations. On the one hand, all estimates were positive, and most were significantly distinguishable from zero. Thus, operations undermined the democratic ethos even among citizens the intervention was designed to help. On the other hand, voters tended to be more negative about American democracy when the foreign country favored the opposing side.

In sum, revelations of even modest forms of electoral intervention undermined confidence in American democracy while also pitting Republicans and Democrats against each other. Thus, foreign interference provides foreign countries with a potent weapon for weakening the United States.

Foreign Electoral Intervention and Foreign Policy Preferences

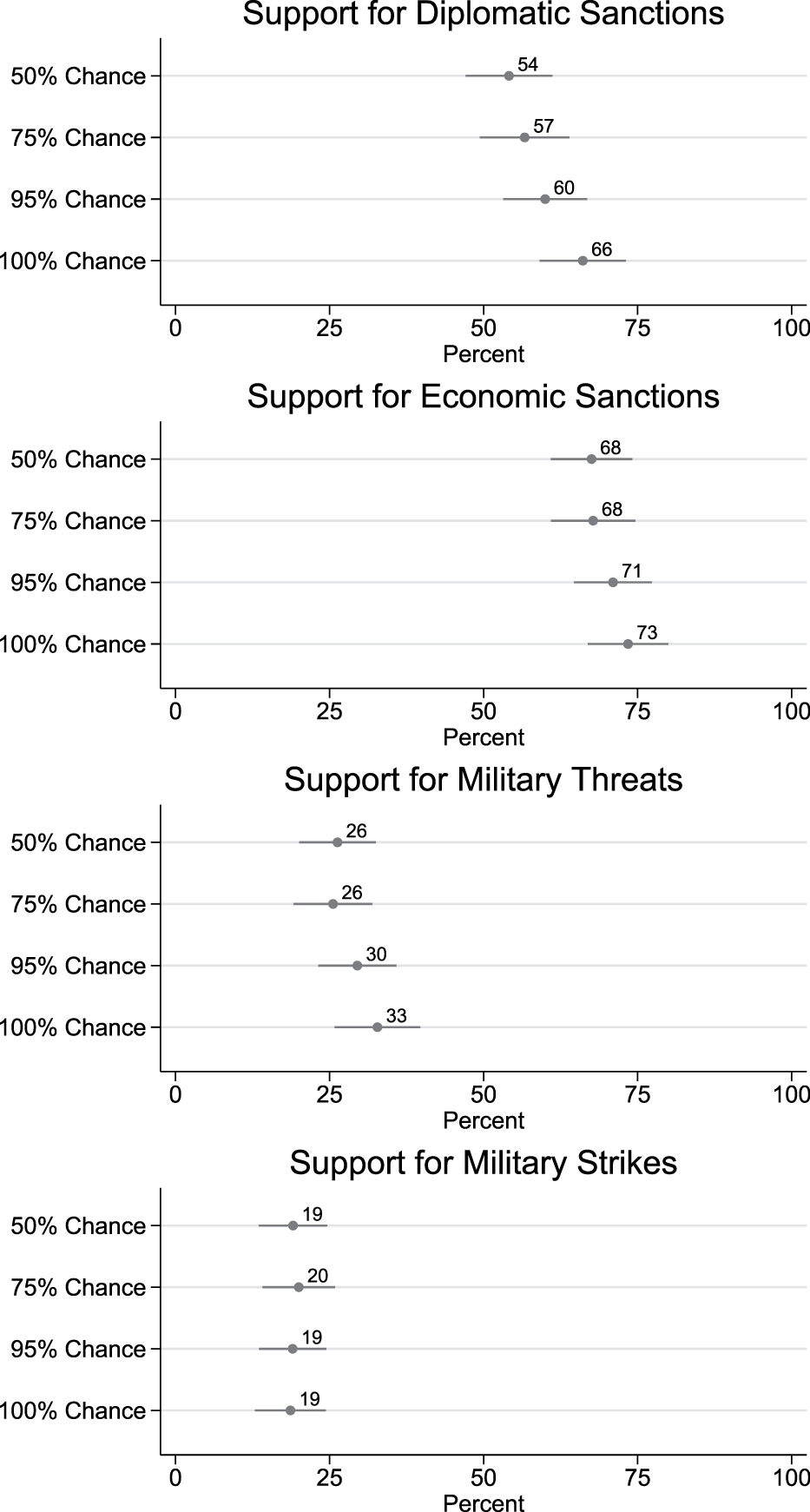

Finally, we investigated public support for retaliation against foreign interference in U.S. elections. We expected higher public support for nonmilitary options, such as diplomatic or economic sanctions, than for military responses such as threatening or initiating armed conflict. We further predicted that support for both kinds of retaliation would be strongest for operations and weakest for endorsements, and would be higher when the foreign country aided the opposing party. Finally, we expected that the desire to retaliate against operations would rise with certainty about which country was responsible.

To measure support for retaliation, we asked respondents whether they would support or oppose each of the following policies if the 2024 election happened just as we described: cutting off diplomatic relations with [country], imposing economic sanctions on [country], threatening to use military force against [country], and launching a military strike against [country]. Figure 5 shows the percentage of respondents who supported each policy option, conditional on whether and how the foreign country intervened.Footnote 38 Each dot represents the mean level of support, averaging over the other features in the experiment. (Later, we test whether these conclusions depended on certainty about the identity of the foreign country.)

FIGURE 5. Support for Foreign Policies, By Mode of Foreign Electoral Intervention

Note: Each panel in the figure shows the percentage of respondents who supported a given foreign policy, by treatment condition. Sample sizes were as in Figure 3.

The figure reveals several conclusions. First, citizens resoundingly rejected military responses to foreign electoral intervention. Even in the face of operations to fund candidates, manipulate information, or hack into voting machines, only 28% wanted to make military threats, and only 19% called for military strikes. Second, diplomatic and economic sanctions received majority support only when the foreign country conducted operations. This is surprising, given that verbal statements triggered public ire and undermined confidence in democracy. It appears that foreign countries could undertake destructive verbal interventions (with or without threats), secure in the knowledge that none of the retaliatory measures we studied would attract support from a majority of the American public. Furthermore, adversaries could carry out electoral attacks without running the risk that the public would demand military retaliation.Footnote 39

We also hypothesized that support for retaliation would depend on partisanship. Figure 6 tests this hypothesis by splitting the sample into Republicans, Independents, and Democrats. Within each group, the figure shows how each type of foreign intervention affected support for tough policies (diplomatic sanctions, economic sanctions, military threats, or military strikes), relative to baseline support for those same policies when the foreign country stayed out entirely. The dots in Figure 6 are average intention-to-treat effects, integrating over the other dimensions of the experiment.

FIGURE 6. Effects of Foreign Electoral Intervention on Support for Foreign Policies, by Partisanship

Note: Each panel of the figure gives a partisan breakdown of the effect of foreign electoral intervention on support for a given foreign policy. Sample sizes were as in Figure 4.

Once again, we found evidence of a partisan double standard. For nearly every combination of mode of intervention and method of retaliation, Republicans reacted more strongly to “Country Favored D” scenarios than to “Country Favored R” scenarios, whereas Democrats did the opposite. Although the differences were almost always in the expected direction, only a few were statistically significant at conventional levels.Footnote 40

These patterns suggest what kinds of retaliatory policies might—or might not—be politically feasible after an electoral intervention. According to Figure 6, electoral interventions may be less likely to spur retaliatory sentiment by members of the winning party than by members of the losing party. This means, for example, that if a Republican candidate rode to victory in the context of pro-Republican interference, Democrats might demand retaliation, but members of the newly elected president’s own party would be less willing to go along. Knowing this, foreign countries might feel even more confident that they could intervene with relative impunity.

Finally, we conjectured that support for hostile foreign policies would increase with the level of certainty about which country was culpable. To test this possibility, we compared support for retaliation when respondents were 50%, 75%, 95%, or 100% certain of the identity of the country that carried out operations. (Recall, from Table 1, that we did not raise doubts about the identity of the country in the endorsement and threat conditions, because such expressions are by definition overt, leaving no ambiguity about who made the statement.)

We found some evidence for this hypothesis, but less than expected. Figure 7 shows how support for each policy varied by the level of certainty, averaging over the other dimensions of our experiment. To our surprise, citizens were nearly as likely to support diplomatic and economic sanctions when they were only 50% sure about the identity of the perpetrator, as when they were completely certain that the named country had conducted the operation. Support for nonmilitary retaliation rose steadily with certainty, but the differences between 50% and 100% certainty were relatively small: 66–54 = 12 points for diplomatic sanctions, and a 73–68 = 5 points for economic sanctions. The patterns for military threats were similar, albeit with lower baseline levels of support. Finally, certainty had no appreciable effect on support for military strikes.

FIGURE 7. Support for Foreign Policies, by Certainty about the Identity of the Foreign Country

Note: Each panel of the figure shows the percentage of respondents who supported a given foreign policy, for each of the four levels of certainty about the identity of the foreign country. Sample sizes were 194 for 50% chance, 180 for 75%, 200 for 95%, and 177 for 100%.

Overall, our findings about uncertainty have a surprising political implication: although investigations into electoral intervention might increase clarity about the identity of the perpetrator, the accumulation of evidence may not result in substantially higher public support for international retaliation.

In summary, our data revealed an American reluctance to retaliate against even the most objectionable forms of foreign intervention in U.S. elections. Americans overwhelmingly rejected military responses to foreign interference, even when a foreign country undertook operations such as funding candidates, manipulating information, or hacking into U.S. voting machines, and even when the identity of the foreign attacker was known with certainty. Voters were more supportive of nonmilitary responses such as diplomatic and economic sanctions, but majorities endorsed these measures only when the foreign country had engaged in operations. Thus, countries that aspire to interfere in U.S. elections might take comfort in knowing that their actions, however detrimental to American democracy, might not provoke unified support for retaliation.

CONCLUSION

Despite the growing importance of election interference for contemporary politics (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2017, Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019; Levin Reference Levin2016, Reference Levin2019b), we know relatively little about how Americans judge foreign meddling in U.S. elections. In this article, we used survey experiments to investigate three fundamental questions about how Americans would respond to revelations of foreign electoral intervention.

First, when would U.S. citizens tolerate foreign involvement in American elections, instead of condemning external efforts to tip the scales? In our experiments, American tolerance of intervention was conditional on the intended beneficiary. Both Democrats and Republicans exhibited a clear double standard, disapproving more strongly of foreign efforts to help the opposition than of otherwise identical efforts to help a candidate from their own party.

The polarizing effects of foreign electoral intervention are, therefore, more widespread than previously appreciated. In a seminal article, Corstange and Marinov (Reference Corstange and Marinov2012) found that when foreign countries took sides in the Lebanese election of 2009, the domestic public split along partisan lines. Corstange and Marinov expected this type of reaction in “fragile and unconsolidated” democracies such as Lebanon, but speculated that such a response might not be plausible in “consolidated democracies,” where they anticipated stronger bipartisan pushback. On the one hand, consistent with this prediction, our experiments in the United States showed that bipartisan majorities disapproved of foreign operations to influence U.S. elections. On the other hand, the American public reacted in a polarized way to all three types of foreign interference we studied. Hence, the divisive effects of electoral intervention are not limited to fragile democracies; they arise in highly established democracies, as well.

Our findings about partisan polarization shed new light on past interventions, while also portending sharp political cleavages in the future. Following the 2016 election, Republicans were far more likely than Democrats to deny that Russia intervened, or to acknowledge Russian meddling but dismiss it as inconsequential. Our experiments suggest that such reactions arose not from principled differences between the parties, but instead from a pervasive tendency to apply politically biased standards when judging the behavior of other countries. Having randomized which party the foreign country favored, we found that both Democrats and Republicans were far more willing to tolerate foreign support for their own party than for the opposition. Partisan differences were smaller when the country carried out operations such as spreading lies about candidates or hacking into voting machines, but partisan bias persisted even then. Thus, if a foreign country took the Democratic side in a future election, the political reaction might be the reverse of 2016, with Republicans denouncing and Democrats condoning the foreign interference.

Our experiments further showed that public tolerance depended not only on the intended beneficiary but also on the type of intervention. Although many citizens denounced foreign endorsements, they were more likely to condemn threats, and they objected most to operations such as donating money to a campaign, disseminating embarrassing information about a candidate, or hacking into voting machines. These findings underscore the importance of distinguishing different types of electoral interventions, to see how Americans would respond to the wide variety of tools countries could employ in U.S. elections.

We also used experiments to investigate a second fundamental question: when would news of foreign electoral intervention undermine confidence in democratic institutions? In our experiments, voters who learned of foreign intervention were substantially more likely to distrust the results of the election, lose faith in American democracy, and abstain from participating in future elections. Reactions were not symmetric across the population, however. Instead, foreign interference led to partisan splits about the state of U.S. democracy. Thus, foreign involvement can have profoundly negative and divisive effects on confidence in American democracy.Footnote 41

Finally, we studied how election interference changed public attitudes about foreign relations. Regardless of the form of electoral intervention, citizens in our experiments rejected military threats and military strikes. Although many prominent observers characterized the Russian intervention of 2016 as an act of war, the electoral equivalent of 9/11, and a direct attack on institutions at the heart of American democracy, our experiments suggested that even operations such as hacking the vote tally would not spur the American public to resort to military force.

We did find majority support for diplomatic and economic sanctions, but only when the foreign government interfered thorough operations such as funding parties, manipulating information, or hacking into voting equipment. Foreign endorsements and threats, on the other hand, failed to generate majority support for any reprisals. Finally, consistent with our findings about a partisan double standard, both Democrats and Republicans were less willing to retaliate when the foreign power favored their own party than when the foreign power backed the opposition. These patterns suggest that foreign countries could interfere in American elections without triggering bipartisan public demand for tough retaliation.

Future studies could extend our approach in a several ways. One could, for example, introduce ambiguity about whether foreign countries meddled in elections. Our experiments asked how Americans would respond to clear revelations of foreign intervention. To find out, we presented the existence or absence of foreign intervention as undisputed, while allowing some uncertainty about the identity of the perpetrator. Follow-up experiments could present inconclusive evidence about whether a foreign country intervened, describe partisan disagreement about whether external intervention took place, or both. One could compare reactions in those scenarios with what we found in our experiments.Footnote 42

Future experiments could also vary other features of the intervention. We focused on partisan interventions in which the foreign country promoted one candidate at the expense of another. Foreign countries could instead intervene evenhandedly by undermining or supporting both sides in the contest. Using experiments, one could compare public tolerance for partisan versus evenhanded interventions, assess how the two types of incursions would affect confidence in democracy and willingness to retaliate, and study whether Democrats and Republicans would unite against foreign meddling that did not try to give one side an advantage. It would also be instructive to conduct experiments about multipronged interventions that not only take sides but also attempt to modify electoral procedures (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2017, Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019).

In addition, future research could explore the effects of election interference in other countries. For example, we found that Americans opposed retaliation, despite living in one of the most powerful countries in the world. Citizens in weaker countries would presumably be even less willing to retaliate, especially against global or regional superpowers. Similarly, future studies could explore whether the divisive effects of foreign electoral intervention depend on the political context. We found that foreign interference split the American public along partisan lines. How would citizens react in countries with stronger (or weaker) levels of partisan identification, or in countries where parties are programmatically more (or less) distinct than the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States? Would reactions depend on the age of the democracy or the nature of the electoral system? This article could serve as a blueprint for follow-up experiments to assess responses to election interference not only in the United States but also in other democracies.

Moreover, future research could study how the identity of the intervening country shapes public perceptions. In our experiment, the name of the country mentioned had little effect on disapproval, faith in democracy, and support for retaliation. Future research could examine how American and foreign publics would respond to interference by other countries, both friendly and unfriendly.

In the meantime, our findings suggest that foreign electoral intervention represents a significant threat to democracies such as the United States. Previous research has shown that foreign powers can use electoral intervention to boost the chances of their favored candidate or party (Levin Reference Levin2016). Our experiments add that electoral intervention can polarize the electorate and diminish faith in democratic institutions without provoking the kind of public demand for retaliation prompted by conventional military attacks.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000064.

Replication materials can be found on Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E3BAO5.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.